Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus infections represent the major cause of titanium based-orthopaedic implant failure. Current treatments for S. aureus infections involve the systemic delivery of antibiotics and additional surgeries, increasing health-care costs and affecting patient’s quality of life. As a step toward the development of new strategies that can prevent these infections, we build upon previous work demonstrating that the colonization of catheters by the fungal pathogen Candida albicans can be prevented by coating them with thin polymer multilayers composed of chitosan (CH) and hyaluronic acid (HA) designed to release a β-amino acid-based peptidomimetic of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). We demonstrate here that this β-peptide is also potent against S. aureus (MBPC = 4 µg/mL) and characterize its selectivity toward S. aureus biofilms. We demonstrate further that β-peptide-containing CH/HA thin-films can be fabricated on the surfaces of rough planar titanium substrates in ways that allow mammalian cell attachment and permit the long-term release of β-peptide. β-Peptide loading on CH/HA thin-films was then adjusted to achieve release of β-peptide quantities that selectively prevent S. aureus biofilms on titanium substrates in vitro for up to 24 days and remained antimicrobial after being challenged sequentially five times with S. aureus inocula, while causing no significant MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cytotoxicity compared to uncoated and film-coated controls lacking β-peptide. We conclude that these β-peptide-containing films offer a novel and promising localized delivery approach for preventing orthopaedic implant infections. The facile fabrication and loading of β-peptide-containing films reported here provides opportunities for coating other medical devices prone to biofilm-associated infections.

Keywords: Biofilms, Antimicrobial β-peptides, S. aureus, Polyelectrolyte multilayers, Titanium substrates

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Orthopaedic implants are used routinely for the fixation of bone fractures, replacement of arthritic joints, correction and stabilization of the spinal column, and other orthopaedic applications [1]. Titanium and titanium alloys are considered the gold-standard material for orthopaedic implants due to their high mechanical stability, low susceptibility to corrosion, inertness, biocompatibility and long-term functionality [1–4]. While the surface topography of titanium is beneficial in the context of promoting osseointegration of the implant, it also promotes microbial colonization [5]. Post-operative microbial infections can occur either within the first two months after implantation and/or many months to years post-surgery and are one of the most common complications following an orthopaedic device implantation, with infection rates of 1–2.5% for primary knee and hip replacements and up to 20% after revision surgeries have been performed [4,6,7]. Post-operative infections have been linked to septic loosening, implant failure, and, in severe cases, morbidity or mortality [3,6,8–15].

Staphylococci, including Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), and coagulase-negative Staphylococci, are the most common isolated microorganisms from infected orthopaedic implants due to their ability to adhere to implants surfaces and subsequently form biofilms on implants [16,17]. These biofilms can then result in septic arthritis and osteomyelitis [3,7,12,18–20]. Current treatments for S. aureus orthopaedic device-associated infections consist of the systemic delivery of antibiotics in combination with surgical site radical debridement and/or implant replacements; several revision surgeries are often needed [6,12,14,21,22]. In addition to the severe side effects associated with the systemic delivery of antibiotics, treatment for orthopaedic device-associated infections faces challenges such as poor antibiotic bioavailability in bone tissue and antibiotic resistance in bacterial biofilms [12,14,21,22]. In view of these challenges, there is a critical need for the development of new strategies preventing microbial infections associated with orthopaedic implants.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and peptidomimetic analogs of AMPs have been studied as potential new classes of antimicrobials. These AMPs are part of the host’s adaptive immune system and often display selective toxicity to microbial cells vs. host cells [23,24]. Structural characteristics such as an overall net positive charge and adopting a global amphiphilic conformation (e.g., α-helix) upon contact with microbial surfaces confer antimicrobial activity [25,26]. The proposed toxicity mechanism of many types of AMPs involves disruption of the microbial cell membrane, leading to membrane permeabilization, cell lysis and subsequent death [23,27]. Given the lack of a single target of AMPs, the development of bacterial resistance to AMPs and their mimetics is thought to be less likely than for traditional antibiotics [24,28].

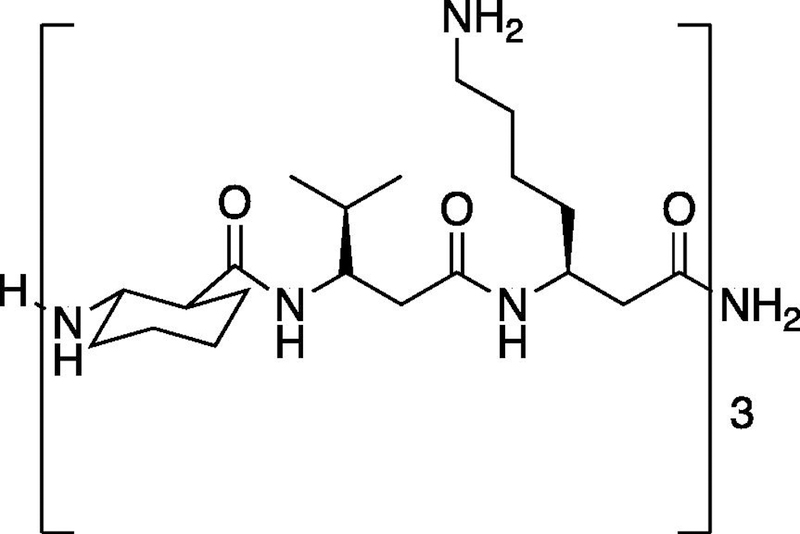

While AMPs hold promise as antimicrobials, their structural instability under physiologic conditions and susceptibility to protease degradation in vivo have limited their development as antimicrobials [29–32]. Recently, β-peptide foldamers have emerged as cationic, globally amphiphilic structurally stable peptidomimetics. β-Peptides have been demonstrated to have strong antibacterial activity against planktonic Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [26,27,33–37]. Motivated by the potential of β-peptides as an alternative antimicrobial treatment, we have previously demonstrated 14-helical β-peptide toxicity toward planktonic Candida albicans (C. albicans) cells and prevention of C. albicans biofilms in vitro [26,35,38,39]. Our previous work also identified the (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 β-peptide (Scheme 1) as a promising antimicrobial candidate due to its strong activity against planktonic C. albicans cells (MIC = 4 µg/mL), ability to prevent C. albicans biofilm formation (MBPC = 8 µg/ml) and good selectivity to microbial cells (2.3 ± 0.7% hemolysis at planktonic MIC) [35,38]. Here we build upon our previous work to evaluate the ability of (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 β-peptide to inhibit the formation of S. aureus biofilms and selectivity to S. aureus vs. preosteoblast cells

Scheme 1.

Chemical structure of β-peptide (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3.

In an effort to improve the selectivity of AMPs and AMP mimetics, increase activity against microbial cells and reduce the toxicity associated with a systemic delivery, strategies that can localize their delivery to sites prone to infection have recently emerged as an alternative treatment for orthopaedic device-related infections. Polyelectrolyte multilayer (PEM) coatings have been developed as a localized platform for surface-mediated release of active biological agents such as growth factors (e.g., BMP-2, bFGF), β-peptides, antibiotics and DNA [22,40–43]. We have also recently reported the prevention of C. albicans colonization and biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo on catheters coated with either polyglutamic acid / poly-L-lysine (PGA/PLL) or chitosan /hyaluronic acid (CH/HA) PEM films loaded with β-peptide [41,44,45]. Motivated by that past work, we focus here on demonstrating the potential use of β-peptide-containing PEM coatings fabricated on the surfaces of rough titanium surfaces for preventing S. aureus-related infections. We further evaluated the biocompatibility of these coatings with model osteogenic mammalian cells (MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast). Our results suggest that the controlled release of β-peptide quantities selective only to microbial cells can be achieved using minor modifications, such as chemical crosslinking and by tuning the β-peptide loading. Specifically, our results reveal that β-peptide-containing films fabricated on rough titanium substrate surfaces can release sufficient quantities of β-peptide to prevent S. aureus biofilm formation in vitro for up to 24 days and five bacterial challenges. Overall, the results reported here indicate β-peptide-containing PEMs coatings to be a useful platform for the design of antibacterial coated orthopaedic devices for inhibiting S. aureus biofilm formation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Branched polyethyleneimine (BPEI, MW=25,000), chitosan (CH, medium molecular weight), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), paraformaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, menadione, filtered water for cell culture, fluorescein-labeled hyaluronic acid, chloramphenicol, and medical grade titanium disks were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium hyaluronate (HA, MW 1,5000,000–2,200,000) was purchased from Acros Organic. 2,3-Bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT), RPMI 1640 powder containing L-glutamine and phenol red (without HEPES or Na bicarbonate), penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/mL), NaCl, 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (Sulfo-NHS), Calcein-AM, ethidium homodimer-1, Hoechst 33342, Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ II Chamber Slide™ System, and Pierce™ Quantitative Fluorometric Peptide Assay were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. α-MEM (1x) minus ascorbic acid was obtained from Gibco. Osmium tetroxide (4%) was obtained from Electron Microscopy Sciences. Accutase was purchased from Innovative Cell Technologies. Cell Titer Glo 2.0 assay kits were obtained from Promega. All materials were used as received.

2.2. General Considerations

β-Peptide (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 was synthesized using previously reported methods [35]. Titanium substrates were cut to 0.6 cm width x 1.8 cm length dimensions, cleaned with acetone, ethanol, methanol, and deionized water, dried under a stream of filtered and compressed air, and plasma etched for 1800s (Plasma Etch, Carson City, NV) prior to the fabrication of PEM films. Uncoated, film-coated and β-peptide-loaded titanium substrates were UV sterilized for 15 min per side using a biosafety cabinet prior to biological experiments. Fluorescence microscopy images were obtained with an Olympus IX70 epifluorescence microscope using Nikon NIS image acquisition software. Fiji Image J was used to create merged images and quantify fluorescence intensities. Critical point drying, sputtering and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were performed using a Leica EM CPD 300 critical point dryer, Leica ACE600 Sputter, and a LEO SEM microscope at 5kV. Fluorescence measurements to characterize β-peptide release, absorbance measurements to quantify S. aureus cell viability, and luminescence measurements to quantify MC3T3-E1 cell viability were taken with a Tecan M200 multi-well plate reader.

