Abstract

Background

Frailty is common and associated with poorer outcomes in the elderly, but its prognostic value in acute coronary syndromes (ACS) requires clarification. We thus undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the relationship between frailty and poor prognosis in patients with ACS.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase to find literatures which studied the prognostic value of frailty in elderly patients with ACS. Our main endpoints were the all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease (CVD), major bleeding and readmissions. We pooled studies using random-effect generic inverse variance method, and conducted three pre-specified subgroup analyses.

Results

Of 1216 identified studies, 15 studies were included in our analysis. Compared with the normal group, frailty (HR = 2.65; 95%CI: 1.81–3.89, I2 = 60.2%) and pre-frailty (HR = 1.41; 95%CI: 1.19–1.66, I2 = 0%) were characterized by a higher risk of mortality after adjustment. Frailty also was associated with increased risk of any-type CVD, major bleeding and hospital readmissions in elderly patients with ACS. The pooled effect sizes in frail patients were 1.54 (95%CI: 1.32–1.79), 1.51 (95%CI: 1.14–1.99) and 1.51 (95%CI: 1.09–2.10).

Conclusions

Frailty provides quantifiable and significant prognostic value for mortality and adverse events in elderly ACS patients, helping doctors to appraise the comprehensive prognosis risk and to applicate appropriate management strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12877-019-1242-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Frailty, Acute coronary syndromes, Elderly, Prognosis

Background

The accomplishments of cardiovascular prevention have decreased the incidence of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and have delayed the onset age of ACS. The progresses in the treatment of ACS (dual antithrombotic therapy and invasive strategy, e.g. the drug eluting stent) significantly lowers the mortality of ACS and lead to a swift growth in the portion of elderly patients. With the fast population ageing, the mean onset age of ACS patients rises stably in the last decades [1]. Advanced age is one of the forceful prognosticators of mortality and morbidity of ACS. Age as a crucial prognostic marker is presented in the majority of ACS risk scores, including the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score and the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score [2].

Frailty, one of the most important health problems in geriatrics, commonly exists in ACS patients, in part due to mutual risk factors. A frail phenotype representing decreased physiological reserve and increased vulnerability reflects better biological age, therefore, it may cause the heterogeneity in clinical consequences within the elderly patients [3]. Frailty has become a substantial factor in assessment of several special medical situations and been embedded into clinical decision making, such as evaluation of surgical risk and cancer treatment. However, this has not yet become incorporated as part of routine management of ACS.

The well-defined pathways for the management of ACS, largely based on randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence, may not be generalizable to elderly frail patients. Indeed, to date, there is no international guidelines as to how frail ACS patients should be treated. Previous studies have reported frailty was connected with higher mortality or adverse events in ACS patients with some inconsistent information. We therefore undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the significance of frailty on ACS prognosis, including mortality, cardiovascular events, major bleeding and readmission.

Methods

Data sources

The methods of this systematic review and meta-analysis were performed in accordance with the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Statement [4] (Additional file 1: Text S1). A comprehensive literature search was performed up to July 1, 2018. The language was restricted to English. The primary sources were the electronic databases of PubMed and Embase, using various combinations of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and non-MeSH terms: “Frailty” combined with “Myocardial Infarction”, “Acute Coronary Syndrome” and “Heart Attacks”. Additional file 1: Text S2 presents the full search strategy. All results were exported to EndNote for the removal of duplicates. We also screened reference lists of published reviews to identify additional relevant studies.

Study selection and data extraction

The titles/abstracts and full texts were screened by two investigators (Qingyu Dou and Wen Wang) independently. Studies met following criteria were included: (1) performed a well-defined cohort design; (2) used frailty as a major exposure in elderly ACS patients; (3) elderly population with the age of 65 or greater (4) displayed hazard ratio (HR) or relative risk (RR) for outcomes with a 95% confidence interval (CI) or provided sufficient information to calculate these data. Exclusion criteria included: (1) case reports, reviews and conference abstracts; (2) insufficient parameters concerning main outcomes. (3) Using only one item (e.g. low gait speed) as a marker of frailty.

The related information and parameters from all included studies were extracted by two investigators including the first author’s name, the year of publication, the place of study, the design of study, population, sample size, follow-up time, assessment methods of frailty, prevalence for frailty/prefrailty, and HR or RR of main outcomes with 95% CI. The main outcomes included all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events (re-infarction and stroke/TIA), composite outcome of death and cardiovascular events, major bleeding and readmission during follow-ups. When a cohort was represented by two or more studies, all available articles were included to make the most complete analyses. Discrepancies were addressed by discussion with a third author (Hui Wang).

