Key Points

Question

Is the incidence of nonaffective psychosis higher among refugees compared with the native population and nonrefugee migrants in a host country?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 9 studies, refugees were at a higher relative risk of developing nonaffective psychoses compared with the native population and nonrefugee migrants. In studies with a low risk of bias, the relative risk increased statistically significantly to 1.39 for refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants and to 2.41 for refugees compared with the native population; available evidence was limited to Western host countries only.

Meaning

Refugee experience may represent an independent risk factor in nonaffective psychosis in migrants, which suggests a need for psychiatric prevention strategies and outreach programs for this group.

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates the incidence of and vulnerability to nonaffectiveand affective psychoses among migrant groups in developed countries, using studies identified through PubMed, PsycINFO, and EMBASE.

Abstract

Importance

This systematic review and meta-analysis is, to date, the first and most comprehensive to focus on the incidence of nonaffective psychoses among refugees.

Objective

To assess the relative risk (RR) of incidence of nonaffective psychosis in refugees compared with the RR in the native population and nonrefugee migrants.

Data Sources

PubMed, PsycINFO, and Embase databases were searched for studies from January 1, 1977, to March 8, 2018, with no language restrictions (PROSPERO registration No. CRD42018106740).

Study Selection

Studies conducted in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Canada were selected by multiple independent reviewers. Inclusion criteria were (1) observation of refugee history in participants, (2) assessment of effect size and spread, (3) adjustment for sex, (4) definition of nonaffective psychosis according to standardized operationalized criteria, and (5) comparators were either nonrefugee migrants or the native population. Studies observing ethnic background only, with no explicit definition of refugee status, were excluded.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines were followed for extracting data and assessing data quality and validity as well as risk of bias of included studies. A random-effects model was created to pool the effect sizes of included studies.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome, formulated before data collection, was the pooled RR in refugees compared with the nonrefugee population.

Results

Of the 4358 screened articles, 9 studies (0.2%) involving 540 000 refugees in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Canada were included in the analyses. The RR for nonaffective psychoses in refugees was 1.43 (95% CI, 1.00-2.05; I2 = 96.3%) compared with nonrefugee migrants. Analyses that were restricted to studies with low risk of bias had an RR of 1.39 (95% CI, 1.23-1.58; I2 = 0.0%) for refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants, 2.41 (95% CI, 1.51-3.85; I2 = 96.3%) for refugees compared with the native population, and 1.92 (95% CI, 1.02-3.62; I2 = 97.0%) for nonrefugee migrants compared with the native group. Exclusion of studies that defined refugee status not individually but only by country of origin resulted in an RR of 2.24 (95% CI, 1.12-4.49; I2 = 96.8%) for refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants and an RR of 3.26 (95% CI, 1.87-5.70; I2 = 97.6%) for refugees compared with the native group. In general, the RR of nonaffective psychosis was increased in refugees and nonrefugee migrants compared with the native population.

Conclusions and Relevance

Refugee experience appeared to be an independent risk factor in developing nonaffective psychosis among refugees in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Canada. These findings suggest that applying the conclusions to non-Scandinavian countries should include a consideration of the characteristics of the native society and its specific interaction with the refugee population.

Introduction

Migration is an established risk factor in the development of schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychoses.1 The association of migration with the risk of psychosis has been reported in several meta-analyses.2,3,4,5 Risk of psychosis is increased about 1.8 times, not only in the first generation but also in the second generation of migrants.5

Refugees are a subgroup of migrants who left their home country because of armed conflicts or persecution. They are considered to be at particular risk of developing psychoses because they are more likely to experience a range of physical, psychological, and psychosocial problems associated with adversities such as violence, discrimination, economic stress, and social isolation.1,6 Under international law, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees defined refugees as “persons outside their countries of origin who are in need of international protection because of a serious threat to their life, physical integrity or freedom in their country of origin as a result of persecution, armed conflict, violence or serious public disorder.”6(p1)

The prevalence of mental disorders is high in refugees.7 A systematic review of 7000 refugees who resettled in western countries showed the likelihood of posttraumatic stress disorder to be 10 times higher in refugees compared with the native population in those countries.7 Previous research has focused on the development of posttraumatic stress disorder and affective disorders in refugees7 because refugees are more frequently exposed to traumatic life events than nonrefugees.1 Traumatic life events are also among the most consistent risk factors for a psychotic disorder8; the odds of developing a psychotic disorder or positive psychotic symptoms are increased to 2.8 to 11.5 in persons who experienced traumatic life events.9,10 Proposed theoretical models that associate trauma with psychosis include stress sensitivity, negative schemas, dissociation, information processing biases, and external locus of control, but overall empirical evidence is scarce.8

In addition, the psychosocial adversities of being a refugee in a foreign country are substantial and possibly even greater than for nonrefugee migrants; examples include poverty, separation from family members and significant others, and uncertainty of the outcome of the asylum application process.11,12,13,14 Although psychosocial adversities are detrimental to mental health,11 to what extent the risk of psychosis is increased in refugees remains unclear.1,6

