Abstract

We have conducted an analysis of azaspiro[3.3]heptanes used as replacements for morpholines, piperidines, and piperazines in a medicinal chemistry context. In most cases, introducing a spirocyclic center lowered the measured logD7.4 of the corresponding molecules by as much as −1.0 relative to the more usual heterocycle. This may seem counterintuitive, as the net change in the molecule is the addition of a single carbon atom, but it may be rationalized in terms of increased basicity. An exception to this was found with N-linked 2-azaspiro[3.3]heptane, where logD7.4 increased by as much as +0.5, consistent with the addition of carbon. During our investigation, we also concluded that azaspiro[3.3]heptanes are most likely not suitable bioisosteres for morpholines, piperidines, and piperazines, when not used as terminal groups, due to significant changes in their geometry.

Keywords: Lipophilicity, morpholine, piperazine, bioisostere

We recently reported our analysis of the counterintuitive phenomenon of one carbon bridged morpholines, piperazines, and piperidines, which displayed lower lipophilicity, despite the net addition of a single carbon atom.1 Another single carbon atom modification of these heterocycles, which also reduces lipophilicity, can be found in azaspiroheptanes, such as described in Figure 1. Conceptually, these spiro-analogues can be thought of as a progression from the bridged analogues, whereby the additional bridging atom is made quaternary and the C2–C3 and C5–C6 bonds of the parent are broken.

Figure 1.

Azaspiroheptane analogues of piperidine, morpholine, and piperazine.

The overall result is a different molecular topology in which the distance between the two terminal atoms increases and the orientation of the termini is given a 90° twist. In cases where X = N or O, the heteroatom is now γ rather than β to the nitrogen, reducing the amount of inductive electron withdrawal and resulting in an increased pKa. As shown in Figure 2, the quantum mechanics (QM) conformations of 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes and their piperazine variants vary significantly. In 1–4, the molecular volumes of the spiro-analogues are ∼9 to 13 Å3 larger than for the piperazines, consistent with the constrained geometry. The comparison between 2a and 2b shows that the azaspiroheptane base is positioned ∼1.3 Å further away than the piperazine. Such an effect alters the pKa of 2b, which is predicted to be significantly more basic than 2a (ΔpKa[ACD] = +1.9).

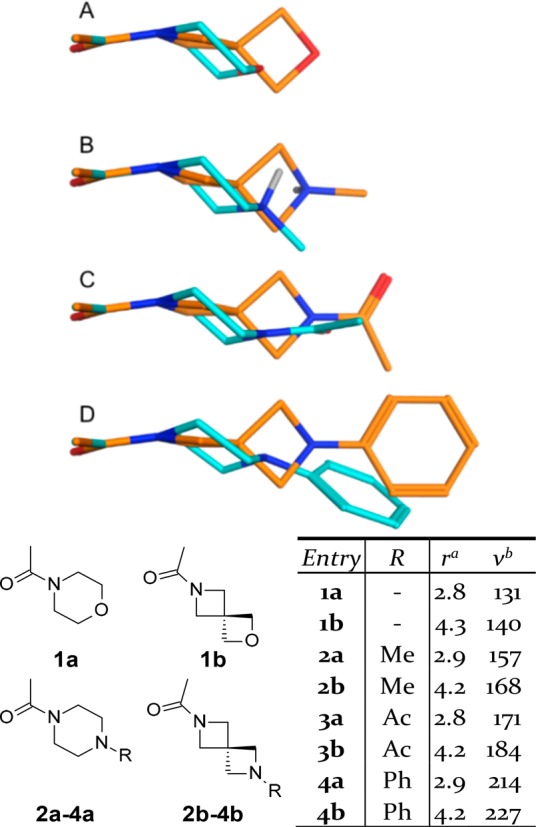

Figure 2.

Comparison of QM-minimized conformations for spiro-variants (orange) of morpholines and piperazines (cyan). aDistance (Å) between the two heteroatoms in the ring. bVolume (Å3).

