I focus particularly on the issue of patient preference, because many of my elderly patients would be insulted if I recommended not getting a screening mammogram. After a woman reaches 75 years of age I address mammography screening only if the patient initiates the topic.1

How does the above strategy resonate with your practice style? In this article, we address a simple question: When should we stop screening our patients for disease? The simple answer might be when the estimated risk of 10-year mortality is greater than the sum of the expected benefit of screening for disease. This solution reminds us of a quotation attributed to H.L. Mencken: “There is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.”2

Many physicians want to do better than simply omitting any discussion about cancer screening in older adults who are beyond the upper age limit of screening recommendations. Healthy and active older patients might benefit from continued screening, while others have health problems that override the potential to benefit. Given the possible development of frailty and the certainty of death, delivering preventive health care to the elderly, therefore, requires careful thought.3,4 More than 10 years ago, Mangin and colleagues asked us to rethink the concept of preventive health care for the elderly: “We need a way to assess prevention and treatment of risk factors in the elderly that takes a wider perspective when balancing potential harms against putative benefits.”5 What then are the issues that we should consider in decision making about screening in older patients, and how should we discuss screening with older patients?

Case description

Rachel, a 75-year-old woman, is checking in for a routine visit. Sitting outside the office door is Rachel’s 78-year-old husband, whom you last saw a few months ago. Jacques is a sedentary man who has never smoked. He has a history of gout, hypertension, and is “slowing down,” but generally feels well. At his last visit, Jacques had a blood pressure check and you renewed his medication. You recall a brief exchange about the negative results of his fecal immunochemical test (FIT) done 2 years earlier. You did not request another test.

As you are wrapping up her visit, Rachel challenges your omission of another FIT test for Jacques. After all, her husband was screened for colorectal cancer in the past. Was it now because he was “too old”? That put you on the spot—is there a simple way to explain the cascade of interventions that follow positive screening test results? What about cancer overdiagnosis? Not to mention competing risks of mortality .…

Deciding if an older patient would benefit from screening

Table 1 highlights many of the issues and steps that should be considered in decision making about screening in older patients.1,4,6–10 Physicians will need to individualize their approaches to screening because of a range of life expectancies for older patients of a given age, the potential for harms from screening and uncertain benefits, and individual patient preferences and values.

Table 1.

Steps for consideration and discussion when deciding if your older patient would benefit from screening

| STEPS | ISSUES FOR CONSIDERATION |

|---|---|

Determining whether to discuss screening with older patients

|

Clinical practice guidelines often recommend against screening in older patients based on a specific age or life expectancy Clinical trials on screening used to develop practice guidelines do not typically include people aged > 75 y |

Determining if older patients might benefit from screening

|

Benefits from screening occur downstream while harms typically occur immediately after screening Patients with life expectancy > 5–10 y have the potential to benefit from some screening interventions |

Discussing screening

|

Appropriate framing of discussions is important in developing individualized screening decisions (Box 1)10 |

Identifying patients who would probably not benefit from screening

|

Decision aids that explain the benefits and risks of screening in a manner more easily understood by patients (using absolute risk and natural frequencies) can be used to support shared decision making |

Identifying patients who have the potential to benefit from screening

|

Overscreening

Overscreening refers to the use of a screening test at ages younger or older than recommended or at a greater frequency than recommended (shorter rescreening interval). Overscreening also occurs when asymptomatic persons are tested in the absence of high-quality evidence to support the idea that such interventions improve health.11 Overscreening in older patients is a problem, given that, past a certain age, patients could be more likely to experience harm from screening, while it usually takes many years for any mortality benefit from screening to accrue.12,13

To avoid overscreening in the elderly, one consideration rises to the top: life expectancy. Two other considerations—namely patient values and preferences and downstream thinking about the possible outcomes of screening—are equally important but apply to people of all ages.