The need for further investigation of mental health problems among refugees is highlighted by the increasing numbers of refugees not only in Europe but also worldwide; the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated the existence of more than 19.9 million refugees worldwide by the end of 2017.15 In addition, the number of persons of concern, including other vulnerable populations such as asylum seekers, internally displaced persons, and stateless individuals, amounted to 71.4 million.15

Single studies and systematic literature reviews1,16 have suggested an elevated risk of psychosis in refugee migrants, but to date, no meta-analysis has been conducted solely on this topic. We aimed to address this shortage of methodologically rigorous evidence by conducting a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the relative risk (RR) of incidence for nonaffective psychosis in refugees. We tested the hypothesis that the RR of incidence of nonaffective psychosis was higher in refugees. This study focused on the incidence of nonaffective psychosis in refugees compared with native populations and nonrefugee migrants according to primarily register-based studies.

Methods

This is a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. The protocol of the overarching project has been published (PROSPERO registration No. CRD42018106740). We followed guidelines by the Cochrane Collaboration for conducting systematic reviews.17 We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines for extracting data as well as assessing data quality and validity and risk of bias.

Search Strategy

In brief, we searched PubMed, PsycINFO, and Embase databases for studies published from January 1, 1977, to March 8, 2018. We assessed the RR of incidence for nonaffective psychoses in refugees and compared the data with those of the native population and nonrefugee migrants. Database search entry terms used are described in eFigure 1 in the Supplement. Additional records were identified through manual searches of the references in the included studies. We included no language restrictions, and we acquired translations from native speakers to test the eligibility of articles written in languages other than English. Study full texts and data were accessible, and contacting the authors of included studies was not necessary. The search was carried out with Endnote, version X8.2 (Clarivate Analytics).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were considered appropriate to test the hypothesis and were included in the analysis if they met the following eligibility criteria. First, specific observation of refugee history was described. Second, the RR (effect size and spread), including rate ratio, risk ratio, or hazard ratio (HR) of incidence of nonaffective psychoses diagnosed according to standard operationalized criteria, was assessed; incidence was defined as first psychiatric contact for a psychotic disorder or first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder within a specified time frame. Third, effect sizes were at least adjusted for sex, or studies needed to display outcomes itemized for sex differences among groups. Fourth, nonaffective psychosis was defined according to standardized operationalized criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD; eg, ICD, Tenth Revision codes F20 through F29, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophreniform disorders but excluding affective psychotic disorders, namely depression, bipolar disorder, and mania with psychotic symptoms). Fifth, the comparator was either nonrefugee migrants or the native population. In addition, the study design had to be either register based or first contact (only if case detection was found to be sufficiently comprehensive with regard to the catchment area).

All definitions of refugee status were included, but definitions with a higher risk of bias (eg, refugee status defined not individually but only by country of origin) were excluded in corresponding sensitivity analyses. Studies observing ethnic background only, with no explicit definition of refugee status, were excluded. Studies were excluded if they focused on subpopulations such as veterans or prisoners.

Study Selection, Data Collection, and Data Extraction

Two of us (S.W. and D.G.) each went through the entire search and screening processes and then compared the results. Consensus in unclear cases was reached via discussion with 2 other members of the team (L.B. and J.H.). Two of us (L.B. and J.H.) also independently performed the testing of eligibility criteria, study selection, and classification and coding of data into a predefined spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel for Mac, version 16.12; Microsoft Corporation), following the recommendations by the Cochrane Collaboration handbook.17

Risk of Bias

Two of us (L.B. and J.H.) individually assessed the risk of bias of studies, using an instrument that was developed and implemented previously.5 In accordance with a validated assessment tool for prevalence studies18 and assessment recommendations by Sanderson et al,19 studies were classified as holding overall low or unknown or high risk of bias on the basis of account selection bias (target population and acquisition), missing cases, information bias (information source, case definition, diagnostic instrument, consistency, and observation period), statistical methods, and conflict of interest. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with other coauthors.

Data Synthesis

We implemented a random-effects model as proposed by DerSimonian and Laird.20 The primary outcome was the pooled RR in refugees compared with the RR in the nonrefugee population accompanied by its 95% CI. Effect sizes of different subgroups (eg, subgroups of nonrefugee migrants) within the same study were pooled with a fixed-effect model. We used HR and rate ratio as an approximation to the RR.21,22 Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using I2 statistics, and effect estimates were interpreted in consideration of present heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome took into account studies with low risk of bias and excluded studies that defined refugee status by only the country of origin irrespective of individual reasons for migration. Additional analyses accounted for potential overlap of study populations. We assessed publication bias using funnel plots and Egger test.

Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp LLC) was used to perform statistical analyses, including the metan1 command for random-effects model. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

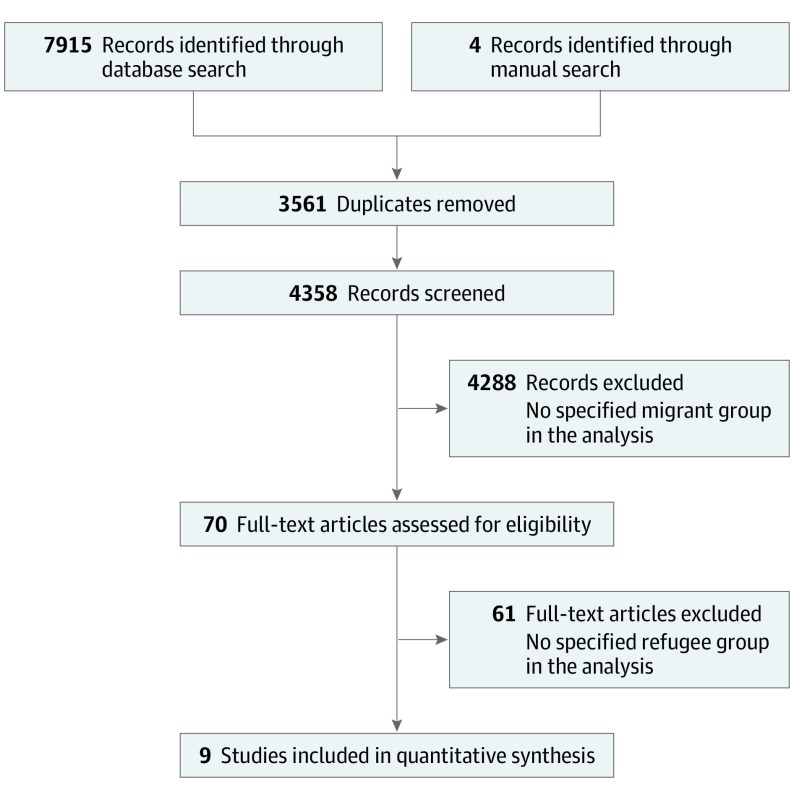

Of the 4358 articles retrieved through the literature search and screened, 9 studies (0.2%) involving 540 000 refugees met the inclusion criteria. These 9 studies, published between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2018, provided sufficient data to be included in this analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart.

The 9 studies presented data on refugee and native groups. Among these studies, 7 (78%) reported separate outcomes for nonrefugee migrants. Eight studies (89%) provided register-based data. One study (11%) was a first-contact or admission study but ensured comprehensive coverage of a catchment area to minimize case leakage. Four studies (44%) presented data on inpatients only. Observations originated from target populations in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Canada. Included studies assessed rate ratios or HRs. One study (11%) provided data for schizophrenia only (ICD, Ninth Revision, and ICD, Tenth Revision F20 code) (Table).

Table. Characteristics of Included Studies .

| Source | Country or Region of Native Population | Origin or Ethnicity of Refugees or Migrantsa | Generation and Age Group of Refugees or Migrants | Diagnosis (Standardized Criteria) | Study Population, Total No. (No. of Refugees) | Cases of Psychosis Among Refugees, No. | Observation Period | Cohort | Relative Risk | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al,32 2015 | Ontario, Canada | NS | First; 14-40 y | Schizophrenia; nonaffective psychosis (ICD-9, ICD-10, and DSM-IV) | 4 284 694 (95 148) | NS | 1999-2008 | Register based; refugee; nonrefugee | Effect measure rate ratio | Low |

| Barghadouch et al,25 2018 | Denmark | 1 | First; migrated <18 y | Schizophrenia; nonaffective psychosis (ICD-10) | 114 577 (15 264) | 95 | 1994-2012 | Register based; refugee | Effect measure rate ratio | Low |

| Hollander et al,24 2016 | Sweden | 2 | First; >14 y | Schizophrenia; nonaffective psychosis (ICD-10) | 1 347 790 (24 123) | 93 | 1998-2011 | Register based; refugee; nonrefugee | Effect measure HR | Low |

| Iversen and Morken,23 2003 | Norway | 3 | First; mean 30.8-41.4 y | Schizophrenia (ICD-9 and ICD-10) | 139 795 (Mean asylum seekers/y: 205) | 5 (Asylum seekers) | 1995-2000 | Inpatient only; first psychiatric contact/admission; refugee; nonrefugee | Effect measure rate ratio | Unknown or high |

| Saraiva Leão et al,26 2005 | Sweden | 6 | Second; 16-34 y | Schizophrenia; nonaffective psychosis (ICD-9 and ICD-10) | 1 914 703 (33 698) | 82 | 1995-1998 | Register based; inpatient only; first psychiatric contact/admission; refugee; nonrefugee | Effect measure HR | Unknown or high |

