Abstract

Background:

Rural health disparities are well-documented. “New destination” communities in predominantly rural states have emerged in recent years, with immigrants moving into these communities for better opportunities. Few reports of community-based participatory partnerships with these communities have been previously described in the literature.

Objectives:

We report on the formation and implementation of a community–academic partnership to reduce health disparities in a rural Midwestern community.

Methods:

We describe the creation of a partnership between the University of Iowa (UI) Prevention Research Center (PRC) and the Ottumwa, Iowa community.

Results:

We describe the partnership formation, activities, and results of the implementation of the partnership, and challenges encountered, including balancing attention to different health disparities populations and ensuring mechanisms for hearing from the different voices in the community.

Conclusions:

Our experience suggests the importance and challenge of considering the multiple dimensions of health disparities in rural new destination Midwestern communities.

Keywords: Rural health, Latino health, health disparities, CBPR, new destination

Health disparities in rural communities are well documented, with risk factors and outcomes such as obesity, heart disease, and premature mortality higher among rural residents.1,2 Rural health disparities have been the topic of increasing attention, given recent evidence that rural–urban disparities may be widening for some outcomes.3,4 Another important and overlooked aspect of rural health disparities is racial/ethnic and immigration-related diversity within rural communities. Many communities in predominantly rural states such as Iowa are “new destination” communities for immigrants, particularly Latino immigrants, from traditional receiving communities in the United States who move to new, often rural, communities in search of better economic and social opportunities and stability.5

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is recognized as a research approach to address health disparities in communities.6,7 A central principle of CBPR is that the community is recognized as the unit of identity, with the understanding that a community’s identity may not map onto a defined geographic neighborhood or location and may be a geographically dispersed ethnic group with a sense of community identity and shared fate.8 Inherent in this principle is a focus on smaller units of identity within a community, which may encourage focusing on a smaller segment of a community and discourage a more community-wide approach. Projects that attempt a community-wide intervention using a CBPR approach may experience different challenges when implementing their partnership and intervention.

OBJECTIVES

We report here on the development and implementation of a community–academic partnership in a Midwestern rural community, and initial lessons learned from our attempt to implement a community-wide intervention to increase physical activity. The partnership uses a CBPR approach8,9 in which community partners and university faculty are involved as partners in all aspects of the research, from identifying the initial focus of the research, to making decisions about research design and serving as active partners in dissemination activities.

METHODS

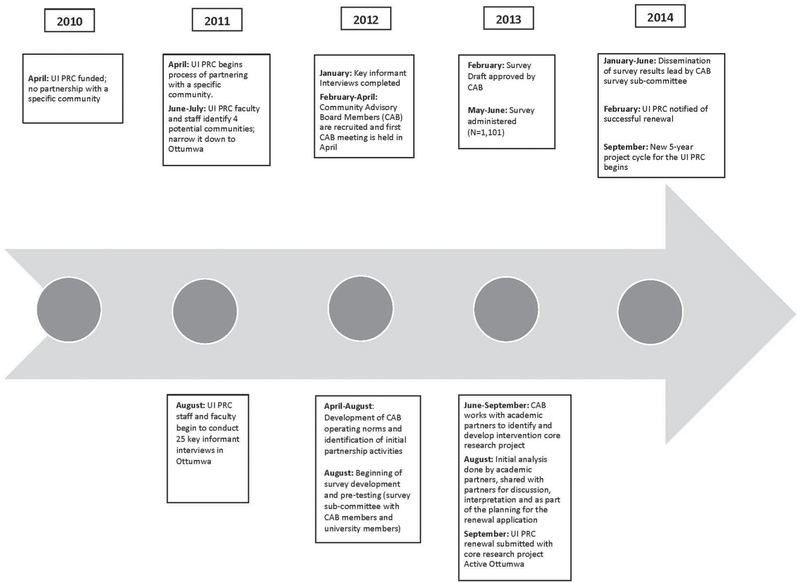

Below we describe our partnership formation (see Figure 1 for a timeline of the partnership formation and implementation of activities) All research activities have been approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Timeline of Partnership Formation and Implementation Activities

