Abstract

Proper regulation of energy metabolism requires neurons in the central nervous system to respond dynamically to signals that reflect the body’s energy reserve, and one such signal is leptin. Agouti-related protein (AgRP) is a hypothalamic neuropeptide that is markedly upregulated in leptin deficiency, a condition that is associated with severe obesity, diabetes, and hepatic steatosis. Because deleting AgRP in mice does not alter energy balance, we sought to determine whether AgRP plays an indispensable role in regulating energy and hepatic lipid metabolism in the sensitized background of leptin deficiency. We generated male mice that are deficient for both leptin and AgRP [double-knockout (DKO)]. DKO mice and ob/ob littermates had similar body weights, food intake, energy expenditure, and plasma insulin levels, although DKO mice surprisingly developed heightened hyperglycemia with advancing age. Overall hepatic lipid content was reduced in young prediabetic DKO mice, but not in the older diabetic counterparts. Intriguingly, however, both young and older DKO mice had an altered zonal distribution of hepatic lipids with reduced periportal lipid deposition. Moreover, leptin stimulated, whereas AgRP inhibited, hepatic sympathetic activity. Ablating sympathetic nerves to the liver, which primarily innervate the portal regions, produced periportal lipid accumulation in wild-type mice. Collectively, our results highlight AgRP as a regulator of hepatic sympathetic activity and metabolic zonation.

Agouti-related protein is not a necessary downstream effector of leptin regarding feeding, energy expenditure, and body weight, but rather it mediates hepatic lipid abundance and zonal distribution.

The high prevalence of obesity has increased the burden of a number of associated metabolic conditions, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Given that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a key risk factor for the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and consequent cirrhosis, these epidemiologic trends place urgency on more precisely understanding what regulates liver fat deposition.

Leptin is released from the white adipose tissues in amounts that are proportional to the body’s fat mass, thus conveying the abundance of the body’s energy stores to the brain. Leptin not only regulates appetite and energy expenditure, it also regulates glucose and lipid homeostasis, blood pressure, bone mass, and reproduction via mechanisms independent of food intake and body weight (1, 2). Leptin is transported across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and acts on a number of distinct neuronal subgroups in hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic regions that express leptin receptors (LepRs). Among these, hypothalamic neurons expressing Agouti-related protein (AgRP) express the long form of the LepR (LepRb) and are negatively regulated by leptin (3). AgRP mRNA expression is markedly upregulated in leptin-deficient (Lepob/ob) mice, and it is suppressed by leptin treatment (4). Leptin also lowers the firing rates of AgRP neurons and attenuates their release of AgRP neuropeptide (4–6). We recently showed that AgRP neurons are unique among hypothalamic neurons, in that most of these neurons are situated outside the BBB (7, 8), and that these neurons are more sensitive to dynamic changes in circulating leptin levels (7).

Although these findings strongly suggest that AgRP neurons are key downstream effectors of leptin, deleting LepR specifically in AgRP neurons produces only transient hyperphagia and modest weight gain (9). Moreover, targeted deletion of the Agrp gene in mice does not alter food intake and body weight (10). Notably, AgRP neurons also coexpress neuropeptide Y (NPY) and the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and recent evidence has attributed most of the orexigenic effects of AgRP neurons to these factors, rather than to AgRP (11–13). Intriguingly, although deleting the Npy gene alone in mice also has no effect on feeding or body weight, NPY deficiency in the context of Lepob/ob reduces food intake, increases energy expenditure, and partially normalizes obesity and hyperglycemia otherwise seen in such mice (14). In contrast, loss of AgRP in female LepR-deficient mice rescues fertility but not body weight (15, 16). Thus, three factors produced by AgRP neurons, that is, AgRP, NPY, and GABA, may each mediate functionally segregated aspects of leptin action, however the physiological role of AgRP in particular requires further elucidation.

In addition to their roles in regulating energy balance, leptin and the central melanocortinergic neurons also regulate peripheral tissue metabolism via the autonomic nervous system independently of food intake and body weight (17–21). Specifically, leptin has been shown to act in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus to regulate the firing rates of nerves innervating the liver (22). Moreover, leptin reduces lipodystrophy-associated hepatic steatosis by stimulating hepatic α1-adrenergic receptors and AMP-activated protein kinase activity (23). Given that hepatic steatosis is a hallmark of leptin deficiency and that AgRP expression is markedly elevated in Lepob/ob mice, we investigated the potential role of AgRP in mediating leptin’s effects on hepatic lipid metabolism. We show that AgRP acts in the brain to inhibit hepatic sympathetic activity, and that the loss of AgRP in Lepob/ob mice affects total hepatic lipid content and distribution in an age-dependent manner.

Materials and Methods

Animals and diets

Lepob/+ mice were originally purchased from the The Jackson Laboratory. Agrp−/− mice (AKO) were provided by Dr. Gregory Barsh at Stanford University (Stanford, CA), and these mice were on mixed genetic background. To generate double mutant mice that lack leptin and AgRP, Lepob/+ mice were crossed with AKO to create Lepob/+, Agrp+/− breeders, which were further crossed with Lepob/+, Agrp+/− or Lepob/+, Agrp−/− to generate double mutants and littermate controls. Mice were housed in a barrier facility with a 7:00 am to 7:00 pm light/dark cycle and fed a standard mouse chow (21.6% kcal from fat; Purina mouse diet no. 5058) unless indicated otherwise. All experiments were carried out under a protocol approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Measurements of body composition and parameters of energy balance

Metabolic studies and body composition measurements in mice were performed at the University of California, San Francisco Mouse Metabolism Core. Briefly, body composition (lean and fat mass) was measured by EchoMRI. Indirect calorimetry, locomotor activity, food intake, and energy expenditure were measured using a 12-chamber comprehensive laboratory animal monitor system (CLAMS) system (Columbus Instruments). Energy expenditure was calculated using the formula energy expenditure = (3.815 + 1.232 × respiratory exchange ratio) × oxygen consumption. Data from the first day in the CLAMS chambers, when mice acclimatized, were discarded.

Insulin and triglyceride measurements

Blood was collected in heparinized capillary tubes, kept on ice, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes, and stored at −80°C. Plasma insulin was measured using an ultrasensitive mouse insulin ELISA kit (Crystal Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL; catalog no. 90080) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Liver lysates were made by homogenization of 30 to 50 mg of flash-frozen liver in ice-cold buffer [250 mM sucrose, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)]. Triglycerides from both plasma and liver lysates were measured colorimetrically using reagents and instructions from the total triglyceride determination kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; catalog no. TR0100).

Lipidomics

Liver tissues were weighed and flash frozen. Lipidomic analyses were performed as previously described in the supplemental methods of Louie et al. (24).

Partial hepatic sympathectomy with 6-hydroxydopamine

C57BL/6N mice between 7 and 10 weeks of age were divided into two weight-matched groups and the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) group was randomly assigned. 6-OHDA (100 mg/kg in 0.9% NaCl and 10−7 M ascorbic acid; Sigma-Aldrich) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl and 10−7 M ascorbic acid) was given by IP injection every other day for a total of three injections. After 3 days of recovery all mice were placed on a high-fat diet (60% kcal from fat, D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) for 3 weeks, after which mice were fasted for 6 hours before tissue harvesting.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Immunofluorescence analysis was performed similarly to what was described previously (8, 25). Briefly, liver sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes. After blocking, the slides were incubated with a polyclonal antibody for NPY (1:1000; Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA; RRID: AB_2314974) for 36 hours at 4°C, or with a rabbit monoclonal antibody for fatty acid synthase (FAS; 1:250; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA; RRID: AB_2100796) for 36 hours at 4°C. The sections were washed and incubated with the secondary antibody donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (1:200; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY; RRID: AB_141637) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1:2000) for 1 hour at room temperature. Another wash was done and the slides were then incubated with BODIPY™ 493/503 (1:5000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 40 minutes.

