Abstract

Glia are key regulators of inflammatory responses within the central nervous system (CNS) following infection or trauma. We have previously demonstrated the ability of activated astrocytes to rapidly produce pro-inflammatory mediators followed by a transition to an anti-inflammatory cytokine production profile that includes the immunosuppressive cytokine interleukin (IL)-IO and the closely related cytokines IL-19 and IL-24. IL-20, another member of the IL-10 family, is known to modulate immune cell activity in the periphery and we have previously demonstrated that astrocytes constitutively express the cognate receptors for this cytokine. However, the ability of glia to produce IL-20 remains unclear and the effects of this pleiotropic cytokine on glial immune functions have not been investigated. In this study, we report that primary murine and human astrocytes are not an appreciable source of IL-20 following challenge with disparate bacterial species or their components. Importantly, we have determined that astrocyte are responsive to the immunomodulatory actions of this cytokine by showing that recombinant IL-20 administration upregulates microbial pattern recognition receptor expression and induces release of the inflammatory mediator IL-6 by these cells. Taken together, these data suggest that IL-20 acts in a dissimilar manner to other IL-10 family members to augment the inflammatory responses of astrocytes.

Keywords: Interleukin-20, Interleukin-10, Astrocytes, Neuroinflammation, Bacterial Infection

INTRODUCTION

Resident cells of the central nervous system (CNS) including astrocytes and microglia play a major role in the recognition of pathogens and are responsible for the initiation of neuroinflammation following infection. Such glial cells express numerous membrane-associated and cytosolic innate immune receptors including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), either constitutively or following challenge, that allow them to detect invading pathogens (as discussed in [1]). Following activation, microglia and astrocytes rapidly produce an array of soluble immune factors that include the canonical inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 [2–5]. Such responses result in leukocyte recruitment and their activation upon arrival at the site of infection, and are important for pathogen clearance [6,7], but can also be detrimental if they are too severe or sustained. However, it is becoming apparent that other less studied cytokines are produced by glia that have the potential to regulate neuroinflammation.

It is now recognized that IL-10 is just one member of a family of cytokines that includes IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24, and IL-26 [8], which are grouped together based upon their structural homology and sharing of common receptor subunits. Unlike IL-10, the functions of these other family members are not well defined in general, and their role in the CNS is largely unknown (as we review in [9]). Recently, we have demonstrated that IL-19 and IL-24, like IL-10, are expressed in a delayed manner by astrocytes following bacterial challenge and act on glial cells in an immunosuppressive manner [10,11]. Another IL-10 family member, IL-20, has also been suggested to be produced by CNS cells. This cytokine has been reported to be expressed by glioblastoma cells, and IL-20 associated staining has been observed in glia-like cells in an in vivo murine model of ischemic stroke [12]. Furthermore, bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been shown to induce the expression of mRNA encoding IL-20 in mixed glial cell cultures, an effect that was demonstrated to be myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) dependent consistent with induction occurring via TLR4 signaling [13]. Interestingly, our laboratory and another group have reported that murine astrocytes express the subunits that constitute the type 1 [11,14] and type 2 [10] IL-20 receptors, suggesting that these cells could be susceptible to the effects of this cytokine.

In the current study, we have investigated whether glia can express IL-20, either constitutively or following activation. In contrast to IL-10, IL-19, and IL-24, we report that astrocytes are not a significant source of this cytokine following challenge with disparate bacterial species or their components. However, we have determined that primary astrocytes are responsive to the immunomodulatory actions of IL-20 by demonstrating an upregulation in the expression of TLR microbial pattern recognition receptors and the cytokines IL-1β and IL-6 in response to recombinant IL-20 administration. Taken together, these data suggest that IL-20, when produced by non-astrocytic CNS cells or infiltrating leukocytes, acts in a dissimilar manner to other IL-10 family members to augment potentially detrimental inflammatory astrocyte responses.

