Why was the cohort established?

The ASPREE Longitudinal Study of Older Persons (ALSOP) is a longitudinal cohort study of ageing which involves approximately 90% of the Australian participants in the ASPREE clinical trial (see below). The aim of ALSOP is to examine a broad range of general health, lifestyle, behavioural, social, economic and environmental factors that are relevant to the ageing Australian population, and to link these to future health status. The ultimate goal is to identify new strategies to maintain the health of ageing Australians and allow maintenance of independent living.

The rationale for the establishment of ALSOP is the need to understand and address medical and social issues arising from the rapid increase in the numbers of Australians expected to survive into their 70 s, 80s and 90 s in future years. This is the result of both a decline in the death rate of middle-aged Australians and a substantial decrease in mortality among the elderly.1 However, ageing is commonly accompanied by an array of chronic disabling diseases and disabilities leading to both a reduced quality of life and substantial costs for the community.

An essential prerequisite for healthy ageing is the prevention and/or the effective management of these diseases. Foremost amongst these are dementia, musculoskeletal disorders, cardiovascular disease, cancer, depression and vision and hearing disorders. Observational cohort studies have been fundamental in identifying risk factors and prevention opportunities for various diseases, commonly suggesting hypotheses for subsequent testing in clinical trials. Observational studies also play an important role in measuring and predicting health service requirements and targeting health expenditure to areas of most need.

The need for a major longitudinal study of ageing to identify preventive opportunities among elderly Australians has been recognized and strongly endorsed.2 However, such study proposals typically require a significant commitment for long-term funding, which has been difficult to achieve in the current research funding environment. Building a cohort study within a clinical trial has provided the opportunity to undertake ALSOP at a marginal cost.

Although there have been other cohort studies focusing on older Australians (Table 1), ALSOP has certain unique features in its size, contemporariness, and the depth of information obtained from each participant. The ASPREE trial population was suited for inclusion in a community-based cohort study of the elderly because the participants are typical of a substantial proportion of the elderly Australian population. Rather than resembling a random population sample (which would have included a percentage with life-limiting illness) the ALSOP population most closely reflects the elderly Australia population that has reached age 70 or beyond in relatively good health. At present, approximately 80% of Australian males and 90% of females survive to 70 years and beyond, after which time deteriorating health and increasing health expenditure are the norm.3

Table 1.

Comparative scope of Australian-based longitudinal studies of healthy ageing

| Australian longitudinal studies in elderly populations | Men and women included | Cognition assessed | >5 follow- up surveys | Year established | Rural and metropolitan representation | Age at study entry | Number of participants | Recruited from >1 Australian state |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASPREE Longitudinal Study of Older Persons (ALSOP) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2012 | ✓ | ≥70 y | 14 892 | ✓ |

| Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (1921–26 birth cohort)13 | ✓ | 1996 | ✓ | 70–75 y | 12 432 | ✓ | ||

| 45 and Up Study14 | ✓ | 2005 | ✓ | ≥45 y (≥70y+) | 266 848 (72 346) | |||

| Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ALSA)15 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1992 | ✓ | ≥65 y | 2087 | |

| Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Flagship Study of Ageing (AIBL)16 | ✓ | ✓ | 2006 | ≥60 y | 1112 | ✓ | ||

| Older Australian Twin Study (OATS)17 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2006 | ≥65 y | 623 | ✓ | |

| Sydney Memory and Ageing Study (MAS)18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2005 | 70–90 y | 1037 | ||

| Melbourne Longitudinal Studies on Healthy Ageing Program (MELSHA)19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1994 | ≥65 y | 1000 | ||

| Dubbo Study20 | ✓ | 1988 | ≥60 y | 2805 | ||||

| Health in Men Study (HIMS)21 | ✓ | 1996 | 65–83 y | 12 203 | ||||

| Busselton Health Ageing Study (BHAS)22 | ✓ | 2010 | 45–69 y | 5107 | ||||

| Blue Mountains Eye Study (BMES)23 | ✓ | ✓ | 1992 | 49–97 y | 3654 | |||

| Canberra Longitudinal Study24 | ✓ | ✓ | 1990 | ≥70 y | 1045 | |||

| Personality and Total Health Through Life (60–64)25 | ✓ | ✓ | 2001 | 60–64 y | 2551 | |||

