Financial barriers may discourage some patients with from participating in cancer clinical trials. This study sought to assess the effect of an equity intervention on the financial burden of clinical trial participants.

Keywords: Health care costs, Cancer, Financial support, Financial insolvency, Clinical trial, Health care disparities

Abstract

Background.

The financial burden experienced by patients with cancer represents a barrier to clinical trial participation, and interventions targeting patients’ financial concerns are needed. We sought to assess the impact of an equity intervention on clinical trial patients’ financial burden.

Materials and Methods.

We developed an equity intervention to reimburse nonclinical expenses related to trials (e.g., travel and lodging). From July 2015 to July 2017, we surveyed intervention and comparison patients matched by age, sex, cancer type, specific trial, and trial phase. We longitudinally assessed financial burden (e.g., trial‐related travel and lodging cost concerns, financial wellbeing [FWB] with the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity [COST] measure) at baseline, day 45, and day 90. We used longitudinal models to assess intervention effects over time.

Results.

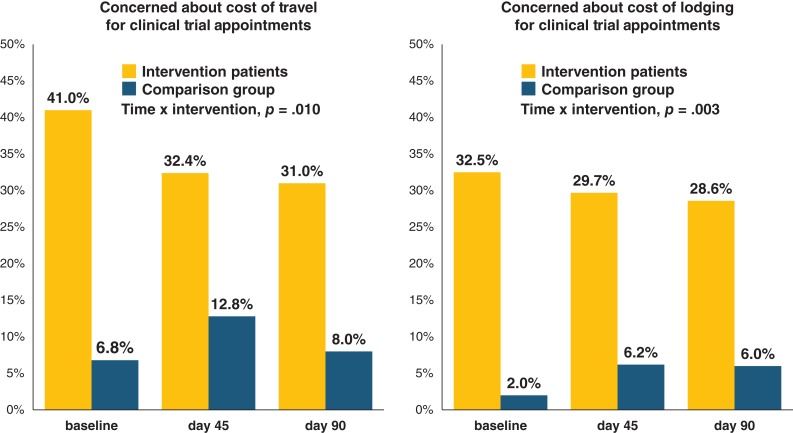

Among 260 participants, intervention patients were more likely than comparison patients to have incomes under $60,000 (52% vs. 24%, p < .001) and to report travel‐related (41.0% vs. 6.8%, p < 0.001) and lodging‐related (32.5% vs. 2.0%, p < .001) cost concerns at baseline. Intervention patients were more likely to report travel to appointments as their most significant financial concern (24.0% vs. 7.0%, p = .001), and they had worse FWB than comparison patients (COST score: 15.32 vs. 23.88, p < .001). Over time, intervention patients experienced greater improvements in their travel‐related (−10.0% vs. +1.2%, p = .010) and lodging‐related (−3.9% vs. +4.0%, p = .003) cost concerns. Improvements in patients reporting travel to appointments as their most significant financial concern and COST scores were not statistically significant.

Conclusion.

Cancer clinical trial participants may experience substantial financial issues, and this equity intervention demonstrates encouraging results for addressing these patients’ longitudinal financial burden.

Implications for Practice.

Clinical trials are critical for developing novel therapies for patients with cancer, yet financial barriers may discourage some patients from participating in cancer clinical trials. This study found that patients who received financial assistance from an equity intervention experienced significant improvements over time in their concerns about the cost of travel and lodging associated with clinical trials compared with comparison patients who did not receive financial assistance from the equity intervention. Among cancer clinical trial participants, an equity intervention shows potential for addressing patients' concerns regarding clinical trial‐related travel and lodging expenses.