| Leão et al,27 2006 | Sweden | 7 | First, second; 20-39 y | Schizophrenia; nonaffective psychosis (ICD-9 and ICD-10) | 2 243 546 (First generation: 68 557; second generation: 3267) | NS | 1992-1999 | Register based; inpatient only; first psychiatric contact/admission; refugee; nonrefugee | Effect measure HR | Unknown or high |

| Manhica et al,50 2016 | Sweden | 4 | First; migrated <19 y | Schizophrenia; nonaffective psychosis (ICD-10) | 1 275 743 (13 780) | 270 | 2005-2012 | Register based; refugee; nonrefugee | Effect measure HR | Low |

| Norredam et al,51 2009 | Denmark | 5 | First; migrated >18 y | Schizophrenia; nonaffective psychosis (ICD-10) | 145 695 (29 139) | 371 | 1994-2003 | Register based; refugee | Effect measure rate ratio | Low |

| Sundquist et al,28 2004 | Sweden | 8 | First; 25-64 y | Schizophrenia; nonaffective psychosis (ICD-9 and ICD-10) | 4 437 491 (259 402) | NS | 1997-1999 | Register based; inpatient only; first psychiatric contact/admission; refugee; nonrefugee | Effect measure rate ratio | Unknown or high |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; ICD-9 or ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision or Tenth Revision; NS, not specified.

Includes the following:

1: Asia, Middle East and North Africa, former Yugoslavia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

2: Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe and Russia.

3: Asylum seekers currently residing in a reception center from Russia, former Yugoslavia, rest of Europe, Iran, rest of Asia, Ethiopia, and rest of Africa.

4: East Africa and Latin America (nonrefugee migrant cohort comprised adoptees only).

5: Asia, Eastern Europe (excluding former Yugoslavia), former Yugoslavia, Iraq, Middle East (including North Africa), and sub-Saharan Africa.

6: Refugee status defined by country of origin (“Refugee countries were defined as all countries except Sweden, Finland, and labour immigrant countries, e.g. most African countries, Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, the Soviet Union, and all other non-European countries outside the OECD”26(p247)).

7: Refugee status defined by country of origin (“Refugee countries were defined as all countries except Sweden, Finland, and labor immigrant countries, i.e., African countries, Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Czechoslovakia, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldavia, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, the Soviet Union, Tadzhikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, and all other non-European countries outside the OECD”27(p28-29)).

8: Refugee status defined by country of origin (“Eastern European countries, Bosnia, and all other non-European countries”28(p294)).

Main Analysis and Publication Bias

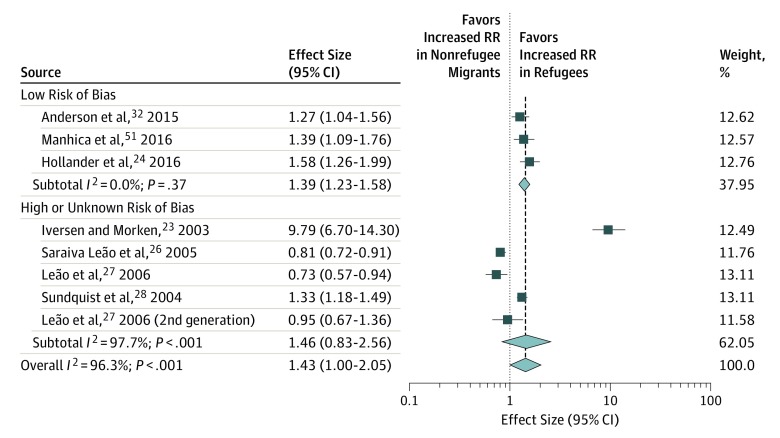

The main analysis included 9 studies. The RR of nonaffective psychosis amounted to 1.43 (95% CI, 1.00-2.05) in refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants. Heterogeneity among studies was high (I2 = 96.3%; Figure 2). Compared with the RR of the native populations, RR was increased by 2.52 (95% CI, 1.78-3.57) in refugees (eFigure 2 in the Supplement) and was increased by 1.85 (95% CI, 1.53-2.24) in nonrefugee migrants. Heterogeneity among studies was invariably high (refugees vs native populations: I2 = 98%; nonrefugee migrants vs native populations: I2 = 94.2%). A funnel plot of the main analysis (refugees vs nonrefugee migrants) and an Egger test did not indicate publication bias (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Relative Risk (RR) of Incidence of Nonaffective Psychosis in Refugees and Nonrefugee Migrants.

The square data markers indicate RR in primary studies, with effect sizes reflecting the study’s statistical weight identified using random-effects meta-analysis. The horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs. The diamond data markers represent the subtotal and overall RR and 95% CI. The vertical dashed line shows the summary effect estimate, and the continuous line represents the line of no effect (RR = 1). Unless otherwise stated, refugees and nonrefugee migrants are first-generation cohorts.