Life expectancy

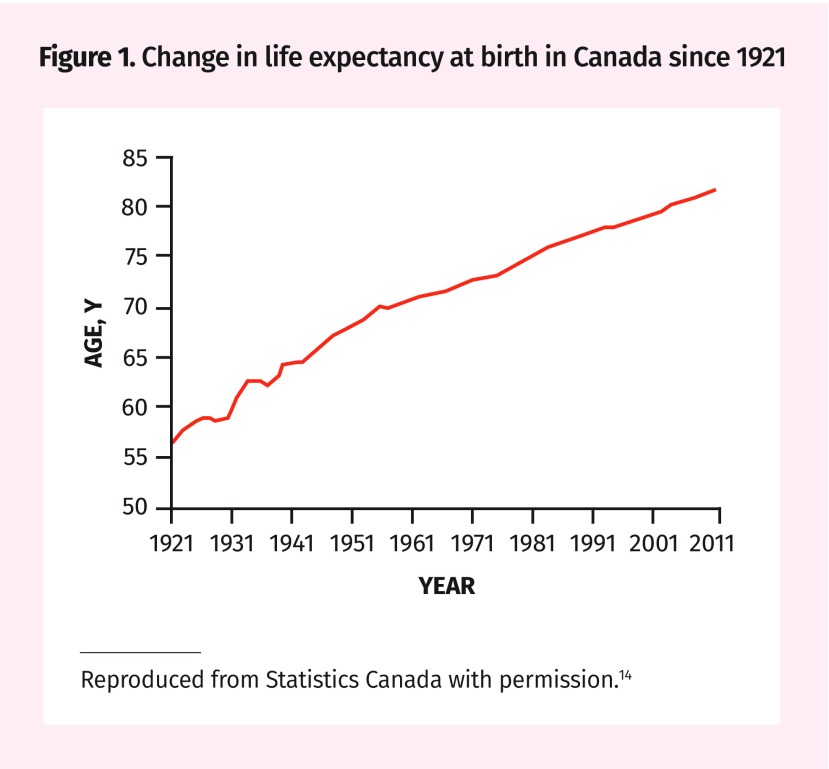

For decades, the life expectancy of Canadians has been slowly increasing (Figure 1).14 According to Statistics Canada,9 the average Canadian man at age 75 has 10 years of life expectancy; however, this typically includes some years of life in failing health. Table 2 provides estimates of median life expectancy at 75, 80, and 85 years, as well as a range of life expectancies influenced by the severity of comorbid conditions.7–9 Using this information can help to roughly estimate the life expectancy of your patient. The absolute risk of dying of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer, and estimates of mortality reduction from screening over the remaining lifetime of persons with a life expectancy like your patient, is also provided. You could use these estimates to give you an order of magnitude of a possible benefit from screening. For some ages no reduction in cancer mortality can be expected from screening. For example, women at age 80 in the lowest quartile of life expectancy should expect no reduction in mortality from screening for cancer. Models to estimate life expectancy have been developed in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom, and in testing some have been found to be fairly accurate.15,16 Such calculations can also be used to guide clinicians and might be of greater relevance to them than to their patients.

Figure 1.

Change in life expectancy at birth in Canada since 1921

Reproduced from Statistics Canada with permission.14

Table 2.

Estimates of life expectancy and mortality reduction from cancer screening at ages 75, 80, and 85 y: A) Breast, B) cervical, and C) colorectal cancer.

| A) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TASK FORCE RECOMMENDATIONS8 | AGE, Y | ESTIMATES TO FACILITATE SHARED DECISION MAKING* | |||

|

| |||||

| PERCENTILE | LIFE EXPECTANCY, Y | RESIDUAL LIFETIME RISK OF DYING OF BREAST CANCER, DEATHS PER 1000 | MORTALITY REDUCTION FOR BREAST CANCER BY SCREENING, DEATHS PER 1000 | ||

| Breast cancer (for 1000 women) | 75 | 25th | 6.8 | 9 | < 1 |

| 50th | 11.9 | 18 | 3 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 13.2 y | |||||

