Abstract

Accumulation of damaged mitochondria is a hallmark of aging and age-related neurodegeneration, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The molecular mechanisms of impaired mitochondrial homeostasis in AD are being investigated. Here we provide evidence that mitophagy is impaired in the hippocampus of AD patients, in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived human AD neurons, and in animal AD models. In both amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau Caenorhabditis elegans models of AD, mitophagy stimulation (through NAD+ supplementation, urolithin A, and actinonin) reverses memory impairment through PINK-1 (PTEN-induced kinase-1)-, PDR-1 (Parkinson’s disease-related-1; parkin)-, or DCT-1 (DAF-16/FOXO-controlled germline-tumor affecting-1)-dependent pathways. Mitophagy diminishes insoluble Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 and prevents cognitive impairment in an APP/PS1 mouse model through microglial phagocytosis of extracellular Aβ plaques and suppression of neuroinflammation. Mitophagy enhancement abolishes AD-related tau hyperphosphorylation in human neuronal cells and reverses memory impairment in transgenic tau nematodes and mice. Our findings suggest that impaired removal of defective mitochondria is a pivotal event in AD pathogenesis and that mitophagy represents a potential therapeutic intervention.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Mitochondria produce the necessary ATP for the survival and optimal function of neurons, and mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with aging and neurodegenerative diseases1,2. In AD, neurons experience mitochondrial dysfunction and a bioenergetic deficit that may contribute to the disease-defining Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) pathologies; conversely, Aβ and tau pathologies can promote mitochondrial defects2,3. Impairment of mitochondrial function is a fundamental phenomenon in AD since it exists in human samples of both sporadic and familial types of the disease, as well as in the brain tissues of transgenic AD mouse models2,4. At the cellular level, non-glycosylated, full-length amyloid precursor protein (APP) and C terminus truncated APP anchor in the mitochondrial protein import channels (mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM40 homolog and mitochondrial import inner membrane translocase subunit Tim23), blocking the entry of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins5. Mitochondrial dysfunction-induced energy deficiency and Aβ1–42 oligomers trigger intracellular Ca2+ imbalance and 5’ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation, leading to synaptotoxicity and memory loss2,6. Furthermore, while axonal transport of mitochondria is critical for neuronal function, Aβ1–42 and p-tau induce defects in axonal transport, resulting in synapse starvation, ATP depletion, and ultimately neurodegeneration7–9. Thus, there is a sophisticated set of connections between mitochondrial impairment and these two AD pathological factors, suggesting that targeting defective mitochondria may be an important approach for AD therapy.

Mitochondrial quality control is regulated by the processes of mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy. Mitophagy involves the targeting of damaged or superfluous mitochondria to the lysosomes wherein the mitochondrial constituents are degraded and recycled10,11. In mammals, over 20 proteins have been reported as necessary for mitophagy, including PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), parkin, serine/threonine-protein kinase ULK1 (ULK1), BCL2/ adenovirus E1B 19 kDa protein-interacting protein 3-like (BNIP3L/ NIX), and serine/threonine-protein kinase TBK1 (TBK1)2. Commensurate with an age-dependent increase in the incidence of AD, there is also an age-dependent accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and impaired mitophagy2. Importantly, mitophagy plays a critical role in neuronal function and neuronal survival through the maintenance of a healthy mitochondrial pool and the inhibition of neuronal death11,12. However, the role of mitophagy in AD progression is unclear. Utilizing postmortem human AD brain samples, AD induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurons, and transgenic animal models of AD, we show defective mitophagy in AD. Furthermore, the restoration of mitophagy ameliorates memory loss in both Caenorhabditis elegans and two mouse models of AD through the inhibition of Aβ plaques and p-tau. Here we propose that defective mitophagy induces the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, thereby promoting AD pathology and memory loss, and suggest that it is a target for drug therapy.

Results

Defective mitophagy in the hippocampal samples of AD patients and in AD iPSC-derived neurons.

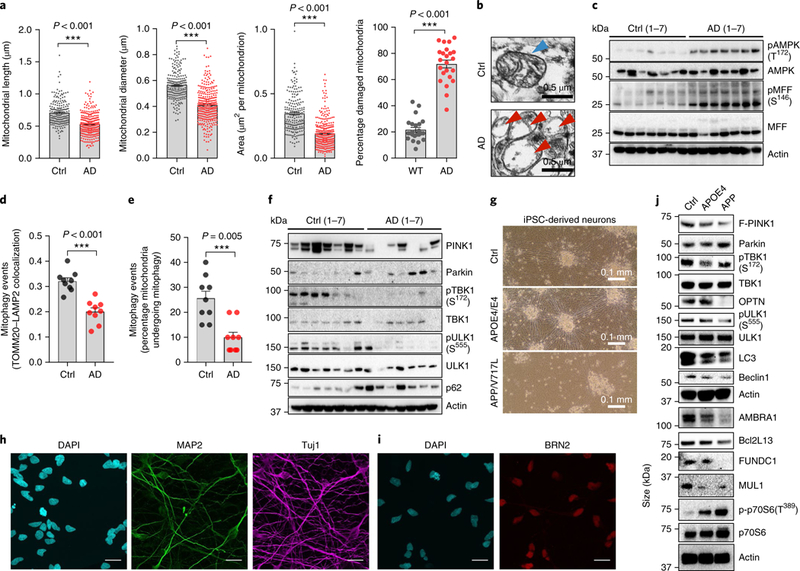

To uncover the cellular and molecular causes of mitochondrial impairment and the accumulation of damaged mitochondria in AD, we examined neuronal mitochondrial morphology in postmortem hippocampal tissues from age- and sex-matched AD patients and healthy individuals (patient information in Supplementary Table 1). Hippocampal neurons in the AD samples displayed altered mitochondrial morphology characterized by reduced size and excessive mitochondrial damage compared to healthy controls (Fig. 1a,b). Dysfunctional mitochondria are deficient at energy production, resulting in ATP depletion and stimulation of AMPK, an evolutionarily conserved master regulator of energy expenditure and mitochondrial homeostasis13–15. In wild-type (WT) cells, activated AMPK coordinates mitochondrial fragmentation through the stimulation of mitochondrial fission factor (MFF), and mitophagic clearance of defective organelles in response to bioenergetic stress14,15. In human AD hippocampal tissue, we detected a large increase in the activity of AMPK and its downstream effector MFF (Fig. 1c and quantification in Supplementary Fig. 1a). Interestingly, basal levels of mitophagy in the AD hippocampus were 30–50% lower than normal as monitored by the colocalization of the mitochondrial protein mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM20 homolog (TOMM20) with lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 2 (LAMP2) lysosomal protein and quantification of mitophagy-like events using electron microscopy (Fig. 1d,e and Supplementary Fig. 1c). These findings show accumulation of damaged mitochondria in the hippocampus of AD patients due to defective mitophagy.

Fig. 1 |. Mitochondrial dysfunction and defective mitophagy in human patient brain samples and AD patient iPSC-derived cultured neurons.

a, Quantification of mitochondrial parameters from electron microscopy images in postmortem human hippocampal tissue from AD patients and age-matched healthy controls; n = 300 mitochondria from 7 AD patients or 203 mitochondria from 7 healthy controls (ctrl). The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (***P< 0.001; two-sided Student’s t test). b, Representative set of electron microscopy images. c, Relative levels of proteins implicated in the AMPK pathway in postmortem human hippocampal tissue from AD patients and age-matched healthy controls. d, Quantification of the colocalization of the mitochondrial protein T0MM20 and the lysosomal protein LAMP2 using IHC. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 9 random fields from 3 AD patients or 3 healthy controls; ***P< 0.001; two-sided Student’s t test). e, Quantification of mitophagy-like events using electron microscopy images in postmortem human hippocampal tissue between AD patients and age-matched healthy controls. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 9 random fields from 3 AD patients or 3 healthy controls; ***P< 0.001; two-sided Student’s t test). f, Changes of designated mitophagy proteins in postmortem human hippocampal tissue from AD patients and age-matched healthy controls (n = 7 individuals for both the AD group and the healthy control group). g, Representative images of iPSC-derived neurons from an APP-mutation patient, an AP0E4 patient and healthy age-matched control cell line (28-day differentiation). h, Immunofluorescence microscopy for DAPI (nuclear staining), MAP2 (dendrite staining), and Tuj1 (staining of neuron-specific class III β-tubulin) in the control line neurons; scale bars, 50 μm. i, Immunofluorescence microscopy for DAPI (nuclear staining) and BRN2 (cortical upper layer marker) in the control line neurons; scale bars, 50 μm. j, Levels of mitophagy-related proteins in iPSC-derived neurons in three iPSC cell lines. c,f–j, A t least three experiments were repeated independently with similar results. Full scans of all the blots are in the Supplementary Note.