Sensitivity Analyses

When restricting the analyses to studies with low risk of bias only, the RR was 1.39 (95% CI, 1.23-1.58; I2 = 0.0%) for refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants (Figure 2), 2.41 (95% CI, 1.51-3.85; I2 = 96.3%) for refugees compared with the native populations, and 1.92 (95% CI, 1.02-3.62; I2 = 97.0%) for nonrefugee migrants compared with the native group.

Only the study by Iversen and Morken23 provided data not adjusted for age. Adjustment for age was part of the assessment of the methodologic rigor of included studies; consequently, age adjustment was controlled for in the sensitivity analysis of studies with low risk of bias only.

Excluding studies that defined refugee status by country of origin only (so-called refugee countries) yielded an RR of 2.24 (95% CI, 1.12-4.49; I2 = 96.8%) for refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants and an RR of 3.26 (95% CI, 1.87-5.70; I2 = 97.6%) for refugees compared with the native group.

To control for potential partial overlap of study populations, we conducted a sensitivity analysis, taking into account only the 1 Swedish study (Hollander et al 201624) and the 1 Danish study (Barghadouch et al 201825) with the longest follow-up and highest methodologic rigor. The RR amounted to 2.66 (95% CI, 0.99-7.16; I2 = 97.8%) for refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants and 3.36 (95% CI, 1.25-9.01; I2 = 98.0%) for refugees compared with the native populations.

Finnish migrants to Sweden showed a considerably high risk of being hospitalized for psychoses in 2 studies.26,27 In an exploratory analysis, exclusion of this outlier cohort of Finnish migrants to Sweden in the studies by Saraiva Leão et al26 and Leão et al27 increased the RR to 1.69 (95% CI, 1.24-2.32; I2 = 93.6%) for refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants, 2.52 (95% CI, 1.78-3.57; I2 = 98.0%) for refugees compared with the native group, and 1.57 (95% CI, 1.21-2.02; I2 = 94.4%) for nonrefugee migrants compared with the native population.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this systematic review and meta-analysis is the most comprehensive and the first to focus on comparing the RR of nonaffective psychosis in refugees with those of nonrefugee migrants and native populations. The analyses yielded the following main results: The risk of the manifestation of schizophrenia and associated nonaffective psychoses is statistically significantly increased in refugees compared with the native population as well as compared with nonrefugee migrants. The systematic literature search we conducted revealed a paucity of studies that performed direct comparisons and had high methodologic rigor.

Despite the similarity in geographic location and study methods among included studies, their heterogeneity was considerably high. This heterogeneity was mainly from the 3 studies with a high risk of bias (Iversen and Morken,23 Saraiva Leão et al,26 and Leão et al27 [Figure 2]).

The Norwegian study by Iversen and Morken23 reported an exceptionally high risk of nonaffective psychosis in asylum seekers (ie, persons applying for asylum and the formal recognition as refugees). A potential reason for this finding could be the characteristics of asylum seekers in their study compared with refugees in the other studies. All asylum seekers were currently residing in reception centers, which may place added stress during a particularly vulnerable early phase in the new host country and the uncertainties associated with the outcome of the migratory process. In addition, this study was the only one that did not adjust for age.

All of the included studies, except for Saraiva Leão et al26 and Leão et al,27 observed an increased risk of psychosis in refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants. The differing findings in Saraiva Leão et al26 and Leão et al27 seemed to be associated with a higher incidence of psychosis in migrants from Finland. This finding remains to be elucidated, given that it was not observed by the 2 other studies from Sweden (Hollander et al24 and Sundquist et al28). On the contrary, both Hollander et al24 and Sundquist et al28 showed a greater risk of psychosis in refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants, including Finnish nonrefugee migrants. Other migrant or refugee groups in Sweden, such as Latin American refugees or South European labor migrants, also showed more pronounced self-reported ill health compared with Finnish migrants in another study by Sundquist.29 Tinghög et al30 detected higher prevalence of self-reported anxiety and depression and lower subjective well-being in Iraqi and Iranian migrants compared with Finnish migrants in Sweden. In addition, Turkish and Middle Eastern teenaged males showed statistically significantly larger rates of self-reported depression compared with Finnish teenaged males in Sweden in a study by Bursztein Lipsicas et al.31 These findings do not indicate a generally larger risk of mental health problems in Finnish migrants compared with other migrants or refugees in Sweden. The definition of refugee status in the studies by Saraiva Leão et al26 and Leão et al27 possibly resulted in no statistically significant difference between refugees and nonrefugee migrants, given that refugee status was defined by country of origin and not by specific migratory circumstances. The exploratory exclusion from our analyses of the Finnish migrant groups in the 2 studies26,27 decreased heterogeneity among the included studies. All studies invariably showed a greater risk of psychosis in refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants.

