Abstract

The development of neuroprotective therapies is a sought-after goal. By screening combinatorial chemical libraries using in vitro assays, we identified the small molecule BN201 that promotes the survival of cultured neural cells when subjected to oxidative stress or when deprived of trophic factors. Moreover, BN201 promotes neuronal differentiation, the differentiation of precursor cells to mature oligodendrocytes in vitro, and the myelination of new axons. BN201 modulates several kinases participating in the insulin growth factor 1 pathway including serum–glucocorticoid kinase and midkine, inducing the phosphorylation of NDRG1 and the translocation of the transcription factor Foxo3 to the cytoplasm. In vivo, BN201 prevents axonal and neuronal loss, and it promotes remyelination in models of multiple sclerosis, chemically induced demyelination, and glaucoma. In summary, we provide a new promising strategy to promote neuroaxonal survival and remyelination, potentially preventing disability in brain diseases.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13311-019-00717-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Words: Neuroprotection, neuroinflammation, neurodegenerative diseases, multiple sclerosis, glaucoma

Introduction

Brain diseases represent a significant clinical challenge due to the known sensitivity of the central nervous system (CNS) to damage and its limited capacity for repair and regeneration. Brain injury and brain diseases are notorious for significant long-term disability [1, 2]. After insult, damage to neurons and axons may induce several forms of neuropathology including necrosis, apoptosis, autophagia, necroptosis, and pyroptosis. Further, brain injury may disrupt the connections between neurons, as what occurs following axon degeneration (anterograde or Wallerian degeneration, retrograde degeneration or dying-back, or even transynaptic degeneration), synaptic loss, or dendritic pruning [3–5]. Although some of these processes take place early after insult, others may be delayed for weeks, months, or even years. For these reasons, the discovery of agents that promote neuroprotection is a health priority.

In multiple sclerosis (MS), the autoimmune attack and chronic inflammation produces a massive destruction of myelin, with loss of oligodendrocytes and their precursors in the long term, as well as relative axonal loss. Long-term disability is mainly dependent on axonal loss, which is the result of the acute inflammatory damage and degeneration of chronically demyelinated axons. Because current immunotherapy decreases the frequency of autoimmune attacks but chronic inflammation persists, neuroprotection is being pursued as combination therapy to prevent high levels of disability [6]. On the other hand, glaucoma is a neurodegenerative disease of the visual pathway, with high intraocular pressure being 1 of the most common predisposing factors and the only 1 targeted with approved therapies. However, in most cases, even though treated with ocular pressure-lowering drugs, the disease keeps progressing, and for this reason, neuroprotection is defined as a high priority for preventing blindness due to this condition [7].

In order to develop new therapies for prevention of brain damage [1–6], we screened combinatorial libraries of small chemicals in order to identify compounds that favor the survival or differentiation of neuronal precursors and the survival of mature and immature neurons in the presence of stressors (including oxidative stress or trophic factor deprivation). We also assessed the capacity of such compounds to promote the survival and differentiation of myelin-forming cells. The screening included in vitro cell assays and in vivo models of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. We describe the small chemical BN201 that displays an array of neuroprotective effects in neurons and myelin-forming cells, and is being developed at present as a neuroprotective therapy for MS and optic neuritis (NCT03630497).

Material and Methods

Chemical Libraries

Two different chemical libraries developed at the Institute of Medical Advanced Chemistry of Catalonia, CSIC, Barcelona, Spain (Prof Angel Messeguer), were tested: first, N-alkylglycine trimers (peptoids), and second, cyclic tetralkylammonium salts. The cyclic tetraalkylammonium salts library was composed of 66 master compounds (44 compounds contained a 6-membered ring, whereas 22 contained a 7-membered ring) [8]. The peptoid (oligomers of N-alkylglycine units) library consisted of controlled mixtures constructed under the positional scanning format, and it was composed by 5120 compounds [9, 10]. The lyophilized compounds were dissolved in H2O with 5% DMSO for the in vitro assays and were tested in controlled mixtures at 1 to 5 mg/ml.

Cell Lines

All cell lines were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and were tested and controlled for a number of expansion cycles. All in vitro experiments were repeated twice.

PC12 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 15% horse serum (HS), and penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). The SH-SY5Y cell line was maintained in 50% Ham’s F12 medium and 50% Earle’s minimal essential medium, supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1% P/S. The NSC-34 cell line was cultivated in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. The rat Schwannoma RN22 cell line was cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and P/S. All the cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and they were grown in 60 and 100 mm tissue culture dishes (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

PC12 Differentiation Assay

PC12 cell differentiation and survival was measured by plating cells onto collagen-coated 24-well plates and adding NGF (100 ng/ml, [11]) or the small chemicals to the cultures at different concentrations (2-20-100 ng/ml and 2-20-50 μg/ml) (see additional details in Fig. S1). The number of differentiated cells with neurite processes greater than 2 cell bodies in length were counted after 5 days of treatment, counting 100 cells in 3 randomly selected fields in each well (at least 300 cells were assessed at random in each experiment) [11].

In Vitro Oxidative Stress Survival Assays

RN22 cells were plated in 24-well plates (20,000 cells/well) in DMEM alone and after allowing the cells to adhere for 3 days, and copper sulfate (CuSO4, 150 μM) was added in the presence or absence of NGF (100 ng/ml) or BN201 (1-10-50 ng/ml or 1-10 μg/ml [12]. After 24 h, cell viability was studied by determining the amount of MTT (Sigma, St Louis, MI, USA) that was reduced to insoluble purple formazan. After removing the medium, the water-insoluble formazan was solubilized in DMSO (Sigma) and the dissolved material was measured on a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 570 nm, subtracting the background at 650 nm.

Human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were first differentiated to a neuronal phenotype with retinoic acid (10 μM) for 6 days and they were then pretreated for 3 days with BN201 at different doses (0.03, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 3, 5, 10, 20, and 100 μM) in fresh medium, with or without K252a (200 nM). MPP+ (100 μM) or H2O2 (100 μM) was then added after 30 min and the number of surviving cells was determined by quantifying the MTT staining 48 h later as described above [13, 14].

Trophic Factor Deprivation In Vitro Assay

NSC-34 cells were seeded in 24-well poly-lysine-coated plates (30,000 cells/well) and preincubated for 24 h in DMEM plus 10% FBS with various doses of BN201 (0.2, 0.1, 2, 20, and 50 μg/ml), or with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) (2 μg/ml) or brain-derived trophic factor (BDNF) (20 ng/ml) as positive controls [15]. The medium was then removed and replaced with fresh DMEM without FBS, and after 48 h, cell viability was assayed by the MTT assay.

In Vitro Remyelination Assays

Purified retinal ganglion cells (4000/well) from P7 rats were cultured in 96-well plates for 10 days in culture media in order to produce newly generated axons. Then, oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) (Olig2+) from P8 rats were plated on top of the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), and stimulus was added, including placebo (5% DMSO), positive control (gamma secretase inhibitor DAPT (2,4-diamino-5-phenylthiazole) (1 μM)) [16], and increasing concentrations of BN201 (0.05, 0.13, 0.41, 1.2, 3.7, 11, 33, and 100 μM). OPCs were allowed to maturate for 6 days, and by the end of the experiments, cultures were stained with anti-MBP antibody. Automatic microscopy quantification was performed assessing the percentage of differentiated oligodendrocytes (OLs) and percentage of myelinating OLs wrapping RGC axons (defined as the presence of linear myelin basic protein (MBP+) structures) [17]. Quantification was done with the GE InCell software, with custom morphological analyses written at the Myelin Repair Foundation to identify and quantify the stringy morphology in mature OLs/MBP staining denoting axonal alignment. Assays were performed in duplicate and repeated twice.

Binding Assays

Binding assays were performed using the KINOMEscan for kinases, the tkMAX Biosensor Panel for tyrosine kinase receptors (RTKs), and the GPCRmax panel for G protein receptors (all from DiscoverX, Freemont, CA, USA) and the CNS Receptor Express profile (CEREP, Celle l’Evescault, France). BN201 was tested at 10 μM. The KINOME tested 456 human kinases and the tkMAX scans tested 19 RTK. The results are expressed as percentage relative to the Control (Ctr). Values of % Ctr higher than 35 are not considered as relevant binding.

The GPCRmax panel uses the PathHunter β-arrestin assay that monitors the activation of a G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) using the enzyme fragment complementation (EFC) with β-galactosidase (β-Gal) as the functional reporter. Compound activity was analyzed using CBIS data analysis suite (ChemInnovation, San Diego, CA). For agonist mode assays, percentage activity was calculated using the following formula: % Activity = 100% × (mean RLU of test sample − mean RLU of vehicle control) / (mean MAX control ligand − mean RLU of vehicle control). For antagonist mode assays, percentage inhibition was calculated using the following formula: % Inhibition = 100% × (1 − (mean RLU of test sample − mean RLU of vehicle control) / (mean RLU of EC80 control − mean RLU of vehicle control)).

The CNS receptor assay is based in the binding to a radioactively labeled CNS receptor. Compound binding was calculated as percentage inhibition of the binding of a radioactively labeled ligand specific for each target. Results showing an inhibition or stimulation higher than 50% are considered to represent significant effects of the test compounds.

The CETSA assay was conducted by Pelago Biosciences Inc. (Solna, Sweden) in the SH-S5Y5 cell line.

Western Blot Phosphorylation Assays

Subconfluent cells (SH-SY5Y or Hela cells) were grown overnight in medium containing 2% FBS and 1% HS, and they were stimulated with BN201 at 2 doses (10 and 100 μM) and time points (0.5, 1, and 4 h). Cells were then washed with cold PBS and briefly sonicated in RIPA buffer with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Lysates (20 μg of total proteins) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman, Dassel, Germany). After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/0.2% Tween 20), the membranes were probed overnight at 4 °C with specific antibodies against phosphorylated proteins: p-NDRG1 (Thr346, 1/1000, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), p-Tau (pSer214, 1/700, Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA), p-Nedd4-2 (S448, 1/1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), p-GSK3b (Ser9, 1/1000, Cell Signaling), and p-Foxo3 (Ser253, 1/700, Abcam). Staining with anti-glyceraldehyde-3phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) monoclonal antibody (1/5000, Chemicon, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) was used as reference. The membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated IgG (Cell Signaling) for 2 h at room temperature, and the phosphorylated species were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and quantified.