Striking differences are seen when the base is capped with an acetyl (3a/3b) or a phenyl group (4a/4b). In 3b, the azaspiroheptane terminal acetyl O is both 2.2 Å further out and perpendicular compared to 3a, while in 4b the 4-position of the terminal phenyl is both 2.5 Å further out as well as being perpendicular. These QM-minimized conformations are in good agreement with those previously disclosed (e.g., CCDC code AKUQUT). These geometries indicate that although azaspiroheptanes may appear to be two-dimensional bioisosteric replacements for morpholines, piperazines, or piperidines, in three dimensions they are very different.

The synthesis of these azaspiroheptane analogues has been previously reported by Carreira and Wuitschik in pioneering publications from 2008 to 2010,2,3 with the logD7.4 lowering effect noted. Since then, the number of reported azaspiroheptanes has increased significantly, particularly in the patent literature. The purpose of this Letter is to share our experiences of working with these groups and review the recent literature, highlighting examples of these motifs being used by medicinal chemists. In addition, we have analyzed the AstraZeneca compound collection using molecular matched pair analysis (MMPA) for further understanding.

While looking to discover inhibitors of IRAK4, we made 5b as a spiro-analogue of morpholine 5a (Table 1).5 Expectantly, 5b exhibited higher basicity and lower lipophilicity (ΔpKa = +0.6, ΔlogD7.4 = −0.7), in agreement with similar reported examples (7a–b, Figure 3),2 with some marginal benefits in lipophilicity related properties. Although a small loss in cell potency (ΔpIC50 = −0.4) was observed, the lower lipophilicity made the change beneficial in terms of cell LLE (ΔLLE = +0.3). Analogue 5b displayed a small decrease in permeability (∼3-fold), which we attributed to the combination of lower lipophilicity and higher basicity. This 2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3.3]heptane group formed part of the structure of AZD1979 (6b),6 which also had a significantly higher basicity and lower lipophilicity relative to morpholine 6a (ΔpKa = +1.5, ΔlogD7.4 = −1.2). Despite this, 6b suffered no detrimental effect in permeability or hERG inhibition. Importantly, the turnover in human liver microsomes (HLM) and human/rat hepatocytes (HH/RH) was greatly reduced for 6b, representing a noteworthy consideration when working with these strained ring systems. A small molecule crystal structure of 6b showed the conformation of the spirobicycle (CCDC code IKEGAI) to be consistent with the modeling of 1b.

Table 1. Examples of Spiro-morpholines and Selected Lipophilicity-Related Properties.

| entry | R | logD7.4a | pKab | hERG IC50c | Caco2 Pappd | HLM CLinte | HH/RH CLintf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5a | A | 1.5 | 7.6 | >100 | 14 | <3 | <1/14 |

| 5b | B | 0.8 | 8.2 | >40 | 4.1 | <3 | <1/8 |

| 6a | A | 2.8 | 6.7 | 16 | 48 | 72 | 61/190 |

| 6b | B | 1.6 | 8.2 | 22 | 43 | 13 | 11/5.1 |

Shake-flask distribution coefficient.4

Measured pKa.

hERG inhibition.

Intrinsic permeability (10–6 cm/s).

Intrinsic clearance (μL/min/mg).

Intrinsic clearance (μL/min/106 cells).

Figure 3.

Selected examples of azaspiro[3.3]heptanes used as morpholine/piperazine replacements.

Other examples of 2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3.3]heptanes used as morpholine replacements are depicted in Figure 3. To tackle nonoxidative metabolism of linezolid 8a (Figure 3), spiro-morpholine 8b was proposed as a more stable bioisostere.7 It retained its antibacterial activity against multiple strains, but not against E. coli. Spiro-analogue 9b of artefenomel (9a) was also described with a similar lipophilicity effect (ΔpKa = +0.8, ΔlogD7.4 = −0.6), while maintaining potency.8 Other examples showed decreased potencies compared to their alkyl morpholine parent, including an 2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3.3]heptane analogue 10b of gefitinib (10a).9 Likewise, aryl 2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3.3]heptane 11b (analogue of LRRK2 inhibitor PF-06447475, 11a),10 Kv7 channel opener 12b,11 and cathepsin S inhibitor 13b(12) all displayed significant loss of potency. Unfortunately, no physicochemical data was reported for 10–13, but one could speculate that similar reductions in lipophilicity would have been observed.

