Abstract

Three fluorescent organic compounds—furocoumarin (FC), dansyl aniline (DA), and 7-hydroxycoumarin-3-carboxylic acid (CC)—are mixed to produce almost pure white light emission (WLE). This novel mixture is immobilised in silica aerogel and applied as a coating to a UV LED to demonstrate its applicability as a low-cost, organic coating for WLE via simultaneous emission. In ethanol solution and when immobilised in silica aerogel, the mixture exhibits a Commission Internationale d’Eclairage (CIE) chromaticity index of (0.27, 0.33). It was observed that a broadband and simultaneous emission involving coumarin carboxylic acid, furocoumarin and dansyl aniline played a vital role in obtaining a CIE index close to that of pure white light.

Subject terms: Organic chemistry, Photochemistry, Green chemistry, Organic LEDs

Introduction

As display and lighting technology develops, efficient and environmentally friendly methods of producing coloured and white light are in increasing demand. Inorganic luminescence has long been established as a means to produce light with a range of colour profiles. However, most inorganic light-emitters are not environmentally friendly due to their high energy consumption and the process usually involving, liberating, or containing scarce metals or highly toxic chemicals like arsenic and cyanides. Organic fluorescent materials show excellent potential as a low-cost, green and sustainable alternative1,2. The most common application of organic fluorescence is for lighting purposes and there is much research surrounding other applications such as fluorescent labelling for bio-imaging3–7 and chemosensors8–13. Organic fluorescent materials have contributed significant advancements in the field of artificial lighting14. In particular, light emitting devices based on organic materials such as organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) and liquid crystal displays (LCDs) have received extensive attention in recent years15,16. Recent commercialisation of OLED technologies has further increased the demand for successful developments of organic white-light emitting systems17,18.

Several photo-physical principles have been used to achieve white light emission14,19, these include inter- and intramolecular charge transfer20, Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET)2,21–23, excited state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT)24,25, hydrogen bonding mediated J-aggregation26 and the mixing of monomer and excimer fluorescence27. Multi-component white light emission (WLE) comprises a mixture of different molecules that allow the colour temperature to be tuned by simply adjusting the composition, compared to using a single molecule28. Not surprisingly, there is significant recent interest for generation of mixed emitter WLE. Such systems comprise of inorganic, organic and hybrid systems including polymers29, metal-organic frameworks30,31, metal complexes32 and lanthanide doped systems33. Several examples of strategies employing mixtures of organic fluorophores have been reported, including a mixture of three emitting dyes covering the RGB region34, donor-acceptor conjugated pairs22 and self-assembly based compounds35–39. For instance, Wang et al. reported that micelle isolation can be used to inhibit FRET between fluorophores, thereby resulting in simultaneous emission of RGB dyes to produce WLE40. However, the WLE intensity is low due to the amount of fluorescent dyes encapsulated as the micellar core is restricted. Further to this, Wang and co-workers developed a new method to enhance the intensity of WLE by controlling FRET and micellar nanostructures such that the RGB intensities could be increased to produce simultaneous emission41. Others have mixed a range of oligomers that rely on intramolecular fluorescence energy transfer processes like FRET to produce tuneable WLE38,42,43. Our novel approach is to target a mixture of simple organic compounds that share a similar range of excitation wavelengths in the UVA region (340–375 nm) yet emit at different wavelengths in the visible range (400–700 nm). We hypothesise that a mixture of three such components should emit white light and this can be combined with a suitable, commercially available UV LED.

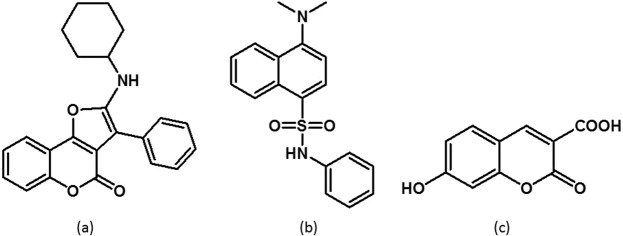

Three compounds were identified for this strategy: furocoumarin (FC), dansyl aniline (DA), and 7-hydroxycoumarin-3-carboxylic acid (CC) as shown in Fig. 1, respectively. These compounds yield distinct emission colours yet are all excited in the UVA region (340 to 375 nm). 7-hydroxycoumarin-3-carboxylic acid is commercially available and was used as purchased. The synthesis of furo[3,2-c]coumarin was reported by Nair and co-workers and involves a [4 + 1] cycloaddition with in-situ generated heterocyclic coumarin methides and isocyanides44. The synthesis of dansyl aniline was adapted from a procedure reported by Xiao et al. (see Materials and Methods)45.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of (a) FC, (b) DA and (c) CC.