Cytometry Phosphorylation Assays

Phosphorylation of AKT and p70S6K was assessed in the SH-SY5Y cell lines using the Millipore’s FlowCellect PI3K-mTOR Signaling Cascade Mapping Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA, FCCS025210) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

SGK Blocking Assays

Blocking of SGK2 activity was assessed by inhibiting SGK2 expression using iRNA (Dharmacon Accell siRNA assay: #E-004673-00-0005, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) (see Fig. S2) [18] or blocking its kinase activity using the SGK-1/2 inhibitor GSK650394 (Tocris Biosciences, Bristol, UK: catalog # 3572; 2 μM) [19]. Dexamethasone (1 μM) was used as a positive control.

In Vivo Studies in Models of MS and Glaucoma

All experiments were repeated twice, all trials included 10 animals per arm, and animals were randomly assigned to each group and therapies were administered in a blinded manner (evaluator was not aware of the treatment group). As placebo, we used the same solution in which BN201 was dissolved (physiological saline solution plus 5% DMSO). Therapy was started after disease onset: in the experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) model, therapy started after animals showed clinical signs; in the chemical demyelination model, therapy started 1 h after lysolecithin challenge; and in the glaucoma model, therapy started 1 week after induction of ocular hypertension. All animal studies were approved by the University of Barcelona Committee on Animal Care.

Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis

Female C57BL/6 mice from Harlan (8-12 weeks old) were immunized subcutaneously in both hind pads with 300 μg of a myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35-55, Spikem, Florence, Italy) emulsified with 50 μg of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (H37Ra strain; Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) as described previously [20]. Mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with Pertussis toxin (500 ng, Sigma) at the time of immunization and 2 days later. The animals were weighed and inspected for clinical signs of disease on a daily basis by an observer blind to the treatments. The severity of EAE was assessed on the following scale: 0 = normal; 0.5 = mild limp tail; 1 = limp tail; 2 = mild paraparesis of the hind limbs, unsteady gait; 3 = moderate paraparesis, voluntary movements still possible; 4 = paraplegia or tetraparesis; 5 = moribund state; 6 = death [21]. Therapy always started after disease onset, when animals reached an EAE clinical score > 1.0. Animals were randomized to each treatment after reaching such score and the clinical score was assessed blindly. Clinical assessment extended for 30 days after randomization in order to cover the early inflammatory and late inflammatory/degenerative phases. Considering that on average animals reached the clinical score to start therapy by day 12, clinical follow-up was used to expand until day 40 (depending on each animal). Pathology was done always in the last day of the clinical assessment.

At the end of the study, mice were anesthetized and perfused intracardially with 4% of paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.6). The brain, spinal cord, optic nerve, and retina of the animals were dissected out and fixed or frozen until use; the spleen was collected for retrieving immune cells; and serum was obtained from all animals included in the study. Slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Luxol fast blue (LFB), and Bielschowsky’s silver impregnation (BSI) to assess inflammation, demyelination, and axonal pathology. Pathology quantification was conducted in the optic nerve and spinal cords because of the relevance of such tracts in MS disease; in addition, their longitudinal anatomy allowed more systematic quantification. Quantification of axonal loss was performed with BSI slides and using the following scoring: 0, normal staining of axons; 0.5, traces of perivascular or subpial axonal loss; 1, marked perivascular or subpial axonal loss; 2, confluent perivascular or subpial axonal loss; 3, massive confluent axonal loss; and 4, extensive axonal loss. Semiquantitative histological evaluation of the inflammation and demyelination was scored blind to the treatment using the following scale: 0 = normal; 1 = 1 to 3/section perivascular cuffs with minimal demyelination; 2 = 3 to 10 perivascular cuffs/section accompanied by moderate demyelination; and 3 = widespread perivascular cuffing, extensive demyelination with large confluent lesions [22].

Animals were given daily intraperitoneal injection of BN201 (12.5-100 mg/kg), glatiramer acetate (GA) (5 mg/kg [23], from Teva Pharmaceuticals, Petah Tikva, Israel), or oral gavage of dimethyl fumarate (DMF) (15 mg/kg [24], from Sigma) or fingolimod (FTY, 2 mg/kg [25], from Selleck Chemicals, Munich, Germany) or the neurotrophin mimetics gambogic amide (2 mg/kg [26], from Sigma) or xaliproden (SR57746A, at 10 mg/kg [27], from Tocris, Bristol, UK), or placebo (physiological saline solution plus 5% DMSO). All drugs were as prepared in water with 5% DMSO.

Passive Transfer EAE

MOG35-55-specific Th17 cell passive transfer EAE in C57BL6 mice was performed as previously described [28]. Animals were treated with BN201 (25 and 50 mg/kg daily) or placebo after immunization. Splenocytes and lymph nodes were collected by day 12 (post-immunization) and restimulated in vitro with MOG35-55 and rmIL23 for 3 days and then infused (intravenously) to recipient animals. Recipient animals (15 per group) were treated with BN201 (25 or 50 mg/kg daily) or placebo for 30 days. Clinical score was recorded as described above.

Lysolecithin Induced Chemical Demyelination of the Optic Nerve

Chemical demyelination of the optic nerve in Sprague-Dawley rats (male, 7-8 weeks old, 250-300 g) was induced with lysolecithin as described elsewhere [29]. After exposing the optic nerve from a random eye, Evans Blue dye (2 μl) was placed under the dura mater to show the microinjection site in order to identify the focal lesion for the histology. Microinjections were performed with a Hamilton syringe inserted into the optic nerve as superficially as possible at 2 mm posterior to the globe and 0.8 μl of 1% lysolecithin (with 0.02% Evans Blue) was slowly pressure-injected onto the nerve for approximately 30 s. Sham control rats were injected with 0.02% Evans Blue in 0.8 μl saline.

BN201 was tested at saturating doses (50 and 100 mg/kg in mice correspond to 35 and 70 mg/kg in rats). All formulations were prepared daily and dosed immediately for 6 days (days 0-5). The first dosage was given 1 h after lysolecithin injection (curative treatment) and repeated once/day until the end of the experiment (last treatment on day 5), and animals were subsequently sacrificed on day 6 (24 h after the last treatment dose). Optic nerves (from globe to chiasm) and eye were removed and were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde overnight. Five-micrometer-thick (5 μm) paraffinated transverse sections were made at the site of injections (at the place of the dye). Serial sections of each optic nerve were obtained (6 sections). Histological stain and quantification was performed as explained above.

In Vivo Intraocular Hypertension Model of Glaucoma

Sprague-Dawley rats (4 months old) were anesthetized with isobutane, and hypertonic saline solution was injected into the episcleral vein of the right eye. Intraocular pressure was measured before the operation and it was monitored once weekly using the TonoLab tonometer over 7 weeks. Topical application of BN201 (200 and 400 μg/ml) or timolol (200 μg/ml) eye drops began 1 week after the induction of intraocular hypertension. NGF was used as a positive control (200 μg/ml) and physiological solution was used as a placebo, and the left eye was used as a control without glaucoma. Seven weeks after glaucoma induction, the animals were sacrificed by overdose of anesthesia and their eyes were fixed in 4% PFA. Subsequently, paraffin sections of the eyes (20 μm) were used for histological quantification (H&E) and the number of RGCs was counted in 10 different fields for each eye.

Cerebellar Organotypic Culture Model of Neuroinflammation

The model of neuroinflammation using cerebellar organotypic cultures stimulated with LPS has been described previously [30]. Briefly, cerebellum slices from P8 mice (400 μm) were plated in 6-well plates (3 slices/well) containing a 30-mm culture plate insert with 0.4 μm pores (Millipore) in 1 ml full culture medium (5% CO2 in 50% basal medium with Earle’s salt, 25% Hank’s buffered salt solution, 25% inactivated HS, 5 mg/ml glucose, 0.25 mM L-glutamine, and 25 μg/ml P/S) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. All experiments were performed after 1 week in culture, replacing the medium in each well and adding BN201 (100 ng/ml) or a placebo (physiological solution) for 1 h prior to the LPS challenge (15 μg/ml). The slices and culture supernatants were recovered at different time points: 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. At each time point, we obtained untreated control slices, LPS/placebo-treated slices, and a LPS/BN201-treated slices from 3 different experiments. RNA extraction was obtained by freezing the slices directly at − 20 °C in RNA Lysis Buffer (Qiagen, Chatworth, CA). In another 3 experiments, slices were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy after fixation in 4% PFA for 45 min at room temperature. Culture supernatants were stored at − 20 °C and used for measuring TNFα by ELISA and iNOS gene expression by PCR. The q-ratio of myelin was measured from electron microscopy images as explained elsewhere [31].

Immunohistochemistry in Rodent’s Brain

Immunohistochemical procedures were performed on 10 μm paraffin-embedded sections of brain and spinal cord as described previously [22]. Primary antibodies were added at the following concentrations: anti-Foxo3a antibody (1/100; Bethyl Labs, Montgomery, TX), anti-iNOS antibody (1:200, Abcam), anti-CD86 antibody (1:200, Abcam), anti-arginase-1 antibody (1:200, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), and anti-CD206 antibody (1:1000, Abcam). The secondary fluorescence antibodies were as follows: anti-goat 633 (1:200, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), anti-rat 488 (1:200, Molecular Probes), and anti-rabbit 488 (1:200, Fluoprobes, Interchim, San Diego, CA). Immunohistochemical findings were quantified using Fiji software. The specificity of the immunoreaction was determined by incubating sections without the primary antibodies or using the corresponding isotype controls which yielded no immunoreactivity.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Brains, spinal cords, and organotypic cultures were homogenized in RNA lysis buffer (Qiagen) and the total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), including a RNase-Free DNase treatment (Qiagen). Total RNA (35 μg) was reverse transcribed at 37 °C for 2 h after an initial incubation at 25 °C for 10 min using the Reverse Transcription System (High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). For RT-PCR, primers and target-specific fluorescence-labeled TaqMan probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems (TaqMan Gene Expression assays), and we used the TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Amplification of complementary DNA was performed on a DNA Engine Opticon 2 Real-Time System (MJ Research, Watertown, MA) using 0.9 μM of each primer, 0.25 μM of the probes, and 20 ng complementary DNA. The reaction conditions were an initial 2 min at 50 °C, followed by 10 min at 95 °C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. Each sample was run in triplicate, and in each plate, the target and the endogenous control were amplified in different wells. The expression of the gene tested was quantified relative to the level of the housekeeping gene 18S RNA, as explained previously [32].