Spiro-piperazines have also been used, whether as terminal groups (defined herein as attached to a group bearing no more than six heavy atoms, e.g., smaller than phenyl) or as replacement of a central scaffold (Figure 3). Early examples of both NMe (14b) and NAc (15b) 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes showed remarkably similar trends to 5b–7b (14b, ΔpKa = +1.4, ΔlogD7.4 = −1.0; 15b, ΔpKa = +1.3, ΔlogD7.4 = −0.9), and this was associated with lowered HLM metabolism.3 Recent SOS1 agonists showed a 3-fold improvement in binding for spiro-analogue 16b compared to 16a.13 This was consistent across three other matched pairs in this series. The authors postulated that this may be driven by increased rigidity of the 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptane relative to the piperazine, leading to a lower entropic binding penalty together with the increased basicity leading to a stronger ionic interaction with the protein. X-ray crystal structures of closely related analogues 17a and 17b (PDB codes 6D59 and 6D56, Figure 4A) demonstrated that the key interaction to Asp887 is conserved, despite the azaspiroheptane NH being located ∼1.2 Å farther from the piperazine NH. The pair of KHK inhibitors 18a–b showed similar potency in cells,14 and a similar distance between the two basic NHs was observed (∼1.3 Å, PDB codes 3Q92 and 3QAI, Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

X-ray structures of 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes used as piperazine replacements: (A) 17a (cyan) and 17b (orange); (B) 18a (cyan), 18b (orange). The azaspiroheptane base is shifted by ∼1.2–1.5 Å relative to the piperazine, consistent with Figure 2.

Other reported examples were not as successful: spirocyclic 19b, analogue of the noncovalent BTK clinical candidate GDC-0853 (19a) lost potency, in line with the lipophilicity drop, but showed no improvement in HLM.15 Similarly, the spirocyclic version 20b of olaparib (20a) was recently reported to lose a little potency, but interestingly gained selectivity within the PARP family.16

2,6-Diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes have also been investigated as piperazine replacements in a more central context (substitution of both termini with >6 heavy atoms). An example taken from our own experience involved a series of GPR119 agonists (Figure 5),17 where 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptane 21b resulted in a reduction in lipophilicity (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.3), despite both nitrogen atoms being nonbasic.

Figure 5.

QM-minimized geometries of a 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptane 21b (orange) used as a replacement of piperazine 21a (cyan). aGPR119 potency (μM). bIncubation at 10 μM (10–6 cm/s).

This was accompanied by improvements in hERG and HLM/RH stability, without significant detriment to MDCK permeability. However, there was a dramatic loss in potency (>800-fold) compared to the parent piperazine, indicating that the azaspiro[3.3]heptane is not a good bioisostere in this case. This was rationalized based on wider SAR, which had shown that the position and orientation of the carbamate acceptor group was crucial to activity. Here, the geometry of the carbonyl is significantly altered as illustrated in the proposed overlay of both minimum energy conformations.

This dramatic loss of primary potency appears to be mirrored in other reported nonterminal 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes (Figure 6). Approximately 100-fold loss of potency and no gain in selectivity was observed in the dopamine D3 receptor antagonist 22b,18 while GLUT-1 inhibitor 23b showed a smaller loss of potency against GLUT-3 than its intended target.19 The SCD inhibitor 24b was more successful in maintaining potency.20 Among examples where the 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptane is attached to two large substituents, 25b(21) (analogue of FAAH inhibitor JNJ-40355003 25a)22 and BCL-2/BCL-XL inhibitor 26b(23) both lost significant potency compared to the parent piperazine. In 26b, the decrease in logD7.4 was considerable and might have explained some of the potency drop. For examples 22–26, it can be argued that small conformational changes can result in dramatic consequences in overall shape, unless counterbalanced by other co-occurring structural changes.

Figure 6.

Selected examples of 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes used as replacements for nonterminal piperazines.

