Abstract

To date, the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection in patients with stage II colon cancer remains controversial. Still, little is known about the effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage II colon cancer who are older than 70 years, as most studies did not focus on this population. This study aimed to investigate the oncologic outcomes of elderly patients with stage II colon cancer who underwent curative resection with or without postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. We retrospectively reviewed medical records of patients older than 70 years who underwent curative resection of stage II primary colon cancer during 2002–2015. Patients were classified into surgery alone (SA) and adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) groups and propensity score-matched at a 1:1 ratio using a logistic regression. The end points were recurrence-free (RFS), cancer-specific (CSS) and overall survival (OS). Of the 623 patients who met the criteria, 145 were assigned to each arm after propensity score matching. The mean ages of the SA and AC groups were 74.3 and 74.0 years, respectively. A log-rank test revealed no significant inter-group differences in RFS (p = 0.202), CSS (p = 0.486) or OS (p = 0.299). In a Cox regression analysis, adjuvant chemotherapy was not found to be an independent factor affecting RFS (p = 0.206), CSS (p = 0.487) or OS (p = 0.301). Adjuvant chemotherapy does not appear to yield survival benefits in elderly patients with stage II colon cancer.

Subject terms: Surgical oncology, Colon cancer

Introduction

The number of elderly patients diagnosed with colon cancer continues to increase worldwide, in parallel with population aging1. However, no guideline for the management of colon cancer in this population has been established because elderly patients generally have been excluded from randomized control studies2. A recent review has highlighted the problems of a lack of evidence and under-representation of elderly patients in clinical trials on the specific effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients because of strict age-based inclusion and exclusion criteria3. In one study of data from Medicare and the Texas Cancer Registry, Zhao and colleagues reported that guideline-concordant treatment, including adjuvant chemotherapy, was associated with better survival outcomes among elderly patients with stage II and stage III colon cancer4. However, elderly patients tend to have a poorer general condition, compared to their younger counterparts, and may therefore face an increased risk of morbidity and mortality associated with chemotherapy-related adverse effects5–7.

The effect of adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection in stage II colon cancer patients remains controversial. Some studies reported that adjuvant chemotherapy confers survival benefits8,9, whereas other recent studies suggest a lack of association with improved survival gain9–12. However, as most previous studies did not focus on patients older than 70 years, little information is available about the potential benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer in this population. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the oncologic outcomes, including recurrence-free (RFS), cancer-specific (CSS) and overall survival (OS), in elderly patients with stage II colon cancer who underwent curative resection with or without adjuvant chemotherapy. We hypothesize that these two groups of patients would achieve different survival outcomes.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital. The IRB waived the requirement for informed consent because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients older than 70 years who underwent curative resection of stage II primary colon cancer at Seoul National University Hospital from 2002 to 2015. Patients with a history of other malignancy or missing data regarding the body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification and/or pathologic results (e.g., perineural, venous, lymphatic invasion) were excluded. The remaining patients were divided into two groups: the adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) group comprised patients who received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, while patients in the surgery alone (SA) group underwent surgery alone.

Variables

The following preoperative clinical variables were evaluated: age, sex, ASA classification, BMI, pre-existing disease (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, pulmonary disease), tumor sidedness, preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen(CEA) level and presence of perforation/obstruction. Additionally, the operation type, postoperative complications and pathologic variables (e.g., pT, harvested lymph nodes [LN] and lymphatic, venous and perineural invasion) were reviewed. Heart disease included ischemic heart disease (e.g., myocardial infarction, angina), arrhythmia, valvular disease and chronic heart failure. Pulmonary disease included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma and previous tuberculosis. Cancers from the cecum to transverse colon were defined as right-sided, while those from the splenic flexure to sigmoid colon were defined as left-sided. Complications was classified using the Clavien–Dindo classification. High-risk features included a poorly differentiated histology, perforation, bowel obstruction, <12 examined LN, lymphatic/vascular invasion or perineural invasion, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline13.

Procedure

All patients underwent curative resection, including D2 LN dissection. Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered 4 weeks postoperatively if the patient was deemed to have recovered. Most patients received the planned cycle of a fluorouracil (FU)-based chemotherapy regimen. All patients were recommended to attend follow-up visits every 3–6 months for the first 2 years and every 6 months thereafter for a total of 5 years. During these regular follow-ups, recurrences were detected through colonoscopy, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations.

Survival data

The follow-up of older patients may be challenging. Therefore, survival data were obtained from Statistics Korea (KOSTAT), which records the date and cause of each death and is updated every 2 years. The most recent update occurred on December 31, 2016. The causes of death are stored using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code corresponding to the version current at the time of recording. Death from colon cancer was recorded as C18 during the period of 2002–2016.

Primary outcomes

The primary endpoints were RFS, CSS and OS, which were compared between groups. RFS was calculated from the date of operation to the date of diagnosis of recurrence or death from any cause. CSS and OS were calculated from the date of operation to the date of death from colon cancer and to the date of death from any cause, respectively.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 25.0 for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Categorical baseline characteristics were analyzed using the χ2-test or linear-by-linear association, and continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The two groups of patients were balanced using propensity score matching, which included a logistic regression with 1:1 nearest neighbor matching and a caliper of 0.2. The following covariables included: age, sex, ASA classification, BMI, perforation, obstruction, HTN, cardiac disease, pulmonary disease, tumor sidedness, operation type, tumor differentiation, size, pT, harvested LN, lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, perineural invasion

Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test were used to evaluate the 5-year RFS, CSS and OS rates. A Cox regression hazard model was generated to identify the factors significantly affecting RFS, CSS and OS, and the multivariable analysis included factors with a p value < 0.2 in the univariable analysis.