METHODS

Murine glial cell isolation and culture

Primary murine glial cells were isolated as described previously by our laboratory [3,7,10,11,15]. Briefly, six to eight neonatal C57BL/6J mouse brains per preparation were dissected free of meninges and large blood vessels and finely minced with sterile surgical scissors. The minced tissue was then forced through a wire screen and briefly incubated with 0.25% trypsin-1 mM EDTA in serum free RPMI 1640 medium for 5 minutes. The cell suspension was then washed and this mixed glial culture was maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin mix for 2 weeks. Astrocytes were isolated from mixed glial cultures by mild trypsinization (0.25% trypsin-1 mM EDTA for 20 minutes) in the absence of FBS as previously described [10,16]. The remaining intact layer of adherent cells was demonstrated to be >98% microglia by immunohistochemical staining for the microglial surface marker CD11b [10,16] and the isolated astrocytes were determined to be >96% pure based on morphological characteristics and the expression of the astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) as determined by immunofluorescence microscopy [15]. Microglia were maintained for 1 week in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 20% conditioned medium from LADMAC cells (ATCC CRL-2420), a murine monocyte-like cell line that secretes colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) [17], while astrocytes were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS. In some experiments, the murine macrophage-like cell line RAW 264.7 (ATCC TIB-71) and primary murine bone marrow derived macrophages were studied for comparison purposes. Primary macrophages were isolated and maintained as previously described by our laboratory [18,19]. All studies were performed in accordance with relevant federal guidelines and institutional policies regarding the use of animals for research purposes.

Source and propagation of human glial cell lines and primary cells

Primary cortical human astrocytes were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA) and were cultured in medium supplied by the vendor. The human microglial cell line, hpglia, was a kind gift from Dr. Jonathan Kam (Case Western Reserve University). These cells were derived from primary human cells transformed with lentiviral vectors expressing SV40 T antigen and hTERT, and have been classified as microglia due to their microglia-like morphology, migratory and phagocytic activity, presence of the microglial cell surface markers CD11b, TGFβR, and P2RY12, and characteristic microglial RNA expression profile [20]. This cell line was maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 5% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin.

Bacterial propagation

Neisseria meningitidis strain MC58 (ATCC BAA-335) was grown on Columbia agar plates supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and cultured in Columbia broth (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) on an orbital rocker at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight prior to in vitro challenge. A clinical isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae strain CDC CS109 (ATCC 51915) was grown on commercially available trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood (BD Biosciences) and cultured overnight in tryptic soy broth in a similar manner to that described for N. meningitidis. Staphylococcus aureus strain UAMS-1 (ATCC 49230) was grown from frozen stock on lysogeny broth (LB) agar plates then cultured in tryptic soy broth overnight as described above. The number of colony forming units (CFU) for each bacterial species was determined by spectrophotometry using a Genespec3 spectrophotometer (MiraiBio Inc., Alameda CA).

In vitro bacterial infection of glia and exposure to bacterial components or recombinant IL-20

Glial cells were exposed to bacteria at multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 1:1, 1:10, or 1:50 glia to bacteria in antibiotic free medium for 2 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2. These doses were employed as these bacterial numbers are within the range previously reported for the cerebral spinal fluid of children with bacterial meningitis [21]. Following this incubation period, complete RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin (MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to kill extracellular bacteria [11]. Alternatively, glial cells were exposed to bacterial LPS isolated from Escherichia coli (MilliporeSigma), bacterial flagellin isolated from Salmonella typhimurium strain 14028 (Enzolife Sciences, Farmingdale, NY), or the inflammatory neuropeptide substance P (Sigma Aldrich). In some experiments, glia were treated with commercially available recombinant murine IL-20 protein (R&D Systems) at concentrations of 1, 10, 30, or 100 ng/ml. While levels of IL-20 in the CNS in health and disease remain unclear, Hsu and co-workers have reported median IL-20 levels of 432 ng/ml and 100 ng/ml in the synovial fluid and sera of rheumatoid arthritis patients, respectively [22]. At the indicated time points following bacterial challenge or IL-20 treatment, RNA was isolated for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and culture medium was collected for ELISA and immunoblot analysis.

