Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is one of the most successful microbial pathogens, and currently infects over a quarter of the world's population. Mtb's success depends on the ability of the bacterium to sense and respond to dynamic and hostile environments within the host, including the ability to regulate bacterial metabolism and interactions with the host immune system. One of the ways Mtb senses and responds to conditions it faces during infection is through the concerted action of multiple cyclic nucleotide signaling pathways. This review will describe how Mtb uses cyclic AMP, cyclic di-AMP and cyclic di-GMP to regulate important physiological processes, and how these signaling pathways can be exploited for the development of novel thereapeutics and vaccines.

Keywords: signal transduction, cyclic nucleotides, gene regulation, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, host–pathogen interactions

Mycobacterium tuberculosis can use small molecules such as cyclic nucleotides in numerous ways to respond to changing environments and modulate host cell interactions during infection.

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of tuberculosis, is estimated to infect more than two billion people worldwide and is responsible for more deaths per year than any other microbial pathogen. The bacterium faces a dynamic and hostile environment during infection, including nutrient deprivation, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, low pH and hypoxia (Pieters and Gatfield 2002; Ehrt and Schnappinger 2009). Mtb's success as a pathogen relies on sensing and responding to these environmental conditions within the human host.

Signal transduction pathways enable cells to transmit and respond to signals from extracellular environments and between spatially separated intracellular domains. These pathways use cellular intermediaries to ensure that information is relayed to the appropriate targets. Small molecule secondary messengers, including cyclic nucleotides (cNTs), guanosine pentaphopshate ((p)pGpp), calcium ions (Ca2+), inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol, provide molecular links between cellular receptors and downstream effectors (Springett, Kawasaki and Spriggs 2004; Romling 2008; Dalebroux et al.2010; Gomelsky 2011). Mtb uses multiple cNTs, including 3΄,5΄-cyclic-AMP (cAMP), cyclic-di-AMP (c-di-AMP) and cyclic-di-GMP (c-di-GMP), both to regulate its own physiology in a wide range of conditions and to disrupt host cell signaling during infection. This review will address recent advances towards understanding the roles of these important cNT second messengers for Mtb biology and their potential as targets for development of antibiotics and vaccines.

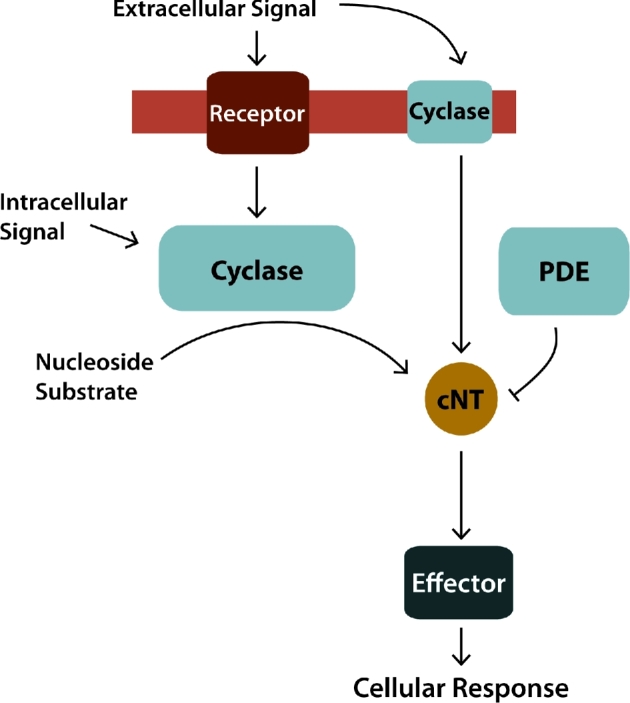

Despite considerable diversity among cNT signaling pathways, all share common core elements for conversion of environmental signals into cellular responses. For example, each pathway requires a sensor to detect environmental signals, a nucleotide cyclase to produce the cNT second messenger, a phosphodiesterase (PDE) to degrade the cNT and an effector molecule to respond to the cNT (Fig. 1). cNT cyclases are often post-translationally activated to produce signaling cNTs, allowing rapid responses to changing environmental conditions such as pH (Cann 2004). cNTs then bind and alter the functions of downstream proteins or regulatory RNAs that serve as effectors to generate a cellular response (Fig. 1). Despite this simple framework, cNT signaling networks can be quite complex, often involving the integration of multiple inputs, effectors and cellular responses.

Figure 1.

Cyclic nucleotide signaling pathway. Organisms from all domains of life use cyclic nucleotide (cNT) signaling pathways to coordinate cellular responses with extra and intracellular signals. (I) Nucleotide cyclases are either activated by an associated receptor or by directly sensing an environmental signal. (II) Once activated the cyclase converts a linear nucleotide substrate to the cNT second messenger, which can be degraded by phosphodiesterase (PDE) enzymes. (III) The cNT then interacts with downstream effectors, either proteins or regulatory RNAs, altering their function. (IV) This ultimately converts signals into cellular responses.

cAMP: a universal second messenger with complex roles in Mtb

cAMP was the first cNT to be discovered and it is known as the universal second messenger, because organisms from all domains of life use cAMP to regulate key cellular processes. Pioneering work by Earl Sutherland and colleagues demonstrated that mammalian tissues produce cAMP when treated with the extracellular hormone epinephrine (Rall and Sutherland 1958; Sutherland and Rall 1958). This discovery provided the first understanding of a mechanism by which cells use small molecules to couple extracellular signals, such as hormones, with intracellular processes. In the 60 years following its discovery, cAMP has been shown to regulate multiple cellular pathways in diverse organisms, including bacteria, fungi, protozoa and mammals.

cAMP signaling in mammals can occur when an extracellular ligand binds a surface exposed G-protein coupled receptor. This binding activates a cognate membrane-associated G protein in the cytoplasm which can then stimulate or inhibit the activity of an associated transmembrane (TM)-associated adenylyl cyclase (tmAC). A second group of soluble ACs, which are not associated with the plasma membrane, is directly regulated by bicarbonate and pH levels (reviewed by Tresguerres, Levin and Buck 2011). Direct stimulation of ACs by their chemical environment is a widely conserved phenomenon in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes, including Mtb, as discussed below (Braun and Dods 1975; Braun et al.1977; Chen et al.2000). Regardless of the activation mechanism, ACs convert ATP into the cAMP messenger, which then binds and activates downstream effector proteins, such as protein kinase A or Epac. The activation of these effectors ultimately determines the cellular response to the initial signal event.

The paradigm for cAMP signaling in prokaryotes as a modulator of gene expression stems from decades of research in E. coli focused on the role of cAMP in catabolite repression. In this case, cAMP signaling promotes the uptake and catabolism of alternative sugars in the absence of glucose. Under conditions where glucose is low, the sole AC, Cya, is activated to produce cAMP, which then binds the transcription factor (TF) cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP). cAMP binding allosterically increases CRP’s affinity for DNA, resulting in transcriptional regulation of genes encoding proteins required for the uptake and metabolism of alternative sugars, such as lactose (reviewed by Busby and Ebright 1999; Green et al.2014).

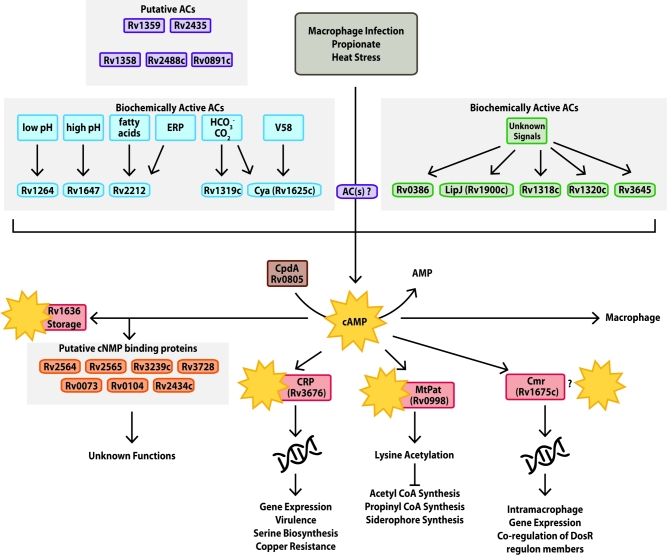

The Mtb genome encodes at least 15 putative class III AC genes (Cole et al.1998; McCue, McDonough and Lawrence 2000; Fleischmann et al.2002; Shenoy et al.2004), 10 of which have been purified and confirmed to be capable of converting ATP into cAMP (Fig. 2) (reviewed by Shenoy et al.2004; Shenoy and Visweswariah 2006; Agarwal and Bishai 2009; McDonough and Rodriguez 2011; Bai, Knapp and McDonough 2011; Knapp and McDonough 2014). Mtb ACs can be either membrane-associated (Rv1625c, Rv1318c, Rv1319c, Rv1320c, Rv3645, Rv2435c, Rv1358, Rv2488c) or cytoplasmic (Rv0891c, Rv1120c, Rv1264, Rv1647, Rv1359, Rv1900c, Rv2212) (reviewed by Shenoy et al.2004; Bai, Knapp and McDonough 2011; Knapp and McDonough 2014). All of the mycobacterial ACs are members of the diverse class III ACs, which include both prokaryotic and eukaryotic enzymes. Rv1625c and Rv2435 are phylogenetically grouped with eukaryotic tmACs (Reddy et al.2001), while the remaining ACs are associated with other prokaryotic ACs (McCue, McDonough and Lawrence 2000).