Mitophagy impairment in AD may occur despite AMPK activation and the abundance of smaller mitochondria, expected to be more readily removed by autophagic engulfment11,14,15. To address this apparent paradox, we systematically examined the protein levels of major factors involved in mitochondrial metabolism and mitophagy2. Mitophagy proteins PINK1, Bcl-2-like protein 13 (Bcl2L13), and BNlP3L/NlX were decreased in some AD individuals, and the mitophagy initiation proteins p-TBK1 (Ser172)16 and p-ULK1 (Ser555)15 were inactivated in all human AD samples (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1b). To investigate whether mitophagy is impaired in AD neurons, we established iPSC-derived neuronal cultures17 using a familial-AD mutant (APP/V717L), a sporadic AD (alipoprotein E4 (APOE4)/E4), and an age- and sex-matched healthy control (SBAD03–01) cell line (Fig. 1g–i). Using a well-established protocol17,18, we generated cortical neurons as evidenced by the expression of the dendritic marker microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), neuron-specific class III β-tubulin maker (Tuj1), and the cortical upper layer marker brain-specific homeobox/POU domain protein 2 (BRN2; Fig. 1h,i, healthy control neurons). We further confirmed the maturation of neuronal identity in the APOE4- and APP-derived neurons as evidenced by the expression of synaptophysin (a marker for presynaptic terminals; Supplementary Fig. 1d) and postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95, a marker of postsynaptic density in glutamatergic neurons; Supplementary Fig. 1e). Furthermore, we found that AD iPSC-derived neurons recapitulate the cellular features seen in human AD brain tissues, including increased DNA damage (higher γ-H2A histone family, member X signal), compromised mitochondrial homeostasis (lower sirtuin-1, PGC-1α, and superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial (SOD2)), increased mitochondrial fragmentation (higher p-dynamin-1-like protein (DRP1) Ser616 and p-MFF Ser146), and low ATP levels (Supplementary Fig. 1e–h). Importantly, phosphorylation of the mitophagic proteins TBK1 and ULK1 was reduced by more than 50% in AD compared to control neurons (Fig. 1j and quantification in Supplementary Fig. 1g). Reduction of p-TBK1 (Ser172) was also conserved in PSEN1 cell line-derived cortical neurons (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Additionally, levels of other major mitophagy proteins, such as activating molecule in BECN1-regulated autophagy protein 1 (AMBRA1), Bcl2L13, FUN14 domain-containing protein 1 (FUNDC1), and mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase activator of NFKB-1 (MUL1)2 were decreased in AD iPSC-derived neuronal cells (Fig. 1j). Notably, basal levels of autophagy were diminished in AD neurons (lower levels of lipid-modified microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3B-II) and beclin-1 in Fig. 1j and quantification in Supplementary Fig. 1g), which is in accord with previous reports19. Furthermore, we quantified autophagic flux using a monomeric red fluorescent protein-green fluorescent protein (GFP) tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3 plasmid (ptfLC3)11,20, with the data showing reduced numbers of both autophagosomes and autolysosomes in APP neurons compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 1i). These results suggest a normal autophagic flux, but the overall induction of the autophagy pathway was reduced. Thus, we detected impairment of mitophagy both in the hippocampal samples of AD patients and in AD iPSC-derived neurons.

Restoration of neuronal mitophagy ameliorates cognitive decline in C. elegans models of AD.

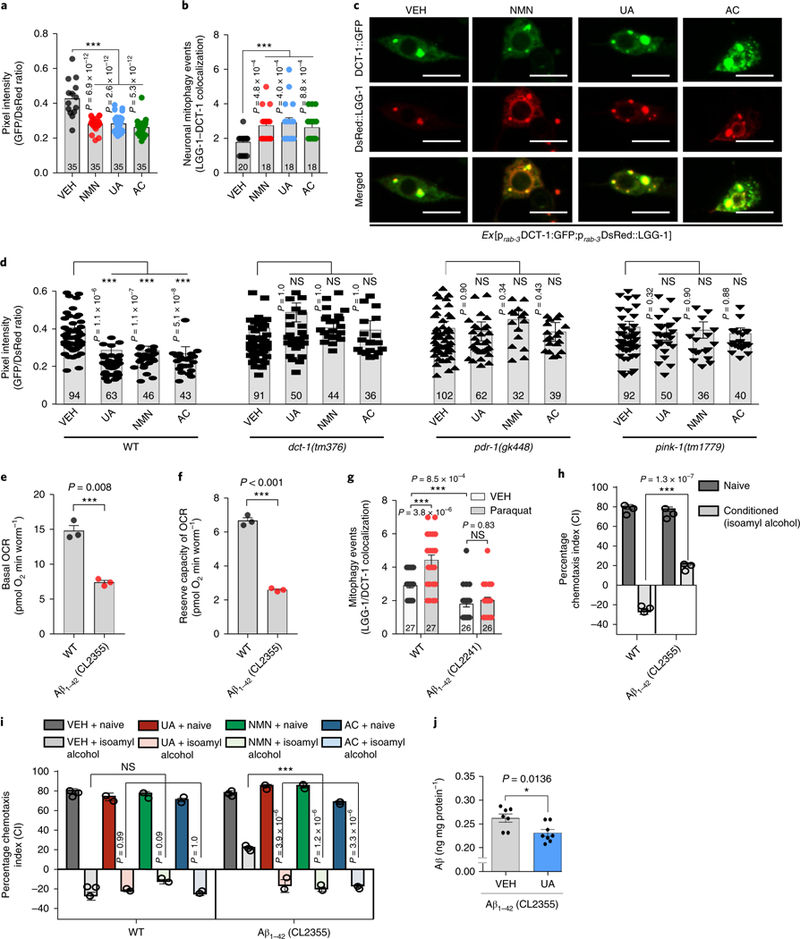

Mitophagy defects lead to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria, energy deprivation, inflammation, and eventually neuronal loss2,11,12,21. Hence, compromised mitophagy could contribute substantially to AD pathology. We next examined whether activation of neuronal mitophagy through pharmacological and genetic interventions would affect AD pathogenesis. We established an in vivo drug screening platform using C. elegans to identify potent neuronal mitophagy inducers, using a z-score standard as defined elsewhere22. Two different methods were used to detect neuronal mitophagy in vivo10,23. First, we generated transgenic animals expressing a pan-neuronal mitochondria-targeted Rosella (mtRosella) biosensor with a GFP variant sensitive to the acidic environment of the lysosomal lumen fused to the pH-insensitive Discosoma red fluorescent protein (DsRed). We tested nematodes carrying neuronal mtRosella under normal and mitophagy-inducing conditions to validate this approach. Under normal conditions, both GFP and DsRed events were present in the neurons of WT nematodes (Supplementary Fig. 2). Supplementation with an NAD+ precursor, such as nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), is known to induce mitophagy12,21,24,25. Indeed, NMN supplementation resulted in decreased GFP/DsRed ratio of mtRosella fluorescence, indicating mitophagy stimulation (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2). We then generated transgenic nematodes expressing the DAF-16/FOXO-controlled germline-tumor affecting-1 (DCT-1) mitophagy receptor fused with GFP together with the autophagosomal marker protein LGG-1 fused with DsRed in neurons, and scored for colocalization events in response to NMN treatment. Similar to mtRosella, NMN promotes colocalization of DCT-1 and the LGG-1-labeled autophago-somes, indicating neuronal mitophagy elevation (Fig. 2b,c). Next, we tested a panel of compounds using our in-house small compound library as well as known autophagy/mitophagy inducers. This screen identified two potent neuronal mitophagy-inducing agents, urolithin A (UA), a small natural compound prominent in pomegranate that induces mitophagy in muscles26, and actinonin (AC), an antibiotic that induces in vitro mitophagy via a specific mitochondrial ribosomal and RNA decay pathway27 (Fig. 2a–c). To investigate the molecular mechanisms by which UA and AC induce neuronal mitophagy, we treated human neuronal SH-SY5Y cells with UA and AC, respectively, at doses ranging from 10 to 100 μM. UA increased the protein levels of a series of mitophagy-related proteins, including full-length PINK-1 (F-PINK-1), parkin, beclin-1, Bcl2L13, AMBRA1, and p-ULK1(Ser555) (Supplementary Fig. 3a). In vivo, UA increased F-PINK1 in an APP/PS1 mouse model (Supplementary Fig. 3b). AC exhibited very similar effects to UA (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). Consistently, in WT nematodes, NMN-, UA-, and AC-induced neuronal mitophagy was dependent on key mitophagy genes, dct-1, pdr-1, and pink-1 (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2). Altogether, our data suggest that NMN, UA, and AC induce robust neuronal mitophagy through the evolution-arily conserved mitophagy machinery.

Fig. 2 |. Mitophagy induction restores memory in Aβ1–42 C. elegans model of AD.

a, Transgenic animals expressing the mtRosella biosensor in neuronal cells were treated with NMN, UA, and AC. Relative levels of neuronal mitophagy are expressed as the ratio between pH-sensitive GFP fluorescence intensity and pH-insensitive DsRed fluorescence intensity. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 35 nematodes per group; ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple-comparisons test). VEH, vehicle. b, Transgenic nematodes were treated with NMN, UA, and AC. Mitophagy events were calculated by the colocalization between the autophagic marker DsRed::LGG-1 and the mitophagy receptor DCT-1::GFP in neurons. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 18–20 neurons per group as detailed in the figure; ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple-comparisons test). c, Representative images of b; scale bars, 5 μm. d, Transgenic nematodes expressing the mtRosella biosensor in neuronal cells treated with NMN, UA, and AC. The decreased GFP/DsRed ratio of mtRosella indicates neuronal mitophagy stimulation. DCT-1, PDR-1, and PINK-1 were required for neuronal mitophagy induction in response to UA, NMN, and AC treatment. The center value represents mean and error bars represent s.e.m. (n = 32–102 nematodes per group as detailed in the figure; NS (not significant), P > 0.05, and ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple comparisons test). e,f, Nematodes expressing Aβ1–42 display decreased basal levels (e) and reserve capacity (f) of OCR. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 3 independent experiments; ***P < 0.001; two-sided Student’s t test). g, Mitophagy events were reduced in the neuronal cells of Aβ1–42-expressing nematodes under control and oxidative stress (paraquat/paraquat 8 mM) conditions. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 26–27 neurons per group as detailed in the figure; NS, P > 0.05 and ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple-comparisons test). h, Aversive conditioning (to isoamyl alcohol in the absence of food) is impaired in transgenic animals expressing Aβ1–42 (CL2355 strain) in neurons. The bars depict the chemotaxis indices toward isoamyl alcohol, monitored for either naïve or conditioned WT and Aβ1–42-expressing nematodes. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 400 nematodes per group; ***P < 0.001; two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test). i, Dietary supplementation with UA, NMN, or AC improves associative memory in transgenic nematodes expressing Aβ1–42 (CL2355 strain). The bars depict the chemotaxis indices toward isoamyl alcohol, measured for either naïve or conditioned WT and Aβ1–42-expressing nematodes with or without UA, NMN, or AC treatment. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 400 nematodes per group; ***P < 0.001; two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test). Experiments for the data in h and i were performed together and thus share the same data for the VEH groups. j. UA reduces Aβ peptides in CL2355 nematodes (day 5). The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 7 biologically independent samples in the VEH group or 8 biologically independent samples in the UA-treated group; *P < 0.05; two-sided Student’s t-test). For all nematode experiments, two to four independent experiments were performed.