| Longitudinal Study of Ageing in Women26 | ✓ | ✓ | 2000 | 40–79 y | 511 | |||

| Sydney Older Persons’ Study27 | ✓ | ✓ | 1991 | ≥75 y | 647 | |||

| Hunter Community Study28 | ✓ | 2004 | 55–85 y | 3207 | ||||

| Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project (CHAMP)29 | 2005 | ≥70 y | 1075 |

Similarly, the active component of the placebo-controlled randomized intervention applied to 50% of the cohort is unlikely to significantly affect the cohort findings. This intervention comprised enteric-coated low-dose (100 mg) aspirin, an over-the-counter product currently used by approximately 30% of the Australian population.

Recent reviews from both Australia and the USA have identified key gaps in ageing research.4 In particular they have identified the need for multidisciplinary studies involving basic sciences, genomics and epigenetics coupled with clinical, public health and social sciences, to help understand the determinants of healthy and productive ageing. ALSOP will provide a unique platform to facilitate such research.

Who is in the ALSOP cohort?

The ALSOP cohort is drawn from Australian participants in the ASPREE clinical trial. ASPREE was a randomized study of low-dose aspirin used for primary prevention, funded primarily by the US National Institutes of Health.5 Between 2010 and 2014, ASPREE enrolled more than 19 000 initially healthy, independently living Australians and Americans aged 70 years and above or 65 years and above, who were initially free of cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment or major disability. Exclusion criteria for ASPREE were known cardiovascular disease or atrial fibrillation, dementia or score of <78 on the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination,6 disability as defined by severe difficulty or inability to perform any of the six Katz activities of daily living,7 a condition with a high current or recurrent risk of bleeding, anaemia, current use of aspirin, other antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication, uncontrolled hypertension or a condition likely to cause death within 5 years. ASPREE participants were subsequently randomized to receive either 100 mg enteric-coated aspirin or a matching placebo daily, and have currently been followed for an average 4.5 years; 16 703 of the ASPREE participants were Australians, recruited primarily with the collaboration of primary care practitioners.8 Australian ASPREE participants were invited to participate in the ALSOP substudy, which received separate ethical approval.