Results

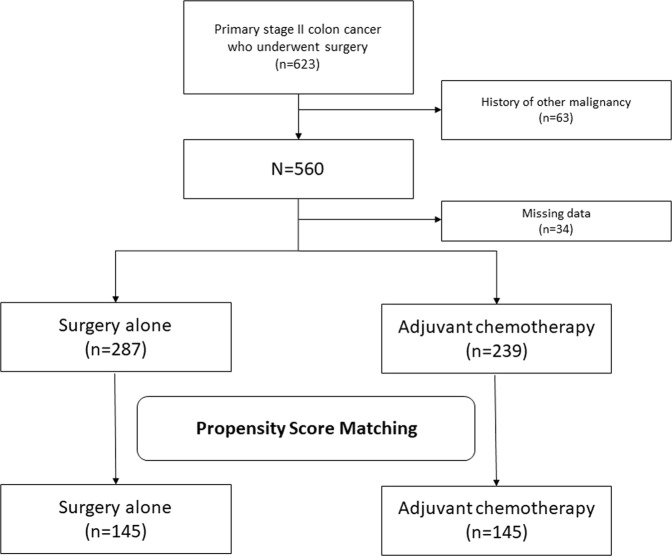

A total of 623 patients underwent curative resection at our institution between 2002 and 2015. Of these, 63 patients and 34 patients were excluded because of a history of other malignancy and missing data, respectively. Finally, 526 patients were included in our analysis (Fig. 1). Their baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Briefly, the overall mean age was 75.7 years (range: 70–93 years), and there was a slight male predominance (300/526, 57%).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient selection.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Surgery alone (n = 287) | Adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 239) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 77.8 ± 5.0 | 73.2 ± 2.8 | 0.01 |

| Sex | 0.514 | ||

| Male | 160 (55.7%) | 140 (58.6%) | |

| Female | 127 (44.3%) | 99 (41.4%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.3 ± 3.3 | 23.1 ± 3.1 | 0.01 |

| ASA classification | 0.003 | ||

| 1 | 38 (13.2%) | 55 (23.0%) | |

| 2 | 214 (74.6%) | 164 (68.6%) | |

| 3 | 35 (12.2%) | 20 (8.4%) | |

| Diabetes | 64 (22.3%) | 53 (22.2%) | 0.973 |

| Hypertension | 168 (58.5%) | 114 (47.7%) | 0.013 |

| Cardiac disease | 27 (9.4%) | 13 (5.4%) | 0.087 |

| Pulmonary disease | 24 (8.4%) | 17 (7.1%) | |

| Tumor side | 0.529 | ||

| Right-sided | 129 (44.9%) | 114 (47.7%) | |

| Left-sided | 158 (55.1%) | 125 (52.3%) | |

| Preoperative CEA (ng/mL) | 8.9 ± 34.0 | 5.7 ± 10.6 | 0.146 |

| Perforation | 8 (2.8%) | 5(2.1%) | 0.609 |

| Obstruction | 89 (31.0%) | 50 (20.9%) | 0.009 |

| Operation type | 0.487 | ||

| Open | 227 (79.1%) | 183 (76.6%) | |

| Laparoscopy | 60 (20.9%) | 56 (23.4%) | |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.096 | ||

| WD | 13 (4.5%) | 16 (6.7%) | |

| MD | 245 (85.4%) | 209 (87.4%) | |

| PD | 15 (5.2%) | 5 (2.1%) | |

| Mucinous | 8 (2.8%) | 7 (2.9%) | |

| Others | 6 (2.1%)a | 2 (0.8%)b | |

| Size (cm) | 5.7 ± 2.4 | 5.3 ± 2.3 | 0.029 |

| Pathologic T stage | 0.113 | ||

| 3 | 259 (90.2%) | 205 (85.8%) | |

| 4 | 28 (9.8%) | 34 (12.2%) | |

| The number of harvested LN | 0.962 | ||

| <12 | 44 (15.3%) | 37 (15.5%) | |

| ≥12 | 243 (84.7%) | 202 (84.5%) | |

| Lymphatic invasion | 47 (16.4%) | 46 (19.2%) | 0.39 |

| Venous invasion | 15 (5.2%) | 25 (10.5%) | 0.024 |

| Perineural invasion | 53 (18.5%) | 59 (24.7%) | 0.083 |

| Postoperative complication | 40 (13.9%) | 25 (10.5%) | 0.228 |

| Clavien–Dindo classification | 0.075 | ||

| 1 | 18 | 15 | |

| 2 | 6 | 2 | |

| 3 | 8 | 7 | |

| 4 | 7 | 1 | |

| 5 | 1 | 0 |

aMedullary carcinoma (1), serrated adenocarcinoma (3), mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma (1) and unknown information for differentiation (1).

bSerrated adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma.

BMI, body mass index; ASA classification, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; WD, well-differentiated; MD, moderately differentiated; PD, poorly differentiated; LN, lymph node.

In an initial group comparison, patients in the SA group were older and had a lower BMI, higher ASA classification, larger tumor size and more frequent venous invasion, compared to the AC group. After propensity score matching to balance the pre-existing and pathologic variables, 145 patients were assigned to each arm. The mean ages of the matched SA and AC groups were 74.3 and 74.0 years, respectively (Table 2). In the AC group, after propensity score matching, the regimens followed were: 5-FU (n = 61), capecitabine (n = 40), capecitabine and oxaliplatin (n = 1), uracil/tegafur (UFT; n = 18), folinic acid-FU-oxaliplatin (FOLFOX; n = 21), and unknown (as the patients received chemotherapy at other hospitals; n = 4).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics after propensity score matching.