Only Anderson et al32 reported no statistically significant association of refugee or migrant status with the risk of psychosis compared with the native group. Their findings, however, may be explained by the examined population. Anderson et al32 included second-generation migrants in the native population, which likely decreased the contrast between migrants as a whole and the native population because second-generation migrants were also known to be at higher risk of psychosis.2,3,5

Heterogeneity was high in most of the present analyses, but sensitivity analyses supported the main findings. Moreover, restricting the analysis to studies with low risk of bias in comparing refugees with nonrefugee migrants statistically significantly reduced heterogeneity (Figure 2). Even in light of the methodologic heterogeneity of the included studies, the findings appear to be sufficiently robust to serve as guiding values. Because only 5 studies were considered to have low risk of bias, more studies of high methodologic rigor are needed to determine precise risk estimates.

The general findings are in line with those of previous research. The RR of psychosis was increased in refugees and nonrefugee migrants in comparison with the native group.2,5 Parrett and Mason1 performed a systematic review of the literature on refugees and psychosis and assessed small and large population-based studies. Their findings confirmed the increased risk of psychosis for first-generation refugees.1

Even the magnitude of observed effect sizes is in line with that in previous research. The most recent meta-analysis on incidence of nonaffective psychosis found the RR in migrants to be 1.77 (95% CI, 1.62-1.93) higher compared with the native group,5 which matches observations in the present analysis (1.85; 95% CI, 1.53-2.24). Consistently, observed RR in refugees compared with native populations was higher (2.52; 95% CI, 1.78-3.57).

Limitations

This meta-analysis confirmed the initial assumption that refugees are particularly vulnerable to developing nonaffective psychoses. The representativeness and validity of these findings, however, are limited by several aspects.

The included studies are, with 1 Canadian exception,32 all from Scandinavian countries. The application of the conclusions from this meta-analysis to other non-Scandinavian countries is therefore limited and should consider the characteristics of the native society and its specific interaction with the refugee population. To date, evidence is available from only a few Western host countries, and the social, economic, and political factors in the association between immigration and mental health may differ substantially among different regions of the world.

Although of limited methodologic comparability, 2 non-Scandinavian studies that did not meet this study’s formal inclusion criteria found the following: Tolmac and Hodes33 reported high representation of refugees among London adolescents aged 13 to 17 years who were psychiatric inpatients with a psychotic disorder diagnosis, and Fuchs34 detected an increased proportion of “expellees” (persons from former eastern territories of Germany who fled after World War II to Bavaria in West Germany) in a group of patients with nonaffective psychosis. These 2 studies suggest that increased risk of psychosis in refugees may not be limited to Scandinavian host countries. More register-based studies from countries with different social, economic, and political characteristics appear to be needed to further assess the generalizability of the findings from the present study.

Register-based studies were included in this meta-analysis because of their methodologic advantages, including large sample sizes, small selection bias, and independently collected data. Nevertheless, certain characteristics of register-based studies may limit interpretation. Not all refugees may be registered as refugees, which may lead to the exclusion of certain refugee subgroups from the analysis, although Scandinavian registries are regarded as reliable sources of research.24 In addition, case ascertainment is based on use of psychiatric services, whereas severity of symptoms or functional level of patients is not reported. The likelihood of seeking out and having access to psychiatric services, particularly in cases of less severe symptoms, may differ among the refugee, migrant, and native groups.35

Psychotic disorders and experiences have been reported to vary between countries of origin.36,37 Furthermore, cultural variance in subjective psychosis concepts may be a challenge for the diagnostic process, even though core symptoms of psychosis appear to overlap between cultures.38,39 The included studies of high methodologic rigor reported that refugees and nonrefugee migrants originated from similar regions, but cultural differences between these 2 groups may still exist. To minimize potential misdiagnoses, we made the evaluation of diagnostic procedures a major component of the methodologic rigor assessment of included studies. We also required disorders to be defined according to well-established and standardized operationalized criteria (ICD-9 or ICD-10 and DSM) and explicit differentiation between affective and nonaffective psychoses as mandatory prerequisites for study inclusion.

Implications

Refugees may be especially vulnerable to developing a psychotic disorder because of a multifactorial combination of pre-, peri-, and postmigratory adversities.11,12,13,14 These hardships include traumatic life events,8,9,10 human rights violations, social exclusion, poverty, restricted access to medical services, and limited possibilities of participating in society.16,32,33

Refugees do not migrate deliberately but are forced to migrate and have possibly faced traumatic experiences8,9,10 before and during migration. For example, a systematic review of the prevalence of torture experience showed rates higher than 30% among asylum seekers in high-income host countries.40 As other research studies have shown, these pre- and perimigratory events may also be associated with increased rates of other mental health problems in refugees, such as affective psychoses and posttraumatic stress disorder.7,28

Postmigratory socioeconomic disadvantage, perceived social exclusion and discrimination, and separation from social networks likely are associated with mental health problems in refugees.11 High incidence rates of 1.7 to 13.2 for schizophrenia have been reported in migrants whose position in society was disadvantaged compared with the native population in 17 population-based studies in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.12 The asylum process for refugees in the host country may have additional negative implications for mental health given that the process can be stressful and has an uncertain outcome.11,41,42 One review suggested an independent adverse effect of detention during the asylum process.43 Problematic interactions with the host country may include general challenges in verbal communication, social exclusion stress, and an impaired integration of new sensory data with prior knowledge, which may lead to aberrant projection errors and the development of positive psychotic symptoms.5 This development may increase the vulnerability to nonaffective and affective psychoses.44

