Summary

Neuroimmunology as a separate discipline has its roots in the fields of neurology, neuroscience and immunology. Early studies of the brain by Golgi and Cajal, the detailed clinical and neuropathology studies of Charcot and Thompson’s seminal paper on graft acceptance in the central nervous system, kindled a now rapidly expanding research area, with the aim of understanding pathological mechanisms of inflammatory components of neurological disorders. While neuroimmunologists originally focused on classical neuroinflammatory disorders, such as multiple sclerosis and infections, there is strong evidence to suggest that the immune response contributes to genetic white matter disorders, epilepsy, neurodegenerative diseases, neuropsychiatric disorders, peripheral nervous system and neuro‐oncological conditions, as well as ageing. Technological advances have greatly aided our knowledge of how the immune system influences the nervous system during development and ageing, and how such responses contribute to disease as well as regeneration and repair. Here, we highlight historical aspects and milestones in the field of neuroimmunology and discuss the paradigm shifts that have helped provide novel insights into disease mechanisms. We propose future perspectives including molecular biological studies and experimental models that may have the potential to push many areas of neuroimmunology. Such an understanding of neuroimmunology will open up new avenues for therapeutic approaches to manipulate neuroinflammation.

Keywords: central nervous system, inflammation, neurodegeneration, neuroimmunology, neuroinflammation

Introduction

Neuroimmunology encompasses fundamental and applied biology, immunology, chemistry, neurology, pathology, psychiatry and virology of the central nervous system (CNS). Scientists in the field study the interactions of the immune and nervous system during development, homeostasis and response to injuries with the major aim of developing approaches to treat or prevent neuroimmunological diseases.

The immune system has been generally regarded as autonomous and the brain protected by the blood–brain barrier, (BBB) and in the words of Rudyard Kipling (Barrack‐room ballads, 1892), ‘never the twain shall meet’. In the past decades these dogmas have been strongly challenged and dispelled with the wealth of evidence showing that not only does the nervous system receive messages from the immune system, but that signals from the brain regulate immune functions that subsequently control inflammation in other tissues 1. Communication between the immune system and the CNS is exemplified by the finding that many molecules associated with the immune system are widely expressed and functional in the nervous system and vice versa. Cross‐talk between microglia and neurones is known to be essential for maintaining homeostasis, yet such cross‐talk also occurs between oligodendrocytes and microglia 2. Disturbance in this communication due to peripheral infections in mice are known to trigger microglia activation and augment neurodegeneration 3. Similarly, recent experimental studies show that maternal infections lead to long‐term changes in microglia and abnormal brain development in the offspring 4, 5.

Despite this evidence, it is surprising that the term ‘neuroimmunology’ was only first used on PubMed in 1982, coinciding with the first Neuroimmunology Congress in Stresa, Italy (Fig. 1) and following the launch of the Journal of Neuroimmunology in 1981. Although neuroimmunology research has focused on multiple sclerosis (MS; using the search term ‘neuroimmunology’, 43% of papers on PubMed in 2018 were on MS), immune responses are also observed in Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS), white matter diseases, psychiatric disorders, infections, trauma and neurodegenerative diseases traditionally considered to be ‘cell autonomous’ (Table 1).

Figure 1.

World map showing location of International School of Neuroimmunology (ISNI) meetings.

Table 1.

Neuroimmune diseases

| Disease | Clinical characteristics | Immune involvement | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADEM | Lethargy, visual problems, paralysis associated with viral infection or vaccination | Demyelination, inflammation, axonal loss, hypertrophic astrocytes, activated microglia | 6 |

| ALS motor neurone disease | Fatal motor neurone disease affecting the motor neurones leading to weakness of voluntary muscles | Systemic immune activation, microglia activation and hypertrophic astrocytes. Complement deposition | 7, 8, 9 |

| AD | Progressive cognitive decline. Amyloid plaques, synaptic loss and neurofibrillary tangles. Anti‐inflammatory drugs associated with reduced risk | Microglia, astrocytes, complement and cytokines in plaques. Aβ binds and activates microglia. Aβ reactive T cells in blood, immunoglobulin in CSF | 10, 11 |

| Autoimmune encephalitis | Psychiatric symptoms may predominate | Autoantibodies directed against neuronal surface proteins including adhesion molecules, ion channels and receptors used as biomarkers of disease | 12, 13 |

| CFS | Chronic dysfunction including fatigue, headaches and cognitive impairment | PET imaging shows microglia activation. Immune dysregulation in cytokine profiles and T and B cells, immunoglobulin and natural killer cell cytotoxicity | 14 |

| CNS vasculitis | Fatigue, impaired cognition, speech problems, seizures, paralysis | Inflammation of blood vessels in the CNS | 15 |

| Depression | Anxiety, cognitive impairment, panic attacks. Changes in serotonergic or glutamatergic transmission | Increased T cells and cytokines. Injection of inflammatory mediators, e.g. interleukin‐2 and interferon gamma induce symptoms of depression | 16, 17 |

| Epilepsy | Seizures associated with cognitive and psychological sequelae | Innate and adaptive immune responses. Antibodies deposits on BBB. Anti‐inflammatory agents control forms of epilepsy | 18, 19 |

| GBS | Acute paralytic neuropathy. High cerebrospinal fluid protein levels Disease seen following Zika virus infection | Pathogenic antibodies to gangliosides arise due to molecular mimicry in Campylobacter jejuni lipo‐oligosaccharide infection | 20, 21 |

| HD and other polyQ diseases | Mutant huntingtin protein (or other polyQ) aggregates. Neostriatal atrophy and neuronal loss in putamen and caudate nucleus | Microglia express mutant huntingtin (and other polyQ) protein are dysfunctional. Expression of complement components in associated with severe atrophy | 22 |

| Infections | Encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, meningitis, polyradiculitis or polyneuritis | Immune responses to infectious agent Some viruses induce immunosuppression (e.g. HIV, EBV, Herpes simplex virus) | 23 |

| Leucodystrophies | e.g. X‐ALD: progressive cognitive and motor function impairment and eventually total disability. Accumulated levels of very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) | X‐ALD: severe lymphocytic response. VLCFA impair monocytes. Activated microglia and astrocytes become dystrophic | 24, 25 |

| MS | Relapsing remitting or progressive neurological dysfunction. Oligoclonal cerebrospinal fluid bands | Demyelination and axonal loss in CNS associated with innate and adaptive immune cell activation | 26 |

| MG and other channel‐opathies | Clinical features depend on antibody e.g. synaptic dysfunction, neuronal excitability due to inhibition of ion channel function | Antibody‐mediated disorders of the neuromuscular junction, e.g. antibodies to AChR in MG | 27, 28 |

| Neuromyelitis optica | (Devic’s disease) Inflammatory disorder affecting optic nerves and spinal cord | Presence of antibodies to aquaporin 4 in 80% cases damage astrocytes | 29 |

| Paraneoplastic disorders | Immune mediated disorders triggered by tumour expressing neuronal antigens. Clinical manifestations depend on target of antibody | Disease associated with antibody deposits on neuromuscular junction, Purkinje cell or peripheral nerves. T cells and immunoglobulin in cerebrospinal fluid | 30 |

| Parkinson’s disease | Progressive movement disorder associated with loss of dopaminergic neurones | Microglia and astrocyte activation associated with neuronal loss. IL‐1b gene polymorphisms associated with early onset. CD4+ and CD8 T cells in animal models | 31 |