| Surgery alone (n = 145) | Adjuvant chemotherapy(n = 145) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74.3 ± 3.0 | 74.0 ± 3.0 | 0.309 |

| Sex | 0.473 | ||

| Male | 89 (61.4%) | 83 (57.2%) | |

| Female | 56 (38.6%) | 62 (42.8%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.6 ± 3.4 | 22.8 ± 2.7 | 0.6 |

| ASA classification | 0.106 | ||

| 1 | 19 (13.1%) | 34 (23.4%) | |

| 2 | 109 (75.2%) | 94 (64.8%) | |

| 3 | 17 (11.7%) | 17 (11.7%) | |

| Diabetes | 35 (24.1%) | 35 (24.1%) | >0.999 |

| Hypertension | 77 (53.1%) | 76 (52.4%) | 0.906 |

| Cardiac disease | 14 (9.7%) | 11 (7.6%) | 0.53 |

| Pulmonary disease | 13 (9.0%) | 11 (7.6%) | 0.67 |

| Tumor side | 0.813 | ||

| Right-sided | 64 (44.1%) | 66 (45.5%) | |

| Left-sided | 81 (55.9%) | 79 (54.5%) | |

| Preoperative CEA (ng/mL) | 9.7 ± 44.3 | 5.9 ± 11.8 | 0.341 |

| Perforation | 4 (2.8%) | 2 (1.4%) | 0.684 |

| Obstruction | 39 (26.9%) | 35 (24.1%) | 0.59 |

| Operation type | 0.666 | ||

| Open | 116 (80.0%) | 113 (77.9%) | |

| Laparoscopy | 29 (20.0%) | 32 (22.1%) | |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.434 | ||

| WD | 8 (5.5%) | 8 (2.1%) | |

| MD | 125 (86.2%) | 128 (88.3%) | |

| PD | 6 (4.1%) | 3 (2.1%) | |

| Mucinous | 3 (2.1%) | 5 (3.4%) | |

| Others | 3 (2.1%)a | 1 (0.7%)b | |

| Size (cm) | 5.3 ± 2.2 | 5.2 ± 2.2 | 0.69 |

| Pathologic T stage | 0.312 | ||

| 3 | 129 (89%) | 134 (92.4%) | |

| 4 | 16 (11.0%) | 11 (7.6%) | |

| The number of harvested LN | 0.441 | ||

| <12 | 28 (19.3%) | 23 (15.9%) | |

| ≥12 | 117 (80.7%) | 122 (84.1%) | |

| Lymphatic invasion | 23 (15.9%) | 18 (12.4%) | 0.399 |

| Venous invasion | 6 (4.8%) | 6 (4.8%) | >0.999 |

| Perineural invasion | 32 (22.1%) | 35 (24.1%) | 0.676 |

| Postoperative complication | 17 (11.7%) | 15 (10.3%) | 0.708 |

| Clavien-Dindo classification | 0.149 | ||

| 1 | 6 | 10 | |

| 2 | 4 | 2 | |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| 4 | 4 | 1 | |

| 5 | 1 | 0 |

aMedullary carcinoma (1) and serrated adenocarcinoma (2).

bAdenosquamous carcinoma.

BMI, body mass index; ASA classification, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; WD, well-differentiated; MD, moderately differentiated; PD, poorly differentiated; LN, lymph node.

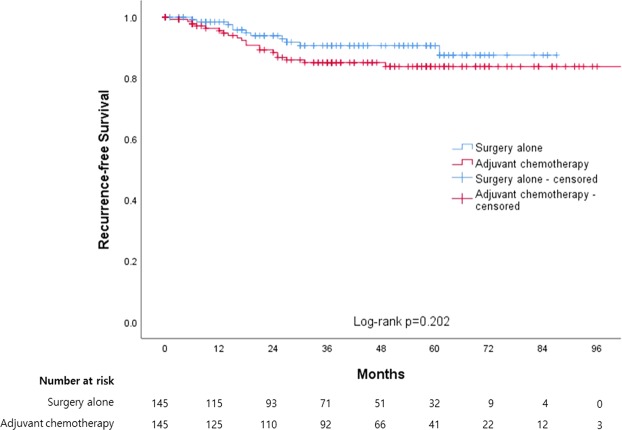

Recurrence-free survival (RFS)

All patients were followed to detect recurrence for a mean of 1337.7 days (range: 15–3403 days). Recurrence was detected in 11 (7.6%) and 20 patients (13.8%) in the SA and AC groups, respectively, which had median RFS durations of 79.8 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 75.8–83.9) and 96.1 months (95% CI: 90.1–102.1), respectively, as determined using Kaplan–Meier curves (Fig. 2). The corresponding 5-year RFS rates were 91.8 and 85.1%, respectively, and this difference was not statistically significant (log-rank test, p = 0.202).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves between surgery alone and adjuvant chemotherapy for recurrence-free survival.

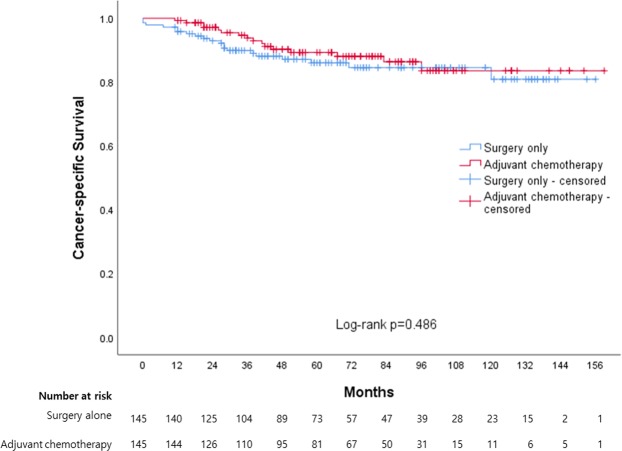

Cancer-specific survival and overall survival

The mean survival follow-up duration was 2049.5 days (range: 26–4853 days). Thirty-eight (26.2%) and 29 patients (20.0%) in the SA and AC groups, respectively, died during this period, and the cause of death was colon cancer in 20 and 16 patients, respectively. A Kaplan–Meier analysis yielded median CSS durations of 135.0 (95% CI: 126.6–143.5) and 141.3 months (95% CI: 133.1–149.5) months in the SA and AC groups, respectively, which had 5-year CSS rates of 86.0 and 89.3%, respectively (Fig. 3). This difference was not statistically significant (log-rank test, p = 0.486).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves between surgery alone and adjuvant chemotherapy for cancer-specific survival.