Figure 2.

cAMP signaling pathway in Mtb. cAMP signaling in Mtb is complex, involving up to 16 ACs, 10 of which have been biochemically shown to produce cAMP shown here. Rv1264, Rv1647, Rv2212, Rv1319c and Rv1625c are activated by known signals, including pH, fatty acids, protein-protein interactions and small molecules. The other five enzymes with confirmed AC activity have not been associated with specific signals. Mtb produces high levels of cAMP upon macrophage infection, growth on propionate or exposure to heat stress; however, the specific signals and ACs responsible are not known. Mtb can control the level of cAMP available in the cytoplasm by regulation of synthesis, hydrolysis via the Rv0805 PDE, secretion outside of the cell and by Rv1636 binding. There are 10 proteins with cNT-binding domains (CNBs), only Rv3676 (CRPMT), Rv1675c (Cmr) and Rv0998 (MtPat) have been characterized. CRPMT and Cmr are DNA-binding transcription factors (TF) that regulate mycobacterial gene expression, while MtPat is a lysine acetyl transferase that is activated by cAMP to inactivate downstream protein substrates.

The existence of so many different ACs allows Mtb to integrate multiple environmental stimuli with downstream cellular responses by using cAMP as a second messenger. Many of the mycobacterial cyclase domains are also fused to protein domains associated with other activities, including ATPase, helix-turn helix, HAMP (histidine kinases, ACs, methyl-binding proteins and phosphatases) or alpha-beta-hydrolase domains, which greatly enhances the functional potential of these cAMP signaling pathways (McCue, McDonough and Lawrence 2000; Shenoy et al.2004; McDonough and Rodriguez 2011; Bai, Knapp and McDonough 2011; Knapp and McDonough 2014). Despite the abundance of ACs, only one cAMP PDE (Rv0805) has been described in mycobacteria, and it is present only in pathogenic mycobacteria (Tyagi, Shenoy and Visweswariah 2009).

Multiple host-associated signals activate Mtb ACs

Many mycobacterial ACs sense and respond directly to chemical signals, and exposure of mycobacterial cultures to physiologically relevant conditions modulates their cAMP levels. For example, cAMP levels are 50 times higher in both Mtb and M. bovis BCG recovered from macrophages than in bacteria exposed to tissue culture media alone (Bai, Schaak and McDonough 2009). Mtb also elevates the production and secretion of cAMP when propionate is present in the medium (Johnson et al.2017), which is consistent with reports of cAMP-dependent regulation of enzymes involved in propionate metabolism (Nambi, Basu and Visweswariah 2010; Xu, Hegde and Blanchard 2011; Hayden et al.2013; Nambi et al.2013).

While heat shock, acid, starvation, nitrosative or oxidative stress can also increase cAMP levels, these effects are often small and variable (Gazdik et al.2009; Choudhary, Bishai and Agarwal 2014). One challenge in these studies is the difficulty of measuring transient and/or localized bursts of cAMP production in cell lysates. Therefore, much of what is known about the signals that affect cAMP production in Mtb is derived from enzymatic assays using individually purified recombinant ACs. Of the 10 biochemically characterized ACs, 5 have been associated with activating conditions, including pH (Rv1264, Rv1647), CO2/HCO3− (Rv1319c and Rv1625c) or fatty acids (Rv2212) (reviewed by Bai, Knapp and McDonough 2011; Knapp and McDonough 2014) (Fig. 2).

Relatively little is known about how most Mtb ACs are activated at the molecular level. The best characterized activation mechanism is the pH-mediated response of AC Rv1264. At pH 7.5, the N-terminal portion of the protein acts as an autoinhibitory regulatory domain. When exposed to low pH the regulatory domain rotates away from the catalytic domains, allowing Rv1264 to convert ATP to cAMP (Tews et al.2005). Rv1264 is 30-fold more active at pH 6.0 than at pH 7.5 (Tews et al.2005), while recombinant Rv1264 lacking the N-terminus is 300 times more active than intact Rv1264 in vitro (Linder, Schultz and Schultz 2002). A similar molecular switch is predicted to occur in other bacterial ACs, including the mycobacterial AC Rv2212, although regulation of Rv2212 activity is more complex than that of AC Rv1264 (Abdel Motaal et al.2006; Ganaie et al.2016).

AC Rv2212 is activated by pH and fatty acids (Abdel Motaal et al.2006), as well as by interaction with the mycobacterial virulence factor exported repetitive protein (Rv3810 or Erp) (Ganaie et al.2016). This interaction between Rv2212 and Erp was initially discovered by using a yeast two-hybrid assay baited with cytoplasmic Mtb Erp lacking a signal sequence (Mtb-ssΔErp). Co-precipitation of full-length Erp from Mtb lysates using anti-Rv2212 antibodies confirmed the interaction and showed that it requires the AC domain of Rv2212 (Ganaie et al.2016).

Addition of purified Mtb-ssΔErp increases cAMP production by recombinant Rv2212 in vitro, and expression of ssΔErp in H37Ra moderately increases cAMP production by live bacteria (Ganaie et al.2016). It is not known how Erp contributes to cAMP production by Rv2212, but Erp is not homologous with eukaryotic GCPRS, and the mechanism is likely novel. While the biological significance of the Rv2212-Erp interaction is unclear, the potential for protein–protein interactions as stimuli for activating mycobacterial ACs is intriguing and merits further study.

Another exciting recent development is the discovery of a small molecule inhibitor of Mtb, V-58, which directly and specifically activates AC Rv1625c (VanderVen et al.2015; Johnson et al.2017). Rv1625c functions as a membrane-associated homodimer in which each Rv1625c monomer is expected to contribute six TM domains and one catalytic site to resemble the characteristic architecture of mammalian tmACs (Guo et al.2001). Such tmACs contain 12 TM domains along with one true active site and one ‘pseudo-site’ on a single polypeptide chain (reviewed by Kamenetsky et al.2006). The plant diterpene forskolin binds the ‘pseudo-site’ of eukaryotic tmACs to allosterically stimulate synthesis of cAMP from the true active site (Barovsky, Pedone and Brooker 1984).

V-58 is proposed to fit into one of two putative active sites in the Rv1625c dimer, in a manner similar to that of forskolin (Johnson et al.2017). Forskolin is used routinely to study the impact of elevated cAMP on various aspects of cell physiology, and its discovery revolutionized the field of cAMP signaling in eukaryotic organisms (reviewed by Alasbahi and Melzig 2012). As the first small molecule found to rapidly stimulate robust cAMP production from a single AC in mycobacteria, V-58 has potential to be a powerful tool for studying cAMP signaling in Mtb.

A single PDE in Mtb, Rv0805, has multiple functions

The amount of cAMP present in a cell depends on the concerted regulation of its synthesis, degradation and secretion. Despite a multitude of ACs capable of generating cAMP, only one PDE (Rv0805) has been identified for cAMP degradation in Mtb. Rv0805 is a class III metallophosphoesterase and Rv0805 orthologs are encoded in the genomes of M. bovis, M. leprae and M. marinum, but not in M. smegmatis (Tyagi, Shenoy and Visweswariah 2009). A global mutagenesis screen identified Rv0805 as an essential gene for virulence in a murine CNS model of Mtb infection (Be et al.2008), suggesting a specific role for Rv0805 in some pathogenic mycobacteria. Purified Rv0805 hydrolyzes cAMP and cGMP to AMP and GMP respectively in vitro (Shenoy et al.2005, 2007; Keppetipola and Shuman 2008). However, Rv0805 has also biochemical and physiological characteristics that suggest it has functions beyond just the degradation of cAMP.