2.3. Characterization of β-peptide antimicrobial minimal biofilm prevention concentration (MPBC)

The antimicrobial activity of (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 β-peptide against preventing S. aureus biofilms was assayed in 96-well plates according to susceptibility testing guidelines provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [46]. S. aureus ATCC 3359 cells were grown overnight at 37°C in liquid TSB, subcultured the following day, and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4. An aliquot of 100 µL of two-fold serial dilutions of β-peptide in MH medium + 0.5% glucose was mixed with 100 µL of S. aureus (106 CFU/mL) cell suspension and the plates were incubated for 24 hr at 37°C to allow biofilm formation. Wells lacking β-peptide and wells lacking cells and β-peptide were included as controls. After 24 hr, non-adherent cells were removed by pouring the supernatant. Biofilms were washed two times with PBS, and resulting biofilms were assayed as previously reported using an XTT assay [35,38]. The cell viability was normalized to the untreated control and plotted as a function of β-peptide concentration. The lowest assayed concentration of β-peptide that resulted in a decrease in absorbance of at least 99% of the mean was determined to be the minimal biofilm prevention concentration (MBPC) of the peptide.

2.4. Characterization of β-peptide toxicity against MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells

MC3T3-E1 cell toxicity was assessed using the Cell Titer Glo protocol to quantify the amount of ATP present in metabolically active cells. MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in MEMα medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% of penicillin-streptomycin, in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. Upon reaching 100% confluency, cells were detached using Accutase, centrifuged and resuspended in MEMα medium to a final concentration of 5 × 104 cells/cm2. An aliquot of 100 µL of two-fold serial dilutions of β-peptide in MEMα medium was mixed with 100 µL of the MC3T3-E1 cell suspension and the plates were incubated for 24 hr at 37°C and 5% CO2 in air. Wells lacking β-peptide and wells lacking cells and β-peptide were included as controls. Afterwards, Cell Titer Glo reagent (100 µL) was added into each well, incubated for 5 min, and the luminescence signal was recorded. The percent of cell death in each well was calculated as:

| (1) |

where RLUcontrol represents the luminescence signal of untreated control (well lacking β-peptide) and RLUpeptide represents the luminescence signal of β-peptide-containing samples. The percent of cell death was plotted as a function of β-peptide concentration to generate the dose-response curve for MC3T3-E1 toxicity. The IC20 value was determined as the β-peptide concentration that resulted in 20% death of MC3T3-E1 cells.

2.5. Fabrication of polyelectrolyte multilayers films on the surfaces of titanium substrates

Solutions of HA and BPEI (1 mg/mL) were prepared in 0.15 M NaCl deionized water. CH solution (1 mg/mL) was prepared in 0.1 M acetic acid and 0.15 M NaCl deionized water. PEMs were fabricated using the following general protocol: substrates were (1) submerged in BPEI solution for 30 min, (2) rinsed twice in 0.15 M NaCl deionized water for 1 min each, (3) immersed in the CH solution for 5 min, (4) rinsed as described in step 2, (5) immersed in the HA solution for 5 min, (6) rinsed as described in step 2 and steps 3–6 were repeated until a total of 19.5 bilayers were deposited. For experiments designed to characterize film growth profiles, PEMs were fabricated as described above but using fluorescein-labeled hyaluronic acid. Fluorescence images from 3 different regions of the PEM-coated titanium substrate were taken after 4.5, 9.5, 14.5 and 19.5 bilayers were deposited.

2.6. Chemical crosslinking of PEM films deposited on titanium substrates and characterization using PM-IRRAS

CH/HA PEMs films were chemically crosslinked by immersing PEM-coated titanium substrates in a 400 mM EDC/100 mM Sulfo-NHS solution in 0.15 M NaCl deionized water for 16 hr at room temperature. Next, substrates were rinsed 3 times for 30 min each, followed by drying. For epifluorescence microcopy to characterize the films before and after crosslinking, CH/HA films were fabricated using fluorescein-labeled HA and fluorescence images were taken before and after crosslinking. An uncrosslinked coated substrate immersed in 0.15 M NaCl for 16 hr was used as control. To characterize CH/HA PEM film crosslinking using polarization-modulation infrared reflectance-absorbance spectroscopy (PM-IRRAS), CH/HA PEMs films were deposited on gold-coated silicon substrates and crosslinked as described above. PM-IRRAS was conducted in a similar fashion to previously reported methods [47].

2.7. PEM loading with β peptide

Titanium substrates coated with crosslinked CH/HA PEMs were immersed in a 0.44 mg/mL solution (or an otherwise desired concentration) of β-peptide (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 in 0.15 M NaCl deionized water for a period of 24 hr at room temperature. β-Peptide loaded substrates were removed from solution and dried. Uncoated and PEM film-coated controls were immersed in 0.15 M NaCl deionized water without β-peptide for 24 hr.

2.8. Estimation of film thickness

The thicknesses of CH/HA, crosslinked CH/HA, and β-peptide-loaded CH/HA films on titanium substrates were estimated using focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM). β-Peptide loaded CH/HA films were prepared as described before. Uncrosslinked CH/HA films were incubated for a total of 30 hr in 0.15 M NaCl deionized water as a control lacking crosslinking solution and β-peptide. Similarly, control crosslinked CH/HA films were incubated in 0.15 M NaCl deionized water and lacking β-peptide for 24 hr. Samples were platinum-palladium coated and 1 rectangular section 10 µm wide was milled using a 0.10 nA electrical current to create a film cross-section. Five different regions within the milled section were selected to estimate the film thickness using SEM at 2kV.

2.9. Characterization β-peptide release from PEM films

Characterization of β-peptide release from PEMs on titanium substrates was performed by following the manufacturer’s specifications for the Pierce™ Quantitative Fluorometric Peptide Assay kit. Briefly, uncoated, film-coated, and β-peptide loaded titanium substrates were immersed in 750 µL of filtered water and incubated at 37°C. At predetermined intervals, titanium substrates were removed from the incubator and β-peptide concentration in the release solution was estimated. After each measurement, titanium substrates were immersed in 750 µL of fresh filtered water and returned to the incubator. The plot shown in Figure 4 was constructed by cumulatively adding the concentrations of β-peptide released at each timepoint and is normalized to the titanium substrate surface area.

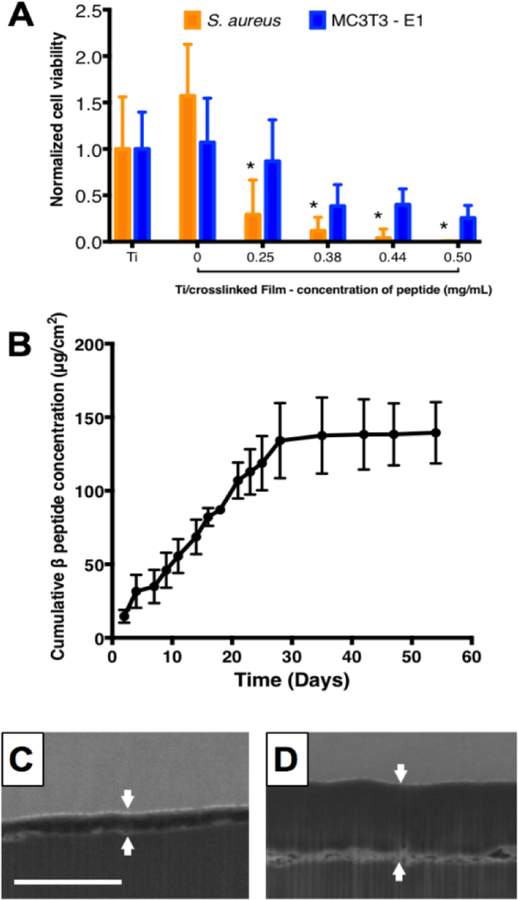

Figure 4:

β-peptide loading and release from titanium substrates coated with crosslinked CH/HA films. 19.5 bilayer thick CH/HA films were deposited and crosslinked for 16 hr using an EDC/NHS solution in 0.15M NaCl deionized water. Incorporation of β-peptide was performed by incubating the films for 24 hr in a β-peptide solution in deionized water containing 0.15M NaCl. A) Quantification of S. aureus and MC3T3-E1 cell viability on β-peptide loaded CH/HA films as a function of β-peptide loading concentration. After CH/HA film fabrication and β-peptide loading, S. aureus or MC3T3-E1 cells were inoculated on the films and allowed to grow for 24 hr. Viabilities were quantified using XTT and Cell Titer Glo assays, respectively. B) Plot showing the cumulative release of β-peptide into PBS (750 µL) at 37 °C as a function of time. β-Peptide release concentrations were quantified by using the Pierce quantitative fluorometric assay, calibrated with a standard curve generated with known β-peptide concentrations. C-D) Representative FIB-SEM images of PEM film cross-sections C) before and D) after β-peptide loading. White arrows denote the film edges. Scale bar: 3µm. Data points represent the mean values and error bars are the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

2.10. Characterization of the antibacterial activity of β-peptide-loaded PEM films

S. aureus ATCC 3359 and AH17456 cells were grown overnight as described above. TSB growth medium for the GFP-expressing AH1756 strain was supplemented with 10 µg/mL chloramphenicol for plasmid maintenance purposes. Cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in MH medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose to a cell density of 106 CFU/mL. Uncoated, film-coated, and β-peptide loaded substrates were placed inside a four-well Lab Tek chamber containing 750 µL of S. aureus cell suspension and incubated for 24 hr at 37°C. Biofilms were characterized using (i) an XTT metabolic activity assay and (ii) by imaging the biofilms using fluorescence microscopy and SEM.

For the XTT metabolic activity assay, each titanium substrate was removed from the four-well Lab Tek chamber, gently washed with PBS and transferred into a new and unused Lab Tek chamber. XTT solution (750 µL; 0.5 g/L in PBS, supplemented with 3 µM menadione in acetone) was added to each well of the Lab Tek Chamber containing the uncoated, film-coated and β-peptide loaded titanium substrates. After incubating the XTT solution at 37°C for 1.5 hr in the dark, 75 µL of the supernatant was transferred into a 96-well plate and the absorbance of the solution at 490 nm was measured to determine the relative metabolic activity of the biofilms. Data were plotted relative to the absorbance value from the well containing the uncoated titanium substrate control.

