Cancer patients and their families often must make financial adjustments related to the costs of treatment. This articles explores the effects of financial distress on overall quality of life, focusing on the differences in results in patients treated within the different health care systems of the U.S. and France.

Keywords: Financial distress, Palliative care, Advanced cancer, Symptom distress, Quality of life

Abstract

Background.

Financial distress (FD) is common among patients with advanced cancer. Our purpose was to compare the frequency and intensity of FD and its associations with symptom distress and quality of life (QOL) in these patients in France and the U.S.

Materials and Methods.

In this secondary analysis of two cross‐sectional studies, we assessed data on 292 patients who received cancer care at a public hospital or a comprehensive cancer center in France (143 patients) or the U.S. (149 patients). Outpatients and hospitalized patients over 18 years of age with advanced lung or breast or colorectal or prostate cancer were included. Diagnosed cognitive disorder was considered a noninclusion criterion. Advanced cancer included relapse or metastasis or locally advanced cancer or at least a second‐line chemotherapy regimen. Patients self‐rated FD and assessed symptoms, psychosocial distress, and QOL on validated questionnaires.

Results.

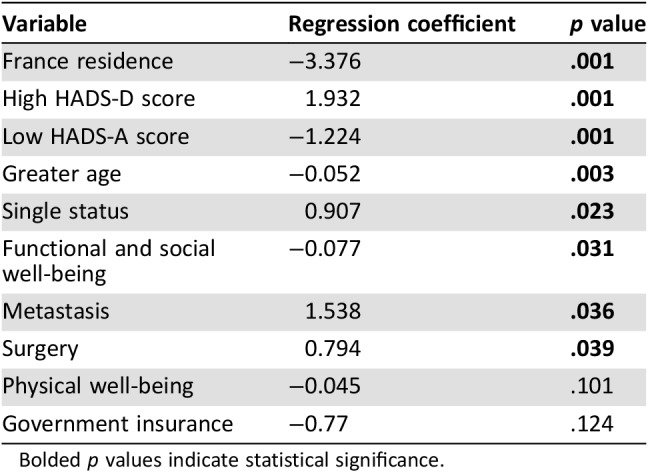

The average patient age was 59 years, and 144 (49%) were female. FD and high intensity were reported more frequently in U.S. patients than in French (respectively 129 [88%] vs. 74 [52%], p < .001; 100 [98%] vs. 48 [34%], p < .001,). QOL was rated higher by the U.S. patients than by the French (69 [SD, 18] vs. 63 [SD, 18], p = .003). French patients had more psychological symptoms such as anxiety (8 [SD, 4] vs. 6 [SD, 5], p = .008). Associations were found between FD and U.S. residence, FD and single status (0.907, p = .023), and FD and metastasis (1.538, p = .036). In contrast, negative associations were found between FD and older age (−0.052, p = .003) and FD and France residence (−3.376, p = .001).

Conclusion.

Regardless of health care system, FD is frequent in patients with advanced cancer. U.S. patients were more likely to have FD than French patients but reported better QOL. Further research should focus on factors contributing to FD and opportunities for remediation.

Implications for Practice.

Suffering is experienced in any component of the lives of patients with a life‐threatening illness. Financial distress (FD) is one of the least explored cancer‐related symptoms, and there are limited studies describing its impact on this frail population. This study highlights the high frequency and severity of FD in patients with advanced cancer in the U.S. and France as well as its impact on their physical and emotional symptoms and their quality of life in these different health care systems. It is necessary for all health care providers to explore and evaluate the presence of FD in patients living with life‐threatening illnesses.

Introduction

The impact of physical and psychological symptoms related to cancer on a patient's quality of life (QOL) is undeniable [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. The impact on personal finances and the contribution of financial distress (FD) to overall QOL are some of most important and least explored effects of cancer. Recent studies in the U.S. [6] and in France [7] showed associations between patients’ FD, QOL, and symptom distress. Kendall et al. reported that financial difficulties were a significant and frequent source of distress among patients undergoing care at a community cancer center in the U.S. [8]. In 2016, Perrone et al. [9] highlighted the association between financial difficulties and clinical outcomes in a country with a public health system.