Results and Discussion

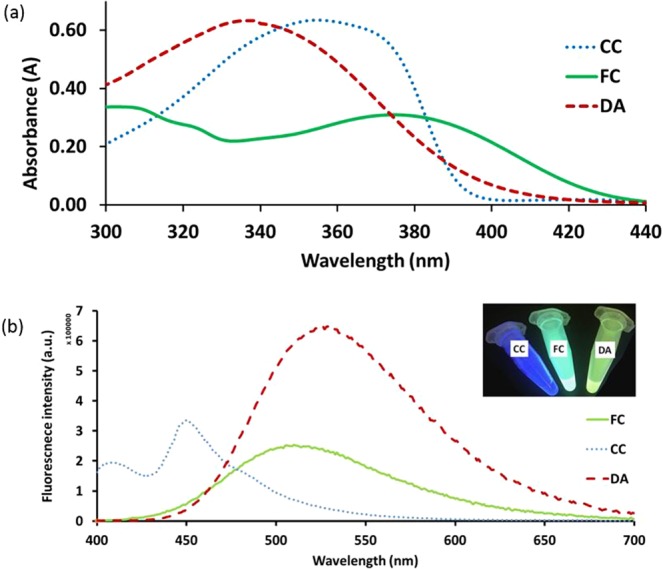

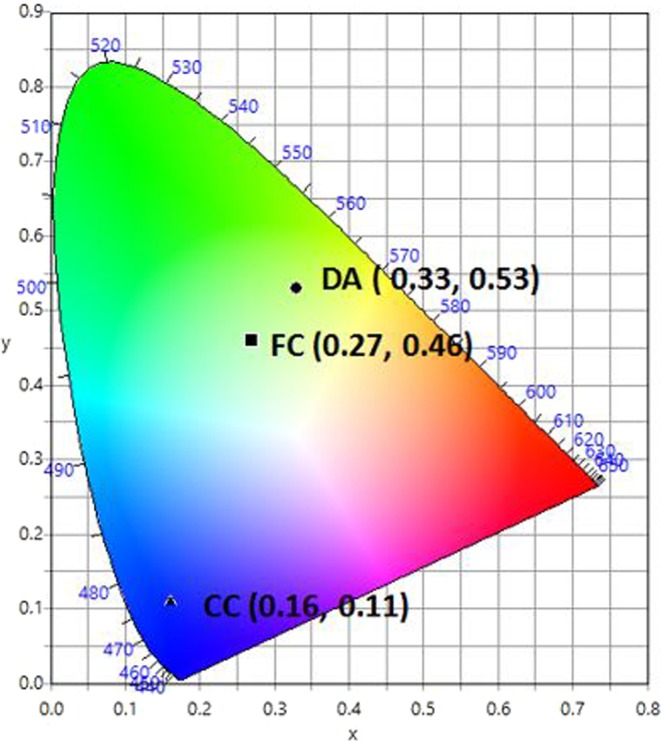

Each of the three fluorescent organic compounds was prepared in requisite proportions (CC = 2.2 × 10−3 M, FC = 1.6 × 10−3 M and DA = 1.6 × 10−3 M) in ethanol and subjected to UV-Vis absorption and fluorescence spectral studies. UV-Vis absorption and fluorescence spectra for all of the fluorescents are shown in Fig. 2a,b, respectively. Each of the fluorescents has a broad characteristic absorption band of around 300–420 nm with varying maxima; 339 nm for DA, 355 nm for CC, and 375 nm for FC. Fluorescence emission maxima occur at 450 nm, 512 nm, and 530 nm for DA, CC, and FC, respectively. Under UV light excitation at 390 nm, CC, FC, and DA show blue, cyan and yellow emission, respectively (inset photograph, Fig. 2b). The CIE chromaticity coordinate for CC appears in the blue-violet region (0.16, 0.11); the coordinate for FC appears in the cyan region (0.27, 0.46); for DA it appears in the green-yellow region (0.33, 0.53) of the CIE diagram (Fig. 3). It is observed that the points for CC, FC and DA appear on the opposite side of the white region in the CIE diagram. From this observation it was hypothesised that it should be possible to obtain WLE by mixing the three fluorescent compounds.

Figure 2.

(a) Absorption spectra for each of the compounds (CC = 2.2 × 10−5 M, FC = 1.6 × 10−5 M and DA = 1.6 × 10−5 M) in ethanol. (b) Fluorescence spectra for each of the compounds (CC = 2.2 × 10−3 M, FC = 1.6 × 10−3 M and DA = 1.6 × 10−3 M) in ethanol. Inset: Photograph taken under UV light (390 nm) for each of the compounds (CC, FC and DA) in ethanol.

