Abstract

Lessons Learned.

In terms of efficacy and safety, good results were obtained with S‐1 and paclitaxel (PTX) combination therapy.

The findings suggest that S‐1 and PTX combination therapy is a feasible treatment option in patients with previously treated non‐small cell lung cancer.

Background.

Although monotherapy with cytotoxic agents, including docetaxel and pemetrexed, is recommended for patients with previously treated advanced non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), its outcomes are unsatisfactory. S‐1 is an oral fluoropyrimidine agent that consists of tegafur, 5‐ chloro‐2, 4‐dihydroxypyridine, and potassium oxonate. S‐1 is approved for patients with gastric cancer in 7 Asian countries and 15 European countries. It is also approved for patients with eight type of cancers, including NSCLC, in Japan. We evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of S‐1 and paclitaxel (PTX) combination therapy in patients with previously treated NSCLC.

Methods.

Oral S‐1 was administered thrice weekly on days 1–14 at 80, 100, and 120 mg/day in patients with body surface areas of <1.25, 1.25–1.5, and >1.5 m2, respectively. PTX was administered at 80 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8. Primary endpoint was response rate, and secondary endpoints were progression‐free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and safety.

Results.

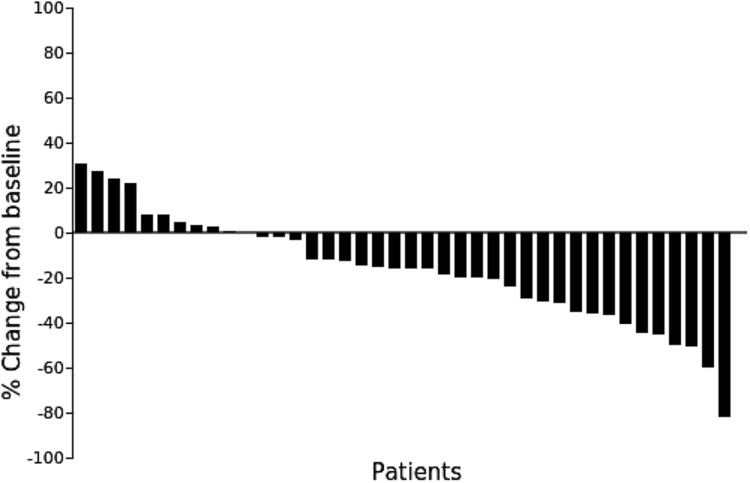

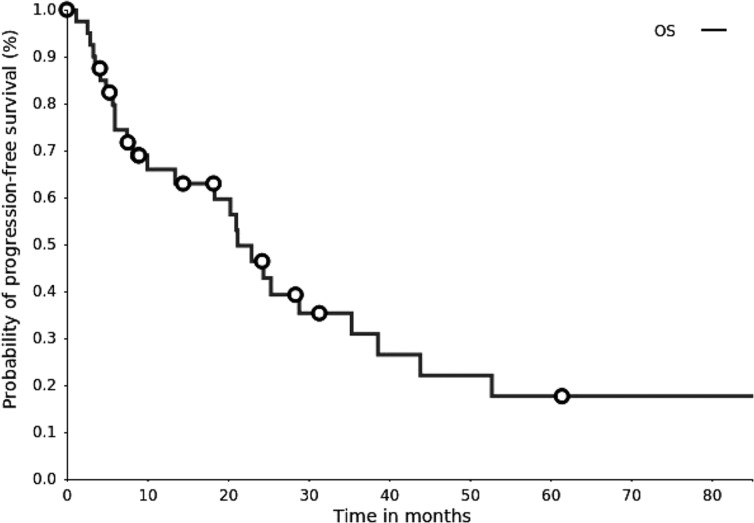