The negative implications of these psychosocial challenges may include increasing not only the risk of psychotic disorders but also the incidence of other nonpsychotic mental illnesses in refugees.7,11 More investigations are needed to assess the full range of mental illnesses in refugees and the mechanisms of their incidence in this cohort.7

These challenges may be of exceptional relevance to refugees compared with nonrefugee migrants because their process of migration was forced and likely less prepared. The need for targeted psychiatric intervention and prevention strategies for refugees is further supported by low utilization rates of psychiatric services, language barriers, and cultural differences.16,35,45,46,47,48,49

Conclusions

The results of this review suggest that refugees are at particular risk of developing nonaffective psychosis compared with the native population and nonrefugee migrants in a host country. Refugee experience may thus represent an independent risk factor for nonaffective psychosis in migrants. We believe that these findings highlight the need for psychiatric prevention strategies and outreach programs for refugees.

eFigure 1. Database Search Entry

eFigure 2. Relative Risk (RR) of Incidence of Non-Affective Psychosis in Refugees Compared to the Native Population

eFigure 3. Funnel Plot of Main Analysis

References

- 1.Parrett NS, Mason OJ. Refugees and psychosis: a review of the literature. Psychosis. 2010;2(2):111-121. doi: 10.1080/17522430903219196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantor-Graae E, Selten J-P. Schizophrenia and migration: a meta-analysis and review. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(1):12-24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourque F, van der Ven E, Malla A. A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first- and second-generation immigrants. Psychol Med. 2011;41(5):897-910. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castillejos MC, Martín-Pérez C, Moreno-Küstner B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the incidence of psychotic disorders: the distribution of rates and the influence of gender, urbanicity, immigration and socio-economic level. Psychol Med. 2018;48(13):1-15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718000235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henssler J, Brandt L, Müller M, et al. Migration and schizophrenia: meta-analysis and explanatory framework. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;(June). doi: 10.1007/s00406-019-01028-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees The refugee concept under international law. Global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/events/conferences/5aa290937/refugee-concept-under-international-law.html. Published March 8, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2019