To determine the respective contribution of mitophagy and the more general macroautophagy in our study, we compared doses of NMN (5 mM), UA (0.1 mM), and AC (1 mM), which we found to induce robust neuronal mitophagy (Fig. 2a–c). Under these conditions, we found no detectable changes in macroautophagy. NMN (5 mM), UA (0.1 mM), and AC (1 mM) did not induce neuronal mac-roautophagy in nematodes expressing the autophagosomal protein LGG-1 fused with either GFP or DsRed (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). We examined additional autophagy markers, such as LGG-1, LGG-2, and ATG-18 (Atg18 protein homolog/WD repeat domain phos-phoinositi de-interacting protein 1), fused with GFP upon NMN (5 mM), UA (0.1 mM), and AC (1 mM) supplementation in several tissues and found that general macroautophagy was not induced in nematode embryos, and nematode intestinal, muscle, and neuronal cells (Supplementary Fig. 4c–h). In conclusion, the optimized doses of NMN (5 mM), uA (0.1 mM), and AC (1 mM) specifically induce mitophagy, not macroautophagy, in nematodes.

To investigate the contribution of neuronal mitophagy to AD pathophysiology, we took advantage of the already established models of AD in C. elegans28,29. Transgenic nematodes expressing pan-neuronal human Aβ1–42 (CL2355) protein displayed defective energy metabolism defined by a lower oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and reduced mitophagy under normal and stress (paraquat treatment) conditions (Fig. 2e–g, and Supplementary Fig. 3c). Progressive memory impairment is the most common symptom in AD patients2,30; therefore, we evaluated memory in the AD C. elegans models using an aversive olfactory learning chemotaxis assay (a negative value correlates with chemotaxis-related memory)31. Transgenic nematodes expressing Aβ1–42 (CL2355) showed severe cognitive defects (Fig. 2h). Mitophagy induction with NMN, UA, or AC improved the memory of transgenic nematodes (CL2355) without influencing the memory of WT animals (Fig. 2i). To elucidate the mechanism by which mitophagy enables memory improvement, and to exclude off-target responses, we examined the associative memory of mitophagy-deficient nematodes expressing human Aβ1–42. We generated three mitophagy mutant Aβ strains: pink-1(tm1779);CL2355, pdr-1(gk488);CL2355 and dct-1(tm376);CL2355. Interestingly, depletion of PINK-1 and Parkinson’s disease related-1 (PDR-1; the mammalian homologs of PINK1 and parkin, respectively) abolished the beneficial effects of UA and AC, whereas DCT-1 (the nematode BNIP3 and BNIP3L/NIX) was dispensable (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d). The neuronal mitophagy induction in response to NMN, UA, or AC supplementation required PINK-1 and PDR-1, while the NMN-induced memory increase was dependent on DCT-1 function (Supplementary Fig. 5). This could be explained by the previously reported direct elevation of DCT-1 protein levels on NMN treatment through the NAD+/SIR-2.1-DAF-16 pathway12. Additionally, UA reduced whole-body Aβ levels in CL2355 nematodes (Fig. 2j). Collectively, these findings indicate that compromised mitophagy, combined with excessive mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to a chemotaxis defect in AD nematodes. Pharmacological stimulation of mitophagy improved the chemotactic index in transgenic Aβ1–42 animals.

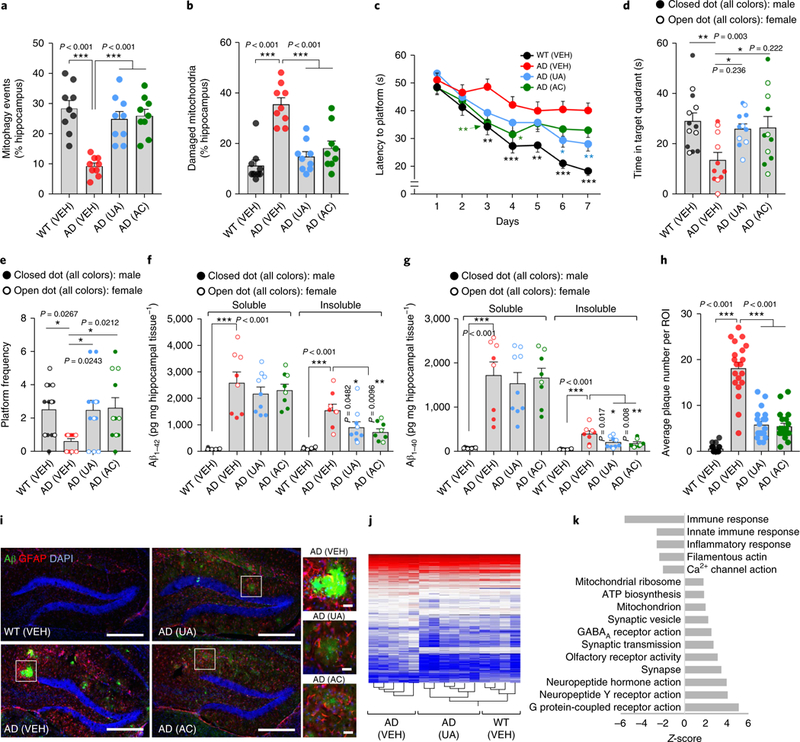

Restoration of neuronal mitophagy ameliorates cognitive decline and Aβ pathology in the APP/PS1 mouse model.

To investigate the protective role of mitophagy against memory loss and its conservation across species, we monitored the effects of UA and AC in the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of AD. Transgenic AD mice were treated orally with UA (200 mg/kg/day) or AC (30 mg/kg/day) for 2 months and subsequently examined behavioral and molecular end points. In congruence with the C. elegans results, electron micros-copy analysis indicated that UA and AC administration stimulated mitophagy and promoted the elimination of defective mitochondria in the hippocampus of AD mice (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Fig. 6a). UA and AC also normalized mitochondrial morphology and size in the hippocampus of AD mice (Supplementary Fig. 6b). We further verified the improvement of mitophagy and mitochondrial metabolism in isolated hippocampal neurons from the 2-month UA-and AC-treated AD mice (Supplementary Fig. 6c–e). Using the classical Morris water maze (MWM) test, both UA and AC greatly improved learning and memory retention in the AD mice with no difference in swimming speed between groups (Fig. 3c–e and Supplementary Fig. 7a,b). The treatments normalized memory retention in the AD mice to that of the WT mice (Fig. 3d,e). Mitophagy stimulation also improved spatial memory in the Y maze spontaneous alternation behavioral test (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Several common features of AD pathology, including insoluble levels of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40, and extracellular Aβ plaque burden (Fig. 3f–i) were diminished on UA and AC treatment. While astro-cytic activation, measured by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) levels, was increased in the vehicle (VEH)-treated AD mice compared with VEH-treated WT mice, UA or AC did not reduce the GFAP signal in the AD mice (Fig. 3i, and Supplementary Fig. 7d). We also analyzed the impact of the mitophagy-inducing compounds on the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of WT and AD mice. Supplementation with UA or AC resulted in the reduction of soluble Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 whereas the insoluble forms remained unchanged (with a trend toward decrease) in the PFC of AD mice (Supplementary Fig. 7e,f). Consistently, UA or AC promoted mitophagy, eliminating damaged mitochondria and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in the PFC region of AD mice (Supplementary Fig. 6f–h). To further investigate whether mitophagy induction indeed improves Mitochondrial function in AD, we performed OCR evaluation in APOE4/E4 iPSC-derived neurons. UA (24h) treatment significantly increased the maximal OCR of APOE4/E4 neurons, compa-rable with that of WT (VEH) neurons (supplementary Fig. 6i). We confitmed that mitophagy induction increased OCR and reduced mitochondrial ROS in Aβ1–42(CL2355) nematodes (Supplementaty Fig. 6j–1). Collectively, these findings in transgenic nematodes, iPSC-derived neurons, and mouse models of AD suggest a con-served neuroprotective role of mitophagy across species against AD pathology and cognitive deficits.

Fig. 3 |. Mitophagy induction ameliorates Aβ pathology and cognitive decline in APP/PS1 AD mice.

APP/PS1 mice were treated with UA (200 mg kgday−1) or AC (30 mg kgday−1) by daily gavage for 2 months starting from 6 months of age; then, behavioral tests were performed and brains were subjected to histological and molecular analyses. a,b, Electron microscopy analysis shows that hippocampal neurons in UA- and AC-treated AD mice display increased mitophagy-like events (a) and removal of damaged mitochondria (b). Center values represent means and the error bars represent s.e.m. (n = 9 random fields from 3 mice; ***P< 0.001; one-way ANOVA). c, Latency to escape to a hidden platform in the MWM during a 7-d training period. Day 3: WT versus AD (VEH), P = 0.0010; AD (VEH) versus AD (AC), P = 0.0052. Day 4: WT versus AD (VEH), P = 0.0006; AD (VEH) versus AD (AC), P= 0.0317. Day 5: WT versus AD (VEH), P= 0.0063. Day 6: WT versus AD (VEH), P< 0.0001; AD (VEH) versus AD (UA), P = 0.0137. Day 7: WT versus AD (VEH), P< 0.0001; AD (VEH) versus AD (UA), P= 0.0060 (n = 13 mice in the WT (VEH) group, or n = 11 mice in all the other groups; *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001; two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test). d,e, Further analysis of the MWM test; time in the target quadrant in the probe trial (d) and number of times mice passed through the platform location in the probe trial (e). The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 13 mice in the WT (VEH) group or n = 11 mice in all the other groups; *P<0.05, **P< 0.01; one-way ANOVA). f,g, Soluble and insoluble Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 levels in hippocampal tissues. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 9 mice in the AD UA group; n = 8 mice in all the other groups; *P<0.05, **P< 0.01; one-way ANOVA). h, The number of Aβ plaques is decreased on UA and AC treatment in the hippocampus. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 20 random areas in the ROIs from 3 mice; ***P< 0.001; one-way ANOVA). i, IHC of amyloid plaques (6E10 antibody), astrocytes (GFAP antibody), and DAPI. Scale bar, 200 μm; insets: scale bar, 20 μm. The experiments were repeated twice independently with similar results. j, Heat map of differentially expressed genes as determined by microarray of hippocampal tissues. k, Transcriptomic analysis of GO pathways between AD (UA) and AD (VEH). Error bars show±s.e.m. j,k, n = 5, 6, and 4 mice for AD (VEH), AD (UA), and WT (VEH), respectively.