Introduction

Clinical trials are vital to the development of novel therapies for patients with cancer and help advance the standard of care. However, only a small fraction of eligible patients participate in cancer clinical trials, which creates the potential for disparities in care and access to novel agents [1], [2], [3], [4]. In addition, despite the substantial resources required to open a trial, cancer clinical trials often close prematurely because of inadequate accrual, resulting in missed opportunities for growing the evidence base [5], [6], [7]. Multiple obstacles prevent patients from enrolling onto cancer clinical trials, including a lack of patient and/or provider knowledge about clinical trials, complexity of the eligibility requirements, expenses involved in participation, and difficulty with travel to trial sites [3], [8], [9], [10]. Importantly, research demonstrates that patients with limited financial resources are often underrepresented in cancer clinical trials, including older adults, uninsured patients, minority patients, and those with lower socioeconomic status [1], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. Thus, efforts to address socioeconomic disparities in cancer clinical trial participation need to focus on the financial burden associated with trial participation.

A growing body of literature has begun to recognize the financial burden experienced by patients diagnosed with cancer [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], yet little research has focused on the added financial burden of cancer clinical trial participation. Patients with cancer experience considerable out‐of‐pocket costs, resulting in significant financial distress, and studies suggest that patients with cancer are at higher risk for financial burden compared with patients with other chronic conditions [16], [18], [19]. Notably, the financial burden experienced by patients with cancer can negatively impact their clinical outcomes, including poorer quality of life, increased symptom burden, and potentially higher mortality [23], [24], [25]. Importantly, in addition to experiencing the same financial issues that all patients with cancer face, clinical trial participants must also endure the additional costs of more frequent clinical visits and travel to trial sites [18], [26], [27], [28]. Although the Affordable Care Act requires coverage of routine care costs for individuals participating in approved clinical trials [29], many patients will still have high additional out‐of‐pocket expenses related to travel to and from clinics, lodging, meals, and any extra childcare, all while absorbing the loss of income due to missed work [26]. Consequently, interventions to address the financial burden of cancer clinical trial participation are critically needed.

In prior work, we demonstrated that an equity intervention (an intervention that provides financial resources to patients) that reimburses clinical trial participants for nonclinical expenses related to trials (e.g., travel and lodging) was associated with increased clinical trial participation at our institution [30]. However, we lacked information about whether the intervention addressed patients’ financial concerns. Therefore, we conducted a prospective, longitudinal study to investigate the financial burden experienced by cancer clinical trial participants and compared outcomes between those enrolled in the equity intervention versus a matched group of comparison patients. We hypothesized that clinical trial participants enrolled in the equity intervention would report improvements in their financial concerns about the costs of travel and lodging associated with trial participation.

Materials and Methods

Equity Intervention

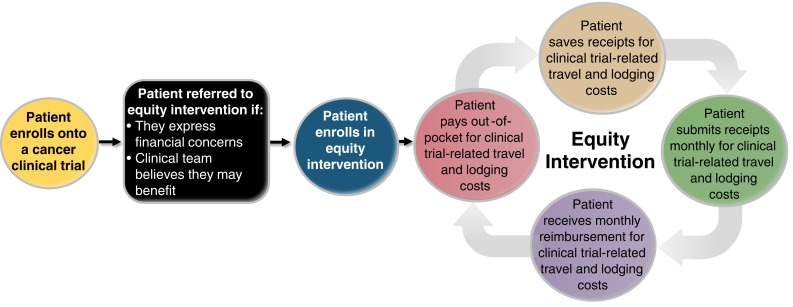

Massachusetts General Hospital partnered with the Lazarex Cancer Foundation, a 501 (c)(3) nonprofit organization, to develop an equity intervention [31]. As part of the equity intervention, patients enrolled in therapeutic cancer clinical trials could receive financial assistance for their travel and lodging expenses related to their cancer clinical trial participation (Fig. 1). We determined eligibility for assistance by taking into consideration basic information about family income, expenses, debt, and the anticipated expenses related to travel and lodging for trial visits. For patients with incomes ≤400% of the federal poverty level (FPL), the foundation reimbursed 100% of their travel and lodging expenses. For incomes between 401% and 550% of the FPL, 75% was reimbursed; for incomes between 551% and 700% of the FPL, 50% was reimbursed; and for incomes >700% of the FPL, reimbursement was considered for extenuating circumstances (e.g., excessive debt or loss of income). Once approved, patients were reimbursed monthly after they provided proof of their trial‐related travel and lodging out‐of‐pocket expenses (e.g., receipts for gasoline, tolls, parking, flights, and hotels).