A biological and XTT metabolic activity assay configuration similar to that described above was used to evaluate biofilm formation after multiple S. aureus challenge experiments and after incubation of substrates in PBS prior to biofilm formation. For the multiple challenge experiments, uncoated, film-coated, and β-peptide loaded titanium substrates were initially incubated with an S. aureus inoculum (106 CFU/mL) and biofilms were allowed to grow for 24 hr (challenge 1). Substrates were then incubated in PBS for an additional 2 days and subsequently challenged with an additional S. aureus inoculum (106 CFU/mL) for 24 hr (challenge 2). This multiple-challenge process was repeated until 5 different S. aureus challenges were achieved, for a total of 18 days. For the PBS pre-incubation experiments, uncoated, film-coated, and β-peptide loaded titanium substrates were incubated in PBS at 37°C for the specified period of time (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 days) and then challenged with an S. aureus inoculum (106 CFU/mL). Extents of biofilm formation were quantified via XTT assay and data were normalized to the uncoated control.

To analyze biofilm formation using fluorescence microscopy, a GFP-expressing S. aureus strain AH1756 was used. Following 24 hr biofilm formation at 37°C, uncoated, film-coated, and β-peptide loaded titanium substrates were washed with PBS and biofilm growth was inspected under an epifluorescence microscope. We also evaluated S. aureus biofilm morphology using SEM. For this analysis, uncoated, film-coated, and β-peptide loaded titanium substrates were prepared using a previously published protocol [41,44]. Specimens were mounted in aluminum stubs and sputter-coated with a 12 nm thick layer of platinum-palladium before being imaged by SEM.

2.11. Biocompatibility of β-peptide-loaded PEM films

Uncoated, film-coated, and β-peptide-loaded titanium substrates were placed inside four-well Lab Tek chambers containing 750 µL of an MC3T3-E1 cell suspension adjusted to a cell density of 5×104 cells/cm2 in α-MEM and incubated for 24 hr at 37°C and 5% CO2. MC3T3-E1 cell viability was characterized using (i) a Cell Titer Glo metabolic activity assay, (ii) by visualizing MC3T3-E1 cell attachment with fluorescence microscopy and (iii) by quantifying the percent proliferative cells.

Cell Titer Glo assessment of MC3T3-E1 cell metabolic activity was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations using a reagent volume of 750 µL. Next, 180 µL of supernatant was transferred into a 96-well plate and luminescence signal was quantified. Background luminescence from wells containing medium and Cell Titer Glo was subtracted from all readings and data were normalized relative to the uncoated titanium control. For the PBS pre-incubation experiments, a similar experimental approach as described above was used. MC3T3-E1 viability after 24 hr was quantified using the Cell Titer Glo assay and proliferative cells were identified using Ki67 staining as previously described [48]. The percent of Ki67 positive cells was quantified by counting Ki67 positive cells relative to the total cells, stained with Hoechst (2 µg/mL), adhered on three different regions per substrate. MC3T3-E1 cells from immunofluorescence images of three independent experiments including three technical replicates each were manually counted using Fiji Image J software. For visualizing MC3T3-E1 cell attachment, fluorescence microscopy images of MC3T3-E1 cells on the surfaces of uncoated, film-coated, and β-peptide-loaded titanium substrates were acquired as previously described [22].

2.12. Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc) was used for all statistical analysis. For pairwise comparisons a Student’s T-test was performed. Statistical comparisons were performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or one-way ANOVA as appropriate, with Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference post-hoc analysis for multiple testing over all comparisons. Figure legends describe the statistical tests used for each particular data set. Statistical significance was accepted at a p value of less than 0.05. Data are represented as mean values ± standard deviations (SD) for three separate biological replicates, with three technical replicates in each biological replicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. β-peptide inhibits S. aureus biofilm formation

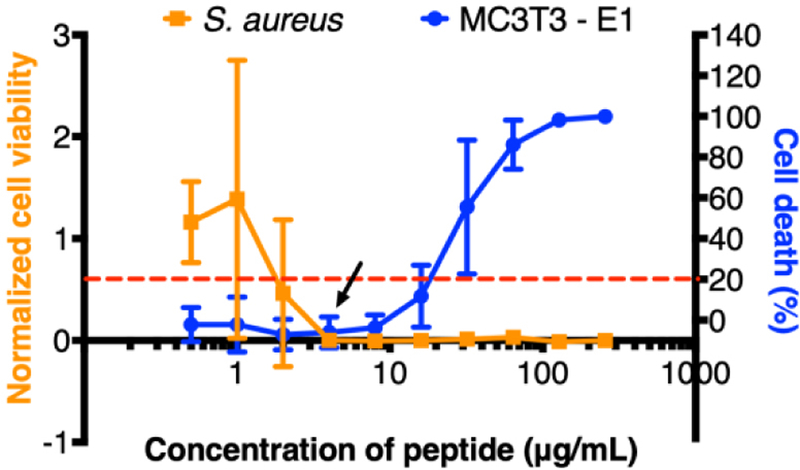

The ability of S. aureus cells to attach and form drug-resistant biofilms on the surfaces of orthopaedic devices poses a challenge for the treatment of implant-related bacterial infections. Motivated by previous studies demonstrating the broad spectrum antibacterial activity of cationic 14-helical β-peptides against Gram positive and Gram negative bacterial species [34,49,50], their strong activity against planktonic S. aureus cells with MICs ranging from 3.1 to 200 µg/mL [27,33,51], and previous work demonstrating (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 β-peptide activity and selectivity against C. albicans cells vs. human red blood cells [35,38], we tested the potential of the (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 β-peptide to prevent the formation of S. aureus biofilms. We quantified the MBPC for preventing S. aureus biofilms in 96-well polystyrene plates, following the CLSI antimicrobial susceptibility standards [46], with modifications to include biofilm growth (e.g. 37°C, MH medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose and 24 hr incubation time). Results shown in Figure 1 (orange squares) show that (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 β-peptide has an MBPC of 4 μg/mL. Although strong antimicrobial activity is highly desired, evaluating selectivity to S. aureus cells exclusively is also crucial for potential use to prevent orthopaedic devices-related infections in vivo. We therefore, investigated (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 β-peptide biocompatibility with MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast subclone 4 cells, a model mammalian cell line with osteoblast differentiation capacity and mineralization activity. Our results showed a concentration-dependent β-peptide toxicity toward MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells with an inhibitory concentration resulting in 20% cell death (IC20) of 22.6 ± 7.4 μg/mL (Figure 1, blue circles). We defined an in vitro selectivity index (SI) as the ratio of β-peptide cytotoxicity (IC20) against MC3T3-E1 cells to MBPC against inhibiting S. aureus biofilm formation (SI= IC20/MBPC). Using this approach, (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 β-peptide was demonstrated to have a SI value of 5.7, suggesting good selectivity for S. aureus vs. MC3T3-E1 cells. This result motivated the development of delivery strategies for its localized release for preventing S. aureus biofilm formation.

Figure 1:

Effect of β-peptide concentration on inhibition of S. aureus biofilms and toxicity toward MC3T3-E1 cells. S. aureus cells (106 cells/mL) were incubated with the indicated β-peptide concentrations in MH + 0.5% glucose media in 96-well plates for 24 hr at 37 °C, and then biofilm was quantified using an XTT assay. Biofilm viability was normalized to a control lacking β-peptide. The arrow indicates the MIC for inhibiting S. aureus biofilm formation. To evaluate β-peptide cytotoxicity, we incubated MC3T3-E1cells (5×104 cells/cm2) with the indicated β-peptide concentrations in MEM α medium in 96-well plates for 24 hr at 37 °C and 5% CO2. MC3T3-E1 cell viability was quantified using a Cell Titer Glo assay. Cell death was calculated based on the percent change with respect to the cells grown in the absence of peptide. The dashed red line indicates the IC20 β-peptide concentration. Data points represent the mean values and error bars the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

3.2. Fabrication and characterization of β-peptide-containing PEM films

We selected the polysaccharide-based CH/HA PEM film system for use in this study because these coatings have been well-studied as a platform for the localized release of active agents from antimicrobial coatings and tissue-integrating scaffolds [41,52–56]. Additionally we have recently demonstrated antifungal activity of CH/HA PEMs containing β-peptide [41,45]. That study showed that CH/HA PEM films containing (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 fabricated in the lumens of catheter segments using an iterative flow-based approach prevented C. albicans biofilms in vitro and in vivo. This current study sought to extend upon that prior work to (i) determine whether CH/HA PEMs fabricated on rough and planar titanium substrates could be used to promote the long-term release of β-peptide and prevent formation of S. aureus-related biofilms, (ii) evaluate the biocompatibility of β-peptide-loaded PEM films with the MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cell line, and (iii) assess the selectivity of these β-peptide-containing coatings against S. aureus vs. MC3T3-E1 cells.

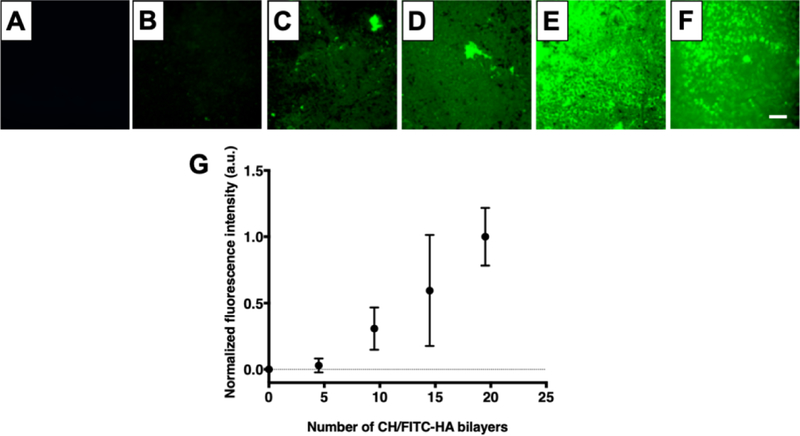

Using an iterative immersion-based layer-by-layer assembly approach, we deposited CH/HA multilayers on the surfaces of titanium substrates (Figure 2) and characterized their growth by monitoring the fluorescence intensity of FITC-labeled HA incorporated within the films, using a previously published approach consisting of imaging and analyzing the fluorescence intensity after the deposition of every five CH/HA bilayers [44]. As shown in Figure 2, the average fluorescence intensity increased with the number of CH/HA bilayers deposited, consistent with layer-by-layer film growth [57].