RNA extraction and semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured glial cells using Trizol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and quantified using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. All RNA samples were diluted to the same concentration and reverse transcribed in the presence of random hexamers using 200 U of RNase H minus Moloney leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI) in the buffer supplied by the manufacturer. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed on 5% of the reverse-transcribed cDNA product to assess the relative levels of expression of mRNA-encoding IL-20, TLR4, TLR5, IL-6, IL-1β and the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Table 1). Primers were designed spanning multiple exons using either Primer-BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD) or Primer3 web interface [23]. RT-PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels and imaged using Bio-Rad EZ imaging system and densitometric analysis was performed using ImageLab software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Table 1:

PCR primer sequences

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| hIL-20 | TTGAATTCCTAGCTCCTGTGG | CGATTCGCAGGCTTTGTGTC |

| mIL-20 | CGGGATAGTGTGCAAGCTGAAG | GCCATGTGCAGAATGACAGACTG |

| GAPDH | CCATCACCATCTTCCAGGAGCGAG | CACAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTCAT |

| TLR4 | CAAGTTTAGAGAATCTGGTGGCTGTGG | TGAAAGGGCTTGGTCTTGAATGAAGTCA |

| TLR5 | CCAGAACATCAGAGATCCTGA | CCAATGGCCTTAAGAGCATTG |

| IL-6 | AGAGTTGTGCAATGGCAATTCT | CCTTCTGTGACTCCAGCTTATCTG |

| IL-1β | ATGGCAACTGTTCCTGAACT | GTATTGCTTGGGATCCACACT |

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis for the presence of secreted IL-20 in cell culture medium was performed as described previously by our laboratory [10]. After incubation with either a polyclonal goat IgG antibody directed against mouse IL-20 (R&D Systems, AF1204) or a polyclonal goat IgG directed against human IL-20 (R&D Systems, AF1102) for 24 hours at 4°C, blots were washed and incubated in the presence of an appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Bound enzyme was detected with Advansta Western Bright enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Advansta, Menlo Park, CA) with a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). To assess total protein loading in each well, an irrelevant protein on Coomassie blue stained gels was used as a loading control. Immunoblots shown are representative of at least three separate experiments and ImageLab software (Bio-Rad) was used for densitometric analysis. IL-20 levels are reported relative to levels in unstimulated cells normalized to an unrelated loading control.

Quantification of IL-1β. IL-6. and IL-20. in glial cell culture supernatants

Murine IL-1β and IL-20 release was quantified using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems). A specific capture ELISA was performed to quantify release of murine IL-6 using a rat anti-mouse IL-6 capture antibody (Clone MP5-20F3; BD Biosciences) and a biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-6 detection antibody (Clone MP5-C2311). Bound antibody was detected by addition of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (BD Biosciences). After addition of TMB substrate and H2SO4 stop solution, absorbances were measured at 450 nm using a Tecan Sunrise™ (Tecan Group, Männedorf, Switzerland) microplate reader. A standard curve was constructed using varying dilutions of recombinant IL-6 (BD Biosciences) and the cytokine content of culture supernatants determined by extrapolation of absorbances to the standard curve.

Statistical analysis

Data is presented as the mean +/− standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test using commercially available software (GraphPad Prism, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). In all experiments, results were considered statistically significant when a P-value of less than 0.05 was obtained.