| No recommendation for women aged ≥ 75 y | 75th | 17 | 28 | 5 | |

|

| |||||

| 80 | 25th | 4.6 | 7 | NA† | |

| 50th | 8.6 | 15 | 2 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 10.1 y | |||||

| 75th | 13 | 24 | 4 | ||

|

| |||||

| 85 | 25th | 2.9 | 6 | NA† | |

| 50th | 5.9 | 12 | < 1 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 7.4 y | |||||

| 75th | 9.6 | 19 | 2 | ||

| B) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TASK FORCE RECOMMENDATIONS8 | AGE, Y | ESTIMATES TO FACILITATE SHARED DECISION MAKING* | |||

|

| |||||

| PERCENTILE | LIFE EXPECTANCY, Y | RESIDUAL LIFETIME RISK OF DYING OF CERVICAL CANCER, DEATHS PER 10 000 | MORTALITY REDUCTION FOR CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING, DEATHS PER 10 000 | ||

| Cervical cancer (for 10 000 women) | 75 | 25th | 6.8 | 7 | 1 |

| 50th | 11.9 | 12 | 4 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 13.2 y | |||||

| For women aged ≥ 70 y who have been adequately screened we recommend that routine screening cease (weak recommendation; low-quality evidence) | 75th | 17 | 19 | 8 | |

|

| |||||

| 80 | 25th | 4.6 | 5 | NA† | |

| 50th | 8.6 | 10 | 3 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 10.1 y | |||||

| 75th | 13 | 15 | 6 | ||

|

| |||||

| 85 | 25th | 2.9 | 4 | NA† | |

| 50th | 5.9 | 7 | < 1 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 7.4 y | |||||

| 75th | 9.6 | 12 | 3 | ||

| C) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TASK FORCE RECOMMENDATIONS8 | AGE, Y | ESTIMATES TO FACILITATE SHARED DECISION MAKING* | |||

|

| |||||

| PERCENTILE | LIFE EXPECTANCY, Y | RESIDUAL LIFETIME RISK OF DYING OF COLORECTAL CANCER, DEATHS PER 1000 | MORTALITY REDUCTION FOR COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING WITH GUAIAC FOBT, DEATHS PER 1000 | ||

| Colorectal cancer (for 1000 women or men) | 75 (women) | 25th | 6.8 | 9 | < 1 |

| 50th | 11.9 | 19 | 2 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 13.2 y | |||||

| We recommend not screening adults aged ≥ 75 y (weak recommendation; low-quality evidence) | 75th | 17 | 33 | 5 | |

|

| |||||

| 75 (men) | 25th | 4.9 | 8 | NA† | |

| 50th | 9.3 | 19 | 2 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 10.2 y | |||||

| 75th | 14.2 | 35 | 5 | ||

|

| |||||

| 80 (women) | 25th | 4.6 | 8 | NA† | |

| 50th | 8.6 | 18 | 2 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 10.1 y | |||||

| 75th | 13 | 30 | 4 | ||

|

| |||||

| 80 (men) | 25th | 3.3 | 8 | NA† | |

| 50th | 6.7 | 18 | 1 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 7.7 y | |||||

| 75th | 10.8 | 32 | 3 | ||

|

| |||||

| 85 (women) | 25th | 2.9 | 8 | NA† | |

| 50th | 5.9 | 16 | < 1 | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 7.4 y | |||||