Rv0805 overexpression decreases cAMP levels by ∼30% in M. smegmatis and up to 50% in Mtb, but cAMP may not be Rv0805’s only substrate in vivo (Shenoy et al.2005; Agarwal et al.2009; Matange et al.2013). Purified Rv0805 hydrolyzes 2΄,3΄-cAMP 150 times more efficiently than 3΄,5΄-cAMP, due to a specific histidine residue in its active site (Keppetipola and Shuman 2008). The physiological significance of Rv0805’s 2΄,3΄-cAMP hydrolase activity merits further study, as 2΄,3΄-cAMP is linked to RNA degradation and metabolic toxicity in mice (reviewed by Jackson 2011). Several reports also indicate that Rv0805’s C-terminus is involved in transient interactions with the mycobacterial cell wall (Podobnik et al.2009; Matange, Podobnik and Visweswariah 2014). The physiological significance of this interaction remains unclear, although both mycobacterial cell wall permeability and gene expression may be affected by Rv0805’s localization (Podobnik et al.2009; Matange, Podobnik and Visweswariah 2014).

Regardless of Rv0805’s potential for multiple functions in Mtb, the absence of either an Rv0805 ortholog or alternative PDE from non-pathogenic mycobacteria such as M. smegmatis is puzzling. cAMP levels in M. smegmatis are comparable to those of Mtb, raising questions about how cAMP homeostasis is maintained in these organisms. Future work is needed to determine whether mycobacteria encode one or more cryptic PDEs, or if an alternate mechanism is used to reduce cAMP levels within the cell.

Effector proteins provide new paradigms for cAMP signaling in Mtb

cAMP is known for modulating gene expression, including virulence genes, via CRP/FNR family TFs such as CRP in many bacteria (reviewed by McDonough and Rodriguez 2011; Green et al.2014). However, cAMP signaling in Mtb may involve a far more diverse repertoire of downstream effector functions. Only 2 of 10 genes predicted to encode cAMP-binding effector proteins in Mtb have DNA-binding domains, and both of these (CRPMT (Rv3676), Cmr (Rv1675c)) are CRP/FNR family TFs. A third gene (Rv0998) encodes a lysine acetyl transferase (MtPat). Rv1636 has been identified as an atypical cAMP-binding protein, while seven putative cNMP-binding proteins are uncharacterized.

CRPMT is a virulence-associated global regulator

CRPMT is a global TF with a regulon of at least 100 genes, and crp-deficient strains of Mtb are attenuated for growth in culture medium, within macrophages and in murine infection models (Rickman et al.2005; Bai et al.2011). An in vitro growth defect of the Δcrp strain is due to reduced expression of the phosphoserine aminotransferase gene serC. Serine supplementation or overexpression of serC rescues growth of the Δcrp strain in liquid culture, but not in macrophages, indicating that CRPMT plays additional roles beyond the induction of serC expression during infection (Bai et al.2011).

Mtb virulence depends on the expression of the ESX-1 type VII secretion system (T7SS) (Lewis et al.2003), and loss of the region encoding ESX-1 genes, known as region of difference 1 (RD1), is a primary attenuating mutation in the M. bovis BCG vaccine strain (Pym et al.2002). ESX-1-mediated secretion is complex, and requires the co-secretion of multiple substrates, including gene products of the espACD-Rv3613c-Rv3612c operon (Rv3616c-Rv3612c) encoded outside the RD1 locus (Fortune et al.2005; MacGurn et al.2005; Chen et al.2012). Rv3616c-Rv3612c expression is increased in crp-deficient strains of Mtb grown in vitro, and there is a CRPMT-binding motif ∼1 kbp upstream of the espA start site (Rickman et al.2005). More work is required to determine the significance of CRPMT-mediated regulation of the espA operon during infection and whether CRPMT directly regulates expression of these crucial genes.

CRPMT also activates expression of the resuscitation promoting factor A gene (rpfA) (Rickman et al.2005), which encodes a growth factor capable of resuscitating growth of stationary phase mycobacterial cultures (Mukamolova et al.2002). The role for CRP during resuscitation has not been determined. CRPMT may also be needed for Mtb's adaptation to copper stress, as a BCG Δcrp strain was shown to be more sensitive to copper than wild-type BCG, and the highest affinity chromosomal-binding site for CRPMT is upstream of the putative copper transporter ctpB (Rv0103c) (Knapp et al.2015). However, functional connections between cAMP, CRPMT and copper resistance require further study.

In addition, CRPMT contributes to central metabolism by regulating expression of the Sdh1 succinate dehydrogenase operon (Rv0249c-Rv0247c) in BCG (Knapp et al.2015). CRPMT binds upstream of frdA (Rv1552), suggesting that it also regulates expression of the fumarate reductase encoded by frdABCD (Rv1552–Rv1555) (Bai et al.2007; Hartman et al.2014; Knapp et al.2015). A third succinate dehydrogenase/fumarate reductase complex in Mtb, Sdh2 (Rv3316–Rv3319), is not regulated by CRPMT. The Sdh1 operon is required for optimal growth of Mtb in vitro (Sassetti and Rubin 2003) as well as in a mouse infection model (Griffin et al.2011).

CRPMT directly regulates Sdh1 expression by binding to four unique CRPMT-binding sites that are located proximal to two promoters upstream of Rv0250c and Rv0249c (Knapp et al.2015). Promoter reporter fusions in BCG showed that CRPMT represses the Rv0250c promoter, while activating the Rv0249c promoter, and that regulation from either promoter requires intact CRPMT-binding sites (Knapp et al.2015). In addition, an intragenic-binding site within the Rv0250c ORF contributes to Rv0249c expression, indicating that CRPMT exhibits regulatory activity beyond classic intergenic binding upstream of target ORFs.

While CRPMT and its orthologs are well characterized as classical TFs, the possibility that CRPMT also contributes to chromosome reorganization is an active area of investigation. CRPMT binds ∼2000 sites in the Mtb genome, 83% of which occur within intragenic regions (Knapp et al.2015). Such extensive binding resembles that of nucleoid-associated proteins, and suggests that CRPMT regulates the global architecture of the mycobacterial chromosome, as has been proposed for other CRP family members (Grainger et al.2005; Picossi, Flores and Herrero 2014). In this regard, CRPMT is known to bend DNA (Bai, McCue and McDonough 2005), which can also alter the ability of other factors to interact to DNA proximal to CRP sites.

The overall paradigm for cAMP’s role in Mtb gene regulation also differs in some respects from that of Escherichia coli. For example, Mtb does not undergo catabolite repression. In addition, CRPMT is known to bind cAMP, but its DNA-binding activity is relatively independent of cAMP compared with CRP from E. coli, which requires cAMP to bind DNA. To date, CRPMT’s regulatory activity has only been shown to be directly dependent on cAMP for one gene, whiB1, despite other important parallels to E. coli CRP (Stapleton et al.2010).

Cmr is an atypical CRP/FNR family TF

Cmr was discovered as a regulator of gene expression under elevated cAMP conditions and during Mtb infection of macrophages, earning the name cAMP and macrophage regulator (Gazdik and McDonough 2005; Gazdik et al.2009). Recent work has confirmed that Cmr is a global regulator in Mtb and uncovered novel aspects of Cmr's DNA-binding activity and its co-regulation of the dormancy survival regulator (DosR) regulon (Ranganathan et al.2016, 2017; Smith et al.2017).

Cmr's DNA-binding profile within M. bovis BCG was determined using chromatin immunoprecipation sequencing (ChIP-seq), which identified Cmr binding at ∼200 distinct regions of the genome (Ranganathan et al.2016). In some cases, Cmr binds multiple sites within short stretches of DNA, particularly at loci proximal to genes in the DosR regulon. Cmr may co-regulate expression of the DosR regulon both by repressing expression of the activator DosR and by directly controlling the transcription of individual DosR regulon members. Sixteen of the top 17 genes that exhibited altered expression in a microarray analysis of an Mtb cmr knockout strain are DosR regulon members, including dosR (devR, Rv3133c) and Rv2623 (Smith et al.2017). Cmr binds these promoter sequences and may directly regulate expression of both genes (Ranganathan et al.2016; Smith et al.2017). The possibility that Cmr contributes to Mtb persistence by modulating expression of genes in the DosR regulon is an important question for future study.

Cmr is expressed at low levels due in part to its autorepressive activity, but the environmental conditions that control Cmr expression and activity are poorly understood (Ranganathan et al.2016; Smith et al.2017). DNA binding by purified Cmr is sensitive to the redox state of the protein, and oxidative conditions abrogate DNA binding by Cmr (Smith et al.2017). However, the biological significance of Cmr's redox sensitivity requires further investigation. Mtb has a robust capacity for maintaining a reductive intracellular environment due to the function of redox controlling factors such as mycothiol (Buchmeier et al.2003), but transient fluxes might affect Cmr activity.