| SLE, PSS, diabetes, gluten ataxia | SLE: cognitive decline, depression, seizures, chorea. PSS: optic neuritis, vasculitis, results neurological syndrome. Gluten ataxia: cerebellar ataxia and atrophy | SLE: vasculitis, autoantibodies, immune complexes | 30 |

| PSS: inflammation mimicking MS. Gluten ataxia: loss of Purkinje cells associated with immune activation | |||

| Stroke | Blockage of blood vessel or haemorrhage deprives CNS of oxygen resulting in various levels of unconsciousness | Systemic and local inflammation triggered to clear debris | 32 |

| Traumatic spinal injury | Contusions and bruising due to fracture or dislocation leading to paralysis, or degrees of dysfunction below level of injury | Injury triggers inflammation that may contribute to secondary tissue damage | 33 |

| Neuroinfections | |||

| Virus | Clinical characteristics | Neuroimmune involvement | Ref |

| HIV dementia | Cognitive changes | HIV‐infected monocytes and T cells produce chemokines and cytokines | 34 |

| Arbovirus | Depends on infection | Virus infects neurones, local immune response, microglia and macrophages present viral antigens to T cells. Antibodies may control spread | 35, 36 |

| TBE, e.g. Zika | Depends on infection, e.g. Zika virus: microcephaly, GBS and CNS disorders | Role of myeloid cells in facilitating viral spread and pathology | 37 |

| Rabies | Encephalitis | Immune responses crucial to clear neurotrophic virus | 38 |

| HSV | Fever can induce anti‐NMDAR encephalitis | Innate and adaptive immune responses control infection. Virus evades CD8+ T cells. TLR‐3 polymorphisms associated with susceptibility | 39 |

| EBV | Febrile illness, meningeal signs, epileptic insults, depression polyradiculomyelitis, cognitive disorders, encephalitis | EBV‐related lymphomas in CNS. Increased mononuclear leucocytes. Evidence that EBV infection is linked to MS and CFS | 40, 41 |

| SSPE | Fatal complication of measles infection. Latency period of 4–10 years leading to coma | Immaturity of immune response leads to widespread infection | 42 |

CFS = chronic fatigue syndrome; HSV = herpes simplex virus; NMDAR = N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor; PSS = primary Sjögren’s syndrome; SSPE = subacute sclerosing panencephalitis; TBE = tick‐borne encephalitis virus; AChR = acetylcholine receptor; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; ADEM = acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis virus; ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CNS = central nervous system; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; EBV = Epstein–Barr virus; GBS = Guillain–Barré syndrome; HD = Huntington’s disease; MS = multiple sclerosis; MG = myasthenia gravis; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; TLR = Toll‐like receptor.

One of the greatest misconceptions that impeded progress in neuroimmunology was the idea that the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and the perceived immunological privilege of the brain prevent cross‐talk between the CNS and immune systems. This long‐standing dogma has been challenged by recent studies and the discovery of glymphatics and meningeal lymphatic vessels 43. Although this paradigm shift is a recent advancement in thinking of nervous‐immune system cross‐talk, such changes in the field, beginning over 150 years earlier, have been generally linked to technological advances, some of which have yielded Nobel Prizes in neuroimmunology (Table 2), including the development of mutant and transgenic mice to examine disease mechanisms, stem cell technologies and the novel CRISPR/cas9 system, that allows gene editing enabling personalized treatments.

Table 2.

Nobel prizes relevant to the field of neuroimmunology

| Year | Recipient | Topic | Influence on neuroimmunology field |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | Emile A. Behring | Serum therapy | Opened a new road in medical science for treating diseases |

| 1906 | Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramón y Cajal | Structure of the nervous system | Impregnation method allowed microscopy of neuroglia |

| 1908 | Ilya I. Metchnikoff and Paul Ehrlich | Recognition of work on immunity. Metchnikoff discovered types and functions of phagocytes. Ehrlich identified types of blood leucocytes | Formulating the concept of antibody: antigens complexes |

| Antibodies are the foundation for immunohistochemistry and for some therapies | |||

| 1919 | Jules Bordet | Discoveries relating to immunity | Interaction of antibodies and complement. Of diagnostic importance and understanding mechanisms of cell death |

| 1927 | Julius Wager‐Jauregg | Therapeutic value of malaria inoculation in the treatment of dementia paralytica | The link between infection, inflammation and neurological diseases |

| 1945 | Alexander Fleming, Ernst B. Chain and Howard W. Florey | Discovery of penicillin and treatment for various infectious diseases | Key approach to managing bacterial infections including central nervous system (CNS) diseases, e.g. brain abscesses |

| 1951 | Max Theiler | Yellow fever and how to combat it | Controlling arboviruses using live attenuated viruses. Paved the way for controlling neurotrophic viruses |

| 1953 | Watson and Crick | Structure of DNA | Understanding genetic disorders and potential of gene therapy |

| 1954 | John F. Enders, Thomas H. Weller and Frederick C. Robbins | Ability of poliomyelitis viruses to grow in cultures of various types of tissue | In‐vitro testing of vaccines, neutralizing antibodies, typing infectious agents and cytopathic effects |

| 1960 | Frank Macfarlane Burnet and Peter B. Medawar | Acquired immunological tolerance | Self/non‐self‐discrimination led to approaches to induce tolerance to self‐antigens in neuroinflammatory diseases |

| 1972 | Gerald M. Edelman and Rodney R. Porter | Discoveries concerning the chemical structure of antibodies | Role of antibodies in disease, use in technologies, e.g. vaccine development, enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay |

| 1976 | Baruch S. Blumberg and D. Carleton Gajdusek | New mechanisms for the origin and dissemination of infectious diseases | Idea of persistent infections and slow viruses (spongiform encephalopathies) |

| 1980 | Baruj Benacerraf, Jean Dausset and George D. Snell | Genetically determined structures on the cell surface regulating immunological reactions | Relevance of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) to developing neuroinflammatory disorders, e.g. DR2 in multiple sclerosis |

| 1984 | Niels K. Jerne, Georges J.F. Köhler and César Milstein | Specificity in development and control of the immune system. Principle for production of monoclonal antibodies | Development of monoclonal antibody (mAb) for therapies in neuroinflammatory diseases. mAb for characterizing immune molecules and role in diseases using immunohistochemistry |

| 1987 | Susumu Tonegawa | Genetic principle for generation of antibody diversity | Autoantibodies to peripheral nervous system (PNS) and CNS surface proteins, e.g. ion channels, receptors, myelin, axons |

| 1996 | Peter C. Doherty and Rolf M. Zinkernagel | specificity of the cell mediated immune defence | MHC class I and II restricted immune response applicable to infections and autoimmunity |

| 1997 | Stanley B. Prusiner | Prions: a new biological principle of infection | Modes of action may be applicable to neurodegenerative diseases |

| 2002 | Sydney Brenner, H. Robert Horvitz and John E. Sulston | Genetic regulation of organ development and programmed cell death | Cell death mechanism key to regulating neuronal development, neurodegeneration and control of immune responses |

| 2003 | Paul C. Lauterbur and Sir Peter Mansfield | Magnetic resonance imaging | Imaging neuroinflammatory diseases and response to therapy |

| 2006 | Andrew Z. Fire and Craig C. Mello | RNA interference: gene silencing by double‐stranded RNA | Therapeutic approaches targeting aberrant gene associated with neurological disorders |

| 2007 | Mario R. Capecchi, Martin J. Evans and Oliver Smithies | Principles for introducing gene modifications in mice using embryonic stem cells | The approach allows the study specific gene function and to create animal models for, e.g. neuroinflammatory diseases |

| 2011 | Bruce A. Beutler, Jules A. Hoffmann and Ralph M. Steinman | Discoveries concerning activation of innate immunity (B.A.B., J.A.H.). Role of dendritic cells in adaptive immunity (R.M.S.) | How innate and adaptive immune responses are activated are key to understanding and manipulation of immune responses to control diseases |

| 2012 | John B. Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka | Mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent | Stem cells will facilitate regeneration within the nervous system to replace damaged cells and tissues |