As seen in Figures 2, 4, and 5, the switch from piperazine to azaspiroheptane increases the distance between the two N atoms by ∼1.3 Å and induces a ∼90° twist in the molecule. In some specific cases these replacements may be beneficial, but where a piperazine spacer has been found to be optimal it would seem unlikely that a 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptane would provide an effective bioisostere.

2-Azaspiro[3.3]heptanes used as piperidine isosteres are less common, and only limited examples have been reported. Of note, we observed the C-linked CXCR2 antagonist 27b (Figure 7), reported to be about 2-fold more potent than 27a, but crucially for the project had 25-fold less brain penetration.24 While the authors invoked potential transporter effects, we would also hypothesize that the increased basicity of the spiro-analogue might have played an important role. The topical TACE inhibitor 28b also provides an interesting example where the motif occupies a slightly different place in the molecule.25 Among published N-linked 2-azaspiro[3.3]heptanes, we noted the early example 29b,26 which showed ∼10-fold improvement in antiproliferation of MCF-7 cells. In contrast, the negative allosteric modulators of mGlu2 30b proved to be inferior to the corresponding piperidine by about 10-fold.27 No relevant example was found where the 2-azaspiro[3.3]heptane motif was used as a central scaffold.

Figure 7.

Selected examples of 2-azaspiro[3.3]heptanes used as piperidine replacements.

In order to investigate these observations more broadly, we conducted a set of MMPA of the AstraZeneca compound collection, using a previously described methodology.1 Results for terminal groups are summarized in Figure 8 (data available in the SI), expressed as ΔlogD7.4 between azaspiroheptanes and the parent heterocycles.

Figure 8.

ΔlogD7.4 relative to parent: (A) 2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3.3]heptanes and 2-azaspiro[3.3]heptanes; (B) 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes. Error bars are shown for ±SD.

For 2,6-diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes, we looked at standard end groups such as NH, NMe, or NAc. We further subdivided the identified matched pairs according to the type of attachment: amides, arylamines, or more basic alkylamines. The lower lipophilicity of 2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3.3]heptanes (Figure 8A, red line) was observed across all three subcategories and was less pronounced in the neutral amides (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.17 ± 0.36, N = 9) than in the basic alkyl amines (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.75 ± 0.26, N = 10), while arylamines were somewhere in the middle (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.44 ± 0.28, N = 16). The difference in the magnitude of the effect between neutral and basic examples can be interpreted as the contribution of this phenomenon that is independent of basicity, i.e., a conformational effect. In contrast, all 2-azaspiro[3.3]heptanes (black line) tended to be more lipophilic than the parent piperidines, perhaps reflecting the increase in nonpolar volume brought about by the addition of carbon and lack of compensatory polarity increasing effect.

2,6-Diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes (Figure 8B) also demonstrated lower lipophilicity, in magnitudes very similar to the above examples. Only NAc matched pairs were found for all three subcategories, which were similar to spiro-morpholine examples. The effect was less pronounced in neutral amides (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.15 ± 0.33, N = 4) than in basic alkyl/aryl amines, although for these single pairs were identified (for both, ΔlogD7.4 = −0.80, N = 1) and thus the effect is not statistically significant. Fewer matched pairs were found for NH examples, where only amides and aryl amines were available, but all had lower logD than their piperazine counterparts. Amides appeared to show a larger lipophilicity decrease, although this was based on a couple of examples only (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.61 ± 0.58, N = 2). A small number of NH aryl amines were identified, which exhibited a smaller and tighter effect (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.58 ± 0.38, N = 4). In comparison, a greater number of NMe aryl amines were identified and showed approximately twice as large a decrease (ΔlogD7.4 = −1.12 ± 0.22, N = 9), presumably enhanced by a stronger pKa. It is also worth noting that an even larger number of C-linked NMe aryl piperidines/2-azaspiro[3.3]heptanes were found in our collection (data not shown), which also showed a large reduction (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.93 ± 0.12, N = 21), again a likely consequence of the increased basicity of NMe spiro-analogues.