Cmr and CRPMT recognize very similar DNA motifs, but their genomic DNA-binding profiles are distinct, with Cmr binding far fewer sites than CRPMT (Knapp et al.2015; Ranganathan et al.2016, 2017). A recent study found that nucleotides at positions 4 and 13 of the binding motif are discriminatory bases that distinguish between Cmr and CRPMT binding. Differences in the aa's that contact DNA in the DNA-binding helices of each protein, with substitution of Glu189 in CRPMT for Pro209 in Cmr, likely drive this binding specificity (Ranganathan et al.2017). Additional DNA contact regions outside of the DNA-binding helices and a cooperative DNA-binding mechanism also differentiate Cmr's DNA-binding interactions from those of CRPMT. The nature of this cooperativity is such that Cmr is proposed to dimerize on the DNA rather than prior to DNA binding, which differs from other CRP/FNR family proteins (Ranganathan et al.2017).

A crystal structure of Cmr also reveals several novel structural features not found in CRP or other CRP/FNR family proteins (Ranganathan et al.2017). One of these is an arginine loop (Argloop) consisting of Arg93–96 that likely makes additional contacts with DNA. Mutation of these arginines to alanine residues specifically disrupts Cmr's ability to bind to sites that lack either of the preferred discriminatory bases. However, loss of the Argloop does not affect binding to sites that contain both the 4G and 13C favored by Cmr. In addition, Cmr's N-terminus was disordered in the crystal structure, but purified Cmr lacking this region binds DNA with higher affinity than does full-length Cmr protein (Ranganathan et al.2017). This indicates that the N-terminus affects Cmr's DNA-binding properties, possibly as a regulator, which likely becomes ordered upon binding an unknown cofactor. Together, these findings support a model in which Cmr uses expanded DNA contacts that are not present in CRPMT to modulate its DNA-binding interactions.

Fitting with the complexity of cAMP signaling in Mtb, Cmr's relationship with cAMP is not straightforward. Unlike CRPMT which has been shown to bind cAMP in vitro (Bai, McCue and McDonough 2005), direct binding of Cmr to cAMP has not been observed. The cAMP-binding pocket in Cmr is occluded by an extended N terminal alpha helix that threads through the core of the protein (Ranganathan et al.2017). Loss of conserved residues which form the cAMP pocket in CRPMT is consistent with this occlusion (Reddy et al.2009; Smith et al.2017). These structural data indicate that either major rearrangements or a novel binding site, perhaps associated with the unstructured N terminus, is required for cAMP to interact directly with Cmr.

Despite the lack of evidence for direct cAMP-Cmr binding, biological observations are consistent with a regulatory interaction between these molecules. Cmr expression is required for cAMP-induced changes in the BCG proteome (Gazdik et al.2009) and the addition of cAMP alters the binding of Cmr proximal to DosR regulon members in vivo (Ranganathan et al.2016). cAMP also affects the mobility of some Cmr-DNA complexes in vitro, consistent with conformational changes. Cmr's role in Mtb's cAMP signaling is clearly more complex than initially predicted, and elucidation of the molecular connection between cAMP and Cmr is an important future research priority.

MtPat (Rv0998) is a novel cAMP-activated protein lysine acetyltransferase

In contrast to E. coli, which uses cAMP solely to modulate gene transcription, cAMP signaling in Mtb regulates key metabolic processes at multiple levels. For example, cAMP signaling in Mtb also post-translationally modulates Mtb metabolism via the cAMP-responsive protein lysine acetyltransferase, Rv0998 (MtPat, KATmt). Protein lysine acetylation controls essential cellular processes in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. While both cAMP signaling and protein acetylation are ubiquitous in nature, only mycobacteria are known to encode proteins that encode both cAMP binding and GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase (GNAT) domains in a single ORF (Nambi, Basu and Visweswariah 2010). GNAT activity of MtPat and the M. smegmatis ortholog MSMEG_5458 (MsPat) are directly regulated by cAMP binding, which is required for acetylase activity in vitro (Nambi, Basu and Visweswariah 2010; Xu, Hegde and Blanchard 2011). All sequenced mycobacterial genomes, including M. leprae, contain a homolog of MtPat (Nambi, Basu and Visweswariah 2010), emphasizing the importance of this regulatory function in mycobacteria.

Structural studies suggest that MtPat's activity is controlled by a ‘steric double latch’ regulatory mechanism (Lee et al.2012). In the absence of cAMP, MtPat adopts an autoinhibitory conformation, where the active site is occluded by both the regulatory cNMP-binding domain and a lid in the catalytic domain. cAMP binding induces dramatic conformational changes in MtPat, rotating the regulatory domain ∼40A° away from the catalytic site, and causing the inhibitory lid to refold. These rearrangements allow protein substrates to access the active site (Lee et al.2012).

Once activated by cAMP, MtPat transfers an acetyl group from acetyl-coA to specific lysine residues on its enzymatic targets to inactivate them. These enzymes can in turn be deacetlyted by Rv1151c, a sirtuin-like enzyme, restoring their enzymatic activities (Xu, Hegde and Blanchard 2011; Hayden et al.2013; Nambi et al.2013). cAMP, MtPat and Rv1151c form a complete protein acetylation pathway that is unique to mycobacteria. cAMP also regulates protein acetylation in enteric bacteria, such as E. coli, but in this case cAMP’s role is to increase transcription of the acetyltransferase gene patZ via cAMP-CRPEC (Castano-Cerezo et al.2011 reviewed by Knapp and McDonough 2014).

MtPat regulates several key metabolic enzymes in Mtb, as well as enzymes involved in siderophore and glycolipid synthesis. The best characterized substrate for MtPat is Rv3667, the acetyl-coA-synthase (ACS) and its homologs, which generate the important metabolite acetyl-coA (Xu, Hegde and Blanchard 2011; Hayden et al.2013; Nambi et al.2013; Noy, Xu and Blanchard 2014). ACS is also reported to serve as a propionyl-coA synthase, capable of converting propionate to propionyl-coA (Li et al.2011; Lee et al.2013). Propionyl-coA and its downstream metabolites are toxic to Mtb and mutants unable to detoxify propionyl-coA cannot grow in the presence of propionate (Munoz-Elias et al.2006; Upton and McKinney 2007; Savvi et al.2008). Loss of the cAMP-dependent PAT KATbcg attenuates the growth of M. bovis BCG on propionate (Nambi et al.2013), likely due to increased propionyl-coA synthesis by ACS in this strain. This is consistent with the finding that transposon disruption of the acs gene restores growth of an Δicl (Rv0467) mutant that is sensitive to propionate by preventing the accumulation of propionyl-coA (Lee et al.2013). In addition to acetylating its targets, MtPat can also use propionyl-coA as a substrate to propionylate ACS (Nambi et al.2013), indicating that cAMP and MtPat have a complex role in regulating mycobacterial metabolism.

As previously mentioned, Mtb grown on propionate produces and secretes over 10 times the amount of cAMP found in Mtb grown on glycerol as the primary carbon source (Johnson et al.2017). cAMP produced by Mtb in the presence of propionate or its metabolites may control the accumulation of propionyl-coA. While BCG grown on propionate does not produce higher levels of cAMP than BCG grown on glycerol at the population level (Nambi et al.2013; Johnson et al.2017), the possibility that cAMP levels in subcellular domains are being elevated by propionate cannot be ruled out. The expression of KATbcg is higher when BCG is grown on propionate than glucose (Nambi et al.2013), suggesting that BCG also regulates PAT activity at the transcriptional level. Better characterization of the molecular mechanisms that link cAMP to specific metabolic pathways, from ACs to effectors, is needed to fully determine the importance of cAMP signaling in mycobacteria.

Additional cAMP effector proteins in mycobacteria

A recent study showed that Rv1636 and its homolog in Msm, MSMEG_3811, lack canonical CNB domains but bind cAMP by a novel mechanism (Banerjee et al.2015). They also found that a majority of the cAMP in M. bovis BCG lysates is protein bound (Banerjee et al.2015). Rv1636 is an abundantly expressed universal stress protein (USP) and orthologs of Rv1636 are present in all mycobacterial genomes, including M. leprae where the sole USP ML1390 shares 89% identity with Rv1636 (O’Toole and Williams 2003).

Analysis of the crystal structure of MSMEG_3811 bound to cAMP identified several structural changes in an ATP-binding motif which may explain why it binds cAMP with higher affinity than ATP (Banerjee et al.2015). The biological function of Rv1636 is unknown, but Banarjee et al suggest that it regulates the release of ATP under stress. They propose that Rv1636 binds ATP when cAMP levels are low, but releases ATP into the cytoplasm when high levels of cAMP compete with ATP for binding (Banerjee et al.2015). This is an interesting hypothesis that merits further study.