Foxo3 Translocation Assessed by Immunofluorescence in CNS Tissue

The brain of the mice was removed and dissected into 3 parts (anterior, medial, and posterior part), and 3 coronal cross-sections of each part of the brain were obtained (4 μm slices). The spinal cord was also cut into 3 parts (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar), and 3 cross-sections of the lumbar spinal cord (4 μm slices) were mounted for observation. The brain and spinal cord were stained with the primary anti-Foxo3a antibody (1/100; Bethyl Labs), which was detected with a secondary anti-rabbit Cy3 antibody. The study focused on the gray matter as the region where the majority of neuron’s somas lie. Quantification was performed at × 20 augmentation as the number of DAPI-stained nucleus without overlapping Cy3 stain, with the Cy3 stain (Foxo3) being located in the cytoplasm per section (cells with translocation) per 106 cells. Representative images were taken at × 100 magnification on an ApoTome.2 Zeiss microscope [33].

Immunological Assays in Splenocytes from EAE Mice

Proliferation assays were conducted in splenocytes from immunized C57BL/6 mice participating in the dose–response study (Fig. 3A) and collected by day 12 after immunization. Proliferation assays were based on [H3] thymidine incorporation, as described previously [34]. Cytokine analysis (interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-17, and interferon γ (IFNγ)) was done in the supernatants of cultures by ELISA following the manufacturer’s instructions (ELISA kits Ready-SET-Go by eBiosciences, Affimetrix, Santa Clara, CA).

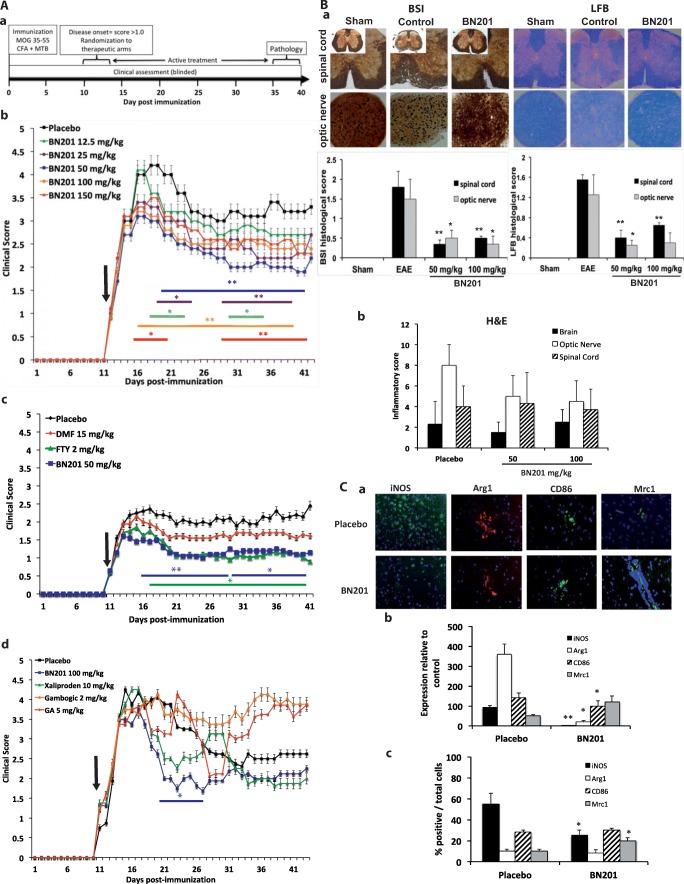

Fig. 3.

In vivo effects of BN201 in animal models of neuroinflammation. (A–C–D) Experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE) was induced in C57BL6 mice immunized with MOG35-55. Animals were treated after disease onset after randomization and scores were collected blinded. Dose selection is indicated in the methods and the placebo was the BN201’s dissolving solution (5% DMSO in saline). Results are representative from 2 experiments comprising 10 animals per group for each study. Results are shown as the mean of the clinical score per day. Arrow indicates the day therapy started. Lines in color indicate the days the clinical score was significantly different with respect to the placebo group (Mann–Whitney test day by day, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01). A EAE curative trials: (a) study design; (b) clinical score (mean and SEM) in animals treated with increasing doses of BN201 (12.5, 25, 50, 100, 150 mg/kg, i.p.); (c) compared with immunomodulatory drugs fingolimod (FTY, 2 mg/kg) and dimethyl fumarate (DMF, 15 mg/kg); (d) compared with the neurotrophin mimetics xaliproden (910 mg/kg), gambogic acid (2 mg/kg), and glatiramer acetate (GA 5 mg/kg). B Histological analysis of the effects of BN201 in the EAE model by the end of the follow-up (day 30 after randomization): (a) 3 animals per group were analyzed at the levels of the optic nerve and spinal cord assessing axonal density with the Bielschowsky’s silver impregnation (BSI) and myelin preservation with the Luxol fast blue stain (LFB); (b) inflammatory infiltrates by hematoxylin–eosin stain (H&E). Graphs show the histological score in the sham (nonimmunized), placebo (EAE), and animals treated with BN201 (50 and 100 mg/kg). C Microglia profile in the brain of EAE animals treated with BN201 was assessed at the end of the experiment, by quantifying gene expression and protein levels for iNOS, CD86, arginase, and the mannose receptor (Mrc1 or CD206). (a) Representative microphotograhs of the immunofluorescence stains; (b) mRNA levels by PCR; (c) protein levels by Western blot as the percentage of cells expressing the protein. Results are shown as the mean + SEM and a representative image of protein immunostaining. D Peripheral immune response in EAE animals treated with BN201 from the experiment shown in (Aa). Graphs shows (a) cell proliferation (counts per million (cpm)) and cytokine levels of (b) IL-2, (c) IL-10, (d) IL-4, (e) IFNγ, and (f) IL-17. Assays were carried out in splenocytes obtained by day 12 after immunization from animals suffering EAE and treated with placebo (EAE placebo) or BN201 100 μg/ml/day (EAE BN201). Sham indicates assays from nonimmunized animals. Splenocytes were restimulated in vitro with MOG35-55 alone or combined with BN201 100 μM or saline (control). Results are shown as the mean + SEM. Statistical significance refers to BN201-treated animals compared with placebo EAE animals; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. E Effects of BN201 in the in vitro model of neuroinflammation using cerebellar cultures challenged with LPS. Experiments were performed twice. (a) Culture microphotographs treated with BN201 (10 μM) showed less demyelination (MBP stain) and axonal loss (NFL stain) than placebo; (b) quantification of cerebellar culture demyelination (MBP stain) and axonal loss (NFL stain); (c) g-ratios of individual axons as a function of axonal diameter (g-ratios were analyzed from transmission electron microscopic images) in placebo and BN201-treated cultures. Cultures challenged with LPS and treated with BN201 showed lower levels of: (d) TNFα measured by ELISA or (e) iNOS gene expression measured by PCR, than placebo (LPS group). *p < 0.05

Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay

Parallel artificial membrane permeability assay was used as an in vitro model of passive blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability [35]. An artificial membrane immobilized on a filter was placed between a donor and an acceptor compartment. After BN201 was introduced into the donor compartment and following a permeation period (18 h), its concentration in the donor and acceptor compartments was measured on a UV spectroscopy reader. The compound stock solutions were diluted 200-fold in a universal buffer at pH 7.4 and added to the donor wells. The filter membrane was coated with porcine brain lipid in dodecane and the acceptor well was filled with pH 7.4 buffer. The effective permeability (Pe) of the compounds was calculated with the pION PSR4p software. Samples were analyzed in triplicate and the average of the 3 runs was assessed. Quality control standards were run with each sample to monitor the consistency of the analysis.

Cellular In Vitro Model of Transport Across the Blood–Brain Barrier

The cellular model in vitro was established using a co-culture of primary blood–brain endothelial cells and newborn rat astrocytes (see Fig. S4) as described elsewhere [36]. The culture was performed in 24-well polycarbonate transwells with a surface area of 0.33 cm2 and pore size of 0.4 μm (Corning Costar, Sigma), and the upper surface of the plate inserts was coated with collagen type IV and fibronectin; 45,000 astrocytes and 45,000 bovine brain endothelial cells were plated sequentially. On day 8 of co-culture, the transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured using an ohmmeter Millicell ERS system (Millipore). The TEER values represent the integrity of the in vitro BBB, and the mean TEER for all the wells was 141 ± 5.7 Ω/cm2 (mean ± S.D.). To validate the maturity of the model, permeability assays were done in parallel with lucifer yellow (LY, 20 μM) on the same day of the experiment as a marker of the integrity of the in vitro barrier. Permeability was calculated using following equation [37–39]:

Where (dQ/dt) is the amount of the compound present in the acceptor compartment as a function of time (nmol/s), A is the area of the insert (cm2), and C0 is the initial concentration of the compound applied to the donor compartment (nmol/ml).

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

Brain Samples

Brain homogenates (100 μl of brain homogenate and 10 μl of the internal standard) were mixed with 250 μl of methanol, and after centrifugation, the supernatants were transferred to a Captiva NDLipids plates (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). The supernatants were filtered and the eluates were evaporated under a steady stream of nitrogen (37 °C) and redissolved with ACN:H2O (1:1) for analysis.