Patients with cancer and their families frequently need to make financial adjustments in their domestic life. Extreme financial measures have been reported in the U.S. and the U.K., such as home refinancing [10], house repossessions, and even declaring bankruptcy [11]. Therefore, optimal care of patients with advanced cancer is not confined to medical and social support; it includes early and systematic analysis of the patient's socioeconomic situation.

The studies in France and the U.S. already cited [6], [7] showed that FD was frequent among both cohorts, calling into question the capacity of both health care systems to protect patients from financial concerns. The health care systems in the two countries are different. In France, the national health care system provides primary health care coverage for everyone. Private health insurance (PHI) complements or supplements public coverage [10]. Patients with cancer have 100% coverage and complete salary protection for a certain period [12]. In the U.S., the national health system covers only the portion of the population that qualifies, whether by age (Medicare) or income or social situation (Medicaid). With the 2014 health care reform in the U.S., more Americans would have received more benefit from the national health system, but PHI still provides primary health care coverage for a large portion of the population [10]. There is still limited literature regarding the impact of financial distress on the symptoms and quality of life of patients with advanced illness, especially in different health care systems.

We previously conducted studies of financial distress in each of these institutions; all patients had similar clinical characteristics, including advanced cancer, and all patients were treated by a palliative care specialist following a similar approach to assessment and management of physical and psychosocial distress. The main difference between the two cohorts was the type of health care systems where the care was provided. Therefore, we decided to compare financial distress in those patients within those health care systems.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the appropriate ethics authorities: in France, the Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud‐Est IV, and in the U.S., The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Institutional Review Board. Patients with advanced cancer receiving care at a public hospital or a comprehensive cancer center (CCC) in the U.S. and France during the period 2013–2014 were eligible. Both outpatients and hospitalized patients aged 18 years or older with advanced lung, breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer were enrolled. Advanced cancer was defined by relapse, by the presence of locally advanced disease or metastasis, or by treatment with a second‐line chemotherapy regimen. Noninclusion criteria included a cognitive disorder diagnosed by medical staff. The U.S. and French research teams used the same questionnaires. A first analysis was done separately in each country [6], [7].

Those previous studies compared two groups of patients with advanced cancer who underwent assessments using the same tools in France and the U.S. This allowed for a unique comparison of the frequency and severity of financial distress using a methodology that has not been reported before.

This article presents the results of that comparison of both U.S. and French data to highlight differences among the two patient groups and the associations of these differences with FD.

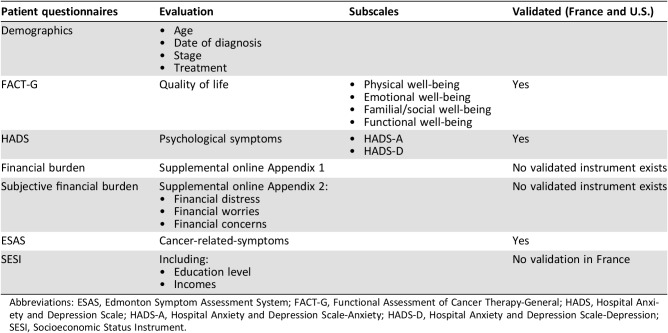

Data Collection and Survey Instruments (Table 1)

Table 1. Patient questionnaires.

Abbreviations: ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; FACT‐G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HADS‐A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale‐Anxiety; HADS‐D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale‐Depression; SESI, Socioeconomic Status Instrument.

Patient demographic and clinical information, including cancer diagnosis, cancer treatment, cancer staging, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score [13], were collected on chart report. Concerning education level and incomes, the Socioeconomic Status Instrument (SESI) was used. Except for the SESI and financial assessments scales, all instruments used in those two studies had been validated in both the U.S. and France. To collect data on cancer‐related symptoms, patients completed the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The ESAS measures the intensity of the most common cancer‐related symptoms within the last 24 hours [14], [15], [16], and the HADS is a self‐assessment tool with 14 items, with two subscales [17], [18].

Each patient's QOL score was calculated from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General (FACT‐G), a 27‐question tool validated in patients with cancer that has four subscales to assess well‐being. From these subscales, a QOL score is obtained. Both the total score and the individual scores have good internal reliability (alpha = 0.72–0,85) [19], [20].