Figure 1.

Equity intervention.

Participants

From July 2015 to July 2017, patients with any stage cancer in the process of being screened for a clinical trial or already participating in a therapeutic cancer clinical trial at Massachusetts General Hospital, age 18 years and older, were referred to the equity intervention by their cancer team if they expressed financial concerns. For each patient enrolled in the equity intervention, we approached a group of comparison patients matched by age, sex, cancer type, specific trial, and trial phase to ask them to participate in the study. Comparison patients did not receive financial assistance from the equity intervention.

Study Design

To examine the effects of the equity intervention on the financial burden experienced by cancer clinical trial participants, we conducted a prospective, longitudinal study to compare outcomes between those enrolled in the equity intervention and matched comparison patients. We selected this study design rather than randomization because we lack uniform screening of financial burden and patients are referred to the equity intervention by treating clinicians after the patient expresses financial concerns, and randomization would result in some of these patients not receiving needed assistance. Trained study staff obtained written, informed consent from eligible patients. Following consent, participants completed baseline study measures. The Dana‐Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Study Measures

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics.

To describe participant characteristics, we obtained information about participants’ age, sex, race, relationship status, education, insurance, clinical trial, and cancer history from the medical record. To obtain information about patient income, we asked participants to self‐report their total household income over the last year.

Financial Burden.

We longitudinally assessed patients’ financial burden at baseline, day 45, and day 90 by asking about cost concerns associated with trial‐related travel and lodging, the use of cost‐coping strategies, and financial wellbeing. We assessed patients’ cost concerns for trial‐related travel and lodging using previously validated questions about barriers to clinical trial participation [30], [32], [33]. Specifically, we asked patients their level of agreement (four‐point Likert scale) with the statement that they felt concerned about the cost of travel or lodging for clinical trial appointments, and we categorized patients based on whether or not they strongly agreed with each of these questions. Consistent with prior research, we asked patients about their use of cost‐coping strategies, such as forgoing care, taking money out of savings, selling possessions, taking on credit card debt, etc. [21], [30], [34], [35], [36]. To assess financial toxicity related to cancer and treatment, we assessed patients’ financial wellbeing using the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST) measure [37], [38]. The COST measure is an 11‐item tool, scored 0 to 44, with higher scores indicating better financial wellbeing (and lower scores indicating greater financial toxicity).

Statistical Analysis

We compared baseline patient characteristics and financial burden between intervention and comparison patients using chi‐square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. To characterize the trajectories of changes in financial burden (cost concerns associated with trial‐related travel and lodging, the use of cost‐coping strategies, and financial wellbeing) over time, we used generalized linear models with logit link function for which the model parameter estimation resorted to the generalized estimating equation to account for the within‐subject clustering of the outcomes. We investigated changes over time for the intervention group alone and also compared changes over time to the comparison group, as we expected financial burden to worsen over time in both groups, but at potentially different trajectories. Analyses estimated baseline values and rates of change separately for each outcome, and we computed an interaction term (Time × Intervention) to examine the effect of the equity intervention over time on patients’ financial burden outcomes. For all analyses, we considered two‐sided p values <.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