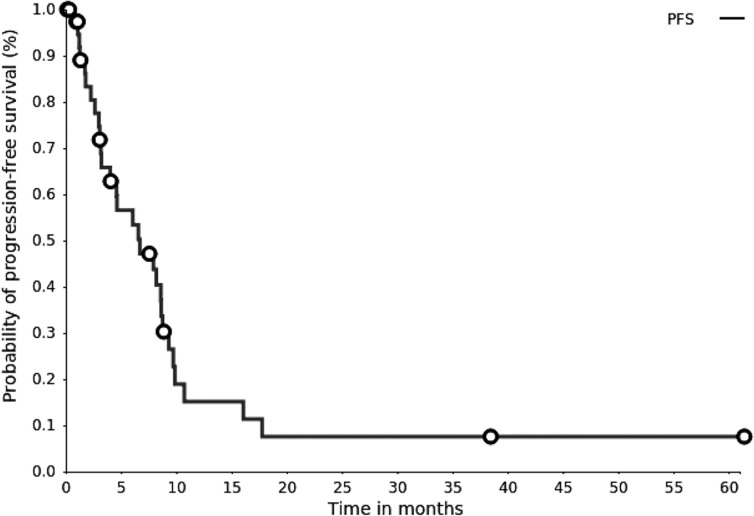

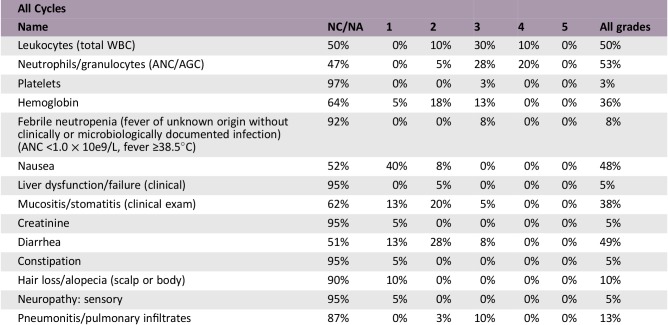

Forty patients were enrolled, with response and disease control rates of 27.5% and 75.0%, respectively (Fig. 1). Median PFS and OS were 6.5 and 20.7 months, respectively. Grade 3/4 anemia and thrombocytopenia were seen in five (12%) and one (2%) patients, respectively. Febrile neutropenia occurred in three patients (7%). Common grade 3/4 nonhematological toxicities were stomatitis (5% of patients), diarrhea (7% of patients), and interstitial lung disease (one patient). No treatment‐related deaths were observed.

Conclusion.

This S‐1 and PTX cotherapy dose and schedule showed satisfactory efficacy, with mild toxicities, in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC.

Abstract

经验总结

• 在疗效和安全性方面,S‐1 联合紫杉醇 (PTX) 治疗效果良好。

• 研究结果表明,S‐1 联合 PTX 治疗经治非小细胞肺癌是一种可行的治疗方案。

摘要

背景。虽然对于既往经治的晚期非小细胞肺癌 (NSCLC) 的治疗,建议使用多烯紫杉醇和培美曲塞等细胞毒性药物单药疗法,但其结果并不令人满意。S‐1 是一种口服氟尿嘧啶制剂,由替加氟、5‐氯‐ 2、4 ‐二羟基吡啶和氧酸钾组成。S‐1 已在 7 个亚洲国家和 15 个欧洲国家获批用于胃癌患者的治疗。而且,日本已批准 S‐1 用于包括NSCLC在内的八种癌症患者的治疗。本研究评估了 S‐1 联合紫杉醇 (PTX) 治疗既往经治 NSCLC 的疗效和毒性。

方法。对于体表面积 <1.25、1.25‐1.5 和 >1.5 m2 的患者,在第 1‐14 天口服 S‐1,每周三次,每次分别80 mg/天、100 mg/天、120 mg/天。在第 1 天和第 8 天按照PTX 80 mg/m2 的剂量给药。主要终点为缓解率,次要终点为无进展生存期 (PFS)、总生存期 (OS) 和安全性。

结果。共入组 40 例患者,缓解率为 27.5%,疾病控制率为 75.0%(图 1)。中位PFS 和 OS 分别为 6.5 个月和 20.7 个月。5 例 (12%) 患者出现 3/4 级贫血,1 例 (2%) 出现血小板减少。3 例 (7%) 患者出现发热性中性粒细胞减少症。常见 3/4 级非血液学毒性为口炎 (5%)、腹泻 (7%) 和肺间质病变 (1 例)。未出现与治疗相关的死亡事件。