Figure 2:

CH/HA film deposition on titanium substrates. A–E) Representative epifluorescence images of (CH/FITC-HA)x coated titanium substrates; where x= 0 (A), 4.5 (B), 9.5 (C), 14.5 (D), 19.5 (E). (F) Representative epifluorescence image of (CH/FITC-HA)19.5 film deposited on titanium after EDC/NHS cross-linking. G) Growth profile of crosslinked CH/HA films. Fluorescence intensity was quantified using Fiji Image J. Data points are the average mean values and error bars are the standard deviation of at least three regions of each titanium substrate corresponding to three independent experiments, normalized to the fluorescence intensity of 19.5 CH/FITC-HA bilayers. Scale bar: 260 µm.

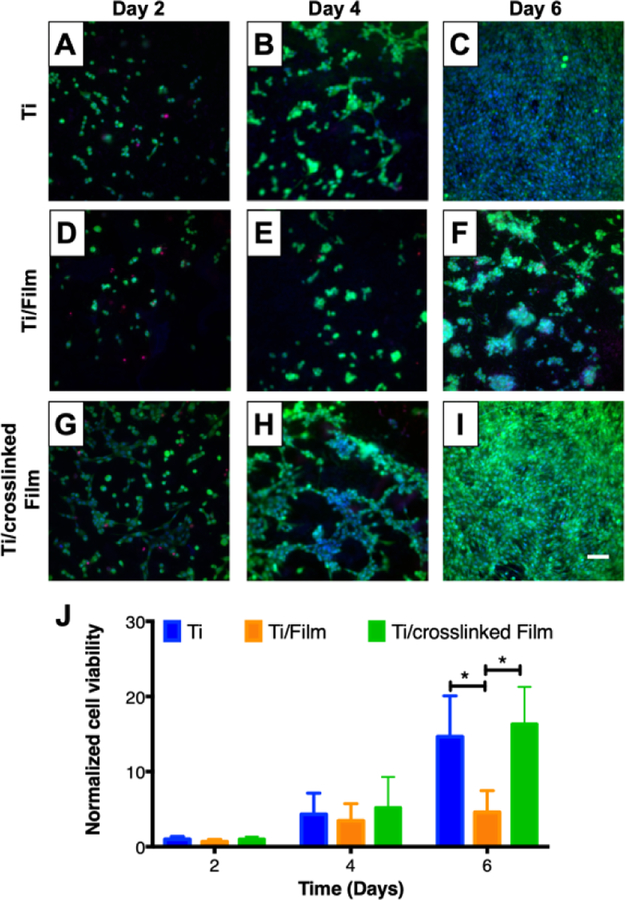

We then characterized the ability of MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells to attach and proliferate on CH/HA film-coated titanium substrates over a period of 6 days. Visual inspection of cell attachment and quantification of proliferation with a Cell Titer Glo assay revealed the extent of MC3T3-E1 cells attachment on CH/HA film-coated titanium substrates (Figure 3 D–F, S4) was not different than on uncoated titanium (Figure 3 A–C, S4). However, proliferation over a period of 6 days on CH/HA film-coated titanium substrates (Figure 3 D–F, I, orange bars) was lower than on uncoated titanium (Figure 3 A–C, I, blue bars), suggesting that the surfaces of the film-coated substrates were less favorable for supporting MC3T3-E1 cell growth than bare titanium. These results are in accordance with previous studies [54] and are in accordance with additional literature that demonstrate cellular adhesion and proliferation on PEM-coated surfaces is dependent upon film physical and mechanical properties (e.g. Young’s modulus, roughness, and degree of hydration) [56–58]. For example, previous studies have demonstrated that depositing poly(allylamine hydrochloride – poly(acrylic acid) films at a higher pH resulted in more rigid films that increased the adhesion of NR6WT fibroblasts [59]. In addition, Schneider et. al. demonstrated that chemical crosslinking of CH/HA films increased film roughness and rigidity and enhanced the viability of attached HT29 cells [60].

Figure 3:

MC3T3-E1 cell attachment and proliferation on titanium substrates coated with 19.5 bilayer thick CH/HA films. A–I) Fluorescent micrographs of live cells (Calcein AM, green), dead cells (propidium iodide, red) and nuclei (Hoechst, blue) of representative fields of (A–C) uncoated, (D–F) CH/HA film-coated and (G–I) crosslinked CH/HA film-coated titanium substrates at day 2 (A, D, and G), day 4 (B, E, and H) and day 6 (C, F, and I). Scale bar: 175 µm. J) Plot showing quantification of MC3T3-E1 cell viability using the Cell Titer Glo assay as a function of time after seeding on uncoated, CH/HA film-coated, and crosslinked CH/HA film-coated titanium substrates. MC3T3-E1 cell viability is normalized to results obtained using an uncoated control. Data points represent the mean values and error bars are the standard deviation of three independent experiments. Asterisks (*) indicate p < 0.01 by two-Way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

As part of a strategy to improve MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation on our CH/HA films we chemically crosslinked the films using an EDC/NHS (400 mM EDC/100 mM NHS in 0.15 M NaCl) carbodiimide treatment in a post-fabrication step [61–63]. This carbodiimide-based crosslinking catalyzes the formation of amide bonds between the carboxylic groups of HA and the amine groups of CH, and was selected because both crosslinking agents are water soluble and carbodiimides do not remain as part of the amide linkage, but instead are converted to nontoxic, water soluble urea derivatives that can be easily removed [64,65]. Following the crosslinking of CH/HA films containing FITC-labeled HA, we characterized the films by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 2 E–F). We also included CH/HA films incubated in deionized water containing 0.15 M NaCl during the crosslinking step as an uncrosslinked control (Figure S2). Our results demonstrate that, after crosslinking, the surface remained covered by the films (Figure 2F, S2B), similar to control CH/FITC-HA films that were incubated in deionized water containing 0.15 M NaCl (Figure S2C). We confirmed CH/HA film crosslinking using polarization modulation infrared reflection-absorption spectroscopy (PM-IRRAS). Because PM-IRRAS requires a reflective surface, we deposited the CH/HA PEMs on gold-coated silicon wafers and obtained the infrared spectra of the films before and after EDC/NHS crosslinking. Inspection of the spectra revealed disappearance of the HA carbonyl group at 1412 cm-1 after film crosslinking (Figure S3), consistent with the formation of an amide bond between CH and HA. Additionally, we observed that the crosslinked films had a strong absorbance in the amide I (1660 cm−1) and amide II bands (1570 cm−1), further suggesting the successful crosslinking of the CH/HA films (Figure S3). We then compared MC3T3-E1 cell adhesion and proliferation on crosslinked and uncrosslinked films. We did not observe a significant change in MC3T3-E1 cell adhesion on the surfaces of the uncoated substrates, uncrosslinked films, and crosslinked films (Figure 3 and S4). However, CH/HA film crosslinking enhanced cell MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation over 6 days compared to uncrosslinked films, leading to a similar number of cells as the bare titanium surface (Figure 3), suggesting that film crosslinking leads to coatings that can support MC3T3-E1 cell viability and proliferation. These results are in accordance with previous studies suggesting that uncrosslinked CH/HA films behave as a “gel-like” substrates causing low adhesion of mammalian cells due to their low stiffness [57] and that increasing PEM film rigidity can enhance cell attachment and proliferation [58]. In order to increase PEM mechanical properties, fabrication conditions can be varied, including modulating film thickness, pH during assembly, and post-fabrication crosslinking. Boudou et.al. reported that EDC crosslinking significantly increased the Young’s modulus of CH/HA films [56]. Schneider et al. demonstrated that CH/HA crosslinking improved the attachment of human colonic adenocarcinoma (HT29) cells [60]. Therefore, we attribute the increased MC3T3-E1 cell viability and proliferation observed following chemical crosslinking to the CH/HA films to changes in film rigidity, roughness, and/or degree of hydration as demonstrated in past studies [56–58,60].

Following the fabrication of crosslinked CH/HA films on titanium substrates, β-peptide (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 was loaded into the films by incubating the films in a 0.15 M NaCl solution containing the β-peptide [41,44,45]. For selective bacterial biofilm prevention without toxicity to mammalian cells, β-peptide must elute to achieve a local concentration toxic to S. aureus but nontoxic to MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells. Therefore, we investigated the effects of varying the concentration of β-peptide in the loading solution on S. aureus and MC3T3-E1 cell viability after being cultured for 24 hr on uncoated titanium, on film-coated substrates lacking β-peptide, and on film-coated substrates loaded with β-peptide (Figure 4A). This approach of reporting β-peptide loading concentration was used due to difficulties associated with accurately quantifying the amount of β-peptide loaded into the films (e.g. by post-loading extraction). Past studies from our group have shown that varying β-peptide concentration in the loading solution leads to consistent and measurable differences in both the amount of β-peptide loaded and the release profiles of β-peptide from the films [41,44,66]. Our results demonstrate that the extents of S. aureus biofilm inhibition and toxicity toward MC3T3-E1 cells were dependent upon the concentration of β-peptide in the loading solution (Figure 4A). A β-peptide loading solution concentration of 0.44 mg/mL lead to coatings that completely inhibited S. aureus biofilm formation and maintained at least 50% survival of MC3T3-E1 cells at 24 hr (Figure 4A). Thus, this loading concentration was selected for further characterization of antimicrobial activity and biocompatibility of β-peptide-containing films.