Formation of the Partnership

To guide the process of identifying potential communities with which to partner, UI PRC faculty and staff developed identification and selection criteria reflecting Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) priorities and characteristics of the communities. The criteria focus on the potential benefit of a partnership to the community (e.g., the presence of a health disparity in the community; evidence of health needs) as well as potential resources to draw upon (e.g., ongoing activities addressing community health; potential agencies/ organizations interested in participating in the partnership). We identified four potential communities. Two of the four had current university research projects being conducted in the community, and were eliminated from consideration owing to both concerns of overburdening the community and a desire to share academic resources throughout the state. UI PRC staff and investigators conducted initial key informant meetings with local health department staff in two other communities. From these initial meetings and a review of the data, we identified one community, Ottumwa, Iowa, as meeting many of the criteria. UI PRC investigators and staff then began a more extensive key informant interview process in this community.

During a 6-month period, UI PRC investigators and staff conducted 25 key informant interviews in Ottumwa, representing 18 organizations (e.g., local public health department, school district, hospital, community health clinic, churches, and city government). We identified interviewees through snowball sampling, asking each interviewee for suggestions of additional people to interview. Interviews followed a semistructured interview format with questions ranging from “Tell me what your organization does” to inquiring about Ottumwa’s primary strengths and challenges.

Description of Ottumwa

Ottumwa is the county seat of Wapello County, located 100 miles southwest of the University of Iowa. The city has a population of 24,487 people,10 making it a micropolitan community. Micropolitan areas are a relatively new classification of nonmetropolitan areas developed in 2003 by the U.S. Census Bureau and are defined as communities centered around a population core of 10,000 to 50,000 people.11 Ottumwa suffers from high rates of poverty (20.5%), compared with Iowa and the United States (12.3%, and 15.1% respectively).12

The area also has worse health outcomes compared with the rest of the state: Wapello County has higher health risk factors and poorer health compared with Iowa as a whole, with substantially higher risk of premature death, obesity, and physical inactivity. Wapello County ranked 97 out of Iowa’s 99 counties for health outcomes in 2017.13 Ottumwa has become a new destination location for many immigrants, including Latinos, who have moved to Ottumwa from other countries or other U.S. states. Sociodemographic changes in the city have been pronounced and rapid. In 1990, Ottumwa had fewer than 200 Latinos. In the intervening years, Ottumwa’s Latino population has grown to 3,401 and now makes up 13.8% of the town’s population.12

The previously mentioned key informant interviewees identified the following health issues in Ottumwa: lack of access to primary care, obesity, diabetes, substance abuse and mental health concerns. They also identified the following strengths and resources: the presence of many parks and an extensive trails system, a YMCA, downtown revitalization projects, a Federally Qualified Health Center, Iowa State University extension (particularly their work with Latino businesses), and a desire by city leadership, local schools, agencies, businesses, and churches to provide outreach and services to the growing Latino community.

Description of Partners and Who They Represent

The community–academic partnership in Ottumwa began in 2012 with the establishment of a community advisory board (CAB) and the commitment of university partners to establish a long-term partnership with the community, regardless of funding. The CAB is organizationally based, with community-based agencies and organizations designating a staff member to represent the organization on the CAB.14 Each organization in the partnership, including the university, has one vote on issues, but we strive to work by consensus instead of by majority voting rules.

Based on the information gathered in key informant interviews, university partners invited 13 organizations to join the CAB. The organizations were chosen owing to their organizational mission related to addressing health and/ or social determinants of health, populations served, and other attributes such as knowledge of the community and past successful participation in community partnerships.15 Representatives of the organizations also represented some of the ethnic diversity of the community, with three representatives of Latino ethnicity on the board. Representatives of ten organizations joined our CAB, including the school system, community college, United Way agency, community economic development action agency, a Federally Qualified Health Center, the YMCA, a local bank, the City Parks Department, Extension Agency, and the County Health department. Three additional organizations expressed interest in the work of the partnership. Two did not join the CAB owing to a lack of staff time to commit to the project. The third organization, a local church with many Latino parishioners and social service programs for newly arrived Latino community members, initially joined the CAB but later resigned owing to constraints on staff time. The CAB meets monthly for 2 hours and CAB organizations receive a $1,500 stipend to compensate them for their staff’s involvement.