结论。对于既往经治的晚期 NSCLC 患者,以文中所述剂量和用药时间安排给予 S‐1 与 PTX 联合治疗疗效显著,不过会引起轻微的毒性反应。

Discussion

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths in the world. NSCLC accounts for approximately 85% of lung cancer cases. Treatment for advanced NSCLC is dramatically evolving owing to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and molecular target drugs. Currently, ICIs are recommended in the standard initial treatments of advanced or recurrent lung cancer without driver oncogene mutations, as single agents and ICI‐platinum based combination chemotherapy [1], [2], [3]. When ICIs are used for primary treatment, cytotoxic anticancer drugs are options for second‐line treatment during recurrence. The role of cytotoxic anticancer drugs is still important. Docetaxel (DOC) and pemetrexed (PEM) are used as single agents in previously treated cases; combination treatment with ramucirumab is recommended for younger patients with good performance status (PS). However, this antiangiogenic agent is not suitable for some patients; the incidence of adverse events is sometimes higher with combination therapy [4]. Single‐agent DOC or PEM therapy is an option when angiogenesis inhibitors are unavailable, but the response rates for single‐agent therapy are low [5], [6]; therefore, new safe and effective therapies are much needed.

Figure 1.

The ORR and disease control rates were 27.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 14.6‐43.9) and 75.0% (95% CI, 58.8‐87.3), respectively.

Although nonplatinum combinations provide an alternative strategy, several randomized trials comparing single‐agent with doublet chemotherapy had insufficient power to detect potentially relevant differences in survival [7], [8].

We had previously conducted a phase I/II study of S‐1 and paclitaxel (PTX) combination therapy in previously untreated non‐small cell lung cancers among the elderly (≥70 years of age). In the phase II study at the recommended dose (RD; S‐1, 80 mg/m2; PTX, 80 mg/m2), the response and disease control rates were 53.3% and 93.3%, respectively, and the toxicities were mild [9], [10]. The present phase II study evaluated the efficacy and safety of S‐1 and PTX combination therapy after second‐line treatment in patients with previously treated NSCLC. These results warrant further evaluation of this combination in phase III trials.

Trial Information

- Disease

Lung cancer – NSCLC

- Stage of Disease/Treatment

Metastatic/advanced

- Prior Therapy

1 prior regimen

- Type of Study – 1

Phase II

- Type of Study – 2

Single arm

- Primary Endpoint

Overall response rate

- Secondary Endpoint

Progression‐free survival

- Secondary Endpoint

Overall survival

- Secondary Endpoint

Safety

- Additional Details of Endpoints or Study Design

- Patient eligibility: The patient eligibility criteria were as follows: (a) presence of at least one measurable tumor lesion; (b) cytologically or histologically confirmed NSCLC; (c) presence of confirmed stage IIIB disease without any indications for radiotherapy or stage IV disease in patients who failed at least one prior line of chemotherapy, including platinum‐based regimens; (d) more than 4 weeks since the last administration of prior chemotherapy; (e) age ≥20 years; (f) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS of 0 or 1; (g) adequate organ function and bone marrow activity (neutrophil count ≥3,000/μL, platelet count ≥100,000/μL, and hemoglobin level ≥9.5 g/dL), serum bilirubin concentration ≤1.5 mg/dL, serum aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase concentrations less than or equal to twice the upper limit of the normal range, creatinine level less than or equal to upper limit of normal, and creatinine clearance rate ≥60 mL/minute; (h) life expectancy >2 months; and (i) able to take medications orally. All patients had to provide written informed consent. The patient exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) presence of interstitial pneumonia; (b) severe concomitant disease (e.g., severe cardiac disease, uncontrolled diabetes, or severe infection); (c) active concomitant malignancy; (d) severe hypersensitivity to either the study drugs or alcohol; and (e) receiving treatment with flucytosine.