Figure 3.

CIE-1931 diagram. Chromaticity plot for colour coordinates of CC (▲), FC (■) and DA (●).

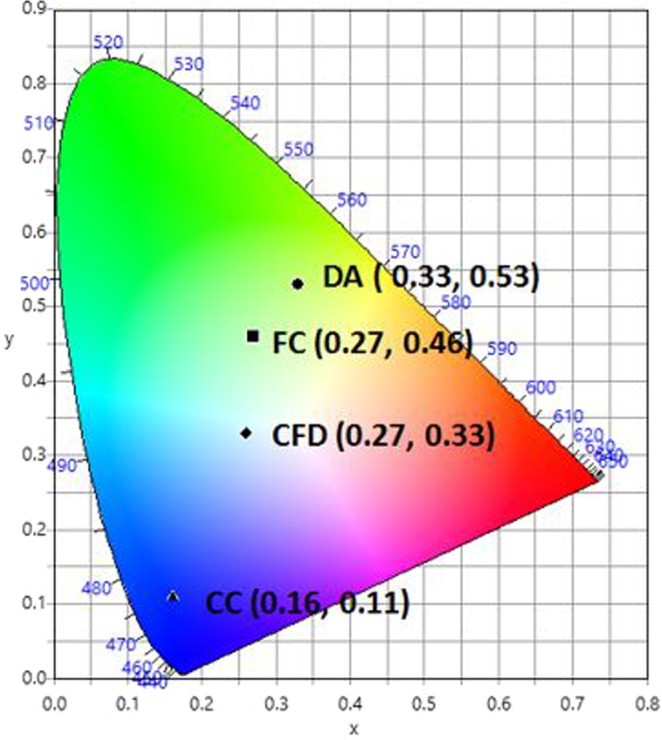

Accordingly, a series of solutions were prepared by varying the ratio of DA with a fixed ratio of CC and FC at 1.375:1 (Supplementary Table S1). Solutions were prepared containing varying ratios of CC:FC:DA (1.375:1:3, 1.375:1:4, 1.375:1:5, 1.375:1:6 and 1.375:1:7) and were analysed by UV-Vis absorption and fluorescence spectral studies as shown at Figs S1, S2a–c and S3. Based on the UV-Vis spectra, all the ratios show similar excitation wavelength, within the range of 350 to 355 nm. The mixture of the fluorescent solution was excited at various wavelengths (340, 350, 360, 370, 375, 380,390, 400 and 404 nm). Further increases in the concentration ratio up to 1.375:1:8 and 1.375:1:9 were also trialled but led to an increasingly yellow coloured emission profile, therefore no further fluorescence analysis was conducted at these increased ratios as it was deemed to be beyond the scope of the present research objective (to produce WLE). Each of the fluorescence spectra shows almost similar bands of emission and fluorescence intensity except at 390 nm, 400 nm and 404 nm. From these, 390 nm exhibits high fluorescence intensity with a broadband emission profile, producing almost pure white light emission. By varying the excitation wavelength it is expected that, for a mixture of different fluorophores, the emission profile should vary46. Figure 4 shows the colour coordinates for these solutions in the CIE diagram. It is seen that the point CFD (0.27, 0.33), corresponding to the composition concentration of CC = 2.2 × 10−3 M, FC = 1.6 × 10−3 M and DA = 1.6 × 10−3 M, with ratio of 1.375:1:7; CC:FC:DA, is extremely close to that of pure white light (0.33, 0.33).

Figure 4.

CIE-1931 diagram. Chromaticity plot for colour coordinates of CC (▲), FC (■), DA (●) and for the mixture, CFD (◆) corresponding to a ratio of 1.375:1:7 CC:FC:DA, in ethanol solution.