| 75th | 9.6 | 25 | 2 | ||

|

| |||||

| 85 (men) | 25th | 2.2 | 8 | NA† | |

| 50th | 4.7 | 16 | NA† | ||

| Median life expectancy in Canada 5.4 y | |||||

| 75th | 7.9 | 27 | 2 | ||

Downstream thinking about the possible outcomes of screening

As Muir Gray has pointed out, “The harm from a screening programme starts immediately; the good takes longer to appear.”17 If the screening test results were positive, would your patient be willing to go down the path of diagnostic confirmation leading to treatment? In screening for colorectal cancer, a positive FIT result will raise the need for colonoscopy with biopsy, and a positive biopsy result will raise the issue of fitness to thrive following hemicolectomy. Regardless of comorbidities, any person so diagnosed is now a “cancer patient” with all this can imply. While the concept of watchful waiting (or active surveillance) is gaining traction for some types of cancer (eg, prostate), it is not possible to know whether a specific patient was overdiagnosed with a slow-growing tumour that was never destined to cause harm to him or her. Cancer overdiagnosis is understandably a cause of much uncertainty.18

In our case, it seems reasonable to ask Jacques what he would like his doctor to do. Would he have a colonoscopy in the event of a positive FIT result? In an asymptomatic patient, the purpose of screening is to treat any disease uncovered. If further testing, biopsy, or treatment would be declined, then no screening should be done in the first place (primum non nocere).

Shared decision making and patient values and preferences

When should one stop cancer screening? To the best of our knowledge, there is no systematic review examining the values and preferences of older patients around this question. That said, the concern expressed by Rachel and Jacques is not trivial given the rising incidence of cancer in older people. The big question is whether screening Jacques would add life to his years or years to his life.3 Treatment could certainly lower his quality of life; and many patients underestimate the harms of medical intervention,19 which might be greater with advancing age. Although Jacques could live to age 88, he could be told the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care made a recommendation against screening for colon cancer after age 7520; however, this is based on low-quality evidence and is a conditional (or weak) recommendation, which implies a need to consider individual patient situations including values and preferences.

One way to approach this case is through shared decision making with the patient or family members. Shared decision making is a structured process to incorporate values and preferences into screening and treatment decisions.21 Shared decision making is especially important for implementation of conditional or weak recommendations.22 When bringing up the idea that cancer screening might no longer be beneficial given a patient’s life expectancy, using direct language, such as “You might not live long enough to benefit from this test,” can be perceived as overly harsh. Instead, a statement such as the following might be better received: “This test is unlikely to help you live longer. Your other health issues should take priority.” Jacques should be informed that, in screening with a fecal occult blood test, the lag time to benefit has been estimated to be 10.3 years for an absolute reduction of 1 death prevented for 1000 persons screened.12

In screening for colorectal cancer after age 75, guidelines from the United Kingdom and the United States recommend that the decision to screen be an individual one.13 For some cancers, there is international agreement among guideline committees on the age to stop (eg, age 75 for breast cancer).23 This guidance, as with the age to stop screening for colon cancer, is based on the absence of direct trial evidence to quantify the benefits and harms for women who outlive the recommended age for screening. In the absence of trial evidence, it is not easy to quantify the net benefit of preventive activities.

For patients who express a willingness to continue screening into advanced age, a values clarification exercise should be considered, once patients are informed of the uncertainty of benefit and possible harms. By values clarification we mean having a conversation about what matters most to our patients and their families in terms of health outcomes. This conversation can be helped by making time to work through a decision aid, such as the one on screening for breast cancer for women aged 75 to 84.24 Research suggests the greatest potential for improvement in practice is in having such a conversation.25

Framing the discussion on screening in older patients

Older adults might not consider life expectancy important in screening and might not welcome a discussion of their life expectancy when discussing screening.6 In our discussions with older adults, we should use phrases that are generally preferred by patients to explain cessation of routine cancer screening. Box 1 provides the phrases that were most and least preferred by older American adults.10

Box 1. Phrases to explain stopping cancer screening.

Most preferred by patients

Your other health issues should take priority

This test is not recommended for you by medical guidelines

You are unlikely to benefit from this test

We usually stop doing this test at your age

You are at high risk of harm from this test

We should focus on quality of life instead of looking for cancer

Least preferred by patients

The doctor does not give an explanation

The doctor does not mention this test

You might not live long enough to benefit from this test

This test can be very inconvenient to complete

This test can be very uncomfortable

Adapted from Schoenborn et al.10

Physicians can provide their patients with decision aids as tools to supplement the discussion in the office.26 Implementing patient decision aids during the clinical encounter can be challenging, as many people have difficulty understanding the concept of risk.27–29 As we discussed in a recent article on organizing a practice for screening, there are compelling reasons to involve different members of the primary care team in screening activities.30 For example, we could further develop the role of nursing.