Quality assessment

Two authors independently assessed the quality of studies, and disagreements were re-evaluated by a third author. The Newcastlee-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale [5] was used to evaluate the quality of the literature. The scale assessed the selection of cohorts, comparability of cohorts and the quality of outcomes by 9 parameters. Scores range from 0 to 9. The quality of studies were graded as follows: good (≥ 8 stars); fair (5–7 stars); and poor (< 5 stars).

Statistical analysis

We conducted analyses of adjusted and unadjusted estimates separately. We used relative risk (RR) or hazard risk (HR) as the effect measure for the association of frailty and adverse outcomes. HR or RR was pooled using random-effect generic inverse variance method. Statistical heterogeneity among studies were evaluated with chi-squared and I-squared statistics [6]. We explored sources of heterogeneity using three pre-specified subgroup hypotheses: type of patients (frailty vs pre- frailty); type of ACS (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction vs non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction); follow-up time (during hospital/within 1 month vs ≤ 1 year vs > 1 year). Subgroup analyses were performed if there were at least two studies in each subgroup category. We detected publication bias using visually examining symmetry of funnel plots and Egger’s tests [7]. We performed a sensitivity analysis by omitting retrospective studies. All statistical tests will be performed with the STATA14.0 software. All statistical tests are two sided, P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

Search strategy and research characteristics

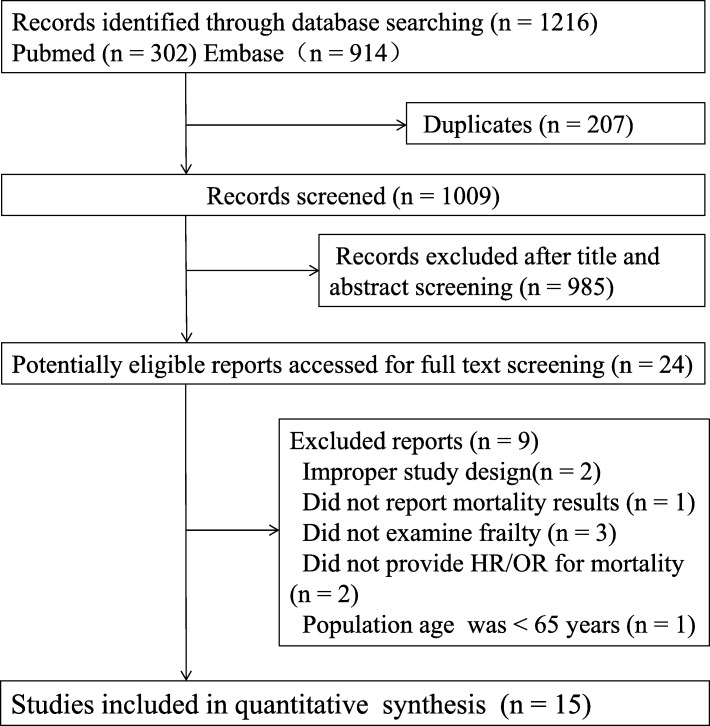

Overall, 1216 publications for possible inclusion were revealed by the initial systematic search of the databases. After the removal of duplicates, the remaining titles/abstracts were examined and irrelevant research were excluded, mainly because they were conference abstracts, reviews and case series. Then 24 left articles were carefully reviewed in full texts. Nine of them were excluded for different reasons. Fifteen studies [8–22] including 8554 patients were finally identified. No additional studies were found after manual inspection of the references. Figure 1 showed the flow chart of literature search strategy and detailed reasons of exclusion.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the selection process