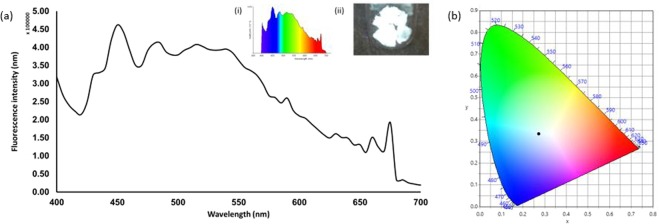

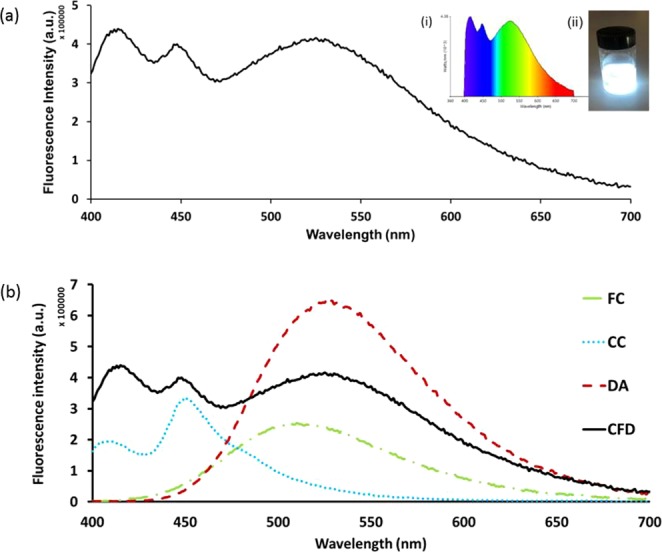

The emission spectrum corresponding to point CFD covered the entire visible region (400–700 nm) (Fig. 5), with three emission maxima at 430, 450 and 525 nm. These bands appear to be similar to the individual CC, FC and DA emissions, indicating that the emission spectra are due to the simultaneous emission from all of the fluorescents. The fluorescence analysis from the mixture clearly shows that excitation at 390 nm results in emission that broadly covers the entire visible range up to about 700 nm. The absorption and emission spectra of the fluorescents do not exhibit any significant overlap (CC, FC and DA: absorption band (300–400 nm), emission band (400–700 nm)). Furthermore, by comparing the emission spectrum of the mixture CFD with the spectrum from each individual compound (Fig. 5(b)), there is very little/no peak shifting which indicates that simultaneous emission occurs which results in white light generation. Examining the individual emission responses of FC and CC (Fig. 5(b)) there is also the possibility that self-absorption may be occurring and it is expected that this may become more apparent at higher concentrations47,48. Observations from a complimentary experiment in which the amount of DA was increased 7-fold and added to a fixed CC:FC (1.375:1) ratio, given in (Table S1), show the production of WLE at 390 nm. Furthermore, the CIE coordinates, correlated colour temperature (CCT) and photograph under UV lamp illumination (390 nm) are given for various ratio combinations of the fluorescents in ethanol. As is seen in Table S1, simple variations in relative composition of the components modifies the CIE indices and the corresponding colour temperatures in a facile manner.

Figure 5.

(a) Fluorescence spectrum for a mixture, CFD, of CC:FC:DA (1.375:1:7) in ethanol at 390 nm. Inset: (i) Colour spectrum and (ii) photograph of the CFD solution in ethanol under UV light (390 nm). (b) Shows overlay of both fluorescence spectrum from a mixture (CFD, where CC:FC:DA = 1.375:1:7) and the fluorescence spectra of the three components individually (FC, CC, DA) in ethanol at 390 nm.

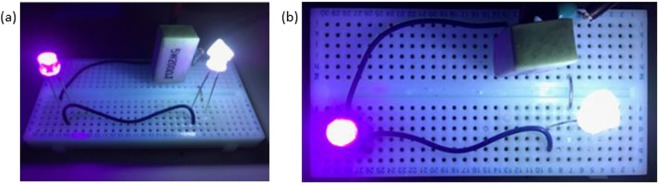

The possibility of producing WLE with this simple mixture from a solid media has also been explored. Aerogels offer high porosity (nanometer-scale pore sizes), they are lightweight materials with low densities (0.003–0.15 kg/m3) and large surface areas (500–1000 m2/g)49,50. Such properties mean that aerogel has great potential for use in a wide range of applications, including thermal insulation51, electrochemical applications (e.g., super capacitors)52, materials for tissue engineering53, bio-sensors54, amongst several others. In this work, we tested two commercially available aerogel variants: dry hydrophilic and dry hydrophobic silica aerogel. The hydrophilic aerogel produces white light upon excitation after soaking in the WLE mixture, whilst the hydrophobic aerogel produced a blue light emission. The aerogel was soaked in the WLE mixture in ethanol for 3 days in a fume hood. Subsequently, the gel was filtered and allowed to dry. The dried aerogel then exhibits WLE when excited under UV light illumination. The fluorescence emission spectrum of the mixture incorporated in to aerogel is shown in Fig. 6a, which covered the visible region from 400 to 650 nm. The aerogel shows good WLE under UV light (inset, Fig. 6a(ii)). A good CIE coordinate value of (0.27, 0.33) was obtained for the WLE aerogel from the corresponding emission spectrum, excited at 390 nm (Fig. 6b). Finally, as an exemplar application to demonstrate the potential of this approach, we applied the WLE aerogel in an ad-hoc fashion as a coating for a commercial UV LED. Side by side images of the regular UV LED and the modified aerogel WLE LED are shown in Fig. 7. As can be observed, the modified LED produces a uniform WLE.