Analysis of hepatic lipid accumulation

Flash-frozen livers were cryosectioned at 15 µm in thickness. Oil Red O (ORO) staining was carried out according to a procedure described in Mehlem et al. (26). Bright-field images were collected at low magnification (×5) to include multiple portal triads and central veins in the same image. To avoid sampling bias, five to six images were taken to cover different regions of the same liver. In Lepob/ob mice or mice lacking both leptin and AgRP (DKO), large ORO-positive lipid droplets were predominantly and consistently found across the liver lobule but absent in regions immediately adjacent to the portal triads, and the extent of this periportal lipid sparing differed between the two genotypes. To quantify the extent of this lipid sparing surrounding the portal regions, ORO-stained sections were analyzed by ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) according to the protocol described in Mehlem et al. (26), and investigators were blinded to conceal the corresponding genotypes. Briefly, RGB images were converted to grayscale and the same intensity threshold was used to define ORO positivity for every image. The percentage area positive for ORO is the percentage of the entire image area that was stained by ORO.

To quantify hepatic lipid accumulation in wild-type mice after sympathetic nervous system (SNS) ablation, BODIPYTM 493/503 staining was coupled to NPY immunofluorescence to simultaneously visualize neutral lipids and SNS fibers, respectively, in liver lobules. We focused our analysis on the periportal regions because hepatic NPY-positive SNS fibers are exclusively found around the portal triads in mice, and because portal triads can be identified anatomically, allowing us to categorize a given portal triad as either “intact” or “ablated.” The region of interest was defined as the area of hepatic parenchyma encircled by a radius of four hepatocytes away from a given portal vein to ensure that the region of interest always fell within zone 1 of any liver lobule (27). BODIPY-positive area within the region of interest was measured as for ORO. Because unequal numbers of intact and ablated portal triads were observed in different mice, least square means were computed and used to compare ablated (NPY-negative) regions with intact (NPY-positive) regions of the same mice using two-way ANOVA.

Intracerebroventricular injection

Stereotaxic surgery was performed to place 2.5-mm-long cannulas into the later ventricle at +1 mm lateral, −0.3 mm anterior–posterior, −2.7 mm ventral–dorsal. Placement of cannulas was tested by injection of 0.2 µg of angiotensin II to induce water drinking. All mice were allowed to recover for a minimum of 2 weeks before experiments began. To administer AgRP, mouse AgRP82–131 (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Burlingame, CA) or artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) at a volume of 2 μL was infused into the lateral ventricle of the brain through a guide cannula. The amount of AgRP injected is described in the figure legend of each experiment.

Norepinephrine turnover assay

Nine-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the The Jackson Laboratory (JAX). These mice were divided into three groups of equal body weights, designated as baseline, PBS (vehicle), or leptin. On the morning of day 1, mice in all three groups were fasted for a total of 24 hours to lower endogenous leptin levels. The next morning (day 2), mice in the baseline group were euthanized and their livers were flash frozen. Mice in the vehicle and leptin groups were given an IP injection of α-methyl-p-tyrosine (α-MPT; 250 mg/kg) to block biosynthesis of norepinephrine. One hour later, mice in the vehicle group were given an IP injection of PBS, and mice in the leptin group were given an IP injection of leptin (5 mg/kg; National Hormone and Peptide Program). Two to 2.5 hours later (about 3 to 3.5 hours from the first α-MPT injection), a second dose of α-MPT (125 mg/kg) was given IP One hour later, mice in the vehicle group were given an IP injection of PBS, and mice in the leptin group were given an IP injection of leptin (5 mg/kg). Four hours later (about 8 hours from the first α-MPT injection), mice in the vehicle and leptin groups were euthanized and their livers were flash frozen. In a separate experiment, 6-week-old male Lepob/ob mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (designated baseline, vehicle, and leptin group). Mice were subjected to the same experimental protocol as described above except that the initial 24-hour fasting was omitted. Instead, Lepob/ob mice in the baseline group were fasted for 6 hours before tissue harvesting, and mice in the vehicle and leptin (3 mg/kg) groups were deprived of food at the start of the α-MPT treatment until tissue harvesting. For examination of the effects of AgRP administration, previously ad libitum fed mice were deprived of food and received an intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of aCSF (2 μL) or mouse AgRP82–131 (5 µg; Phoenix) 1 hour after the first IP α-MPT injection. Three hours after this i.c.v. injection, a second dose of α-MPT (125 mg/kg) was given IP Mice were euthanized 6 hours after i.c.v. injection. Hepatic norepinephrine content was measured using a norepinephrine ELISA kit (ALPCO; catalog no. 17-NORHU-E01-RES) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, frozen liver tissues were cut, weighed, and immediately homogenized. All samples were run in duplicates on the same ELISA plate and read at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Specific statistical methods for specific experiments are described in figure legends. A Student t test was used to test the difference between two independent groups of mice. When four different genotypes were compared, one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was used. In cases where the same animals were analyzed over time, repeated-measures two-way ANOVA was used. Statistical analyses were assessed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and JMP (SAS Institute). All analyses were two-tailed. The specific statistical method for each experiment is described in the figure legends.

Results

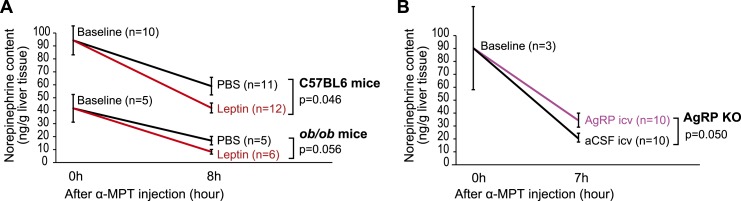

Leptin stimulates hepatic sympathetic activity, whereas AgRP inhibits it

We first investigated the effects of leptin and AgRP on hepatic SNS activity. Hepatic SNS activity was evaluated by measuring tissue norepinephrine content over time after blocking norepinephrine synthesis with a tyrosine hydroxylase inhibitor (α-MPT) (28, 29). In this assay, a greater α-MPT–induced decline in hepatic norepinephrine levels is indicative of greater norepinephrine turnover and hence higher SNS activity.

To analyze leptin’s effects on hepatic SNS activity, 9-week-old male wild-type C57BL/6J mice were divided into three weight-matched groups, which we termed baseline, PBS (vehicle), or leptin, respectively. Mice in all three groups were fasted for 24 hours to markedly lower endogenous leptin levels. At the end of the fast, livers were harvested from the baseline group and flash frozen. Mice in the vehicle and leptin groups were instead given IP injections of α-MPT (250 mg/kg) to block norepinephrine biosynthesis, followed by IP injections of PBS (vehicle group) or leptin (5 mg/kg, leptin group). The fast was continued following these treatments to avoid any potential confounding effects of feeding in the context of leptin treatment. The livers of these mice from both the vehicle and leptin groups were harvested 8 hours after α-MPT treatment. Consistent with the hypothesis, leptin administration led to a greater decline of hepatic norepinephrine content following blockade of norepinephrine biosynthesis, indicative of increased hepatic SNS activity (Fig. 1A, C57BL/6 mice).

Figure 1.