To obtain a systematic, unbiased overview of how mitophagy induction affects memory-related neuronal function in AD, we performed genome-wide transcriptomic analysis of hippocampal tissue from WT and AD mice with or without UA treatment. Heat map clustering analysis of differentially expressed genes indicated that UA restores the transcriptomic profile of AD transgenic mice toward that of WT mice (Fig. 3j). Consistent with previous reports in AD, gene set enrichment analysis of AD (VEH) mice revealed major changes in the expression level of genes associated with inflammation and neuronal function (Supplementary Fig. 8)2,30. For example, Gabra2 (involved in GABAergic neurotransmission and Aβ clearance), Lrrtm4 (involved in excitatory synapse development), Slitrkl (participates in synapse formation), and Lgi2 (involved in synapse remodeling) were downregulated in the AD (VEH) mice; however, UA treatment increased the messenger RNA expression of these genes (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Further pathway analysis supports that UA treatment upregulates multiple signaling pathways related to neuronal protection and memory benefits, including ATP biosynthesis, GABAa receptor activity, and synapse and neuropeptide activities among others, whereas it inhibits inflammatory responses (Fig. 3k, Supplementary Fig. 8b, and Supplementary Table 2). Notably, UA and AC significantly increased synaptophy-sin levels by over 3.5-fold, indicating an increase in synapse numbers (Supplementary Fig. 7g). Because synaptic failure is the major driver of memory loss in AD32, our results suggest that mitophagy inhibits memory loss in AD mice through the maintenance of synapses in addition to neuronal function.

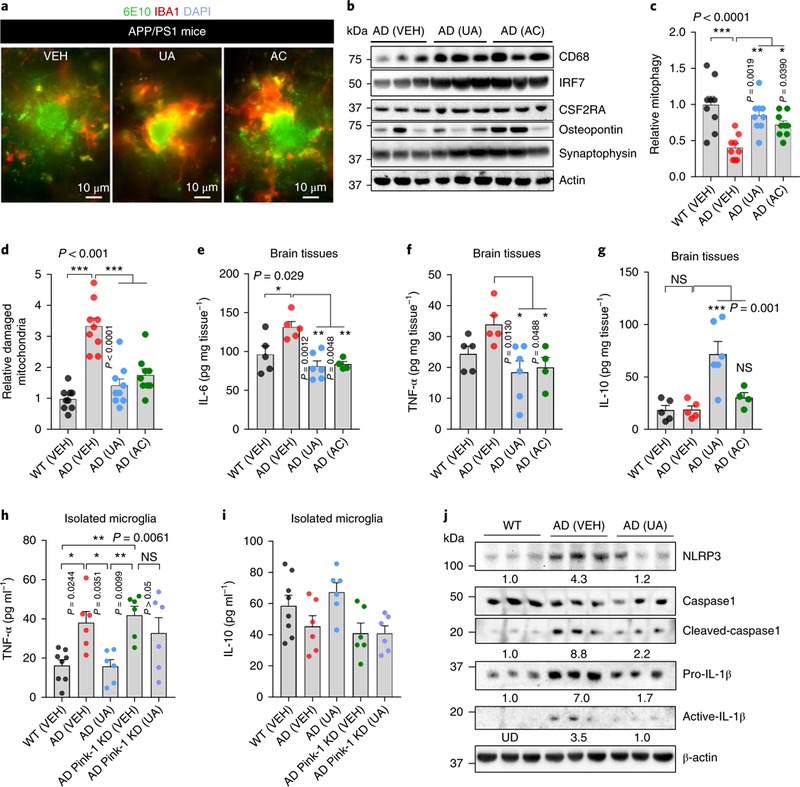

Restoration of neuronal mitophagy enhances the phagocytic efficiency of microglia and mitigates neuroinflammation.

Aβ plaque e formation is the consequence of an imbalance between Aβ clearance and its production from proteolytic cleavage of APP30. Supplementation with UA did not alter the levels of APP cleavage intermediates, including N-terminal fragments (NTFs) and C-terminal fragments (CTFs), in the hippocampus of transgenic AD animals (Supplementary Fig. 7h). AC treatment reduced CTFs while no significant effect on the APP NTFs was observed (Supplementary Fig. 7h). Thus, we investigated whether there was enhanced Ap plaque removal on pharmacological mitophagy induction. Microglia are the primary immune and phagocytic cells of the central nervous system. They play a crucial role in the clearance of extraneuronal Aβ plaques, which impact AD development and progression30,33. Therefore, we evaluated whether mitophagy stimulation influences microglial activity, and whether increased microglial activity could enhance the removal of Aβ plaques. Indeed, we observed increased engulfment of Aβ plaques by microglia in response to AC and UA treatment (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 7j). UA (but not AC) supplementation resulted in an increased microglial population (Supplementary Fig. 7j). Further, UA- and AC-treated animals displayed a decreased number and length of microglial processes highlighting their shift toward a phagocytic state (Supplementary Fig. 7j)30. In accord with this, mitophagy induction increased the expression of the engulfment-associated protein cluster of differentiation 68 (CD68), microglia-enriched transcriptional regulator interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7), and the microglia proliferation marker cluster of differentiation 116 (CD116/CSF2RA), without changing the levels of osteopontin, a cell adhesion and migration regulator (Fig. 4b and quantification in Supplementary Fig. 7g). Mitophagy in microglial cells was decreased by 60% in the hippocampus of AD mice compared to WT (Fig. 4c), and there were more damaged mitochondria in AD microglia cells than in WT (Fig. 4d). UA and AC treatments normalized mitophagy in AD microglia and decreased the extent of mitochondrial damage (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Fig. 7i). Phagocytosis requires large amounts of energy, which is mainly derived from mitochondria. Therefore, our results suggest that mitophagy induction increases the efficiency of phagocytosis of Aβ plaques by microglia through balanced mitochondrial homeostasis providing the required energy.

Fig. 4 |. Mitophagy induction promotes phagocytic activity of microglia and inhibits neuronal inflammation in APP/PS1 AD mice.

a, Representative images showing microglial cells engulfing or near Aβ plaques. Aβ plaques are shown in green (6E10 antibody) and microglia (anti-lbal antibody) are in red. b, Effects of UA and AC on the expression level of proteins involved in microglial phagocytosis and synaptic function in the hippocampus (n = 3 mice per group). c,d, Electron microscopy data show elevation of mitophagy-like events (c) and diminished mitochondrial damage (d) in response to UA and AC administration. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 3 mice per group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P< 0.001; one-way ANOVA). e-g, The levels of the indicated cytokines were altered on UA- and AC-induced mitophagy. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 5 mice in WT (VEH), n = 5 mice in AD (VEH), n = 6 in AD (UA), and n = 4 in AD (AC); NS, P> 0.05 and *P<0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001; one-way ANOVA). h,i, UA inhibits inflammation in microglia isolated from APP/PS1 mice via PINK-1-dependent mitophagy. CD11b+, CD45low microglial cells were isolated from the brain tissue of WT and APP/PS1 mice through a FACS sorting system. Cells were then cultured to knock down Pink1, followed by the treatment of UA (50μM for 24h). Cytokines were detected using commercial ELISA kits. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 8 mice in the WT (VEH) group, or n = 6 in the other groups; *P< 0.05; one-way ANOVA). j, Western blot data showing the effects of UA on the expression levels of proteins involved in NLRP3 inflammasome activity and inflammation in the cortical tissue of the mice (n = 3 mice per group). Numbers inserted are the mean of the average protein level per 3 samples; UD, undetected. Tissues/cells from 8-month- old mice were used for the experiments. Full scans of all the blots are in the Supplementary Note.

While essential for the removal of Aβ plaques, microglia also contribute to local neuroinflammation that causes neurotoxicity and disease progression30,33. Microglia often exist in an activated state and produce proinflammatory cytokines in AD mice34. Therefore, we examined whether mitophagy-inducing compounds affect the levels of neuroinflammation in APP/PS1 AD mice. UA and AC reduced the protein levels of several key proinflamma-tory cytokines including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; Fig. 4e,f). The IL-10 anti-inflammatory cytokine was recently found to promote mitophagy in primary macro-phages35. Interestingly, treatment with UA increased IL-10 levels in hippocampal tissue fourfold (Fig. 4g). Inflammation data were generated using brain tissues, where the interpretation of a direct role of mitophagy induction in the reduction of microglia-related inflammation was limited. To address this concern, we isolated microglia from the brain tissues of WT and APP/PS1 mice, followed by small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of Pink1 in AD microglia. In this pure microglia culture system, depletion of Pink1 increased the expression of the inflammatory marker TNF-α and almost completely eliminated UA-induced inhibition of TNF-α, with a similar non-significant trend for IL-10 (Fig. 4h,i). To investigate the intrinsic mechanisms of this mitophagy enhancement and inflammation, we examined the activity of the NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which was reported to be activated in AD mice and whose activation promotes AD36. We found elevated expression of NLRP3 and increased expression of cleaved caspase 1 in the brain tissues of AD mice, indicating an increase in the activity of NLRP3. In UA-treated APP/PS1 mice, the expression and activity of NLRP3 were reduced as evidenced by lower levels of its downstream proteins, including cleaved caspase 1, proinflammatory IL-1β, and active IL-1β (Fig. 4j). These findings, combined with the reduced insoluble Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 protein levels noted earlier in the hippocampus of transgenic APP/PS1 AD mice, indicate that mitophagy stimulation enhances the phagocytic efficiency of microglia, while at the same time mitigating NLRP3/ caspase-1-dependent neuroinflammation.

Restoration of neuronal mitophagy ameliorates p-tau pathology and cognitive deficits in AD across species.