Our interpretation of this effect on terminal azaspiro[3.3]heptanes is therefore that the change will result in lower lipophilicity for morpholine, piperazine, and C-linked 4-piperidine replacements, ranging from ΔlogD7.4 ≈ −0.2 for neutrals to −1.1 for the more basic analogues. For N-linked spiropiperidines, this will result in increased lipophilicity (ΔlogD7.4 ≈ +0.2 to +0.5).

As described earlier, the structural and data analyses suggest that azaspiro[3.3]heptanes may not always be effective bioisosteres of the corresponding six-membered heterocycles. We wanted to investigate if the lipophilicity-lowering effect was still a relevant medicinal chemistry strategy for examples where the spiroheterocycles occupy a central place in the molecule. Table 2 contains ΔlogD7.4 for molecules where both ends of the heterocycle bear groups with more than six heavy atoms (i.e., larger than phenyl).

Table 2. 2,6-Diazaspiro[3.3]heptanes Used as Nonterminal Groups.

ΔlogD7.4 relative to the parent piperazine.

N, number of observations.

The small set of matched pairs was divided in the same subcategories as above, on both ends. Unfortunately, only limited examples were available, and not all subcategories were represented. Despite lacking robust statistical significance, we believe that these are insightful, and we propose below an interpretation that is consistent with earlier observations. For example, the single amide matched pair of type A was consistent with observations made for NAc capped amides (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.20 and −0.15, respectively) and so were amides of type C compared to NAc-capped alkylamine (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.80 for both). Surprisingly, type B showed no difference, in contrast to NAc-capped arylamines (Figure 8B), but this was only measured on a single pair. The diazaspiroheptane/piperazine pair of type D (directly connected to two aryl groups) surprisingly showed a lower logD despite being fully neutral. The more basic aryl–alkyl type E showed a statistically significant impact, which is also consistent with NMe-capped aryl amines (ΔlogD7.4 = −0.81 ± 0.29, N = 14 and −1.12 ± 0.22, N = 9, respectively), while the couple of examples of type F (alkyl–alkyl) showed the strongest effect presumably due to a larger pKa difference. In summary, when the spiro-replacement occurs in the middle of molecules, similar trends are observed as when they appear in terminal positions, which is a lower logD7.4 by −0.2 to −1.0.

In conclusion, we have conducted an analysis of the literature and our compound collection to investigate the lipophilicity-lowering effect of azaspiro[3.3]heptanes relative to the corresponding six-membered heterocycles. In agreement with early literature findings, we observed a decrease in logD7.4 ranging from −0.2 to −1.0 for the most basic examples, which was found to be mostly due to increased basicity. Benefits for this change were often found to have increased metabolic stability and lower hERG activity, but we also noted potential detrimental effects linked to increased basicity, such as compromised permeability and, in one case, unfavorable CNS penetration. N-Linked 2-azaspiro[3.3]heptanes were found to be the exception and increased logD7.4 by +0.2 to +0.5, which is consistent with the addition of carbon to the molecule. Furthermore, during our investigation we concluded that, when not used as a terminal group, azaspiro[3.3]heptanes do not constitute suitable bioisosteres for morpholines, piperidines, and piperazines due to significant geometry changes for the spiro-analogues. We would therefore recommend the use of azaspiro[3.3]heptanes in cases where lower lipophilicity is needed and where the group is either in a terminal position or the geometry of the six-membered parent ring is suboptimal.

Acknowledgments

Paul Davey and Eva Lenz are thanked for the characterization of 5b and 21b, and William McCoull for his help with this manuscript.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- BCL-XL

B-Cell Lymphoma-eXtra Large

- BTK

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase

- CatS

cathepsin-S

- CXCR2

C–X–C motif chemokine receptor-2

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- GLUT-1

glucose transporter-1

- GPR119

G protein-coupled receptor-119

- IRAK4

interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-4

- KHK

KetoHexoKinase

- LRRK2

leucine-rich repeat kinase-2

- PARP1

poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase-1

- SCD

stearoyl-CoA desaturase

- SOS1

Son Of Sevenless homologue-1

- TACE

tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-α

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00248.