Figure 6.

WLE aerogel. (a) Emission spectrum of mixture incorporated in to aerogel for WLE. Inset (i) Colour spectrum of the modified aerogel and (ii) photograph of the modified aerogel under UV illumination (390 nm). (b) CIE plot for colour coordinate of white light emitting aerogel (0.27,0.33).

Figure 7.

Side-by-side image for the same UV LED. In each image the left hand side is the uncoated UV LED and the right hand side LED is coated with aerogel to produce WLE. Both images are taken of the same experimental setup: (a) is a side view and (b) is a top view.

Conclusion

In summary, we have produced WLE from three simple organic compounds two of which were synthesised using a simple procedure. The optimised mixture of furocoumarin, dansyl aniline and 7-hydroxycoumarin-3-carboxylic acid at a ratio 1.375:1:7 in ethanol, generates almost pure white light, with identical CIE values in solution and when immobilised in solid silica aerogel, (0.27, 0.33). WLE from simple organic materials offers significant potential for applications in the global lighting industry. When immobilised in aerogel and applied to a commercial UV LED, it was demonstrated how this approach can produce effective WLE. Following this approach can open up further research avenues utilising aerogels to provide thermal insulation for solid state lighting applications. Furthermore, it would be interesting to see if such a system can be used as a dye for tuneable dye laser applications. To the best of our knowledge, this is a unique mixture of simple organic molecules that when combined can produce WLE in solution and also solid media (i.e., aerogel).

Materials and Methods

All starting materials and reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (UK). They were used without further purification. Hydrophilic aerogel was obtained from Cabot Corporation (USA) for WLE solid preparation. 1H NMR (400 MHz) spectra were measured on a Bruker Biospin DRX-600 spectrometer using TMS as an internal standard. 7-hydroxy-3-carboxylic acid coumarin (CC) (Mw = 206.15 g/mol, Sigma Aldrich) was used as a blue-purple emitting material. UV-vis absorption and fluorescence spectra in solution were recorded on a Cary 5000 UV-Vis-NIR Spectrophotometer from Agilent Technologies and FLS 1000 Spectrometer from Edinburgh Instruments, respectively. Excitation and emission monochromator band pass were kept at 1 nm using a quartz cell cuvette (1 × 1 cm). CIE colour coordinates have been calculated using freely available Osram Sylvania software.

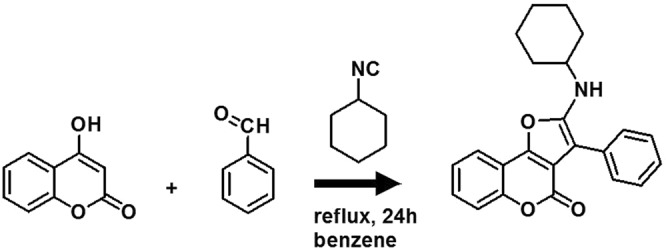

Synthesis of furo [3,2-c] coumarin (FC)

4-hydroxycoumarin (4.86 g, 30 mmol, 1 eq.) and benzaldehyde (3.18 g, 30 mmol, 1 eq.) were dissolved in benzene (150 mL) and heated to reflux (Fig. 8). After 30 minutes, cyclohexyl isocyanide (3.27 g, 30 mmol, 1 eq.) was added to the reaction mixture, which was heated to reflux for a further 24 h. The pure compound was obtained by recrystallization from diethyl ether (100 mL) to yield a bright yellow crystalline powder (9.70 g, 90% yield). Analysis was in agreement with the literature44. Figure 8 shows the schematic of the reaction. Melting point = 110–112 °C, FTIR = 3289 (NH), 2930–2857 (cyclohexane), 1707 (C=O of pyrone), 1593 (C=C of pyrone). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.80 (d, J = 7.27 Hz, 1H, Ar), 7.50 (d, J = 7.27 Hz, 2H, Ar), 7.43–7.45 (m, 4H, Ar), 7.34–7.35 (m, 2H, Ar), 4.23 (s, 1H), 3.60 (s, 1H), 1.26–2.01 (m, 10H). 13C NMR: δ 24.19, 25.54, 34.15, 53.69, 77.05, 97.47, 110.94, 112.87, 117.29, 119.49, 123.95, 124.89, 127.01, 128.66, 129.19, 130.73, 132.87, 149.81, 151.32, 154.89, 157.95. UV-Vis = 374 nm in ethanol. MS (ESI) = m/z 360.