RESULTS

Astrocytes are not a significant source of IL-20 following bacterial stimulation

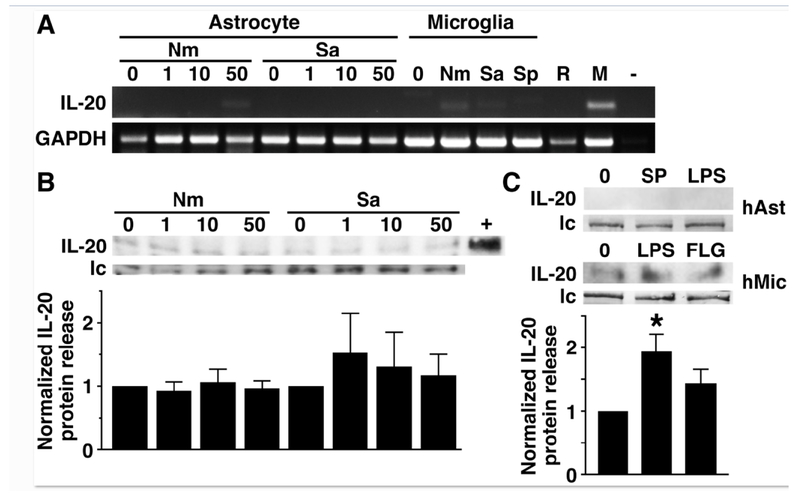

To begin to determine whether astrocytes can express IL-20, we have assessed in vitro IL-20 mRNA expression in isolated primary murine astrocytes by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 1A, murine astrocytes do not constitutively express IL-20 mRNA and do not express significant levels of mRNA encoding this cytokine following exposure to Gram-negative N. meningiditis or Gram-positive S. aureus at 6 hours post challenge, or earlier (data not shown). In contrast, primary murine microglia showed low level but detectable IL-20 RNA expression following exposure to bacteria such as N. meningitis (Figure 1A: 107.6 versus 15.3 arbitrary densitometric units normalized to GAPDH expression in microglia and similarly infected astrocytes, respectively), and primary but not immortalized murine macrophages expressed mRNA encoding this cytokine following activation with bacterial LPS (Figure 1A: 184.2 arbitrary densitometric units normalized to GAPDH expression). Consistent with these findings, astrocytes failed to express detectable levels of IL-20 protein release either at rest or 10, 24, or 48 hrs following bacterial challenge infection as determined by commercially available ELISA (data not shown) or an immunoblot detection method (Figure 1B and data not shown).

FIGURE 1:

Murine and human astrocytes fail to express significant levels of IL-20 mRNA or protein, either constitutively or following bacterial stimulation. Primary murine (Panels A and B) and human (Panel C) astrocytes (3 X 105 cells per well) were untreated (0) or challenged with N. meningiditis (Nm), S. aureus (Sa) or S. pneumoniae (Sp) at the indicated MOI or the inflammatory neuropeptide substance P (SP; 5 nM) or bacterial LPS (5 ng/ml). Panel A: At 6 hours post challenge, IL-20 mRNA expression was determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Expression of GAPDH mRNA housekeeping gene product is included and the image shown is representative of at least three independent experiments. For comparison purposes, IL-20 mRNA expression was also determined in primary murine microglia at 8 hrs following challenge with N. meningiditis (Nm), S. aureus (Sa) or S. pneumoniae (Sp) at a MOI of 10:1 bacteria to cells, and RAW264.7 murine macrophage-like cells (R) and primary murine macrophages (M) stimulated with LPS (5 ng/ml). A blank PCR reaction control is also shown (−). Panel B: At 10 hrs, cell medium was collected and analyzed for IL-20 protein content by immunoblot analysis. Expression of an irrelevant protein is shown as a loading control (lc) and recombinant IL-20 (40 pg) is shown as a positive control (+). The relative IL-20 expression was determined by densitometric analysis, normalized to untreated cells, and shown graphically below. Data is expressed as the mean +/− the SEM of 5 independent experiments and no statistically significant differences were observed from untreated cells. Panel C: At 24 hrs, IL-20 protein release by primary human astrocytes (hAst) or an immortalized human microglial cell line (hMic) was determined by immunoblot analysis and expression of an irrelevant protein is shown as a loading control (lc). Relative IL-20 expression was determined by densitometric analysis, normalized to untreated cells, and shown graphically below. Data is expressed as the mean +/− the SEM of 3 independent experiments and asterisk indicates a statistical significance compared to unchallenged cells (p < 0.05).

In addition, we have assessed the ability of human glia to release IL-20 protein and show that primary human astrocytes similarly fail to produce any detectable IL-20 either constitutively or following exposure to bacterial LPS or the inflammatory neuropeptide substance P (Figure 1C). In contrast, low level IL-20 protein production was seen in cultures of resting human microglia-like cells and such expression was significantly increased following challenge with bacterial LPS (Figure 1C).