Participant Characteristics

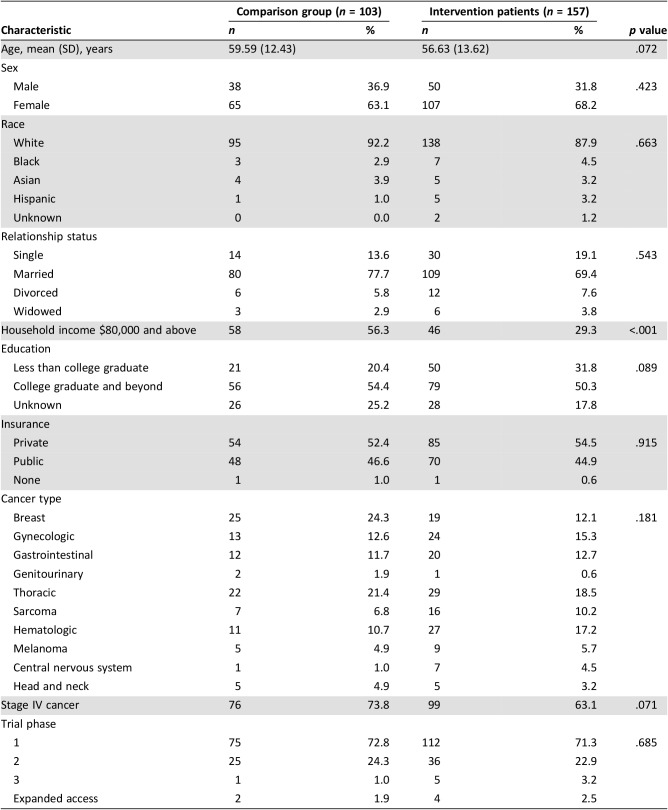

Of 345 patients approached for the study, 260 (75.4%) enrolled and completed baseline assessments (supplemental online Fig. 1). Patients were mostly white (89.6%), with a median age of 59.2 years (range: 23.8–83.3 years), and 66.2% were female. As expected, based on eligibility criteria, intervention patients were less likely than patients in the comparison group to report a household income of $80,000 and above (29.3% vs. 56.3%, p < .001; Table 1).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

On average, the program reimbursed participants from Massachusetts approximately $212 per month, regional participants (New England, excluding Massachusetts) $330 per month, and out‐of‐region participants $795 per month.

Baseline Financial Burden

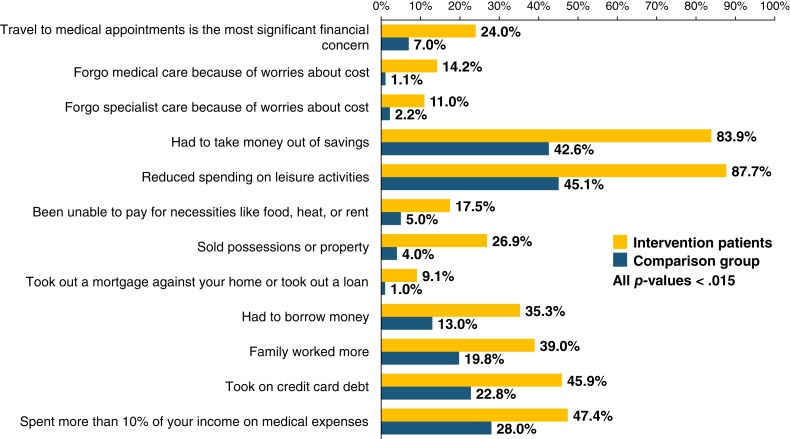

At baseline, patients enrolled in the equity intervention reported greater financial burden (Fig. 2). Specifically, intervention patients were more likely than matched comparison patients to report concerns about the cost of travel (41.0% vs. 6.8%, p < .001) and lodging (32.5% vs. 2.0%, p < .001) associated with clinical trials. Intervention patients were more likely than comparison patients to report travel to medical appointments as their most significant financial concern (24.0% vs. 7.0%, p = .001). Additionally, intervention patients were more likely to report forgoing medical care because of worries about costs (14.2% vs. 1.1%, p = .001), taking money out of savings (83.9% vs. 42.6%, p < .001), selling possessions (26.9% vs. 4.0%, p < .001), and taking on credit card debt (45.9% vs. 22.8%, p < .001; Fig. 2). Intervention patients also reported worse baseline financial wellbeing compared with comparison patients (mean COST scores: 15.32 vs. 23.88, p < .001).

Figure 2.

Baseline financial burden of intervention patients and matched comparison patients.