Syntheses of 5b and 21b and details about the pairwise analysis (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Degorce S. L.; Bodnarchuk M. S.; Cumming I. A.; Scott J. S. Lowering lipophilicity by adding carbon: one-carbon bridges of morpholines and piperazines. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 8934–8943. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuitschik G.; Rogers-Evans M.; Buckl A.; Bernasconi M.; Marki M.; Godel T.; Fischer H.; Wagner B.; Parrilla I.; Schuler F.; Schneider J.; Alker A.; Schweizer W. B.; Muller K.; Carreira E. M. Spirocyclic oxetanes: synthesis and properties. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4512–4515. 10.1002/anie.200800450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard J. A.; Wagner B.; Fischer H.; Schuler F.; Muller K.; Carreira E. M. Synthesis of azaspirocycles and their evaluation in drug discovery. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 3524–3527. 10.1002/anie.200907108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alelyunas Y. W.; Pelosi-Kilby L.; Turcotte P.; Kary M. B.; Spreen R. C. A high throughput dried DMSO LogD lipophilicity measurement based on 96-well shake-flask and atmospheric pressure photoionization mass spectrometry detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1217, 1950–1955. 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. S.; Degorce S. L.; Anjum R.; Culshaw J.; Davies R. M. D.; Davies N. L.; Dillman K. S.; Dowling J. E.; Drew L.; Ferguson A. D.; Groombridge S. D.; Halsall C. T.; Hudson J. A.; Lamont S.; Lindsay N. A.; Marden S. K.; Mayo M. F.; Pease J. E.; Perkins D. R.; Pink J. H.; Robb G. R.; Rosen A.; Shen M.; McWhirter C.; Wu D. Discovery and optimization of pyrrolopyrimidine inhibitors of Interleukin-1 Receptor Associated Kinase 4 (IRAK4) for the treatment of mutant MYD88L265P diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 10071–10091. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson A.; Lofberg C.; Antonsson M.; von Unge S.; Hayes M. A.; Judkins R.; Ploj K.; Benthem L.; Linden D.; Brodin P.; Wennerberg M.; Fredenwall M.; Li L.; Persson J.; Bergman R.; Pettersen A.; Gennemark P.; Hogner A. Discovery of (3-(4-(2-oxa-6-azaspiro[3.3]heptan-6-ylmethyl)phenoxy)azetidin-1-yl)(5-(4-methoxy phenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)methanone (AZD1979), a Melanin Concentrating Hormone Receptor 1 (MCHr1) antagonist with favorable physicochemical properties. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 2497–2511. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadekar P. K.; Roychowdhury A.; Kharkar P. S.; Khedkar V. M.; Arkile M.; Manek H.; Sarkar D.; Sharma R.; Vijayakumar V.; Sarveswari S. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel azaspiro analogs of linezolid as antibacterial and antitubercular agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 122, 475–487. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y.; Wang X.; Kamaraj S.; Bulbule V. J.; Chiu F. C.; Chollet J.; Dhanasekaran M.; Hein C. D.; Papastogiannidis P.; Morizzi J.; Shackleford D. M.; Barker H.; Ryan E.; Scheurer C.; Tang Y.; Zhao Q.; Zhou L.; White K. L.; Urwyler H.; Charman W. N.; Matile H.; Wittlin S.; Charman S. A.; Vennerstrom J. L. Structure-activity relationship of the antimalarial ozonide artefenomel (OZ439). J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 2654–2668. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F.; Lin Z.; Wang F.; Zhao W.; Dong X. Four-membered heterocycles-containing 4-anilino-quinazoline derivatives as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 5385–5388. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J. L.; Kormos B. L.; Hayward M. M.; Coffman K. J.; Jasti J.; Kurumbail R. G.; Wager T. T.; Verhoest P. R.; Noell G. S.; Chen Y.; Needle E.; Berger Z.; Steyn S. J.; Houle C.; Hirst W. D.; Galatsis P. Discovery and preclinical profiling of 3-[4-(morpholin-4-yl)-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-5-yl]benzonitrile (PF-06447475), a highly potent, selective, brain penetrant, and in vivo active LRRK2 kinase inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 419–432. 