IL-20 upregulates TLR and inflammatory cytokine expression by astrocytes

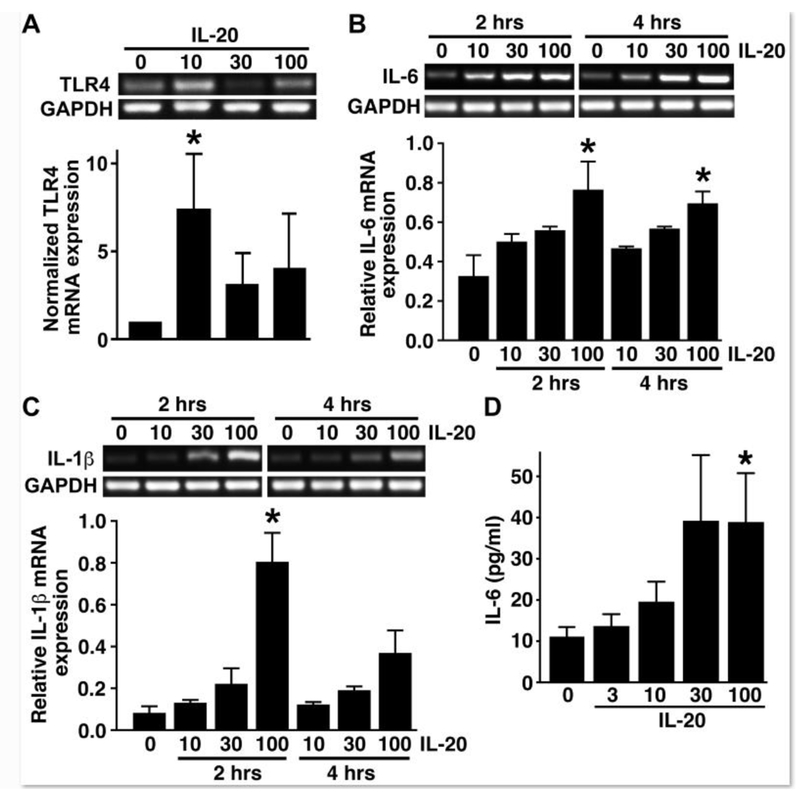

We and others have previously demonstrated that murine astrocytes express the cognate IL-20 receptor subunits for the type I and type II IL-20 receptors, IL-20R1 and IL-20R2 and IL-22R1 and IL-20R2, respectively, suggesting that astrocytes are responsive to this cytokine [10,11]. To directly assess the ability of primary astrocytes to respond to IL-20, we exposed cells to recombinant murine IL-20 protein and assessed its effect on inflammatory innate immune molecule expression. As shown in Figure 2A, IL-20 elicited significant increases in the level of expression of mRNA encoding the pattern recognition receptor for bacterial LPS, TLR4, in astrocytes as rapidly as 2 hrs following treatment. IL-20 elicited a similar trend in the expression of mRNA encoding TLR5, the innate immune receptor for bacterial flagellin, but this effect showed greater variability than that for TLR4 mRNA and failed to reach statistical significance (data not shown).

FIGURE 2:

Primary astrocytes are functionally responsive to the proinflammatory effects of IL-20. Panel A: Murine astrocytes were unstimulated or exposed to recombinant IL-20 (10, 30, or 100 ng/ml) for 2 hours and levels of mRNA encoding TLR4 were determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Expression relative to densitometric analysis of house-keeping gene GAPDH expression is shown graphically below. Panels B and C: Cells were unstimulated or stimulated with 10, 30, or 100 ng/ml IL-20 for 2 or 4 hours prior to total RNA isolation. Pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression was analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR for IL-6 (Panel B) and IL-1β (Panel C). Densitometric analysis was performed and gene expression relative to GAPDH levels are shown below. Panel D: Cells were unstimulated or stimulated with recombinant murine IL-20 (3, 10, 30, or 100 ng/ml) for 12 hours and a specific capture ELISA was used to determine the level of IL-6 release. Asterisk denotes statistical significance compared to unchallenged cells (n = 11; p < 0.05).

In addition to the ability of IL-20 to upregulate the expression of innate immune receptors, we have determined that this IL-10 family member can also elicit the rapid expression and release of key inflammatory cytokines by astrocytes. As shown in Figure 2B, 2 hr exposure of murine astrocytes to recombinant IL-20 induced a marked increase in the expression of mRNA encoding the inflammatory cytokine IL-6, and such increases were sustained up to 4 hours following treatment. This effect was not limited to IL-6 as IL-20 similarly induced a rapid upregulation in mRNA expression of another canonical inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β (Figure 2C). Finally, we have confirmed that exposure of astrocytes to IL-20 was a full and sufficient stimulus to promote inflammatory cytokine protein production with the demonstration that treatment with recombinant cytokine elicited measurable IL-6 release at 12 hours following exposure in a dose dependent manner (Figure 2D). Interestingly, while IL-20 elicited robust increases in IL-1β mRNA expression, it was not a sufficient stimulus to elicit mature IL-1β protein release as determined by specific capture ELISA (data not shown). Together, these data are consistent with an ability of IL-20 to induce or augment inflammatory astrocyte responses.