Leptin stimulates and AgRP inhibits hepatic sympathetic activity. (A) Nine-wk-old male C57BL6/J mice were treated with leptin or PBS (vehicle) and subjected to norepinephrine turnover assay (n = 10 to 12 per group as indicated on the graphs). In a separate experiment, 6-wk-old male Lepob/ob mice were injected with PBS or leptin and subjected to norepinephrine assay (n = 5 to 6 per group as indicated on the graphs). (B) AKO were infused i.c.v. with 5 µg of AgRP peptide (82–131 amide) or aCSF (vehicle) and subjected to norepinephrine turnover assay (n = 10 per group for aCSF and AgRP, n = 3 for baseline). P values and the groups being compared are indicated on the graphs. A Student t test was used to compare two independent groups.

Additionally, a parallel experiment was carried out in 6-week-old male Lepob/ob mice. Mice were subjected to the same protocol as were wild-type mice, except that the Lepob/ob mice in the baseline group were fasted for 6 hours before tissue harvesting, and the mice in the vehicle and leptin (3 mg/kg) groups were deprived of food at the start of the α-MPT treatment until tissue harvesting. Notably, leptin treatment exerted a similar effect in Lepob/ob mice as in wild-type mice (Fig. 1A, ob/ob mice), supporting the notion that leptin stimulates hepatic SNS activity.

We next tested the effect of i.c.v. administration of AgRP on hepatic SNS activity. We first validated the biological effects of AgRP by measuring food intake and body weight after a single i.c.v. injection of an active AgRP peptide (82–131 amide) into the lateral ventricle through a guide cannula. The effectiveness of this AgRP peptide was confirmed by its potent capacity to increase both food intake and body weight (Supplemental Fig. 1). To evaluate the effects of AgRP on hepatic SNS activity, AKO were divided into weight-matched groups, injected IP with α-MPT, deprived of food, and subsequently injected i.c.v. with either AgRP (82–131 amide) or aCSF 1 hour after α-MPT injection. The livers of these mice were harvested 7 hours after α-MPT administration. When compared with aCSF, central AgRP administration resulted in a slower decline of hepatic norepinephrine levels following α-MPT treatment, suggesting that AgRP acts in the brain to inhibit hepatic SNS activity (Fig. 1B). In contrast, we did not observe differences in hepatic norepinephrine contents upon i.c.v. injection of AgRP or aCSF into 9-week-old wild-type C57BL/6J mice (aCSF, 22.4 ± 4.2 ng/g tissue; AgRP, 20.6 ± 5.0 ng/g tissue; n = 7 per group). One potential explanation may be that endogenous AgRP in wild-type mice increases during the 7 to 8 hours of fasting time, which may reduce sensitivity to exogenous AgRP.

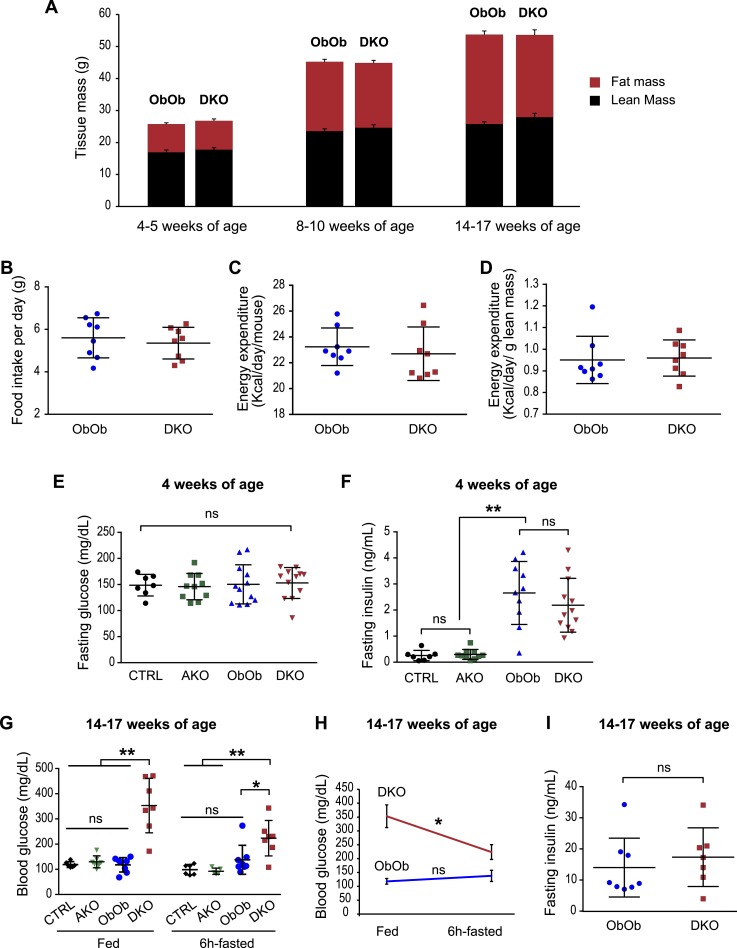

Loss of AgRP does not affect food intake, energy expenditure, or body weight in leptin-deficient mice

To examine the role of AgRP in mediating leptin actions more broadly, we generated mice that were doubly deficient for leptin and AgRP (DKO: Lepob/ob, Agrp−/−) and compared these mice with littermate controls that only lacked leptin (ObOb: Lepob/ob, Agrp+/+ or Lepob/ob, Agrp+/−). Both DKO and ObOb mice developed severe obesity and to the same extent, as revealed by similar fat mass and lean mass assessed at several different ages (Fig. 2A). These data were corroborated by the finding that both DKO and ObOb controls had similar food intake and total energy expenditure when assessed in a CLAMS (Fig. 2B–2D). Thus, AgRP deficiency does not reverse the impact of leptin deficiency on global energy balance.

Figure 2.

Loss of AgRP function in leptin-deficient mice does not affect food intake, energy expenditure, and body weight, and it does not improve glycemic control. (A) Mice that were doubly deficient for leptin and AgRP (DKO: Lepob/ob, Agrp−/−) had similar lean and fat mass compared with mice deficient in leptin (ObOb: Lepob/ob, Agrp+/+ or Lepob/ob, Agrp+/−) at several ages as indicated (n = 7 to 10 per group). (B–D) Ad libitum–fed 8- to 10-wk-old DKO and ObOb mice were measured by CLAMS. Food intake was not different between the two genotypes. Energy expenditure, per animal or normalized with lean mass, was also similar. A Student t test was used to compare two independent groups. (E and F) Six-hour fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels for male CTRL (Agrp+/+ and Agrp+/−), AKO (Agrp−/−), ObOb (Lepob/ob, Agrp+/+; or Lepob/ob, Agrp+/−), and DKO (Lepob/ob, Agrp−/−) mice at 4 wks of age. Each dot represents one mouse. (G–I) Fed and 6-hr fasting insulin and blood glucose for male CTRL, AKO, ObOb, and DKO mice at 14 to 17 wk of age. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. For (E), (F), and (G), a one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was used to compare the four genotypes under either fed or fasted condition. For (H) and (I), a Student t test was used to compare two independent groups under a specific condition (fed or fasted). For (H), a Student paired t test was used to compare fed and fasting glucose of the same mice in each genotype. ns, not significant.

Loss of AgRP does not improve glycemic control in leptin-deficient mice

At 4 weeks of age, both male ObOb and DKO mice remained euglycemic despite having similar degrees of hyperinsulinemia, when compared with lean wild-type mice or AKO (Fig. 2E and 2F). Soon afterward, a subset of ObOb and DKO mice developed hyperglycemia. Surprisingly, adult DKO mice, when examined at 14 to 17 weeks of age, had higher blood glucose levels than did age-matched ObOb mice, and this phenotype was more pronounced under fed conditions than after a 6-hour fast (Fig. 2G and 2H). Plasma insulin levels after a 6-hour fast were not significantly different (Fig. 2I). Thus, in contrast to the commonly held idea, the absence of AgRP does not improve glucose homeostasis in leptin-deficient male mice.