Intervention Effect on Patients’ Financial Burden

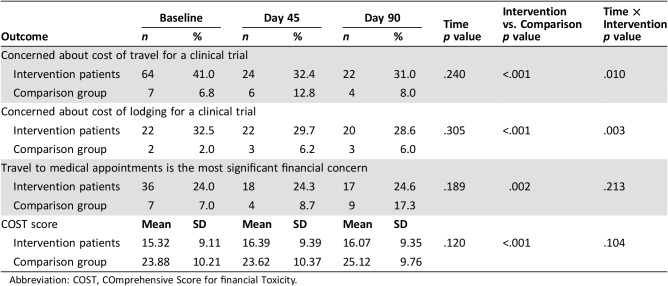

We examined intervention effects over time for the intervention group alone as well as compared with the comparison group (Table 2). Within the intervention group alone, although the proportion of patients reporting concerns about the cost of travel and lodging declined over time, changes in financial burden did not show statistical significance (supplemental online Table 1). Compared with comparison patients, those enrolled in the equity intervention experienced significant declines in their likelihood of reporting concerns about the costs of travel (Time × Intervention, p = .010) and lodging (Time × Intervention, p = .003). Specifically, from baseline to day 90, intervention patients’ financial concerns decreased, yet comparison patients’ concerns increased regarding the cost of travel (−10.0% vs. +1.2%) and lodging (−3.9% vs. +4.0%) associated with clinical trials (Fig. 3).

Table 2. Longitudinal intervention effects.

Abbreviation: COST, COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal changes in patients’ concerns about the cost of travel and lodging associated with clinical trials.

Over time, approximately one quarter of intervention patients continued to report travel to appointments as their most significant financial concern, yet the proportion of comparison patients reporting travel as their most significant financial concern rose over time (+0.6% vs. +10.3%). However, we found no significant longitudinal intervention effects for this outcome (Time × Intervention, p = .213). In addition, we found no significant intervention effects related to patients’ financial wellbeing over time (mean change in COST scores, +0.75 vs. +1.24; Time × Intervention, p = .104).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the outcomes of an equity intervention seeking to improve financial burden among cancer clinical trial participants. By design, patients who received financial assistance from the equity intervention had lower household incomes than matched comparison patients, and these individuals reported remarkably high financial burden at baseline. Despite their high baseline financial concerns, patients enrolled in the equity intervention experienced significant changes over time compared with comparison patients regarding their concerns about the cost of travel and lodging associated with clinical trials. However, patients enrolled in the intervention did not experience significant improvements in their financial wellbeing. Collectively, these data demonstrate the potential for a financial assistance program to help address financial concerns associated with cancer clinical trials, yet additional efforts are needed to comprehensively improve patients’ overall financial wellbeing.

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to investigate the effect of an equity intervention, which provides financial assistance for clinical trial‐related travel and lodging expenses, on the financial burden of cancer clinical trial participation. Although we previously demonstrated that this equity intervention was associated with increased clinical trial participation at our institution, we lacked information about whether the intervention formally addressed patients’ financial concerns [30]. Notably, this prior work highlighted the sustainability of such efforts, as the intervention patients received approximately $600 per month on average in reimbursements [31]. Importantly, our current study further underscores the feasibility of integrating a financial assistance intervention into the care of clinical trial participants and highlights the potential effects of such efforts. Additionally, this intervention is relatively low intensity, targeting only the travel and lodging expenses of cancer clinical trial participants. Therefore, given the critical need to develop and test interventions to address the financial burden of patients with cancer [39], this financial assistance intervention represents a scalable model meriting additional investigation for patients across differing geographic areas and clinical settings.

Prior studies have demonstrated that medical costs are consistently higher for patients who participate in cancer clinical trials [27], [40], and the costs of travel and lodging related to cancer clinical trials represent a barrier for trial participation [9], [10], [30]. However, research to date had not investigated whether financial assistance interventions could help to address patients’ concerns about the cost of travel and lodging associated with clinical trials. Thus, our current study investigating the impact of an equity intervention for cancer clinical trial participants represents an important first step that we hope will motivate future efforts to address these patients’ financial wellbeing.