Baseline characteristics of 15 studies [8–22] included are listed in Table 1. The 15 included papers reported data from 13 individual cohort studies. Two papers reported data from one cohort investigating 1 month and 1 year mortality [11, 12]. Another 2 papers studied mortality of average 25 and 56.4 months after ACS from one cohort [17, 18]. There is one retrospective cohort study [19] and the rest are prospective studies [8–18, 20–22]. The studies were conducted in the following countries: Spain, France, Sweden, Canada, Japan, Russia, China and multi-center of the world. All the studies enrolled both men and women with age older than 65 years. The median follow-up time varied from during admission to 56.4 months. Of 15 studies, 1 study enrolled STEMI patients; 4 study enrolled individuals with NSTEMI patients; 6 studies enrolled ACS patients; and 4 studies enrolled type 1 MI.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies on association between frailty and clinical outcomes

| Study | Study type | Location | Type of ACS | Frailty measure | Age | Sample Size (n) | No.of Males | Prevalence (frailty,%) | Prevalence (pre-frailty) | Follow-up (mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ekerstad 2011 | Prospective | Sweden | NSTEMI | CSHA-CFS | ≥ 75 | 307 | 257 | 48.50% | N/A | 1 |

| Ekerstad 2014 | Prospective | Sweden | NSTEMI | CSHA-CFS | ≥ 75 | 307 | 257 | 48.50% | N/A | 12 |

| Graham 2013 | Prospective | Canada | ACS | EFS | ≥ 65 | 183 | 123 | 30.05% | 35.50% | 12 |

| Sanchis 2014 | Prospective | Spain | ACS | Green scores | ≥ 65 | 342 | 196 | 48.00% | N/A | Mean 25 (31–72) |

| Sanchis 2018 | Prospective | Spain | ACS | Green scores | ≥ 65 | 342 | 196 | 48.00% | N/A | Mean 56.4 |

| Kang 2015 | Prospective | China | ACS | CSHA-CFS | ≥ 65 | 352 | 203 | 43.20% | N/A | 6.3 |

| Sujino 2015 | Retrospective | Japan | STEMI | CSHA-CFS | ≥ 85 | 62 | 36 | 35.50% | N/A | in-hospital |

| White 2016 | Prospective | Multicentre | UA/NSTEMI | Fried Frailty score | ≥ 65 | 4996 | 2691 | 4.70% | 23.00% | Mean 17.1 (10.4–24.4) |

| Alonso 2016 a | Prospective | Spain | type 1 MI | SHARE-FI | ≥75 | 190 | 115 | 37.90% | 28.40% | 1 |

| Alonso 2016 b | Prospective | Spain | type 1 MI | SHARE-FI | ≥75 | 202 | 121 | 35.10% | 36.60% | in-hospital |

| Alonso 2017 | Prospective | Spain | type 1 MI | SHARE-FI | ≥75 | 234 | 139 | 40.20% | 28.2% | 6 |

| Alonso 2018 | Prospective | Spain | type 1 MI | SHARE-FI | ≥75 | 285 | 171 | 38.20% | 29.80% | 12 |

| Kirill 2017 | Prospective | Russia | ACS | Computer program of geriatric examination | elderly Senile | 633 | N/A | 35.50% | N/A | 12 |

| Blanco 2017 | Prospective | France | ACS | EFS | ≥ 80 | 236 | N/A | 20.8% | 28.8% | Mean 15.7 |

| Alegre 2018 | Prospective | Spain | NSTEMI | FRAIL scale | ≥ 80 | 532 | 328 | 27.30% | 38.50% | 6 |

CSHA-CFS Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale; EFS Edmonton Frail Scale; STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; ACS acute coronary syndrome; MI myocardial infarction; UA unstable angina; CSHA-CFS Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale; SHARE-FI Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe Frailty Index; N/A not available

The assessment tool of frailty among these studies are as follows: 4 studies [11, 12, 16, 19] used Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale (CSHA-CFS); 4 studies [8, 9, 13, 14] used Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe Frailty Index (SHARE-FI) tool; 2 studies [17, 18] from the same cohort used Green Score; 2 studies [10, 15] used Edmonton Frail Scale (EFS); one [20] used Fried Frailty score; and one [21] used FRAIL scale. One last study [22] determined frailty with the help of computer program “optimization of care in geriatrics, depending on the degree of frailty” on the basis of the specialized geriatric examination. All the 15 studies [8–22] reported the prevalence rate of frailty among participants, ranged from 4.7 to 53.2%. Eight studies [8–10, 13–15, 20, 21] reported the rate of pre-frailty ranged from 23.0 to 38.5%.

Risk of bias assessment

Each study was considered to have adequate methodological quality based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. These 15 included studies [8–22] were of relatively high methodological quality with their scores ranging from 5 to 9 (mean score = 7.4) (Table 2). Eight studies [9, 10, 12–15, 17, 20] were graded as good quality and the rest 7 studies [8, 11, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22] were graded as fair. The representativeness of the exposed cohort, fully adjusted in the analysis and follow-up time were considered to be the most important indicators for methodological quality.