In the first three months after we came together as a CAB, in accordance with recommended CBPR procedures to ensure power sharing and shared decision-making, we developed a set of operating norms to guide the partnership.16 CAB meetings were initially facilitated by UI academic members until community chairs from the CAB could be elected. In the initial meetings, University partners introduced the CDC PRC national structure and its goals, and the concepts of applied public health research and CBPR. We shared examples of other CBPR projects that might be relevant to our partnership, as well as examples of how other partnerships had developed bylaws and/or operating principles.14,16,17 In August 2012, the CAB approved a set of operating norms/principles.

These early meetings also included a discussion of the focus of the partnership, including review of health topics generated in the key informant interviews, available data on the city of Ottumwa, and discussion of who and what should be the focus of the intervention activities. For example, in our first CAB meeting, university partners raised the issue of what populations to focus on in the community and whether to focus solely on the Latino population, given the national goal of PRCs to focus on health disparity populations. In the ensuing discussion, CAB members suggested implementing a community-wide approach, noting that rural health disparities potentially impact all members of the community and that many of the same health issues affecting the Latino population also affect the larger Caucasian population. At the same time, they also acknowledged that intervention activities would need to include culturally appropriate methods for Latino participants and potentially address different social determinants of health.

Since its inception, the CAB has guided the actions of the partnership. The partnership has undertaken a community health survey, identified areas for intervention programming (including implementation of investigator-initiated pilot grants), and completed a successful renewal proposal to a 5-year CDC PRC program for a community-wide physical activity intervention.

RESULTS

Community Health Survey

As our first major activity, we undertook a community health survey to better identify health issues for potential interventions. University representatives introduced the idea of a community survey as a potential activity, if the CAB thought there was a need for greater community-specific data on health and social determinants. Some members of the CAB expressed doubt that a survey was needed, noting that several agencies had already done surveys, and suggested working with these agencies to use the survey data already collected. Others noted that a new survey could include information about behavior and other information relevant to health not included in previous agency surveys. Further, previous surveys were not conducted in Spanish to reach the Latino community, and the results of these surveys were not widely shared with other agencies and the community. University partners also noted that previous surveys seemed to be mostly convenience samples, which would not be generalizable to the community. The CAB decided to proceed with a survey and form a survey subcommittee to work on all aspects of the survey development.

A survey subcommittee was formed and composed of three community representatives, two academic members and one staff member. They met biweekly to discuss all details of the survey and review potential items and drafts. The sub-committee initially discussed having a door-to-door survey, but when the university partners calculated the estimated costs, that option was too expensive for available funds so the group recommended undertaking a phone survey instead. The subcommittee also developed initial drafts of the survey instrument, after the overall CAB identified broad areas and topics for inclusion. The academic members of the subcommittee brought constructs and related validated questionnaire items relevant to the identified topics to the subcommittee for review.

The subcommittee’s input helped to shape the questionnaire. For example, they suggested adding items to unfair treatment questions that would include “living in a certain neighborhood” as a reason why one might experience unfair treatment and also suggested items relating to observed drug use, crime in one’s neighborhood, and access to oral health care. During CAB monthly meetings, the survey subcommittee presented their work for discussion. The CAB approved and finalized the 89-item survey questionnaire and survey protocol (e.g., incentives; sampling frame of only residents in the city limits of Ottumwa; use of a telephone survey; all informational materials describing the survey and its purpose). The survey began in May 2013 and continued through August with more than 1000 surveys completed.

An important additional component to the survey was the dissemination of results to the wider community. CAB members had emphasized that wider dissemination was needed, noting that previous agency survey results had not been shared. The survey subcommittee drafted a 35-page booklet describing the results of the survey through graphs and charts and including comparative information at the state and/or national level, when available. This booklet was sent to survey respondents who requested it, as well as to community organizations and agencies. The CAB also held a major community forum to present the results of the survey, with CAB and university members co-presenting the results at two different community venues to different organizations and community groups.