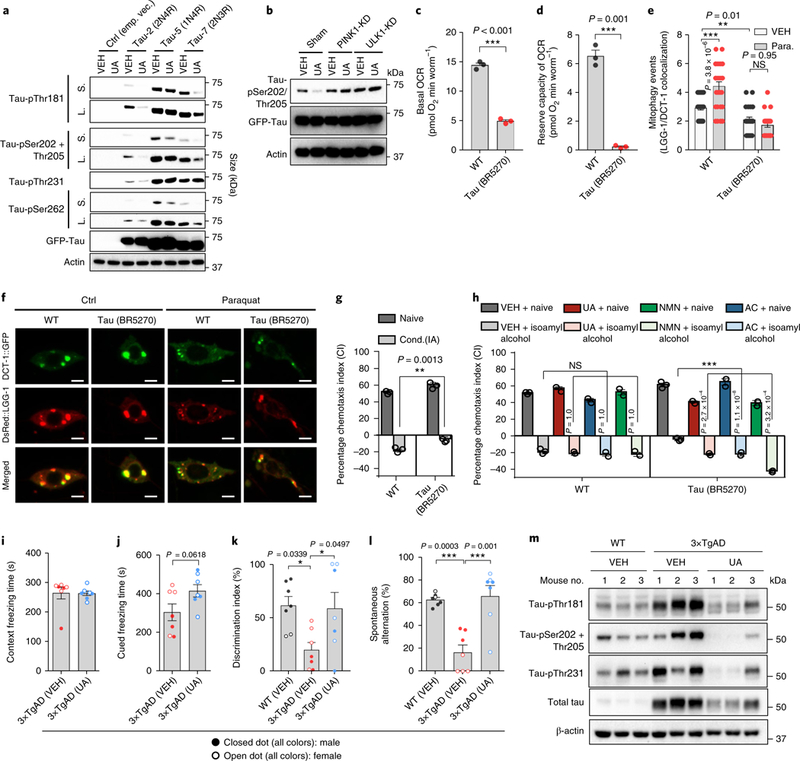

Amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are hallmark features of AD pathology. In AD transgenic mice, the abnormal accumulation of Aβ peptides instigates the formation of extracellular amyloid plaques, whereas intraneuronal aggregation of p-tau proteins generates neurotoxic tau tangles leading to defective axonal transport of mitochondria and synaptotoxicity6,37. Several p-tau sites, such as Thr181, Ser202/ Thr205, Thr231, and Ser262 are considered possible clinical biomarkers of AD in human patients37,38. Thus, we examined whether mitophagy-inducing compounds regulate p-tau. UA treatment inhibits phosphorylation of many of the p-tau sites (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 9a). UA inhibited p-tau in a mitophagy-depen-dent manner as the effect was diminished in PINK1 knockdown and ULK1 knockdown cells (Fig. 5b). We then investigated the effects of mitophagy induction in a tau worm model (BR5270) with pan-neuronal expression of the pro-aggregant F3ΔK280 tau fragment28. This tau (BR5270) nematode strain shows severe mitochondrial dysfunction as indicated by 70% decrease of its basal OCR and loss of reserve capacity relative to WT (Fig. 5c,d). Moreover, both basal and stress-induced (paraquat treatment) mitophagy events were decreased in the tau (BR5270) nematodes (Fig. 5e,f). Importantly, memory loss in the tau (BR5270) nematodes was restored by pharmacological stimulation of mitophagy (Fig. 5g,h). To verify that memory retention is dependent on mitophagy in AD, we generated three mitophagy mutant tau strains: pink-1(tm1779);BR5270, pdr-1(gk488);BR5270 and dct-1(tm376);BR5270. While NMN-induced memory retention in the BR5270 nematodes was dependent on PINK-1, PDR-1, and DCT-1, UA was dependent on PINK-1 and PDR-1, and AC was only PINK-1-dependent (Supplementary Fig. 9b–e). In addition, UA-induced mitophagy induction reduced mitochondrial ROS in the BR5270 nematodes (Supplementary Fig. 6l).

Fig. 5 |. Mitophagy induction inhibits tau hyperphosphorylation in human neuronal cells and enhances memory in a tau C. elegans model and a 3×TgAD mouse model.

a, Levels of p-tau in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells overexpressing 2N4R, 1N4R, 2N3R tau, or empty vector, which had been treated for 24 h with either VEH or 50 μM UA. S, short exposure; L, long exposure of the same blot. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results. b, UA-induced inhibition of p-tau at Ser202/Thr205 is dependent on PINK-1 and ULK1. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results. c,d, Nematodes expressing tau present decreased basal levels (c) and reserve capacity (d) of OCR. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 3 independent experiments; ***P < 0.001; two-sided Student’s t test). e, Mitophagy events are reduced in neurons of tau-expressing nematodes under normal and oxidative stress (paraquat/paraquat 8 mM) conditions. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 30 neurons per group; NS, P > 0.05 and ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple comparisons). The experiments for this panel and Fig. 2g were performed together with the same WT control. f, Representative images of mitophagy events in WT and tau (BR527 strain) nematodes under normal and oxidative stress conditions (paraquat/paraquat 8 mM) in neurons. Colocalization of the mitophagy receptor DCT-1::GFP and the autophagosomal protein DsRed::LGG-1 indicates mitophagy events. Scale bars, 2 μm. g, Conditioning (cond.) to isoamyl alcohol in the absence of food is impaired in transgenic nematodes expressing human tau (BR5270 strain) in neurons. The bars depict the chemotaxis indices toward isoamyl alcohol, monitored for either naïve or conditioned WT and tau-expressing nematodes. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 400 nematodes per group; ***P < 0.001; two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test). h, Supplementation of UA, NMN, or AC improves memory in transgenic animals expressing tau (BR5270 strain). The bars depict the chemotaxis indices toward isoamyl alcohol, measured for either naïve or conditioned WT and tau-expressing nematodes with or without UA, NMN, or AC treatment. The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 400 nematodes per group; ***P < 0.001; two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiplecomparisons test). The experiments for g were performed together with h; thus, they share the same data for the VEH group. i–l, Treatment with UA for 1 month improves memory performance and inhibits p-tau in 3× TgAD mice. Thirteen-month-old 3× TgAD mice were treated with UA (200 mg kg day−1) by daily gavage for 1 month. Contextual and cued fear conditioning (i,j), object recognition (k), and Y-maze (l) tests were performed. i–l, The center value represents the mean and the error bars represent the s.e.m. (n = 7; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001; a two-sided Student’s t test was used for i and j, while one-way ANOVA was used for k and l). m, A western blot was used to evaluate changes of designated p-tau sites using hippocampal tissues from killed mice (n = 3). All error bars ± s.e.m. Full scans of all the blots are in the Supplementary Note.

To test the conserved beneficial role of mitophagy induction in p-tau, we next performed a one-month UA treatment protocol in the 3×TgAD mice. We first performed a contextual and cued fear conditioning test to assess learning and memory of an association between environmental cues and aversive experiences39. While there was no difference in context freezing time, UA affected a trend of increased cued freezing time in the 3×TgAD mice (Fig. 5i,j). Intriguingly, both object recognition and Y maze tests indicated normalization of performance by UA in the 3×TgAD mice to that of WT (VEH) mice (Fig. 5k,l). At the molecular level, UA showed strong p-tau inhibition at sites including Thr181, Ser202/Thr205, and Ser262 (Fig. 5m), similar to its function in the tau-overexpressed human SH-SY5Y cells. Because sex is a biological variable in AD40, we investigated whether there were sex differences in the responses to the mitophagy inducers in both APP/PS1 and 3×TgAD mice. While UA appeared to be more potent toward male than female APP/PS1 mice, it showed similar effects in male and female 3×TgAD mice (Supplementary Fig. 10). Because of the small group sizes in each sex of mice, future studies are necessary to gain full insight into sex differences. Altogether, our observations strongly indicate that mitophagy induction inhibits phosphorylation of tau protein, resulting in memory improvement in both C. elegans and mouse models of tauopathies.

Discussion

Our cross-species analysis provides evidence that mitophagy defects have a critical role in AD development and progression. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a common pathological feature and contributes to neurodegeneration in both transgenic animal models and human AD patients2,41. Impairment of mitochondrial proteosta-sis and exhaustion of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD4. Diverse changes of mitophagy in AD in different systems have been reported42,43. Our results suggest that impaired initiation of selective mitochondrial autophagy, due to decreased levels of activated mitophagic proteins, such as p-TBK1 and p-ULK1, results in the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and impaired cellular energy metabolism. We demonstrate that defective mitophagy, which can be caused by both Aβ1–42 and p-tau, is a major element of AD progression and memory loss in a manner that is conserved from C. elegans and mice to humans. Defective mitophagy and mitochondrial dysfunction hampers ATP production, which induces AMPK activation (p-AMPK). AMPK activation often leads to excessive mitochondrial fission14 and further reduces ATP production in a vicious cycle. Hyperactivation of p-AMPK induces tau phosphorylation, which is critical for the synaptotoxic effects of Aβ1–42 oligomers6. Interestingly, several reports show that Aβ1–42 oligomers can activate AMPK in a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2-dependent manner in neurons44,45, which may further exacerbate cellular levels of p-tau. Further studies to uncouple the interconnected sophisticated roles between defective mitophagy, AMPK, p-tau, and Aβ in AD etiology and progression are necessary. A working model is proposed (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Our findings extend the ‘AD mitochondrial cascade hypothesis’2,41 through the linkage of defective mitophagy to damaged mitochondria. First, we show that Aβ inhibits mitophagy while mitophagy induction reduces Aβ. Second, we show that tau impairs mitophagy while mitophagy stimulation inhibits several common p-tau sites. However, they also raise many important questions, such as: (1) the chronological sequence of defective mitophagy, Aβ, and tau tangles; (2) whether defective mitophagy and AD pathologies exacerbate one another; and (3) whether any sex differences in mitophagy exist in AD patients since the prevalence of AD and other dementias is higher in women than in men40. While it is difficult to address these questions with the current transgenic AD animal models, other animal models more similar to human AD, as well as human longitudinal studies, may provide an insight.