- Treatment plan: The RD of PTX, that is, 80 mg/m2, from the results of our phase I study was used. In each 21‐day cycle, 80 mg/m2 of PTX was administered on days 1 and 8. S‐1 was administered twice daily from days 1 to 14. The dose of S‐1 was calculated according to the patient's body surface area as follows: 40, 50, and 60 mg S‐1 for body surface areas of <1.25, 1.25–1.50, and ≥1.50 m2, respectively. Treatment was continued until disease progression, appearance of unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal of consent by the patient, and termination of treatment by the attending physician. The criteria for initiation of treatment were as follows: white blood cell (WBC) count ≥3,000/mm3; neutrophil count ≥1,500 cells/mm3; platelet count ≥75,000/mm3; creatinine level less than or equal to upper limit of normal; and peripheral neuropathy or other nonhematological toxicities of grade 1 or lower, excluding pigmentation and alopecia. Criteria for discontinuation of PTX on day 8 and S‐1 included WBC count ≥2,000/mm3; neutrophil count ≥1,000 cells/mm3; platelet count ≥75,000/mm3; creatinine level less than or equal to upper limit of normal; and peripheral neuropathy or other nonhematological toxicities of grade 1 or lower, excluding pigmentation and alopecia. The administration of S‐1 and PTX was delayed until the criteria were satisfied up to a maximum of 14 days. Criteria for the reduction of the dose of S‐1 and PTX in the next cycle were WBC count <1,000/mm3; neutrophil count <500/mm3; platelet count <25,000/mm3; or occurrence of peripheral neuropathy or toxicities, excluding pigmentation and alopecia of grade 3 or higher, during the previous cycle. S‐1 dose was reduced from 120 to 100 mg/day, 100 to 80 mg/day, or 80 to 50 mg/day, whereas PTX dose was reduced by 10 mg/m2.

- Evaluation: After the treatment was started as per protocol, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging were performed monthly to evaluate the anticancer efficacy of the combination treatment; physical examination and laboratory tests for evaluation of hepatic or renal function and complete blood counts were performed at least once a month. Responses were graded as complete response, partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD) according to RECIST. Toxicity was assessed using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0.

- Statistical analysis: The primary endpoint of this study was overall response rate (ORR), and the secondary endpoints were PFS, OS, and safety. The sample size was calculated with α and β errors of 0.05 and 0.1, respectively. The threshold and estimated ORRs were 5% and 20%, respectively. The estimated minimum sample size was 38. Considering patient ineligibility, we needed at least 40 patients. OS and PFS were calculated using the Kaplan‐Meier method. All analyses were performed using JMP software program version 8.0 for Windows.

- Ethics: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan (RBMR‐C‐974). The trial was supervised and managed by the Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

- Investigator's Analysis

Active and should be pursued further

Drug Information

- Drug 1

- Generic/Working Name

S‐1

- Company Name

Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

- Dose

40, 50, and 60 mg/m2

- Route

p.o.

- Schedule of Administration

S‐1 was administered twice daily from days 1 to 14. The dose of S‐1 was calculated according to the patient's body surface area as follows: 40, 50, and 60 mg S‐1 for body surface areas of <1.25, 1.25–1.50, and ≥1.50 m2, respectively.

- Drug 2

- Generic/Working Name

Paclitaxel

- Company Name

Bristol‐Myers Squibb

- Dose

PTX was fixed as 80 mg/m2

- Route

IV

- Schedule of Administration

The RD of PTX, that is, 80 mg/m2, from the results of our phase I study was used. In each 21‐day cycle, 80 mg/m2 of PTX was administered on days 1 and 8.

Patient Characteristics

- Number of Patients, Male

28

- Number of Patients, Female

12

- Stage

Presence of confirmed stage IIIB disease without any indications for radiotherapy or stage IV disease in patients who have experienced disease progression on at least one prior line of chemotherapy, including platinum‐based regimens

- Age

Median (range): 65 (35–83) years

- Performance Status: ECOG

-

0 — 14

1 — 21

2 — 5

3 —

Unknown —

- Cancer Types or Histologic Subtypes

Adenocarcinoma, 23; squamous cell carcinoma, 15; non‐small cell lung carcinoma, 2.