Figure 8.

Synthesis of furo[3,2-c]coumarin derivatives.

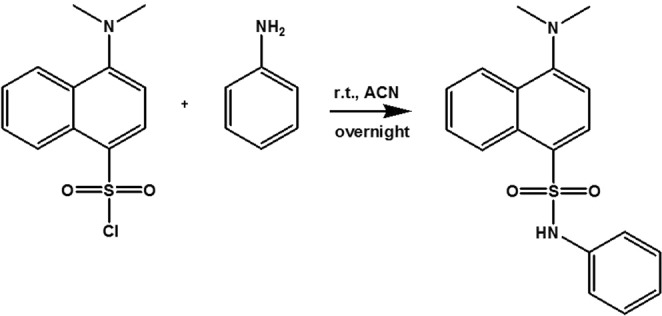

Synthesis of dansyl aniline (DA)

Dansyl chloride (2.69 g, 10 mmol, 1 eq.) and aniline (9.30 g, 10 mmol, 1 eq.) were dissolved and stirred in acetonitrile (50 mL) overnight (Fig. 9). The pure compound was obtained by recrystallization from distilled water and ethanol to produce up to 65% yield (2.12 g). Analysis was in agreement with the literature45. Figure 9 shows the schematic of the reaction. Yellow powder, m.p. = 131–133 °C, FTIR = 3270 (NH), 2833 (N-CH3), 1601 (NH-aromatic), 1349 (SO2-NH), 1159 (SO2 stretching). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 8.52 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar), 8.35 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar), 8.16 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz, Ar), 7.61 (t, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz, Ar), 7.45 (t, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar), 7.22–7.20 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz, Ar), 7.17–7.13 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.07–7.05 (m, 1H, Ar), 6.95–6.93 (d, 2H, J = 8 Hz, Ar), 6.68 (s, 1H), 2.90 ppm (s, 6H, N(CH3)2). 13C NMR: δ162.96, 152.18, 138.79, 133.17, 132.29, 132.11, 130.83, 130.39, 129.16, 128.61, 125.40, 121.80, 117.88, 115.22, 77.33, 77.02, 76.70, 45.41. UV-Vis = 339 nm in ethanol. MS (ESI) = m/z 327.

Figure 9.

Synthesis of dansyl aniline.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

N.M.S. acknowledges Dual PhD Program (University of Malaya-University of Liverpool) sponsored by University of Malaya, MyBrain15 (MyPhD), FRGS grant (FP070-2018A), Faculty Program - Research University Grant (GPF048B-2018), and UMRG grant (RG340-15AFR) and postgraduate grant (PG356-2016A). N.M.S. is grateful to Cedric Boisdon (Research Assistant to S.M.) for his helpful advice and assistance. A.G.S. acknowledges a Royal Society-EPSRC Dorothy Hodgkin Research Fellowship.

Author Contributions

S.M. and H.A.T. designed the project. Experiments were performed by N.M.S. The manuscript and figures were prepared by N.M.S. and S.M. Various aspects of the research ideas described were initiated and developed by P.M., A.S., B.S., H.A.T. and Z.A. All authors reviewed the manuscript and Supplementary Information.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-47847-5.

References

- 1.Klauk, H. Organic electronics: materials, manufacturing, and applications. (John Wiley & Sons, 2006).

- 2.Singh V, Mishra AK. White light emission from vegetable extracts. Scientific reports. 2015;5:11118. doi: 10.1038/srep11118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galas L, et al. Probe, Sample, and Instrument (PSI): The Hat-Trick for Fluorescence Live Cell Imaging. Chemosensors. 2018;6:40. doi: 10.3390/chemosensors6030040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han Y, Li M, Qiu F, Zhang M, Zhang Y-H. Cell-permeable organic fluorescent probes for live-cell long-term super-resolution imaging reveal lysosome-mitochondrion interactions. Nature Communications. 2017;8:1307. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01503-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCann TE, et al. Activatable Optical Imaging with a Silica-Rhodamine Based Near Infrared (SiR700) Fluorophore: A comparison with cyanine based dyes. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2011;22:2531–2538. doi: 10.1021/bc2003617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolemen, S. & Akkaya, E. Reaction-based BODIPY probes for selective bio-imaging. Vol. 354 (2017).

- 7.Sozmen, F. et al. Designing BODIPY-based probes for fluorescence imaging of β-amyloid plaques. Vol. 4 (2014).