Here, we review the developments in neuroimmunology since its roots in the first descriptions of immunological processes and neurological diseases, as well as the development of technologies and clinical trials for such diseases. Important events are given in major timelines or eras, along with the Nobel Prizes considered relevant by their impact on the field of neuroimmunology. The review also includes a perspective on the future of neuroimmunology that should herald prospective approaches to understanding these diseases, and we address several outstanding questions in the field. The long‐term goal of this rapidly developing field of neuroimmunology is to further the understanding of how immune responses shape the nervous system during development and ageing, how such responses lead to neurological diseases, and ultimately to develop new pharmacological treatments. These aspects are thus the major topics of the International Society of Neuroimmunology meetings (ISNI) (Fig. 1) and the educational topics of the global schools in neuroimmunology.

Historical beginnings

The first descriptions of many neuroinflammatory disorders come from personal notes, early authors and diarists. The earliest report purported to be MS was in an Icelandic woman (in approximately 1200) and Saint Lidwina of Schiedam (1380–1433), while the detailed personal diaries of Sir Augustus d’Esté, born in 1794 (grandson of King George III of England) and the British writer W. N. P. Barbellion (1889–1919) reveal their daily struggle with symptoms of MS 44, 45. Examples of early reports of other neuroinflammatory diseases include Sir Thomas Willis, credited with the first description of myasthenia gravis (MG) in 1672 46 (Fig. 2), as well as in early medical documents and diaries descriptions of encephalitis. Neuroinflammatory disorders were also documented in (albeit) fictional characters in novels such as those by Charles Dickens 47, 48.

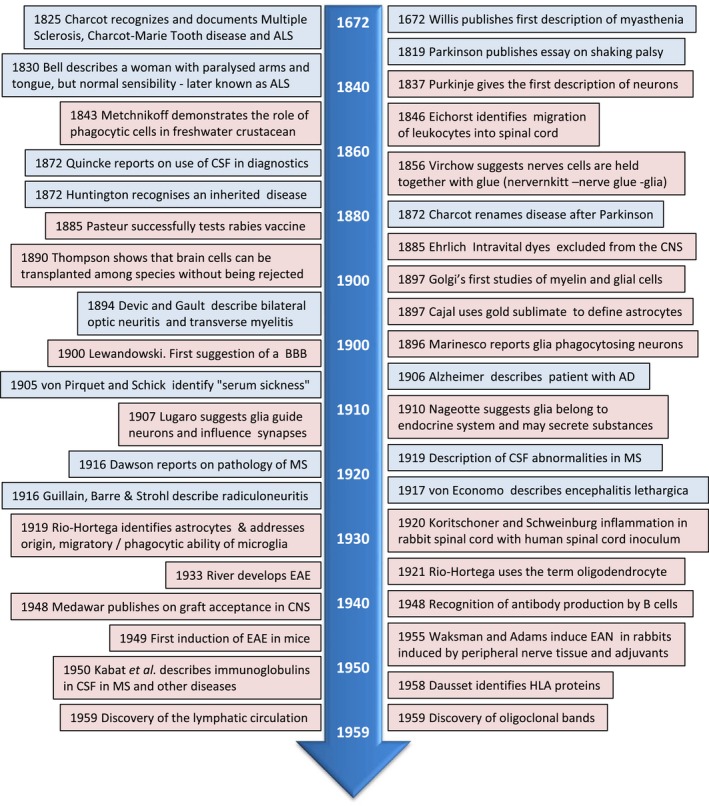

Figure 2.

Neuroimmunology timeline 1672–1959 clinical studies = blue box; research = pink box. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; BBB = blood–brain barrier; CNS = central nervous system; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; EAE = experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; EAN = experimental autoimmune neuritis; HLA = human leucocyte antigen; MS = multiple sclerosis.

Early detailed descriptions of many neurological diseases expanded in the early 1800s (Fig. 2), due in part to Jean‐Martin Charcot (1825–1893), who systematically identified many neurological diseases including Charcot–Marie–Tooth, MS, Parkinson’s disease (PD; only later in 1872 was Parkinson credited for his earlier description, Fig. 2) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), by linking the clinical disease in patients with detailed studies of the anatomy and microscopy of diseased tissues 49. The link between neurology and immunology gained momentum with the refinement of the microscope and development of staining techniques to allow detailed studies of tissue. For example, the identification of different types of glial cells in the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS) was aided by the use of chemicals to enhance the microscopic visibility of nerve cells 50, 51, approaches for which Camillo Golgi and Santiago Ramon y Cajal received the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1906 (Table 2). It was also with these new staining techniques that Alois Alzheimer identified the pathology underlying dementia that later became known as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (1906) 52, and allowed Dawson to perform detailed microscopic examinations of MS (1916) 53 showing inflammation around blood vessels in CNS lesions.

Purkinje is credited for the first descriptions of neurones in 1837 54, and only later did Golgi describe glial cells (1871), although Virchow had introduced the name ‘neuroglia’ and created the concept that nerve cells are held together by ‘glia’ (meaning glue) in 1856 55. Alongside the descriptions of neurological disease, various aspects of immunology were also investigated (Fig. 2). Metchnikoff revealed the rudimentary immune cells in freshwater starfish (1880) 56, and used the term ‘phagocytosis’, which became the basis of his research for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1908 with Paul Ehrlich for discovery of blood leucocytes (Table 2). Later, Rio‐Hortega showed that cells in the brain (microglia) were able to phagocytose (1919) 57. In the same year, Jules Bordet was awarded the Nobel Prize for identifying factors (antibodies) in blood arising after vaccination 58, although it was not until 70 years ago that B cells were found to be important producers of antibodies in 1948 59.

Immunology at the time was focused on the vaccine development for infectious diseases after the published work on the first vaccine for smallpox by British physician Edward Jenner in 1796 60. More relevant for the neuroimmunological field was the discovery of the vaccine for the neurotrophic rabies virus by Louis Pasteur (1885) 61 and the vaccine for polio by Jonas Edward Salk (1953) 62. Importantly, Pasteur used dried virus‐infected rabbit spinal cord for immunization which occasionally induced a post‐vaccine encephalomyelitis in humans. That the disease did not reflect rabies indicated that brain components in the vaccine were antigenic. In the 1940s adjuvants were developed to potentiate vaccines, and several vaccines as well as infections have been linked to neuroinflammatory diseases such as, for example, e.g. MS and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) (Table 1). The serendipitous finding of post‐rabies vaccination encephalitis was later exploited for immunization strategies to deliberately induce experimental autoimmune diseases (Fig. 2). Of relevance to the immune privilege nature of the CNS, in 1890 Gilman Thomson showed that brain cells can be transplanted without being rejected, many years before Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet and Peter B. Medawar’s seminal studies, for which they received the Nobel prize in 1960 (Table 2).