And in the end …

Rachel and Jacques wonder about his continuing to be screened for colorectal cancer. Using Table 2,7–9 you estimate Jacques to be at the 50th percentile for men about 80 years of age, giving him a good chance for more than 5 years of remaining life. You decide to invite Jacques for further discussion about the harms and benefits of continuing to be screened with the FIT. Further screening with the fecal occult blood test can minimally reduce the risk of death from colorectal cancer from about 18 to 17 per 1000 men at his age. He now understands the magnitude of a possible benefit from screening to be very small, with a 10-year lag time to benefit exceeding his estimated life expectancy. On the other hand, it is difficult to estimate the frequency of harms he might experience from screening. These harms include risks of dehydration from bowel preparation for colonoscopy, conscious sedation, bleeding or perforation from polyp removal, and the anesthesia of surgery. Based on this discussion, Jacques and Rachel decide to decline further screening.

There comes a time when many patients will have the good fortune to exceed the recommended age range for screening. For these people, we should consider an individualized shared decision making approach around the harms and benefits of screening.

Key points

▸ Older adults are at particular risk of harm from overscreening. This problem includes the use of screening tests at an age older than recommended or at a greater frequency (shorter interval) than recommended. Overscreening also occurs when asymptomatic persons are tested in the absence of high-quality evidence to support screening with a specific test.

▸ Any benefits from screening occur far into the future, while harms typically occur shortly after screening. Estimates of potential benefits and harms should be provided to older adults either as absolute risks or natural frequencies. Patient decision aids should be used to facilitate discussion of harms and benefits.

▸ Physicians should be prepared for shared decision making with older adults about screening. These discussions need to consider individual patient life expectancy, as well as values and preferences. An estimate of individual patient life expectancy beyond 10 years is usually required for benefit from screening.

▸ In framing discussions about stopping screening, physicians should consider patient communication preferences. Phrases indicating “your other health issues should take priority” or “the test is not recommended for you by medical guidelines” are most preferred, while phrases indicating “you will not live long enough to benefit from the screening test” or no discussion with the physician are least preferred.

Footnotes

Competing interests

All authors have completed the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ Unified Competing Interest form (available on request from the corresponding author). Dr Singh reports grants from Merck Canada, personal fees from Pendopharm, and personal fees from Ferring Canada, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro d’août 2019 à la page e329.