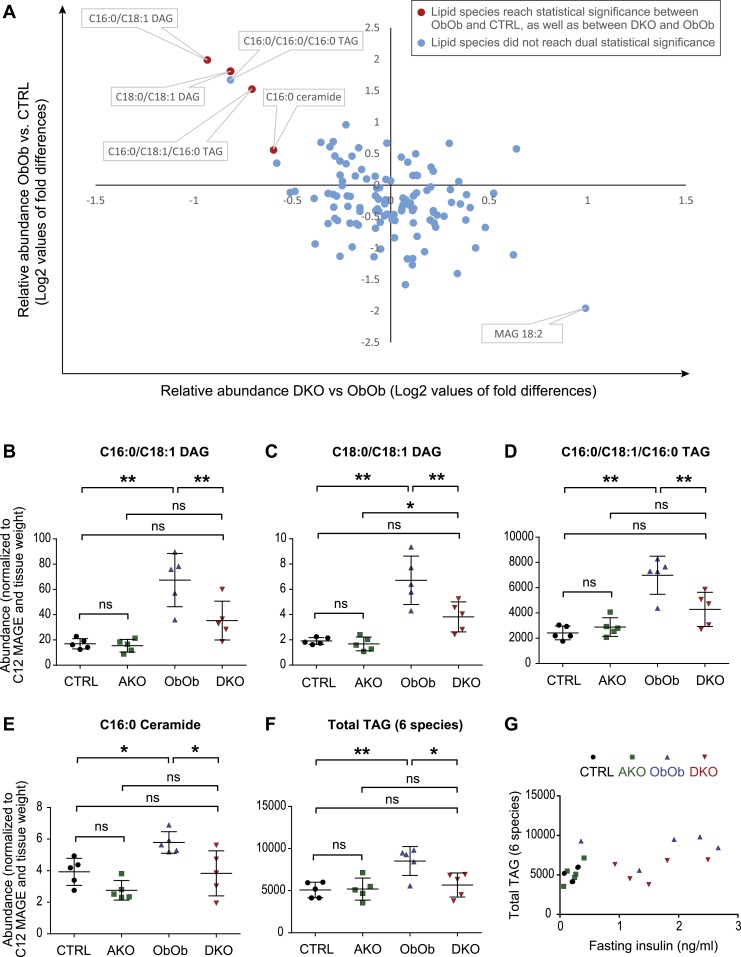

AgRP deficiency reduces hepatic lipid content in young prediabetic leptin-deficient mice

Sympathetic input to the liver is a regulator of hepatic lipid metabolism. Given that we found that leptin increases hepatic SNS and that AgRP reduces it, and because leptin deficiency is associated with severe hepatic steatosis, we next evaluated whether AgRP deficiency would reduce hepatic steatosis. To circumvent the confounding effects of hyperglycemia on lipid accumulation, as might be present in older mice, we examined hepatic lipid composition in 4-week-old prediabetic ObOb and DKO mice, along with their leptin-expressing nonobese controls [Agrp+/+ and Agrp+/− mice (designated as CTRL), and Agrp−/− mice (designated as AKO)]. Hepatic lipids were analyzed using a lipidomics platform. The complete lipidomics data sets are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Of the 111 different lipid species examined, levels of 4 lipid species, that is, C16:0/C18:1 diacylglycerol (DAG), C18:0/C18:1 DAG, C16:0/C18:1/C16:0 triacylglycerol (TAG), and C16:0 ceramide (red data points in Fig. 3A), were significantly different in the livers of ObOb vs CTRL, and also DKO vs ObOb mice. Specifically, the hepatic levels of each of these four lipid species were similar in CTRL and AKO mice, elevated in ObOb mice, and partially normalized in DKO mice (Fig. 3B–3E). Taken together, these data suggest that the increased abundance of these particular lipid species in leptin deficiency is at least partially mediated by AgRP.

Figure 3.

Lack of AgRP function leads to reduced hepatic lipids in young prediabetic leptin-deficient mice. (A) Lipidomics analysis of liver tissues from 4-wk-old male CTRL (Agrp+/+ and Agrp+/−), AKO (Agrp−/−), ObOb (Lepob/ob, Agrp+/+ or Lepob/ob, Agrp+/−), and DKO (Lepob/ob, Agrp−/−) mice. Liver tissues were harvested after a 6-hr fast. (B–F) Neutral lipids and ceramide that are reduced in DKO compared with ObOb mice. (G) Hepatic triglyceride levels in 4-wk-old ObOb and DKO mice do not appear to have a linear relationship with plasma insulin (6 hr fasting). Data are shown as mean ± SD. In (B)–(F), *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons). ns, not significant.

Five other less abundant TAG species (C16:0/C16:0/C16:0 TAG, C16:0/C20:4/C16:0 TAG, C18:0/C18:1/C18:0 TAG, C18:0/C18:0/C18:0 TAG, and C18:0/C20:4/C18:0 TAG) were not different between ObOb and DKO mice. However, the combined hepatic TAG mass (all six species measured by lipidomics) was reduced in DKO mice compared with ObOb mice (Fig. 3F), and this effect was independent of plasma insulin levels (Fig. 3G). In total, these data indicate that AgRP mediates the increased hepatic lipid content seen in young prediabetic leptin-deficient mice, primarily by increasing levels of specific neutral lipid species (TAG), and that AgRP also regulates the hepatic levels of less abundant lipid species with signaling capabilities (e.g., specific DAGs and ceramides).

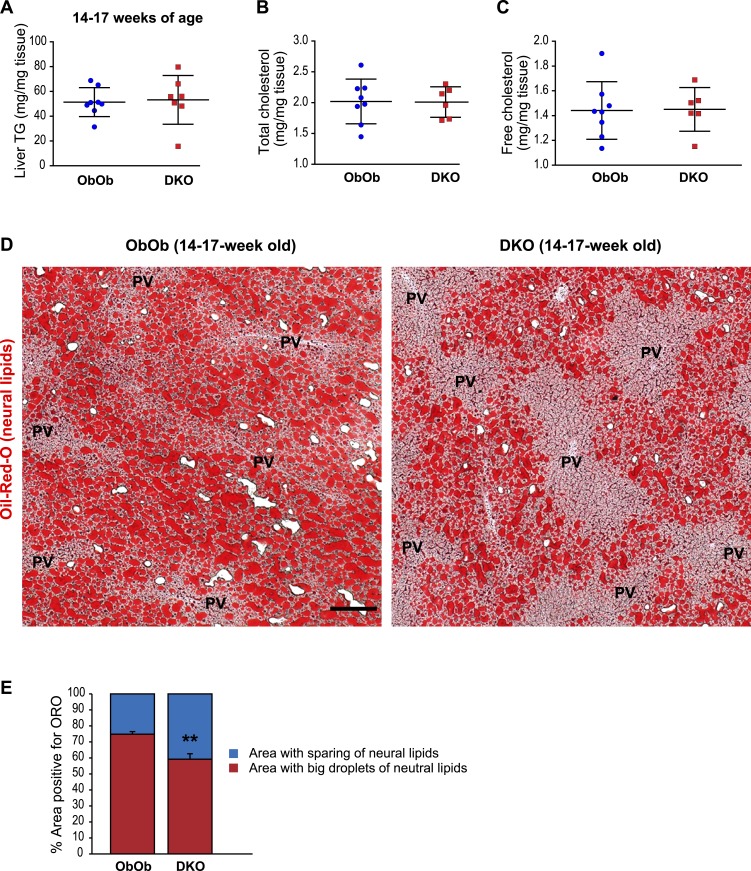

AgRP deficiency in older leptin-deficient mice does not alter overall abundance but shifts the zonal distribution of hepatic neutral lipids

We next examined the role of AgRP on hepatic lipid content in older (14- to 17-week-old) ObOb and DKO mice, an age at which DKO mice had higher blood glucose levels than did ObOb mice (Fig. 2G). In conjunction with this relative rise in blood glucose, total hepatic TAG levels in these older DKO mice rose to a point that was now comparable to that seen in ObOb mice (Fig. 4A). Total cholesterol and free cholesterol contents were also similar between ObOb and DKO mice at this age (Fig. 4B and 4C).