- 8.Atilgan, S., Ozdemir, T. & Akkaya, E. Selective Hg(II) Sensing with Improved Stokes Shift by Coupling the Internal Charge Transfer Process to Excitation Energy Transfer. Vol. 12 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Coskun, A., Deniz, E. & Akkaya, E. A sensitive fluorescent chemosensor for anions based on a styryl–boradiazaindacene framework. Vol. 48 (2007).

- 10.Wu D, et al. Fluorescent chemosensors: the past, present and future. Chemical Society Reviews. 2017;46:7105–7123. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00240H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bozdemir OA, et al. Selective Manipulation of ICT and PET Processes in Styryl-Bodipy Derivatives: Applications in Molecular Logic and Fluorescence Sensing of Metal Ions. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:8029–8036. doi: 10.1021/ja1008163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, et al. Near-Infrared Upconversion Chemodosimeter for In Vivo Detection of Cu2+ in Wilson Disease. Advanced Materials. 2016;28:6625–6630. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maher, S. et al. In 2016 IEEE SENSORS. 1–3 (IEEE).

- 14.Mukherjee S, Thilagar P. Organic white-light emitting materials. Dyes and Pigments. 2014;110:2–27. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2014.05.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawken, P., Lovins, A. B. & Lovins, L. H. Natural capitalism: The next industrial revolution. (Routledge, 2013).

- 16.Jang E, et al. White-light-emitting diodes with quantum dot color converters for display backlights. Advanced materials. 2010;22:3076–3080. doi: 10.1002/adma.201000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiao G-S, Thoresen LH, Burgess K. Fluorescent, Through-Bond Energy Transfer Cassettes for Labeling Multiple Biological Molecules in One Experiment. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:14668–14669. doi: 10.1021/ja037193l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang, C. et al. Recent Progress in Polymer White Light-Emitting Materials and Devices. Vol. 214 (2013).