No specific scales were validated at the time of the study to assess financial situation in medical patients. Therefore, financial burden (supplemental online Appendix 1) was assessed by questions used in previous studies of patients with cancer [21], [22]. High financial burden was defined as more than 10% of total family income spent on out‐of‐pocket expenses related to the cancer [23], [24]. FD was defined as a subjective experience of distress attributed by the patient to financial burden. Subjective financial burden was defined as the impact of FD on a patient's well‐being.

Subjective financial burden, FD, and financial concerns and worries were measured by an exploratory questionnaire (supplemental online Appendix 2). Patients were asked to score their FD on a numeric rating scale from 0 to 10, with 0 being best and 10 being worst. Patients were considered to have FD if they scored 1 or greater. High FD was defined as a score of 4 or greater.

Statistical Analysis

In descriptive analysis, quantitative variables were expressed with means and SDs, qualitative variables with absolute frequencies and percentages. The Student t test was used to compare quantitative variables and the chi‐squared test for qualitative variables. p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. We used a Bonferroni correction for all statistical analyses. A multivariate analysis by linear regression was carried out with declared FD as the dependent variable. All variables significant at p < .05 in bivariate analysis were included in the initial model. We used a stepwise descending regression, with a threshold of 0.05 for exclusion. Physical well‐being and insurance status were kept in the model as clinically important variables. Multicollinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). In the linear regression analysis, no variable had a VIF >5. Reported results were generated using SPPS software v19.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

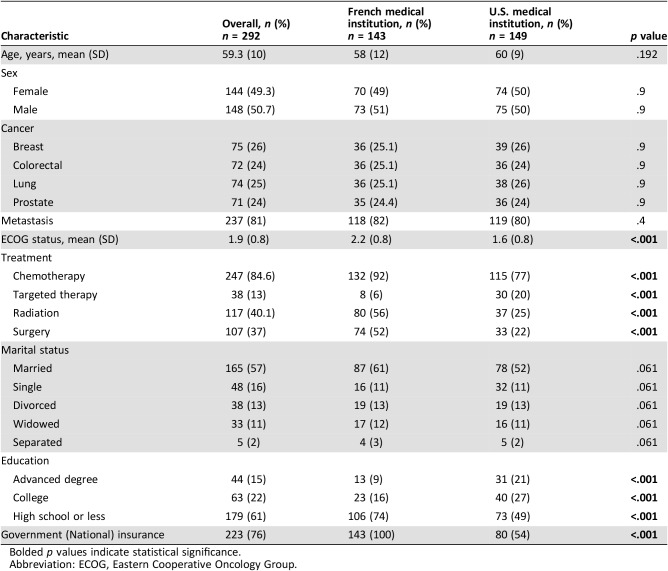

A total of 292 patients were enrolled in the study. In France, 143 patients were enrolled: 94 (66%) patients receiving care at a public hospital and 49 (34%) at a CCC. In the U.S., 149 patients were enrolled: 72 (48%) receiving care at a public hospital and 77 (52%) at a CCC. Table 2 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. The ECOG score was higher in France than in the U.S. (2.2 [SD, 0.8] vs. 1.6 [SD, 0.8], p < .001). French patients received more chemotherapy (132 [92%] vs. 115 [77%], p < .001), more radiation (80 [56%] vs. 37 [25%], p < .001), and more surgery (74 [52%] vs. 33 [22%], p < .001) than U.S. patients, whereas U.S. patients received more targeted therapy (30 [20%] vs. 8 [6%], p < .001) than French patients. There was no significant difference in sex, marital status, type of cancer, or metastatic status between the French and U.S. patients.

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants.

Bolded p values indicate statistical significance.

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

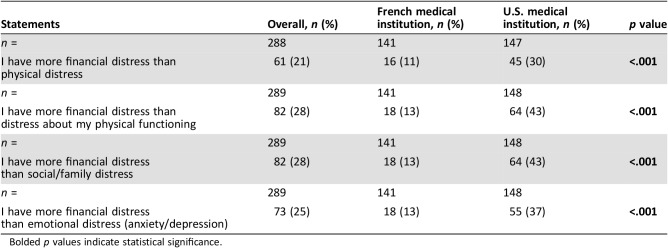

Table 3 shows differences in frequency and intensity of FD among patients from the two countries. Whereas 74 (52%) patients from France reported the presence of FD, 129 (88%) patients from the U.S. reported FD (p < .001). Whereas 48 (34%) patients in France reported severe FD, 100 (68%) in the U.S. reported severe FD (p < .001).

