Abstract

Behavioral adaptation to periods of varying food availability is crucial for survival, and agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons have been associated with entrainment to temporal restricted feeding. We have shown that carnitine acetyltransferase (Crat) in AgRP neurons enables metabolic flexibility and appropriate nutrient partitioning. In this study, by restricting food availability to 3 h/d during the light phase, we examined whether Crat is a component of a food-entrainable oscillator (FEO) that helps link behavior to food availability. AgRP Crat knockout (KO) mice consumed less food and regained less body weight but maintained blood glucose levels during the 25-day restricted feeding protocol. Importantly, we observed no difference in meal latency, food anticipatory activity (FAA), or brown adipose tissue temperature during the first 13 days of restricted feeding. However, as the restricted feeding paradigm progressed, we noticed an increased FAA in AgRP Crat KO mice. The delayed increase in FAA, which developed during the last 12 days of restricted feeding, corresponded with elevated plasma levels of corticosterone and nonesterified fatty acids, indicating it resulted from greater energy debt incurred by KO mice over the course of the experiment. These experiments highlight the importance of Crat in AgRP neurons in regulating feeding behavior and body weight gain during restricted feeding but not in synchronizing behavior to food availability. Thus, Crat within AgRP neurons forms a component of the homeostatic response to restricted feeding but is not likely to be a molecular component of FEO.

Carnitine acetyltransferase is required in AgRP to maintain body weight and feeding behavior but not the synchronization to food availability during chronic daytime restricted feeding.

In an environment with limited food resources, it is crucial to synchronize behavior and metabolism to times when food is available to maximize energy intake and storage. The field of chronobiology describes a food-entrainable oscillator (FEO), made up of several neuronal populations throughout the brain that are broadly responsible for energy homeostasis, wakefulness, and reward and that adjust physiology and metabolism to temporally match available food sources (1–3). Indeed, various brain regions, including the arcuate nucleus, dorsomedial hypothalamus, parabrachial nucleus, and the nucleus of the solitary tract, show c-fos activation in food-entrained mice before the expected meal, even after they returned to ad libitum feeding (4).

The FEO provides a mechanism, based on the integration of metabolic feedback information, to predict future meals and allow the effective metabolism of incoming nutrients and the maintenance of energy homeostasis (2, 3). The integration of feedback is provided, in part, by agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons, which adjust their activity in a feeding- and nutrient-dependent manner (5–9). AgRP neurons are active during energy deficit and drive behavioral changes in a low caloric environment by causing food intake to be increased when food is available, thus motivating food-seeking behavior and locomotor activity when food is unavailable (10, 11). Therefore, it is not surprising that ablating AgRP neurons diminished food anticipatory activity (FAA) and impaired the adaptation to restricted feeding (12). These studies indicate that AgRP neurons function as an FEO; however, how AgRP neurons identify a state of metabolic need at a molecular level is not fully explored. This function involves the efficient substrate switching from fatty acid to glucose oxidation during the transition from fasting to refeeding, because this represents an acute metabolic change associated with food availability. This is particularly important in a restricted feeding paradigm, when food availability is defined by set times.

Carnitine acetyltransferase (Crat) controls mitochondrial acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) levels, a common metabolic intermediate from glucose catabolism and fatty acid oxidation. This is crucial for the normal processing of incoming glucose (e.g., as occurs during refeeding after a fast), because the inability to regulate intracellular acetyl-CoA inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase and reduces intracellular glucose metabolism (13, 14). Indeed, Crat deletion in skeletal muscle impairs substrate switching from fatty acid oxidation to glucose oxidation during a fast/refeeding transition in mice due to decreased pyruvate dehydrogenase activity (15). We described recently that AgRP neurons require Crat to mediate adaptive changes during fasting and refeeding and subsequently control peripheral nutrient partitioning (16). These studies show that mice lacking Crat in AgRP neurons [knockout (KO) mice] lack the metabolic flexibility to effectively switch from fatty acid use to glucose use during the transition from fasting to refeeding, as seen in wild-type (WT) mice.

The actions of Crat to regulate cellular function during a fast/refeeding transition make it an ideal enzyme to convey information about nutrient availability to AgRP neurons, which underlies a potential role as a FEO. AgRP neurons have recently been described as “energy calculators” (8), which function to pass on metabolic information to various parts of the brain to influence physiology and behavior. Given that AgRP neurons can act as FEOs (12), it is not surprising that AgRP neurons communicate a rise in glucose levels to the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the master clock regulating circadian rhythms (17). However, to our knowledge, the molecular mechanisms within AgRP neurons that enable them to act as an FEO have not been addressed.

We hypothesized that the handling of incoming nutrients associated with the fast/refeeding transition via Crat provides a mechanism to integrate metabolic feedback for circadian entrainment and FEO function in AgRP neurons. Here, we report that deleting Crat in AgRP neurons affects adaptation to restricted feeding by reducing food intake, which results in lower body weight and brown adipose tissue (BAT) temperature and increased FAA.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experiments were conducted in compliance with the Monash University Animal Ethics Committee guidelines. Male mice were kept at standard laboratory conditions with free access to food (chow diet; catalog no. 8720610; Barastoc Stockfeeds, Victoria, Australia), and water at 23°C in a 12-hour light-dark cycle and were group housed to prevent isolation stress, unless otherwise stated. Mice were 8 to 11 weeks old and weight matched (average weight, WT control mice, 27.0 g; AgRP Crat KO mice, 26.3 g) for experiments. AgRP-ires-cre mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME; AgRPtm1(cre)Low/J; stock no. 012899; RRID: IMSR_JAX:012899) and bred with NPY GFP mice [B6.FVB-Tg(Npy-hrGFP)1Lowl/J; stock no. 006417; RRID: IMSR_JAX:006417; The Jackson Laboratory]. AgRP-ires-cre::NPY GFP mice were then crossed with Cratfl/fl mice (RRID: MGI:5427430) donated by Randall Mynatt (Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA) to delete Crat from AgRP neurons (AgRP Crat KO). All mice were on a C57BL6J background as a result of more than six generations of backcrossing. Experimental mice were bred by crossing AgRP cre heterozygote::Cratfl/fl mice with AgRP wt::Cratfl/fl mice, producing a 1:1 ratio of cre-positive and cre-negative offspring; as such, littermates were used in the experimental groups.

Telemeter surgery

Single-housed mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and anesthesia was maintained by constant nasal delivery of 2.5% isoflurane. Each animal received 50 μL meloxicam (0.25 mg/mL; Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany) before the surgery to minimize postsurgery pain. Telemeter probes were inserted into the scapular BAT and fixated in the surrounding fat tissue. Telemetric data were recorded with VitalView (RRID: SCD_014497; STARR Life Science, Oakmont, PA). After 7 days’ recovery, mice were transferred into BioDAQ feeding cages (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ).