Seven additional putative multifunctional cNT-binding proteins remain uncharacterized in Mtb, including the conserved hypothetical Rv0104 and proteins with CNB domains that are fused with transporter (Rv3728, Rv3239c, Rv2564, Rv0073), phospholipase (Rv3728, Rv2565) or mechanosensitive ion channel (Rv2434c) domains. CNBs fused with such functional domains are not found in other bacteria, suggesting that cAMP has multiple novel regulatory roles in mycobacteria that await discovery.

Mycobacterial cAMP modulates host response during infection

In addition to its roles in Mtb physiology, cAMP produced by Mtb affects interactions between the bacterium and host macrophages. Many bacterial pathogens secrete protein toxins that disrupt host cAMP signaling, but Mtb interferes with cAMP signaling by secreting bacterially derived cAMP directly into host cells (reviewed by McDonough and Rodriguez 2011; Dey and Bishai 2014).

The first indication that cAMP signaling is important to mycobacterial pathogenesis came in 1975 when Lowrie, Jackett and Ratcliffe (1975) showed that cAMP levels are elevated within macrophages infected by M. microti. The authors hypothesized that the bacteria were secreting cAMP into host phagosomes, and the degree of cAMP elevation within infected macrophages correlated with the ability of different bacterial species to prevent phagolysosome fusion (Lowrie, Jackett and Ratcliffe 1975; Lowrie, Aber and Jackett 1979). Thirty years would pass before cAMP levels within Mtb and M. bovis BCG were shown to also be elevated upon macrophage infection, and that the source of the elevated cAMP found in macrophage lysates is bacterially derived (Agarwal and Bishai 2009; Bai, Schaak and McDonough 2009).

Mtb with the AC Rv0386 ORF disrupted by a transposon is attenuated for survival in a murine infection model (Agarwal and Bishai 2009). Experiments using bacteria grown on 14C glycerol showed that the Rv0386-deficient strain secretes less bacterially derived cAMP into the host cytosol of macrophages. Additional studies showed that this mycobacterially derived cAMP increases levels of TNF-α in macrophages (Agarwal and Bishai 2009). In contrast, increasing the amount of Mtb's cAMP secretion by V-58-mediated induction of AC Rv1625 (Johnson et al.2017) suppresses TNF-α levels in Mtb-infected macrophages (Johnson et al.2017). This TNF-α suppression is consistent with other reports of cAMP driving an anti-inflammatory response in macrophages (Serezani et al.2008). The reasons underlying the different effects of Mtb-derived cAMP on host macrophages are not clear, but may depend on the amount, timing and/or source of cAMP production.

Mtb may also use cAMP to control the expression of small RNAs (sRNAs), such as Mcr11, which is located between the Rv1264 ORF that encodes a pH-sensitive AC and the conserved hypothetical protein Rv1265 that is regulated by Cmr (Gazdik and McDonough 2005). Mtb and BCG increase Mcr11 expression in macrophage-associated conditions (DiChiara et al.2010), and Mtb expresses Mcr11 during murine infection (Pelly, Bishai and Lamichhane 2012). Pelly, Bishai and Lamichhane (2012) also demonstrated that Mcr11 expression is elevated by the addition of dibutryl cAMP to Mtb cultures. Mcr11’s proximity to the Rv1264 ORF and regulation by cAMP suggest that this sRNA has important connections to cAMP metabolism in Mtb, which should be characterized further.

Much work remains to fully elucidate the role of cAMP in mycobacterial pathogenesis. For example, cAMP also contributes to Mtb growth on cholesterol, but the underlying mechanism is not clear (VanderVen et al.2015; Johnson et al.2017). V-58, the specific inducer of AC Rv1625c, inhibits Mtb growth on cholesterol as well as within macrophages (VanderVen et al.2015). Identification of the downstream effector(s) that respond to the excess cAMP and elucidating the connection between cAMP and cholesterol metabolism will provide important insights into the role of cAMP signaling as a regulator of cholesterol utilization in Mtb.

Understanding how Mtb uses its numerous ACs and cAMP-binding effectors to specifically regulate multiple processes with a single small molecule will require the generation of new tools to study individual ACs in live bacteria. The discovery of the Rv1625c-inducing compound V-58 marks the first such reagent, and allows for a single mycobacterial AC to be rapidly and specifically stimulated. Moving forward, more small molecule activators and inhibitors of ACs, the Rv0805 PDE and individual cAMP effector proteins are needed to tease apart the myriad of potential cAMP signaling pathways used by Mtb.

Beyond cAMP: cyclic di-nucleotides come in many forms

Bacteria also use cyclic-di-nucleotides (cdNs) as signaling molecules, with c-di-GMP identified in 1987, c-di-AMP in 2008 and most recently 2΄3 ΄-cGAMP in 2012 (Ross et al.1987; Witte et al.2008; Davies et al.2012). While less is known about cdNs than cAMP, characterizing the roles of cdNs is a very active area of investigation. Mammalian innate immune cells produce 2΄5 ΄-cGAMP in response to cytosolic microbial DNA and cdNs (Ablasser et al.2013) and 2΄5 ΄-cGAMP signaling is important for innate immune control of Mtb infection (Collins et al.2015). However, Mtb produces only c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP, so we will discuss recent findings regarding the role of these cdNs in mycobacteria.

c-di-AMP was first discovered in a crystal structure of the DNA integrity scanning protein (DisA) from Thermotoga maritima (Witte et al.2008). It is an essential signaling molecule for multiple species of Gram-positive bacteria, regulating processes such as cell wall homeostasis, potassium uptake and central metabolism (reviewed by Corrigan and Grundling 2013). The role of c-di-AMP in mycobacteria is less clear, although its presence impacts Mtb virulence.

c-di-AMP: di-adenylyl cyclases, PDEs and effector proteins

Di-adenylyl cyclases (DACs) convert two molecules of ATP or ADP into c-di-AMP, while PDEs with conserved DHH-DHHA1 or HD domains hydrolyze the cyclic bond of c-di-AMP to form either linear pApA or two molecules of AMP (Huynh and Woodward 2016). Mtb has one DAC, DisA (Rv3586), capable of synthesizing c-di-AMP from ATP or ADP (Bai et al.2012), and a single DHH-DHHA1 PDE (CnpB, Rv2837c) that cleaves c-di-AMP exclusively to AMP (Yang et al.2014). Purified DisA displays higher activity at pH 8 than at pH 6 using ATP as a substrate, but its c-di-AMP synthesis is pH independent when ADP is provided (Bai et al.2012).

Mtb DisA oligomerizes to form an enzymatically active homo-octomer in solution, and both N and C terminal portions of the protein are required for proper DisA oligomerization and activity (Bai et al.2012). The DisA ortholog from Bacillus subtilis forms a homo-octomer that senses DNA damage to delay sporulation (Bejerano-Sagie et al.2006; Campos et al.2014, reviewed by Corrigan and Grundling 2013). No similar role for DisA has been reported for mycobacteria, but c-di-AMP synthesis by the DisA homolog in M. smegmatis (DisA) is repressed by direct interaction with radiation-sensitive protein A (RadA), supporting a potential role for c-di-AMP as a regulator of DNA repair (Zhang and He 2013). The relationship between RadA and DACs may be conserved among bacteria, as the genes encoding them are adjacent to one another in many genomes, including those of M. smegmatis and Mtb (Zhang and He 2013).

CnpB (Rv2837c) is the primary PDE responsible for degrading c-di-AMP to AMP in a two-step reaction (Yang et al.2014). Purified Mtb CnpB readily hydrolyzes c-di-AMP as well as linear pApA or pGpG di-nucleotides (Manikandan et al.2014; Yang et al.2014; He et al.2016; Dey et al.2017). CnpB is less active against c-di-GMP than c-di-AMP in vitro, but CnpB may regulate c-di-GMP levels in intact bacteria. c-di-GMP levels are higher in a Mtb ΔcnpB strain than in wild-type Mtb (Dey et al.2017). Overexpression of CnpB in M. smegmatis decreases c-di-AMP levels 10-fold and reduces c-di-GMP levels 4-fold (He et al.2016). The crystal structure of CnpB bound to 5΄-pApA allows c-di-GMP to be modeled into the CnpB active site, suggesting that c-di-GMP may also be a substrate (He et al.2016). More work needs to be done to determine the role of CnpB as a modulator of both c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP in live Mtb cells.