Primary Assessment Method

- Title

ORR

- Number of Patients Screened

40

- Number of Patients Enrolled

40

- Number of Patients Evaluable for Toxicity

40

- Number of Patients Evaluated for Efficacy

40

- Evaluation Method

RECIST 1.1

- Response Assessment CR

n = 0 (0%)

- Response Assessment PR

n = 11 (27.5%)

- Response Assessment SD

n = 19 (47.5%)

- Response Assessment PD

n = 10 (25%)

- Response Assessment OTHER

n = 0 (0%)

- (Median) Duration Assessments PFS

6.5 months, CI: 3.2–8.5

- (Median) Duration Assessments OS

20.7 months, CI: 8.1–25.0

Secondary Assessment Method

- Title

OS

- Number of Patients Screened

40

- Number of Patients Enrolled

40

- Number of Patients Evaluable for Toxicity

40

- Number of Patients Evaluated for Efficacy

40

- (Median) Duration Assessments OS

20.7, CI: 8.1

Kaplan‐Meier plot. Overall survival (OS). The median survival time was 20.7 months (95% confidence interval, 8.1–25.0 months).

- Title

PFS

- Number of Patients Screened

40

- Number of Patients Enrolled

40

- Number of Patients Evaluable for Toxicity

40

- Number of Patients Evaluated for Efficacy

40

- Evaluation Method

RECIST 1.1

- (Median) Duration Assessments PFS

6.5, CI: 3.2

Kaplan‐Meier plot. Progression‐free survival (PFS). The median PFS survival was 6.5 months (95% confidence interval, 3.2–8.5 months).

Adverse Events

- Adverse Events Legend

- The median number of completed cycles was 3 (range 1–10). All patients were assessed for toxicity. Grade 3/4 anemia and thrombocytopenia was seen in five (12%) and one (2%) patients, respectively. Febrile neutropenia was seen in three patients (7% of patients). The most common grade 3/4 nonhematological toxicities were stomatitis (5% of patients), diarrhea (7% of patients), and grade 3 interstitial lung disease (one patient). No treatment‐related deaths were observed.

- Abbreviations: AGC, absolute granulocyte count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; NC/NA, no change from baseline/no adverse event; WBC, white blood cell.

Assessment, Analysis, and Discussion

- Completion

Study completed

- Investigator's Assessment

Active and should be pursued further

Monotherapy with docetaxel (DOC) or pemetrexed (PEM) is recommended for the treatment of previously treated advanced non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases. The results of the REVEL study demonstrated significantly prolonged progression‐free survival (PFS) with ramucirumab (RAM) compared with DOC alone [4]. A combination of DOC + RAM is currently recommended for treating younger patients with good performance status. However, RAM is often unsuitable for many patients, including those with hemoptysis, tumor vascular invasion, and postradiation therapy; adverse events such as neutropenia and febrile neutropenia (FN) may be difficult to manage. In cases unsuited for RAM therapy, single‐agent cytotoxic drugs are recommended. Controlled trials with DOC versus PEM [6] and DOC versus S‐1 [11] have been conducted to date, but none of the trials showed superiority, with response rates of around 8.3%–9.9%. Currently, there is no treatment that provides superior results to those of single‐agent DOC. A meta‐analysis of nonplatinum doublets reported that although the overall response rate (ORR) and PFS tended to be superior, overall survival (OS) was not improved; these doublets also demonstrated a higher incidence of adverse events [12].

In the present study combining S‐1 with paclitaxel, the ORR was 27. 5%, and the primary endpoint was met. This was more favorable than the response rates of single‐agent DOC or single‐agent S‐1, with confirmed noninferiority to single‐agent DOC [11]. The results also surpassed the response rate of DOC + RAM (23%) reported in the REVEL study. The study combination demonstrated a PFS of 6.5 months, which was better than the 4.5 months demonstrated by DOC + RAM. The OS was found to be 20.7 months, which possibly surpassed the results of the meta‐analysis [12].

In addition, this study found similar response rates in both nonsquamous and squamous cell carcinomas and may be effective in either histology. Angiogenesis inhibitors cannot be used in certain squamous cell carcinoma cases; squamous cell carcinomas had made up only 25% of the population in the REVEL study. We speculate that this study combination could be an effective treatment option, particularly for patients with previously treated squamous cell carcinomas.