Feeding experiment

After 48 hours’ acclimation to the feeding cage environment, ad libitum food intake was monitored for 6 days before restricting access to food to 3 hours during the light phase [Zeitgeber time (ZG) 4 to 7]. Body weight and blood glucose level were measured daily before the feeding period. After 26 days, mice were culled 1 hour before or 2 hours after access to food; tissues were dissected and frozen at −80°C.

Analysis of blood chemistry

Acylated and des-acylated ghrelin (Mitsubishi Chemical Medience, Tokyo, Japan), glucagon (Yanaihara Institute, Shizuoka, Japan), corticosterone (Abnova, Heidelberg, Germany), nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) concentration (NEFA C Assay Kit; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), and triglycerides (Triglyceride Assay Kit; Roche) were all measured according to manufacturers’ instructions.

Glucose extraction

The crushed and weighed frozen tissue was digested in KOH at 70°C for 20 minutes. Saturated NaSO4 and 95% ethanol were added, mixed, and centrifuged for 10 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in deionized water and digested at 70°C for 10 minutes before adding 95% ethanol, mixing, and centrifuging. The precipitate was resuspended in amyloglucosidase buffer (0.3 mg/mL amyloglucosidase in 0.25 M acetate) and incubated at 37°C overnight. Liver glycogen concentrations were determined with a glucose oxidase assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) after glucose extraction.

Liver triglycerides

The crushed and weighed frozen tissue was incubated with a 2:1 chloroform-to-methanol solution overnight. Then, pure chloroform and 0.9% NaCl were added and incubated for 10 minutes on a shaker, followed by a 10-minute centrifugation step at 2000 rpm. The chloroform phase was transferred to a fresh glass tube and evaporated to complete dryness under N2 at 40°C. The dried extract was dissolved in absolute ethanol and triglycerides were determined with the triglyceride assay kit (Roche).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA was extracted using Qiazol (Qiazol Sciences, Hilden, Germany). Briefly, frozen, crushed tissue was dispersed in Qiazol and incubated for 5 minutes before adding chloroform and mixing for 15 seconds using a vortexer. After centrifuging the samples, the upper aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube and incubated with isopropanol for 10 minutes to form a precipitate. The samples were centrifuged and the pellet washed with 75% ethanol and then air dried. The dry RNA pellets were dissolved in Tris-EDTA buffer, and the concentration was measured with a Nano Drop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (catalog no. 170-8890; Bio-Rad Laboratories). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed using SYBR Green Mastermix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a Real Plex4 Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The following primers were obtained from GeneWorks Amplifications: 18S ribosomal RNA 18S (TTCCGATAACGAACGAGACTCT, TGGCTGAACGCCACTTGTC); phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1, cytosol (Pck1; TGCCCAAGGCAACTTAAGGG, CAGTAAACACCCCCATCGCT); glucose-6-phosphatase, catalytic (G6pc; AGTCTTGTCAGGCATTGCTGT, AAAGTCCACAGGAGGTCCAC); glycogen phosphorylase, liver (Pygl; AAGAAGGGGTATGAGGCCAAA, GACACTTGACATAGGCTTCGT); glycogen synthase 2, liver (Gys2; AATGTGAGCCCACCAACGAT, CTTCCAAAATGCACCTGGCA); glycerol kinase (Gk; GCAACCAGAGGGAAACCACA, TAGGTCAAGCCACACCACG); adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl; AGAGCCCATGGTCCTCCGA, AGCAAAGGGTTGGGTTGGTT); glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, mitochondrial (Gpat; CCAGTGAGGACTGGGTTGAC, CTCTGTGGCGTGCAGGAATA); fatty acid synthase (Fasn; TGGGTGTGGAAGTTCGTCAG, CTGTCGTGTCAGTAGCCGAG); citrate synthase (Cs; TGTAGCTCTCTCCCTTCGGT, ACGAGGCAGGATGAGTTCTTG); neuropeptide Y (NPY; CCGCCACGATGCTAGGTAAC, CAGCCAGAATGCCCAAACAC); AgRP (AAGTCTGAATGGCCTCAAGAAGA, GACTCGTGCAGCCTTACACAG); growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR; ATGGGTGTCGAGCGTCTTCTTCTT, CAAACACCACCACAGCAAGCATCT); pro-opiomelanocortin-α (POMC; GCGACGGAAGAGAAAAGAGGT, ATTGGAGGGACCCCTGTCG); glucokinase (Gck; ATGTGCTCAGCAGGACTAGC, AACCGCTCCTTGAAGCTCG); glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh; TCAAGCTCATTTCCTGGTATGACA, TCTTGCTCAGTGTCCTTGCT); pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 α 1 (PDH1; TGCTGGTTGCTTCCCGTAAT, AGCCGATGAAGGTCACATTTCTTA); acetyl-CoA carboxylase α (ACC1; GCTAAACCAGCACTCCCGAT, GCTGGATCTCATGTGAAAGGC); and acetyl-CoA carboxylase β (ACC2; GAACACAAGTGATCCTGAATCTCAC, ATGAGCACCTTCTCTATGACCC).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reactions were performed using a Real Plex4 Mastercycler (Eppendorf). All reactions confirmed a single product of the expected size by melting curve and agarose gel electrophoresis. Reaction efficiencies for primers were >1.90. mRNA levels were expressed using the comparative threshold cycle method normalized to the housekeeping gene.

Data analysis

Activity and BAT temperature recordings were binned into 30-minute intervals in order to provide an average recording for each 30-minute period. For relative change in activity, the average activity during ad libitum access to food was used as baseline (ZG 3 to 4 for FAA, and ZG 12 to 16 for habitual feeding time; dark phase) and expressed as 100%. Change in activity of each day of restricted food access was calculated as the average activity of WT or KO mice during this time and expressed as percentage change from baseline.

Statistical analysis

All data are represented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVAs with Tukey post hoc tests were used to determine statistical significance between treatment and genotype. A two-tailed Student unpaired t test was used when comparing genotype only. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analysis and graphing were conducted using Graphpad Prism (RRID: SCR_002798; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA)

Results

Crat in AgRP neurons was required for adaptation of feeding behavior to restricted feeding

Our previous findings demonstrated that Crat is required for AgRP neurons to acutely sense states of energy deficit during fasting (16). Moreover, AgRP neurons are required for the appropriate adaptation to a state of restricted feeding and to integrate circadian and metabolic cues to facilitate appropriate adaptation (12). To test if Crat in AgRP neurons facilitates adaptation to states of restricted food availability, we placed AgRP Crat WT and KO mice on a restricted feeding paradigm in feeding cages with computer-controlled gating system without the need for human intervention (BioDAQ; Research Diets), whereby they only had access to food for 3 hours per day from 4 to 7 hours into the light cycle (Fig. 1a and 1b).