The only mycobacterial c-di-AMP effector protein identified is DarR, a TF in M. smegmatis. c-di-AMP indirectly regulates fatty acid metabolism in non-pathogenic M. smegmatis by allosterically enhancing the DNA-binding ability of DarR to repress expression of three target genes, including one encoding a fatty-acyl-CoA ligase (Zhang, Li and He 2013). However, there is no DarR ortholog in virulent mycobacteria, no c-di-AMP effector proteins have been identified in Mtb and c-di-AMP was not shown to directly control regulation by DarR (Zhang, Li and He 2013).

c-di-AMP affects Mtb pathogenesis

Unlike cAMP, c-di-AMP is not produced by mammalian cells, but rather serves as an alarm signal eliciting a robust type I interferon response through the cytosolic surveillance pathway (CSP). C-di-AMP is the primary CSP-activating small molecule secreted by the intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes (Woodward, Iavarone and Portnoy 2010).

c-di-AMP is not essential to Mtb in vitro and deletion of disA in Mtb has only a mild effect on bacterial growth in broth culture (Yang et al.2014; Dey et al.2015). However, Mtb mutants lacking cnpB are severely attenuated in both macrophages and murine models of infection (Yang et al.2014; Dey et al.2015, 2017). Deletion of the c-di-AMP PDE cnpB (Rv2837c) in Mtb or BCG causes a large elevation in c-di-AMP levels within bacterial lysates and the extracellular medium. Increased secretion of c-di-AMP corresponds with induction of the type I IFN response, and macrophages infected with Mtb ΔcnpB mutants produce much higher levels of IFN-β than cells infected with wild-type Mtb or BCG (Yang et al.2014; Zhang, Yang and Bai 2018). DisA overexpression also attenuates Mtb virulence, suggesting that disregulated production of c-di-AMP is detrimental to Mtb pathogenesis (Dey et al.2015, 2017).

Retention of DisA by Mtb suggests that c-di-AMP benefits the bacteria, but little is known about specific molecular pathways that are regulated by c-di-AMP or its role within Mtb. While disregulated accumulation of c-di-AMP is deleterious to Mtb's survival during infection, Mtb may use appropriately regulated secretion of c-di-AMP to modulate host cell signaling to promote pathogenesis. Listeria monocytogenes secretes c-di-AMP via MDR efflux pumps including MdrM (Woodward, Iavarone and Portnoy 2010), and it is possible that Mtb also uses one of its many MDR efflux pumps to secrete c-di-AMP as well. Given the robust and productive immune response generated by Mtb mutants that secrete excess c-di-AMP, understanding of the bacterial factors involved could be leveraged for the development of novel anti-mycobacterial therapies and vaccine development.

C-di-GMP in mycobacteria

C-di-GMP is another bacteria-specific second messenger (Ross et al.1987). C-di-GMP is widespread among bacteria, and is involved in regulating diverse physiological processes including development, motility, biofilm formation and virulence (reviewed by Jenal, Reinders and Lori 2017). Like c-di-AMP, c-di-GMP is sensed as an alarmone by the mammalian immune system (Karaolis et al.2007).

C-di-GMP is synthesized from two GTP molecules by di-guanyl cyclases (DGCs), which contain conserved GGDEF domains, named for the key active site residues required for DGC activity. PDEs, with characteristic EAL or HD-GYP domains, are responsible for hydrolyzing c-di-GMP to form linear pGpG. In many bacteria, including Mtb, GGDEF and EAL domains are found in tandem within one polypeptide (GGDEF-EAL), allowing a single enzyme to control both the synthesis and degradation of c-di-GMP. Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae have 36 and 53 GGDEF-EALs, respectively. However Mtb, M. bovis and M. smegmatis each have only a single GGDEF-EAL DGC encoded by Rv1354c (MtbDGC) or its orthologs (Kumar and Chatterji 2008; Hengge 2009; Gupta, Kumar and Chatterji 2010). Mtb also has a second EAL PDE, Rv1357c, that is biochemically active in vitro (Gupta, Kumar and Chatterji 2010). As previously mentioned, the c-di-AMP PDE CnpB is able to hydrolyze c-di-GMP despite the absence of an EAL domain, suggesting that there is crosstalk between c-di-GMP and c-di-AMP in mycobacteria.

Most of what is known about mycobacterial c-di-GMP signaling has been characterized using the model organism M. smegmatis. Kumar and Chatterji (2008) were the first to show that mycobacteria produce c-di-GMP. They reported that MSMEG_2916 (DcpA) is a GGDEF-EAL enzyme with both DGC and PDE activities in vitro, and is responsible for producing c-di-GMP in M. smegmatis (Kumar and Chatterji 2008). Deletion of dcpA, and loss of c-di-GMP, does not affect biofilm formation in M. smegmatis, but the dcpA-KO strain is attenuated for survival under nutrient limitation (Kumar and Chatterji 2008). The Mtb DcpA homolog, MtbDGC, has also DGC and PDE activities in vitro, and can rescue the survival of dcpA-deficient M. smegmatis during starvation (Gupta, Kumar and Chatterji 2010).

Two c-di-GMP binding TFs have been identified as downstream effectors in mycobacteria, including LtmA from M. smegmatis and EthR (Rv3855) from Mtb. C-di-GMP enhances the binding of both TFs to DNA (Li and He 2012; Zhang et al.2017). LtmA binds and activates 37 target genes, including many involved in lipid transport or metabolism (Li and He 2012). Thirty potential Mtb c-di-GMP effector proteins from a protein microarray bound to biotinylated c-di-GMP in vitro, including Rv1525 (Wbbl2), Rv3420c (RimI), Rv3756c (ProZ) and Rv3855 (EthR) (Deng et al.2014). Follow-up work showed that expression of the Mtb ethR (Rv3855) gene, which encodes the TetR family TF EthR, protects M. smegmatis against the second-line drug ethionamide (ETH). ETH is a prodrug, which becomes activated by the mycobacterial monooxygenase EthA (Zhang et al.2017). C-di-GMP is protective, likely because enhanced EthR activity represses the expression of ethA, thereby reducing the concentration of active ETH in the bacterial cytoplasm (Zhang et al.2017). These findings need to be validated in Mtb to determine their significance to Mtb biology.

While cAMP and c-di-AMP produced by Mtb affect the course of infection at the macrophage level, the role of c-di-GMP in TB pathogenesis is less clear (Fig. 3). Future studies should address questions of cNT signal specificity, crosstalk and modulation. Another aspect of Mtb pathogenesis in which cNT signaling should be addressed is the bacterium's ability to enter a non-replicating persistent state (NRP), allowing the bacterium to survive for extended periods of time and resist treatment with antibiotics that target actively dividing bacilli. Little is known regarding the role of cNT signaling during persistence and latent infection in Mtb. However, given cAMP’s association with cholesterol, central carbon metabolism and the DosR regulon in Mtb, cAMP, and possibly other cNTs are also likely to play important roles during adaptation and survival of NRP. The major importance of cNTs to Mtb biology is only just beginning to be appreciated, and this area promises to be a fruitful area of future investigation.

Figure 3.

Model for cNT signaling in Mtb. Mtb produces the cNT second messengers cAMP, c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP to control key bacterial processes. Despite differences between the specific molecular players, all three signaling pathways involve nucleotide cyclases (pale blue), PDEs (red) and protein effectors (blue). Additionally, all three cNTs play important roles in interspecies signaling between Mtb and mammalian innate immune cells. More work is required to determine the specific signaling outcomes for each cNT pathway, and to identify the exact roles played by cNTs during different stages of Mtb infection.

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R01AI063499 and R21AI131679 to KAM. RMJ was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease training grant T32AI055429.