In mammals there are multiple mitophagy pathways suggesting that dysfunction of one can be compensated by others2,16. In AD defects in mitophagy (as evaluated in this study) and autophagy19 may occur at different steps within these pathways. We found that three distinct pharmacological approaches were effective in counteracting the pathogenic processes of AD and ameliorating cognitive impairment, suggesting a potential for clinical interventions that enhance mitophagy via different mechanisms. For example, BNIP3L/NIX/DCT-1 serves as a mitophagy receptor mediating the clearance of damaged mitochondria and ensures stress resistance and healthy aging2,10. Interestingly, some AD patients display reduced levels of BNIP3L/NIX (indicating mitophagy defects). Although NMN-induced memory enhancement depends on DCT-1 functionality, AC- and UA-induced memory improvement was independent of DCT-1 and can thus be beneficial when BNIP3L/NIX function is compromised. Our findings provide a pharmacological approach to optimize and overcome deficits in different mitophagy pathways, thereby ameliorating the cognitive impairments characteristic of both Aβ and tau pathologies.

An interconnected network between neurons and supporting glial cells, including microglia, maintains brain homeostasis. Our findings suggest that the accumulation of damaged mitochondria and compromised mitophagy influence not only neurons but also microglia in AD. Microglia play a pivotal role in the removal of neurotoxic proteinaceous components and simultaneously release proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines that regulate immune responses46. In APP/PS1 mice, we show the accumulation of damaged mitochondria and defective mitophagy in microglia, leading to impaired efficacy of phagocytic clearance of Aβ plaques. Hence, mitophagy restoration promotes the elimination of dysfunctional organelles and enhances microglial phagocytic capacity (Supplementary Fig. 11). Importantly, microglia exhibit confounding roles in AD, including protective functions (for example, phagocytosis)30,33 and detrimental effects (for example, release of inflammatory cytokines and related cross-seeding of Aβ)46,47. Our study unveils a previously unexplored function of mitophagy that coordinates both phagocytosis and anti-inflammation in microglia. At the molecular level, both PINK148 and parkin49 have been shown to play important roles in the improvement of mitochondrial function and the elimination of intracellular Aβ in AD mice. Our study extends the importance of the PINK1-dependent pathway to the elimination of proinflamma-tory cytokines by AD microglia. More broadly, by providing evidence of a protective role for mitophagy in neurons and microglia, the current study raises the possibility that mitophagy induction is also beneficial to other glial cells as well as other non-neuronal cells. Emerging evidence suggests that AD affects not only the brain but also peripheral tissues50. Thus, targeting the maintenance of mitochondrial quality at both neuronal and organismal levels may be a promising therapeutic approach.

Methods

C. elegans strains and genetics.

Standard C. elegans strain maintenance51,52 procedures were followed. The nematode rearing temperature was kept at 20 °C, unless otherwise noted. The following strains were used in this study. N2: wild-type Bristol isolate, pink-1(tm1779)II, dct-1(tm376)X,VC1024: pdr-1(gk448)III, CL2241: dvIs50 [Psnb-1Abeta 1–42; rol-6(su1006)], CL2355: dvIs50 [Psnb-1Abeta 1–42; Pmtl-2GFP] I,BR5270: byIs161[prab-3F3ΔK280; pmyo-2mCherry], dvIs50[Psnb-1Abeta 1–42;Pmtl-2GFP] I; pink-1(tm1779)II, dvIs50[Psnb-1Abeta 1–42;pmtl-2GFP]I;dct-1(tm376)X, dvIs50[Psnb-1 Abeta 1–42;Pmtl-2GFP]I;pdr-1(gk448)III, pink-1(tm1779)II;byIs161[Prab-3F3ΔK280; Pmyo-2mCherry], dct-1(tm376)X;byIs161 [Prab-3F3ΔK280; pmyo-2mCherry], pdr-1(gk448)III; byIs161[Prah-3F3ΔK280-;pmyo-2mCherry]. To monitor neuronal mitophagy, we used IR1864: N2; Ex001[punc-119T0MM-20::Rosella] transgenic animals. To examine DCT-1 and LGG-1 interaction in vivo in neurons, we used the following transgenic animals: IR2160: N2; Ex002 [prab-3DsRed::LGG-1;prab-3DCT-1::GFP; Pmyo-2GFP], IR2162: N2; byIs161[Prab-3F3ΔK280;pmyo-2mCherry]; Ex002[prab-3DsRed-LGG-1; prab-3DCT-1-GFP; Pmyo-2GFP], IR2161: N2; dvIs50[pSnb-1Abeta1–42; rol-6(su1006)]; Ex002 [prab-3DsRed-LGG-1; prab-3DCT-1::GFP; Pmyo-2GFP]. To monitor neuronal autophagy, we used IR308: N2; Ex001 [Pmec-7GFP-LGG-1; rol-6(su1006)] and IR2379: N2; Ex010[Prab-3DsRed::LGG-1] transgenic animals. To monitor general autophagy, we used the following transgenic animals: VIG9: unc119(ed3)III; Is[unc-119(+);Plgg-2GFP::LGG-2], DA2123: N2; adIs2122 [plgg-1GFP-LGG-1; rol-6(su1006)] and MAH145: N2; sqEx4[Patg-18ATG-18::GFP; rol-6(su1006)].

Molecular cloning.

To generate the prab-3DCT-1::GFP reporter construct, we fused a BglII fragment, containing the coding sequence of DCT-1::GFP, amplified from the pdct-1DCT-1::GFP reporter construct using the primers 5’ AGATCTATGTCCATCTTTCTTGAGTTTG 3’ and 5’ AGATCTCTATTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGC 3’, downstream of the mec-7 promoter in the pPD96.41 plasmid vector. Then we removed the mec-7 promoter and inserted a SphI/XmaI fragment containing the rab-3 promoter, amplified from the C. elegans genomic DNA using the primers 5’ GCATGCATTTGCTTCTATTCCGTCCT 3’ and 5’ ACCGGTCCCGGGCTGAAAATAGGGCTACTGTAGAT 3’, upstream of DCT-1::GFP. To generate prab-3DsRed-LGG-1, we inserted an AgeI/EcoRI fragment (derived from plgg-1DsRed::LGG-1), containing the coding sequence of DsRed downstream of the mec-7 promoter of the pPD96.41 plasmid vector. We then fused an EcoRI fragment (derived from plgg-1DsRed::LGG-1) containing the coding sequence of lgg-1 at the DsRed C terminus of pmec-7DsRed. Then we removed the mec-7 promoter and inserted a SphI/AgeI fragment containing the rab-3 promoter. The translational prab-3DCT-1::GFP and prab-3DsRed::LGG-1 fusion constructs were co-injected with the pmyo-2GFP transformation marker into the gonads of WT animals. To generate punc-119TOMM-20::Rosella, we removed the myo-3 promoter form pmyo-3T0MM-20::Rosella described previously10 and we inserted an HindIII/Xbal fragment (derived from punc-119CTS-1::mCherry10) containing the unc-119 promoter upstream of the coding sequence of the TOMM-20::Rosella biosensor. The translational punc-119TOMM-20::Rosella fusion construct was co-injected with pRF4 (rol-6(su1006) dominant transformation marker) into the gonads of WT animals.

Screening of neuronal mitophagy inducers.

Neuronal mitophagy inducers were screened using two mitophagy detection nematode lines, Ex[punc-119mtRosella] and Ex[prab-3DCT-1:GFP;prab-3DsRed::LGG-1]. Our small compound library consists of small compounds for AD treatment synthesized in-house (by N. Greig, National Institutes of Health) and commercially available known autophagy/mitophagy inducers. For the in vivo drug screening, NMN was used as the positive control while the solvent (1% dimethylsulfoxide) was used as the negative control. Neuronal mitophagy events were quantified using the z-scores of the colocalization between LGG-1 and DCT-1. A screening window coefficient, called Z-factor, was used for evaluation and validation; a z-score of 0.5–1.0 means that the drug screen is deemed acceptable23. An agent with values higher than WT (P < 0.05) was scored as a mitophagy inducer.

C. elegans memory assays.

Chemotaxis to volatile compounds was performed at 25 °C, on 9 cm agar plates as described previously31,53. The chemotaxis index was calculated by subtracting the number of animals found at the trap from the number of animals at the source of the chemical, divided by the total number of animals subjected to the assay31. The resulting values were expressed as percentiles. For conditioning to isoamyl alcohol, a droplet of 5 μl pure isoamyl alcohol was placed on the lid of a conditioning non-bacterial seeded nematode growth medium plate. Animals were conditioned to isoamyl alcohol for 90 min. Both naïve and conditioned animals were exposed for 90 min to isoamyl alcohol (gradient sources: isoamyl alcohol, 1:100 dilution in water). One-day-old adult hermaphrodites were used in the behavioral assays. Three distinct populations of 300–400 adults (for each strain) were scored during the assay period. For all experiments, NMN (5 mM) and AC (1 mM) nematodes were treated for two generations, while UA (0.1 mM) nematodes were treated from eggs for one generation. Two to four technical replicates were performed for all nematode experiments.

Mitophagy/autophagy detection.