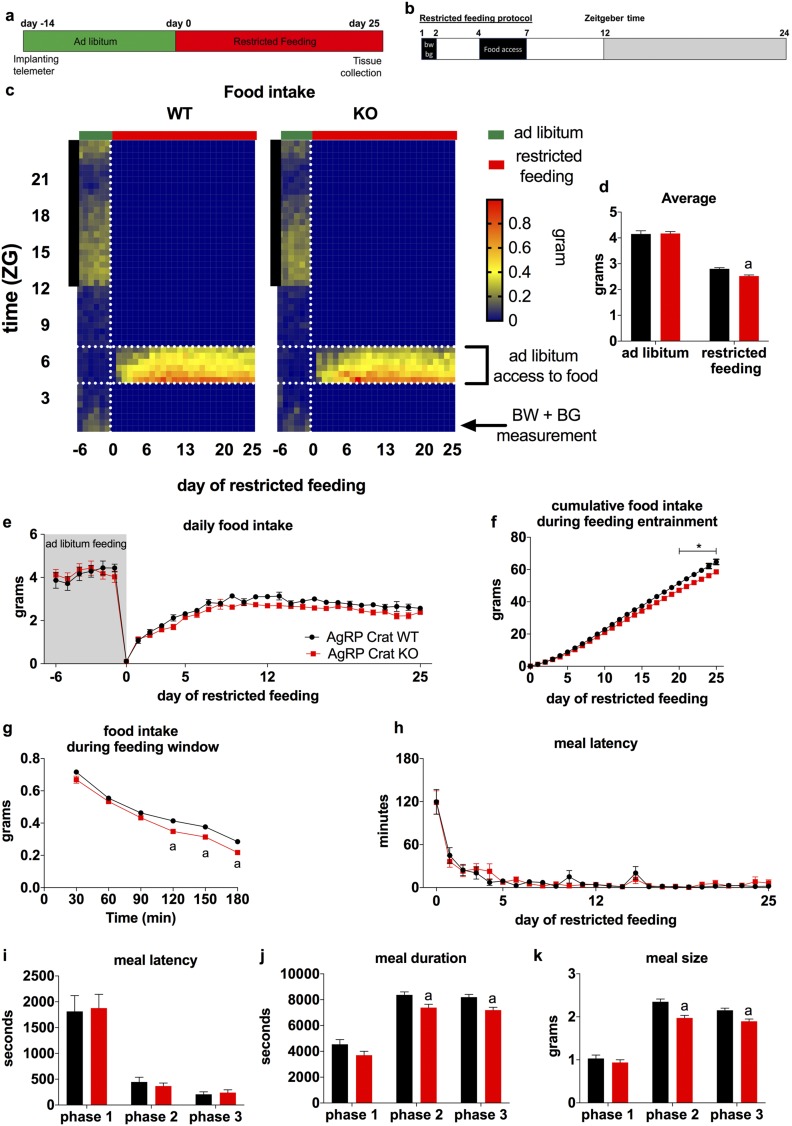

Figure 1.

AgRP Crat KO mice adjusted to feeding entrainment but showed altered feeding behavior. Schematic of the (a) experimental design and (b) the restricted feeding protocol. (c) Heat map depicting food intake in 30-minute bins for 6 days ad libitum and 25 days of restricted feeding. The vertical black bar on left indicates dark phase; the vertical, white, dashed line indicates start of restricted feeding; the horizontal, white, dashed lines frame the feeding window during restricted feeding. (d) Average food intake during ad libitum and food restriction, (e) daily food intake, and (f) cumulative food intake during restricted feeding. (g) Average food intake during the feeding window from days 5 to 25 of restricted feeding. Daily meal latency during the (h) restricted feeding and (i) average latency, (j) duration, and (k) size of the first meal from phase 1 (days 0 to 5), phase 2 (days 6 to 12), and phase 3 (days 13 to 25) of restricted feeding. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 18 to 20. (j and k) aP < 0.05 by two-way (repeated measured, where appropriate) ANOVA with Sidak post hoc analysis. BG, blood glucose; BW, body weight.

In the current study, when we analyzed the feeding behavior (Fig. 1c), we found that adaptation to altered food availability occurred in three stages. Phase 1 (days 0 to 5) was marked by very low food intake, causing rapid body weight loss (Fig. 2a). During phase 2 (days 6 to 12), mice adapted to daytime feeding, increased food intake and feeding time, and, consequently, began to restore body weight. In phase 3 (days 13 to 25), mice were fully adjusted to the new feeding paradigm and food intake in mice plateaued, although mice continued to restore body weight (Fig. 2a).

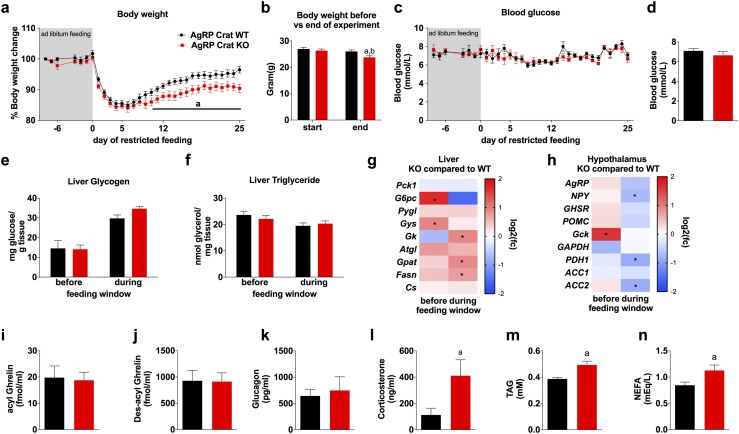

Figure 2.

AgRP Crat KO mice exhibited slower body weight regain on a restricted feeding schedule. Body weight development relative to (a) starting weight and (b) absolute average weight of animals at beginning and end of experiment. (c) Daily blood glucose measured prior to feeding. (d) Plasma glucose, (e) liver glycogen, (f) triglyceride, and (g) liver gene expression in mice after 25 days of restricted feeding before or 2 hours after access to food. (g, h) *P < 0.05, KO vs WT before or during the feeding window. (h) Hypothalamic gene expression profiles of AgRP, NPY, GHSR, POMC, Gck, GAPDH, PDH1, ACC1, and ACC2 from mice after 25 days of restricted feeding before or 2 hours into feeding window. (i) Acyl ghrelin, (j) des-acyl ghrelin, (k) glucagon, (l) corticosterone, (m) plasma triglyceride levels, and (n) NEFA at the end of the experiment (day 25) 1 hour before feeding window. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 8 to 12. (b and l–n) aP < 0.05 vs WT mice at end of experiment; bP < 0.05 vs KO mice at the start of the experiment, by two-way (repeated measured, where appropriate) ANOVA with Sidak post hoc analysis or unpaired t tests.