1960–1980

Further to the identification and description of diseases, this era prompted the development of precise criteria for diagnosis of neuroinflammatory diseases, as well as examining the pathological mechanisms underlying disease and testing therapeutic approaches (Fig. 3). Technically, the development of computed tomography scans, positron emission spectroscopy (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allowed the first images of living brain, revolutionizing the diagnosis of neuroinflammatory diseases and allowing non‐invasive monitoring of disease progression as well as response to therapy.

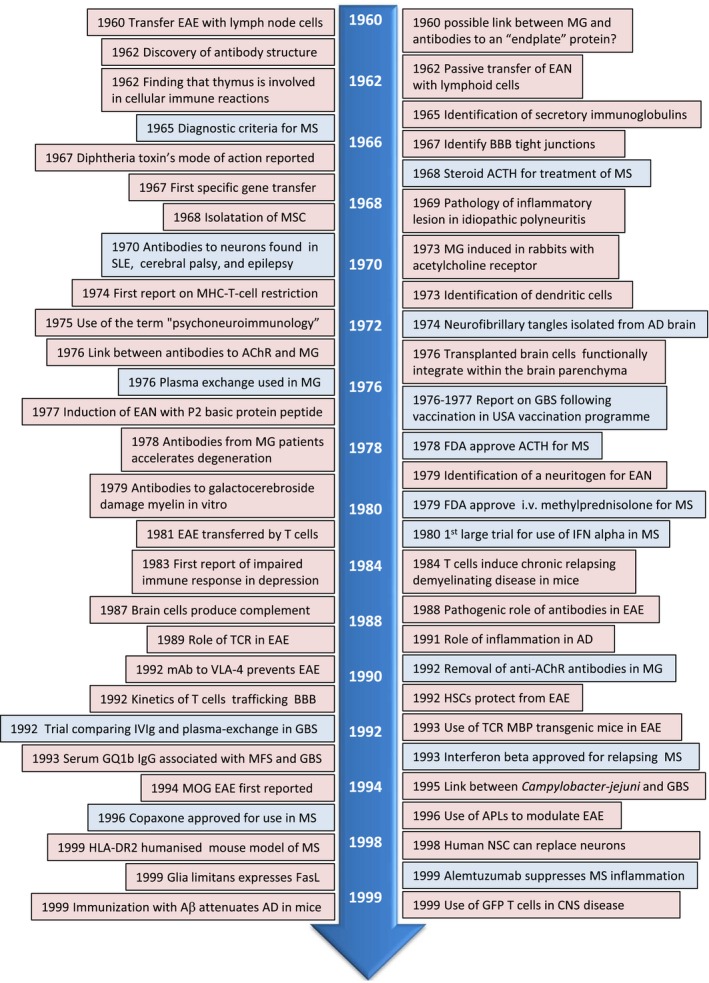

Figure 3.

Neuroimmunology timeline 1960–1999 clinical studies = blue box; research = pink box. Aβ = A beta; AChR = acetyl choline receptor; ACTH = adrenocorticotrophic hormone; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; BBB = blood–brain barrier; CNS = central nervous system; EAE = experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, EAN = experimental autoimmune neuritis; FDA = US Food and Drug Administration; GBS = Guillain–Barré syndrome; GFP = green fluorescent protein; HLA = human leucocyte antigen; HSC = haematopoietic stem cells; IFN = interferon; MG = myasthenia gravis; MHC = major histocompatibility antigen; MOG = myelin associated glycoprotein; MS = multiple sclerosis; MSC = mesenchymal stem cells; NSC = neuronal stem cells; TCR = T cell receptor.

There was a surge in discoveries related to antibodies after the antibody structure was discovered (1959) 63. In this era associations were made linking antibodies to diseases such as MG and other neuroinflammatory diseases 64. For some diseases the target of the antibodies were identified 65, and the impact of pathogenic antibodies shown in vitro 66. A key development in the immunology field was the generation of monoclonal antibodies (mAb) 67. Not only were mAb key to the development of assays such as enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay and other techniques key to linking immune cells to neurological diseases 68, this advancement also allowed development of specific therapeutic approaches in which mAb were designed to block or deplete specific cells of the immune system.

The involvement of immune responses in neurological diseases prompted new approaches to treat disease and development of animal models of human diseases. While adjuvants developed in the 1940s were essential for inducing clinical disease in the case of experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) 69 and experimental autoimmune neuritis (EAN), injection of antibodies to acetylcholine receptor (AchR) and from patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) induced experimental disease in rabbits. The therapy used for antibody‐mediated diseases included plasma exchange 70, while broad immunosuppressive approaches, e.g. adrenocorticotrophic hormone, were implemented for MS [Food and Drug Administration (FDA)‐approved in 1978].

Study of the immune system differentiated between cellular and humoral immunity and recognized T and B cell interactions, as well as the discovery of the first interleukins. Key to further developments in immune‐mediated diseases was Zinkernagel and Doherty’s finding (1974) that elimination of virus‐infected cells killer T cells required not only to recognize the virus but also the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule of the host 71. Around this time the realization grew that cells later named as dendritic cells, due to their morphology, were intricately linked with adaptive immune responses, a notion that would later earn Steinman the Nobel Prize 72. Studies in this era supporting Cajal’s idea, that glia assist neurones, were aided by the development of the electron microscope and electrophysiological studies, although how this impacted on neuroinflammatory disease was as yet unknown.

1981–2000

This era saw major steps in putting neuroimmunology on the map as a new field with the launch of the Journal of Neuroimmunology by Cedric Raine and colleagues (1981), the first PubMed term of neuroimmunology (1981), the initiation of Neuroimmunology Congresses in Stresa, Italy (1982), the foundation of the ISNI (1987) and the launch of the Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuroimmunology in 1988.

If the previous era was dedicated to the role of antibodies in disease for which Tonegawa received the Nobel Prize in 1987 (Table 2) 73, this era was that of T cells in neuroimmunology and the recognition of the importance of innate immunity (Fig. 3). Following Doherty and Zinkernagel’s discovery in 1974, for which they were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1996, major steps were made in identifying the T cell receptor (1983–1987) 74, 75 (Table 2), classification of T cells (1986) 76, the role of MHC peptide complex in triggering T cell responses (1991) 77 and how T cells are regulated (1995) 78 or modified using altered peptide ligands (1998) 79. Models also made use of the emerging field of transgenic mice designed to express human proteins such as human leucocyte antigens (HLA), T cells expressing specific T cell receptors (TCRs), markers such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) to allow tracking of cells or generated to lack specific molecules (knock‐out or deficient mice). Many of the studies examining the pathogenic role of T cells focused on the EAE model of MS (1981–1984) 80, 81, 82 although inflammation was also reported in depression (1983) 83 and neurodegenerative diseases, e.g. AD, which up to that point had been widely assumed to be due to neuronal degeneration. While many studies focused on immune‐mediated damage, studies also revealed the importance of the immune response in shaping neuronal development. For example, while microglia were reported to be crucial for synaptic pruning, new studies from the Shatz laboratory revealed that neuronal expression of MHC class I was key to long‐term structural and synaptic modifications 84.