Our study also highlights the remarkably high financial burden of cancer clinical trial patients. In our sample, most patients reported having to take money out of savings and reducing spending on leisure activities because of medical expenses. In addition, a substantial proportion reported taking on credit card debt and spending more than 10% of their income on medical expenses. These findings may have important clinical implications, as they can affect patients’ quality of life, symptom burden, treatment adherence, and potentially even survival [23], [24], [25], [41]. With such a high baseline financial burden in this sample, our findings further underscore the importance of efforts to address the financial burden experienced by cancer clinical trial patients [10], and highlight the tremendous potential for equity interventions to enhance care delivery and outcomes for these patients. Importantly, our findings also demonstrate that patients with high financial burden can successfully participate in cancer clinical trials with the help of financial assistance.

This study has several important limitations. First, we conducted this study at a single academic cancer center with limited sociodemographic diversity, which limits the generalizability of our results and prevents us from understanding the impact of the intervention among sociodemographic subgroups. Second, we lack information about factors that could influence the effect of the equity intervention, such as patients’ pre‐existing economic issues, social supports, and financial self‐efficacy. We also lack information about other known barriers to clinical trial participation (e.g., awareness and/or perceptions of clinical trials). Third, the absence of randomization introduces a multitude of issues around confounding, and the lack of a randomized controlled study design limits our ability to definitively state that the equity intervention was solely responsible for the changes in financial burden observed over time. Notably, we found baseline imbalances in household income and patient‐reported financial concerns, but this was expected, given that we sought to enroll patients in the equity intervention whose financial issues may have limited their ability to participate in cancer clinical trials. In the future, randomized controlled trials of financial assistance interventions are needed and will help definitively elucidate the efficacy of such efforts for enhancing clinical outcomes and addressing patients’ financial burden.

Conclusion

Our study describes the effects of an equity intervention on the longitudinal financial burden experienced by cancer clinical trial participants. Importantly, we found that an equity intervention has the potential to address patients’ concerns regarding clinical trial‐related travel and lodging expenses in a population with high financial burden. Notably, the financial concerns of patients enrolled in our equity intervention were substantial, placing these individuals at increased risk for poor clinical outcomes and potentially early discontinuation of trial participation. Further research efforts to investigate the efficacy of this care model to alleviate financial burden and enhance care outcomes for cancer clinical trial patients are clearly needed.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Lazarex Cancer Foundation (B.M.) and the Trefler Foundation (B.M.). This work was presented in abstract form at the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting in Chicago, IL.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Ryan D. Nipp, Hang Lee, Emily Gorton, Morgan Lichtenstein, Salome Kuchukhidze, Elyse Park, Bruce A. Chabner, Beverly Moy

Provision of study material or patients: Ryan D. Nipp, Hang Lee, Emily Gorton, Morgan Lichtenstein, Salome Kuchukhidze, Elyse Park, Bruce A. Chabner, Beverly Moy

Collection and/or assembly of data: Ryan D. Nipp, Hang Lee, Emily Gorton, Morgan Lichtenstein, Salome Kuchukhidze, Elyse Park, Bruce A. Chabner, Beverly Moy

Data analysis and interpretation: Ryan D. Nipp, Hang Lee, Emily Gorton, Morgan Lichtenstein, Salome Kuchukhidze, Elyse Park, Bruce A. Chabner, Beverly Moy

Manuscript writing: Ryan D. Nipp, Hang Lee, Emily Gorton, Morgan Lichtenstein, Salome Kuchukhidze, Elyse Park, Bruce A. Chabner, Beverly Moy

Final approval of manuscript: Ryan D. Nipp, Hang Lee, Emily Gorton, Morgan Lichtenstein, Salome Kuchukhidze, Elyse Park, Bruce A. Chabner, Beverly Moy