Throughout the experiment, we found no differences in meal latency, defined as the time passed between opening of the feeding window and meal initiation (Fig. 1h and 1i), but AgRP Crat KO mice ate, on average, less during the 3-hour feeding window over the course of the restricted feeding paradigm (Fig. 1d–1f). This was mostly due to shorter duration (Fig. 1j) and smaller size (Fig. 1k) of the initial meal, resulting in less food intake from 90 to 180 minutes of the 3-hour feeding window (Fig. 1g).

Crat in AgRP neurons affected physiological adaptation to restricted feeding

There was no difference in body weight during the 8-day ad libitum acclimation period; however, restricted feeding during the light phase caused a rapid reduction in body weight from day 0 to day 5, at which time the reduction in body weight plateaued. By day 8 of restricted feeding, AgRP Crat WT and KO mice started to display adaptation to daytime feeding and restore lost body weight. Although both genotypes restored lost body weight, AgRP Crat KO mice gained less body weight from day 10 until the end of the experiment at day 25 (Fig. 2a) and the change in body weight from the beginning of the experiment was significantly greater in KO than in WT mice (Fig. 2b).

Despite the loss in body weight, blood glucose levels remained similar in both genotypes (Fig. 2c and 2d). Our previous studies showed that AgRP Crat KO mice maintain blood glucose levels during fasting through adaptation of liver metabolism (16). Therefore, we sought next to examine if there are changes in liver at the end of the experiment and compared glycogen and triglyceride content and hepatic gene expression before and 2 hours into the feeding window. We found low glycogen levels in fasted mice, which were replenished in the fed state, without differences in genotype (Fig. 2e). Also, liver triglycerides were not different between genotype and did not change with refeeding (Fig. 2f). Under fasted conditions before the feeding window, AgRP Crat KO mice had higher mRNA levels of G6pc, a key enzyme in gluconeogenesis, but we found no genotype differences in other genes involved in endogenous glucose production (Fig. 2g). Interestingly, Gys expression was significantly elevated before, but not during, feeding in KO mice relative to WT mice. Gene expression of enzymes involved in lipid synthesis (i.e., Gk, Gpat, and Fasn) were significantly elevated in the liver of AgRP Crat KO mice during feeding, compared with WT mice (Fig. 2g).

Hypothalamic neurons, including AgRP and MC3R-containing neurons, are crucial for food-entrainable behavior (12, 18, 19). Hence, we also examined mRNA expression of the hypothalamus immediately before and during the feeding window. We found no differences in AgRP, GHSR, or POMC mRNA levels between genotypes. NPY mRNA levels were not significantly different before the feeding window; however, there was a significant decrease in NPY mRNA expression in AgRP Crat KO mice during feeding compared with that in WT mice (Fig. 2h). Gene expression of Gck, well described as a glucose sensor (20–24), was significantly elevated in KO mice before, but not during, the feeding window compared with expression in WT littermates. Expression levels of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDHa1) and ACC2 were not significantly different between genotypes before feeding but were significantly reduced in KO mice during the feeding window. Expression levels of GAPDH and ACC1 were not different between genotype and not affected by feeding (Fig. 2h).

Previous studies have shown an FEO responds to signals from the periphery (1); therefore, we analyzed plasma at the end of the experiment, 1 hour before commencing the feeding period and found no differences in blood glucose levels (Fig. 2d), acyl ghrelin (Fig. 2i), des-acyl ghrelin (Fig. 2j), or glucagon (Fig. 2k), but AgRP Crat KO mice had significantly higher levels of corticosterone (Fig. 2l), triglycerides (Fig. 2m), and nonesterified fatty acid (Fig. 2n).

Crat in AgRP neurons regulated food-seeking activity during restricted food availability

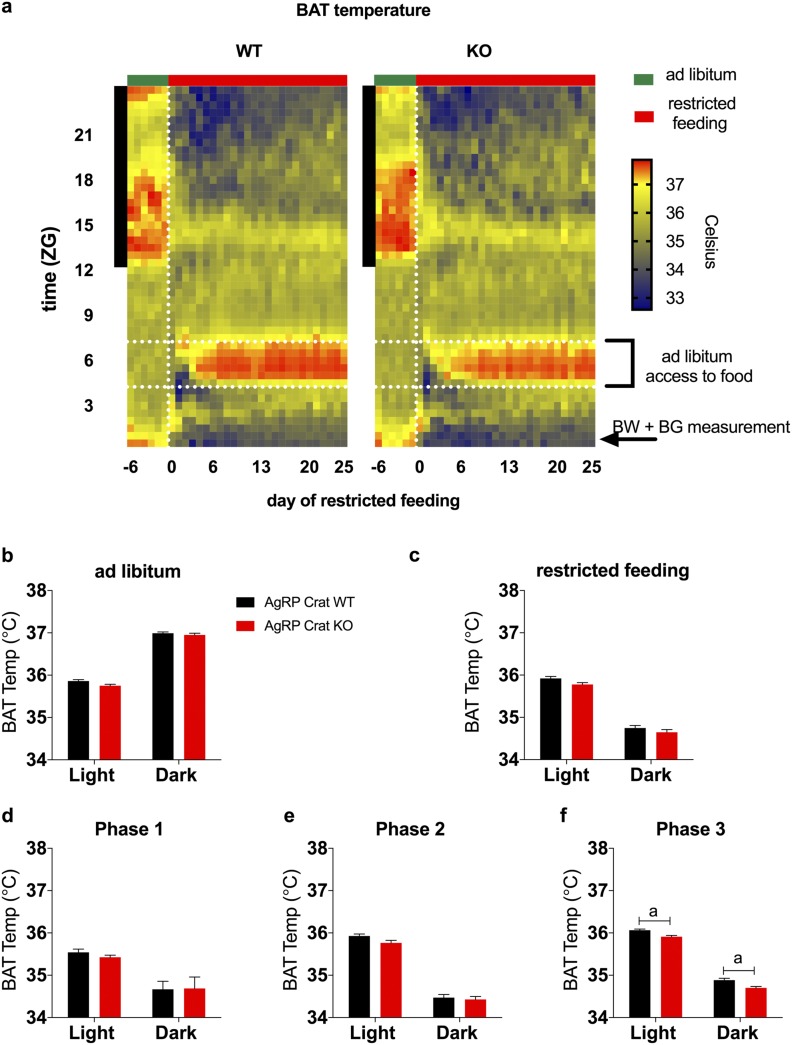

To further investigate adaptive changes in response to the temporal food availability, we implanted telemeter probes into the interscapular BAT to monitor BAT thermogenesis (Fig. 3a) and locomotor activity (Fig. 4a). BAT temperature only diverged after animals adjusted to restricted feeding, in the third phase of the feeding entrainment when both genotypes were regaining body weight (Fig. 3b–3f), most likely a consequence of lower body weight during this phase.