Table 2.

Newcastle-Ottawa Score for the included studies

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ekerstad 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Ekerstad 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Graham 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Sanchis 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Sanchis 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Kang 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Sujino 2015 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| White 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Alonso 2016 a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Alonso 2016 b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Alonso 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Alonso 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Kirill 2017 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Blanco 2017 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Alegre 2018 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

Frailty and adverse outcomes in patients with ACS

Frailty and mortality in ACS

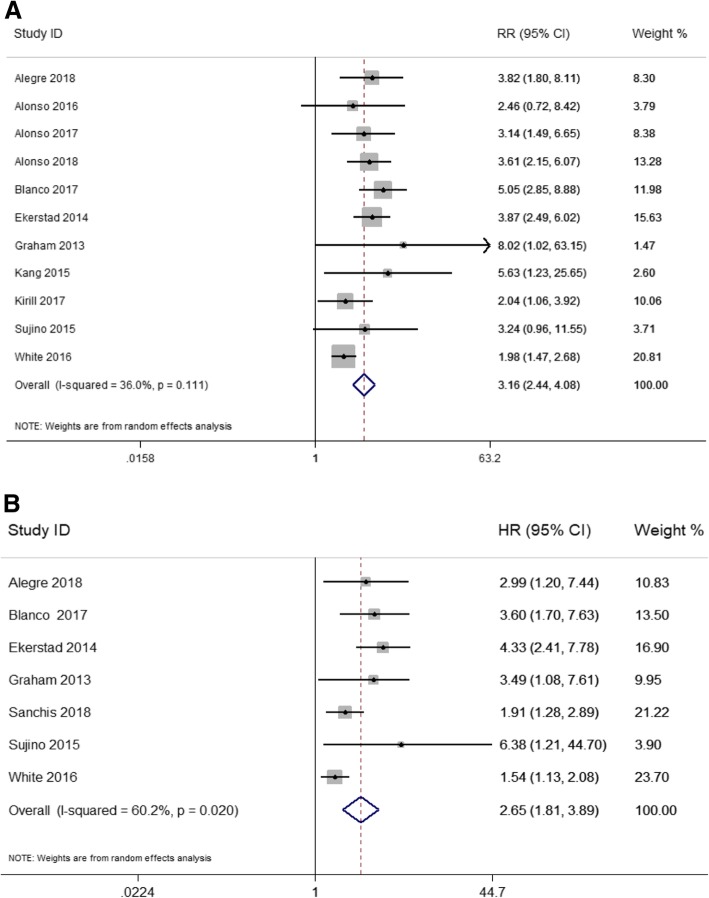

Using crude data, and taking robust patients as the control, frail group presented a significantly higher risk of mortality (RR = 3.16, 95%CI: 2.44–4.08, I2 = 36.0%, P = 0.11). After adjusted for potential confounders, compared to robustness, frailty (HR = 2.65; 95%CI: 1.81–3.89, I2 = 60.2%, P = 0.02) was characterized by a higher risk of mortality. The results were shown in Fig. 2a and Fig. 2b.

Fig. 2.

Frailty and mortality in elderly patients with ACS: a Unadjusted all-cause mortality during the following-ups; b Adjusted all-cause mortality during the following-ups