The focus on pathogenic T cells in EAE models of MS increased and experiments using antibodies to block TCRs were performed 85, 86. Further studies highlighted the importance of other myelin antigens as targets for the demyelinating response and induction of chronic relapsing clinical disease to model the disease course in MS more clearly 87.

Although T cells were at the forefront of many studies, therapeutic approaches targeting pathogenic antibodies such as trials using intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) in GBS, or use of therapeutic mAB to block adhesion molecules on immune cells, revealed the importance of cell trafficking across the BBB 88. Although such approaches were effective in animal models, blocking immune cell entry in the CNS in humans had serious side effects. Other strategies focused on repairing damage in the nervous systems were examined. These strategies included transplanting oligodendrocyte progenitor cells for remyelination 89 and stem cells that, although originally designed to replace damaged cells, they were later recognized to be neuroprotective via the release of growth factors and immune modulatory molecules (i.e. therapeutic plasticity) 90.

This era saw the emergence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the isolation of HTLV‐1‐like retrovirus from tropical spastic paraparesis cases, the link between Campylobacter jejuni infection and GBS and the Nobel Prize to Prusiner for his studies on prions as new infectious particles promoting neurological disease (Table 2). These findings clearly highlighted the role of infectious agents in triggering neuroinflammatory disorders, although it was unclear how the different infections triggered disease. One innovative concept at the time was proposed by Janeway (1989) 91, suggesting that microbes act via receptors on innate immune cells. Only later was this concept validated by the discovery of Toll‐like receptors (TLR) and other innate receptors, as well as dendritic cells (Nobel Prize: Beutler, Hoffman, Steinman 2011). Further revelations were made in 1994, when Matzinger proposed the ‘danger model’ (1994) to include the concept that changes in the host’s tissues due to ‘dangerous’ situations, i.e. trauma or disease, could also activate innate immunity 92.

Another technological leap during this era was the use of genetic engineering that enabled the generation of mice expressing antigen‐specific TCR, such as against the myelin basic protein, and humanized mice expressing certain HLA haplotypes in an attempt to understand how human genes contributed to neuroinflammmatory diseases.

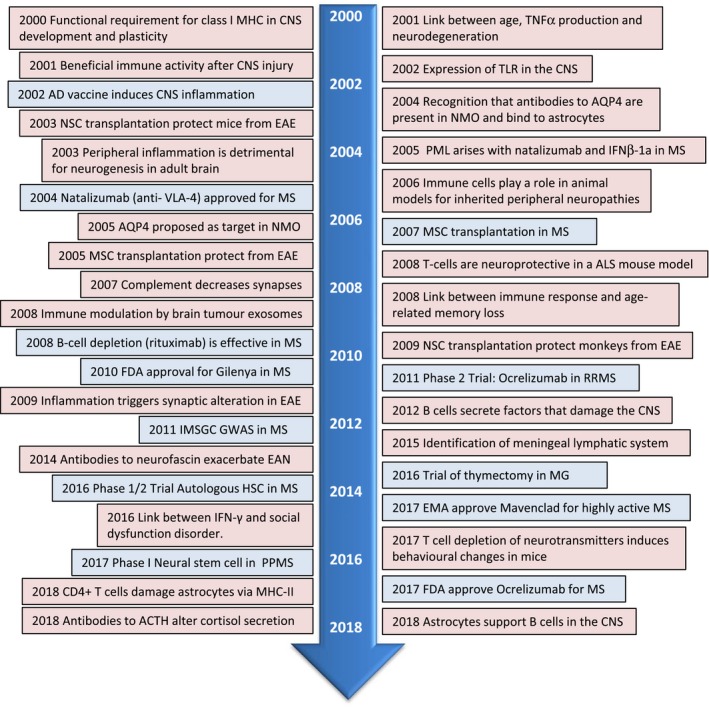

2001–2018

Accumulating evidence during the last two decades shows that immune senescence is associated with late‐onset neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, PD, spinal cerebellar ataxia, ALS and Huntington’s disease, thus broadening the range of diseases falling within the neuroimmunology field (Table 1). Further evidence that the immune response is also key to neuronal development was highlighted by the finding that the complement component C1q is expressed by synapses of postnatal but not adult neurones 93 (Fig. 4). Studies in this era have also expanded ideas of how microbes, such as the newly emerging Zika virus, the re‐emergence of Ebola and the gut microbiome, influence susceptibility to neuroinflammatory disease. In line with this, clinical trials have highlighted the need to develop more specific approaches in neuroimmune diseases other than broad immunosuppression or blocking cells from entering into the CNS, in order to avoid the emergence of opportunistic infections. Thus, specific approaches such as cell depletion therapies (e.g. of B cells in MS), tolerance‐inducing strategies and the use of stem cells have been a major focus in MS, while gene therapy approaches have been initiated in an attempt to correct genetic mutations in ALS 94 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Neuroimmunology timeline 2001–2018. Clinical studies = blue box; research = pink box. ACTH = adrenocorticotrophic hormone; ALS = amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; AQP4 = aquaporin 4; CNS = central nervous system; EAE = experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; EAN = experimental autoimmune neuritis; EMA = European medical agency; FDA = US Food and Drug Administration; GWAS = genomewide association study; IFN = interferon; IMSGC = International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium (IMSGC); MHC = major histocompatibility antigen; MG = myasthenia gravis; MS = multiple sclerosis; MSC = mesenchymal stem cells; NMO = neuromyelitis optica; NSC ; neuronal stem cells; PML = progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy; PPMS = primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RRMS = relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis; VLA‐4 = integrin α4β1 (very late antigen‐4); TLR = Toll‐like receptors; TNF = tumour necrosis factor.

Probing neuroinflammatory diseases has been aided with improved higher‐resolution MRI, single photon emission computed tomography and PET ligands 95, 96, and optical coherence tomography to visualize the progression of disease in patients and for some modes the contribution of inflammation. Similarly, in‐vivo optical imaging, for example of GFP‐labelled T cells, glia or transplanted human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), in experimental models has greatly influenced our knowledge of the cross‐talk between the immune and nervous systems 97.

Although mainly limited to in‐vitro and animal studies, genetic modification has proved to be an indispensable tool to study gene function in normal development and disease and has yielded several Nobel Prizes in this area (2006, Fire and Mello; 2007, Capecchi, Evans, Smithies). Breakthroughs in this era include the generation of human iPSCs for which Gurdon and Yamanaka received the Nobel Prize in 2012; gene‐targeting approaches and genome‐editing tools, the most effective for interrogation of neuroimmune disease being the CRISPR/Cas9 system (derived from clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) originating from early discoveries in bacteria 98. While yet to prove applicable to human disorders, such gene editing has allowed genetic manipulation of iPSC from humans, ALS models and elimination of viral infections by targeting viral genomes.

Future perspectives

While current therapies aim to modulate neuroinflammation arising during the disease, future approaches should aim at disease prevention. For some diseases, the aetiological agents are known, and thus vaccination strategies are key for disease prevention. In other cases, the specific genes or environmental agents triggering disease require clarification. Prophylactic approaches for genetic disorders could exploit genetic modification during development, while cell therapy strategies may aid regeneration of the damaged nervous system. Exploitation of infections agents may also be beneficial, as demonstrated by the recent clinical trial using a non‐pathogenic poliovirus for treating glioblastomas 99.