Figure 3.

BAT temperature differed only during the last part of the restricted-feeding paradigm. (a) Heat map depicting BAT temperature in 30-minute bins during ad libitum and restricted feeding. The vertical black bar on left indicates dark phase; the vertical, white, dashed line indicates the start of restricted feeding; the horizontal, white, dashed lines frame the feeding window during restricted feeding. Average BAT temperature during (b) ad libitum and (c) restricted feeding conditions. Average BAT temperature during restricted feeding separated into (d) phase 1, (e) phase 2, and (f) phase 3. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 8 to 10. aP < 0.05 by two-way (repeated measures, where appropriate) ANOVA with Sidak post hoc analysis. BG, blood glucose; BW, body weight.

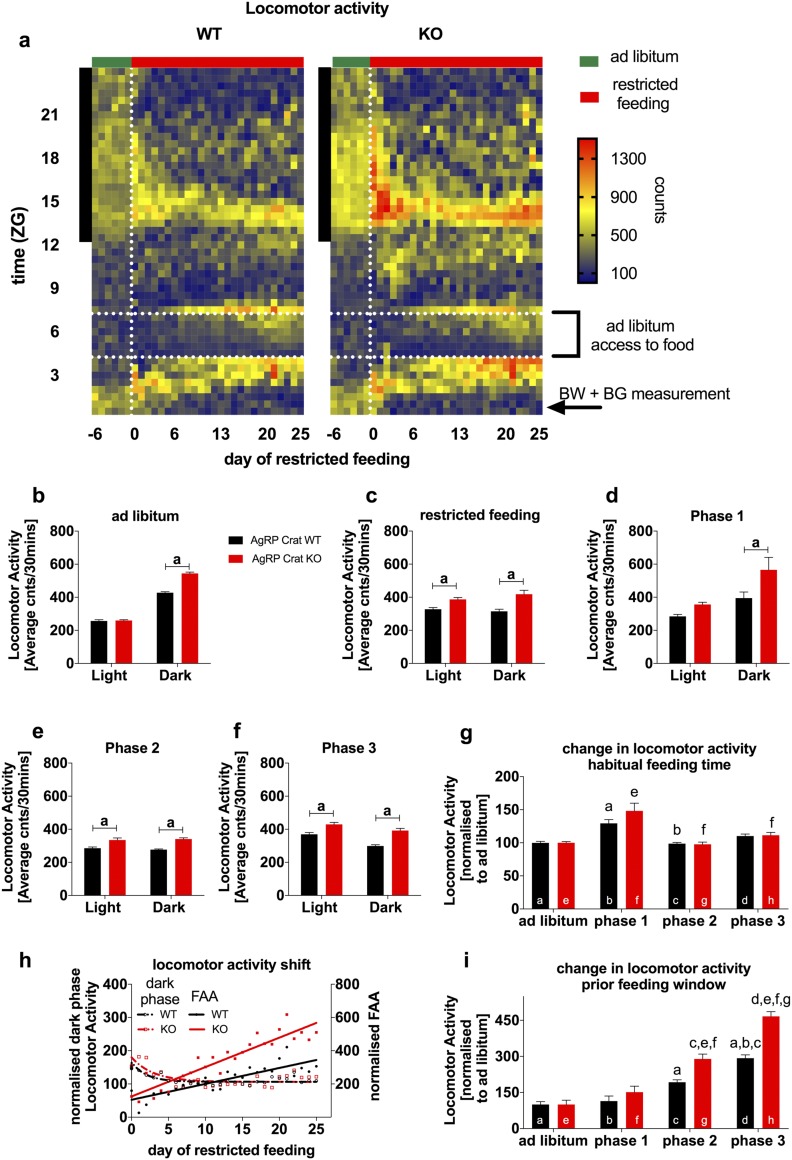

Figure 4.

AgRP Crat KO mice exhibited greater FAA. (a) Heat map depicting locomotor activity in 30-minute bins during ad libitum and restricted feeding. The vertical black bar on left indicates dark phase; the dashed lines frame the feeding window during restricted feeding. Average locomotor activity during (b) ad libitum and (c) restricted feeding conditions. Average locomotor activity during restricted feeding separated into (d) phase 1, (e) phase 2, and (f) phase 3. (g) Change of total locomotor activity during the first 4 hours of dark phase relative to ad libitum conditions. (h) Change in activity per day during ZG 3 to 4 (prior feeding window) and ZG 12 to 16 (beginning dark phase) relative to ad libitum conditions. (i) FAA defined as the total activity 1 hour before the feeding window relative to ad libitum conditions. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 8 to 10. (b–f) aP < 0.05 by two-way (repeated measures, where appropriate) ANOVA with Sidak post hoc analysis; except (g–i) where letters above bars indicate a significant difference between genotype and phase. BG, blood glucose; BW, body weight.

KO mice, under ad libitum conditions, had levels of increased locomotor activity during the dark phase but no differences during the light phase (Fig. 4b). Once food availability was restricted to a few hours during the light phase, mice shifted their activity pattern toward the new feeding time, reduced their activity during the dark phase, and increased activity during the light phase progressively, with KO mice having greater levels of locomotor activity (Fig. 4c–4f).

To account for these differences, we normalized locomotor activity to baseline activity so we could specifically compare changes in locomotor activity provoked by the change in feeding time. Although AgRP Crat KO mice and WT mice developed FAA, AgRP Crat KO mice exhibited significantly increased FAA compared with WT controls (Fig. 4i) after 5 days of restricted feeding in phases 2 and 3. Interestingly, mice show initially increased locomotor activity during the beginning of the dark phase, suggesting increased food seeking behavior during their habitual feeding period (Fig. 4g), which is in line with observations in previous studies (10). As the restricted feeding paradigm developed, mice progressively reduced dark-phase activity and increased FAA (Fig. 4h), displaying an active learning process.

Discussion

AgRP neurons primarily function to conserve energy during periods of food scarcity and replenish energy stores during food availability. Recent evidence also suggests that AgRP neurons are a component of the FEO (4, 12). To effectively function as an FEO, AgRP neurons need to accurately integrate and respond to information about energy deficit and energy availability. We have recently shown that Crat in AgRP neurons is important to regulate the fasting/refeeding transition by effectively enabling substrate switching from fatty acid use to glucose use (16). This enables the preservation of fatty acids for storage as soon as glucose from food consumption becomes available and represents not only an important mechanism of energy conservation but might also be an important component of an FEO. Tan et al. (12) showed that mice lacking AgRP neurons take longer to adapt to a restricted feeding paradigm, causing reduced food intake and reduced body weight during the first 10 days of the restricted feeding paradigm, but they eventually anticipate daytime feeding, increase food intake, and gain body weight similar to WT mice. Our results show AgRP Crat KO mice have shorter and smaller meals during restricted daytime feeding, similar to our previous findings after overnight fast/refeeding (16). This results in reduced food intake, slower body weight gain, and increased FAA after 25 days of restricted feeding. It is important to note, however, that unlike AgRP neuronal ablation (12), AgRP Crat KO mice displayed no deficit in FAA or, importantly, meal latency. Thus, Crat within AgRP neurons forms a component of the homeostatic response to restricted feeding but is not likely to be a molecular component of FEO.