We next investigated the kinetics of β-peptide release from crosslinked CH/HA films on titanium substrates by incubating uncoated titanium, films lacking β-peptide, and films loaded with β-peptide in deionized water for predetermined amounts of time. Figure 4B shows the cumulative release profile of β-peptide (ACHC-β3hVal-β3hLys)3 from crosslinked films over a period of 54 days. Our results reveal that β-peptide is released gradually at a constant rate of 4.6 ± 2.2 µg/cm2/day over a period of 28 days. Over this period, the crosslinked films released 139.4 ± 20.9 µg/cm2 of β-peptide. The release profile reported in this study is different from previously published profiles for the release of β-peptide from CH/HA films fabricated on the inner lumens of catheter tube segments, which eluted approximately 350 µg/mL of β-peptide over a period of 100–150 days [41,45]. We note that, for the purposes of this study achieving β-peptide release quantities that were selective to S. aureus vs MC3T3-E1 cells was a primary focus; the β-peptide concentration selected for loading these films was thus significantly lower than that used in our previous studies. In addition, chemical crosslinking of CH/HA films, differences in β-peptide sequence, the changes in underlying substrate properties and film-fabrication protocols (e.g., immersion versus flow-based methods) could also contribute to these differences in loading and release. We note further that the release profile reported here is appropriate in the context of orthopaedic devices, because the constant rate of β-peptide release was tuned to achieve β-peptide concentrations near the S. aureus biofilm MBPC (4 µg/mL, Figure 1) over extended periods of time. Also, the localized release of β-peptide reported here is promising in the context of achieving over-MBPC drug concentrations at specific high risk sites, such as orthopaedic device surfaces, which not only results in enhanced effectiveness against preventing S. aureus biofilms but also reduces the possibility of microbial cells developing β-peptide resistance [67]. Finally, by controlling the β-peptide release concentration we also reduce potential β-peptide toxicity against MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells, thereby mitigating adverse effects on osseointegration.

Finally, we also evaluated how the film thickness changed upon the chemical crosslinking of these films and upon β-peptide incorporation [41,44]. We used a focused ion beam-scanning electron microscope (FIB-SEM) to generate vertical cross-section images of uncrosslinked films, crosslinked films lacking β-peptide, and crosslinked films loaded with β-peptide. Crosslinked films incubated in β-peptide solution had a thickness of 705 ± 146 nm (Figure 4D, S1), significantly greater than crosslinked films lacking β-peptide (148 ± 90 nm; p < 0.001; Figure 4C, S1). The thickness of uncrosslinked films (224 ± 73 nm) was not significantly different from the thickness of crosslinked films (Figure S1). The increase in film thickness after loading with β-peptide is in accordance with those of previous studies on uncrosslinked CH/HA films fabricated using other methods [41,44].

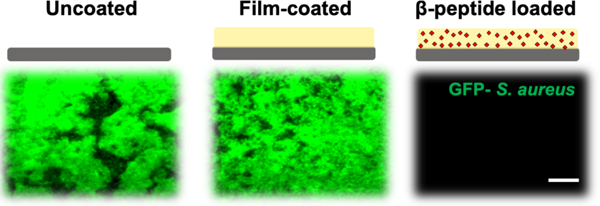

3.3. β peptide-containing coatings prevent S. aureus biofilms

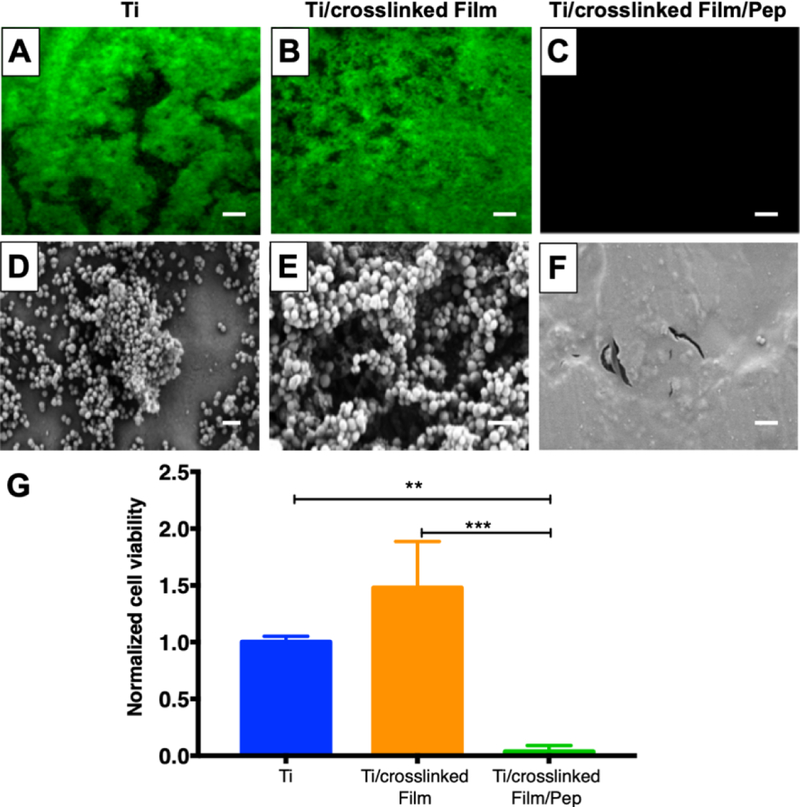

The antimicrobial activity of titanium substrates coated with β-peptide-containing films was characterized by incubating uncoated titanium, coatings without β-peptide, and coatings loaded with β-peptide with an inoculum of S. aureus (106 CFU/mL) in MH medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose at 37°C for 24 hr. Afterwards, the extent of the resulting biofilms formed was evaluated (i) qualitatively by inspecting biofilm density using the GFP-expressing S. aureus strain (AH1756) and SEM imaging for characterization of biofilm morphology, and (ii) quantitatively by measuring biofilm metabolic activity via an XTT assay. The fluorescence micrographs in Figure 5A–C reveal that robust biofilms formed on the surfaces of uncoated titanium and film-coated titanium substrates without β-peptide, but that β-peptide-loaded films completely prevented biofilm formation. SEM images reveal biofilms on uncoated substrates and substrates coated with control films without β-peptide to be composed of spherical bacterial 3D cell clusters encased by matrix (Figure 5D–E and Figure S5). In contrast, biofilm was not observed on β-peptide-loaded films by SEM imaging (Figure 5F and Figure S5), in accordance with the fluorescence micrographs. Quantification of S. aureus metabolic activity (Figure 5G) confirmed a virtual prevention of biofilm formation on β-peptide-loaded coatings compared to uncoated substrates and films lacking β-peptide. Finally, similar initial attachment densities of S. aureus cells on uncoated (243.2 ± 15.2 CFU/cm2) and film-coated surfaces (256.5 ± 41.6 CFU/cm2) were observed 2 hr after addition of the S. aureus inoculum, indicating that the initial attachment densities of S. aureus on these surfaces were similar. Overall, these results demonstrate that these β-peptide loaded coatings can prevent S. aureus biofilm formation on the surfaces of titanium substrates.

Figure 5:

Evaluation S. aureus biofilm formation on titanium substrates coated with β-peptide-loaded CH/HA films. Uncoated, crosslinked CH/HA film-coated, and crosslinked CH/HA film-coated and β-peptide loaded titanium substrates were incubated for 24 hr with S. aureus cells (106 CFU/mL) in biofilm inducing conditions (37°C, MH medium + 0.5% glucose). A–C) Representative fluorescence micrographs of GFP-expressing S. aureus strain AH1726 biofilms formed on the surfaces of A) uncoated, B) crosslinked film-coated (19.5 CH/HA bilayers) and C) crosslinked film-coated (19.5 CH/HA bilayers) β-peptide-loaded (0.44 mg/mL for 24 hr) titanium substrates. D-F) Representative SEM images showing the morphology of S. aureus biofilms formed on the surface of D) uncoated, E) crosslinked CH/HA film-coated and F) β-peptide-loaded crosslinked CH/HA film-coated titanium substrates. Scale bar: (A–C) 260 µm, (D–E) 2µm. G) Quantification of live S. aureus cells on uncoated, crosslinked CH/HA film-coated, and β-peptide-loaded crosslinked CH/HA film-coated titanium substrates. S. aureus cell viability was quantified using an XTT metabolic activity assay and normalized to the uncoated control. Data points represent the mean values and error bars are the standard deviation of three independent experiments. Asterisks (*) indicate p < 0.01 by two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Following this proof-of-concept demonstration that β-peptide-containing coatings can prevent S. aureus biofilm formation in the short-term, we also evaluated their ability to resist S. aureus biofilm formation at longer time points, after some of the β-peptide had eluted from the films. For these experiments, we incubated titanium substrates coated with β-peptide-loaded films in PBS for up to 60 days, replacing the PBS solution every 2 days. At desired time points, substrates were challenged with an S. aureus inoculum and viability of the resulting biofilms was assessed 24 hr later. Results shown in Figure 6 demonstrate that coatings loaded with β-peptide virtually prevented the formation of S. aureus biofilms for up to 24 days after initiation of β-peptide elution. This extended prevention of biofilm formation is consistent with the gradual release of β-peptides from the coatings over a period of just 28 days (Figure 4). After 36 days, we also observed significant decrease in biofilm viability, with about 60% less biofilm viability on coatings loaded with β-peptide compared to bare titanium (Figure 6B). These results are consistent with elution of sub-MBPC quantities of β-peptides from film-coated surfaces which resulted in measurable, but reduced compared to the control, S. aureus biofilm formation. Furthermore, as a general trend we also observed a small increase in S. aureus biofilm formation on crosslinked film-coated substrates compared to uncoated substrates. This increase in biofilm formation only achieved statistical significance (p<0.05) after 6 and 12 days of incubation in PBS. High variability in the extent of biofilms formed might result from small variations in cell attachment or proliferation that amplify during growth of the biofilm. These results suggest that the chemical or mechanical properties of CH/HA films lacking β-peptide may lead to greater biofilm formation than bare titanium [53,68]. Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that β-peptide-containing CH/HA films prevented S. aureus biofilm formation up to 24 days after fabrication.