Plasma Samples

Plasma (60 μl) was combined with 18 μl of the internal standard (verapamil 0.125 μM in MeOH:H2O), and an aliquot (25 μl) of each plasma sample (blank, calibration standards, and study samples containing internal standard) was processed on Sirocco Protein Precipitation plates (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with the addition of 375 μl of ACN to each well of the Sirocco plate. The samples were filtered under vacuum (8-10 mmHg) for about 5 min, and the filtrates were evaporated under a steady stream of nitrogen (37 °C) and reconstituted with 150 μl of ACN:MeOH for analysis. Prior to plasma sample preparation, some plasma samples were diluted with PBS as the volume was insufficient to perform the analysis. Samples were analyzed using ACQUITY Ultra Performance LC with a Kinetex C18 2.6 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm column. Details of the pharmacokinetic studies are provided in Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. S4.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with ANOVA test with Tukey post hoc analysis for the in vitro cell assays and the 2-tailed Mann–Whitney U test to assess differences in the clinical score of in vivo studies. p values < 0.05 were considered to indicate a significant difference and the statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS 20.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Screening for Small Chemicals with Neuroprotective Activity in Functional Cell Assays

We set out to identify small chemicals with neuroprotective activity aimed to prevent disability in MS and glaucoma by screening a combinatorial chemical library of peptoids (constructed in positional scanning format) and another 1 of discrete 3-oxopiperazinium and perhydro-3-oxo-1,4-diazepinium compounds using functional in vitro cell assays. The chemical libraries were developed at the Institute for Advanced Chemistry of Catalonia IQAC–CSIC, Barcelona, Spain (Prof Angel Messeguer). The cyclic tetraalkylammonium salts library was comprised of 66 master compounds (44 compounds contained a 6-membered ring, whereas 22 contained a 7-membered ring) [8]. The peptoid (oligomers of N-alkylglycine units) library, constructed under the positional scanning format, was comprised of 5120 compounds [9, 10]. Screening of the peptoid library was performed using controlled combinations of compounds from the same library. For the combinations with positive signals, individual compounds were synthesized and tested. The screening was performed in the rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cell line to evaluate the effects of these compounds on neuronal differentiation [11], as well as in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y and in the rat schwannoma cell line RN22 to assess cell survival in the presence of oxidative stress (H2O2 or CuSO4) [12, 14]. The cells were cultured in the presence of different concentrations of the compounds tested (from 2 to 20 μg/ml). From the screening, we found 3 tetraalkylammonium salts and 3 peptoids with in vitro neuroprotective activity. All 6 compounds were tested for safety and efficacy in an animal model of MS (EAE). The tetraalkylammonium salts were discarded because of toxicity signals. From the peptoids, all were well tolerated and 1 of them (G59) showed the highest efficacy in a dose–effect manner in ameliorating the clinical course of the disease. Therefore, G59 was select as the lead compound. After chemical optimization of G59, we identified the small molecule BN201 as the most effective compound in terms of promoting PC12 differentiation, as well as having the strongest activity in protecting SH-SY5Y and RN22 cells from oxidative stress (Fig. 1A–D and Fig. S1 and Table S1), as well as displaying efficacy in the EAE model (see below). The BN201 compound is a peptoid of 491.5 Da, with high solubility and biodistribution.

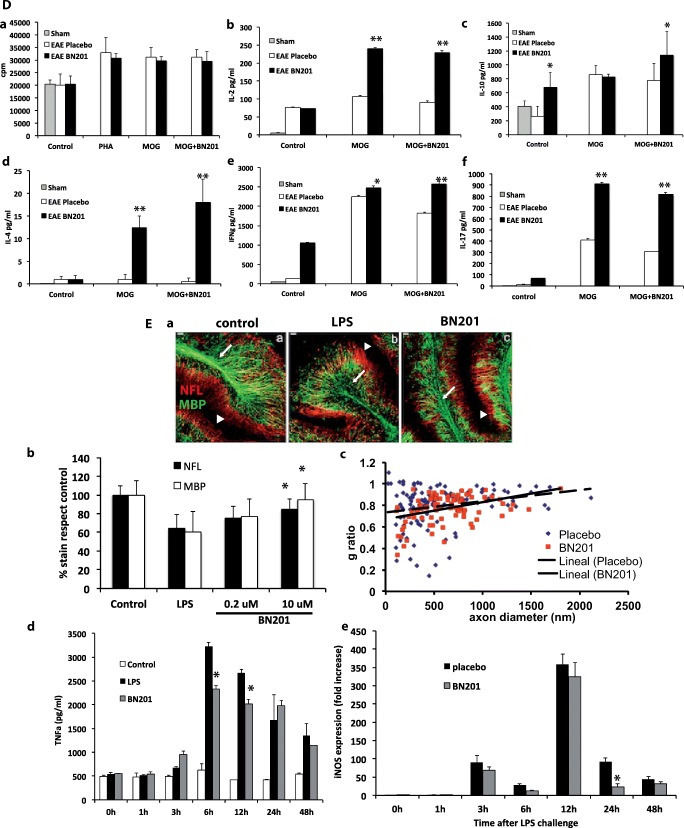

Fig. 1.

Neuroprotective activities of the small chemical BN201. All assays were done in duplicate wells and repeated twice. We used BN201’s dissolving solution as control (saline). Results are shown as the mean + SEM. A BN201 chemical structure (mw 491 Da). B Differentiation of PC12 cells to a neuronal phenotype expressed as the percentage of cells with neurites compared to the positive control NGF (100 ng/ml). C Survival of the myelin cell line RN22 (MTT assay) in the presence of oxidative stress induced with CuSO4 (150 μM). NGF (100 ng/ml) was used as positive control for promoting Schwann cell survival. D Survival of the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y (MTT assay) in the presence of MPTP (100 μM)-induced oxidative stress. BDNF (20 ng/ml) was used as a positive control for promoting neuronal survival. E Survival of SH-SY5Y cells (MTT assay) in the presence of H2O2-induced oxidative stress (100 μM). Sodium pyruvate (10 μM) was used as a positive control for anti-oxidant activity. F Survival of NSC34 cells (MTT assay) under trophic factor deprivation. Positive controls used were the trophic factors G-CSF (2 μg/ml) or BDNF (20 ng/ml). G Differentiation of mice oligodendrocyte precursor cell (OPC) to mature (MBP+) oligodendrocytes (OLs). (a) Graph showing the percentage of mature OLs. (b) Representative micrographs of the MBP staining (arrows) of OPC cultures for placebo, the gamma secretase inhibitor DAPT (1 μM) that promotes OPC differentiation, and BN201 (100 μM). (H) Percentage of myelinated axons in the presence of increasing concentrations of BN201 or positive control (1 μM DAPT in duplicate). Dose selection of positive controls is described in the methods. (a) The graph shows the quantification of the assays. (b) The microphotograph shows a representative picture of the co-cultures of differentiated RGCs and OPCs, showing myelin (MBP+) in red, axons (neurofilaments, NFL) in green, and nuclei (DAPI) in blue. Arrows indicate representative linear MBP+ structures quantified in the analysis. Comparisons between groups were done using ANOVA test, with Tukey post hoc analysis. *p < 0.05 with respect to stressed control

To evaluate the neuroprotection afforded by BN201 in neurodegenerative processes, we tested its ability to prevent the death of human neurons (SH-SY5Y cells) exposed to the mitochondrial toxin MPTP (MPP+, 100 μM) [13] or to oxidative stress (H2O2, 100 μM) [14] in vitro. MPTP-induced stress diminished the viability of these cells (MPP stress 90.5 ± 1.5%), whereas both BN201 (20 ng/ml) and BDNF almost completely prevented neuronal loss (BDNF 104 ± 2.9%; BN201 = 96.6 ± 3.3%: Fig. 1D). The oxidative stress induced by H2O2 significantly reduced the viability of SH-SY5Y cells (40% survival), which was in part impeded in the presence of the antioxidant compound sodium pyruvate (55% survival). BN201 (from 0.03 to 5 nM) protected SH-SY5Y cells against death (47-60% survival) (Fig. 1E). In addition, we tested the efficacy of BN201 in protecting the mouse NSC34 motor-neuron cell line from trophic factor deprivation [15]. BN201 (2 and 20 μg/ml) significantly enhanced the viability of these cells relative to the untreated controls (BN201 = 98.11 ± 6.14%; control = 69.64 ± 10.12%: p = 0.02), and it produced better protection than BDNF or G-CSF used as positive controls (Fig. 1F).

Further, we assessed whether the protective effects observed in RN22 (Schwann) cells might contribute to myelin recovery, a key process in MS and more recently shown in glaucoma [40]. We evaluated the effects of BN201 on the differentiation of OPCs (Olig+ cells) to mature OLs (MBP+) in vitro and on promoting the myelin ensheathing of axons [17]. We cultured primary RGCs from P8 mice and allowed them to differentiate and to produce axons in culture. Then, we added OPCs in the presence of a positive control (the gamma-secretase inhibitor DAPT, 1 μM), placebo, or increasing concentrations of BN201 (from 50 nM to 100 μM). The number of MBP+ cells formed in the presence of BN201 increased in a dose-dependent manner, indicating differentiation of the OPCs to mature OLs (EC50 = 6.3 μM) (Fig. 1G). In addition, the quantification of linear MBP+ structures indicative of the formation of myelin sheaths around axons showed enhanced axon myelination in cultures treated with BN201 or the positive control (EC50 = 16.6 μM) (Fig. 1H). These results indicated that BN201 promoted the differentiation of OPCs to mature OLs and that these mature OLs are capable of myelinating newly formed axons in vitro.