Food availability and consumption during the light phase shifts the periodicity of circadian gene expression, hormonal secretion, and circulating metabolites; and alters brain activity, sleep, and physical activity, as well as meal patterns (25–32). Rodents entrained to daytime feeding show increased locomotor activity before anticipated meal time (33, 34) and this FAA is a crucial adaptation to predicted feeding opportunities (35, 36). Several studies demonstrated that brain regions regulating food intake and energy homeostasis are required for expression of FAA (18, 19, 36–38), and peripheral metabolic signals can modulate and entrain FAA, including ketone bodies, free fatty acids, glucose, ghrelin, leptin, and corticosterone (35, 39–44), of which some signal energy deficit (45). Previous studies have shown that AgRP ablation reduces FAA during the first 3 days of restricted feeding (12); however, AgRP Crat KO mice showed no deficit in FAA at any time of our restricted feeding regimen and, in fact, KO mice exhibited increased FAA during the second and third phase of restricted feeding (days 6 to 25). Moreover, KO mice exhibited lower food intake and had reduced body weight gain, particularly in the third phase. Therefore, we predict the increased FAA manifests because of the greater energy deficit incurred in KO mice at this time. In support of this, greater energy deficit and body weight loss during calorie restriction elicits greater FAA (46–48). Moreover, higher corticosterone and NEFA levels before the feeding window, as seen in our KO mice, correspond with a progressively increasing FAA (42, 44).

Furthermore, KO mice commenced feeding in a timeframe similar to that of WT mice when challenged with restricted food availability, indicating that Crat deletion in AgRP neurons does not affect behavioral synchronization to altered food availability. Also, during the first days of restricted feeding before the development of FAA, WT and KO mice increased food seeking activity at the beginning of the dark phase, their habitual feeding time. This reflects findings from Krashes et al. (10) showing that AgRP neuronal activation in the absence of food increased locomotor activity. In addition, in a proteomic screen of AgRP neurons in our previous study, we found significantly increased levels of proteins associated with circadian entrainment (KEGG pathway 4713) during fasting (16), including mitogen-activated protein kinase, a marker for cellular activity that is associated with FAA (49–51). Together, these findings suggest that deleting Crat in AgRP neurons does not impair synchronization to daytime feeding but sensitizes AgRP neurons to energy deficit.

Despite no deficit anticipating daytime feeding, KO mice reduced meal size and duration leading to reduced overall food intake during the feeding window, a phenomenon we also observed previously during fasting/refeeding experiments (16). Here, we observed lower NPY gene expression in KO mice during feeding, suggesting that the impaired feeding response might be due to a greater reduction of NPY signaling upon refeeding. That rats under a restricted feeding paradigm have high NPY gene expression prior to feeding and reduce NPY gene expression upon refeeding (52) supports this idea. In addition, gene expression of PDHa1 and ACC2, both enzymes dependent on proper functioning of Crat, were significantly reduced during refeeding, demonstrating the importance of Crat in AgRP neurons during refeeding.

Hypothalamic gene expression of Gck, the enzyme phosphorylating glucose during the initial step of glycolysis, was significantly elevated in KO mice before the feeding window, which suggests dysregulated glucose metabolism in AgRP neurons at this time. Indeed, our previous glucose-stimulated glucose uptake experiments showed significantly increased glucose uptake in the hypothalamus 15 minutes after glucose administration in AgRP Crat KO mice (16). Together, these findings emphasize the inability of AgRP Crat KO mice to accurately calculate the caloric value of incoming nutrients and highlight that Crat is crucial for integrating acute changes in metabolic state. The resulting lower food intake represents an impairment to restricted feeding and underlines that Crat in AgRP neurons is a component of the energy-calculating mechanism specifically promoting energy replenishment when food is available.

Increased plasma triglyceride and NEFA levels indicate greater fatty acid use prior to feeding, mimicking our previous findings during fasting/refeeding (16). Therefore, we predict that the lower body weight seen in KO mice is due to lower fat mass as a result of the greater fatty acid use and less food intake during the 25-day restricted feeding paradigm. The lower BAT temperature at the end of the experiment is presumably a consequence of lower body weight during this phase, particularly because no difference in BAT temperature was recorded until well after the body weight differences were observed. This suggests the reduced BAT temperature toward the end of the experiment is an indirect effect to spare energy reserves, consistent with findings of other studies showing thermal adaptation to calorie restriction (53, 54).

Peripheral organs are also under circadian control (55). Time-restricted feeding aligns circadian rhythm of liver gene expression, acetylome, and glycogen and triglycerides stores to feeding times (35, 56, 57) and improves metabolic flexibility (25, 58). Our previous experiment with AgRP Crat KO mice showed differences in hepatic glycogen and triglyceride management after a single fast and revealed increased liver fatty acid oxidation resulting in impaired metabolic flexibility and nutrient partitioning, and increased fatty acid use (16). In the current study, after 25 days of time-restricted feeding, we found no genotype differences in liver triglycerides and glycogen, suggesting that circadian entrainment of liver metabolism enables appropriate adaptation in AgRP Crat KO mice. In support of this, KO mice have increased hepatic mRNA expression of lipogenic genes, which favors energy storage upon refeeding (59).

In summary, our results show that Crat in AgRP neurons assesses alterations in metabolic state, gauges food intake, and forms a critical component of an energy-calculating mechanism that allows an appropriate homeostatic response to restricted feeding. However, because KO mice commence feeding in a timeframe similar to that of WT mice without any deficit in FAA, we conclude that Crat deletion in AgRP neurons does not affect behavioral synchronization to altered food availability and is not likely to form a component of a FEO mechanism in AgRP neurons.

Acknowledgments

We thank Doug Compton from Research Diets for helping establish BioDAQ feeding cages.