Table 3. Effects of financial distress on suffering.

Bolded p values indicate statistical significance.

Compared with French patients, a higher proportion of U.S. patients reported having more FD than physical distress (45 [30%] vs. 16 [11%], p < .001), more FD than distress about physical functioning (46 [31%] vs. 18 [13%], p < .001), more FD than social/familial distress (64 [43%] vs. 18 [13%], p < .001), and more FD than emotional distress (55 [37%] vs. 18 [13%], p < .001).

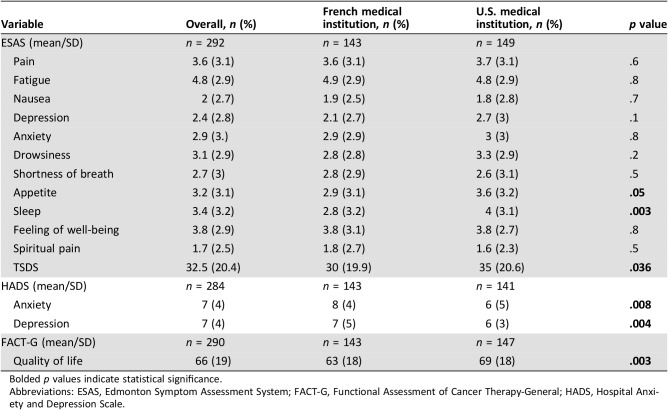

Table 4 summarizes the symptom and QOL scores of the patients in both countries. For the patients overall, the average ESAS score was 32.5 (SD, 20.4; a higher ESAS score indicates worse intensity of symptoms). The mean score for U.S. patients was higher than that for French patients (35 [SD, 20.6] vs. 30 [SD, 19.9], p = .036), but the differences on individual symptom scores were not significant except for sleep problems (4 [SD, 3.1] vs. 2.8 [SD, 3.2], p = .003). HADS‐A (anxiety) and HADS‐D (depression) scores were significantly higher in French patients than in U.S. patients (HADS‐A, 8 [SD, 4] vs. 6 [SD, 5], p = .008; HADS‐D, 7 [SD, 4] vs. 6 [SD, 3], p = .004). The average FACT‐G score was 66 (SD, 19). U.S. patients had a higher FACT‐G score than French patients (69 [SD, 18] vs. 63 [SD, 18], p = .003).

Table 4. Quality of life and cancer‐related symptoms.

Bolded p values indicate statistical significance.

Abbreviations: ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; FACT‐G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

The results of the multivariate analysis are shown in Table 5. Residence in France (p = .001) and greater age (p = .003) were associated with lower rate of declared FD. In contrast, declared FD was associated with depression (p = .001), anxiety (p = .001), single status (p = .023), the presence of metastasis (p = .036), and surgical treatment (p = .039).

Table 5. Multivariate linear regression mode.

Bolded p values indicate statistical significance.

Discussion

Our study highlights interesting differences between patients with advanced cancer in the U.S. and France. The U.S. patients were significantly more likely than the French patients to experience FD overall and to experience FD greater than physical, social/family, or emotional distress. Despite this, the U.S. patients rated their QOL more favorably than the French patients. French patients and older patients were less likely to declare FD, whereas patients with depression or anxiety, those who were single, or those who had undergone surgery or had metastatic disease were more like to report FD than their counterparts without these factors. The U.S. patients had a more favorable mean ECOG score than the French patients. The French patients were more likely to undergo standard cancer therapies such as chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery.

Our two previous studies [6], [7], separate primary analyses of the FD data for the same patients from the U.S. and France, were the first to evaluate the impact of FD on overall suffering of patients with advanced cancer and analyze the reasons for FD in the U.S. and French health care systems. The French patients’ lower rate of FD (and higher rate of cancer treatment) are not surprising considering that the costs of cancer treatment are 100% covered by the French health care system. The U.S. patients were more likely than their French counterparts to experience FD as well as severe FD; however, the French patients weren't entirely protected from FD by their national health care system. Because the direct costs of cancer treatment are covered by this system, the FD experienced by French patients is presumably linked to other financial concerns, such as loss of salary, out‐of‐pocket expenses, and indirect costs. However, further research is needed to confirm the causes of FD in French patients.