- 7.Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 2005;365(9467):1309-1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson LE, Alloy LB, Ellman LM. Trauma and the psychosis spectrum: a review of symptom specificity and explanatory mechanisms. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;49:92-105. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Bak M, et al. Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109(1):38-45. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690X.2003.00217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, et al. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(4):661-671. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinzie JD. Immigrants and refugees: the psychiatric perspective. Transcult Psychiatry. 2006;43(4):577-591. doi: 10.1177/1363461506070782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton W, Harrison G. Ethnic disadvantage and schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2000;(407):38-43. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.00007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilliver SC, Sundquist J, Li X, Sundquist K. Recent research on the mental health of immigrants to Sweden: a literature review. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(suppl 1):72-79. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rapp MA, Kluge U, Penka S, et al. When local poverty is more important than your income: mental health in minorities in inner cities. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(2):249-250. doi: 10.1002/wps.20221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Figures at a glance: statistical yearbooks. http://www.unhcr.org/statistics. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- 16.Dapunt J, Kluge U, Heinz A. Risk of psychosis in refugees: a literature review. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(6):e1149-e7. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deeks JJ, Higgins J, Altman DG, Green S Part 1: Cochrane reviews. Part 2: general methods for Cochrane reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. Updated March 2011. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- 18.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934-939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanderson S, Tatt ID, Higgins JP. Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(3):666-676. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177-188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green MS, Symons MJ. A comparison of the logistic risk function and the proportional hazards model in prospective epidemiologic studies. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36(10):715-723. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(83)90165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iversen VC, Morken G. Acute admissions among immigrants and asylum seekers to a psychiatric hospital in Norway. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(9):515-519. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0664-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollander A-C, Dal H, Lewis G, Magnusson C, Kirkbride JB, Dalman C. Refugee migration and risk of schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses: cohort study of 1.3 million people in Sweden. BMJ. 2016;352:i1030-i1038. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barghadouch A, Carlsson J, Norredam M. Psychiatric disorders and predictors hereof among refugee children in early adulthood: a register-based cohort study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(1):3-10. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saraiva Leão T, Sundquist J, Johansson L-M, Johansson S-E, Sundquist K. Incidence of mental disorders in second-generation immigrants in Sweden: a four-year cohort study. Ethn Health. 2005;10(3):243-256. doi: 10.1080/13557850500096878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leão TS, Sundquist J, Frank G, Johansson L-M, Johansson S-E, Sundquist K. Incidence of schizophrenia or other psychoses in first- and second-generation immigrants: a national cohort study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(1):27-33. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000195312.81334.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundquist K, Frank G, Sundquist J. Urbanisation and incidence of psychosis and depression: follow-up study of 4.4 million women and men in Sweden. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:293-298. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.4.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundquist J. Ethnicity, social class and health. A population-based study on the influence of social factors on self-reported illness in 223 Latin American refugees, 333 Finnish and 126 South European labour migrants and 841 Swedish controls. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(6):777-787. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00146-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tinghög P, Al-Saffar S, Carstensen J, Nordenfelt L. The association of immigrant- and non-immigrant-specific factors with mental ill health among immigrants in Sweden. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56(1):74-93. doi: 10.1177/0020764008096163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bursztein Lipsicas C, Mäkinen IH, Wasserman D, et al. Gender distribution of suicide attempts among immigrant groups in European countries–an international perspective. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(2):279-284. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson KK, Cheng J, Susser E, McKenzie KJ, Kurdyak P. Incidence of psychotic disorders among first-generation immigrants and refugees in Ontario. CMAJ. 2015;187(9):E279-E286. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.141420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolmac J, Hodes M. Ethnic variation among adolescent psychiatric in-patients with psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:428-431. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuchs T. Uprooting and late-life psychosis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;244(3):126-130. doi: 10.1007/BF02191885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kluge U, Bogic M, Devillé W, et al. Health services and the treatment of immigrants: data on service use, interpreting services and immigrant staff members in services across Europe. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(S2)(suppl 2):S56-S62. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(12)75709-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18(1):23-33. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00001421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Psychotic experiences in the general population: a cross-national analysis based on 31,261 respondents from 18 countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):697-705. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sartorius N, Jablensky A, Korten A, et al. Early manifestations and first-contact incidence of schizophrenia in different cultures. A preliminary report on the initial evaluation phase of the WHO Collaborative Study on determinants of outcome of severe mental disorders. Psychol Med. 1986;16(4):909-928. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700011910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Napo F, Heinz A, Auckenthaler A. Explanatory models and concepts of West African Malian patients with psychotic symptoms. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(S2)(suppl 2):S44-S49. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(12)75707-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalt A, Hossain M, Kiss L, Zimmerman C. Asylum seekers, violence and health: a systematic review of research in high-income host countries. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):e30-e42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schock K, Rosner R, Knaevelsrud C. Impact of asylum interviews on the mental health of traumatized asylum seekers. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2015;6(1):26286-26289. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.26286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Böttche M, Heeke C, Knaevelsrud C. [Sequential traumatization, trauma-related disorders and psychotherapeutic approaches in war-traumatized adult refugees and asylum seekers in Germany]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016;59(5):621-626. doi: 10.1007/s00103-016-2337-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robjant K, Hassan R, Katona C. Mental health implications of detaining asylum seekers: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(4):306-312. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinz A, Murray GK, Schlagenhauf F, Sterzer P, Grace AA, Waltz JA. Towards a unifying cognitive, neurophysiological, and computational neuroscience account of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2018;46:1388. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koch E, Hartkamp N, Siefen RG, Schouler-Ocak M. [German pilot study of psychiatric inpatients with histories of migration]. Nervenarzt. 2008;79(3):328-339. doi: 10.1007/s00115-007-2393-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schouler-Ocak M, Bretz HJ, Penka S, et al. ; Psychiatry and Migration Working Group of the German Federal Conference of Psychiatric Hospital Directors . Patients of immigrant origin in inpatient psychiatric facilities. A representative national survey by the Psychiatry and Migration Working Group of the German Federal Conference of Psychiatric Hospital Directors. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(suppl 1):21-27. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(08)70058-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Penka S, Faißt H, Vardar A, et al. [The current state of intercultural opening in psychosocial services–the results of an assessment in an inner-city district of Berlin]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2015;65(9-10):353-362. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1549961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tortelli A, Kourio H, Ailam L, Skurnik N. Psychose et migration, une revue de la littérature [in French]. Annales Médico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique. 2009;167(6):459-463. doi: 10.1016/j.amp.2009.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vardar A, Kluge U, Penka S. How to express mental health problems: Turkish immigrants in Berlin compared to native Germans in Berlin and Turks in Istanbul. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(S2)(suppl 2):S50-S55. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(12)75708-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manhica H, Hollander A-C, Almquist YB, Rostila M, Hjern A. Origin and schizophrenia in young refugees and inter-country adoptees from Latin America and East Africa in Sweden: a comparative study. BJPsych Open. 2016;2(1):6-9. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.002048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Norredam M, Garcia-Lopez A, Keiding N, Krasnik A. Risk of mental disorders in refugees and native Danes: a register-based retrospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(12):1023-1029. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0024-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Database Search Entry

eFigure 2. Relative Risk (RR) of Incidence of Non-Affective Psychosis in Refugees Compared to the Native Population

eFigure 3. Funnel Plot of Main Analysis