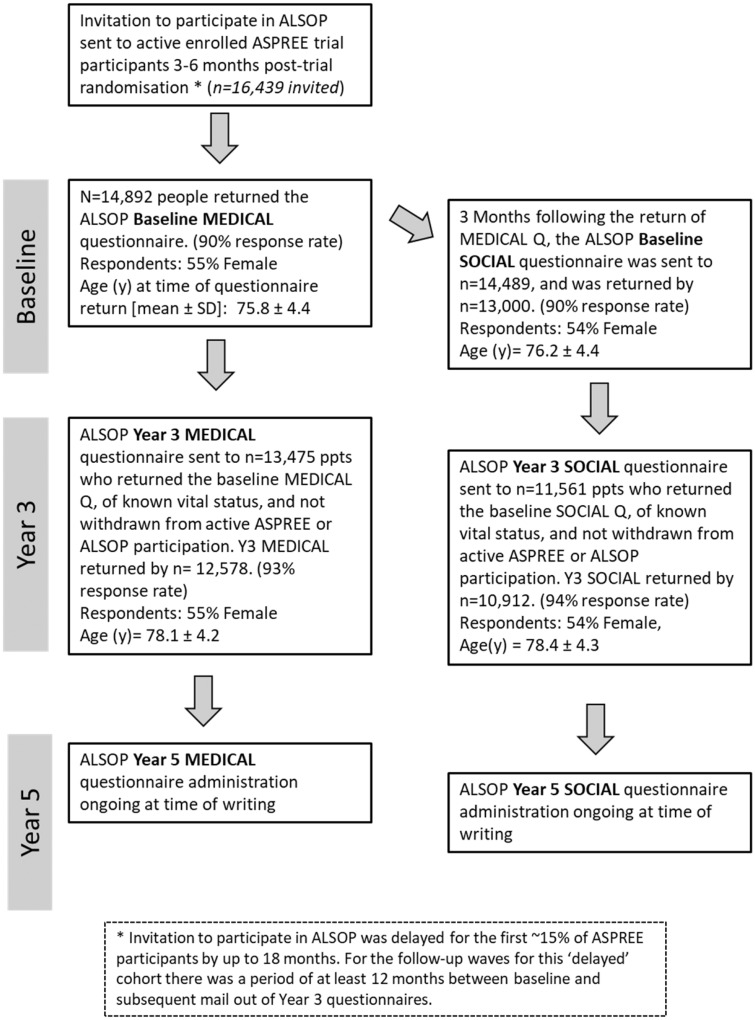

A total of 14,892 Australian ASPREE participants (89% of those eligible) agreed to participate in ALSOP, which involved completion of a set of medical and social questionnaires, mostly during the first year following enrolment into the ASPREE trial. The ALSOP consort diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the study implementation. ASPREE commenced randomization in 2010, and ALSOP commenced in early 2012. Thus for the earliest enrolled ASPREE participants (<15% of the total ALSOP cohort) there was delay of up to 15 months in the administration of the first ALSOP questionnaire. Table 2 describes the characteristics of the ALSOP cohort, the Australian ASPREE cohort from which they were recruited and the reference Australian population.

Figure 1.

ALSOP Consort diagram.

Table 2.

ALSOP cohort baseline characteristics

| ALSOP cohort (n = 14 892) | Australian ASPREE partipants (n = 16 703) | Reference Australian population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female n, (%) | 8140 (55%) | 9180 (55%) | 55.0% |

| Age | a | ||

| 70–74 y | 8675 (58%) | 9668 (58%) | 35.1% |

| 75–84 y | 5665 (38%) | 6395 (38%) | 44.8% |

| 85+ y | 552 (4%) | 640 (4%) | 20.1% |

| Area of residence | a | ||

| Metropolitan | 7804 (52.5%) | 8730 (52.3%) | 67.1% |

| Inner regional | 5327 (35.8%) | 5984 (35.8%) | 22.9% |

| Outer regional | 1727 (11.6%) | 1951 (11.7%) | 9.1% |

| Remote | 3 (0%) | 3 (0%) | 0.9% |

| Years of education | a | ||

| ≤12 y (school education) | 9021 (60.6%) | 10,219 (61.2%) | 62.9% |

| 13–15 y | 2317 (15.6%) | 2559 (15.3%) | 33.3% |

| ≥16 y | 3553 (23.9%) | 3924 (23.3%) | 2.4% |

| Born outside Australia | 3637 (24.4%) | 4090 (24.5%) | 36%b |

| Current smokers | 310 (2%) | 561 (3.4%) | 7%b |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.0 ± 4.6 | 28.0 ± 4.6 | 27.9 ± 5.1c |

Values given as number (percentage of reporting cohort) or mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Compared with Australian population aged 70 y and above, living in Australian states of Victoria, South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory and Tasmania (states from which the majority of ASPREE participants were recruited) from the 2016 Australian Census.

From ‘Older Australians at a Glance’, (Australians aged 65 y + from the ABS 2014–15 NHS).30

Mean BMI of those aged 70 y+ from the 2013/14 Australian National Health Survey.31

The mean age and sex distribution of the ALSOP cohort is similar to the wider ASPREE cohort from which they were drawn (Table 2). The large size of the cohort has provided substantial numbers in a range of key subgroups including age, sex, residence in city/country, and socioeconomic status. As seen in Figure 2, the cohort is skewed slightly toward a higher socioeconomic status compared with the general Australian population aged 70 years (y) and over (as might be expected from the study inclusion criteria being ‘healthy’ at baseline), but still contains good representation across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Figure 2.

Socioeconomic characteristics of the ALSOP cohort and of all Australians aged 70y+. The Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas are derived by the Australian Bureau of Statistics from the Australian Population Census.39 The data presented herein are for deciles of the Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) by postal area. For IRSAD, lower numbers (and deciles) indicate relatively more disadvantage and/or relatively less advantage.