Although frequency and intensity of FD were significantly higher for the U.S. patients, the French patients had a lower level of education. This finding differs from those of other studies showing that lower education level is associated with greater financial difficulty [25], [26]. Our findings suggest that the health care system and social policy in France might cushion patients with cancer with lower educational level somewhat from FD and financial difficulty but do not protect them entirely.

Except for psychological symptoms, which were significantly more frequent in the French patients than in the U.S. patients, cancer‐related symptoms were significantly more frequent in the U.S. patients. However, the U.S. patients had a higher FACT‐G (QOL) score than the French patients, possibly because of their lower rates of psychological symptoms, their higher educational level, and their lower rates of potentially debilitating cancer treatment. FACT‐G measures emotional, social, familial, functional and physical well‐being, but there's no direct evaluation of financial well‐being. That might explain why the U.S. patients had higher QOL despite more frequent and severe declared FD. Further study should focus on financial evaluation, which needs to be systematic and early in each country.

Sharp et al. [27] reported, from an analysis of data from the National Cancer Registry Ireland, that cancer‐related financial stress and strain were consistently associated with increased risk of adverse psychological outcomes; for example, the risk of depression was three times higher in patients reporting a high degree of cancer‐related financial stress and strain.

Our research has some limitations. First, this is a secondary analysis of two cross‐sectional studies and not all the variables were obtained including the time of diagnosis of advanced cancer. Although it is important to recognize that in our study all the patients had advanced cancer, there was no significant difference in sex, marital status, type of cancer, or metastatic status; all were referred to a palliative care team by their treating oncologist, and the inception point for the assessment of symptoms of financial distress was defined as the point at which the patient was referred to a palliative care team for evaluation. This is a point in the trajectory of the illness, used by our group and others, at which the primary oncology team feels that the patient has progressive and incurable disease [28], [29]. Second is the difference between the health care settings. In France, there is no completely private establishment for comparison with U.S. private hospitals. Third was our use of the exploratory FD questionnaire, which has not been validated and thus may introduce bias. Our preliminary findings should be confirmed in large studies of patients with advanced cancer in multiple settings.

Even when the cost of cancer treatment is 100% covered, it seems to be not enough to protect patients with cancer from FD and financial difficulty. Despite the availability of the Medicare and Medicaid programs in the U.S., for example, the U.S. patients declared higher rates of FD frequency and intensity than the French patients. Complete cost coverage for cancer treatment, therefore, is not the total answer to preventing FD, but it seems to be a necessary first step. U.S. health care programs should focus on improving reimbursement policies to relieve patients’ FD. Because the cost of cancer treatment is already 100% covered by the French health care system, the French should focus on improving social policy to remove other financial concerns for patients with advanced cancer.

Conclusion

Regardless of health care system, FD is frequent in patients with advanced cancer. U.S. patients were more likely to have FD than French patients but reported better QOL.

Both countries should focus their efforts on availability and access to different resources and the assessment of financial difficulty as part of global support for patients with advanced cancer [30].

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Delgado‐Guay is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant R01CA200867.

We thank the Department of Scientific Publications at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for editorial assistance. No external funding was provided for this study.

Contributed equally

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Stuart L. Goldberg, Dhakshila Paramanathan, Raya Khoury et al. A Patient‐Reported Outcome Instrument to Assess Symptom Burden and Predict Survival in Patients with Advanced Cancer: Flipping the Paradigm to Improve Timing of Palliative and End‐of‐Life Discussions and Reduce Unwanted Health Care Costs. The Oncologist 2019;24:76–85.

Implications for Practice: A seven‐item patient‐reported outcome (PRO) instrument was administered to 1,191 patients with advanced cancers. Patients self‐reporting higher levels of physical and psychological symptom burden had inferior overall survival rates. High individual item symptom PRO responses should serve as a useful trigger to initiate supportive interventions, but when scores indicate global problems, discussions regarding end‐of‐life care might be appropriate.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Cécile Barbaret, Marvin O. Delgado‐Guay, Marilène Filbet

Provision of study material or patients: Cécile Barbaret, Marvin O. Delgado‐Guay, Christelle Brosse, Murielle Ruer, Wadih Rhondali, Léa Monsarrat, Patrick Michaud, Eduardo Bruera, Marilène Filbet