BN201 Activates Neuronal Survival Pathways

In order to explore the mechanism of action of BN201, we performed binding studies on a large panel of tyrosine kinases, GPCRs, and CNS receptors as well as screening interaction with the human neuronal proteome using thermal swift assays. We found that BN201 has physical binding activity with a reduced set of kinases, preferentially with serum–glucocorticoid kinase (percentage of competitive binding with respect to control (by order of efficacy) SGK2: 6.8; SGK1: 25, and SGK3: 33; Kinome assay, DiscoverX). Binding screens for CNS receptors (Express Profile assay from Cerep/Eurofins, Celle L’Evescault), for tyrosine kinase receptors (RTK tkMAX Biosensor Panel, DiscoverX), and GPCRs (gpcrMAX panel from DiscoverX) showed no other additional binding for BN201. Indeed, we conducted additional screening using the cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) in the human neuronal cell line SH-SY5Y, showing 2 clusters of stabilized proteins: ribosomal proteins (annexins, translation initiation factors, RNA/DNA polymerases (TOP1) and helicases (DDX19, DHX)) that are related with heat stress and a cluster including midkine (MDK, also known as neurite growth-promoting factor 2 (NEGF2)), the disulfide-isomerases A3 and A4, and HSP90. Analysis of protein–protein interaction databases pointed to the activation of the midkine–nucleolin–PTGES3 axis, like the SGK pathway, which participates in the trophic factor pathway (PI3K–AKT pathway) and protects neurons against damage (e.g., kainic acid–induced seizures, ischemia, or amyloid beta toxicity) [41].

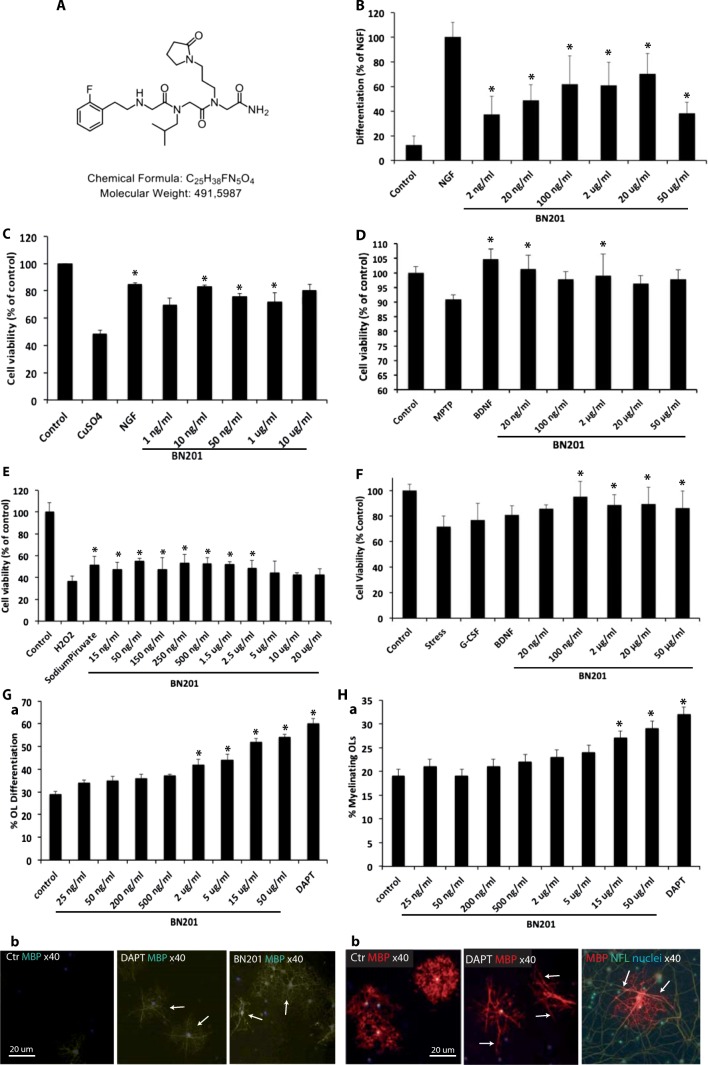

SGKs are expressed strongly in all types of neurons and it is considered to be a stress sensor [42], promoting the expression of antioxidant enzymes and the modulation of ion channels [43], as well as participating in trophic factor pathways (e.g., insulin growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor pathway), promoting neuronal survival. Indeed, MDK also activates the IGF-1 pathway. We hypothesized that BN201, by activating the IGF pathway, would activate downstream proteins such as NDRG1 or Foxo3 [44–46]. Foxo3 is translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, suppressing apoptotic genes and inducing the expression of anti-apoptotic, antioxidant, and prosurvival genes [42]. Based on this background, we analyzed the effects of BN201 in Foxo3 activation, demonstrating that BN201 induced a time-dependent translocation of Foxo3 out of the nucleus in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 2Aa) and a representative image is shown in Fig. 2Ab. Second, we assessed the effects of BN201 in inducing the phosphorylation of NDGR1 in Hela cells. We observed a dose- (Fig. 2Ba) and time-dependent (Fig. 2Bc) phosphorylation of NDRG1 induced by BN201 (ANOVA test: F = 2.606, degree of freedom = 6, p = 0.046, Dunnett’s post hoc test). A representative Western blot is shown in Fig. 2Bb.

Fig. 2.

Activation of the trophic factor pathways by the small chemical BN201. All assays were repeated twice. Time series or dose increasing concentrations assays are shown as the mean; and group comparisons as the mean + SEM. A Translocation of Foxo3 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in SH-SY5Y cells after stimulation with BN201 (100 ng/ml) with respect to nonstimulated animals. (a) Time course of the ratio of cells with Foxo3 in their cytoplasm (per million of cells). (b) Representative image of cultured SH-SY5Y cells before (left) and after (right) stimulation with BN201 (blue: nucleus (DAPI); red: anti-Foxo3 antibody). Cytoplasmic Foxo3 is observed as punctated stain in the cytoplasm (arrows) compared with nuclear Foxo3 (arrowhead), which overlaps with nuclear stain (purple). B (a) Normalized phosphoprotein levels of NDRG1 (with respect to GADPH) by Western blot after 30-min stimulation with increasing concentrations of BN201 (results are shown as the means of 4 repetitions). (b) Representative Western blot for phosphorylated NDRG1 at different times after BN201 (10 μM) stimulation, positive control: dexamethasone (DEX) 1 μM, and other stimulus: insulin (INS) 2 μg/ml or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 10 μM). (c) Quantification of the Western blot: normalized levels of phosphorylated NDRG1 with respect to GADPH in the presence of positive control dexamentasone, stimulus INS or LPS, and BN201 10 μM (30 min, 1 h, and 4 h). C AKT and p706SK phosphorylation assays by flow cytometry in the presence of IGF-1 (100 ng/ml), BN201 (1-10 μg/ml), and 10% FBS or without (wo FBS). D Effects of SGK2 inhibition by RNA interference: (a) representative image of Western blot gels; (b) Western blot quantification. E Effects of SGK2 inhibition by blocking with the SGK1/2 inhibitor GSK650394 (100 nM) in the phosphorylation of NDRG1 after BN201 (10 μM) stimulation: (a) representative image of Western blot gels and b) Western blot quantification. *p < 0.05, ANOVA test

IGF-1 signaling is a prototypic pathway promoting neuronal survival, which is mediated by AKT and mTOR activation (and its downstream kinase p760SK), in addition to SGK or MDK. For this reason, we analyzed whether BN201 activates AKT or mTOR/p760SK. We tested whether SH-SY5Y cells exposed to BN201 (1 or 10 μM) had altered the phosphorylation of AKT and p760SK compared with the phosphorylation induced by IGF-1 as a positive control. BN201 did not induce AKT or p760SK phosphorylation in the absence of fetal bovine serum. By contrast, IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) enhanced the phosphorylation of AKT and, to a lesser extent, the p70S6K kinase (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these results show that BN201 does not induce AKT phosphorylation or mTOR/p760SK activation, and for this reason, the cell survival effects are not attributable to AKT activation.

Finally, we inhibited SGK gene expression using 2 techniques: a) by administration of iRNA and b) by testing the SGK inhibitor GSK650394 in Hela and SH-SY5Y cells. We evaluated NDRG1 phosphorylation under both of these modulators in response to BN201 activation. The SGK2 iRNA reduced the expression of SGK2 in Hela cells up to 60% at 24 h as measured by RT-PCR (Fig. S2). We found that in Hela cells with decreased expression of SGK2, the phosphorylation of NDRG1 induced by either dexamethasone or BN201 (10 μM) was decreased (ANOVA test: F = 4.053, degree of freedom = 5, p = 0.022, Dunnett’s post hoc test) (Fig. 2D). Similarly, in Hela cells pretreated with the SGK inhibitor GSK650394, phosphorylation of NDRG1 in response to either dexamethasone or BN201 (10 μM) was reduced as well (ANOVA test: F = 3.414, degree of freedom = 8, p = 0.019, Dunnett’s post hoc test) (Fig. 2E). Overall, these results support the concept that BN201 mediates its effects, at least in part, by the activation of NDRG1.

BN201 Prevents Axon and Neuron Loss, and It Promotes Remyelination In Vivo in Models of Neuroinflammation

We evaluated the effects of BN201 in protecting neurons and myelin producing cells in vivo using an animal model of MS. We made use of the most common model used for testing therapies, such as the EAE induced in C57BL/6 mice by immunization with MOG35-55. BN201 was administered intraperitoneally because it is able to cross the BBB by active transport (see details in Fig. S3) and has good solubility. In all EAE experiments, therapy always started after disease onset, when animals reached an EAE clinical score > 1.0. Animals were randomized to each treatment after reaching such score and assessed blindly (Fig. 3Aa). Clinical assessment was extended for 30 days in order to cover the early inflammatory and late inflammatory/degenerative phases. Intraperitoneal administration of BN201 to animals after clinical onset (curative trial) ameliorated the clinical course and pathology in a dose-dependent manner, with clinical efficacy starting at 12.5 mg/kg, with the maximum benefit at 50 mg/kg, and with no further added benefit after this dose (up to 100 mg/kg) (Fig. 3Ab). BN201 has high biodistribution after parenteral administration, with intermediate half-life and penetration to the CNS (Table S2 and Fig. S4). We did not observe signs of toxicity at the doses tested. Histological evaluation of the CNS showed that BN201-treated animals displayed less axonal loss and neuron loss in both the spinal cord and in the optic nerve than the animals that received placebo. Moreover, animals displayed significantly smaller areas of demyelination although levels of inflammatory infiltrates did not differ significantly from the placebo group (Fig. 3B).