- 19.Singh V, Mishra AK. White light emission from an aqueous vegetable cocktail: Application towards pH sensing. Dyes and Pigments. 2016;125:362–366. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2015.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park Y, et al. A new pH sensitive fluorescent and white light emissive material through controlled intermolecular charge transfer. Chemical science. 2015;6:789–797. doi: 10.1039/C4SC01911C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanju KS, Neelakandan PP, Ramaiah D. DNA-assisted white light emission through FRET. Chemical Communications. 2011;47:1288–1290. doi: 10.1039/C0CC04173D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maiti DK, Bhattacharjee R, Datta A, Banerjee A. Modulation of Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Efficiency for White Light Emission from a Series of Stilbene-Perylene Based Donor–Acceptor Pair. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2013;117:23178–23189. doi: 10.1021/jp409042p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh V, Mishra AK. White light emission from a mixture of pomegranate extract and carbon nanoparticles obtained from the extract. Journal of Materials Chemistry C. 2016;4:3131–3137. doi: 10.1039/C6TC00480F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benelhadj K, et al. White Emitters by Tuning the Excited-State Intramolecular Proton-Transfer Fluorescence Emission in 2-(2′-Hydroxybenzofuran) benzoxazole Dyes. Chemistry–A European Journal. 2014;20:12843–12857. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maity A, Ali F, Agarwalla H, Anothumakkool B, Das A. Tuning of multiple luminescence outputs and white-light emission from a single gelator molecule through an ESIPT coupled AIEE process. Chemical Communications. 2015;51:2130–2133. doi: 10.1039/C4CC09211B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molla MR, Ghosh S. Hydrogen-bonding-mediated J-aggregation and white-light emission from a remarkably simple, single-component, naphthalenediimide chromophore. Chemistry–A European Journal. 2012;18:1290–1294. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Nishiura M, Wang Y, Hou Z. π-Conjugated aromatic enynes as a single-emitting component for white electroluminescence. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:5592–5593. doi: 10.1021/ja058188f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang N-N, et al. Single-component small-molecule white light organic phosphors. Chemical Communications. 2017;53:9269–9272. doi: 10.1039/C7CC05446G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicolai HT, Hof A, Blom PW. Device Physics of White Polymer Light-Emitting Diodes. Advanced Functional Materials. 2012;22:2040–2047. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201102699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun C-Y, et al. Efficient and tunable white-light emission of metal–organic frameworks by iridium-complex encapsulation. Nature communications. 2013;4:2717. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Q-Y, et al. Pure white-light and yellow-to-blue emission tuning in single crystals of Dy (III) metal–organic frameworks. Chemical Communications. 2014;50:7702–7704. doi: 10.1039/C4CC01763C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sessolo M, Tordera D, Bolink HJ. Ionic iridium complex and conjugated polymer used to solution-process a bilayer white light-emitting diode. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2013;5:630–634. doi: 10.1021/am302033k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ledemi Y, et al. White light and multicolor emission tuning in triply doped Yb 3+/Tm 3+/Er 3+ novel fluoro-phosphate transparent glass-ceramics. Journal of Materials Chemistry C. 2014;2:5046–5056. doi: 10.1039/C4TC00455H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanju KS, Ramaiah D. White photoluminescence and electroluminescence from a ternary system in solution and a polymer matrix. Chemical Communications. 2013;49:11626–11628. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43494j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giansante C, et al. White-Light-Emitting Self-Assembled NanoFibers and Their Evidence by Microspectroscopy of Individual Objects. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:316–325. doi: 10.1021/ja106807u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giansante C, Schäfer C, Raffy G, Del Guerzo A. Exploiting Direct and Cascade Energy Transfer for Color-Tunable and White-Light Emission in Three-Component Self-Assembled Nanofibers. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2012;116:21706–21716. doi: 10.1021/jp3073188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abbel R, et al. Multicolour Self-Assembled Fluorene Co-Oligomers: From Molecules to the Solid State via White-Light-Emitting Organogels. Chemistry–A European Journal. 2009;15:9737–9746. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vijayakumar C, Sugiyasu K, Takeuchi M. Oligofluorene-based electrophoretic nanoparticles in aqueous medium as a donor scaffold for fluorescence resonance energy transfer and white-light emission. Chemical Science. 2011;2:291–294. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00343C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Yan J, Zhou Y, Pei J. Surface modification of self-assembled one-dimensional organic structures: white-light emission and beyond. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:15872–15874. doi: 10.1021/ja106354m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, R., Peng, J., Qiu, F., Yang, Y. & Xie, Z. Simultaneous blue, green, and red emission from diblock copolymer micellar films: A new approach to white-light emission. Chemical Communications, 6723–6725 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Wang R, Peng J, Qiu F, Yang Y. Enhanced white-light emission from multiple fluorophores encapsulated in a single layer of diblock copolymer micelles. Chemical Communications. 2011;47:2787–2789. doi: 10.1039/C0CC04955G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balan B, Vijayakumar C, Ogi S, Takeuchi M. Oligofluorene-based nanoparticles in aqueous medium: hydrogen bond assisted modulation of functional properties and color tunable FRET emission. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2012;22:11224–11234. doi: 10.1039/c2jm30315a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melucci M, et al. Facile tuning from blue to white emission in silica nanoparticles doped with oligothiophene fluorophores. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2010;20:9903–9909. doi: 10.1039/c0jm01579b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nair V, Menon RS, Vinod A, Viji S. A facile three-component reaction involving [4 + 1] cycloaddition leading to furan annulated heterocycles. Tetrahedron letters. 2002;43:2293–2295. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)00226-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao Y, et al. A dansyl-based fluorescent probe for the highly selective detection of cysteine based on a d-PeT switching mechanism. RSC Advances. 2017;7:21050–21053. doi: 10.1039/C7RA00212B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y, et al. An organic white light-emitting fluorophore. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:14081–14092. doi: 10.1021/ja0632207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oliva J, et al. Tunable white light from photo-and electroluminescence of ZnO nanoparticles. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2013;47:015104. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/47/1/015104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, et al. Key issues and recent progress of high efficient organic light-emitting diodes. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C: Photochemistry Reviews. 2013;17:69–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2013.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karaaslan, M. A., Kadla, J. F. & Ko, F. K. In Lignin in Polymer Composites (eds Omar Faruk & Mohini Sain) 67–93 (William Andrew Publishing, 2016).

- 50.Smirnova I, Gurikov P. Aerogel production: Current status, research directions, and future opportunities. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 2018;134:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.12.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mishra R, Kotresh TM, Militky J, Jamshaid H. Aerogels for thermal insulation in high-performance textiles AU - Venkataraman, M. Textile Progress. 2016;48:55–118. doi: 10.1080/00405167.2016.1179477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Araby S, et al. Aerogels based on carbon nanomaterials. Journal of Materials Science. 2016;51:9157–9189. doi: 10.1007/s10853-016-0141-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maleki H, et al. Synthesis and biomedical applications of aerogels: Possibilities and challenges. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2016;236:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wen D, Liu W, Herrmann AK, Eychmüller A. A membraneless glucose/O2 biofuel cell based on Pd aerogels. Chemistry–A European Journal. 2014;20:4380–4385. doi: 10.1002/chem.201304635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.