In terms of safety, neutropenia above grade 3/4 was the most common with this combination, at 47.5%. In comparison, grade 3/4 neutropenia was reported in 49% of patients receiving DOC + RAM. FN was noted in 7% of this study cohort. This was less than that reported in the REVEL study (16%). The incidence of FN in the meta‐analysis of nonplatinum combination therapy was 7%, which was similar to our findings. Among nonhematologic toxicities, stomatitis and diarrhea tended to be more common compared with the results of other concomitant treatments. This could have been due to S‐1, but the incidence was higher than that reported with S‐1 alone [13] and with DOC + S‐1 combination therapy [14]. Conversely, in a report of a phase II study of S‐1 + PTX in gastric cancer, stomatitis of grade 3 or higher was reported in 28% [15]; caution should be exercised in interpreting these results as these mucosal lesions may have been increased owing to PTX. In this study, anticancer therapy could be continued with supportive treatment and was considered well tolerated. Also, when compared with our previous phase II study in older adults with similar tumors, neutropenia (47.5% vs. 52. 9%), FN (7% vs. 11. 8%), and stomatitis (5% vs. 23. 5%) were all lower in this study. These results demonstrate that this schedule and dose tailored for older adults was better tolerated by adults of all ages in this cohort, with similar efficacy. As a supplement, S‐1 is labelled for use in many European countries, and for head and neck cancer, colorectal cancer, and non‐small cell lung, breast, pancreatic, and biliary tract cancers in several countries in Asia [16]. It has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [16].

In conclusion, the results of this study met the criteria for the primary endpoint. Combination chemotherapy with S‐1 and PTX was found to be effective and well tolerated in patients with previously treated NSCLC. These results warrant further evaluation of this combination in phase III trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Contributed equally.

Footnotes

UMIN Clinical Trials Identifier: UMIN000035812

Sponsor: Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine

Principal Investigator: Yoshinobu Iwasaki

IRB Approved: Yes

Disclosures

Junji Uchino: Eli Lilly Japan K.K. (RF); Koichi Takayama: Chugai‐Roche Co. and Ono Pharmaceutical Co. (RF), AstraZeneca, Chugai‐Roche Co., MSD‐Merck Co., Eli Lilly Co., Boehringer‐Ingelheim Co., Daiichi‐Sankyo Co. (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Reck M, Rodríguez‐Abreu D, Robinson AG et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD‐L1‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi L, Rodríguez‐Abreu D, Gadgeel S et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2078–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F et al. Atezolizumab for first‐line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2288–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garon EB, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second‐line treatment of stage IV non‐small‐cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum‐based therapy (REVEL): A multicentre, double‐blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2014;384:665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN et al. Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum‐containing chemotherapy regimens. The TAX 320 Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2354–2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1589–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeda K, Negoro S, Tamura T et al. Phase III trial of docetaxel plus gemcitabine versus docetaxel in second‐line treatment for non‐small‐cell lung cancer: Results of a Japan Clinical Oncology Group trial (JCOG0104). Ann Oncol 2009;20:835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gebbia V, Gridelli C, Verusio C et al. Weekly docetaxel vs. docetaxel‐based combination chemotherapy as second‐line treatment of advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients. The DISTAL‐2 randomized trial. Lung Cancer 2009;63:251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chihara Y, Date K, Takemura Y et al. Phase I study of S‐1 plus paclitaxel combination therapy as a first‐line treatment in elderly patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Invest New Drugs 2019;37:291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshimura A, Chihara Y, Date K et al. A phase II study of S‐1 and paclitaxel combination therapy as a first‐line treatment in elderly patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. The Oncologist 2019;24:459‐e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nokihara H, Lu S, Mok TSK et al. Randomized controlled trial of S‐1 versus docetaxel in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum‐based chemotherapy (East Asia S‐1 Trial in Lung Cancer). Ann Oncol 2017;28:2698–2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Maio M, Chiodini P, Georgoulias V et al. Meta‐analysis of single‐agent chemotherapy compared with combination chemotherapy as second‐line treatment of advanced non–small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1836–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawahara M, Furuse K, Segawa Y et al. Phase II study of S‐1, a novel oral fluorouracil, in advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2001;85:939–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komiyama K, Kobayashi K, Minezaki S et al. Phase I/II trial of a biweekly combination of S‐1 plus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non‐small cell lung cancer (KRSG‐0601). Br J Cancer 2012;107:1474–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mochiki E, Ohno T, Kamiyama Y et al. Phase I/II study of S‐1 combined with paclitaxel in patients with unresectable and/or recurrent advanced gastric cancer. Br J Cancer 2006;95:1642–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA. DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]