ALSOP is being conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 (including 2008 revision) and the NHMRC Guidelines on Human Experimentation. ALSOP has been reviewed and approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (project numbers CF11/1100 and CF11/1935) and ALSOP participants provide written informed consent to participation.

How often have they been followed up?

Mail-out of second and third waves of ALSOP questionnaires commenced in years 3 and 5, of ASPREE respectively. The composition of each questionnaire has remained largely the same, although some additional questions have been added to the later surveys and some questions were reworded to improve clarity. Table 3 gives the response rates for each wave of ALSOP questionnaires, and illustrates how these align with other data captured for this cohort as part of the ASPREE trial and its ancillary studies. There has been less than 15% attrition at each subsequent ALSOP questionnaire wave. There has been no difference in proportions of gender across the respondents at each wave: the proportions of females returning the year 3 ALSOP Medical and Social questionnaires were 54.5% and 54.4%, respectively, compared with 55% at baseline (Table 2). The questionnaires for ALSOP year 5 were still being administered at time of writing, and final response rates for this wave are not available. The ASPREE trial, from which key health outcome measures for this cohort are drawn, had a low rate of loss to follow-up (3%).9

Table 3.

ASPREE study timeline of trial and ancillary study assessments and data linkages

| Measurement | Year 0 | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5–7 | ASPREE-XTm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–14 | 2011–15 | 2012–16 | 2013–17 | 2014–17 | 2015–18 | 2019- | |

| ASPREE clinical trial | |||||||

| Recruitment/screening | X | ||||||

| Demographics, lifestyle, medications, cardiovascular risk measuresa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Cardiovascular biomarkersb | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Cognitive assessmentsc | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Depression screend | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Quality of lifee | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Physical disability screenf | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Physical functiong | X | X | X | X | |||

| Clinical event recording | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ancillary measuresh | |||||||

| ALSOP Medical Questionnaire (n) | 14 892 | 12 578 | Ongoing | Planned | |||

| ALSOP Social Questionnaire (n) | 13 000 | 10 912 | Ongoing | Planned | |||

| Blood/urine samples (n = 12 228) | X | X | |||||

| Whole genome sequencing (n = 4000) | X | ||||||

| Brain MRIi (n ∼1500) | X | X | X | ||||

| Audiometryj (n = 1267) | X | X | |||||

| Sleep studiesk (n = 1400) | X | X | |||||

| Retinal imagesl (n = 5300) | X | X | X | ||||

| Administrative data linkages | |||||||

| Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS)n (n = 13 500) | X | X | |||||

| Medicare Benefit Schedule (MBS)o (n = 13 500) | X | X | |||||

| Australian National Death Indexp | X | X | |||||

For further information please refer to ASPREE Methodology paper previously published.3 Unless otherwise specified, the numbers are for all reporting ASPREE participants.

Demographic factors include region of residence, socioeconomic classification of residential postcode (SEIFA), blood pressure, heart rate, height, weight, body mass index and abdominal circumference.

Total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), glucose, creatinine (Cr) and haemoglobin, urine albumin: creatinine ratio and microalbuminuria.

3MS, Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Short-Form 12.

Katz ADL scale.

3m Gait Speed and Grip Strength.

Not all ancillary studies capture the complete ASPREE cohort, and all ancillary studies have attrition, usually <10%.

Resting state functional MRI, T1 and T2, white matter whole brain connectivity (using diffusion) and white matter hyperintensities.

Performed using air conduction and bone conduction audiometry.

Limited channel home sleep study providing Apnoea Hyponea Index and Oxygen Desaturation Index.32

Standardized non-mydriatic, colour retinal photograph analysed for vascular calibre changes and age-related macular degeneration.

The ASPREE extension (ASPREE-XT) study is a is a post-treatment, longitudinal observational follow-up study of ASPREE participants for trial endpoints.

The PBS is an Australian government programme funding subsidized medicines for all Australian consumers.

The MBS is an Australian government programme funding subsidized medical services for all Australian consumers.