References

- 1.Parnes BL, Smith PC, Conry CM, Domke H. Clinical inquiries. When should we stop mammography screening for breast cancer in elderly women? J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):110–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wikiquote [website]. H. L. Mencken. Los Angeles, CA: Wikimedia Foundation Ltd; 2019. Available from: https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/H._L._Mencken. Accessed 2019 May 22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarfield AM. Screening in frail older people: an ounce of prevention or a pound of trouble? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):2016–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03070.x. Epub 2010 Oct 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbasi M, Rolfson D, Khera AS, Dabravolskaj J, Dent E, Xia L. Identification and management of frailty in the primary care setting. CMAJ. 2018;190(38):e1134–40. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.171509. Erratum in: CMAJ 2019;191(2):E54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangin D, Sweeney K, Heath I. Preventive health care in elderly people needs rethinking. BMJ. 2007;335(7614):285–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39241.630741.BE1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, Armacost K, Dy SM, Bridges JFP, et al. Older adults’ views and communication preferences about cancer screening cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1121–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care [website]. Published guidelines. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 2019. Available from: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/guidelines/published-guidelines. Accessed 2019 May 22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistics Canada. Life expectancy at various ages, by population group and sex, Canada. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2019. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310013401. Accessed 2019 May 22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoenborn NL, Janssen EM, Boyd CM, Bridges JFP, Wolff AC, Pollack CE. Preferred clinician communication about stopping cancer screening among older US adults: results from a national survey. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(8):1126–28. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebell M, Herzstein J. Improving quality by doing less: overscreening. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(1):22–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SJ, Leipzig RM, Walter LC. “When will it help?” Incorporating lag time to benefit into prevention decisions for older adults. JAMA. 2013;310(24):2609–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Preventive Services Task Force. Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, Bibbins-Domingo K, Caughey AB, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2564–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5989. Errata in: JAMA 2016;316(5):545, JAMA 2017;317(21):2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decady Y, Greenberg L. Health at a glance. Ninety years of change in life expectancy. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2014. Catalogue no. 82-624-X. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-624-x/2014001/article/14009-eng.htm. Accessed 2019 May 22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz M, Covinsky K, Widera EW, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Lee SJ. Predicting 10-year mortality for older adults. JAMA. 2013;309(9):874–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi LC, Jackson SE, Lee SJ, Wardle J, Steptoe A. The development and validation of an index to predict 10-year mortality risk in a longitudinal cohort of older English adults. Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):427–32. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muir Gray JA. Evidence-based healthcare and public health: how to make decisions about health services and public health. 3rd ed. Edinburgh, Scot: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahal BA, Butler S, Franco I, Spratt DE, Rebbeck TR, D’Amico AV, et al. Use of active surveillance or watchful waiting for low-risk prostate cancer and management trends across risk groups in the United States, 2010–2015. JAMA. 2019;321(7):704–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C. Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):274–86. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for colorectal cancer in primary care. CMAJ. 2016;188(5):340–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151125. Epub 2016 Feb 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grad R, Légaré F, Bell NR, Dickinson JA, Singh H, Moore AE, et al. Shared decision making in preventive health care. What it is; what it is not. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:682–4. (Eng), e377–80 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thombs BD, Straus SE, Moore AE, Canadian Task Force for Preventive Health Care. Update on task force terminology and outreach activities. Advancing guideline usability for the Canadian primary care context. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65:12–3. (Eng), e5–7 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebell MH, Thai TN, Royalty KJ. Cancer screening recommendations: an international comparison of high income countries. Public Health Rev. 2018;39:7. doi: 10.1186/s40985-018-0080-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute [website]. Patient decision aids. Decision aid summary. Ottawa, ON: The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2017. Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZsumm.php?ID=1908. Accessed 2019 May 22. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diendéré G, Dansokho SC, Rocque R, Julien AS, Légaré F, Côté L, et al. How often do both core competencies of shared decision making occur in family medicine teaching clinics? Can Fam Physician. 2019;65:e64–75. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/cfp/65/2/e64.full.pdf. Accessed 2019 Jun 12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore AE, Straus SE, Kasperavicius D, Bell NR, Dickinson JA, Grad R, et al. Knowledge translation tools in preventive health care. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:853–8. (Eng), e466–72 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scalia P, Durand MA, Berkowitz JL, Ramesh NP, Faber MJ, Kremer JAM, et al. The impact and utility of encounter patient decision aids: systematic review, meta-analysis and narrative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):817–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.020. Epub 2018 Dec 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang E, Bell NR, Dickinson JA, Grad R, Kasperavicius D, Moore AE, et al. Eliciting patient values and preferences to inform shared decision making in preventive screening. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:28–31. (Eng), e13–6 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell NR, Dickinson JA, Grad R, Singh H, Kasperavicius D, Thombs BD. Understanding and communicating risk. Measures of outcome and the magnitude of benefits and harms. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:181–5. (Eng), 186–91 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson BJ, Bell NR, Grad R, Thériault G, Dickinson JA, Singh H, et al. Practice organization for preventive screening. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:816–20. (Eng), e477–82 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]