Conflict of Interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Abdel Motaal A, Tews I, Schultz JE et al. Fatty acid regulation of adenylyl cyclase Rv2212 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. FEBS J 2006;273:4219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ablasser A, Goldeck M, Cavlar T et al. cGAS produces a 2'-5'-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature 2013;498:380–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal N, Bishai WR. cAMP signaling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Indian J Exp Biol 2009;47:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal N, Lamichhane G, Gupta R et al. Cyclic AMP intoxication of macrophages by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis adenylate cyclase. Nature 2009;460:98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alasbahi RH, Melzig MF. Forskolin and derivatives as tools for studying the role of cAMP. Pharmazie 2012;67:5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Gazdik MA, Schaak DD et al. The Mycobacterium bovis BCG cyclic AMP receptor-like protein is a functional DNA binding protein in vitro and in vivo, but its activity differs from that of its M. tuberculosis ortholog, Rv3676. Infect Immun 2007;75:5509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Knapp GS, McDonough KA. Cyclic AMP signalling in mycobacteria: redirecting the conversation with a common currency. Cell Microbiol 2011;13:349–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, McCue LA, McDonough KA. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3676 (CRPMt), a cyclic AMP receptor protein-like DNA binding protein. J Bacteriol 2005;187:7795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Schaak DD, McDonough KA. cAMP levels within Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG increase upon infection of macrophages. FEMS Immunol Med Mic 2009;55:68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Schaak DD, Smith EA et al. Dysregulation of serine biosynthesis contributes to the growth defect of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis crp mutant. Mol Microbiol 2011;82:180–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Yang J, Zhou X et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3586 (DacA) is a diadenylate cyclase that converts ATP or ADP into c-di-AMP. PLoS One 2012;7:e35206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Adolph RS, Gopalakrishnapai J et al. A universal stress protein (USP) in mycobacteria binds cAMP. J Biol Chem 2015;290:12731–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barovsky K, Pedone C, Brooker G. Distinct mechanisms of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation and forskolin-potentiated hormone responses in C6-2B cells. Mol Pharmacol 1984;25:256–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Be NA, Lamichhane G, Grosset J et al. Murine model to study the invasion and survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the central nervous system. J Infect Dis 2008;198:1520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejerano-Sagie M, Oppenheimer-Shaanan Y, Berlatzky I et al. A checkpoint protein that scans the chromosome for damage at the start of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 2006;125:679–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Dods RF. Development of a Mn2+-sensitive, "soluble" adenylate cyclase in rat testis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1975;72:1097–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun T, Frank H, Dods R et al. Mn2+-sensitive, soluble adenylate cyclase in rat testis differentiation from other testicular nucleotide cyclases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1977;481:227–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier NA, Newton GL, Koledin T et al. Association of mycothiol with protection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from toxic oxidants and antibiotics. Mol Microbiol 2003;47:1723–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby S, Ebright RH. Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP). J Mol Biol 1999;293:199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos SS, Ibarra-Rodriguez JR, Barajas-Ornelas RC et al. Interaction of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases Nfo and ExoA with the DNA integrity scanning protein DisA in the processing of oxidative DNA damage during Bacillus subtilis spore outgrowth. J Bacteriol 2014;196:568–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann M. Bicarbonate stimulated adenylyl cyclases. IUBMB Life 2004;56:529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano-Cerezo S, Bernal V, Blanco-Catala J et al. cAMP-CRP co-ordinates the expression of the protein acetylation pathway with central metabolism in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 2011;82:1110–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JM, Boy-Rottger S, Dhar N et al. EspD is critical for the virulence-mediating ESX-1 secretion system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 2012;194:884–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Cann MJ, Litvin TN et al. Soluble adenylyl cyclase as an evolutionarily conserved bicarbonate sensor. Science 2000;289:625–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary E, Bishai W, Agarwal N. Expression of a subset of heat stress induced genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is regulated by 3',5'-cyclic AMP. PLoS One 2014;9:e89759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 1998;393:537–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AC, Cai H, Li T et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune DNA sensor for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Host Microbe 2015;17:820–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan RM, Grundling A. Cyclic di-AMP: another second messenger enters the fray. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013;11:513–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalebroux ZD, Svensson SL, Gaynor EC et al. ppGpp conjures bacterial virulence. Microbiol Mol Biol R 2010;74:171–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies BW, Bogard RW, Young TS et al. Coordinated regulation of accessory genetic elements produces cyclic di-nucleotides for V. cholerae virulence. Cell 2012;149:358–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J, Bi L, Zhou L et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteome microarray for global studies of protein function and immunogenicity. Cell Rep 2014;9:2317–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey B, Bishai WR. Crosstalk between Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the host cell. Semin Immunol 2014;26:486–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey B, Dey RJ, Cheung LS et al. A bacterial cyclic dinucleotide activates the cytosolic surveillance pathway and mediates innate resistance to tuberculosis. Nat Med 2015;21:401–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey RJ, Dey B, Zheng Y et al. Inhibition of innate immune cytosolic surveillance by an M. tuberculosis phosphodiesterase. Nat Chem Biol 2017;13:210–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiChiara JM, Contreras-Martinez LM, Livny J et al. Multiple small RNAs identified in Mycobacterium bovis BCG are also expressed in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:4067–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrt S, Schnappinger D. Mycobacterial survival strategies in the phagosome: defence against host stresses. Cell Microbiol 2009;11:1170–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann RD, Alland D, Eisen JA et al. Whole-genome comparison of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical and laboratory strains. J Bacteriol 2002;184:5479–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune SM, Jaeger A, Sarracino DA et al. Mutually dependent secretion of proteins required for mycobacterial virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:10676–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganaie AA, Trivedi G, Kaur A et al. Interaction of Erp protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with Rv2212 enhances intracellular survival of Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol 2016;198:2841–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdik MA, Bai G, Wu Y et al. Rv1675c (cmr) regulates intramacrophage and cyclic AMP-induced gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-complex mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol 2009;71:434–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdik MA, McDonough KA. Identification of cyclic AMP-regulated genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria under low-oxygen conditions. J Bacteriol 2005;187:2681–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomelsky M. cAMP, c-di-GMP, c-di-AMP and now cGMP: bacteria use them all! Mol Microbiol 2011;79:562–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger DC, Hurd D, Harrison M et al. Studies of the distribution of Escherichia coli cAMP-receptor protein and RNA polymerase along the E. coli chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:17693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Stapleton MR, Smith LJ et al. Cyclic-AMP and bacterial cyclic-AMP receptor proteins revisited: adaptation for different ecological niches. Curr Opin Microbiol 2014;18:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JE, Gawronski JD, Dejesus MA et al. High-resolution phenotypic profiling defines genes essential for mycobacterial growth and cholesterol catabolism. PLoS Pathog 2011;7:e1002251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo YL, Seebacher T, Kurz U et al. Adenylyl cyclase Rv1625c of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a progenitor of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. EMBO J 2001;20:3667–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K, Kumar P, Chatterji D. Identification, activity and disulfide connectivity of C-di-GMP regulating proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 2010;5:e15072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman T, Weinrick B, Vilcheze C et al. Succinate dehydrogenase is the regulator of respiration in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog 2014;10:e1004510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden JD, Brown LR, Gunawardena HP et al. Reversible acetylation regulates acetate and propionate metabolism in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 2013;159:1986–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Wang F, Liu S et al. Structural and biochemical insight into the mechanism of Rv2837c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a c-di-NMP phosphodiesterase. J Biol Chem 2016;291:14386–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009;7:263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh TN, Woodward JJ. Too much of a good thing: regulated depletion of c-di-AMP in the bacterial cytoplasm. Curr Opin Microbiol 2016;30:22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson EK. The 2',3'-cAMP-adenosine pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2011;301:F1160–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenal U, Reinders A, Lori C. Cyclic di-GMP: second messenger extraordinaire. Nat Rev Microbiol 2017;15:271–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RM, Bai G, DeMott CM et al. Chemical activation of adenylyl cyclase Rv1625c inhibits growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis on cholesterol and modulates intramacrophage signaling. Mol Microbiol 2017;105:294–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetsky M, Middelhaufe S, Bank EM et al. Molecular details of cAMP generation in mammalian cells: a tale of two systems. J Mol Biol 2006;362:623–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaolis DK, Means TK, Yang D et al. Bacterial c-di-GMP is an immunostimulatory molecule. J Immunol 2007;178:2171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppetipola N, Shuman S. A phosphate-binding histidine of binuclear metallophosphodiesterase enzymes is a determinant of 2΄,3΄-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity. J Biol Chem 2008;283:30942–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp GS, Lyubetskaya A, Peterson MW et al. Role of intragenic binding of cAMP responsive protein (CRP) in regulation of the succinate dehydrogenase genes Rv0249c-Rv0247c in TB complex mycobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:5377–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp GS, McDonough KA. Cyclic AMP signaling in mycobacteria. Microbiol Spectr 2014;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Chatterji D. Cyclic di-GMP: a second messenger required for long-term survival, but not for biofilm formation, in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 2008;154:2942–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Lang