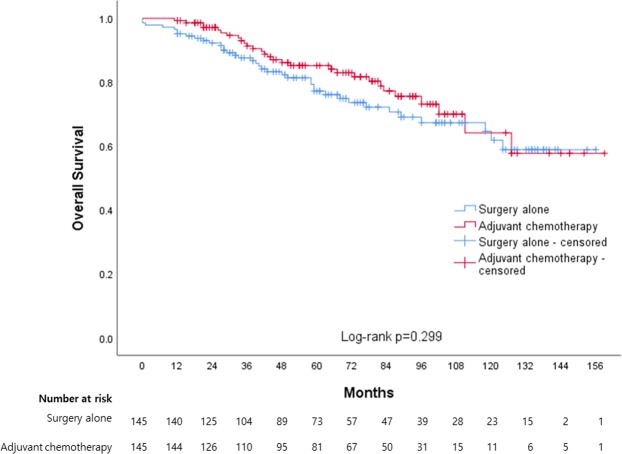

The median OS durations in the SA and AC groups were 117.3 (95% CI: 107.2–127.4) and 124.5 months (95% CI: 113.4–135.5) months, respectively (Fig. 4). The corresponding 5-year OS rates were 81.4 and 85.2%, and this difference was not statistically significant (log-rank test, p = 0.299).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves between surgery alone and adjuvant chemotherapy for overall survival.

Factors associated with RFS, CSS and OS

RFS

In a univariable analysis, age, pulmonary disease, preoperative CEA level and lymphatic, venous and perineural invasion were identified as statistically significant factors for RFS. In a multivariable analysis, the CEA level (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00–1.01), venous invasion (HR: 3.57, 95% CI: 1.15–11.06) and perineural invasion (HR: 3.40, 95% CI: 1.47–7.85) remained independent and significant factors affecting RFS (Table 3). However, adjuvant chemotherapy was not identified as a significant factor (HR: 1.61, 95% CI: 0.77–3.36).

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable analyses to identify factors affecting recurrence-free survival, cancer specific survival and overall survival.

| RFS | CSS | OS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable† | Univariable | Multivariable† | Univariable | Multivariable† | |||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (years) | 1.12 (1.00–1.25) | 0.044 | 1.01 (0.89–1.15) | 0.9 | 1.15 (1.03–1.28) | 0.01 | 1.05 (0.92–1.21) | 0.437 | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) | 0.016 | 1.07 (0.98–1.17) | 0.158 |

| Sex | 0.195 | 0.116 | 0.192 | 0.126 | 0.003 | 0.003 | ||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Female | 0.61 (0.29–1.29) | 0.49 (0.20–1.19) | 0.62 (0.31–1.27) | 0.53 (0.24–1.19) | 0.42 (0.24–0.74) | 0.40 (0.21–0.73) | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.03 (0.92–1.16) | 0.615 | 0.879 (0.78–0.99) | 0.03 | 0.97 (0.84–1.11) | 0.65 | 0.89 (0.82–0.97) | 0.009 | 0.93 (0.84–1.03) | 0.171 | ||

| ASA | 0.35 | 0.056 | 0.13 | 0.037 | 0.08 | |||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| ≥2 | 1.65 (0.58–4.72) | 4.01 (0.96–16.70) | 4.82 (0.63–36.89) | 2.45 (1.06–5.66) | 2.58 (0.89–7.43) | |||||||

| Diabetes | 1.26 (0.56–2.82) | 0.575 | 1.41 (0.69–2.87) | 0.342 | 0.92 (0.52–1.64) | 0.781 | ||||||

| Hypertension | 1.39 (0.68–2.84) | 0.364 | 1.22 (0.63–2.36) | 0.558 | 1.52 (0.93–2.49) | 0.094 | 1.66 (0.95–2.91) | 0.075 | ||||

| Cardiac disease | 1.53 (0.54–4.39) | 0.424 | 1.07 (0.33–3.49) | 0.91 | 1.60 (0.76–3.35) | 0.214 | ||||||

| Pulmonary disease | 2.94 (1.13–7.67) | 0.027 | 1.00 (0.26–3.85) | 0.998 | 2.51 (0.97–6.48) | 0.057 | 1.73 (0.44–6.82) | 0.437 | 2.14 (1.02–4.49) | 0.045 | 3.02 (1.20–7.59) | 0.018 |

| Tumor side | 0.531 | 0.223 | 0.291 | |||||||||

| Right-sided | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Left-sided | 1.26 (0.62–2.57) | 1.53 (0.77–3.02) | 1.30 (0.80–2.12) | |||||||||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.004 | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.005 | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | <0.001 |

| Perforation | 2.09 (0.28–15.35) | 0.469 | 3.70 (0.89–15.45) | 0.073 | 1.49 (0.11–19.56) | 0.763 | 4.74 (1.71–13.09) | 0.003 | 0.88 (0.09–9.05) | 0.916 | ||

| Obstruction | 1.84 (0.88–3.85) | 0.104 | 1.42 (0.60–3.38) | 0.425 | 3.22 (1.67–6.19) | <0.001 | 2.95 (1.33–6.56) | 0.763 | 1.98 (1.21–3.24) | 0.007 | 1.79 (1.03–3.10) | 0.039 |