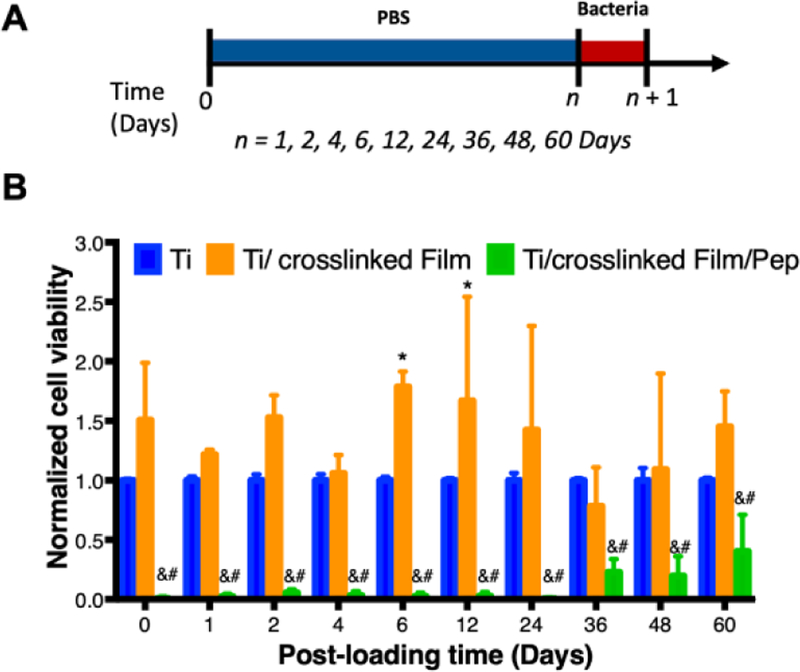

Figure 6:

Quantification of S. aureus biofilm prevention by β-peptide-loaded CH/HA films on titanium substrates after β-peptide elution in PBS for extended time. Uncoated, crosslinked film-coated (19.5 CH/HA bilayers), and crosslinked film-coated (19.5 CH/HA bilayers) and β-peptide loaded (0.44 mg/mL for 24 hr) titanium substrates were incubated for extended periods of time (0–60 days) in PBS followed by being challenged once with an inoculum of S. aureus cells (106 CFU/mL) in biofilm inducing conditions (37°C, MH medium + 0.5% glucose) for 24 hr. A) Schematic for the protocol used when performing long-term bacterial biofilm prevention experiments. B) Long-term antimicrobial activity of uncoated, crosslinked film-coated and crosslinked film-coated β-peptide-loaded titanium substrates after being pre-incubated in PBS (750 µL) and challenged with S. aureus. Data points represent the mean values and error bars are the standard deviation of three independent experiments. Asterisks (*) indicate p ≤ 0.05 between Ti and Ti/crosslinked film, # indicates p ≤ 0.05 between Ti and Ti/crosslinked film/Pep, and & indicates p < 0.01 between Ti/crosslinked film and Ti/crosslinked film/Pep by two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

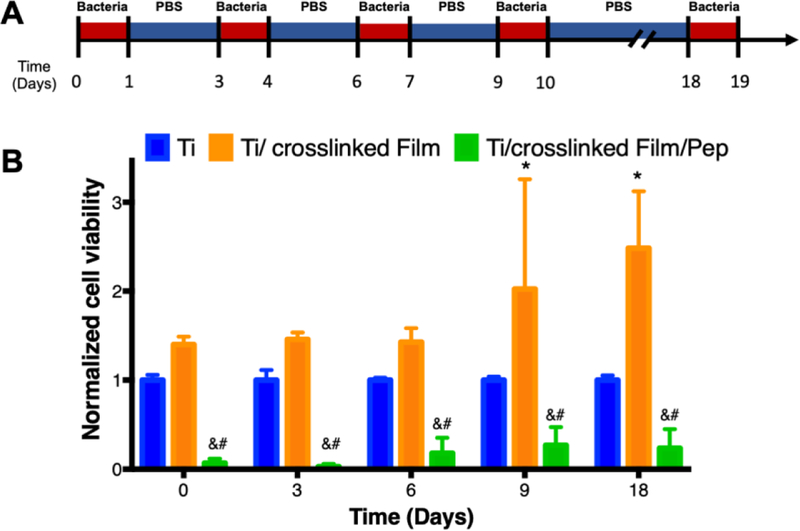

Finally, we evaluated the ability of the β-peptide-loaded films to resist multiple bacterial challenges, as might occur after implantation of an orthopaedic device in vivo. We presented the substrates with five inocula of S. aureus cells containing 106 CFU/mL for 24 hr each, washing the substrates between challenges (Figure 7A). As demonstrated in Figure 7, the β-peptide-loaded coatings prevented S. aureus biofilms after being challenged 5 times over a period of 18 days. However, the extent of reduction in biofilm viability was reduced for the last three challenges (~75% biofilm inhibition relative to uncoated control) compared to the first two challenges (~99% biofilm inhibition relative to uncoated control) (Figure 7B). Fluorescence micrographs of the biofilms formed on the surfaces of uncoated titanium substrates, coatings lacking β-peptide, and coatings loaded with β-peptide confirmed the quantitative results reported in Figure 7B (Figure S6). Fluorescence micrographs acquired during the first two challenges demonstrate complete prevention of S. aureus biofilms (Figure S6G and H) compared to uncoated substrates and control films lacking β-peptide (Figure S6A–B, D–E). However, following the fifth challenge we did not observe complete prevention of biofilms on β-peptide-loaded coatings. In this instance, we observed the formation of less robust biofilms on β-peptide-loaded films (Figure S6I) as compared to uncoated titanium and control films lacking β-peptide (Figure S6C and F). These results are consistent with depletion of β-peptide during multiple challenges to the point that the β-peptide MBPC is no longer achieved.

Figure 7:

Quantification of S. aureus biofilm prevention by β-peptide-loaded CH/HA films on titanium substrates after multiple short-term challenges. Uncoated, crosslinked film-coated, and crosslinked film-coated and β-peptide loaded titanium substrates were challenged with an 750 µL S. aureus inoculum (106 CFU/mL) for 24 hr, followed by incubation in PBS for the specified period of time. These challenges were repeated using a 106 CFU/mL S. aureus inocula until a total of 5 different challenges was performed. A) Schematic for the protocol used when performing multiple S. aureus challenge experiments. B) Antimicrobial activity of uncoated, film-coated, and β peptide post-loaded titanium substrates after multiple challenges with S. aureus inoculum. S. aureus cell viability was quantified using an XTT metabolic activity assay and normalized to the uncoated control. Data points represent the mean values and error bars are the standard deviation of three independent experiments. Asterisks (*) indicate p ≤ 0.05 between Ti and Ti/crosslinked film, # indicates p ≤ 0.05 between Ti and Ti/crosslinked film/Pep, and & indicates p < 0.01 between Ti/crosslinked film and Ti/crosslinked film/Pep by two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

In summary, the results presented here suggest that crosslinked CH/HA films loaded with an antimicrobial β-peptide may be a promising approach for inhibiting S. aureus colonization and biofilm formation on titanium orthopaedic devices after implantation (Figure 5), with the ability to resist multiple S. aureus challenges and prevent biofilm formation for several weeks. These results may improve on the short-term antimicrobial activity of current coatings focused on titanium surface modifications for preventing S. aureus cell attachment [53,69,70] and demonstrate the effectiveness in preventing biofilms after eluting relevant antibiotic quantities in short time-periods (e.g., hours to days only) [22,53,55,71]. Additionally, our results demonstrate inhibition of S. aureus biofilms in a time frame (e.g., 2 months after surgical implantation) at which patients are most susceptible to microbial colonization. Therefore, our proposed therapeutic approach could potentially improve healing and further prevent implant failure in healthcare settings [15].

3.4. β-peptide-containing coatings elute β-peptide concentrations biocompatible with MC3T3-E1 cells

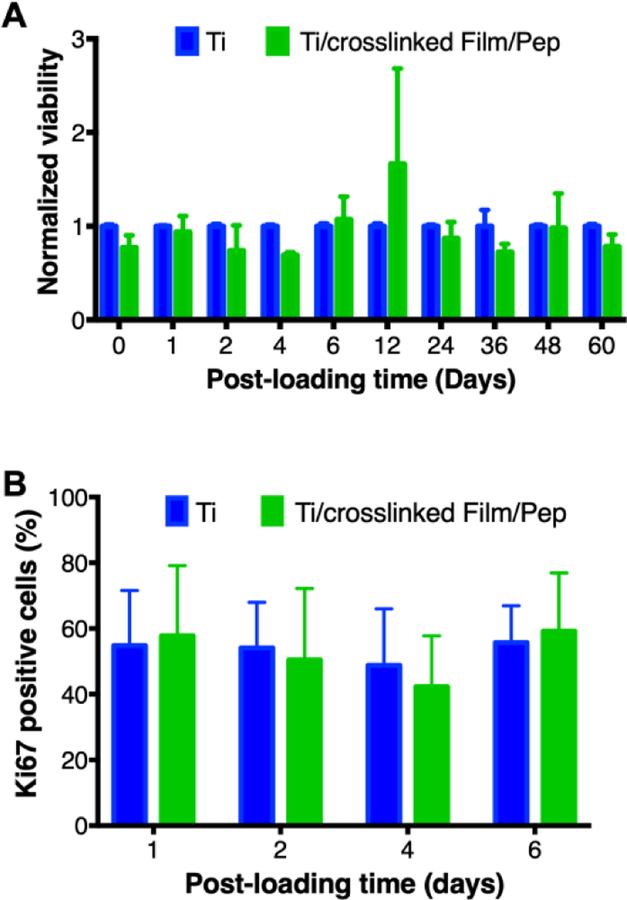

Many antimicrobial strategies have been reported for the prevention of implant-related bacterial infections. The adaptation of these strategies to orthopaedic implants should consider their biocompatibility with the bone microenvironment, including potential effects on bone cells [18,54,70]. Our results described above demonstrate that β-peptides in solution can prevent S. aureus biofilm formation with minimal toxicity against MC3T3-E1 cells. In addition, release of antimicrobial β-peptides from crosslinked films on titanium can prevent S. aureus biofilm formation. We next assessed the biocompatibility of our β-peptide-containing coatings incubated directly with MC3T3-E1 cells. The cytotoxicity of β-peptide-loaded films was evaluated by seeding MC3T3-E1 cells (5 ×104 cells/cm2) on the surface of uncoated titanium surfaces and PEM films loaded with β-peptide. MC3T3-E1 viability of the attached cells to the substrates surface was quantified via a Cell Titer Glo assay after 24 hr. Our results demonstrate that films loaded with β-peptide (Figure 8A, green bars) supported a similar extent of MC3T3-E1 cell viability after 24 hr compared to uncoated titanium (Figure 8A, blue bars), suggesting that they are non-toxic to preosteoblast cells and exhibit good biocompatibility. Taken together with the results demonstrating S. aureus biofilm inhibition under these same conditions (Figure 5), these results indicate that β-peptide-loaded films can be designed to elute β-peptide quantities that prevent S. aureus biofilms but do not cause substantial MC3T3-E1 cell toxicity.