DISCUSSION

It is now well recognized that resident glia play a critical role in the initiation and progression of inflammatory responses within the CNS following infection. This is achieved by the recognition of microbial motifs via cytosolic and membrane associated pattern recognition receptors and the subsequent production of an array of inflammatory mediators. Importantly, such glial responses can be exacerbated or mitigated by cytokines produced by infiltrating leukocytes or the glial cells themselves in an autocrine or paracrine manner.

We have recently demonstrated that glial cells produce members of the IL-10 family of cytokines following bacterial challenge and are responsive to the immunomodulatory effects of these cytokines. Specifically, we have shown that stimulated astrocytes release IL-10, IL-19, and IL-24, in a delayed manner [10,11,24], and such production appears to occur secondary to the release of soluble factors from bacterially challenged glial cells [24]. In contrast, in the present study we have determined that murine and human astrocytes do not appear to be an appreciable source of another IL-10 family member, IL-20, either constitutively or following exposure to disparate bacterial pathogens of the CNS or their components. This finding differs from the previous demonstration of IL-20 expression by an astrocytic glioblastoma cell line [12], perhaps reflecting the differences between these immortalized cells and primary astrocytes. Our detection of IL-20 production by microglia, albeit at modest levels, is consistent with the reported expression of this cytokine by myeloid cells following stimulation with TLR ligands [25], and may account for the presence of IL-20 associated staining in the brain tissue of mice following ischemic challenge [12] and the detection of mRNA encoding IL-20 in mixed glial cell cultures following TLR4-mediated activation [13].

We have shown that glia constitutively and inducibly express receptors for IL-10, IL-19 and IL-24, and we demonstrated that all three cytokines can limit inflammatory mediator production by astrocytes following exposure to clinically relevant bacterial pathogens [10,11,24]. IL-20 can signal through two different heterodimeric receptors, IL-20 receptor types 1 and 2, which are composed of IL-20R1 and IL-20R2, and IL-22R1 and IL-20R2 subunits, respectively [8,26], and we and others have previously shown that murine astrocytes express both of these receptors [10,11]. Interestingly, and in contrast to the other members of the IL-10 family, we found that administration of IL-20 can directly induce release of the canonical inflammatory cytokine IL-6 by primary astrocytes. Such a finding is consistent with a previous report that IL-20 can elicit release of the inflammatory chemokines MCP-1 and IL-8 by a human astrocytic cell line [12]. Interestingly, while IL-20 elicited robust increases in IL-1β mRNA expression, it was not a sufficient stimulus to elicit mature protein release as determined by specific capture ELISA, suggesting that a second stimulus such as a damage associated molecular pattern (DAMP) might be required, as discussed elsewhere [27]. Additionally, we have determined that IL-20 stimulation can upregulate TLR mRNA expression by astrocytes in a similar manner to that previously reported for other IL-10 family members in other cell types [28], suggesting that IL-20 could also prime glia for subsequent bacterial challenge.

In the periphery, elevated IL-20 levels have been detected in the serum of patients with chronic inflammatory disorders, such as psoriasis, and rheumatoid arthritis [8,29], and genetic polymorphisms for this cytokine have been identified as risk factors for such chronic inflammatory diseases [30–32]. Similarly, significantly higher levels of IL-20 mRNA have been found to be associated with wound-associated inflammation in a mouse model of diabetes [33]. Within the CNS, inhibition of IL-20 using a neutralizing antibody has been shown to limit the inflammatory damage associated with acute ischemic brain injury [12]. Importantly, in the context of bacterial infection, IL-20 has recently been reported to be transiently expressed in lung tissue in a mouse model of S. pneumoniae infection, and an IL-20 receptor blocking antibody was shown to significantly reduce pulmonary damage, neutrophil recruitment, and IL-1β and IL-6 levels, associated with such a challenge [34]. Together, these data support the contention that IL-20, perhaps produced by non-astrocytic CNS cells or infiltrating leukocytes, functions to initiate or augment astrocyte inflammatory responses.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Primary murine and human astrocytes are not an appreciable source of IL-20 following challenge with disparate bacterial species or their components.