| Operation type | 0.094 | 0.167 | 0.865 | 0.199 | 0.292 | |||||||

| Open | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Laparoscopy | 1.91 (0.90–4.05) | 1.88 (0.77–4.62) | 0.93 (0.39–2.23) | 0.60 (0.27–1.31) | 0.61 (0.24–1.54) | |||||||

| Size (cm) | 1.05 (0.89–1.23) | 0.603 | 1.20 (1.05–1.38) | 0.008 | 1.19 (1.02–1.40) | 0.025 | 1.14 (1.03–1.27) | 0.014 | 1.21 (1.07–1.37) | 0.003 | ||

| Pathologic T stage | 0.304 | <0.001 | 0.377 | 0.002 | 0.637 | |||||||

| 3 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 4 | 1.74 (0.61–4.97) | 4.78 (2.23–10.22) | 1.37 (0.46–4.06) | 2.92 (1.48–5.74) | 1.24 (0.51–2.99) | |||||||

| Harvested LNs | 0.743 | 0.434 | 0.087 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| <12 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| ≥12 | 0.86 (0.35–2.10) | 0.74 (0.35–1.58) | 0.63 (0.37–1.07) | 0.37 (0.19–0.70) | ||||||||

| Lymphatic invasion | 2.78 (1.28–6.04) | 0.01 | 2.03 (0.79–5.26) | 0.143 | 1.87 (0.85–4.10) | 0.12 | 0.82 (0.30–2.22) | 0.692 | 1.87 (1.05–3.32) | 0.034 | 1.30 (0.66–2.56) | 0.454 |

| Venous invasion | 4.88(1.87–12.76) | 0.001 | 3.57 (1.15–11.06) | 0.028 | 6.70 (2.75–16.30) | <0.001 | 5.55 (2.04–15.06) | 0.001 | 3.51 (1.50–8.19) | 0.004 | 3.41 (1.38–8.42) | 0.008 |

| Perineural invasion | 4.05 (1.99–8.26) | <0.001 | 3.40 (1.47–7.85) | 0.004 | 3.75(1.91–7.34) | <0.001 | 2.34 (1.03–5.29) | 0.041 | 1.89 (1.07–3.34) | 0.028 | 1.33 (0.67–2.64) | 0.407 |

| Postoperative complication | 2.37 (0.97–5.79) | 0.057 | 2.03 (0.68–6.08) | 0.204 | 2.56 (1.11–5.90) | 0.027 | 2.02 (0.72–5.69) | 0.182 | 2.61 (1.35–5.05) | 0.004 | 1.56 (0.72–3.38) | 0.26 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.61 (0.77–3.36) | 0.206 | 0.79 (0.41–1.53) | 0.487 | 0.77 (0.48–1.26) | 0.301 | ||||||

†Multivariable analysis included factors with p-values < 0.20 in the univariable analysis.

HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification; CEA, preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level; LN, lymph node.

CSS

In a univariable analysis, age, BMI, obstruction, preoperative CEA level, tumor size, pathologic T stage, venous and perineural invasion and postoperative complications were identified as statistically significant factors affecting CSS. In a multivariable analysis, CEA (HR: 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00–1.01), tumor size (HR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.02–1.40) and venous (HR: 5.55, 95% CI: 2.04–15.06) and perineural invasion (HR: 2.34, 95% CI: 1.03–5.29) remained independent and significant factors affecting CSS (Table 3). Again, however, adjuvant chemotherapy was not statistically significant (HR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.41–1.53).

OS

In a univariable analysis, age, sex, BMI, ASA, pulmonary disease, perforation, obstruction, preoperative CEA level, tumor size, pathologic T stage, postoperative complications and lymphatic, venous and perineural invasion were identified as statistically significant. In a multivariable analysis, female sex (HR: 0.40, 95% CI: 0.21–0.73), pulmonary disease (HR: 3.02, 95% CI: 1.20–7.59), CEA (HR: 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.01), obstruction (HR: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.03–3.10), size (HR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.07–1.37), harvested LN ( > 12) (HR: 0.37, 95% CI: 0.19–0.70), and venous invasion (HR: 3.41, 95% CI: 1.38–8.42) were independent factors affecting OS (Table 3). However, adjuvant chemotherapy was not a statistically significant factor (HR: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.48–1.26).

Subgroup analysis

We further divided patients into low- and high-risk subgroups to analyze the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy. The high-risk subgroup was defined as patients who fulfilled one or more of the following criteria: poorly differentiated histology, perforation, bowel obstruction, < 12 examined LNs, lymphatic/vascular invasion, and perineural invasion. However, this factor did not affect RFS, CSS, or OS in either the low- or high-risk patient subgroups. A multivariable analysis revealed no significant factors (Table 4). Finally, we analyzed the factors affecting RFS, CSS and OS in the AC group. Notably, perineural invasion was an independent factor affecting RFS (HR: 5.03, 95% 1.89–13.40) and CSS (HR: 3.99, 95% CI 1.24–12.84), while obstruction and postoperative complications were associated with CSS (HR: 4.16, 95% CI: 1.22–14.14 and HR: 5.24, 95% CI: 1.33–20.61, respectively) and OS (HR: 2.74, 95% CI: 1.14–6.62 and HR: 3.35, 95% CI: 1.10–10.19, respectively) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on recurrence-free survival, cancer-specific survival and overall survival in patients with stage II colon cancer with low-risk and high-risk features.