Intervention Planning and Grant Submission

In late 2012, the university partners shared with the CAB that the renewal Funding Opportunity Announcement for the PRCs would be released in summer of 2013. The partners began discussing the focus for the required core research project. The university partners shared that CDC was emphasizing projects focused on their identified “winnable battles”18 and using interventions from “The Guide to Community Preventive Services” (Community Guide).19 The CAB also discussed using the community survey data to guide the focus of the intervention. Although the CAB discussed its preference to focus on mental health issues, this topic was not one emphasized in the winnable battles. The group had a discussion about whether that would impact the chances for the UI PRC to be refunded.

The CAB held two 1-day retreats to allow time for in-depth planning of the PRC renewal activities and grant proposal. During the first retreat, university partners prepared handouts on the results of the survey and potential priority areas based on these results. After a review of the materials, data, and discussions, the CAB decided to focus on increasing physical activity as the goal of the core research project, as it would be beneficial to both reducing obesity and improving mental health, leverage existing resources in the community, and address a disparity present in both rural and Latino populations, obesity.

In the second retreat, university partners prepared and shared information on possible evidence-based interventions from the Community Guide and other sources. After reviewing possible intervention strategies from the Community Guide, the CAB decided to use a lay health advisor (LHA) strategy to promote physical activity. This intervention strategy would allow for the development of human capacity and capital, leverage resources and assets already available in the community, and provide opportunities to target the diverse units of identity existing in the city, thus allowing for a community-wide intervention that was community-based instead of “community-placed.” The core research project was named “Active Ottumwa.”

The project is now in its fifth year and the CAB continues to provide guidance for the implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of Active Ottumwa, including reviewing and approving all data collection instruments and protocols, participating in the selection process of LHAs, approving all intervention protocols, interpreting evaluation results, and participating as partners and co-authors in all dissemination activities. In addition, the CAB members have been instrumental in disseminating awareness of the Active Ottumwa intervention, suggesting strategies for social media and approving all materials for mass media campaigns that have been undertaken.

We have retained all of the original CAB member organizations, although some of the organizational representatives have changed through the six years of the partnership (note: one organization we added after the inception of the CAB subsequently resigned owing to a lack of staff time). The CAB discussed a process for adding new members and noted the need to keep the group a manageable working size, and ensure new members fit with the work and mission of the PRC. Results from our annual CAB evaluation survey, in which CAB members responded anonymously to questions about their general satisfaction with the partnership and its impact, suggest high satisfaction with the partnership (Table 1).

Table 1.

Annual Responses to Anonymous Community Advisory Board Evaluation Survey

| Year |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 (n = 8), % | 2016 (n = 7), % | 2017 (n = 8), % | |

| I am generally satisfied with the activities and progress of Active Ottumwa during the past year. | |||

| Strongly disagree | — | — | — |

| Disagree | — | — | — |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 12.5 | — | — |

| Agree | 75.0 | 71.4 | 50.0 |

| Strongly agree | 12.5 | 28.6 | 50.0 |

| I have a sense of ownership in what Active Ottumwa does and accomplishes. | |||

| Strongly disagree | — | — | — |

| Disagree | — | — | — |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 25.0 | — | — |

| Agree | 50.0 | 71.4 | 50.0 |

| Strongly agree | 25.0 | 28.6 | 37.5 |

| The UI PRC has a positive effect on the community | |||

| Strongly disagree | — | — | — |

| Disagree | 12.5 | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 25.0 | 14.3 | 42.9 |

| Agree | 25.0 | 57.1 | 57.1 |

| Strongly agree | 37.5 | 28.6 | |

| Community interests are well represented on Active Ottumwa. | |||

| Strongly disagree | — | — | — |

| Disagree | — | — | — |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 12.5 | 16.7 | 62.5 |

| Agree | 75.0 | 50.0 | 37.5 |

| Strongly agree | 12.5 | 33.3 | |

| The UI PRC has been effective about informing policymakers and key government officials about Active Ottumwa. | |||