Primary astrocytes are responsive to IL-20 and show upregulated TLR and IL-1β expression, and IL-6 production, following administration of this cytokine.

IL-20 acts in a dissimilar manner to other IL-10 family members to augment the inflammatory responses of astrocytes.

Acknowledgements:

Funding: This work was supported by grant NS050325 and NS097840 to IM from the National Institutes of Health.

LIST OF NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS

- cDNA

complementary deoxyribonucleic acid

- CFU

colony forming units

- hTERT

human telomerase reverse transcriptase

- LB

lysogeny broth

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- TGFβR

transforming growth factor beta receptor

- TMB

3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Ethics approval: All studies were performed in accordance with relevant federal guidelines and institutional policies regarding the use of animals for research purposes.

Availability of data and material: The data used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- [1].Furr SR, Marriott I, Viral CNS infections: role of glial pattern recognition receptors in neuroinflammation, Front. Microbiol (2012) 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Furr SR, Moerdyk-schauwecker M, Grdzelishvili VZ, Marriott F, F RIG-I mediates non-segmented negative-sense RNA virus-induced inflammatory immune responses of primary human astrocytes, Glia 58 (2010) 1620–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Liu X, Chauhan VS, Young AB, Marriott F, NOD2 mediates inflammatory responses of primary murine glia to Streptococcus pneumoniae, Glia 50 (2010) 839–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Serramía MJ, Muñoz-fernández MÁ, Álvarez S, HIV-1 increases TLR responses in human primary astrocytes, Sci. Rep 5 (2015) 17887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sun Y, Li N, Zhang J, Liu H, Liu J, Xia X, Sun C, Feng X, Gu J, Du C, Han W, Lei L, Enolase of streptococcus suis serotype 2 enhances blood–brain barrier permeability by inducing IL-8 release, Inflammation 39 (2016) 718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Barichello T, Fagundes GD, Generoso JS, Paula Moreira A, Costa CS, Zanatta JR, Simões LR, Petronilho F, Dal-Pizzol F, Carvalho Vilela M, Lucio Teixeira A, Brain-blood barrier breakdown and pro-inflammatory mediators in neonate rats submitted meningitis by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Brain Res 1471 (2012) 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chauhan VS, Sterka DG, Gray DL, Bost KL, Marriott I, Neurogenic exacerbation of microglial and astrocyte responses to Neisseria meningitidis and Borrelia burgdorferi, J. Immunol 180 (2008) 8241–8249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rutz S, Wang X, Ouyang W, The IL-20 subfamily of cytokines-from host defence to tissue homeostasis, Nat. Rev. Immunol 14 (2014) 783–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Burmeister AR, Marriott I, The interleukin-10 family of cytokines and their role in the CNS, Front. Cell. Neurosci 12 (2018) 458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Burmeister AR, Johnson MB, Yaemmongkol JJ, Marriott I, Murine astrocytes produce IL-24 and are susceptible to the immunosuppressive effects of this cytokine, J Neuroinflamm 16 (2019) 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cooley ID, Chauhan VS, Donneyz MA, Marriott I, Astrocytes produce IL-19 in response to bacterial challenge and are sensitive to the immunosuppressive effects of this IL-10 family member, Glia 62 (2014) 818–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen WY, Chang MS, IL-20 is regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor and up-regulated after experimental ischemic stroke, J. Immunol 182 (2009) 5003–5012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hosoi T, Wada S, Suzuki S, Okuma Y, Akira S, Matsuda T, Nomura Y, Bacterial endotoxin induces IL-20 expression in the glial cells, Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res 130 (2004) 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Abd Nikfaijam B, Ebtekar M, Sabouni F, Pourpak Z, Kheirandish M, Detection of IL-20R1 and IL-20R2 mRNA in C57BL/6 mice astroglial cells and brain cortex following LPS stimulation, Iran J. Immunol 10 (2013) 62–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bowman CC, Rasley A, Tranguch SL, Marriott I Cultured astrocytes express toll-like receptors for bacterial products. Glia 43 (2003) 281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Saura J, Tusell JM, Serratosa J, High-Yield Isolation of Murine Microglia by Mild Trypsinization, Glia 44 (2003) 