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted HRa (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence-free survival | ||||

| Low risk | 0.921 | 0.497 | ||

| Surgery alone | Reference | Reference | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.93 (0.23–3.74) | 0.50 (0.07–3.63) | ||

| High risk | 0.165 | 0.143 | ||

| Surgery alone | Reference | Reference | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.88 (0.77–4.56) | 2.19 (0.77–6.25) | ||

| Cancer-specific survival | ||||

| Low risk | 0.095 | 0.528 | ||

| Surgery alone | Reference | Reference | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.38 (0.12–1.18) | 0.66 (0.18–2.44) | ||

| High risk | 0.608 | 0.942 | ||

| Surgery alone | Reference | Reference | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.25 (0.53–2.98) | 1.04 (0.35–3.07) | ||

| Overall survival | ||||

| Low risk | 0.054 | 0.364 | ||

| Surgery alone | Reference | Reference | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.49 (0.24–1.01) | 0.70 (0.32–1.52) | ||

| High risk | 0.722 | 0.649 | ||

| Surgery alone | Reference | Reference | ||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 1.13 (0.57–2.25) | 0.83 (0.36–1.89) | ||

aAdjusted factors: age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, cardiac disease, pulmonary disease, tumor side, preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level, operation type, tumor size, pathologic T stage and postoperative complication

FL, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 5.

Subgroup analysis for recurrence-free survival, cancer-specific survival and overall survival in adjuvant chemotherapy group.

| RFS | CSS | OS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable† | Univariable | Multivariable† | Univariable | Multivariable† | |||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (years) | 1.13 (0.99–1.29) | 0.067 | 1.06 (0.90–1.24) | 0.496 | 1.21 (1.04–1.40) | 0.014 | 1.14 (0.96–1.35) | 0.124 | 1.16 (1.03–1.31) | 0.015 | 1.12 (0.97–1.28) | 0.127 |

| Sex | 0.689 | 0.242 | 0.018 | 0.071 | ||||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| Female | 0.83 (0.34–2.04) | 0.51 (0.16–1.58) | 0.31 (0.12–0.82) | 0.39 (0.14–1.08) | ||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.09 (0.93–1.27) | 0.27 | 0.92 (0.75–1.13) | 0.42 | 0.97 (0.83–1.12) | 0.652 | ||||||

| ASA | 0.348 | 0.324 | 0.119 | 0.228 | ||||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||

| ≥2 | 1.80 (0.53–6.15) | 2.11 (0.48–9.28) | 2.59 (0.78–8.56) | 2.49 (0.57–10.93) | ||||||||

| Diabetes | 1.17 (0.43–3.23) | 0.757 | 0.65 (0.19–2.29) | 0.504 | 0.69 (0.28–1.69) | 0.41 | ||||||

| Hypertension | 1.53 (0.62–3.74) | 0.354 | 1.17 (0.43–3.17) | 0.757 | 1.64 (0.77–3.51) | 0.204 | ||||||

| Cardiac disease | 0.64 (0.09–4.76) | 0.66 | 0.05 (0.00–310.55) | 0.492 | 1.24 (0.29–5.25) | 0.769 | ||||||

| Pulmonary disease | 0.66 (0.09–4.91) | 0.683 | 1.11 (0.15–8.39) | 0.922 | 2.41 (0.83–6.99) | 0.105 | 5.28 (1.68–16.56) | 0.004 | ||||

| Tumor sideness | 0.889 | 0.514 | 0.518 | |||||||||

| Right sided | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Left sided | 1.07 (0.44–2.57) | 1.40 (0.51–3.86) | 1.28 (0.61–2.70) | |||||||||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.014 | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 0.249 | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.011 | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.092 |

| Perforation | 4.91 (0.66–36.78) | 0.122 | 5.59 (0.29–108.74) | 0.255 | 6.53 (0.84–50.82) | 0.073 | 5.97 (0.12–286.87) | 0.366 | 4.41 (0.58–33.36) | 0.151 | 1.83 (0.13–25.36) | 0.653 |

| Obstruction | 1.52 (0.58–3.96) | 0.391 | 3.38 (1.27–9.04) | 0.015 | 4.16 (1.22–14.14) | 0.022 | 2.29 (1.09–4.80) | 0.029 | 2.74 (1.14–6.62) | 0.025 | ||

| Operation type | 0.77 | 0.277 | 0.236 | |||||||||

| Open | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||||||||

| Laparoscopy | 1.16 (0.42–3.21) | 0.33 (0.04–2.46)) | 0.42 (0.10–1.77) | |||||||||

| Size (cm) | 1.09 (0.89–1.32) | 0.413 | 1.19 (0.96–1.48) | 0.113 | 0.94 (0.65–1.36) | 0.741 | 1.06 (0.89–1.25) | 0.514 | ||||

| Pathologic T stage | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Reference | 0.763 | Reference | 0.23 | Reference | 0.536 | ||||||

| 4 | 1.25 (0.29–5.40) | 2.49 (0.56–11.02) | 1.58 (0.37–6.71) | |||||||||

| Harvested LNs | ||||||||||||

| <12 | Reference | 0.296 | Reference | 0.141 | Reference | 0.4 | Reference | 0.006 | ||||

| ≥12 | 0.58 (0.21–1.60) | 0.45 (0.16–1.30) | 0.53 (0.12–2.35) | 0.35 (0.16–0.74) | ||||||||

| Lymphatic invasion | 2.47 (0.90–6.80) | 0.08 | 1.65 (0.47–5.77) | 0.43 | 3.13 (1.00–9.75) | 0.049 | 1.74 (0.35–8.63) | 0.499 | 3.04 (1.29–7.18) | 0.011 | 0.50 (0.19–1.31) | 0.157 |

| Venous invasion | 2.27 (0.53–9.79) | 0.271 | 3.64 (0.82–16.11) | 0.089 | 2.57 (0.37–17.99) | 0.341 | 1.49 (0.34–6.47) | 0.595 | ||||

| Perineural invasion | 4.45 (1.83–10.81) | 0.001 | 5.03 (1.89–13.40) | 0.001 | 4.24 (1.49–12.13) | 0.007 | 3.99 (1.24–12.84) | 0.02 | 2.72 (1.13–6.66) | 0.025 | 0.50 (0.20–1.26) | 0.142 |

| Postoperative complication | 2.57 (0.86–7.68) | 0.092 | 3.78 (1.21–11.85) | 0.023 | 5.24 (1.33–20.61) | 0.018 | 2.85 (1.07–7.61) | 0.036 | 3.35 (1.10–10.19) | 0.033 | ||

†Multivariable analysis included factors with p-values < 0.20 in the univariable analysis.