| Strongly disagree | 12.5 | — | — |

| Disagree | 37.5 | 14.3 | 25.0 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 50.0 | 42.9 | 62.5 |

| Agree | — | 42.9 | 12.5 |

| Strongly agree | — | — | |

| I am comfortable discussing problems and issues with the Center Coordinator and/or the CAB Co-Chairs to bring to the attention of the Director of the UI PRC. | |||

| Strongly disagree | — | — | — |

| Disagree | 12.5 | — | — |

| Neither agree nor disagree | — | — | — |

| Agree | 50.0 | 71.4 | 62.5 |

| Strongly agree | 37.5 | 28.6 | 37.5 |

CAB = community advisory board

UI PRC = University of Iowa Prevention Research Center

The results of the evaluation data are discussed at the annual CAB retreat and, where necessary, changes to the operation of the partnership have been implemented. For example, researchers brought up to the CAB the idea of paying LHAs for conducting physical activities to increase the number of activities in the community. During this discussion, the CAB felt strongly that was not model they wanted to implement in the community and was not going to be sustainable. Other strategies were discussed to increase the number of LHAs and activities, which were implemented and have been successful. In this article, we highlight some of our partnership challenges.

Balancing Attention to Different Health Disparities Populations

As noted, one of the earliest conversations between the CAB and university partnership members was around whether to focus solely on Latino populations or broaden the focus to the entire community. About 1 year after this conversation, when the CAB began planning the core intervention project for the renewal proposal, discussions included the specific social determinants of health that might be faced by Ottumwa’s growing Latino population. Although the academic partners (two of whom were Latino) had not proposed focusing solely on the Latino population, after a planning meeting one academic partner (who was Caucasian and the center principal investigator) received a call from a Caucasian CAB member suggesting that she and another CAB member worried that a focus on Latino partners only would not be well-supported by the community, owing to the feeling that the need for health interventions and assistance in improving the health of the community included many community members suffering from rural health disparities, in addition to Latinos.

To address this point of tension, researchers first reached out to the CAB chair for discussion and advice. At the advice of the chair, the researchers initiated an honest and transparent conversation with the CAB members who were concerned and subsequently addressed the issue with the entire CAB at the next CAB meeting. During this meeting, the academic partner clarified that it was never the intent of the intervention, but that the university researchers wanted to be inclusive of the needs of the total population of the city, which is why they kept bringing up issues relevant to the Latino population of the community.

This point was important in the evolution of the partnership, because it represented the first conversation of a challenging nature and set the parameters for subsequent conversations of a similar nature, such as conversations around low attendance and participation by one of the community partners and how to address that. One outcome from these conversations was the approval by the CAB of two pilot grants which focused on Latino populations in Ottumwa: a photovoice project focused on Latino men and mental health, and a healthy food access project focused on Latino small grocery stores. Both of these projects were funded only after approval from the CAB.

Challenge of Ensuring Mechanisms for Hearing from the Different Voices in the Community

As Stoecker notes,20 aspects of CBPR may play out differently in new or less established communities, and leaders may not have emerged in these communities. Others have noted the challenges in attempting CBPR in new destination communities,21 including ensuring representation of residents who have newly arrived in the community, working with marginalized populations that might not be documented, and identifying leaders and organizations to best represent the community’s interests. The decision of the principal investigator of the project (E.A.P.) to choose an organizational-based model when initiating the partnership perhaps increased the challenges. One CAB member raised this issue in the second year of the project, asking how the partnership could truly involve the community, because the CAB was mostly service agencies and not community-based organizations.

In the ensuing discussion, suggestions made by CAB members included adding church representatives as a strategy, conducting community discussions in other venues, and beginning new projects such as the pilot project involving photovoice to yield more community-level representation. Additional strategies have included hiring more staff who are Latino and seeking and cultivating relationships with Latino community members to serve as informal advisors. Yet these suggestions have not fully resolved the issue and this aspect remains a challenge for the partnership. For example, the partnership has reached out to churches about CAB membership, including the church most active with the Latino community, but have had limited response, owing to concerns over time constraints for their staff. These churches have agreed to work with Active Ottumwa on a more informal basis.