Mitophagy was detected in multiple model organisms using several methods as reported previously10,12,24,54. Postmortem hippocampal brain tissue samples of AD patients and sex- and age-matched healthy controls were obtained from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (n = 7 per group; https://hbtrc.mclean.harvard.edu/), and mitophagy was evaluated using electron microscopy (by a US-certified electron microscopist), western blot analysis, and the colocalization between Tom20 antibody (1:500 dilution; catalog no. SC17764, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; then secondary antibody donkey anti-mouse IgG, FITC, Thermofischer) and LAMP2/CD107b antibody (1:200 dilution; catalog no. NBP2–22217; Novus Biologicals; then secondary antibody donkey anti-rabbit CY3) (n = 3 per group). For mitophagy in mice, we used a commercial mitophagy detection kit (catalog no. MD01–10; Dojindo Molecular Technologies) to detect mitophagy in neurons isolated from mouse tissue24; further, freshly fixed tissue was subjected to electron microscopy. Electron microscopy was used to evaluate mitophagic events in the neurons and microglia of hippocampal and PFC tissue from mice; 25–30 images were taken for neurons and microglia, independently, for each mouse sample, and data were analyzed in double-blind fashion. Mitophagy = the number of mitochondria undergoing mitophagy/total number of mitochondria per region of interest (ROI). Neuronal mitophagy in C. elegans was measured using two strains. First, we generated transgenic animals expressing a pan-neuronal mtRosella biosensor that combines a GFP variant sensitive to the acidic environment of the lysosomal lumen, fused to the pH-insensitive DsRed. Mitophagy was calculated as GFP/DsRed, thus the lower the ratio of pixel intensity, the higher the level of mitophagy. We also generated transgenic nematodes expressing the DCT-1 mitophagy receptor fused with GFP, together with the autophagosomal marker LGG-1 fused with DsRed in neurons: Ex[Prab-3DCT-1:GFP; prab-3DsRed::LGG-1]. Mitophagy was assessed using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between LGG-1 and DCT-1 colocalization. Stress-induced mitophagy was evaluated by treating the Ex[Prab-3DCT-kGFP; prab-3DsRed::LGG-1] nematodes with paraquat/para. (final concentration 8 mM). CL2241, BR5270, and other designated strains were then crossed with these mitophagy strains to monitor mitophagy levels in transgenic AD models. For all nematode experiments, NMN (5 mM) and AC (1 mM) were treated for two generations, while UA (0.1 mM) was treated from eggs for one generation. Unless specified, adult day 1 nematodes were used for the experiments. Detailed information on the in vivo mitophagy assessment in nematodes and data analysis are described elsewhere10,24. The autophagic flux, including autophagosomes and autolysosomes, was quantified using a ptfLC3 plasmid11,20.

iPSC-derived neurons.

iPSCs were differentiated into cortical neurons using protocols reported previously17,18. Briefly, iPSCs were maintained in an adherent monolayer on Matrigel-coated plates, followed by neural induction using dual SMAD inhibition (10 μ MSB431542, 1 μM dorsomorphin) in neural maintenance medium (DMEM/F-12, neurobasal/B-27/N2, 5 μg ml−1 insulin, 1 mM L-glutamine, 100 μM non-essential amino acids, 100 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1× penicillin-streptomycin). Cells were then passaged as small clusters onto coated wells (with poly-L-ornithine and laminin) after the formation of a neuroepithelial sheet. Subsequent differentiating cells formed neural rosettes in the presence of basic fibroblast growth factor. Cells were subsequently passaged and underwent final single-cell plating at day 30. We confirmed cortical identity with reverse transcription quantitative PCR and immunofluorescence microscopy. Cortical cultures were maintained in neural maintenance medium with 100 μgml−1 laminin feeding every 10 d to inhibit cell detachment.

Evaluation of p-tau in cell lines.

Three cell lines, including 2N4R-, 1N4R-, and 2N3R-overexpressed SH-SY5Y cells (generated by M. Akbari) were used to evaluate p-tau. Cells were treated with UA (50 μM) for 24 h, followed by p-tau evaluation with western blot analysis.

Mice.

All animal experiments were performed and approved by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Animal Care and Use Committee, and complied with all relevant ethical regulations. All animals were maintained at the NIA under standard conditions and fed standard animal feed. The APP/PS1 mouse strain (stock no. 004462; The Jackson Laboratory) was obtained from M. Mattson’s laboratory. APP/PS1 mice and their WT littermates were used for the experiments. APP/PS1 mice were treated with UA (200 mg kg day−1) or AC (30 mg kg day−1) by gavage starting from 6 (the age when Aβ plaques appear) to 8 months, and subsequently evaluated for behavioral and molecular end points. The 3×TgAD mouse strain was generated as described previously55. The 13-month-old 3×TgAD mice were treated with UA (200 mg kg day−1) by oral gavage for 1 month, and subsequently evaluated for behavioral and molecular end points.

MWM and Y maze.

The MWM test was performed as described previously56. The device is a circular pool (140 cm diameter) filled with water that is maintained at 22 °C. The pool was painted with non-toxic white paint. A 12-cm diameter transparent platform was placed 1 cm below the water surface at a fixed position. Mice were trained for 7 consecutive days, with 4 trials per day. Each trial lasted 60 s or until the mouse found the platform. If the mouse did not find the platform during the allotted time period, the experimenter directed the mouse to the platform. After each trial, the mouse was placed on the platform for 30 s. On the 7th day, after completing the training phase, the platform was removed for a probe trial lasting 60 s. All parameters were recorded by a video tracking system (ANY-maze, version 4.99; Stoelting). The Y maze spontaneous alternation performance (SAP) test measures the ability to recognize a previously explored environment. The maze consisted of three arms (8 × 30 × 15 cm), with an angle of 120 degrees between each arm. The number of entries and alterations were recorded by the ANY-maze video tracking system. Mice were introduced to the center of the Y maze and allowed to freely explore the maze for 10 min. Between trials the arms were cleaned with 70% ethanol solution. SAP is the subsequent entry into a novel arm over the course of 3 entries; the percentage SAP is calculated by the number of actual alternations/(total arm entries – 2) × 10057. For the APP/PS1 mice-based behavioral studies, 11–13 mice per group were used. For the 3×TgAD mice-based behavioral studies, 7 mice were used. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous studies30,39.

Object recognition and fear conditioning tests.

The object recognition tests were performed as described previously39. The device was a Plexiglas box (25 × 25 × 25 cm3). Mice could explore two identical objects for 10 min during the training phase; 1 h later, each mouse was returned to the box, which had been modified to contain one familiar object and one novel object. To exclude olfactory cues, the boxes and objects were cleaned before each test. The automatic video tracking system (ANY-maze) was used to monitor exploration behavior. Exploration time was calculated as the length of time each mouse sniffed or pointed its nose or paws at the object. The ‘recognition index’ refers to the time spent exploring the novel object relative to the time spent exploring both objects. Fear memory is measured by pairing a conditioned stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus. We used the Video Freeze Conditioning ‘Video Freeze’ software (v. 2.5.4.0; Med Associates) to measure freezing behavior. On day 1, mice were placed inside the chambers; after a 120-s baseline, a 30-s conditioned stimulus tone followed; an unconditioned stimulus foot shock was given during the last 2 s of the conditioned stimulus. This conditioned-unconditioned stimulus pairing was repeated two additional times during 180–220 s and 240–270 s. On day 2, both contextual and cued phases were carried out. During phase 1, mice were placed in the same testing chambers used on day 1 for 5 min. During phase 2, 3 h later mice were placed into modified chambers with plastic inserts; after 300 s the conditioned stimulus tone was played for 30 s at 1-min intervals (five conditioned stimulus tones in total). After 10 min, mice were returned to their housing cages. For the APP/PS1 mice-based behavioral studies, 11–13 mice per group were tested. For the 3×TgAD mice-based behavioral studies, 7 mice were tested. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications30,39.

Electron microscopy.

The ultrastructure of mitochondrial morphology was visualized and imaged with electron microscopy by a US-certified electron microscopist (J. Bernbaum). The images for neurons, astrocytes, and microglia were taken independently. Quantification of mitochondrial parameters in different cell types were performed using ImageJ (length, diameter, and area; v. 1.51j8; NIH). The percentage of damaged mitochondria as well as mitophagy-like events were calculated. All quantifications were performed in double-bind fashion.

Microarray.

Gene expression analysis was performed on hippocampal tissue from APP/PS1 and WT littermates. RNA was purified with the Nucleospin RNA isolation kit (catalog no. 740955.250; Macherey-Nagel) with initial quantitation conducted using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The quality of the RNA was inspected using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). The microarray was performed by the Gene Expression and Genomics core facility (NIA) and analyzed with DIANE 6.0, a spreadsheet-based microarray analysis program. The complete set was tested for gene set enrichment using parametric analysis of gene set enrichment. Detailed data analysis was performed as reported previously58.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence.

Briefly, anesthetized mice were perfused with 1× PBS and then 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. The collected brains were placed in 4% PFA for 24 h and then equilibrated in 30% sucrose for 24 h; 1:8 series equidistant floating 30-μm coronal sections (240 pm interval) were prepared, including the dentate gyrus area. Approximately 9–10 slices from each mouse were incubated in blocking buffer (10% donkey serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Thereafter, samples were incubated overnight with the primary antibody at 4 °C and then incubated with the appropriate fluorescent probe-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature while protected from light. Nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at a 1:5,000 dilution. Pictures were taken with an Axiovert 200M microscope (ZEISS). Specific primary antibodies used include: polyclonal rabbit anti-GFAP antibody (catalog no. Z033401–2; DAKO); mouse anti-β-Amyloid, 1–16 antibody (clone 6E10, catalog no. 803002; BioLegend); and polyclonal goat AIF-1/Iba1 Antibody (catalog no. NB100–1028; NOVUS). To evaluate Aβ plaques, tissues were stained with 6E10 antibody to recognize Aβ (1:500) and anti-GFAP antibody (1:500) to recognize astrocytes. Plaque numbers per ROI were counted and quantified. Microglia were stained with anti-IBA1 antibody, and morphological changes were assessed by measuring processes per microglial cell and average process length (μm)30. To evaluate phagocytosis, we used the number of microglia with Aβ plaques per RIO/total number of microglia per RIO. For immunofluorescence, iPSC-derived neurons were stained with designated antibodies, including: anti-MAP2 antibody (1:10,000; catalog no. ab5392; Abcam); Brn-2 antibody (1:300; catalog no. sc-6029; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-TBR1 antibody (1:1,000; catalog no. ab31940; Abcam); and anti-beta III Tubulin antibody (1:1,000; catalog no. ab18207; Abcam). This was followed by secondary antibody staining and imaging with a Leica confocal microscope.

Western blots.