HR, Hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; ASA, The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification; CEA, Preoperative Carcinoembryonic Antigen level; LN, lymph node.

To evaluate the effect of adding oxaliplatin to 5-FU in elderly patients, we divided the patients who received chemotherapy into two groups: those who received 5-FU (n = 119) and those who received 5-FU and oxaliplatin (n = 22). There was no statistically significant difference in the 5-year RFS (86.5% vs. 70.2%, log-rank p = 0.111), CSS (90.2% vs. 87.9%, log-rank p = 0.743), or OS (86.3% vs. 87.9%, log-rank p = 0.816) between the two groups. Moreover, adding oxaliplatin did not significantly affect the RFS (HR 2.24, 95% CI 0.81–6.62), CSS (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.20–3.60), or OS (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.20–3.60).

Discussion

Our study shows that postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy confers no major survival benefit in patients older than 70 years with stage II colon cancer, even after propensity score matching. Additionally, adjuvant chemotherapy did not affect the RFS, CSS, or OS outcomes even in patients with high-risk features. These findings may have a positive impact on many patients, especially those at an advanced age, who can avoid the problems associated with chemotherapy.

As noted previously, no consensus has been reached regarding the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. The QUASAR trial reported improved survival outcomes in patients with stage II colon cancer who received chemotherapy comprising FU and folinic acid9, while Casadaban et al. reported better OS in patients with stage II colon cancer included in a national cancer database8. However, recent studies including elderly patients, in contrast to the QUASAR trial and the study by Casadaban et al., have failed to demonstrate an effect of adjuvant chemotherapy. For example, Booth et al. reported no benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in terms of CSS and OS even in high-risk patients in a population-based study14, consistent with our findings. These results suggest that management guidelines for stage II patients should be redefined.

There is some debate about the role of chemotherapy in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. The Adjuvant Colon Cancer End Points Collaborative Group showed that elderly patients (aged ≥70 years) with stage II/III colon cancer did not experience a statistically significant benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in terms of disease-free survival (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.19) and OS (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.95 to 1.23)15. Popescu et al., in their study of first-line chemotherapy for patients with advanced colorectal cancer in elderly patients (≥70), reported that the median OS period was shorter in the elderly group than in younger patients (292 vs. 350 days, p = 0.04)16. Strowitzki et al. showed that even in a total of 468 patients with colorectal liver metastases the administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is of questionable value17.

However, there are authors who have shown positive effects of chemotherapy on elderly patients. Fata et al. reported that elderly patients with stage II/III colon cancer benefit from 5-FU-based adjuvant therapy, without a significant increase in toxicity compared to that in their younger counterparts18. There is even an article about the benefit of adjuvant therapy after curative resection in stage IV colon cancer. Rahbari et al. analysed a total of 297 patients with curative resection of colorectal cancer liver metastasis. According to their results, adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with improved survival in the entire cohort (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.69–0.98)19.

Some studies have evaluated the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy, particularly in patients older than 70 years with stage II colon cancer. For example, Tsai et al. reported no significant difference in OS between patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy and those without adjuvant chemotherapy6. However, that study compared two groups, adjuvant chemotherapy vs. no adjuvant chemotherapy, that were unbalanced in terms of baseline characteristics such that the former group had a worse pathologic grade and larger proportion of pT4 stage disease. In a large Korean database study20, Kim et al. performed a subgroup analysis of patients older than 70 years with stage II colon cancer and concluded that adjuvant chemotherapy yielded an OS benefit. However, Kim and colleagues also reported that their two groups were unbalanced in terms of baseline characteristics, and limitations of their dataset precluded analyses of RFS and CSS. By contrast, we performed propensity score matching to balance the study groups and conducted analyses of both RFS and CSS. These represent strengths of our study.

In our multivariable analysis of patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy, we identified perineural invasion, a well-known prognostic factor for stage II colon cancer13, as a statistically independent factor affecting RFS and CSS. Furthermore, CEA and tumour size also affected CSS and OS in multivariable analysis. A higher pretreatment CEA level has been identified as a predictor of RFS and OS21–23. In particular, an elevated CEA level preoperatively in early stage colon cancer has been associated with a poor prognosis compared with normal CEA levels in a node-positive tumour24. Tumour size is also a factor associated with a poor oncologic prognosis25,26.

We further identified obstruction and postoperative complications as significant factors affecting CSS and OS and confirmed a lack of covariance between these factors (χ2-test, p > 0.999. We note that patients with obstruction had a lower BMI, compared to those without obstruction (21.6 vs. 23.1 kg/m2, p = 0.004), which indicates the need for careful attention to avoid postoperative complications during chemotherapy in fragile patients. Furthermore, a lower BMI is always associated with a worse condition. We recommend further study of cancer-related mortality after chemotherapy.

To our best knowledge, our study is first study of its type to apply propensity score matching to balance patient groups even with respect to co-morbidity. Our findings were consistent with other recent studies that found no difference in the oncologic outcomes of patients with stage II colon cancer who did and did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Taken together, these findings underscore the need to discuss guidelines for the management of geriatric patients with stage II colon cancer.