Figure 8:

Evaluation of MC3T3-E1 cell viability and percent of proliferative cells on β-peptide-loaded CH/HA film-coated titanium substrates for extended periods of time. Uncoated, substrates and β-peptide-containing crosslinked CH/HA film-coated titanium substrates were incubated for 24 hr with MC3T3-E1 cells (5 × 104 cells/cm2). A) MC3T3-E1 cell viability on β-peptide-loaded CH/HA film-coated substrates was quantified using a Cell Titer Glo assay and normalized to uncoated control. B) The percent of MC3T3-E1 proliferative cells was quantified by counting ki67 positive cells relative to the total cells attached on the substrates from immunofluorescence images taken after 105 cells/cm2 were incubated on the substrates for 24 hr (see Materials and Methods). Data points represent the mean values and error bars are the standard deviation of three independent experiments. No significant differences were found between Ti and Ti/crosslinked film/Pep by two-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

We also quantified the viability of MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells on β-peptide-loaded coatings formed on titanium substrates after β-peptide elution in PBS for up to 60 days prior to MC3T3-E1 cell seeding. The viability of the MC3T3-E1 cells on films loaded with β-peptide was not significantly different than viability on bare titanium (Figure 8A). Visual inspection of MC3T3-E1 attachment after incubation in PBS for up to 6 days also demonstrated similar extent of cell attachment to β-peptide-loaded coatings and uncoated titanium substrates (Figure S7 A–D and I–L). Following confirmation that β-peptide containing films caused no changes in MC3T3-E1 cell viability, we also quantified MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation on film-coated and β-peptide-loaded titanium substrates after β-peptide elution in PBS for up to 6 days prior to MC3T3-E1 cell seeding. Visual inspection revealed no apparent differences in Ki67 expression in the cells attached to β-peptide-loaded and coated titanium substrates (Figure S7 M–P) compared to uncoated substrates (Figure S7 E–H). We quantified the percentage of Ki67-expressing MC3T3-E1 cells from immunofluorescence images. Results shown in Figure 8B indicate no significant differences in the percentage of proliferative MC3T3-E1 cells on β-peptide loaded film-coated titanium substrates relative to uncoated substrates. About 40–70% of the MC3T3-E1 cells expressed Ki67 (Figure 8B). When taken together, these long-term MC3T3-E1 viability (Figure 8A), proliferation results (Figure 8B), and the long-term biofilm inhibition prevention assay (Figure 6B), demonstrate the selectivity of films loaded with β-peptide for inhibiting S. aureus biofilms without inducing MC3T3-E1 cell toxicity for prolonged periods.

4. Conclusions

This study used a layer-by-layer based approach to fabricate crosslinked CH/HA PEM films on titanium substrates. These films supported MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cell attachment and proliferation for up to 6 days. We also demonstrated the incorporation of an antimicrobial β-peptide within the crosslinked CH/HA films to yield coatings that release β-peptide over a period of 28 days, which is relevant in the context of inhibiting bacterial attachment and biofilm formation over short to medium-term time periods. Furthermore, we showed that films loaded with β-peptide successfully prevented S. aureus biofilms formation in vitro without significantly decreasing MC3T3-E1 viability, suggesting promise for these films in the context of developing orthopaedic implant surfaces that resist biofilm formation. This result also suggests the potential of developing novel strategies to inhibit biofilms without interfering with the osseointegration of orthopaedic devices. Moreover, β-peptide-loaded coatings inhibited S. aureus biofilm formation for up to 24 days and resisted five separate bacterial challenges over 18 days.

From this proof-of-concept demonstration, we conclude that crosslinked CH/HA PEM films loaded with an antimicrobial β-peptide are a novel and promising approach for inhibiting bacterial biofilms on orthopaedic devices and potentially reducing the occurrence of implant-associated infections in patients receiving orthopaedic devices. These promising results motivate further work to evaluate the ability of these β-peptide-loaded films to inhibit S. aureus biofilm-related bone infections in vivo, where flow and immune system interactions are present, as well as the development of more complex coatings (e.g., dual-delivery of antimicrobials and bone growth factors) that could also improve osseointegration. The coatings and strategies reported here also have the potential to be useful for inhibiting microbial colonization on the surfaces of other medical devices to potentially reduce the incidence of device-related infection in other contexts.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE:

Titanium (Ti) and its alloys are used widely in orthopaedic devices due to their mechanical strength and long-term biocompatibility. However, these devices are susceptible to bacterial colonization and the subsequent formation of biofilms. Here we report a chitosan and hyaluronic acid polyelectrolyte multilayer-based approach for the localized delivery of helical, cationic, globally amphiphilic β-peptide mimetics of antimicrobial peptides to inhibit S. aureus colonization and biofilm formation. Our results reveal that controlled release of this β-peptide can selectively kill S. aureus cells without exhibiting toxicity toward MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells. Further development of this polymer-based coating could result in new strategies for preventing orthopaedic implant-related infections, improving outcomes of these titanium implants.

5. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants 1R01 AI092225 and R21 AI127442 to S.P.P. and D.M.L. A. de L.R.L. and B.J.O. were partially supported by an AOF research scholarship from the Graduate Engineering Research Scholars at UW-Madison. B.J.O. was also supported by the National Institutes of Health Chemistry Biology Interface Training Grant NIGMS T32 GM008505. B.D.G. was supported by the National Institutes of Health Biotechnology Training Program grant T32 GM008349 and the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1647503. The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of facilities and instrumentation supported by the National Science Foundation through the University of Wisconsin Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (DMR-1121288). We thank Richard Noll for SEM training and help with FIB-SEM imaging. Finally, we thank Prof. Alexander Horswill at University of Colorado for providing the GFP-expressing S. aureus strain (AH1756).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Part of the Drug Delivery for Musculoskeletal Applications Special Issue, edited by Robert S. Hastings and Professor Johnna S. Temenoff.

6. References

- [1].Goodman SB, Yao Z, Keeney M, Yang F, The future of biologic coatings for orthopaedic implants, Biomaterials 34 (2013) 3174–3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Geetha M, Singh AK, Asokamani R, Gogia AK, Ti based biomaterials, the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants – A review, Prog. Mater. Sci 54 (2009) 397–425. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Montanaro L, Speziale P, Campoccia G, Ravaioli S, Cangini I, Pietrocola G, Giannini S, Arciola CR, Scenery of Staphylococcus implant infections in orthopedics, Future Microbiol 6 (2011) 1329–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Moriarty TF, Schlegel U, Perren S, Richards RG, Infection in fracture fixation: Can we influence infection rates through implant design?, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med 21 (2010) 1031–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Damiati L, Eales MG, Nobbs AH, Su B, Tsimbouri PM, Salmeron-Sanchez M, Dalby MJ, Impact of surface topography and coating on osteogenesis and bacterial attachment on titanium implants, J. Tissue Eng 9 (2018) 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Romanò CL, Scarponi S, Gallazzi E, Romanò D, Drago L, Antibacterial coating of implants in orthopaedics and trauma: a classification proposal in an evolving panorama, J. Orthop. Surg. Res 10 (2015) 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ribeiro M, Monteiro FJ, Ferraz MP, Infection of orthopedic implants with emphasis on bacterial adhesion process and techniques used in studying bacterial-material interactions., Biomatter 2 (2012) 176–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zimmerli W, Clinical presentation and treatment of orthopaedic implant-associated infection, J. Intern. Med 276 (2014) 111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Harris LG, Richards RG, Staphylococci and implant surfaces : a review, Injury 37 (2006) 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE, Prosthetic-joint infections, N Engl J Med 351 (2004) 1645–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Moran E, Byren I, Atkins BL, The diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infections, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 65 (2010) iii45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Olson ME, Horswill AR, Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis: bad to the bone., Cell Host Microbe 13 (2013) 629–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lora-Tamayo J, Murillo O, Iribarren JA, Soriano A, Sánchez-Somolinos M, Baraia-Etxaburu JM, Rico A, Palomino J, Rodríguez-Pardo D, Horcajada JP, Benito N, Bahamonde A, Granados A, Del Toro MD, Cobo J, Riera M, Ramos A, Jover-Sáenz A, Ariza J, A large multicenter study of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections managed with implant retention, Clin. Infect. Dis 56 (2013) 182–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stoodley P, Ehrlich GD, Sedghizadeh PP, Hall-Stoodley L, Baratz ME, Altman DT, Sotereanos NG, Costerton JW, Demeo P, Orthopaedic biofilm infections., Curr. Orthop. Pract 22 (2011) 558–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Raphel J, Holodniy M, Goodman SB, Heilshorn SC, Multifunctional coatings to simultaneously promote osseointegration and prevent infection of orthopaedic implants., Biomaterials 84 (2016) 301–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim BN, Kim ES, Oh M-D, Oral antibiotic treatment of staphylococcal bone and joint infections in adults, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 69 (2014) 309–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Arduino JM, Kaye KS, Reed SD, Peter SA, Sexton DJ, Chen LF, Hardy NC, Tong SY, Smugar SS, Fowler VG, Anderson DJ, Staphylococcus aureus infections following knee and hip prosthesis insertion procedures, Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 4 (2015) 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gallo J, Holinka M, Moucha CS, Antibacterial surface treatment for orthopaedic implants, Int J Mol Sci 15 (2014) 13849–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Darouiche RO, Device-associated infections: a macroproblem that starts with microadherence., Clin. Infect. Dis 33 (2001) 1567–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].del Pozo JL, Patel R, The Challenge of Treating Biofilm-associated Bacterial Infections, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 82 (2007) 204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Odekerken J, Welting T, Arts J, Walenkamp G, Emans PJ, Modern Orthopaedic Implant Coatings — Their Pro’s, Con’s and Evaluation Methods, in: Intech, 2013: pp. 45–73. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Moskowitz JS, Blaisse MR, Samuel RE, Hsu H-P, Harris MB, Martin SD, Lee JC, Spector M, Hammond PT, The effectiveness of the controlled release of gentamicin from polyelectrolyte multilayers in the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infection in a rabbit bone model., Biomaterials 31 (2010) 6019–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Batoni G, Maisetta G, Brancatisano FL, Esin S, Campa M, Use of Antimicrobial Peptides Against Microbial Biofilms: Advantages and Limits, Curr. Med. Chem 18 (2011) 256–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Huang HW, Action of Antimicrobial Peptides : Two-State Model, Biochemistry 39 (2000) 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dathe M, Wieprecht T, Structural features of helical antimicrobial peptides: Their potential to modulate activity on model membranes and biological cells, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr 1462 (1999) 71–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Karlsson AJ, Pomerantz WC, Neilsen KJ, Gellman SH, Palecek SP, Effect of Sequence and Structural Properties on 14-helical β-peptide activity against Candida albicans Planktonic Cells and Biofilms, ACS Chem. Biol 5 (2010) 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Raguse TL, Porter EA, Weisblum B, Gellman SH, Structure-Activity studies of 14-helical antimicrobial β-peptides: Probing the relationship between conformational stability and antimicrobial potency, J. Am. Chem. Soc 124 (2002) 12774–12785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Huang HW, Charron NE, Understanding membrane-active antimicrobial peptides, Q. Rev. Biophys 50 (2017) e10 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jackson M, Mantsch HH, Spencer JH, Conformation of magainin-2 and related peptides in aqueous solution and membrane environments probed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy., Biochemistry 31 (1992) 7289–7293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hancock REW, Sahl H-G, Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies., Nat. Biotechnol 24 (2006) 1551–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Aziz MA, Cabral JD, Brooks HJL, Moratti SC, Hanton LR, Antimicrobial properties of a chitosan dextran-based hydrogel for surgical use, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 56 (2012) 280–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Brogden KA, Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria?, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 3 (2005) 238–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Porter EA, Weisblum B, Gellman SH, Mimicry of host-defense peptides by unnatural oligomers: Antimicrobial β-peptides, J. Am. Chem. Soc 124 (2002) 7324–7330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Porter EA, Wang X, Lee H-S, Weisblum B, Gellman SH, Non-haemolytic β-amino-acid oligomers, Nature 404 (2000) 565–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lee MR, Raman N, Gellman SH, Lynn DM, Palecek SP, Hydrophobicity and helicity regulate the antifungal activity of 14-helical β-peptides, ACS Chem. Biol 9 (2014) 1613–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Arvidsson PI, Ryder NS, Weiss HM, Gross G, Kretz O, Woessner R, Seebach D, Antibiotic and hemolytic activity of a β2/β3 peptide capable of folding into a 12/10-helical secondary structure, ChemBioChem 4 (2003) 1345–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Godballe T, Nilsson LL, Petersen PD, Jenssen H, Antimicrobial β-Peptides and α-Peptoids, Chem. Biol. Drug Des 77 (2011) 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Raman N, Lee M-R, Lynn D, Palecek S, Antifungal activity of 14-helical β-peptides against planktonic cells and biofilms of candida species, Pharmaceuticals 8 (2015) 483–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Karlsson AJ, Pomerantz WC, Weisblum B, Gellman SH, Palecek SP, Antifungal Activity from 14-Helical β-Peptides, J. Am. Chem. Soc 128 (2006) 12630–12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Peterson AM, Pilz-Allen C, Kolesnikova T, Möhwald H, Shchukin DG, Growth factor release from polyelectrolyte-coated titanium for implant applications, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6 (2014) 1866–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Raman N, Marchillo K, Lee M-RM, Rodríguez López A.D.L.A. de L., Andes DRDR, Palecek SPSP, Lynn DMDM, Intraluminal release of an antifungal β-peptide enhances the antifungal and anti-biofilm activites of multilayer-coated catheters in a rat model of venous catheter infection, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 2 (2015) 112–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wang B, Jin T, Xu Q, Liu H, Ye Z, Chen H, Direct loading and tunable release of antibiotics from polyelectrolyte multilayers to reduce bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation, Bioconjug. Chem 27 (2016) 1305–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Flessner RM, Yu Y, Lynn DM, Rapid release of plasmid DNA from polyelectrolyte multilayers: a weak poly(acid) approach., Chem. Commun 47 (2011) 550–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Raman N, Lee MR, Palecek SP, Lynn DM, Polymer multilayers loaded with antifungal β-peptides kill planktonic Candida albicans and reduce formation of fungal biofilms on the surfaces of flexible catheter tubes, J. Control. Release 191 (2014) 54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Raman N, Lee M-RM-R, Rodríguez López ADL, Palecek SP, Lynn DM, Antifungal activity of a β-peptide in synthetic urine media: Toward materials-based approaches to reducing catheter-associated urinary tract fungal infections, Acta Biomater 43 (2016) 243–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wikler MA, Cockerill FR, Craig WA, Dudley MN, Eliopoulos GM, Hecht DW, Hindler JF, Sheehan DJ, Tenover FC, Turnidge JD, Weinstein MP, Zimmer BL, Jane FM, Swenson JM, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 2007.