Human postmortem brain tissue from AD patients and healthy controls was obtained from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center. Western blot analyses were performed as described previously11,12. Briefly, samples (for example, human iPSC-derived neurons, postmortem human hippocampal brain samples, and mouse brain samples) were collected and prepared using 1× radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (catalog no. 9806S; Cell Signaling Technology) containing protease inhibitors (catalog no. B14002; Bimake) and phosphatase inhibitors (catalog no. B15002; Bimake). Proteins were separated on an NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Protein Gel (catalog no. NP0336BOX; Thermo Fisher Scientific) or 4–15% Criterion TGX Precast Midi Protein Gel (catalog no. 5671085; Bio-Rad Laboratories) and probed with antibodies. Chemiluminescence detection was performed using a ChemiDoc XRS System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Gamma adjustment was used to reduce the dark background when necessary. Quantification was performed using ImageJ. Antibodies used were (all Cell Signaling Technology unless otherwise stated): anti-PAR polyclonal antibody (catalog no. 4336-BPC-100; Trevigen); PARP antibody (catalog no. 9542); actin antibody (catalog no. sc-1616; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Bcl-2 antibody (catalog no. sc-7382; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Mn SOD2 polyclonal antibody (catalog no. AD1-SOD-110-F; Enzo Life Sciences); AMPKα (D5A2) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 5831); phospho-AMPKα rabbit monoclonal antibody (Thr172) (catalog no. 2535); phospho-MFF (Ser146) antibody (catalog no. 49281); MFF antibody (catalog no. 86668); PINK1 antibody (catalog no. BC100–494; Novus Biologicals); parkin antibody (catalog no. 2132); phospho-TBK1/NAK (Ser172) (D52C2) XP rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 5483); TBK1/NAK (D1B4) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 3504); phospho-ULK1 (Ser555) (D1H4) (catalog no. 5869); ULK1 (D9D7) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 6439); SQSTM1/ p62 (D1Q5S) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 39749); tau (D1M9X) XP rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 46687); phospho-tau (Thr181) (D9F4G) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 12885); anti-tau (Thr231) (phospho T231) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. ab151559; Abcam); anti-tau (phospho S262) (catalog no. ab4856; Abcam; discontinued); phospho-tau (Ser202, Thr205) monoclonal antibody (catalog no. MN1020; Thermo Fisher Scientific); phospho-histone H2A.X (Ser139) (20E3) monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 9718); caspase-3 antibody (catalog no. 9662); total OXPHOS human WB antibody cocktail (catalog no. ab110411; Abcam); phospho-DRP1 (Ser616) (D9A1) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 4494); DRP1 (D6C7) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 8570); SOD1 antibody (catalog no. 2770); SOD2 (D3X8F) XP rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 13141); optineurin (D2L8S) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 58981); Bcl-rambo polyclonal antibody (catalog no. PA5–15043; Thermo Fisher Scientific); FUNDC1 polyclonal antibody (catalog no. PA5–49413; Thermo Fisher Scientific); BNIP3L/Nix (D4R4B) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 12396); beclin-1 (D40C5) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 3495); LC3 rabbit polyclonal antibody (catalog no. NB100–2220; Novus Biologicals); PSD95 (D27E11) XP rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 3450); SirT1 (1F3) mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 8469); PGC-1α (3G6) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 2178); anti-REST/NRSF rabbit polyclonal antibody (catalog no. ab21635; Abcam); Ambra1 antibody (catalog no. 24907); mouse/rat IL-10 goat polyclonal antibody (catalog no. AF519; Novus Biologicals); anti-NLRP3/ NALP3 monoclonal antibody (catalog no. AG-20B-0014-C100; Adipogen Life Sciences); caspase-1/P20/P10 (catalog no. 22915–1-AP; Proteintech); anti-CD68 mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no. ab955; Abcam); anti-IRF7 antibody (EPR4718) (catalog no. ab109255; Abcam; discontinued), CSF2RA polyclonal antibody (catalog no. PA5–37358; Thermo Fisher Scientific); anti-osteopontin rabbit polyclonal antibody (catalog no. ab8448; Abcam); synaptophysin (D35E4) rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 5461); β3-Tubulin (D71G9) XP rabbit monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 5568); and anti-E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase MUL1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (catalog no. ab84067; Abcam). All other first antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Secondary antibodies including anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; catalog no. NA931V) and anti-rabbit IgG (catalog no. NA934V) were obtained from GE Healthcare; anti-goat IgG antibody was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. A8919). Primary antibodies were used at a 1:1,000 dilution (unless otherwise stated), with secondary antibodies used at a 1:10,000 dilution (unless otherwise stated). All antibodies were validated for use in mouse/human tissues based on previous publications11,12,16,30. Detailed antibody validation profiles are available on the websites of the companies the antibodies were sourced from.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Aβ and proinflammatory/ anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Mouse hippocampal and PFC extracts were prepared as reported previously59. The accumulation of human Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 was quantified by ELISA (catalog nos. KHB3442 (Amyloid beta 42 Human ELISA Kit) and KHB3482 (Amyloid beta 40 Human ELISA Kit); Thermo Fisher Scientific). Microglia were isolated from the cortex and hippocampus of WT and APP/PS1 mice using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) method and CD11b+and CD45low cells were isolated. The antibodies used were Pacific Blue anti-mouse/human CD11b antibody (catalog no. 101224; BioLegend) and Alexa Fluor 647 anti-mouse CD45 antibody (catalog no. 103124; BioLegend). Cultured microglia were treated with Pink1 siRNA (E-004030–00-0005; Dharmacon) for 72 h and then treated with 50 μM UA for 24 h. The supernatants were analyzed by ELISA. The kits used for the cytokines were obtained from R&D Systems, including the mouse TNF-alpha (catalog no. MTA00B), IL-6 (catalog no. M6000B), and IL-10 (catalog no. M1000B) Quantikine ELISA Kits.

OCR.

We performed OCR using the Seahorse Bioscience method for both iPSC-derived neurons and C. elegans. The iPSC-derived cortical neurons were differentiated according to the aforementioned protocol in an Seahorse cell culture 96-well microplate (Agilent Technologies). The neurons were treated with UA (50 μM) for 24 h. The sensor cartridge was hydrated with Seahorse Bioscience XF96 calibrant overnight in the prep station (37 °C, w/o CO2) before running the cell culture microplate. The test assay medium was prepared by adding 2 mM L-glutamine (catalog no. 25030081; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 mM d-(+)-glucose (catalog no. G7528; Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mM sodium pyruvate (catalog no. S8636; Sigma-Aldrich) into Seahorse XF Base Medium (catalog no. 102353–100; Agilent Technologies) before washing the microplate with the preprepared assay medium according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then the culture microplate was placed in an incubator at 37 °C without CO2 for 1 h before the assay. The sensor cartridge was prepared by adding 25 μl of assay medium to port A with 2 μM oligomycin (CAS 1404–19-9, catalog no. 495455; EMD Millipore), to port B with 2 μM carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP, catalog no. C2920; Sigma-Aldrich), to port C mixed with 1 μM rotenone (catalog no. R8875; Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 μM antimycin A from Streptomyces sp. (catalog no. A8674; Sigma-Aldrich). After the run was completed, the cell microplate medium was replaced with PBS and transferred to a −80 °C freezer overnight. The protein concentration was determined using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (catalog no. 23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and was used to normalize the Seahorse XF96 primary data. The OCR of C. elegans was measured according to previous methods using a Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer (Agilent Technologies)60,61. Briefly, 200 larval stage 4 (L4) nematodes per group were transferred to designated drug plates, followed by OCR detection on adult day 3. On the day of the experiment, all the nematodes were collected, followed by washing with M9 buffer three times. Nematodes were then resuspended and transferred to 96-well standard Seahorse XF24 Cell Culture Microplates (catalog no. 100777–004; Agilent Technologies), 10–15 worms per well, and OCRs under different conditions (FCCP, sodium azide) were measured six times. After the experiments, nematodes were counted; this was followed by data normalization to the number of nematodes in each individual well. Six replicates were performed for each group and the experiment was repeated 2–3 times.

Mitochondrial parameters.

Parameters including mitochondrial ROS production and ATP levels were assessed to evaluate mitochondrial function. For mitochondrial ROS, isolated neurons were stained with MitoSOX (3 μM for 30 min) followed by fluorescence determination with a flow cytometer (BD ACCURI C6 PLUS; BD Biosciences)11,62. Flow data were analyzed with the FCS Express software (version 4; De Novo Software). ATP levels in the postmortem human brain samples and the iPSC-derived neurons were detected with a standard commercial kit (Luminescent ATP Detection Assay Kit, catalog no. ab113849; Abcam). To detect mitochondrial ROS in nematodes, they were treated with UA (0.1 mM) from L4 to adult day 3, followed by isolation of fresh mitochondria, which were then stained with a ROS dye (25 μM for 45 min; DCFDA/H2DCFDA Cellular Reactive Oxygen Species Detection Assay Kit; catalog no. ab113851; Abcam)63,64, followed by running FACS for signal quantification. We followed a standard protocol for our gating strategy65. Please see the link for an example of gating strategy for flow cytometry data (https://www.nature.com/articles/nprot.2017.133/figures/7).

Randomization and blinding.

Animal/samples (mice) were assigned randomly to the various experimental groups, and mice were randomly selected for the behavioral experiments. In data collection and analysis (for example, mouse behavioral studies, mouse imaging data analysis, as well as imaging and data analysis of electron microscopy), the performer(s) was (were) blinded to the experimental design.

Statistical analysis.

Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software) was used for the statistical analysis. Data shown are the mean ± s.e.m. with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Two-tailed unpaired t-tests were used for comparisons between two groups. Group differences were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for multiple groups. Data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our samples sizes (mouse experiments) are similar to those reported in previous publications30,39.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Legouis (Institut de Biologie Intégrative de la Cellule) for the C. elegans strain expressing GFP::LGG-2. Some of the nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health, and S. Mitani (National Bioresource Project) in Japan. We thank A. Fire for the plasmid vectors. We thank S. Cordonnier, H. Kassahun, J. Tian, W.B. Iser, M.A. Wilson, D. Figueroa, E. Fivenson, and Q.P. Lu for the experiments involving C. elegans and mice; K. Marosi and T.G. Demarest for the Seahorse studies; M. Kang, Y.Q. Zhang, E. Lehrmann, and K. Becker for the array data analysis; and A. Pasparaki for the technical support with the experiments. We thank N.F. Borhan for reading the paper. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH; the NIA (VA.B.); the Helse Sør-Øst RHF (E.F.F., grant no. 2017056 and H.N., grant no. 275911); The Research Council of Norway (E.F.F., grant nos. 262175 and 277813); Center for Healthy Aging, University of Copenhagen; the European Research Council (ERC—GA695190—MANNA, ERC—GA737599 —NeuronAgeScreen); the European Commission Framework Programmes; the Greek Ministry of Education (N.T.); and the Olav Thon Foundation (V.A.B.). K.P. is supported by an AXA Research Fund postdoctoral long-term fellowship.

Footnotes

Code availability