Limitations

This study had some potential limitations. First, the retrospective design might have led to selection bias. Second, we were unable to obtain information about patients who received chemotherapy at a reduced dose or cycle number. Third, we included a relatively small number of patients, compared to other studies based on national databases. However, the total number of initially included patients was not small, and the 290 patients remaining after propensity score matching was sufficient for a statistical analysis. Fourth, we lacked data regarding why chemotherapy was not given to some patients, even in the high-risk subgroup. Although we were limited by an inability to confirm the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, we attempted to eliminate differences in confirmed comorbidities between the two groups as much as possible. Fifth, in the medical records, there was no information about resection margin status, such as intermediate or close margin, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline13, although information about other high-risk features was present. Our study only included patients who underwent curative resection (R0). For this reason, there were no patients with a positive margin.

Conclusion

Adjuvant chemotherapy did not appear to confer RFS, CSS, or OS benefits in patients older than 70 years with stage II colon cancer. However, our finding that obstructive colon cancer and postoperative complications were associated with poorer survival outcomes suggests that patients meeting these criteria should be followed cautiously during chemotherapy. Our findings underscore the need to revise guidelines for the treatment of stage II colon cancer. As our study population is not representative of all patients with stage II disease, we believe that a well-balanced, large population-based study is warranted.

Author Contributions

Kil-yong Lee, Min Jung Kim, and Ji Won Park analyzed and interpreted the data. Ki-young Lee, Sangsik Cho and Yoon-Hye Kwon collected the data. Ji Won Park, Seung-Bum Ryoo, Seung-Yong Jeong and Kyu Joo Park performed the operation and followed the patients. Kil-yong Lee was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

Kil-yong Lee, Ji Won Park, Ki-young Lee, Sangsik Cho, Yoon-Hye Kwon, Min Jung Kim, Seung-Bum Ryoo, Seung-Yong Jeong and Kyu Joo Park have no conflicts of interest or financial ties.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Center MM, Jemal A, Ward E. International Trends in Colorectal Cancer Incidence Rates. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2009;18(6):1688–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. New Engl J Med. 1999;30(341(27)):2061–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nitsche U, Stoss C, Friess H. Effect of Adjuvant Chemotherapy on Elderly Colorectal Cancer Patients: Lack of Evidence. Gastrointest Tumors. 2017;4(1-2):11–9. doi: 10.1159/000479318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao H, et al. Adherence to Treatment Guidelines and Survival for Older Patients With Stage II or III Colon Cancer in Texas From 2001 Through 2011. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2018;15(124(4)):679–87. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong L, Ahn C, Symanski E, Lai D, Du XL. Effects of newly developed chemotherapy regimens, comorbidities, chemotherapy-related toxicities on the changing patterns of the leading causes of death in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(6):1234–42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai TC, et al. Survival of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Among Elderly Patients with Stage II Colon Cancer. Int J Gerontol. 2018;12(2):94–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijge.2017.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andre T, et al. Improved Overall Survival With Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin As Adjuvant Treatment in Stage II or III Colon Cancer in the MOSAIC Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;1(27(19)):3109–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casadaban L, et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Is Associated With Improved Survival in Patients With Stage II Colon. Cancer. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2016;1(122(21)):3277–87. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray R, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Lancet. 2007;15(370(9604)):2020–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61866-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verhoeff SR, van Erning FN, Lemmens VEPP, de Wilt JHW, Pruijt JFM. Adjuvant chemotherapy is not associated with improved survival for all high-risk factors in stage II colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 2016;1(139(1)):187–93. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A, et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Use and Outcomes of Patients With High-Risk Versus Low-Risk Stage II Colon. Cancer. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2015;15(121(4)):527–34. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis C, Xun PC, He K. Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on recurrence, survival, and quality of life in stage II colon cancer patients: a 24-month follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(4):1463–71. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2931-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benson AB, 3rd, et al. Colon Cancer, Version 1.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(3):370–98. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Booth CM, et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage II Colon Cancer: Practice Patterns and Effectiveness in the General Population. Clin Oncol-Uk. 2017;29(1):E29–E38. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCleary NJ, et al. Impact of age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in patients with stage II/III colon cancer: findings from the ACCENT database. J Clin Oncol. 2013;10(31(20)):2600–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popescu RA, Norman A, Ross PJ, Parikh B, Cunningham D. Adjuvant or palliative chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in patients 70 years or older. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2412–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strowitzki MJ, et al. Influence of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on resection of primary colorectal liver metastases: A propensity score analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116(2):149–58. doi: 10.1002/jso.24631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fata F, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with colon carcinoma: a 10-year experience of the Geisinger Medical Center. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2002;1(94(7)):1931–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahbari NN, et al. Adjuvant therapy after resection of colorectal liver metastases: the predictive value of the MSKCC clinical risk score in the era of modern chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2014;11:14–174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim MK, et al. Effect of Adjuvant Chemotherapy on Stage II Colon Cancer: Analysis of Korean National Data. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50(4):1149–63. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takagawa R, et al. Preoperative Serum Carcinoembryonic Antigen Level as a Predictive Factor of Recurrence After Curative Resection of Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(12):3433–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang WS, et al. Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level as an independent prognostic factor in colorectal cancer: Taiwan experience. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30(1):12–6. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyd003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiratkapun S, Kraemer M, Seow-Choen F, Ho YH, Eu KW. High preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen predicts metastatic recurrence in potentially curative colonic cancer: results of a five-year study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(2):231–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02234298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thirunavukarasu P, et al. Effect of Incorporation of Pretreatment Serum Carcinoembryonic Antigen Levels Into AJCC Staging for Colon Cancer on 5-Year Survival. Jama Surg. 2015;150(8):747–55. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kornprat P, et al. Value of Tumor Size as a Prognostic Variable in Colorectal Cancer A Critical Reappraisal. Am J Clin Oncol-Canc. 2011;34(1):43–9. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181cae8dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saha, S. et al. Tumor size as a prognostic factor for patients with colon cancer undergoing sentinel lymph node mapping and conventional surgery. J Clin Oncol. 1;31(4) (2013).