The Australian National Death Index is the national register of all deaths in Australia (listing date and cause of death).

What has been measured for this cohort?

The composition of each questionnaire is summarized in Tables 4 and 5. Efforts were made to ensure that burden on participants was minimized, by ensuring that the questionnaires were limited to 14 pages with a large font size. A study group including geriatricians, chronic disease clinicians, epidemiologists and data analysts identified key areas of interest, reviewed instruments from other similar cohorts and established instruments of measurement where these were unavailable or unsuitable. Iterations of the questionnaires were completed by test groups of a similar demographic to the ASPREE cohort, with modifications made to ensure ease of completion.

Table 4.

Key areas in the ALSOP Baseline Medical Questionnaire

| Domain | Assessment items |

|---|---|

| Sleep | Set of 10 questions modified from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,33 including sleep duration and frequency of sleep problems |

| Eyesight | Vision is being examined by asking participants to rate their eyesight (with corrective lenses if worn), and its impact on common activities |

| Hearing | Measured by a series of eight questions which include ‘Do you feel you have a hearing loss?',34 use of hearing aids and implants, the social impact of hearing loss and perceived change in hearing over the past 5 years |

| Oral health | An abbreviated set of seven questions derived from the WHO Oral Health Questionnaire35 |

| Bones, joints and falls | A series of questions covering fractures, joint replacement and post-fracture outcomes. Number of falls in the past 12 months and confidence in ability to undertake daily activities without falling |

| Chronic pain | Assessed using a series of five questions on pain, including the presence of daily pain, the severity of pain on a Likert scale, the site of pain, the impact of pain on activities of daily living, sleep and recreation, and the frequency of use of pain medications |

| Polypharmacy and complementary medicines | Set of five questions to examine how prescription medicines are used and managed, and use of common complementary medicines, supplements and vitamins |

| Bowel and bladder | Set of four questions regarding urinary and faecal continence, constipation and nocturia |

| Weight history | Self-reported early adult weight and unintentional weight loss |

Table 5.

Key areas in the ALSOP Baseline Social and Behavioural Questionnaire

| Domain | Assessment items |

|---|---|

| Socioeconomic factors | Socioeconomic variables collected include marital status, country of origin, employment history and retirement, current employment and volunteering, education, income bracket, public and private transport access and housing characteristics, access to domestic assistance services and insurance status |

| Community engagement and social support | Abbreviated set of questions adapted from the Revised Lubben Social Network Scale36 and the Duke Social Support Index37 |

| Physical activity | Self-classification of usual level of activity as (a) inactive, (b) involving no more than light physical activity, (c) involving no more than moderate physical activity or (d) engaged in regular vigorous physical activity. ALSOP also asks participants to classify their level of physical activity in middle age according to the schema described above. A question regarding present participation in strength training activities is also included |

| Adverse life events | A series of 10 questions relating to stressful events over the past year, including death or illness in partners and family members, marriage or partnership breakup, financial difficulties, family conflict, major accidents or death of a pet |

| Optimism | The Revised Life Orientation Test38 |

Questionnaires have been sent by post to participants with post-paid return envelope. At least 2 months have been allowed to elapse between sending the first and second questionnaires at each time point. Participants who have not returned a questionnaire are prompted at the routine follow-up phone calls administered every 3 months as part of the ASPREE trial.

During the course of follow-up, various additional questions have been added to the questionnaires, typically to address areas of increasing social or scientific interest. For example, the 3-year ALSOP follow-up questionnaires included additional questions relating to dietary intake (using a brief 49-item food frequency questionnaire), planning for health decision making in case of incapacity, health service access, financial well-being and decision making, vaccinations for influenza and pneumococcal disease, history of hormone replacement therapy use and family history of longevity. The 5-year questionnaire also captures information on the well-being of those who act as a carer for another person.