For disease prevention, rapid and specific diagnosis as well as adequate ways to monitor the disease course and response to therapy are crucial. Thus, advancements in biomarker research will be key to faster diagnosis and more efficient monitoring in clinical trials, speeding up drug development and reducing costs. Biomarkers of neuroimmunological diseases may include markers of BBB disruption, demyelination, oxidative stress and excitotoxicity, axonal/neuronal damage, gliosis, remyelination and repair, but should also focus on markers of altered immune function such as cytokines, chemokines, antibodies, adhesion molecules, antigen presentation and changes in cellular subpopulations 100. Ideally, detection and collection of new biomarkers will be minimally invasive, specific for the disease and reflect response to therapy Additionally, well‐characterized tissue biobanks will be crucial to these advancements in biomarkers.

Another important aspect of future neuroimmunology research and developments will be in disease modelling. The highly effective CRISPR/cas9 system will allow precision engineering of the genome, and has the potential to speed up the generation of transgenic animal models, generating single‐gene mutations in adult animals. Model systems making use of iPSCs from patients will also allow better translation of fundamental research data to the clinic. Further advances in CRISPR/cas9 or similar systems to increase transgene efficiency or to regulate gene expression using inducible expression systems will allow genes to be regulated once gene editing is completed. Such approaches will herald better treatments in the form of personalized medicine, gene editing (taking into account the ethical issues) and improved clinical trial design.

The increase in data generated by next‐generation sequencing is expected to aid identification of genetic variants in neuroimmunological diseases. Such data are already contributing to designing algorithms, development of pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine. These approaches will be fundamental in reducing risks in drug development by avoiding adverse drug reactions, and minimizing cost by limiting drug administration solely to those patients who will benefit 101. While drug discovery is increasingly costly and prolonged, artificial intelligence (AI) may be key to reversing this trend. AI will use previously collected data and molecular dynamic predictions to reduce the number of compounds to be screened, repurpose compounds, predict interactions between compounds and their target and refine clinical trial populations 102. Advancements in targeted drug delivery will also reduce side‐effect profiles of compounds and aid in those compounds that will readily cross the BBB 103. Both Big Pharma and academia have the potential to increase drug discovery efficiency by embracing AI, pharmacogenomics, personalized medicine and targeted drug delivery to provide future treatments of neuroimmunological diseases.

Conclusions

The field of neuroimmunology has evolved from early studies recognizing that immune responses are present in the CNS and PNS during disease, to sophisticated approaches for manipulation of the immune system. The list of neuroimmune diseases has expanded from the prototypical cases of MS, GBS and MG to incorporate diseases considered to be purely neurological such as AD, PD, ALS as well as behavioural and mood disorders. Neuroimmunology has evolved to encompassed less disease‐orientated fields by addressing how the immune system impacts upon the developing nervous systems during pregnancy, how neural stem cells play an immune regulatory role, the contribution of immune‐senescence to ageing, how microbiota influence the immune system, and how this impacts upon development and susceptibility to neurological diseases.

Understanding the delicate balance between the beneficial and pathological effects of the immune system with neuronal development and diseases has already allowed the development of rational approaches for treating neuroimmune disorders. Further advances are expected to address the following points.

How pathogenic (auto)antibodies arise and how they contribute to immune‐mediated neurological disorders

While the source of pathogenic antibodies in paraneoplastic neurological syndrome (PNS) are well described, a significant number of neurological diseases in which pathogenic antibodies directed to neuronal structures are not related to cancer. Uncovering how these antibodies arise, how they enter the nervous systems and approaches to inhibit antibody formation will be key to developing effective therapeutic approaches.

The role of memory B cells in autoimmune diseases

For several autoimmune disorders, e.g. MS, rheumatoid arthritis and Graves’ disease, among others, an association has been made between Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and development of disease. The recent awareness that effective therapies target memory B cells makes the hypothesis that EBV triggers autoreactive B cells and/or antibodies is very compelling. Exactly how EBV triggers autoimmune neurological diseases will be an important step in understanding neuroimmunological diseases such as MS.

Inflammaging and neurological diseases

The term ‘inflammaging’ has been used to describe the chronic, low‐grade inflammation associated with ageing. Senescence in the immune and nervous systems covers a multitude of factors, including lowered response to vaccination, decline in effective autophagy and increased susceptibility to cancer and autoimmune diseases. Why such changes occur will be aided by studying healthy aged cohorts of different backgrounds and races and highlight how environmental factors such as diet, gut microbiota or genes and lifestyle contribute to the immune imbalance associated with ‘inflammaging’. A key question will thus be: ‘Can we manipulate the immune response to combat the effects of ageing?’.

Neuroimmunology of pregnancy and development

Maternal stress or infections during pregnancy have been linked to impaired cognitive development and psychiatric disorders in the offspring. The recent emergence of Zika virus has underscored not only how the brain may be shaped by infections during development, but that such infections may predispose to autoimmune diseases later in life. A future challenge will thus be to understand how maternal immune factors, including immune cells and cytokines, influence brain development in utero and modulate the beneficial factors to enhance brain development to prevent and limit the detrimental effects of the immune system that may contribute to behavioural and mood disorders.

Human stem cell technology and personalized medicine

The advances in reprogramming somatic cells into iPSCs has allowed the culture of patient‐specific stem cells, e.g. neuronal stem cells (NSC), to study the disease specific pathways. This technology will allow the development of human in‐vitro models to study disease and patient‐specific pathways. More importantly, these models should also allow approaches to modulate disease‐specific factors aiding personalized medicine. For some neuroimmunological diseases the use of NSC has already proved effective in experimental settings to not only repair the nervous system but examine an unexpected trait by which NSC modulate immune responses. While in its infancy, gene‐editing approaches are expected to develop to the point that genetic neurological diseases may be treatable and modulate the immune and nervous systems to combat neuroimmunological disease, and in the meantime allow standardization of iPSC cells.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgements

This review was written in celebration of the 60 years’ anniversary of the foundation of the British Society of Immunology, and following the 13th ISNI meeting in 2018 in Brisbane. We thank our colleagues in the neuroimmunology field who have contributed to this review in terms of discussions and their invaluable insight into neuroimmune diseases. Specifically, we thank Dr Hans van Noort and Dr Gareth Pryce for their input with critical feedback on the paper. To the neuroimmunologists whom we have not mentioned due to lack of space, we warmly encourage them and readers to make suggestions of omissions.

OTHER ARTICLES PUBLISHED IN THIS REVIEW SERIES

Neuroimmune interactions: how the nervous and immune systems influence each other. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2019, 197: 276–277.

The immune system and psychiatric disease: a basic science perspective. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2019, 197: 294–307

Depressive symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease: an extraintestinal manifestation of inflammation? Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2019, 197: 308–318.

From early adversities to immune activation in psychiatric disorders: the role of the sympathetic nervous system. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2019, 197: 319–328.