Figure 4.

Absence of AgRP function in adult leptin-deficient mice does not affect the abundance of hepatic neutral lipids but alters their zonal distribution in the liver lobules. (A–C) Liver triglyceride, total cholesterol, and free cholesterol levels of male ObOb (Lepob/ob, Agrp+/+ or Lepob/ob, Agrp+/−) and DKO (Lepob/ob, Agrp−/−) mice at 14 to 17 wk of age. (D) Representative ORO staining of frozen liver sections (10 µm thick) from ObOb and DKO mice at 14 to 17 wk of age showing lipid sparing around the periportal regions. One most diabetic DKO mouse had little ORO signal in the liver and was excluded from the analysis. Scale bar, 200 µm. (E) Quantification of percentage surface areas that contained ORO-positive lipid droplets in liver sections (10 µm) from ObOb and DKO mice at 14 to 17 wk of age showing lipid sparing around the periportal regions. Data are shown as mean ± SD. **P < 0.01 comparing ObOb and DKO mice by a Student t test. PV, portal vein.

In contrast, staining liver sections from these mice with ORO, which visualizes neutral lipids, including DAG, TAG, and cholesteryl esters, revealed differences between the two genotypes. Whereas large lipid droplets were found in hepatocytes surrounding the central veins in both ObOb and DKO mice, DKO mice showed a marked reduction in lipid abundance in the periportal region, representing zone 1 of liver lobules (Fig. 4D and 4E). Of note, 4-week-old DKO mice also had less lipid deposition in the periportal hepatocytes compared with age-matched ObOb mice (Supplemental Fig. 2). Given the absence of obesity, few ORO signals were present in the livers of CTRL and AKO mice, and as such we could not discern any differences in zonation patterns between the two groups (Supplemental Fig. 3). Taken together, these results indicate that the absence of AgRP leads to reduced lipid deposition specifically in the periportal regions under the condition of leptin deficiency.

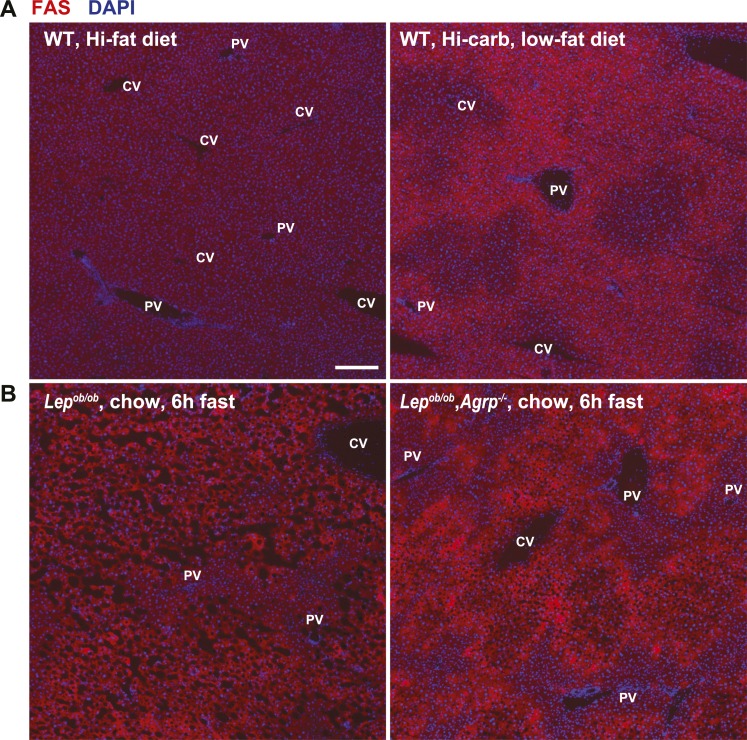

Hepatic steatosis in Lepob/ob mice is associated with increased expression of genes involved in de novo lipogenesis, such as FAS (30). To explore a potential mechanism by which AgRP might mediate hepatic steatosis in these mice, we carried out immunohistochemistry to analyze FAS expression in liver sections from ObOb and DKO mice. We first carried out a pilot experiment in wild-type mice acutely fed a high-fat diet, which is known to inhibit de novo lipogenesis, as well as in mice fasted and then refed with a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet, a condition known to markedly stimulate lipogenesis (31). As expected, hepatic FAS expression was suppressed in mice acutely fed a high-fat diet, and markedly induced by refeeding fasted mice with the high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet (Fig. 5A), indicating that we could use immunofluorescence to measure dynamic changes in hepatic FAS expression. With this in mind, we noted, interestingly, that DKO mice had far less hepatic FAS expression, specifically in periportal hepatocytes, than did ObOb mice. These data suggest that the shifts we saw in zonal lipid distribution induced by AgRP deficiency may be a function of a region-specific reduction in FAS expression and associated de novo lipogenesis (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Expression of FAS is reduced in periportal hepatocytes in adult leptin-deficient mice lacking AgRP function. (A) Examination of FAS expression in wild-type mice that were ad libitum fed with a high-fat diet, or fasted and refed with a high-carbohydrate diet for 24 hr. (B) FAS expression in livers of male ObOb (Lepob/ob, Agrp+/+ or Lepob/ob, Agrp+/−) and DKO (Lepob/ob, Agrp−/−) mice at 14 to 17 wk of age. FAS expression is specifically reduced in periportal hepatocytes in DKO mice compared with ObOb mice. Scale bar, 200 µm. CV, central vein; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; PV, portal vein; WT, wild-type.

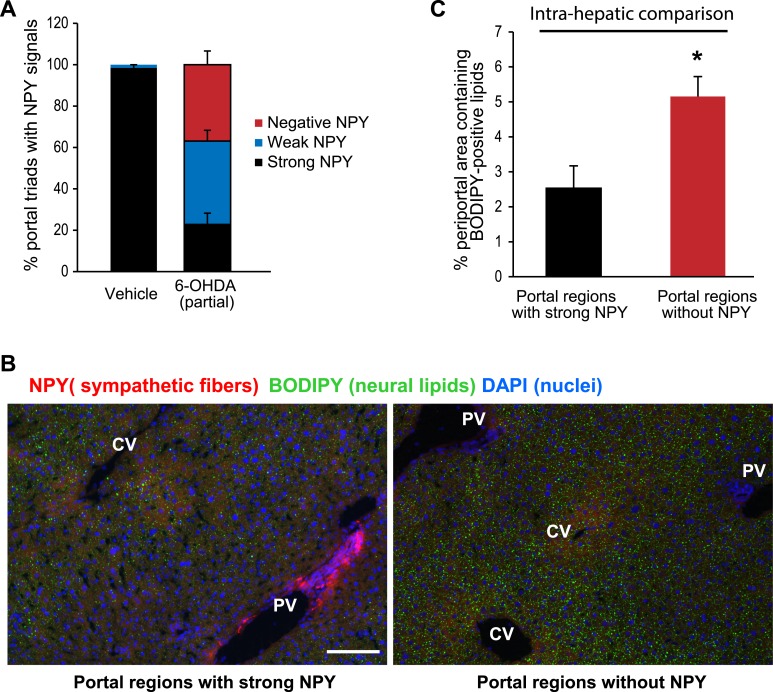

Ablating hepatic sympathetic input alters the zonal distribution of neutral lipids