The opportunity to leverage from a large clinical trial (ASPREE) with detailed health outcomes and clinical measures is a key strength of ALSOP. The primary outcome measure for ASPREE was a composite endpoint of ‘disability-free life', which incorporates mortality, onset of dementia or persistent disability in at least one of the Katz Activities of Daily Living.9 Secondary endpoints of ASPREE included all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events, cancer, dementia, mild cognitive impairment, depression, physical disability and clinically significant bleeding. A detailed description of the ASPREE trial methodology5 baseline characteristics,5 and major trial outcomes9–11 have been published elsewhere.

The questionnaire responses to ALSOP will also be linked to other information collected during the course of the ASPREE clinical trial and its substudies. This includes detailed information about the health trajectory of individuals, derived from access to medical records with pre-specified morbidity and mortality endpoints confirmed by expert adjudication panels. This allows valuable oversight of the link between the onset of chronic disease and its impact on disability and other aspects of health and social functioning.

Subgroups of the ALSOP cohort have also participated in additional ASPREE substudies involving specific measures such as magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, and auditory and retinal assessments (Table 3). More than 70% of Australian ASPREE participants have donated blood and urine specimens to the ASPREE biorepository, which will allow for future genetic, biomarker and clinical analyses. Most participants have also provided signed consent for their data to be linked to various administrative databases, including the Australian Government Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS) and Medicare Benefit Schedule (MBS), further enhancing the value of the ALSOP data.

Strengths and weaknesses of ALSOP

Embedding ALSOP within a large-scale clinical trial confers substantial strengths and some limitations on its value as a cohort study with broad applicability to elderly Australians. Most importantly, it provides the opportunity to develop observational data of high quality at a marginal additional cost. Without the leverage provided by the underlying clinical trial, it is unlikely that an Australian research resource of similar quality could be developed.

Several of the strengths of ALSOP are fundamental requirements for high-quality epidemiology. For example, the detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria and the high rate of questionnaire completion have provided a clear indication of the population to whom the ALSOP results can be generalized. Equally importantly, the underpinning ASPREE trial has experienced a very low rate of loss to follow-up, presently of the order of 3% for Australian ASPREE participants, providing good access to long-term survival and outcome data. The attrition rate for completion of questionnaires between the first and second rounds of ALSOP is ∼10%. High attrition rates reduce the validity of cohort study findings and are a potential problem with older age cohorts with their increased likelihood of developing disability and cognitive impairment, factors consistently associated with greater risk of study ‘drop-out’.12 Intensive efforts are needed to minimize loss to follow-up in longitudinal cohort studies of older participants, and the combination of annual visits and 3-monthly phone contacts incorporated within the underlying ASPREE protocol have contributed to maintaining a high participation rate in ALSOP.

Another strength of ALSOP is the ability to link the questionnaire data to objective and reliable clinical information obtained at annual in-person reviews and from access to clinical records from the principal ASPREE trial. Detailed cognitive testing and disability assessments will provide an opportunity to observe the impact of developing physical and cognitive impairments on other aspects of health and social functioning.

A limitation conferred by the use of the clinical trial cohort is the extent of generalizability of the results to the wider elderly population. ASPREE is a primary prevention trial, and the exclusion criteria included those with established vascular disease, a contraindication to the use of aspirin, pre-existing dementia or disability, or the presence of an illness that would compromise survival for 5 years. These criteria have resulted in a relatively ‘healthy’ ALSOP cohort at baseline, with a bias towards recruitment of individuals of higher socioeconomic status (Figure 2). The ALSOP cohort is therefore most likely to reflect the health experiences of individuals entering older age in a relatively healthy state. Over time however, it is expected that with the development of chronic disease, the cohort will increasingly become representative of the general elderly population in Australia.

ALSOP will make a significant contribution to addressing some of the previously identified knowledge gaps in healthy ageing research3 and will provide contemporary information on the relationship between lifestyle characteristics, social circumstances and general health in older adults.

What has ALSOP found?