References

- 1. Kim S, Kim H, Yim YS et al Maternal gut bacteria promote neurodevelopmental abnormalities in mouse offspring. Nature 2017; 549:528–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peferoen L, Kipp M, van der Valk P, van Noort JM, Amor S. Oligodendrocyte‐microglia cross‐talk in the central nervous system. Immunology 2014; 141:302–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perry VH, Cunningham C, Holmes C. Systemic infections and inflammation affect chronic neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Immunol 2007; 7:161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schaafsma W, Basterra LB, Jacobs S et al Maternal inflammation induces immune activation of fetal microglia and leads to disrupted microglia immune responses, behavior, and learning performance in adulthood. Neurobiol Dis 2017; 106:291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi GB, Yim YS, Wong H et al The maternal interleukin‐17a pathway in mice promotes autism‐like phenotypes in offspring. Science 2016; 351:933–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pohl D, Alper G, Van Haren K et al Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: updates on an inflammatory CNS syndrome. Neurology 2016; 87:S38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lu C‐H, Allen K, Oei F et al Systemic inflammatory response and neuromuscular involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2016; 3:e244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mantovani S, Garbelli S, Pasini A et al Immune system alterations in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients suggest an ongoing neuroinflammatory process. J Neuroimmunol 2009; 210:73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Malaspina A, Puentes F, Amor S. Disease origin and progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an immunology perspective. Int Immunol 2014; 27:117–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Eldik LJ, Carrillo MC, Cole PE et al The roles of inflammation and immune mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2016; 2:99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bryson KJ, Lynch MA. Linking T cells to Alzheimer’s disease: from neurodegeneration to neurorepair. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2016; 26:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Honnorat J, Plazat L. Autoimmune encephalitis and psychiatric disorders. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2018; 174:228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baizabal‐Carvallo JF, Jankovic J. Distinguishing features of psychogenic (functional) versus organic hemifacial spasm. J Neurol 2017; 264:359–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Montoya JG, Holmes TH, Anderson JN et al Cytokine signature associated with disease severity in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017:201710519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bougea A, Spantideas N. Vasculitis in the central nervous system. The immunology of cardiovascular homeostasis and pathology. New York, NY: Springer; 2017, 173–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Doolin K, Farrell C, Tozzi L, Harkin A, Frodl T, O’Keane V. Diurnal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis measures and inflammatory marker correlates in major depressive disorder. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18:2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hughes MM, Connor TJ, Harkin A. Stress‐related immune markers in depression: implications for treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2016; 19:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Terrone G, Salamone A, Vezzani A. Inflammation and Epilepsy: preclinical findings and potential clinical translation. Curr Pharm Des 2017; 23:5569–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Noe FM, Polascheck N, Frigerio F et al Pharmacological blockade of IL‐1beta/IL‐1 receptor type 1 axis during epileptogenesis provides neuroprotection in two rat models of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis 2013; 59:183–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goodfellow JA, Willison HJ. Guillain–Barré syndrome: a century of progress. Nat Rev Neurol 2016; 12:723–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, Machinami R, Kanazawa I. Serum anti‐GQ1b IgG antibody is associated with ophthalmoplegia in Miller Fisher syndrome and Guillain–Barré syndrome: clinical and immunohistochemical studies. Neurology 1993; 43:1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ellrichmann G, Reick C, Saft C, Linker RA. The role of the immune system in Huntington’s disease. Clin Dev Immunol 2013; 2013:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cosby SL, Galbraith S, Healy D. CNS infections. Neuroinflamm CNS Disord 2014; 151–84. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eichler F, Van Haren K. Immune response in leukodystrophies. Pediatr Neurol 2007; 37:235–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Köhler W, Curiel J, Vanderver A. Adulthood leukodystrophies. Nat Rev Neurol 2018; 14:94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Forsthuber TG, Cimbora DM, Ratchford JN, Katz E, Stüve O. B cell‐based therapies in CNS autoimmunity: differentiating CD19 and CD20 as therapeutic targets. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2018; 11:1756286418761697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shiono H, Roxanis I, Zhang W et al Scenarios for autoimmunization of T and B cells in myasthenia gravis. Ann NY Acad Sci 2003; 998:237–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buckley C, Vincent A. Autoimmune channelopathies. Nat Rev Neurol 2005; 1:22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Matsuya N, Komori M, Nomura K et al Increased T‐cell immunity against aquaporin‐4 and proteolipid protein in neuromyelitis optica. Int Immunol 2011; 23:565–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hadjivassiliou M. Other autoimmune disorders: systemic lupus erythematosus, primary Sjögren’s syndrome, gluten‐related neurological dysfunction and paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. Neuroinflamm CNS Disord 2014; 235–60. [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Virgilio A, Greco A, Fabbrini G et al Parkinson’s disease: autoimmunity and neuroinflammation. Autoimmun Rev 2016; 15:1005–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Emsley HC, Smith CJ, Tyrrell PJ, Hopkins SJ. Inflammation in acute ischemic stroke and its relevance to stroke critical care. Neurocrit Care 2008; 9:125–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Popovich PG, Popovich P. Neuroimmunology of traumatic spinal cord injury: a brief history and overview. Exp Neurol 2014:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hong S, Banks WA. Role of the immune system in HIV‐associated neuroinflammation and neurocognitive implications. Brain Behav Immun 2015; 45:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Griffin DE. Arboviruses and the central nervous system. Springer Semin Immunopathol 1995; 17:121–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amor S, Scallan MF, Morris MM, Dyson H, Fazakerley JK. Role of immune responses in protection and pathogenesis during Semliki Forest virus encephalitis. J Gen Virol 1996; 77:281–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ashhurst TM, van Vreden C, Munoz‐Erazo L et al Antiviral macrophage responses in flavivirus encephalitis. Ind J Med Res 2013; 138:632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hooper DC, Roy A, Barkhouse DA, Li J, Kean RB. Rabies virus clearance from the central nervous system. Adv Virus Res 2011; 79:55–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shives KD, Tyler KL, Beckham JD. Molecular mechanisms of neuroinflammation and injury during acute viral encephalitis. J Neuroimmunol 2017; 308:102–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alpert G, Fleisher GR. Complications of infection with Epstein–Barr virus during childhood: a study of children admitted to the hospital. Pediatr Infect Dis 1984; 3:304–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Connelly KP, DeWitt LD. Neurologic complications of infectious mononucleosis. Pediatr Neurol 1994; 10:181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dhib‐Jalbut S, McFarland H, Mingioli E, Sever J, McFarlin D. Humoral and cellular immune responses to matrix protein of measles virus in subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J Virol 1988; 62:2483–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Louveau A, Harris TH, Kipnis J. Revisiting the mechanisms of CNS immune privilege. Trends Immunol 2015; 36:569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Landtblom AM, Fazio P, Fredrikson S, Granieri E. The first case history of multiple sclerosis: Augustus d’Este (1794–1848). Neurol Sci 2010; 31:29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Heys R. The journal of a disappointed man. BMJ 2008; 336:1195. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Simpson JA. Myasthenia gravis: a new hypothesis. Scott Med J 1960; 5:419–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Petzold A. Optic neuritis: another Dickensian diagnosis. Neuro‐Ophthalmology 2013; 37:247–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brain R. Dickensian diagnoses. BMJ 1955; 2:1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Waraich M, Shah S. The life and work of Jean‐Martin Charcot (1825–1893): ‘The Napoleon of Neuroses’. J Intens Care Soc 2018; 19:48–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Golgi C. Sulla fina anatomia degli organi centrali del sistema nervosa [On the fine structure of the central features of the nervous system]: S. Calderini, 1885. Edinburgh: Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 1886. [Google Scholar]