Collection and/or assembly of data: Cécile Barbaret, Marvin O. Delgado‐Guay, Christelle Brosse, Murielle Ruer, Wadih Rhondali, Léa Monsarrat

Data analysis and interpretation: Cécile Barbaret, Marvin O. Delgado‐Guay, Stéphane Sanchez, Anne Marie Schott, Eduardo Bruera, Marilène Filbet

Manuscript writing: Cécile Barbaret, Marvin O. Delgado‐Guay

Final approval of manuscript: Cécile Barbaret, Marvin O. Delgado‐Guay, Stéphane Sanchez, Christelle Brosse, Murielle Ruer, Wadih Rhondali, Léa Monsarrat, Patrick Michaud, Anne Marie Schott, Eduardo Bruera, Marilène Filbet

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Pirl WF, Temel JS, Billings A et al. Depression after diagnosis of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer and survival: A pilot study. Psychosomatics 2008;49:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L et al. Depression and survival in metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer: Effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1310–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temel JS, Greer JA, El‐Jawahri A et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado‐Guay M, Ferrer J, Rieber AG et al. Financial distress and its associations with physical and emotional symptoms and quality of life among advanced cancer patients. The Oncologist 2015;20:1092–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbaret C, Brosse C, Rhondali W et al. Financial distress in patients with advanced cancer. PLoS One 2017;12:e0176470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kendall J, Glaze K, Oakland S et al. What do 1281 distress screeners tell us about cancer patients in a community cancer center? Psychooncology 2011;20:594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perrone F, Jommi C, Di Maio M et al. The association of financial difficulties with clinical outcomes in cancer patients: Secondary analysis of 16 academic prospective clinical trials conducted in Italy. Ann Oncol 2016;27:2224–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutton PV. Health care in France and the United States. 2002. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/articles/health‐care‐in‐france‐and‐the‐united‐states‐learning‐from‐each‐other. Accessed March 8, 2019.

- 11.Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E et al. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: Results of a national study. Am J Med 2009;122:741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Les indemnités pour arrêt de travail sont‐elles imposées sur le revenu? Available at https://www.service‐public.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F3152. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- 13.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pautex S. Vers une version francophone unique de l'Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS). 2010. Available at http://www.chuv.ch/soins‐palliatifs/spl_home/spl‐recherche/spl‐recherches_en_cours.htm. Accessed August 18, 2015.

- 15.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ et al. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nekolaichuk C, Watanabe S, Beaumont C. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: A 15‐year retrospective review of validation studies (1991‐‐2006). Palliat Med 2008;22:111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravazi D, Delvaux C, Farvacques C et al. Validation de la version française du HADS dans une population de patients cancéreux hospitalisés. Rev Psychol Appliquée 1989;39:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conroy T, Mercier M, Bonneterre J et al. French version of FACT‐G: Validation and comparison with other cancer‐specific instruments. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2243–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costet N, Lapierre V, Benhamou E et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy General (FACT‐G) in French cancer patients. Qual Life Res 2005;14:1427–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markman M, Luce R. Impact of the cost of cancer treatment: An internet‐based survey. J Oncol Pract 2010;6:69–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J et al. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: The experience of patients and their caregivers. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernard DM, Banthin JS, Encinosa WE. Health care expenditure burdens among adults with diabetes in 2001. Med Care 2006;44:210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernard DSM, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out‐of‐pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2821–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.INCa (Institut national du cancer), Amalric F. Analyse économique des coûts du cancer en France. Impact sur la qualité de vie, prévention, dépistage, soins, recherche. Boulogne‐Billancourt: Institut national du cancer, 2007.

- 26.Institut de recherche et documentation en économie de la santé (France), Rochereau T, Guillaume S et al. Enquête sur la santé et la protection sociale 2010. Paris: IRDES, 2012.

- 27.Sharp L, Carsin AE, Timmons A. Associations between cancer‐related financial stress and strain and psychological well‐being among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology 2013;22:745–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yennurajalingam S, Prado B, Lu Z et al. Outcomes of embedded palliative care outpatients initial consults on timing palliative care access, symptoms, and end‐of‐life quality of care indicators among advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hui D, Mori M, Meng YC. Automatic referral to standardize palliative care access: An international Delphi survey. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: Understanding and stepping‐up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]