PT, Fortune SM et al. Cyclic AMP regulation of protein lysine acetylation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2012;19:811–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, VanderVen BC, Fahey RJ et al. Intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis exploits host-derived fatty acids to limit metabolic stress. J Biol Chem 2013;288:6788–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KN, Liao R, Guinn KM et al. Deletion of RD1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis mimics bacille Calmette-Guerin attenuation. J Infect Dis 2003;187:117–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Gu J, Chen P et al. Purification and characterization of the acetyl-CoA synthetase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2011;43:891–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, He ZG. LtmA, a novel cyclic di-GMP-responsive activator, broadly regulates the expression of lipid transport and metabolism genes in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40:11292–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder JU, Schultz A, Schultz JE. Adenylyl cyclase Rv1264 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis has an autoinhibitory N-terminal domain. J Biol Chem 2002;277:15271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrie DB, Aber VR, Jackett PS. Phagosome-lysosome fusion and cyclic adenosine 3':5'-monophosphate in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium microti, Mycobacterium bovis BCG or Mycobacterium lepraemurium. J Gen Microbiol 1979;110:431–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrie DB, Jackett PS, Ratcliffe NA. Mycobacterium microti may protect itself from intracellular destruction by releasing cyclic AMP into phagosomes. Nature 1975;254:600–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue LA, McDonough KA, Lawrence CE. Functional classification of cNMP-binding proteins and nucleotide cyclases with implications for novel regulatory pathways in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res 2000;10:204–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough KA, Rodriguez A. The myriad roles of cyclic AMP in microbial pathogens: from signal to sword. Nat Rev Micro 2012;10:27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGurn JA, Raghavan S, Stanley SA et al. A non-RD1 gene cluster is required for Snm secretion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 2005;57:1653–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan K, Sabareesh V, Singh N et al. Two-step synthesis and hydrolysis of cyclic di-AMP in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 2014;9:e86096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matange N, Hunt DM, Buxton RS et al. Overexpression of the Rv0805 phosphodiesterase elicits a cAMP-independent transcriptional response. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2013;93:492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matange N, Podobnik M, Visweswariah SS. The non-catalytic “cap domain” of a mycobacterial metallophosphoesterase regulates its expression and localization in the cell. J Biol Chem 2014;289:22470–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamolova GV, Turapov OA, Young DI et al. A family of autocrine growth factors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 2002;46:623–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Elias EJ, Upton AM, Cherian J et al. Role of the methylcitrate cycle in Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism, intracellular growth, and virulence. Mol Microbiol 2006;60:1109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambi S, Basu N, Visweswariah SS. cAMP-regulated protein lysine acetylases in mycobacteria. J Biol Chem 2010;285:24313–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambi S, Gupta K, Bhattacharyya M et al. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein lysine acylation in mycobacteria regulates fatty acid and propionate metabolism. J Biol Chem 2013;288:14114–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noy T, Xu H, Blanchard JS. Acetylation of acetyl-CoA synthetase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis leads to specific inactivation of the adenylation reaction. Arch Biochem Biophys 2014;550-551:42–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole R, Williams HD. Universal stress proteins and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Res Microbiol 2003;154:387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelly S, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G. A screen for non-coding RNA in Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals a cAMP-responsive RNA that is expressed during infection. Gene 2012;500:85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picossi S, Flores E, Herrero A. ChIP analysis unravels an exceptionally wide distribution of DNA binding sites for the NtcA transcription factor in a heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium. BMC Genomics 2014;15:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters J, Gatfield J. Hijacking the host: survival of pathogenic mycobacteria inside macrophages. Trends Microbiol 2002;10:142–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podobnik M, Tyagi R, Matange N et al. A mycobacterial cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase that moonlights as a modifier of cell wall permeability. J Biol Chem 2009;284:32846–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pym AS, Brodin P, Brosch R et al. Loss of RD1 contributed to the attenuation of the live tuberculosis vaccines Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium microti. Mol Microbiol 2002;46:709–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall TW, Sutherland EW. Formation of a cyclic adenine ribonucleotide by tissue particles. J Biol Chem 1958;232:1065–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan S, Bai G, Lyubetskaya A et al. Characterization of a cAMP responsive transcription factor, Cmr (Rv1675c), in TB complex mycobacteria reveals overlap with the DosR (DevR) dormancy regulon. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:134–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan S, Cheung J, Cassidy M et al. Novel structural features drive DNA binding properties of Cmr, a CRP family protein in TB complex mycobacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, DOI 10.1093/nar/gkx1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MC, Palaninathan SK, Bruning JB et al. Structural insights into the mechanism of the allosteric transitions of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cAMP receptor protein. J Biol Chem 2009;284:36581–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SK, Kamireddi M, Dhanireddy K et al. Eukaryotic-like adenylyl cyclases in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: cloning and characterization. J Biol Chem 2001;276:35141–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickman L, Scott C, Hunt DM et al. A member of the cAMP receptor protein family of transcription regulators in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for virulence in mice and controls transcription of the rpfA gene coding for a resuscitation promoting factor. Mol Microbiol 2005;56:1274–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romling U. Great times for small molecules: c-di-AMP, a second messenger candidate in Bacteria and Archaea. Sci Signal 2008;1:pe39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross P, Weinhouse H, Aloni Y et al. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 1987;325:279–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:12989–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savvi S, Warner DF, Kana BD et al. Functional characterization of a vitamin B12-dependent methylmalonyl pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for propionate metabolism during growth on fatty acids. J Bacteriol 2008;190:3886–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serezani CH, Ballinger MN, Aronoff DM et al. Cyclic AMP: master regulator of innate immune cell function. Am J Resp Cell Mol 2008;39:127–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Capuder M, Draskovic P et al. Structural and biochemical analysis of the Rv0805 cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Biol 2007;365:211–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Sivakumar K, Krupa A et al. A survey of nucleotide cyclases in actinobacteria: unique domain organization and expansion of the class III cyclase family in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Comp Funct Genomics 2004;5:17–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Sreenath N, Podobnik M et al. The Rv0805 gene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes a 3',5'-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase: biochemical and mutational analysis. Biochemistry 2005;44:15695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Visweswariah SS. New messages from old messengers: cAMP and mycobacteria. Trends Microbiol 2006;14:543–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LJ, Bochkareva A, Rolfe MD et al. Cmr is a redox-responsive regulator of DosR that contributes to M. tuberculosis virulence. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:6600–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springett GM, Kawasaki H, Spriggs DR. Non-kinase second-messenger signaling: new pathways with new promise. Bioessays 2004;26:730–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton M, Haq I, Hunt DM et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis cAMP receptor protein (Rv3676) differs from the Escherichia coli paradigm in its cAMP binding and DNA binding properties and transcription activation properties. J Biol Chem 2010;285:7016–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland EW, Rall TW. Fractionation and characterization of a cyclic adenine ribonucleotide formed by tissue particles. J Biol Chem 1958;232:1077–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tews I, Findeisen F, Sinning I et al. The structure of a pH-sensing mycobacterial adenylyl cyclase holoenzyme. Science 2005;308:1020–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresguerres M, Levin LR, Buck J. Intracellular cAMP signaling by soluble adenylyl cyclase. Kidney Int 2011;79:1277–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi R, Shenoy AR, Visweswariah SS. Characterization of an evolutionarily conserved metallophosphoesterase that is expressed in the fetal brain and associated with the WAGR syndrome. J Biol Chem 2009;284:5217–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton AM, McKinney JD. Role of the methylcitrate cycle in propionate metabolism and detoxification in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 2007;153:3973–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderVen BC, Fahey RJ, Lee W et al. Novel inhibitors of cholesterol degradation in mycobacterium tuberculosis reveal how the bacterium's metabolism is constrained by the intracellular environment. PLoS Pathog 2015;11:e1004679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte G, Hartung S, Buttner K et al. Structural biochemistry of a bacterial checkpoint protein reveals diadenylate cyclase activity regulated by DNA recombination intermediates. Mol Cell 2008;30:167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA. c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science 2010;328:1703–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Hegde SS, Blanchard JS. Reversible acetylation and inactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis acetyl-CoA synthetase is dependent on cAMP. Biochemistry 2011;50:5883–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Bai Y, Zhang Y et al. Deletion of the cyclic di-AMP phosphodiesterase gene (cnpB) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis leads to reduced virulence in a mouse model of infection. Mol Microbiol 2014;93:65–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HN, Xu ZW, Jiang HW et al. Cyclic di-GMP regulates Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance to ethionamide. Sci Rep 2017;7:5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, He ZG. Radiation-sensitive gene A (RadA) targets DisA, DNA integrity scanning protein A, to negatively affect cyclic Di-AMP synthesis activity in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Biol Chem 2013;288:22426–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Li W, He ZG. DarR, a TetR-like transcriptional factor, is a cyclic di-AMP-responsive repressor in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Biol Chem 2013;288:3085–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yang J, Bai G. Cyclic di-AMP-mediated interaction between Mycobacterium tuberculosis ΔcnpB and macrophages implicates a novel strategy for improving BCG vaccination. Pathog Dis 2018; 76, DOI 10.1093/femspd/fty008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]