In terms of defining the efficacy of BN201 in preventing damage in neuroinflammation, we compared its efficacy in the EAE model against other drugs approved for the treatment of MS (GA (intraperitoneal), DMF (oral), or FTY (oral)) and with the neurotrophin small molecule mimetics, xaliproden (intraperitoneal) or gambodic acid (intraperitoneal). All treatments commenced after clinical onset making these therapeutic rather than merely preventive trials, once animals had reached a clinical score > 1.0, and then were randomized to each treatment and assessed in a masked fashion. BN201 produced a stronger amelioration of EAE than either the immunomodulatory drugs GA or DMF or the neurotrophin mimetics xaliproden and gambogic acid and had similar levels of efficacy to FTY (Fig. 3Ac, d).

Microglia are key mediators of the immune damage and protection of the CNS, producing either pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g., iNOS, CD86, or HLA class II for antigen presentation) or tissue protection (arginase or mannose receptor pathways) [47, 48]. For this reason, we analyzed the effects of BN201 in microglia/macrophage pool from mice with EAE at the end of the experiment in the late stages of the disease. Microglia from animals treated with BN201 had decreased gene expression of iNOS and arginase-1 and a significant increase in Mrc1 expression (CD206 or mannose receptor), whereas there were no changes in CD86 gene expression (Fig. 3Cb). At the protein level, there were also a significant reduction in the iNOS protein levels and a significant increase in the Mrc1 protein, whereas CD86 and arginase-1 protein levels were not altered by BN201 (Fig. 3Cc). Overall, treatment of BN201 displayed a tissue protective phenotype.

We set out to assess the effect of BN201 on the autoimmune response to define if BN201 might also modulate the immune system. We analyzed the proliferative response against the immunizing antigen (MOG35-55) in splenocytes of immunized animals by day 12, as well as the cytokine profile in the supernatants of spleen cell cultures obtained from placebo and BN201-treated animals. We did not observe a significant effect of BN201 in the proliferative response in splenocytes from animals that received BN201 either in vivo or in vitro (Fig. 3Da). At the cytokine level, we observed a significant increase in the levels of the IL-2, IFNγ, TNFα, iNOS, and IL-10 by ELISA in splenocytes from BN201-treated animals relative to the placebo group, suggesting a pleiotropic effect in lymphocytes (Fig. 3b–f). Finally, we evaluated whether BN201 modulates Th17-mediated neuroinflammation. T cells were collected by day 12 after immunization with MOG35-55 from C57BL6 mice treated with BN201 (25-50 mg/kg) or placebo and were restimulated in vitro with the MOG35-55 in the presence of IL-23 and in the presence or absence of BN201. The passive transfer of MOG-specific Th17 cells generated from mice treated with BN201 induced EAE with a similar frequency and severity compared with placebo. These results suggest that BN201 did not modulate the encephalitogenic activity of Th17 cells in vitro or in vivo (Fig. S5).

In order to assess the effects of BN201 on focal CNS inflammation, we made use of an in vitro model of neuroinflammation using cerebellar organotypic cultures challenged with LPS [49]. This model involves only microglia activation but not infiltration of hematogenous macrophages, T or B cells. We observed that cultures challenged with LPS have widespread loss of the MBP stain as a marker of demyelination and partial loss of neurofilament (NFL) stain as a marker of axonal density (Fig. 3Ea, b). By contrast, cultures treated with BN201 have a significant preservation of the MBP stain as well as the NFL stain by 24 h after challenge. The analysis of the g-ratio (ratio of the inner to the outer diameter of the myelin sheath) showed that the percentage of unmyelinated axons (g-ratio = 1) was decreased in the BN201-treated cultures (Fig. 3Ec). Considering that such effects were observed 24 h after the challenge, these findings suggest myelin preservation since remyelination would require longer periods of observation. The pretreatment of cultures with BN201 significantly dampened the LPS-induced expression in microglia of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNFα and oxidative stress (iNOS) (Fig. 3Eb, c). These results are concordant with the observed effects in the EAE model, supporting a role of BN201 in shutting down the pro-inflammatory microglia profile, which can be beneficial for preventing CNS damage in patients with MS.

Neuroprotective Effects of BN201 in Models of Chemically Induced Demyelination and Glaucoma

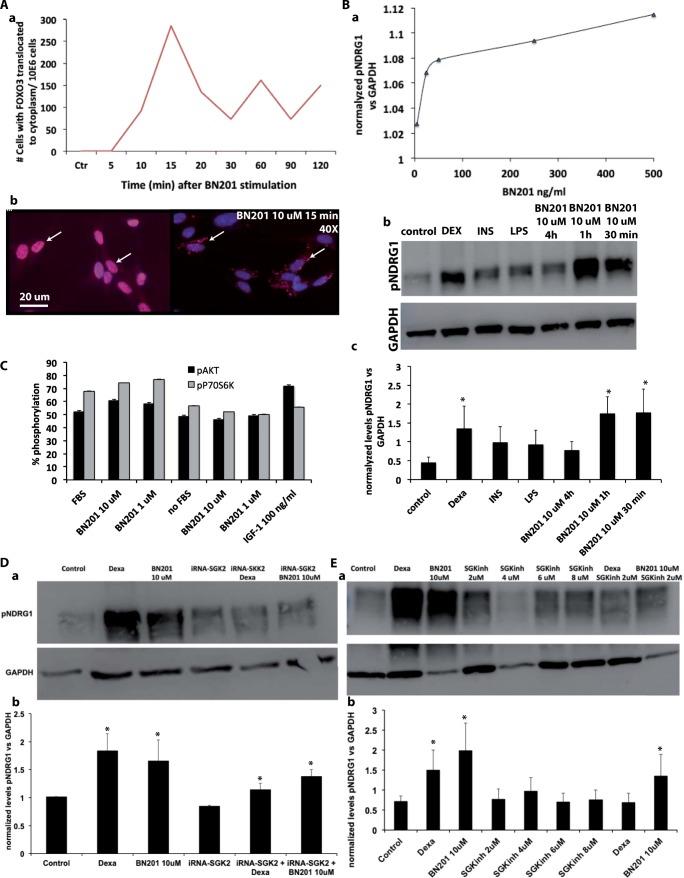

To further distinguish whether the beneficial effects of BN201 might be due to a combination of both immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects, we tested the efficacy of BN201 in protecting neurons, axons, and myelin in models of neurodegeneration and demyelination, which are not mediated by the adaptive immune system like in autoimmune diseases. Because models of demyelinating optic neuritis and glaucoma require surgical procedures, we used rats for these studies for benefiting of their higher sizes. To this aim, we made use of the lysolecithin model, which induces rapid chemical damage to membranes, inducing extensive demyelination, with low levels of axon loss and reactive microglia activation [50]. We evaluated the effects of BN201 (intraperitoneal) (35 and 60 μg/ml/day for 5 days) in Sprague-Dawley rats starting 1 h after injection of lysolecithin into the right optic nerve (preserving the left eye as control). Although myelin damage is evident after seconds in this model, myelin removal occurs later, and as such, demyelination was assessed when it reached a maximum at 5 days after injection. We evaluated the extent of demyelination and axon damage in serial sections of the optic nerve at the level of the injection (indicated with a drop of Evans Blue during injection). We found that BN201 significantly decreases the extent of demyelination and axon loss in the rat optic nerve (Fig. 4A).

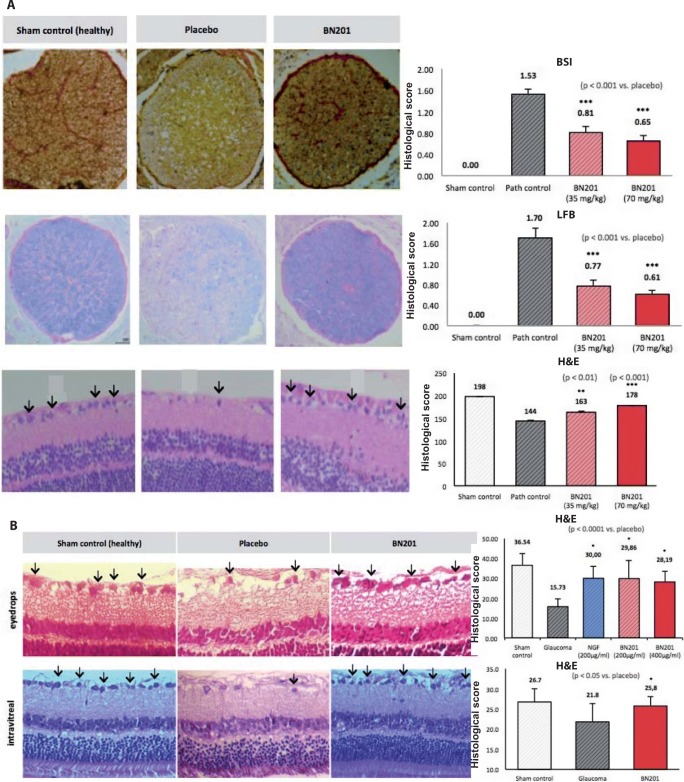

Fig. 4.

In vivo efficacy of BN201 in models of optic nerve demyelination and glaucoma. A Efficacy of BN201 in the lysolecithin-induced demyelination of the optic nerve in Sprague rats. Demyelination was induced by direct injection of lysolecithin in the optic nerve and animals were treated with BN201 (35 or 70 mg/kg) or placebo (saline 5% DMSO) given intraperitoneally started 1 h after damage and performed daily until day 6. Histological analysis was done by day 6 in the injected optic nerve using BSI and LFB stains for quantifying axonal and myelin density and H&E stain for quantifying RGC density. Experiments were performed twice with 10 animals per group. Results are expressed as the mean + SEM. B Efficacy of BN201 in the high intraocular pressure model of glaucoma in Sprague rats. The data from the clinical studies are representative of 2 independent experiments performed with 10 animals per group each. Density of RGCs (arrows) in the retina was assessed in H&E-stained slides. Placebo was saline 5% DMSO. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001

Second, we tested the ability of BN201 to prevent neuronal degeneration in vivo using a model of glaucoma, where inflammation has almost no role and the damage affects the same neurons than in optic neuritis, the RGCs. We employed a glaucoma model induced by high intraocular pressure using hypertonic buffer. In this model, Sprague rats displayed significant loss of RGCs 1 month after the induction of ocular hypertension [51]. In animals treated with BN201, either as eye drops or through intravitreal injection, there were a significant reduction in RGC death compared with those that received the placebo and a similar effect to that seen in positive controls that received nerve growth factor [51] (Fig. 4B). Moreover, we compared the efficacy of BN201 with that of timolol, a common therapy for glaucoma that decreases ocular pressure, demonstrating that both therapies prevented RGC loss compared with placebo. We did not observe signs of toxicity with any of the 2 ways of administration at the doses tested. As BN201 did not decrease ocular pressure, these results suggest that it promotes neuronal survival in the presence of stress and where there is no immune-mediated damage.