At time of writing, there have been no publications arising from ALSOP data, although a number of projects, including some examining sleep, complementary medicine use and diet in older age, are ongoing. Examples of baseline health and well-being measures collected in ALSOP are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

ALSOP cohort baseline self-reported health and well-being characteristics

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 6752 | 8140 |

| Hours of sleep ≤6h | 18.5% | 24.9% |

| Experience sleeping problems (often or always) | 13% | 23.4% |

| Excellent or good self-rated eyesight | 80.1% | 79.9% |

| Take medication for pain (often/always) | 14.7% | 24.8 % |

| Daily use of vitamin D supplements | 18.3% | 46.2% |

| Excellent or very good self-rated oral health | 48.9% | 53.9% |

| Have had at least one fall in the past year | 23.3% | 33.2% |

| Do not feel confident using steps or public transport without falling | 1.4% | 4.2% |

| Urinary incontinence (often/always) | 16.0% | 24.3% |

| Experienced medication side effects in past year | 6.5% | 10.7% |

| Are able to stay comfortable/seek relief in hot weather (usually/always) | 95.9% | 93.1% |

Values given as percentage of reporting cohort by sex.

Data access and collaboration with ALSOP

All data management for ALSOP is conducted by the ASPREE data management team. Access to ALSOP data is granted by the ALSOP Steering Committee, and prospective studies are reviewed by the ASPREE Presentations, Publications and Ancillary Studies Committee. Potential collaborators should in the first instance discuss ideas informally with the ALSOP principal investigator (J.McN.) before any formal application for data access is made [aspree.ams@monash.edu]. Further information on ASPREE, ALSOP and associated ancillary studies can be accessed via the ASPREE website [www.aspree.org]. ASPREE is registered on clinicaltrials.org at NCT01038583.

Profile in a nutshell

ALSOP is a longitudinal cohort study running in parallel with the Australian component of the ASPREE clinical trial of low-dose aspirin. Its goal is to contribute to identification of new strategies to maintain the health and well-being of older Australians.

A total of 14 892 initially healthy adults, aged 70 years and over, have completed questionnaires focusing on a broad range of general health, lifestyle, behavioural, social, economic and environmental factors relevant to healthy ageing.

With baseline assessments undertaken in the period 2010-14, ALSOP questionnaires have been administered during years 1, 3 and 5 of follow-up of the ASPREE trial cohort, with ongoing follow-up planned.

For collaboration/data access, initial discussion with the ALSOP principal investigator (J.McN.) should be undertaken before a formal application for ALSOP data access through the ASPREE Access Management Team: [aspree.ams@monash.edu].

Acknowledgements and declarations

The ALSOP writing team gratefully acknowledge the contribution of ALSOP participants, the many colleagues who provided advice for the development and refinement of the questionnaires over the course of the development of ALSOP, and the ASPREE administration team for their printing, posting and scanning of ALSOP questionnaires. Aaron Ham is especially acknowledged for leading management of the administration and questionnaire mail-out for ALSOP.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from Monash University, ANZ Trustees, the Wicking Trust and the Mason Foundation. The ASPREE trial was funded by: the US National Institute on Aging and the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant number U01AG029824); the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grant numbers 334047, 1127060); Monash University (Australia); and the Victorian Cancer Agency (Australia).