Financial Support: This study was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Grant 1126724 and Fellowship 1084344 (to Z.B.A.). This work used the PBRC Transgenic Core, which is supported in part by Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (Grant 8P20GM103528) and the Nutrition Obesity Research Center (Grant 2P30-DK072476-11A1) from the National Institutes of Health. A.R. is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Author Contributions: A.R. and Z.B.A. conceived and designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. Z.B.A. supervised and coordinated the project. A.R., M.M., J.A.B., S.H.L., M.B.L., R.S., and Z.B.A. performed the experiments. R.L.M. provided the Crat floxed mouse model. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ACC2

acetyl–coenzyme A carboxylase β

- AgRP

agouti-related protein

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- CoA

coenzyme A

- Crat

carnitine acetyltransferase

- FAA

food anticipatory activity

- FEO

food-entrainable oscillator

- Gck

glucokinase

- KO

knockout

- NEFA

nonesterified fatty acid concentration

- WT

wild-type

- ZG

Zeitgeber time

References

- 1. Carneiro BT, Araujo JF. The food-entrainable oscillator: a network of interconnected brain structures entrained by humoral signals? Chronobiol Int. 2009;26(7):1273–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kosse C, Gonzalez A, Burdakov D. Predictive models of glucose control: roles for glucose-sensing neurones. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2015;213(1):7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andermann ML, Lowell BB. Toward a wiring diagram understanding of appetite control. Neuron. 2017; 95(4):757–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blum ID, Lamont EW, Rodrigues T, Abizaid A. Isolating neural correlates of the pacemaker for food anticipation. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Betley JN, Xu S, Cao ZFH, Gong R, Magnus CJ, Yu Y, Sternson SM. Neurons for hunger and thirst transmit a negative-valence teaching signal. Nature. 2015;521(7551):180–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen Y, Lin YC, Zimmerman CA, Essner RA, Knight ZA. Hunger neurons drive feeding through a sustained, positive reinforcement signal. eLife. 2016;5:e18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garfield AS, Shah BP, Burgess CR, Li MM, Li C, Steger JS, Madara JC, Campbell JN, Kroeger D, Scammell TE, Tannous BA, Myers MG Jr, Andermann ML, Krashes MJ, Lowell BB. Dynamic GABAergic afferent modulation of AgRP neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(12):1628–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beutler LR, Chen Y, Ahn JS, Lin YC, Essner RA, Knight ZA. Dynamics of gut-brain communication underlying hunger. Neuron. 2017;96(2):461–475.e465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Su Z, Alhadeff AL, Betley JN. Nutritive, post-ingestive signals are the primary regulators of AgRP neuron activity. Cell Reports. 2017;21(10):2724–2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krashes MJ, Koda S, Ye C, Rogan SC, Adams AC, Cusher DS, Maratos-Flier E, Roth BL, Lowell BB. Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1424–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burnett CJ, Krashes MJ. Resolving behavioral output via chemogenetic designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs. J Neurosci. 2016;36(36):9268–9282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tan K, Knight ZA, Friedman JM. Ablation of AgRP neurons impairs adaption to restricted feeding. Mol Metab. 2014;3(7):694–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koves TR, Ussher JR, Noland RC, Slentz D, Mosedale M, Ilkayeva O, Bain J, Stevens R, Dyck JR, Newgard CB, Lopaschuk GD, Muoio DM. Mitochondrial overload and incomplete fatty acid oxidation contribute to skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2008;7(1):45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muoio DM. Metabolic inflexibility: when mitochondrial indecision leads to metabolic gridlock. Cell. 2014;159(6):1253–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muoio DM, Noland RC, Kovalik JP, Seiler SE, Davies MN, DeBalsi KL, Ilkayeva OR, Stevens RD, Kheterpal I, Zhang J, Covington JD, Bajpeyi S, Ravussin E, Kraus W, Koves TR, Mynatt RL. Muscle-specific deletion of carnitine acetyltransferase compromises glucose tolerance and metabolic flexibility. Cell Metab. 2012;15(5):764–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reichenbach A, Stark R, Mequinion M, Denis RRG, Goularte JF, Clarke RE, Lockie SH, Lemus MB, Kowalski GM, Bruce CR, Huang C, Schittenhelm RB, Mynatt RL, Oldfield BJ, Watt MJ, Luquet S, Andrews ZB. AgRP neurons require carnitine acetyltransferase (CRAT) to regulate metabolic flexibility and peripheral nutrient partitioning. Cell Reports. 2018;22(7):1745–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buijs FN, Guzman-Ruiz M, Leon-Mercado L, Basualdo MC, Escobar C, Kalsbeek A, Buijs RM. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0028-17.2017. Suprachiasmatic nucleus interaction with the arcuate nucleus; essential for organizing physiological rhythms. eNeuro. 2017;4(2):ENEURO.0028-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Girardet C, Mavrikaki M, Southern MR, Smith RG, Butler AA. Assessing interactions between Ghsr and Mc3r reveals a role for AgRP in the expression of food anticipatory activity in male mice. Endocrinology. 2014;155(12):4843–4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Begriche K, Marston OJ, Rossi J, Burke LK, McDonald P, Heisler LK, Butler AA. Melanocortin-3 receptors are involved in adaptation to restricted feeding. Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11(3):291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burdakov D, Luckman SM, Verkhratsky A. Glucose-sensing neurons of the hypothalamus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360(1464):2227–2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levin BE, Becker TC, Eiki J, Zhang BB, Dunn-Meynell AA. Ventromedial hypothalamic glucokinase is an important mediator of the counterregulatory response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Diabetes. 2008;57(5):1371–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kang L, Dunn-Meynell AA, Routh VH, Gaspers LD, Nagata Y, Nishimura T, Eiki J, Zhang BB, Levin BE. Glucokinase is a critical regulator of ventromedial hypothalamic neuronal glucosensing. Diabetes. 2006;55(2):412–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dunn-Meynell AA, Routh VH, Kang L, Gaspers L, Levin BE. Glucokinase is the likely mediator of glucosensing in both glucose-excited and glucose-inhibited central neurons. Diabetes. 2002;51(7):2056–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lynch RM, Tompkins LS, Brooks HL, Dunn-Meynell AA, Levin BE. Localization of glucokinase gene expression in the rat brain. Diabetes. 2000;49(5):693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bray MS, Ratcliffe WF, Grenett MH, Brewer RA, Gamble KL, Young ME. Quantitative analysis of light-phase restricted feeding reveals metabolic dyssynchrony in mice. Int J Obes. 2013;37(6):843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Verhagen LA, Luijendijk MC, de Groot JW, van Dommelen LP, Klimstra AG, Adan RA, Roeling TA. Anticipation of meals during restricted feeding increases activity in the hypothalamus in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34(9):1485–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, Peek CB, Affinati A, Maury E, Bass J. Circadian clocks and metabolism. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013;217:127–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Girotti M, Weinberg MS, Spencer RL. Diurnal expression of functional and clock-related genes throughout the rat HPA axis: system-wide shifts in response to a restricted feeding schedule. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296(4):E888–E897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wiater MF, Mukherjee S, Li AJ, Dinh TT, Rooney EM, Simasko SM, Ritter S. Circadian integration of sleep-wake and feeding requires NPY receptor-expressing neurons in the mediobasal hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301(5):R1569–R1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oosterman JE, Kalsbeek A, la Fleur SE, Belsham DD. Impact of nutrients on circadian rhythmicity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308(5):R337–R350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yasumoto Y, Hashimoto C, Nakao R, Yamazaki H, Hiroyama H, Nemoto T, Yamamoto S, Sakurai M, Oike H, Wada N, Yoshida-Noro C, Oishi K. Short-term feeding at the wrong time is sufficient to desynchronize peripheral clocks and induce obesity with hyperphagia, physical inactivity and metabolic disorders in mice. Metabolism. 2016;65(5):714–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. de Vasconcelos AP, Bartol-Munier I, Feillet CA, Gourmelen S, Pevet P, Challet E. Modifications of local cerebral glucose utilization during circadian food-anticipatory activity. Neuroscience. 2006;139(2):741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patton DF, Katsuyama AM, Pavlovski I, Michalik M, Patterson Z, Parfyonov M, Smit AN, Marchant EG, Chung SH, Abizaid A, Storch KF, de la Iglesia H, Mistlberger RE. Circadian mechanisms of food anticipatory rhythms in rats fed once or twice daily: clock gene and endocrine correlates [published correction appears in PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0120223]. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e112451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rastogi A, Mintz EM. Neural correlates of food anticipatory activity in mice subjected to once- or twice-daily feeding periods. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;46(7):2265–2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shamsi NA, Salkeld MD, Rattanatray L, Voultsios A, Varcoe TJ, Boden MJ, Kennaway DJ. Metabolic consequences of timed feeding in mice. Physiol Behav. 2014;128:188–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lo MT, Chiang WY, Hsieh WH, Escobar C, Buijs RM, Hu K. Interactive effects of dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus and time-restricted feeding on fractal motor activity regulation. Front Physiol. 2016;7:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Patton DF, Mistlberger RE. Circadian adaptations to meal timing: neuroendocrine mechanisms. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Merkestein M, van Gestel MA, van der Zwaal EM, Brans MA, Luijendijk MC, van Rozen AJ, Hendriks J, Garner KM, Boender AJ, Pandit R, Adan R. GHS-R1a signaling in the DMH and VMH contributes to food anticipatory activity. Int J Obes. 2014;38(4):610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chavan R, Feillet C, Costa SS, Delorme JE, Okabe T, Ripperger JA, Albrecht U. Liver-derived ketone bodies are necessary for food anticipation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wortley KE, Anderson KD, Garcia K, Murray JD, Malinova L, Liu R, Moncrieffe M, Thabet K, Cox HJ, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ, Sleeman MW. Genetic deletion of ghrelin does not decrease food intake but influences metabolic fuel preference. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(21):8227–8232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wiater MF, Li AJ, Dinh TT, Jansen HT, Ritter S. Leptin-sensitive neurons in the arcuate nucleus integrate activity and temperature circadian rhythms and anticipatory responses to food restriction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305(8):R949–R960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Namvar S, Gyte A, Denn M, Leighton B, Piggins HD. Dietary fat and corticosterone levels are contributing factors to meal anticipation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016;310(8):R711–R723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stephan FK, Davidson AJ. Glucose, but not fat, phase shifts the feeding-entrained circadian clock. Physiol Behav. 1998;65(2):277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Escobar C, Díaz-Muñoz M, Encinas F, Aguilar-Roblero R. Persistence of metabolic rhythmicity during fasting and its entrainment by restricted feeding schedules in rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(5 Pt 2):R1309–R1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lockie SH, Andrews ZB. The hormonal signature of energy deficit: Increasing the value of food reward. Mol Metab. 2013;2(4):329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mitchell SE, Delville C, Konstantopedos P, Derous D, Green CL, Wang Y, Han JD, Promislow DE, Douglas A, Chen L, Lusseau D, Speakman JR. The effects of graded levels of calorie restriction: V. Impact of short term calorie and protein restriction on physical activity in the C57BL/6 mouse. Oncotarget. 2016;7(15):19147–19170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gallardo CM, Hsu CT, Gunapala KM, Parfyonov M, Chang CH, Mistlberger RE, Steele AD. Behavioral and neural correlates of acute and scheduled hunger in C57BL/6 mice. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e95990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vaanholt LM, Mitchell SE, Sinclair RE, Speakman JR. Mice that are resistant to diet-induced weight loss have greater food anticipatory activity and altered melanocortin-3 receptor (MC3R) and dopamine receptor 2 (D2) gene expression. Horm Behav. 2015;73:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Akashi M, Hayasaka N, Yamazaki S, Node K. Mitogen-activated protein kinase is a functional component of the autonomous circadian system in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2008;28(18):4619–4623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goldsmith CS, Bell-Pedersen D. Diverse roles for MAPK signaling in circadian clocks. Adv Genet. 2013;84:1–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Delezie J, Dumont S, Sandu C, Reibel S, Pevet P, Challet E. Rev-erbα in the brain is essential for circadian food entrainment. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):29386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yoshihara T, Honma S, Honma K. Effects of restricted daily feeding on neuropeptide Y release in the rat paraventricular nucleus. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(4 Pt 1):E589–E595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Redman LM, Martin CK, Williamson DA, Ravussin E. Effect of caloric restriction in non-obese humans on physiological, psychological and behavioral outcomes. Physiol Behav. 2008;94(5):643–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Soare A, Cangemi R, Omodei D, Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Long-term calorie restriction, but not endurance exercise, lowers core body temperature in humans. Aging (Albany NY). 2011;3(4):374–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krishnaiah SY, Wu G, Altman BJ, Growe J, Rhoades SD, Coldren F, Venkataraman A, Olarerin-George AO, Francey LJ, Mukherjee S, Girish S, Selby CP, Cal S, Er U, Sianati B, Sengupta A, Anafi RC, Kavakli IH, Sancar A, Baur JA, Dang CV, Hogenesch JB, Weljie AM. Clock regulation of metabolites reveals coupling between transcription and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2017;25:961–974.e964.

- 56. Mauvoisin D, Atger F, Dayon L, Nunez Galindo A, Wang J, Martin E, Da Silva L, Montoliu I, Collino S, Martin FP, Ratajczak J, Canto C, Kussmann M, Naef F, Gachon F. Circadian and feeding rhythms orchestrate the diurnal liver acetylome. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1729–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57. Díaz-Muñoz M, Vázquez-Martínez O, Báez-Ruiz A, Martínez-Cabrera G, Soto-Abraham MV, Avila-Casado MC, Larriva-Sahd J. Daytime food restriction alters liver glycogen, triacylglycerols, and cell size. A histochemical, morphometric, and ultrastructural study. Comp Hepatol. 2010;9(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, DiTacchio L, Bushong EA, Gill S, Leblanc M, Chaix A, Joens M, Fitzpatrick JA, Ellisman MH, Panda S. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2012;15(6):848–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bruss MD, Khambatta CF, Ruby MA, Aggarwal I, Hellerstein MK. Calorie restriction increases fatty acid synthesis and whole body fat oxidation rates. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298(1):E108–E116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]