The liver is heavily innervated by the SNS, and SNS fibers mainly surround the portal triads in rodents (32, 33). In light of our findings indicating that AgRP deficiency influences hepatic lipid zonal distribution, and that AgRP suppressed hepatic SNS activity, we sought to determine the impact of hepatic innervation by the SNS on the zonation of hepatic lipids. Specific and effective denervation of hepatic sympathetic nerves is technically challenging in small animals such as mice. Thus, chemical sympathectomy using 6-OHDA is widely used owing to its established efficacy and technical feasibility (34). However, a major caveat regarding the use of systemic 6-OHDA administration to produce a pervasive hepatic sympathectomy is the potential confounding effect due to ablation of SNS fibers innervating extrahepatic tissues, which may indirectly affect hepatic lipid metabolism via altered hormonal milieu.

To avoid this effect, we produced a partial hepatic sympathectomy in wild-type mice by injecting a moderate amount of 6-OHDA. These mice were subsequently fed a high-fat diet for 3 weeks, after which their livers were harvested and cryosectioned. There were no significant differences in body weight, fat pad weights, blood glucose, or insulin levels between the two groups (Supplemental Fig. 4). Neutral lipids and sympathetic nerve fibers in the livers were simultaneously visualized by BODIPY staining and NPY immunoreactivity, respectively. In vehicle-treated mice, virtually all of the portal triads displayed strong immunoreactivity to NPY. However, in 6-OHDA–treated mice, some of the portal triads displayed a strong NPY signal, whereas others were devoid of any NPY signal (Fig. 6A). To this end, we quantified BODIPY signals from periportal regions with a strong presence of NPY-positive fibers and compared these with BODIPY signals from other periportal regions within the same liver where there was no NPY immunoreactivity, indicative of sympathetic ablation. The partial sympathectomy and intrahepatic comparison were performed to minimize potential influence of circulating factors that may result from sympathetic ablation in extrahepatic tissues. This comparison revealed that ablating hepatic SNS fibers innervating a given portal triad increases the corresponding local periportal BODIPY signal (Fig. 6B and 6C), suggesting that hepatic SNS activity preferentially limits hepatic lipid deposition in periportal hepatocytes.

Figure 6.

Ablation of sympathetic nerves in liver lobules alters zonal distribution of neutral lipids. (A) Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were injected with 6-OHDA (100 mg/kg, 3 injections in 1 wk) or vehicle (0.1% w/v, ascorbic acid) and subsequently placed on a high-fat diet (60 kcal%, D12492, Research Diets) for 3 wk. Livers were harvested after a 6-hr fast, flash frozen, and cryosectioned (10 µm). Immunofluorescence analysis was carried out using a NPY polyclonal antibody to reveal sympathetic fibers innervating the portal triads of liver lobules. The number of portal triads with strong, weak, and negative NPY signals was quantified in vehicle and 6-OHDA–treated mice. (B) Representative images showing lipid accumulation (green, BODIPY signals) around a portal triad with strong NPY-positive SNS fibers (red signals) (left panel) and a portal triad from the same liver without NPY-positive SNS fibers. Scale bar, 100 µm. CV, central vein; PV, portal vein. (C) Comparison of BODIPY signals in portal regions with strong NPY signals with those without NPY signals from the same liver. *P < 0.05 by two-way ANOVA. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Discussion

Proper regulation of whole-body energy metabolism requires precise coordination between the brain and peripheral tissues. In this regard, leptin acts as an adiposity signal to convey the body’s energy status to central nervous system neurons, which in turn regulate appetite, energy expenditure, and storage and utilization of metabolic fuels such as glucose and lipids. In times of energy excess, the liver stores glucose in the form of glycogen and assembles and exports lipids within lipoproteins. During food deprivation, the liver is essential in producing both glucose and ketones to meet the energy demands of the brain and other tissues. Thus, an adipose–brain–liver regulatory circuit is needed to coordinate whole-body energy metabolism in response to dynamic changes in nutritional status. Among hypothalamic neurons, AgRP neurons are uniquely positioned outside the BBB, and they are able to sense and respond to dynamic changes in circulating leptin levels compared with other hypothalamic neurons that reside inside the BBB (7). Expression of AgRP, the defining component of AgRP neurons, is markedly upregulated in leptin-deficient Lepob/ob mice (4). In this study, we provide evidence that AgRP is not a necessary downstream effector of leptin with respect to food intake and energy expenditure, but that it rather mediates hepatic steatosis in the context of leptin deficiency. Thus, our study highlights an adipose–brain–liver regulatory circuit, involving leptin, hypothalamic AgRP, and the SNS, in regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism.

AgRP and NPY, common components of AgRP neurons, have long been considered key downstream targets of leptin. Interestingly, although mice lacking NPY exhibit normal feeding and body weight, NPY deficiency in Lepob/ob mice leads to reduced food intake, increased energy expenditure, and lower body weight (14). In direct contrast, we show that the loss of AgRP in Lepob/ob mice has no effect on food intake, energy expenditure, or body weight. Similarly, most of the orexigenic effects from activating AgRP neurons are attributed to NPY and GABA, but not to AgRP (11–13). Taken together, these findings indicate that whereas NPY is a key leptin-dependent regulator of energy balance, AgRP mediates a distinct aspect of leptin’s actions.

In addition to regulating energy balance, leptin and the central melanocortinergic neurons are known to affect glucose metabolism independent of food intake and body weight (35–37). For example, acute activation of AgRP neurons impairs systemic insulin sensitivity by regulating glucose uptake in brown adipose tissue, but this effect is independent of melanocortin signaling (38). AgRP itself has been implicated in mediating leptin’s antidiabetic effects in LepR-deficient mice, although these effects vary by sex (15, 16, 39). In the present study, we show that the lack of AgRP in adult Lepob/ob mice does not improve but instead worsens glycemic control. Although sex, genetic backgrounds, and dietary conditions could influence the effects of AgRP on glucose homeostasis, it is noted that arcuate-specific proopiomelanocortin deficiency (with normal pituitary proopiomelanocortin expression) improves glucose tolerance despite obesity and insulin resistance, and this is due to reduced renal SNS activity leading to elevated glycosuria (40, 41). Moreover, wild-type mice centrally infused with AgRP also display improved glucose tolerance and elevated glycosuria after a glucose load (40). Given this, our findings raise the intriguing possibility that the relative hyperglycemia seen in the present study in DKO mice could be due to increased renal SNS activity and reduced glycosuria when compared with ObOb mice. Alternatively, a potential increase in hepatic sympathetic activity may also contribute to the increase in glucose production. These findings also highlight that AgRP may, by regulating SNS activity across multiple peripheral tissues, coordinate whole-body energy and glucose homeostasis in a complex manner. This notion is further supported by the recent findings that leptin regulates sympathetic activities in multiple tissues and organs, in part, by direct actions on AgRP neurons (42).