- 51. y Cajal SR. The Croonian lecture. La fine structure des centres nerveux [The fine structure of the central nervous system] . Proc R Soc Lond 1894; 55:444–68. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alzheimer A. Über einen eigenartigen schweren Erkrankungsprozeβ der Hirnrincle [A characteristic disease of the cerebral cortex]. Neurol Central 1906; 25:1134. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dawson JW. The histology of disseminated sclerosis. Edinb Med J 1916; 17:311. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Purkinje JE. Neueste Untersuchungen aus der Nerven und Hirn Anatomie [Recent investigations from the nerves and brain anatomy] . Bericht über die Versammlung deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte in Prag im September [Report on the assembly of German naturalists and physicians in Prague in September] 1837; 1883:177–80. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Virchow R. Cellular‐pathologie . Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med 1855; 8:3–39. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Metchnikoff E. Uber die intracellulare Verdauung bei Coelenteraten [About intracellular digestion of coelenterates]. Zool Anz 1880; 3:261–3. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Del Rio‐Hortega P. El tercer elemento de los centros nerviosos. I. La microglia en estado nor‐mal. II. Intervencion de la microglia en los procesos patologicos. III. Naturaleza probable de la microglia [The third element of the nerve centers. I. Microglia in normal condition. II. Intervention of the microglia in pathological processes. III. Probable nature of microglia]. Boll Socieded Esp Biol 1919; 9:69–120. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schmalstieg FC Jr, Goldman AS. Jules Bordet (1870–1961): a bridge between early and modern immunology. J Med Biogr 2009; 17:217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fagraeus A. Antibody production in relation to the development of plasma cells. In vivo and in vitro experiments. Acta Med Scand 1948; 130. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jenner E. An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolae vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of the cow pox. Springfield, MA: Samuel Cooley, 1800. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pasteur L. Methode pour prevenir la rage apres morsure [Method for preventing rabies after bite]. C R Acad Sci 1885; 101:765. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Salk JE. Studies in human subjects on active immunization against poliomyelitis. I. A preliminary report of experiments in progress. J Am Med Assoc 1953; 151:1081–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Porter R. The hydrolysis of rabbit γ‐globulin and antibodies with crystalline papain. Biochem J 1959; 73:119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Diederichsen H, Pyndt IC. Antibodies against neurons in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy. Brain 1970; 93:407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lindstrom JM, Seybold ME, Lennon VA, Whittingham S, Duane DD. Antibody to acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and diagnostic value. Neurology 1976; 26:1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saida T, Saida K, Dorfman SH et al Experimental allergic neuritis induced by sensitization with galactocerebroside. Science 1979; 204:1103–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Köhler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 1975; 256:495–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Engvall E, Perlmann P. Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Immunochemistry 1971; 8:871–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rivers TM, Schwentker FF. Encephalomyelitis accompanied by myelin destruction experimentally produced in monkeys. J Exp Med 1935; 61:689–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pinching A, Peters D, Davis JN. Remission of myasthenia gravis following plasma‐exchange. Lancet 1976; 308:1373–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zinkernagel R, Doherty P. Restriction of in vitro T cell‐mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic choriomeningitis within a syngeneic or semiallogeneic system. Nature 1974; 248;701–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Steinman RM, Cohn ZA. Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. J Exp Med 1973; 137:1142–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature 1983; 302:575–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Meuer SC, Fitzgerald KA, Hussey RE, Hodgdon JC, Schlossman SF, Reinherz EL. Clonotypic structures involved in antigen‐specific human T cell function. Relationship to the T3 molecular complex. J Exp Med 1983; 157:705–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Marrack P, Kappler J. The T cell receptor. Science 1987; 238.4830:1073–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol (Balt) 1986; 136:2348–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sadegh‐Nasseri S, Germain RN. A role for peptide in determining MHC class II structure. Nature 1991; 353:167–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self‐tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL‐2 receptor alpha‐chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self‐tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol 1995; 155:1151–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Santambrogio L, Lees MB, Sobel RA. Altered peptide ligand modulation of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: immune responses within the CNS. J Neuroimmunol 1998; 81:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ben‐Nun A, Cohen IR. Vaccination against autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE): attenuated autoimmune T lymphocytes confer resistance to induction of active EAE but not to EAE mediated by the intact T lymphocyte line. Eur J Immunol 1981; 11:949–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mokhtarian F, McFarlin D, Raine C. Adoptive transfer of myelin basic protein‐sensitized T cells produces chronic relapsing demyelinating disease in mice. Nature 1984; 309:356–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Linington C, Izumo S, Suzuki M, Uyemura K, Meyermann R, Wekerle H. A permanent rat T cell line that mediates experimental allergic neuritis in the Lewis rat in vivo . J Immunol 1984; 133:1946–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kronfol Z, Silva J Jr, Greden J, Dembinski S, Gardner R, Carroll B. Impaired lymphocyte function in depressive illness. Life Sci 1983; 33:241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Huh GS, Boulanger LM, Du H, Riquelme PA, Brotz TM, Shatz CJ. Functional requirement for class I MHC in CNS development and plasticity. Science 2000; 290:2155–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Vandenbark AA, Hashim G, Offner H. Immunization with a synthetic T‐cell receptor V‐region peptide protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nature 1989; 341:541–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lider O, Reshef T, Beraud E, Ben‐Nun A, Cohen IR. Anti‐idiotypic network induced by T cell vaccination against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science 1988; 239:181–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Amor S, Groome N, Linington C et al Identification of epitopes of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein for the induction of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in SJL and Biozzi AB/H mice. J Immunol 1994; 153:4349–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yednock TA, Cannon C, Fritz LC, Sanchez‐Madrid F, Steinman L, Karin N. Prevention of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by antibodies against α4βl integrin. Nature 1992; 356:63–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Groves AK, Barnett SC, Franklin RJ et al Repair of demyelinated lesions by transplantation of purified O‐2A progenitor cells. Nature 1993; 362:453–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Pluchino S, Quattrini A, Brambilla E et al Injection of adult neurospheres induces recovery in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis. Nature 2003; 422:688–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Janeway CA. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 1989; 54:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Matzinger P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol 1994; 12:991–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE et al The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell 2007; 131:1164–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Miller TM, Pestronk A, David W et al An antisense oligonucleotide against SOD1 delivered intrathecally for patients with SOD1 familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase 1, randomised, first‐in‐man study. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12:435–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Tommasin S, Giannì C, De Giglio L, Pantano P. Neuroimaging techniques to assess inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Neuroscience 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Shimizu S, Hirose D, Hatanaka H et al Role of neuroimaging as a biomarker for neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neurol 2018; 9:265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Akassoglou K, Merlini M, Rafalski VA et al In vivo imaging of CNS injury and disease. J Neurosci 2017; 37:10808–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Jansen R, Embden JD, Gaastra W et al Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol 2002; 43:1565–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Desjardins A, Gromeier M, Herndon JE et al Recurrent glioblastoma treated with recombinant poliovirus. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:150–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Bielekova B, Martin R. Development of biomarkers in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2004; 127:1463–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Bartfai T, Lees GV. The future of drug discovery: who decides which diseases to treat? Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Zhong F, Xing J, Li X, Liu X, Fu Z, Xiong Z. Artificial intelligence in drug design. Sci China Life Sci 2018; 61:1191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kabanov AV, Batrakova EV. Polymer nanomaterials for drug delivery across the blood brain barrier In: Ikezu T, Gendelman H, eds. Neuroimmune pharmacology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2017,847–68. [Google Scholar]