Frailty and the cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in ACS

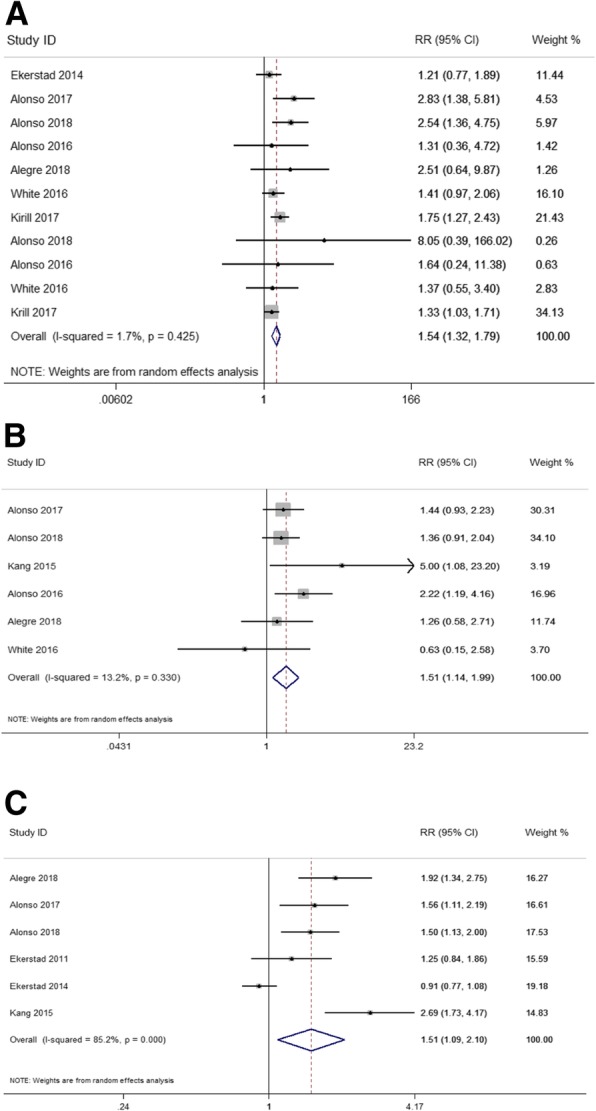

Crude data from 7 studies [8, 9, 12, 14, 20–22] were used to examine the influence of frailty on any-type cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk (re-infarction and stroke/TIA) in ACS patients. The pooled RR demonstrated that ACS with frailty resulted in higher risk of any-type CVD risk during the follow-up (RR: 1.54; 95%CI: 1.32–1.79, I2 = 1.7%, P = 0.425) (Fig. 3a). When analyzing specific CVDs, compared to strong patients, frailty increased the risk of re-infarction of 68% (RR = 1.68, 95%CI: 1.35–2.09, P = 0.31, I2 = 15.5%) and tended to a 1.6-fold raised risk of stroke/TIA (RR = 1.60, 95%CI: 0.72–3.53, P = 0.547, I2 = 0%) (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Frailty and any-type cardiovascular disease (CVD), major bleeding and readmission risk in elderly patients with ACS: a Unadjusted any-type CVD risk during the following-ups; (b) Unadjusted major bleeding risk during the following-ups; c Unadjusted readmission risk during the following-ups

Table 3.

Unadjusted cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in ACS during following-ups

| Outcomes | No. of Studies | Events/Total | RR (95% CI) | P value | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frailty | Control | |||||

| Any-type CVD | ||||||

| Reinfarction | 7 | 170/1031 | 451/4794 | 1.68 (1.35, 2.09) | 0.31 | 15.5% |

| Stroke/TIA | 3 | 9/481 | 61/3906 | 1.60 (0.72, 3.53) | 0.547 | 0% |

| Combined mortality with any type CVD | ||||||

| Combined mortality or reinfarction | 2 | 65/203 | 30/316 | 3.39 (2.28, 5.04) | 0.846 | 0% |

| Combined mortality, reinfarction or stroke/TIA | 2 | 43/180 | 16/307 | 4.39 (2.56, 7.51) | 0.408 | 0% |

CVD cardiovascular disease; TIA transient ischemic attack

When CVD was combined with all-cause mortality, 2 studies [9, 14] reported the composite outcome of death and re-infarction, and 2 studies [9, 13] reported the composite outcome of death and re-infarction or stroke/TIA. The corresponding unadjusted pooled RRs were 3.39 (95%CI: 2.28–5.04, P = 0.846, I2 = 0%) and 4.39 (95%CI: 2.56–7.51, P = 0.408, I2 = 0%) (Table 3). Due to limited information of included studies, adjusted estimates of other outcomes were not performed.

Frailty and major bleeding in ACS

The major bleeding in ACS is defined as patients who had in-hospital intracranial hemorrhage, retroperitoneal bleed, hematocrit drop ≥12%, or need of red blood cells transfusion. Crude data from 6 studies [8, 9, 14, 16, 20, 21] were enrolled in the meta-analysis. We noted that frailty in ACS was associated with the significantly increased risk of major bleeding (RR = 1.51; 95%CI: 1.14–1.99; I2 = 13.2%, P = 0.33). (Fig. 3b).