A key finding of this study is the revelation that AgRP acts via the hepatic SNS to promote hepatic lipid accumulation, but that the impact of this on overall hepatic neutral lipid content diminishes with advancing age. The liver receives dense autonomic innervation (32). In humans and primates, SNS fibers invade deeply into the liver parenchyma (43, 44). In rodents, SNS fibers mainly surround the portal triads, and signals from these fibers are propagated across the hepatic lobule via gap junctions (33). Emerging evidence implicates a role for hypothalamic regulation of the SNS in controlling hepatic lipid metabolism. For example, leptin, acting in the brain, stimulates hepatic α1-adrenergic receptors, leading to the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase and the consequent suppression of triglyceride synthesis (23). It was further shown that perinatal exposure to a high-fat diet leads to reduced hepatic SNS innervation in monkeys (44), suggesting that metabolic dysregulation is associated with impaired SNS input to the liver. We show in the present study that leptin stimulates hepatic sympathetic inputs, whereas AgRP suppresses such inputs. These findings corroborate recent work showing that leptin stimulation of hepatic sympathetic activity is reduced in mice lacking LepR specifically in AgRP neurons (42). Collectively, our studies highlight AgRP as a downstream effector of leptin in regulating the sympathetic control over hepatic lipid metabolism.

Finally, our study reveals that hepatic sympathetic inputs regulate the zonal distribution of lipids within liver lobules. Because SNS fibers preferentially innervate the portal regions of these lobules, the specific reduction of periportal lipid deposition and FAS expression we saw in DKO mice compared with ObOb controls strongly supports the concept that stimulating sympathetic inputs to the liver specifically limits periportal lipid synthesis and accumulation. We point out again that overall hepatic TAG levels were no longer different between DKO and ObOb mice by the time these mice reached 14 to 17 weeks of age. The reasons behind the diminishing effect of AgRP on hepatic lipid content in the context of advancing age are not currently known. One possibility is that the relative hyperglycemia also seen in these older DKO mice may activate lipogenic programs via ChREBP or through increased pulsatile release of insulin postprandially, which may exert lipogenic effects in the liver through activation of SREBP1.

Hepatocytes have specialized functions according to their position along the portocentral axis of the liver-cell plate, giving rise to the term “metabolic zonation.” Metabolic zonation allows opposing or competing metabolic pathways to be carried out simultaneously in hepatocytes within different zones, and these pathways include those governing ammonia detoxification and those involved in glucose, lipid, and xenobiotic metabolism (45). For example, gluconeogenesis mainly occurs in periportal hepatocytes whereas glycolysis takes place in pericentral hepatocytes; similarly, fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis occur at higher rates in periportal hepatocytes (46, 47). Metabolic zonation can be dynamically influenced by changes of nutritional status and diets. A number of factors are known to influence the zonal specialization of metabolic functions, including portal–central gradients of oxygen, nutrients, hormones, and other molecular determinants such as Wnt/β-catenin signaling (27, 48–51). In this study, we provide evidence highlighting a previously unrecognized role for AgRP-dependent regulation of hepatic sympathetic activity in contributing to metabolic zonation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIH/NIDDK) Grant 2R01DK080427-06A1 (to A.W.X.). This work was also partly supported by the Mouse Metabolism Core at the University of California, San Francisco Nutrition Obesity Center (NIH/NIDDK Grant 1P30DK098722-01A1), the Microscopy Core at the University of California, San Francisco Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center (NIH/NIDDK Grant P30 DK63720-06A1), and by the University of California, San Francisco Liver Center (NIH/NIDDK Grant P30 DK026743). This work was also supported in part by the Joseph and Vera Long Foundation (to A.W.X).

Author Contributions: M.T.M., A.V., S.M.L., and E.V. performed experiments and analyzed data. M.T.M., D.K.N., S.K.K., and A.W.X. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AgRP

Agouti-related protein

- AKO

Agrp−/− mice

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- CLAMS

comprehensive laboratory animal monitoring system

- CTRL

Agrp+/+ and Agrp+/− mice

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DKO

double-knockout

- FAS

fatty acid synthase

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- i.c.v.