10.1021/jm5014055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoren J. E.; Claffey M. M.; Snow S. L.; Reese M. R.; Arora G.; Butler C. R.; Boscoe B. P.; Chenard L.; DeNinno S. L.; Drozda S. E.; Duplantier A. J.; Moine L.; Rogers B. N.; Rong S.; Schuyten K.; Wright A. S.; Zhang L.; Serpa K. A.; Weber M. L.; Stolyar P.; Whisman T. L.; Baker K.; Tse K.; Clark A. J.; Rong H.; Mather R. J.; Lowe J. A. 3rd Discovery of a novel Kv7 channel opener as a treatment for epilepsy. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 4941–4944. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert H.; Mauser H.; Humm R.; Anselm L.; Kuehne H.; Hartmann G.; Gruener S.; Banner D. W.; Benz J.; Gsell B.; Kuglstatter A.; Stihle M.; Thoma R.; Sanchez R. A.; Iding H.; Wirz B.; Haap W. Identification of potent and selective cathepsin S inhibitors containing different central cyclic scaffolds. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 9789–9801. 10.1021/jm401528k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges T. R.; Abbott J. R.; Little A. J.; Sarkar D.; Salovich J. M.; Howes J. E.; Akan D. T.; Sai J.; Arnold A. L.; Browning C.; Burns M. C.; Sobolik T.; Sun Q.; Beesetty Y.; Coker J. A.; Scharn D.; Stadtmueller H.; Rossanese O. W.; Phan J.; Waterson A. G.; McConnell D. B.; Fesik S. W. Discovery and structure-based optimization of benzimidazole-derived ativators of SOS1-mdiated ncleotide echange on RAS. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 8875–8894. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryanoff B. E.; O’Neill J. C.; McComsey D. F.; Yabut S. C.; Luci D. K.; Jordan A. D. Jr.; Masucci J. A.; Jones W. J.; Abad M. C.; Gibbs A. C.; Petrounia I. Inhibitors of ketohexokinase: discovery of pyrimidinopyrimidines with specific substitution that complements the ATP-binding site. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 538–543. 10.1021/ml200070g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. J.; Johnson A. R.; Misner D. L.; Belmont L. D.; Castanedo G.; Choy R.; Coraggio M.; Dong L.; Eigenbrot C.; Erickson R.; Ghilardi N.; Hau J.; Katewa A.; Kohli P. B.; Lee W.; Lubach J. W.; McKenzie B. S.; Ortwine D. F.; Schutt L.; Tay S.; Wei B.; Reif K.; Liu L.; Wong H.; Young W. B. Discovery of GDC-0853: a potent, selective, and noncovalent Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase inhibitor in early clinical development. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2227–2245. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S. W.; Puentes L. N.; Wilson K.; Hsieh C. J.; Weng C. C.; Makvandi M.; Mach R. H. Examination of diazaspiro cores as piperazine bioisosteres in the olaparib framework shows reduced DNA damage and cytotoxicity. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5367–5379. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. S.; Birch A. M.; Brocklehurst K. J.; Broo A.; Brown H. S.; Butlin R. J.; Clarke D. S.; Davidsson O.; Ertan A.; Goldberg K.; Groombridge S. D.; Hudson J. A.; Laber D.; Leach A. G.; Macfaul P. A.; McKerrecher D.; Pickup A.; Schofield P.; Svensson P. H.; Sorme P.; Teague J. Use of small-molecule crystal structures to address solubility in a novel series of G protein coupled receptor 119 agonists: optimization of a lead and in vivo evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 5361–5379. 10.1021/jm300310c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S. W.; Griffin S.; Taylor M.; Sahlholm K.; Weng C. C.; Xu K.; Jacome D. A.; Luedtke R. R.; Mach R. H. Highly Selective Dopamine D3 Receptor Antagonists with Arylated Diazaspiro Alkane Cores. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 9905–9910. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebeneicher H.; Bauser M.; Buchmann B.; Heisler I.; Muller T.; Neuhaus R.; Rehwinkel H.; Telser J.; Zorn L. Identification of novel GLUT inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 1732–1737. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance N.; Gareau Y.; Guiral S.; Huang Z.; Isabel E.; Leclerc J. P.; Leger S.; Martins E.; Nadeau C.; Oballa R. M.; Ouellet S. G.; Powell D. A.; Ramtohul Y. K.; Tranmer G. K.; Trinh T.; Wang H.; Zhang L. Discovery of potent and liver-targeted stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) inhibitors in a bispyrrolidine series. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 980–984. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith J. M.; Jones W. M.; Pierce J. M.; Seierstad M.; Palmer J. A.; Webb M.; Karbarz M. J.; Scott B. P.; Wilson S. J.; Luo L.; Wennerholm M. L.; Chang L.; Brown S. M.; Rizzolio M.; Rynberg R.; Chaplan S. R.; Breitenbucher J. G. Heteroarylureas with spirocyclic diamine cores as inhibitors of fatty acid amide hydrolase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 737–741. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.12.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith J. M.; Apodaca R.; Tichenor M.; Xiao W.; Jones W.; Pierce J.; Seierstad M.; Palmer J.; Webb M.; Karbarz M.; Scott B.; Wilson S.; Luo L.; Wennerholm M.; Chang L.; Brown S.; Rizzolio M.; Rynberg R.; Chaplan S.; Breitenbucher J. G. Aryl piperazinyl ureas as inhibitors of Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase (FAAH) in rat, dog, and primate. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 823–827. 10.1021/ml300186g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnes J. G.; Gero T.; Huang S.; Diebold R. B.; Ogoe C.; Grover P. T.; Su M.; Mukherjee P.; Saeh J. C.; MacIntyre T.; Repik G.; Dillman K.; Byth K.; Russell D. J.; Ioannidis S. Towards the next generation of dual Bcl-2/Bcl-xL inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 3026–3033. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Lu H.; Xu Z.; Luan L.; Li C.; Xu Y.; Dong K.; Zhang J.; Li X.; Li Y.; Liu G.; Gong S.; Zhao Y. G.; Liu A.; Zhang Y.; Zhang W.; Cai X.; Xiang J. N.; Elliott J. D.; Lin X. Discovery of CNS Penetrant CXCR2 antagonists for the potential treatment of CNS demyelinating disorders. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 397–402. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiteau J. G.; Ouvry G.; Arlabosse J. M.; Astri S.; Beillard A.; Bhurruth-Alcor Y.; Bonnary L.; Bouix-Peter C.; Bouquet K.; Bourotte M.; Cardinaud I.; Comino C.; Deprez B.; Duvert D.; Feret A.; Hacini-Rachinel F.; Harris C. S.; Luzy A. P.; Mathieu A.; Millois C.; Orsini N.; Pascau J.; Pinto A.; Piwnica D.; Polge G.; Reitz A.; Reverse K.; Rodeville N.; Rossio P.; Spiesse D.; Tabet S.; Taquet N.; Tomas L.; Vial E.; Hennequin L. F. Discovery and process development of a novel TACE inhibitor for the topical treatment of psoriasis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 945–956. 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blizzard T. A.; DiNinno F.; Morgan J. D. 2nd; Chen H. Y.; Wu J. Y.; Gude C.; Kim S.; Chan W.; Birzin E. T.; Tien Yang Y.; Pai L. Y.; Zhang Z.; Hayes E. C.; DaSilva C. A.; Tang W.; Rohrer S. P.; Schaeffer J. M.; Hammond M. L. Estrogen receptor ligands. Part 7: Dihydrobenzoxathiin SERAMs with bicyclic amine side chains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 3861–3864. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felts A. S.; Rodriguez A. L.; Smith K. A.; Engers J. L.; Morrison R. D.; Byers F. W.; Blobaum A. L.; Locuson C. W.; Chang S.; Venable D. F.; Niswender C. M.; Daniels J. S.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W.; Emmitte K. A. Design of 4-oxo-1-aryl-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamides as selective negative allosteric modulators of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor subtype 2. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 9027–9040. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.