Pharmacodynamics of BN201 in the EAE Model

In order to gain insight into the pharmacodynamic effects of BN201 in the CNS, we analyzed serum and CNS levels of BN201 after a single administration in mice suffering EAE compared with placebo-treated animals, observing significant penetrance into the CNS (which are in the range of the concentrations used in the in vitro assays) (Fig. 5A). We also measured the translocation of Foxo3 in neurons as well as the expression of several Foxo3 downstream genes (ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), the antioxidant enzyme Sestrin 3 (SESN3), and iNOS) in the brains of mice with EAE and treated for a short period with BN201 (50 mg/kg, i.p., for 5 days after clinical onset). We analyzed these effects using a short therapeutic protocol aimed to prevent axonal loss during acute relapses of MS.

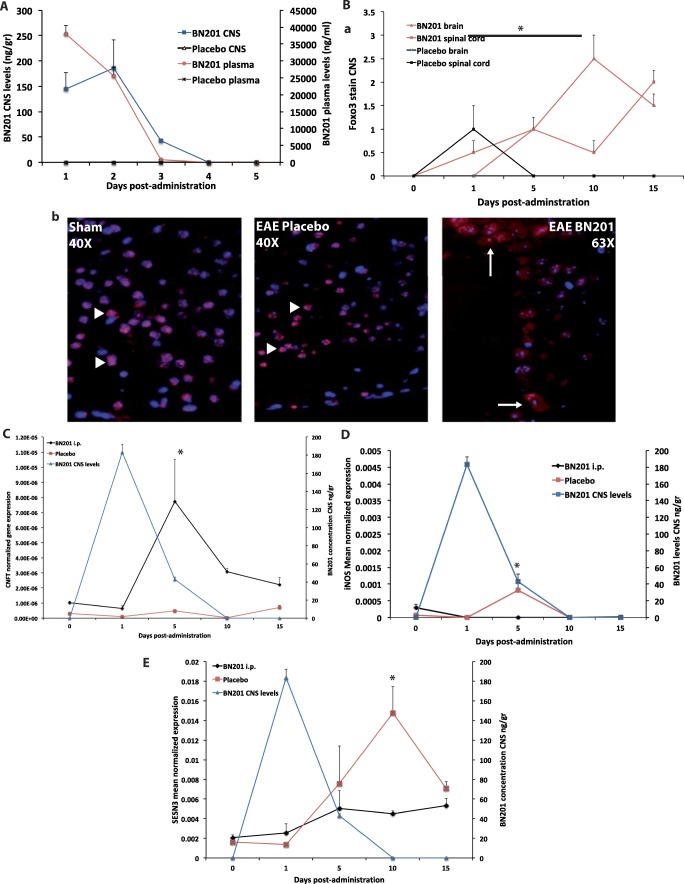

Fig. 5.

Pharmacodynamics of BN201. A Pharmacokinetics of a single administration of BN201 (50 mg/kg/day, i.p.) in plasma and brain in BN201 or placebo-treated animals by HPLC at different time points after injection. B–E The pharmacodynamic properties of BN201 were analyzed in the CNS of EAE animals by assessing the translocation of Foxo3 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in neurons, the expression of the trophic factor CNTF, the antioxidant enzyme SESN3, and the pro-oxidant enzyme iNOS in CNS homogenates. Mice (C57BL6) were immunized with MOG35-55 and treated after clinical onset (clinical score > 1) for 5 days with BN201 50 mg/kg, i.p., or placebo. Results are expressed as the mean of the 5 animals. B Foxo3 translocation to the cytoplasm in cortical and spinal cord neurons: (a) time series of Foxo3 translocation, (b) microphotographs of representative cortical regions showing neuronal nucleus (DAPI, in blue) and Foxo3 (in red) in sham animals, placebo, and BN201-treated mice. Arrowhead shows nuclear Foxo3 (co-localization of Foxo3 stain with DAPI) and arrows indicate cytoplasmic Foxo3 (lack of co-localization of Foxo3 and DAPI). Animals treated with BN201 showed significantly higher levels of Foxo3 translocation than placebo (*p < 0.05 ANOVA test). mRNA levels of CNTF (C), SESN3 (D), and iNOS (E) in the brain homogenates from mice treated with BN201 for 5 days (black line) and the corresponding BN201 CNS levels (in red). *p < 0.05 day 5, 10, or 15 with respect to day 0 of the same treatment group, ANOVA test

We observed significant translocation of Foxo3 in the brain and spinal cord neurons from animals that received BN201 from the day of infusion and extending for 5 to 10 days after the cessation of the treatment, whereas placebo animals showed a transient and modest increase in the translocation of Foxo3, similar to that seen in other models of brain damage (Fig. 5B) [33]. The RNA levels of CNTF peaked by day 5 after treatment started, being reduced slowly once therapy stopped until day 10 (Fig. 5C). RNA levels of SESN3 expression rose steadily from day 1 after therapy onset and remained elevated until day 15 (Fig. 5D). Finally, iNOS gene expression was almost completely suppressed 1 day after therapy started and remained suppressed thereafter (until day 15) (Fig. 5E). Such changes were significantly different than in placebo animals. Overall, we found that BN201 provokes a “hit and run” effect on the activation of Foxo3, which is maintained for several days after the end of the treatment. This is associated with triggering cell-protective effects, as represented by increased expression of CNTF, and the antioxidant response, as shown by the upregulation of the antioxidant enzyme SENS3 and the suppression of pro-oxidative enzyme iNOS.

Discussion

The pursuit of neuroprotective agents is a major goal in the development of therapeutics for inflammatory and degenerative neurological diseases such as MS or glaucoma. From screening 2 combinatorial chemical libraries of peptoids and tetraalkylammonium salts with functional cell assays, we have identified the small compound BN201, which promotes neuroprotection in vitro and in vivo. BN201 is able to cross the BBB by active transport and activate pathways (e.g., IGF-1) associated with the response to stress and neuron survival. Moreover, we obtained proof-of-concept that BN201 provides neuro-axonal protection in vivo by ameliorating the pathological effects in animal models of MS, optic neuritis, and glaucoma.

Our study suggests that the beneficial effects may be mediated by the activation of pathways associated with trophic factor signaling and neuronal survival such as the IGF-1 pathway, mediated by modulation of SGK and midkine [41, 45]. Previous studies have shown neurotrophic effects of SGK1, including the induction of neuronal hypertrophy, protection from neuron death and axonal degeneration, and axonal regeneration [43, 52, 53]. Moreover, MDK also displays prosurvival neuronal effects and protects myelin-forming cells [54, 55]. In summary, although the exact mechanism of action of BN201 remains to be clarified, we have observed that it is able to activate pathways associated with neuronal and axonal survival.

Regarding the effects of such pathways in the immune system, signaling through the mTOR–SGK pathway regulates Th1–Th2–Th17 differentiation [56]. Considering that MS is an autoimmune disease mediated by the Th1 and Th17 immune response, activation of this pathway may downmodulate the pro-inflammatory immune response and prevent CNS damage [57, 58]. Foxo3 also triggers a variety of cellular processes by regulating target genes involved in T- and B-cell survival, proliferation and death, neutrophil survival, and dendritic cell stress resistance and cytokine secretion [59]. Of note, the survival of activated T cells via inhibition of Foxo3a has been associated with clinical relapses in EAE [60]. Our study showed that BN201 has pleiotropic effects in immune cells promoting the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, without enhancing the encephalitogenicity of T cells, suggesting a homeostatic effect on the immune system. For this reason, BN201 would protect the CNS during inflammation without worsening the inflammatory component. However, further characterization of the role of BN201 in the immune system is warranted.

Several limitations apply to our study. Although we have identified several molecular candidates mediating the activity of BN201 such as SGK and midkine, the exact mechanism of action remains to be clarified, including the type of physical interaction on such kinases or other complexes. Indeed, other off-target effects cannot be excluded. Second, BN201 concentrations effective in promoting myelination were higher than the ones promoting neuroprotection in vitro, which might suggest different mechanism of action. In vivo studies do not allow distinguishing if myelin protection was due to neuroprotection against the inflammatory damage or enhanced remyelination. Indeed, the myelination observed in vitro was achieved in young axons and not chronically demyelinated axons, and our assessment is not probing myelin is fully functional. In the model of neuroinflammation in cerebellar cultures, we added BN201 before inducing damage (preventive treatment) in order to perform time series analysis after damage, and for this reason, this experiment does not reproduce the conditions tested in vivo and relevant for the clinical applications. Therefore, the results from such model would require validation. Also, in this study, we have not fully characterized the effects of BN201 in the immune system or in ion channels, and this will require further studies.

Regarding the limitations of the in vivo studies, BN201 induced the expression of several cytokines without biasing the immune response to specific subtypes (e.g., Th1 or Th17), and the size and composition of inflammatory infiltrates within the CNS remained unchanged, suggesting that the benefits observed were due to neuroprotection. However, considering that it is difficult to dissect both effects in the EAE model, the neuroprotective activity of this drug is substantiated in the efficacy in models in which inflammation has no prominent role such as the lysolecithin or the glaucoma model. In our therapeutic trials, we have used as placebo the BN201’s dissolving solution (saline 5% DMSO), but we did not include a biological inactive peptoid. For this reason, we cannot rule out that some of the efficacy may be due to unspecific effects of this type of chemical structures. All the pharmacology and toxicology studies as well as the models of chemically induced demyelination and glaucoma were done in rats, whereas the EAE model was done in mice. Species variability is always an important limitation to be addressed to claim generalization to humans. We have observed a linear relationship of the PK between species (mice, rat, and dog; results not shown), and we have observed lines of evidence of neuroprotection in different models of damage in both rodent species. The pharmacodynamic studies only covered a short period after BN201 administration, and for this reason, we cannot rule out that the effects may be transient. Therefore, our results support that the current observations would be translated to humans, although only human clinical trials will be able to answer this question.