intracerebroventricular

- LepR

leptin receptor

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- ORO

Oil Red O

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

- TAG

triacylglycerol

- α-MPT

α-methyl-p-tyrosine

References

- 1. Allison MB, Myers MG Jr. 20 years of leptin: connecting leptin signaling to biological function. J Endocrinol. 2014;223(1):T25–T35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedman JM, Mantzoros CS. 20 years of leptin: from the discovery of the leptin gene to leptin in our therapeutic armamentarium. Metabolism. 2015;64(1):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morton GJ, Schwartz MW. The NPY/AgRP neuron and energy homeostasis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(Suppl 5):S56–S62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilson BD, Bagnol D, Kaelin CB, Ollmann MM, Gantz I, Watson SJ, Barsh GS. Physiological and anatomical circuitry between Agouti-related protein and leptin signaling. Endocrinology. 1999;140(5):2387–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van den Top M, Lee K, Whyment AD, Blanks AM, Spanswick D. Orexigen-sensitive NPY/AgRP pacemaker neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(5):493–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Enriori PJ, Evans AE, Sinnayah P, Jobst EE, Tonelli-Lemos L, Billes SK, Glavas MM, Grayson BE, Perello M, Nillni EA, Grove KL, Cowley MA. Diet-induced obesity causes severe but reversible leptin resistance in arcuate melanocortin neurons. Cell Metab. 2007;5(3):181–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olofsson LE, Unger EK, Cheung CC, Xu AW. Modulation of AgRP-neuronal function by SOCS3 as an initiating event in diet-induced hypothalamic leptin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(8):E697–E706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yulyaningsih E, Rudenko IA, Valdearcos M, Dahlén E, Vagena E, Chan A, Alvarez-Buylla A, Vaisse C, Koliwad SK, Xu AW. Acute lesioning and rapid repair of hypothalamic neurons outside the blood-brain barrier. Cell Reports. 2017;19(11):2257–2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van de Wall E, Leshan R, Xu AW, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Liu SM, Jo YH, MacKenzie RG, Allison DB, Dun NJ, Elmquist J, Lowell BB, Barsh GS, de Luca C, Myers MG Jr, Schwartz GJ, Chua SC Jr. Collective and individual functions of leptin receptor modulated neurons controlling metabolism and ingestion. Endocrinology. 2008;149(4):1773–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qian S, Chen H, Weingarth D, Trumbauer ME, Novi DE, Guan X, Yu H, Shen Z, Feng Y, Frazier E, Chen A, Camacho RE, Shearman LP, Gopal-Truter S, MacNeil DJ, Van der Ploeg LH, Marsh DJ. Neither agouti-related protein nor neuropeptide Y is critically required for the regulation of energy homeostasis in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(14):5027–5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu Q, Howell MP, Cowley MA, Palmiter RD. Starvation after AgRP neuron ablation is independent of melanocortin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(7):2687–2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu Q, Boyle MP, Palmiter RD. Loss of GABAergic signaling by AgRP neurons to the parabrachial nucleus leads to starvation. Cell. 2009;137(7):1225–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aponte Y, Atasoy D, Sternson SM. AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(3):351–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Erickson JC, Hollopeter G, Palmiter RD. Attenuation of the obesity syndrome of ob/ob mice by the loss of neuropeptide Y. Science. 1996;274(5293):1704–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Israel DD, Sheffer-Babila S, de Luca C, Jo YH, Liu SM, Xia Q, Spergel DJ, Dun SL, Dun NJ, Chua SC Jr. Effects of leptin and melanocortin signaling interactions on pubertal development and reproduction. Endocrinology. 2012;153(5):2408–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sheffer-Babila S, Sun Y, Israel DD, Liu SM, Neal-Perry G, Chua SC Jr. Agouti-related peptide plays a critical role in leptin’s effects on female puberty and reproduction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(12):E1512–E1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nogueiras R, Wiedmer P, Perez-Tilve D, Veyrat-Durebex C, Keogh JM, Sutton GM, Pfluger PT, Castaneda TR, Neschen S, Hofmann SM, Howles PN, Morgan DA, Benoit SC, Szanto I, Schrott B, Schürmann A, Joost HG, Hammond C, Hui DY, Woods SC, Rahmouni K, Butler AA, Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Tschöp MH. The central melanocortin system directly controls peripheral lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(11):3475–3488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Skibicka KP, Grill HJ. Hypothalamic and hindbrain melanocortin receptors contribute to the feeding, thermogenic, and cardiovascular action of melanocortins. Endocrinology. 2009;150(12):5351–5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Enriori PJ, Sinnayah P, Simonds SE, Garcia Rudaz C, Cowley MA. Leptin action in the dorsomedial hypothalamus increases sympathetic tone to brown adipose tissue in spite of systemic leptin resistance. J Neurosci. 2011;31(34):12189–12197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sohn JW, Harris LE, Berglund ED, Liu T, Vong L, Lowell BB, Balthasar N, Williams KW, Elmquist JK. Melanocortin 4 receptors reciprocally regulate sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons. Cell. 2013;152(3):612–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zeng W, Pirzgalska RM, Pereira MM, Kubasova N, Barateiro A, Seixas E, Lu YH, Kozlova A, Voss H, Martins GG, Friedman JM, Domingos AI. Sympathetic neuro-adipose connections mediate leptin-driven lipolysis. Cell. 2015;163(1):84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tanida M, Yamamoto N, Morgan DA, Kurata Y, Shibamoto T, Rahmouni K. Leptin receptor signaling in the hypothalamus regulates hepatic autonomic nerve activity via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and AMP-activated protein kinase. J Neurosci. 2015;35(2):474–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miyamoto L, Ebihara K, Kusakabe T, Aotani D, Yamamoto-Kataoka S, Sakai T, Aizawa-Abe M, Yamamoto Y, Fujikura J, Hayashi T, Hosoda K, Nakao K. Leptin activates hepatic 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase through sympathetic nervous system and α1-adrenergic receptor: a potential mechanism for improvement of fatty liver in lipodystrophy by leptin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(48):40441–40447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Louie SM, Grossman EA, Crawford LA, Ding L, Camarda R, Huffman TR, Miyamoto DK, Goga A, Weerapana E, Nomura DK. GSTP1 is a driver of triple-negative breast cancer cell metabolism and pathogenicity. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23(5):567–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rottkamp DM, Rudenko IA, Maier MT, Roshanbin S, Yulyaningsih E, Perez L, Valdearcos M, Chua S, Koliwad SK, Xu AW. Leptin potentiates astrogenesis in the developing hypothalamus. Mol Metab. 2015;4(11):881–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mehlem A, Hagberg CE, Muhl L, Eriksson U, Falkevall A. Imaging of neutral lipids by oil red O for analyzing the metabolic status in health and disease. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(6):1149–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Torre C, Perret C, Colnot S. Molecular determinants of liver zonation. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2010;97:127–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spector S, Sjoerdsma A, Udenfriend S. Blockade of endogenous norepinephrine synthesis by alpha-methyl-tyrosine, an inhibitor of tyrosine hydroxylase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1965;147:86–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brodie BB, Costa E, Dlabac A, Neff NH, Smookler HH. Application of steady state kinetics to the estimation of synthesis rate and turnover time of tissue catecholamines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1966;154(3):493–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perfield JW 2nd, Ortinau LC, Pickering RT, Ruebel ML, Meers GM, Rector RS. Altered hepatic lipid metabolism contributes to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in leptin-deficient Ob/Ob mice. J Obes. 2013;2013:296537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Horton JD, Bashmakov Y, Shimomura I, Shimano H. Regulation of sterol regulatory element binding proteins in livers of fasted and refed mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(11):5987–5992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yi CX, la Fleur SE, Fliers E, Kalsbeek A. The role of the autonomic nervous liver innervation in the control of energy metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802(4):416–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seseke FG, Gardemann A, Jungermann K. Signal propagation via gap junctions, a key step in the regulation of liver metabolism by the sympathetic hepatic nerves. FEBS Lett. 1992;301(3):265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kostrzewa RM, Jacobowitz DM. Pharmacological actions of 6-hydroxydopamine. Pharmacol Rev. 1974;26(3):199–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ruud J, Steculorum SM, Brüning JC. Neuronal control of peripheral insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morton GJ, Schwartz MW. Leptin and the central nervous system control of glucose metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(2):389–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xu Y, Elmquist JK, Fukuda M. Central nervous control of energy and glucose balance: focus on the central melanocortin system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1243(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Steculorum SM, Ruud J, Karakasilioti I, Backes H, Engström Ruud L, Timper K, Hess ME, Tsaousidou E, Mauer J, Vogt MC, Paeger L, Bremser S, Klein AC, Morgan DA, Frommolt P, Brinkkötter PT, Hammerschmidt P, Benzing T, Rahmouni K, Wunderlich FT, Kloppenburg P, Brüning JC. AgRP neurons control systemic insulin sensitivity via myostatin expression in brown adipose tissue. Cell. 2016;165(1):125–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu S, Marcelin G, Blouet C, Jeong JH, Jo YH, Schwartz GJ, Chua S Jr. A gut–brain axis regulating glucose metabolism mediated by bile acids and competitive fibroblast growth factor actions at the hypothalamus. Mol Metab. 2018;8:37–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chhabra KH, Adams JM, Fagel B, Lam DD, Qi N, Rubinstein M, Low MJ. Hypothalamic POMC deficiency improves glucose tolerance despite insulin resistance by increasing glycosuria. Diabetes. 2016;65(3):660–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chhabra KH, Morgan DA, Tooke BP, Adams JM, Rahmouni K, Low MJ. Reduced renal sympathetic nerve activity contributes to elevated glycosuria and improved glucose tolerance in hypothalamus-specific Pomc knockout mice. Mol Metab. 2017;6(10):1274–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bell BB, Harlan SM, Morgan DA, Guo DF, Rahmouni K. Differential contribution of POMC and AgRP neurons to the regulation of regional autonomic nerve activity by leptin. Mol Metab. 2018;8:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fukuda Y, Imoto M, Koyama Y, Miyazawa Y, Hayakawa T. Demonstration of noradrenaline-immunoreactive nerve fibres in the liver. J Int Med Res. 1996;24(6):466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grant WF, Nicol LE, Thorn SR, Grove KL, Friedman JE, Marks DL. Perinatal exposure to a high-fat diet is associated with reduced hepatic sympathetic innervation in one-year old male Japanese macaques. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e48119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Katz N, Teutsch HF, Jungermann K, Sasse D. Perinatal development of the metabolic zonation of hamster liver parenchyma. FEBS Lett. 1976;69(1):23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schleicher J, Tokarski C, Marbach E, Matz-Soja M, Zellmer S, Gebhardt R, Schuster S. Zonation of hepatic fatty acid metabolism—the diversity of its regulation and the benefit of modeling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851(5):641–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hijmans BS, Grefhorst A, Oosterveer MH, Groen AK. Zonation of glucose and fatty acid metabolism in the liver: mechanism and metabolic consequences. Biochimie. 2014;96:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jungermann K, Katz N. Functional specialization of different hepatocyte populations. Physiol Rev. 1989;69(3):708–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gebhardt R. Metabolic zonation of the liver: regulation and implications for liver function. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;53(3):275–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jungermann K. Zonation of metabolism and gene expression in liver. Histochem Cell Biol. 1995;103(2):81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gebhardt R, Matz-Soja M. Liver zonation: novel aspects of its regulation and its impact on homeostasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(26):8491–8504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.