CONCLUSIONS

As the UI PRC partnership and Active Ottumwa intervention project progresses, we are continuing to identify and engage different units of identity in the community and recruit LHAs from those communities. A community-wide approach has presented challenges in terms of the resources and understanding needed to implement the project while ensuring equitable representation among the different units of identity in the community. The recent focus on the health of rural Americans,22 especially in heartland communities such as Ottumwa, suggests that a focus on health equity is necessary and should consider multiple dimensions of diversity in rural America, and how context and lived experiences may also lead to disparities across racial and ethnic groups.23 Yet care must be taken to design a CBPR intervention that does not, as identified by Frohlich and Potvin,24 exacerbate health disparities in one or more populations, by taking a more population, community-wide approach to intervention design. Our expectation is that by taking a CBPR approach, our partnership can continue to develop a model that is inclusive of different community’s identities and experiences while reducing the disparities among all of them and of value to communities throughout the Midwest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 1 U48 DP005021–01 from the CDC. The findings and conclusions in this journal article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Research reported in this publication was additionally supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54TR001356. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eberhardt MS, Pamuk ER. The importance of place of residence: Examining health in rural and nonrural areas. Am J Public Health 2004. October;94(10):1682–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sparks PJ. Rural health disparities. International Handbook of Rural Demography 2012;3:255–71. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening rural-urban disparities in life expectancy, U.S., 1969–2009. Am J Prev Med 2014. February;46(2): e19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening rural-urban disparities in all-cause mortality and mortality from major causes of death in the USA, 1969–2009. J Urban Health 2014. April;91(2):272–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowley M, Lichter DT. Social disorganization in new Latino destinations? Rural Sociol 2010. December;74(4):573–604. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, Minkler M, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity 3rd ed. Hoboken (NJ): Jossey-Bass; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods for community-based participatory research for health 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998;19(1):173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Community-Campus Partnerships for Health. Community-based participatory research: Policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2001;14(2):182–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Census Bureau. Washington (DC): U.S. Census Bureau; 2016. [cited 2018 Feb 2]. QuickFacts: Ottumwa city, Iowa; [about 2 screens]. Available from: www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/ottumwacityiowa/PST045216 [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Census Bureau. Metropolitan and micropolitan 2018. [cited 2018 Feb 15]; Available from: www.census.gov/programs-surveys/metro-micro/about.html

- 12.U.S. Census Bureau. 2012–2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates 2018. [cited 2018 Jul 10]; Available from: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_16_5YR_DP05&src=pt

- 13.Remington PL, Catlin BB, Gennuso KP. The County Health Rankings: Rationale and methods. Popul Health Metr 2015; 13:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker EA, Israel BA, Williams M, Brakefield-Caldwell W, Lewis TC, Robins T, et al. Community action against asthma: Examining the partnership process of a community-based participatory research project. J Gen Intern Med 2003. July; 18(7):558–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duran B. Developing and maintaining partnerships with communities. In: Israel B, editor. Methods for community-based participatory research for health 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2013. p. 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker AB. Strategies and techniques for effective group process in CBPR partnerships. In: Israel BA, editor. Methods for community-based participatory research for health 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blumenthal DS. A community coalition board creates a set of values for community-based research. Prev Chronic Dis 2006. Jan;3(1):A16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Winnable battles 2018. [cited 2018 Jul 30]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/winnablebattles/

- 19.Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Guide to community preventive services [updated 2018; cited 2018 Jul 29]; Available from: www.thecommunityguide.org/

- 20.Stoecker R Are academics irrelevant? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. p. 107–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letiecq B S L Community-based participatory research with Mexican migrants in a new rural destination: A good fit? Action Research 2012;10(3):244–59. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erwin PC. Despair in the American heartland? A focus on rural health. Am J Public Health 2017. October;107(10):1533–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diez Roux AV. Despair as a cause of death: More complex than it first appears. Am J Public Health 2017. October;107(10):1566–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: The inequality paradox: The population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health 2008. February; 98(2):216–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]