- [47].Buck ME, Zhang J, Lynn DM, Layer-by-layer assembly of reactive ultrathin films mediated by click-type reactions of poly(2-alkenyl azlactone)s, Adv. Mater 19 (2007) 3951–3955. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bao X, Lian X, Hacker TA, Schmuck EG, Quian T, Bhute V, Han T, Shi M, Drowley L, Plowright AT, Wang Q-D, Goumans M-J, Palecek SP, Long-term self-renewing human epicardial cells generated from pluripotent stem cells under defined xeno-free conditions, Nat. Biomed. Eng 1 1 (2016) 00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Porter EA, Bernard Weisblum A, Gellman Samuel H., Mimicry of Host-Defense Peptides by Unnatural Oligomers: Antimicrobial β-Peptides, 124 (2002) 7324–7330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cheng RP, Gellman SH, DeGrado WF, β-peptides: From structure to function, Chem. Rev 101 (2001) 3219–3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Liu D, DeGrado WF, De novo design, synthesis, and characterization of antimicrobial β-peptides., J. Am. Chem. Soc 123 (2001) 7553–7559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nath SD, Abueva C, Kim B, Lee BTL, Chitosan-hyaluronic acid polyelectrolyte complex scaffold crosslinked with genipin for immobilization and controlled release of BMP-2, Carbohydr. Polym 115 (2015) 160–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Fu J, Ji J, Yuan W, Shen J, Construction of anti-adhesive and antibacterial multilayer films via layer-by-layer assembly of heparin and chitosan., Biomaterials 26 (2005) 6684–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Chua PH, Neoh KG, Shi Z, Kang ET, Structural stability and bioapplicability assessment of hyaluronic acid-chitosan polyelectrolyte multilayers on titanium substrates, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 87 (2008) 1061–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chua P-H, Neoh K-G, Kang E-T, Wang W, Surface functionalization of titanium with hyaluronic acid/chitosan polyelectrolyte multilayers and RGD for promoting osteoblast functions and inhibiting bacterial adhesion, Biomaterials 29 (2008) 1412–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Boudou T, Crouzier T, Auzély-Velty R, Glinel K, Picart C, Internal composition versus the mechanical properties of polyelectrolyte multilayer films: the influence of chemical cross-linking., Langmuir 25 (2009) 13809–13819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Richert L, Lavalle P, Payan E, Shu XZ, Prestwich GD, Stoltz JF, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Picart C, Layer by Layer buildup of polysaccharide films: Physical chemistry and cellular adhesion aspects, Langmuir 20 (2004) 448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Detzel CJ, Larkin AL, Rajagopalan P, Polyelectrolyte multilayers in tissue engineering., Tissue Eng. Part B 17 (2011) 101–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mendelsohn JD, Yang SY, Hiller J, Hochbaum AI, Rubner MF, Rational design of cytophilic and cytophobic polyelectrolyte multilayer thin films, Biomacromolecules 4 (2003) 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schneider A, Vodouhe C, Ludovic R, Francius G, Le Guen E, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Frisch B, Picart C, Multifunctional polyelectrolyte multilayer films: Combining mechanical resistance, biodegradability and bioactivity, Biomacromolecules 8 (2007) 139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Richert L, Boulmedais F, Lavalle P, Mutterer J, Ferreux E, Decher G, Schaaf P, Voegel J-C, Picart C, Improvement of stability and cell adhesion properties of polyelectrolyte multilayer films by chemical cross-linking., Biomacromolecules 5 (2004) 284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Richert L, Engler AJ, Discher DE, Picart C, Elasticity of native and cross-linked polyelectrolyte multilayer films, Biomacromolecules 5 (2004) 1908–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Schneider A, Francius G, Obeid R, Schwinté P, Hemmerlé J, Frisch B, Schaaf P, Voegel JC, Senger B, Picart C, Polyelectrolyte multilayers with a tunable young’s modulus: Influence of film stiffness on cell adhesion, Langmuir 22 (2006) 1193–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Tomihata K, Ikada Y, Crosslinking of hyaluronic acid with water-soluble carbodiimide, J. Biomed. Mater. Res 37 (1997) 243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Park S-N, Park J-C, Kim HO, Song MJ, Suh H, Characterization of porous collagen/hyaluronic acid scaffold modified by 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide cross-linking, Biomaterials 23 (2002) 1205–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Karlsson AJ, Flessner RM, Gellman SH, Lynn DM, Palecek SP, Polyelectrolyte multilayers fabricated from antifungal β-peptides: Design of surfaces that exhibit antifungal activity against Candida albicans, Biomacromolecules 11 (2010) 2321–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Simchi A, Tamjid E, Pishbin F, Boccaccini AR, Recent progress in inorganic and composite coatings with bactericidal capability for orthopaedic applications, Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol. Med 7 (2011) 22–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Seon L, Lavalle P, Schaaf P, Boulmedais F, Polyelectrolyte Multilayers: A Versatile Tool for Preparing Antimicrobial Coatings, Langmuir 31 (2015) 12856–12872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Besinis A, Hadi SD, Le HR, Tredwin C, Handy RD, Antibacterial activity and biofilm inhibition by surface modified titanium alloy medical implants following application of silver, titanium dioxide and hydroxyapatite nanocoatings, Nanotoxicology 11 (2017) 327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Carvalho AL, Vale AC, Sousa MP, Barbosa AM, Torrado E, Mano JF, Alves NM, Antibacterial bioadhesive layer-by-layer coatings for orthopedic applications, J. Mater. Chem. B 4 (2016) 5385–5393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Min J, Choi KY, Dreaden EC, Padera RF, Braatz RD, Spector M, Hammond PT, Designer Dual Therapy Nanolayered Implant Coatings Eradicate Biofilms and Accelerate Bone Tissue Repair, ACS Nano 10 (2016) 4441–4450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.