183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].O’Keefe GM, Nguyen VT, Tang LP, Benveniste EN, IFN regulation of class II transactivator promotor IV in macrophages and microglia: Involvement of the suppressors of cytokine signaling-1 protein, J. Immunol 166 (2001) 2260–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chauhan VS, Nelson DA, Marriott I, Bost KL, Alpha beta-crystallin expression and presentation following infection with murine gammaherpesvirus 68, Autoimmunity 46 (2013) 399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Elsawa SF, Taylor W, Petty CC, Marriott I, Weinstock JV, Bost KL, Reduced CTL response and increased viral burden in substance P receptor-deficient mice infected with murine gamma-herpesvirus 68, J. Immunol 170 (2003) 2605–2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Garcia-Mesa Y, Jay TR, Checkley MA, Luttge B, Dobrowolski C, Valadkhan S, Landreth GE, Karn J, Alvarez-Carbonell D. Immortalization of primary microglia: a new platform to study HIV regulation in the central nervous system, J. Neurovirol 23 (2017) 47–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bingen E, Lambert-Zechovsky N, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Doit C, Aujard Y, Foumerie F, Mathieu H, Bacterial counts in cerebrospinal fluid of children with meningitis, Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis 9 (1990) 278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hsu YH, Li HH, Hsieh MY, Liu MF, Huang KY, Chin LS, Chen PC, Cheng HH, Chang MS, Function of interleukin-20 as a proinflammatory molecule in rheumatoid and experimental arthritis, Arthritis Rheum 54 (2006) 2722–2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG, Primer3-new capabilities and interfaces, Nucleic Acids Res 40 (2012) 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rasley A, Tranguch SL, Rati DM, Marriott I, Murine glia express the immunosuppressive cytokine, interleukin-10, following exposure to Borrelia burgdorferi or Neisseria meningitidis, Glia 53 (2006) 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wolk K, Kunz S, Asadullah K, Sabat R, Cutting edge: immune cells as sources and targets of the IL-10 family members? J. Immunol 168 (2002) 5397–5402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ouyang W, Rutz S, Crellin NK, Valdez PA, Hymowitz SG, Regulation and functions of the IL-10 family of cytokines in inflammation and disease, Annu. Rev. Immunol 29 (2011) 71–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Man SM, Karki R, Kanneganti TD, Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis, inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes in infectious diseases, Immunol Rev 277 (2017) 61–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wolk K, Witte K, Witte E, Proesch S, Schulze-Tanzil G, Nasilowska K, Thilo J, Asadullah k., Sterry W, Volk HD, Sabat R, Maturing dendritic cells are an important source of IL-29 and IL-20 that may cooperatively increase the innate immunity of keratinocytes, J. Leukoc. Biol 83 (2008) 1181–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kragstrup TW, Andersen MN, Schiottz-Christensen B, Jurik AG, Hvid M, Deleuran B, Increased interleukin (IL)-20 and IL-24 target osteoblasts and synovial monocytes in spondyloarthritis, Clin. Exp. Immunol 189 (2017) 342–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kõks S, Kingo K, Rätsep R, Karelson M, Silm H, Vasar E, Combined haplotype analysis of the interleukin-19 and -20 genes: relationship to plaque-type psoriasis, Genes Immun 5 (2004) 662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kingo K, Kõks S, Nikopensius T, Silm H, Vasar E, Polymorphisms in the interleukin-20 gene: relationships to plaque-type psoriasis, Genes Immun 5 (2004) 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ermers MJ, Janssen R, Onland-Moret NC, Hodemaekers HM, Rovers MM, Houben ML, Kimpen JL, Bont LJ, IL10 family member genes IL19 and IL20 are associated with recurrent wheeze after respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis, Pediatr. Res 70 (2011) 518–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Finley PJ, DeClue CE, Sell SA, DeBartolo JM, Shornick LP. Diabetic wounds exhibit decreased Ym1 and arginase expression with increased expression of IL-17 and IL-20, Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle) 5 (2016) 486–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Madouri F, Barada O, Kervoaze G, Trottein F, Pichavant M, Gosset P, Production of Interleukin-20 cytokines limits bacterial clearance and lung inflammation during infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae, EBioMedicine 37 (2018) 417–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]