Disclosures

Bruce A. Chabner: PharmaMar, EMD Serono, Cyteir (C/A, H), Biomarin, Seattle Genetics, PharmaMar, Loxo, Blueprint, Bluebird, Immunomedics (OI), Eli Lilly & Co., Genentech (ET); Beverly Moy: Motus GI, Dark Canyon Laboratories (C/A [spouse]), Medscape Education (H), PUMA Biotechnology (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race‐, sex‐, and age‐based disparities. JAMA 2004;291:2720–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scoggins JF, Ramsey SD. A national cancer clinical trials system for the 21st century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nass SJ, Moses HL, Mendelsohn J, eds. A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouad MN, Lee JY, Catalano PJ et al. Enrollment of patients with lung and colorectal cancers onto clinical trials. J Oncol Pract 2013;9:e40–e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korn EL, Freidlin B, Mooney M et al. Accrual experience of National Cancer Institute Cooperative Group phase III trials activated from 2000 to 2007. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:5197–5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart DJ, Whitney SN, Kurzrock R. Equipoise lost: Ethics, costs, and the regulation of cancer clinical research. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2925–2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stensland KD, McBride RB, Latif A et al. Adult cancer clinical trials that fail to complete: An epidemic? J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young RC. Cancer clinical trials–A chronic but curable crisis. N Engl J Med 2010;363:306–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borno HT, Zhang L, Siegel A et al. At what cost to clinical trial enrollment? A retrospective study of patient travel burden in cancer clinical trials. The Oncologist 2018;23:1242–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkfield KM, Phillips JK, Joffe S et al. Addressing financial barriers to patient participation in clinical trials: ASCO Policy Statement. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:3331–3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J et al. How sociodemographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:2109–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baquet CR, Ellison GL, Mishra SI. Analysis of Maryland cancer patient participation in national cancer institute‐supported cancer treatment clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3380–3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umutyan A, Chiechi C, Beckett LA et al. Overcoming barriers to cancer clinical trial accrual: Impact of a mass media campaign. Cancer 2008;112:212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talarico L, Chen G, Pazdur R. Enrollment of elderly patients in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: A 7‐year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4626–4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL. Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3112–3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out‐of‐pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2821–2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covinsky KE, Goldman L, Cook EF et al. The impact of serious illness on patients' families. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. JAMA 1994;272:1839–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out‐of‐pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. The Oncologist 2013;18:381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stump TK, Eghan N, Egleston BL et al. Cost concerns of patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract 2013;9:251–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nipp RD, Shui AM, Perez GK et al. Patterns in health care access and affordability among cancer survivors during implementation of the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:791–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nipp RD, Zullig LL, Samsa G et al. Identifying cancer patients who alter care or lifestyle due to treatment‐related financial distress. Psychooncology 2016;25:719–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self‐reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health‐related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer 2016;122:283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker‐Seeley R et al. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1732–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lara PN Jr, Higdon R, Lim N et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: Identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1728–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldman DP, Berry SH, McCabe MS et al. Incremental treatment costs in national cancer institute‐sponsored clinical trials. JAMA 2003;289:2970–2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, Part I: A new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27:80–81, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: Opportunities in the patient protection and affordable care act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3816–3824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nipp RD, Lee H, Powell E et al. Financial burden of cancer clinical trial participation and the impact of a cancer care equity program. The Oncologist 2016;21:467–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nipp RD, Powell E, Chabner B et al. Recognizing the financial burden of cancer patients in clinical trials. The Oncologist 2015;20:572–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Supplemental Items for the CAHPS Clinician & Group Survey. 2012. Available at https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys‐guidance/item‐sets/cg/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meropol NJ, Albrecht TL, Wong YN et al. Randomized trial of a web‐based intervention to address barriers to clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(suppl 15):6500a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics . National Health Interview Survey. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm. Accessed February 16, 2019.

- 35.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality , US Department of Health and Human Services. Medical expenditure panel survey, 2009. Available at http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/. Accessed February 16, 2019.

- 36.Kuhlthau KA, Nipp RD, Shui A et al. Health insurance coverage, care accessibility and affordability for adult survivors of childhood cancer: A cross‐sectional study of a nationally representative database. J Cancer Surviv 2016;10:964–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient‐reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 2017;123:476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient‐reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer 2014;120:3245–3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zafar SY. Financial toxicity of cancer care: It's time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fireman BH, Fehrenbacher L, Gruskin EP et al. Cost of care for patients in cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zullig LL, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D et al. Financial distress, use of cost‐coping strategies, and adherence to prescription medication among patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract 2013;9(suppl 6):60s–63s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]