In summary, we have described the discovery and pharmacologic properties of the small chemical BN201 that provides neuroprotective effects in models of inflammatory brain damage relevant for patients with MS and glaucoma. Ongoing clinical studies (NCT03630497) would indicate the safety and efficacy of this therapeutic strategy for preventing brain damage in patients with MS.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(PDF 499 kb)

(DOCX 1849 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof Stephen L Hauser, David Pearce, and Ari Green from University of California, San Francisco; Joaquim Trias and Craig Smith for their scientific advice; and Mr. Mark Sefton for the review of the language of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

VC, BM, BFD, RV, GV, IZ, JMF, NLS, MT, EG, and PV performed the experiments; PV, JMF, EG, JD, LS, and AM designed and supervised the research; JM, GM, and AM synthesized the libraries and the specific small chemicals; JMF and NLS developed the in vitro assays; MT and EG performed the blood–brain barrier assays; VC, BM, BFD, RV, GV, IZ, and PV performed the EAE experiments and evaluated CNS inflammatory infiltration; LS performed the Th17 passive transfer EAE model; VC and RV carried out the experiments with the glaucoma model; RV and PV performed the lysolecithin optic neuropathy model; JD, DL, and KLW performed the in vitro remyelination assays; BM, VC, JMF, EG, AM, and PV analyzed the data; PV prepared the manuscript, which was revised by JMF, EG, and AM; and the statistical analysis was performed by BM, RV, IZ, and PV.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundación Ramon Areces, Madrid, Spain, and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid Spain (RD07/0060 and PI12/01823) to PV and AM and by an unrestricted grant from Bionure SL, Barcelona, Spain.

Data and Materials Availability

All reasonable requests for chemical compounds and assay protocols described in this work will be fulfilled via a material transfer agreement or licensing agreements with the Institut d’Investigacions Biomediques August Pi Sunyer (IDIBAPS) and the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Competing Interest

PV and AM hold a patent covering the composition of matter and uses of BN201. PV is founder and hold stocks in Bionure SL, which has licensed the patent rights to BN201, serves in its scientific advisory board, and had received compensation for such service. MM is an employee of Bionure SL. LS has shares of Bionure SL stock and has received consulting fees.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gooch CL, Pracht E, Borenstein AR. The burden of neurological disease in the United States: a summary report and call to action. Ann Neurol. 2017;81(4):479–484. doi: 10.1002/ana.24897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baeza-Yates R, Sangal PM, Villoslada P. Burden of neurological diseases in the US revealed by web searches. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0178019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tovar YRLB, Penagos-Puig A, Ramirez-Jarquin JO. Endogenous recovery after brain damage: molecular mechanisms that balance neuronal life/death fate. J Neurochem. 2016;136(1):13–27. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabilondo I, Martinez-Lapiscina EH, Martinez-Heras E, et al. Trans-synaptic axonal degeneration in the visual pathway in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(1):98–107. doi: 10.1002/ana.24030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo L, O’Leary DD. Axon retraction and degeneration in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:127–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villoslada P. Neuroprotective therapies for multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. Mult Scl Dem Dis. 2016;1(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almasieh M, Levin LA. Neuroprotection in glaucoma: animal models and clinical trials. Annu Rev Vis Sci. 2017;3:91–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev-vision-102016-061422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masip I, Ferrandiz-Huertas C, Garcia-Martinez C, Ferragut JA, Ferrer-Montiel A, Messeguer A. Synthesis of a library of 3-oxopiperazinium and perhydro-3-oxo-1,4-diazepinium derivatives and identification of bioactive compounds. J Comb Chem. 2004;6(1):135–141. doi: 10.1021/cc030002q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masip I, Perez-Paya E, Messeguer A. Peptoids as source of compounds eliciting antibacterial activity. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2005;8(3):235–239. doi: 10.2174/1386207053764567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montolio M, Messeguer J, Masip I, et al. A semaphorin 3A inhibitor blocks axonal chemorepulsion and enhances axon regeneration. Chem Biol. 2009;16(7):691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burstein DE, Greene LA. Evidence for RNA synthesis-dependent and -independent pathways in stimulation of neurite outgrowth by nerve growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75(12):6059–6063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.12.6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frade JM. Nuclear translocation of the p75 neurotrophin receptor cytoplasmic domain in response to neurotrophin binding. J Neurosci. 2005;25(6):1407–1411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3798-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicotra A, Parvez S. Apoptotic molecules and MPTP-induced cell death. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2002;24(5):599–605. doi: 10.1016/S0892-0362(02)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ill-Raga G, Ramos-Fernandez E, Guix FX, et al. Amyloid-beta peptide fibrils induce nitro-oxidative stress in neuronal cells. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(2):641–652. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka M, Kikuchi H, Ishizu T, et al. Intrathecal upregulation of granulocyte colony stimulating factor and its neuroprotective actions on motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65(8):816–825. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000232025.84238.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lariosa-Willingham KD, Rosler ES, Tung JS, Dugas JC, Collins TL, Leonoudakis D. Development of a central nervous system axonal myelination assay for high throughput screening. BMC Neurosci. 2016;17:16. doi: 10.1186/s12868-016-0250-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuchero JB, Fu MM, Sloan SA, et al. CNS myelin wrapping is driven by actin disassembly. Dev Cell. 2015;34(2):152–167. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu X, Mao H, Liu J, et al. Dynamic change of SGK expression and its role in neuron apoptosis after traumatic brain injury. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 2013;6(7):1282–1293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue K, Sakuma E, Morimoto H, et al. Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinases in microglia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palacios R, Goni J, Martinez-Forero I, et al. A network analysis of the human T-cell activation gene network identifies JAGGED1 as a therapeutic target for autoimmune diseases. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(11):e1222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno B, Hevia H, Santamaria M, et al. Methylthioadenosine reverses brain autoimmune disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(3):323–334. doi: 10.1002/ana.20895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villoslada P, Abel K, Heald N, Goertsches R, Hauser S, Genain C. Frequency, heterogeneity and encephalitogenicity of T cells specific for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in naive outbred primates. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(10):2942–2950. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<2942::AID-IMMU2942>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreno B, Fernandez-Diez B, Di Penta A, Villoslada P. Preclinical studies of methylthioadenosine for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010;16(9):1102–1108. doi: 10.1177/1352458510375968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reick C, Ellrichmann G, Thone J, et al. Neuroprotective dimethyl fumarate synergizes with immunomodulatory interferon beta to provide enhanced axon protection in autoimmune neuroinflammation. Exp Neurol. 2014;257:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kataoka H, Sugahara K, Shimano K, et al. FTY720, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator, ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibition of T cell infiltration. Cell Mol Immunol. 2005;2(6):439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hao K, Liu XQ, Wang GJ, Zhao XP. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and excretion of gambogic acid in rats. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2007;32(2):63–68. doi: 10.1007/BF03190993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bourrie B, Bribes E, Esclangon M, et al. The neuroprotective agent SR 57746A abrogates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and impairs associated blood-brain barrier disruption: implications for multiple sclerosis treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(22):12855–12859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant JL, Ghosn EE, Axtell RC, et al. Reversal of paralysis and reduced inflammation from peripheral administration of beta-amyloid in TH1 and TH17 versions of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(145):145ra105. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.You Y, Klistorner A, Thie J, Graham SL. Latency delay of visual evoked potential is a real measurement of demyelination in a rat model of optic neuritis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(9):6911–6918. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JY, Shen S, Dietz K, et al. HDAC1 nuclear export induced by pathological conditions is essential for the onset of axonal damage. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(2):180–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno B, Vila G, Fernandez-Diez B, et al. Methylthioadenosine promotes remyelination by inducing oligodendrocyte differentiation. Mult Scl Dem Dis. 2017;2(3):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palacios R, Comas D, Elorza J, Villoslada P. Genomic regulation of CTLA4 and multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;203(1):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park SH, Sim YB, Lee JK, Lee JY, Suh HW. Characterization of temporal expressions of FOXO and pFOXO proteins in the hippocampus by kainic acid in mice: involvement of NMDA and non-NMDA receptors. Arch Pharm Res. 2016;39(5):660–667. doi: 10.1007/s12272-016-0733-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez-Forero I, Garcia-Munoz R, Martinez-Pasamar S, et al. IL-10 suppressor activity and ex vivo Tr1 cell function are impaired in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38(2):576–586. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugano K, Hamada H, Machida M, Ushio H. High throughput prediction of oral absorption: improvement of the composition of the lipid solution used in parallel artificial membrane permeation assay. J Biomol Screen. 2001;6(3):189–196. doi: 10.1177/108705710100600309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaillard PJ, de Boer AG. 2B-Trans technology: targeted drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;437:161–175. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-210-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gil ES, Li J, Xiao H, Lowe TL. Quaternary ammonium beta-cyclodextrin nanoparticles for enhancing doxorubicin permeability across the in vitro blood-brain barrier. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10(3):505–16. doi: 10.1021/bm801026k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaillard PJ, Voorwinden LH, Nielsen JL, et al. Establishment and functional characterization of an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier, comprising a co-culture of brain capillary endothelial cells and astrocytes. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;12(3):215–222. doi: 10.1016/S0928-0987(00)00123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madgula VL, Avula B, Reddy VLN, Khan IA, Khan SI. Transport of decursin and decursinol angelate across Caco-2 and MDR-MDCK cell monolayers: in vitro models for intestinal and blood-brain barrier permeability. Planta Med. 2007;73(4):330–335. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-967137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]