References

- 1.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Mortality over the Twentieth Century in Australia: Trends and Patterns in Major Causes of Death. Mortality Surveillance Series no. 4. Canberra: AIHW, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prime Minister’s Science, Engineering and Innovation Council Independent Working Group. Promoting Healthy Ageing in Australia. Canberra, Australia: Department of Education, Science and Training, 2003. https://archive.industry.gov.au/science/PMSEIC/Documents/PromotingHealthyAgeing.pdf (3 September 2016, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Curtis AJ, Ofori-Asenso R, Gambhir M, McNeil JJ.. Mortality among middle-aged Australians, 1960-2010: implications for prevention policy. Med J Aust 2018;208:444–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stanziano DC, Whitehurst M, Graham P, Roos BA.. A review of selected longitudinal studies on aging: past findings and future directions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58(Suppl 2):S292–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ASPREE. Study design of ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE): a randomized, controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;36:555–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teng EL, Chui HC.. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48:314–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Katz S, Akpom CA.. A measure of primary sociobiological functions. Int J Health Serv 1976;6:493–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR. et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the ASPREE (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017;72:1586–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR. et al. Effect of aspirin on disability-free survival in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL. et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1519–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL. et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chatfield MD, Brayne CE, Matthews FE.. A systematic literature review of attrition between waves in longitudinal studies in the elderly shows a consistent pattern of dropout between differing studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown WJ, Bryson L, Byles JE. et al. Women’s Health Australia: recruitment for a national longitudinal cohort study. Women Health 1998;28:23–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Banks E, Redman S, Jorm L. et al. Cohort Profile: The 45 and Up study. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:941–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Luszcz MA, Giles LC, Anstey KJ, Browne-Yung KC, Walker RA, Windsor TD.. Cohort Profile: The Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ALSA). Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:1054–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ellis KA, Bush AI, Darby D. et al. The Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging: methodology and baseline characteristics of 1112 individuals recruited for a longitudinal study of Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2009;21:672–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sachdev PS, Lee T, Wen W. et al. The contribution of twins to the study of cognitive ageing and dementia: the Older Australian Twins Study. Int Rev Psychiatry 2013;25:738–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sachdev PS, Brodaty H, Reppermund S. et al. The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study (MAS): methodology and baseline medical and neuropsychiatric characteristics of an elderly epidemiological non-demented cohort of Australians aged 70-90 years. Int Psychogeriatr 2010;22:1248–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Browning CJ, Kendig H.. Cohort Profile: The Melbourne Longitudinal Studies on Healthy Ageing Program. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simons LA, McCallum J, Simons J. et al. The Dubbo study: an Australian prospective community study of the health of elderly. Aust NZ J Med 1990;20:783–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Norman PE, Flicker L, Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Hyde Z, Jamrozik K.. Cohort Profile: The Health In Men Study (HIMS). Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tan HE, Lan NSR, Knuiman MW. et al. Associations between cardiovascular disease and its risk factors with hearing loss - A cross-sectional analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 2018;43:172–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mitchell P, Smith W, Attebo K, Wang JJ.. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy in Australia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology 1995;102:1450–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Jorm AF. et al. The Canberra Longitudinal Study: Design, aims, methodology, outcomes and recent empirical investigations. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 2004;11:169–95. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anstey KJ, Christensen H, Butterworth P. et al. Cohort Profile: The PATH through life project. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:951–60. Aug; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Travers C, O’Neill SM, King R, Battistutta D, Khoo SK.. Greene climacteric scale: norms in an Australian population in relation to age and menopausal status. Climacteric 2005;8:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bennett HP, Piguet O, Grayson DA. et al. A 6-year study of cognition and spatial function in the demented and non-demented elderly: the Sydney Older Persons Study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2003;16:181–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McEvoy M, Smith W, D'Este C. et al. Cohort Profile: The Hunter Community Study. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39:1452–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cumming RG, Handelsman D, Seibel MJ. et al. Cohort Profile: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project (CHAMP). Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:374–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Australian Institute for Health and Welfare. Older Australia at a Glance, 2017. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-statistics/population-groups/older-people/overview (28 May 2018, date last accessed).

- 31.Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: First Results, 2014–15 ABS catalogue number 4364.0.55.001, 2015. www.abs.gov.au (23 May 2018, date last accessed).

- 32. Ward SA, Storey E, Woods RL. et al. The study of neurocognitive outcomes, radiological and retinal effects of aspirin in sleep apnoea - rationale and methodology of the SNORE-ASA study. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;64:101–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Hoch CC, Yeager AL, Kupfer DJ.. Quantification of subjective sleep quality in healthy elderly men and women using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Sleep 1991;14:331–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sindhusake D, Mitchell P, Smith W. et al. Validation of self-reported hearing loss. The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:1371–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. 5th edn. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lubben J, Gironda M, Measuring social networks and assessing their benefits. In: Phillipson C, Allan G, Morgan D (eds). Social Networks and Social Exclusion: Sociological and Policy Perspectives. Farnham UK: Ashgate, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pachana NA, Smith N, Watson M, McLaughlin D, Dobson A.. Responsiveness of the Duke social support sub-scales in older women. Age Ageing 2008;37:666–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW.. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1994;67:1063–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) Canberra: ABS, 2011.