Frailty and readmission in ACS

Six studies [9, 11, 12, 14, 16, 21] were included in the meta-analysis for the association of frailty in ACS with the risk of readmission. The incidence of readmission was significantly increased by 151% (RR = 1.51; 95%CI: 1.09–2.10, I2 = 85.2%, P = 0) in frail patients (Fig. 3c).

Subgroup analyses and publication bias

Sufficient data were available to conduct subgroup analysis only for mortality. Compared with strong patients, pre-frailty significantly increased unadjusted risk of mortality at follow-up (RR = 1.86, 95%CI: 1.28–2.71, I2 = 40.1%). Similarly, pre-frailty displayed a significantly increased the risk of mortality after adjustment (HR =1.41; 95%CI: 1.19–1.66, I2 = 0%). The incidence of the mortality between frailty and pre-frailty revealed statistical significance before or after adjustment (test for interaction: P = 0.022 and P = 0.003 respectively). This finding illustrated the group of frailty showed higher mortality than pre-frailty group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analyses of all-cause mortality according to the degree of frailty, follow-up time and type of ACS

| Subgroup | No. of Studies | Unadjusted RR (95%CI) |

I2 | P value of interaction | No. of Studies | Adjusted RR (95%CI) |

I2 | P value of interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The degree of frailty | ||||||||

| Frailty | 11 | 3.16 (2.44, 4.08) | 36.0% | 0.022 | 7 | 2.65 (1.81, 3.89) | 60.2% | 0.003 |

| Pre-frailty | 4 | 1.86 (1.28, 2.71) | 40.1% | 4 | 1.41 (1.19, 1.66) | 0% | ||

| Follow-up time | ||||||||

| During admission/within 1 m | 3 | 3.63 (1.91, 6.90) | 0% | 0.96 | 2 | 3.97 (1.65, 9.57) | 0% | |

| ≤ 1 year | 7 | 3.44 (2.67, 4.44) | 0% | 3 | 3.80 (2.45, 5.90) | 0% | 0.18 | |

| > 1 year | 2 | 3.06 (1.23, 7.65) | 58.8% | 3 | 2.13 (1.32, 3.44) | 73.3% | ||

| Type of ACS | ||||||||

| STEMI | 2 | 2.13 (1.11, 4.09) | 0% | 0.45 | 2 | 6.51 (2.01, 21.10) | 0% | 0.17 |

| NSTEMI | 4 | 2.88 (1.86, 4.47) | 58.8% | 4 | 2.63 (1.51, 4.60) | 73.5% | ||

STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; ACS acute coronary syndrome

Second, subgroup analyses were conducted according to follow-up time, which can be categorized by three periods, including short-term (during admission or within 30 days), mid-term (follow-up time ≤ 1 year) and long term (follow-up time > 1 year). Overall, frail patients compared with the normal group experienced a similar unadjusted significantly increased risk for short (RR = 3.63; 95%CI: 1.91–6.90, I2 = 0.0%), mid (RR = 3.44; 95%CI: 2.67–4.44, I2 = 0.0%) and long-term (RR = 3.06; 95%CI: 1.23–7.65, I2 = 58.8%) mortality. After adjustment, frail patients still showed significantly increased risk for short (HR = 3.97; 95%CI: 1.65–9.57, I2 = 0.0%), mid (HR = 3.8; 95%CI: 2.45–5.90, I2 = 0.0%) and long-term (HR = 2.13; 95%CI: 1.32–3.44, I2 = 73.3%) mortality. The risks of mortality between subgroups did not show statistical significance (test for interaction: P > 0.05). The risk of mortality at different time after ACS were all increased by frailty (Table 4).

We also did the subgroup analyses to learn the connection between the different types of ACS and the mortality. STEMI and NSTEMI frail patients displayed significantly increased risk for mortality without adjustment (RR: 2.13, 95%CI: 1.11–4.09, I2 = 0.0% and RR: 2.88, 95%CI: 1.86–4.47, I2 = 58.8% respectively). When using the adjusted data, frailty was associated with significantly increased risk of mortality in STEMI (HR = 6.51, 95%CI: 2.01–21.10, I2 = 0%) and NSTEMI (HR = 2.63, 95%CI: 1.51–4.60, I2 = 73.5%) patients. No statistically significance was detected between subgroups (test for interaction: P > 0.05). The results exhibited that frailty was a significant prognostic factor in either STEMI or NSTEMI, regardless of intra-hospital percutaneous coronary intervention (Table 4).

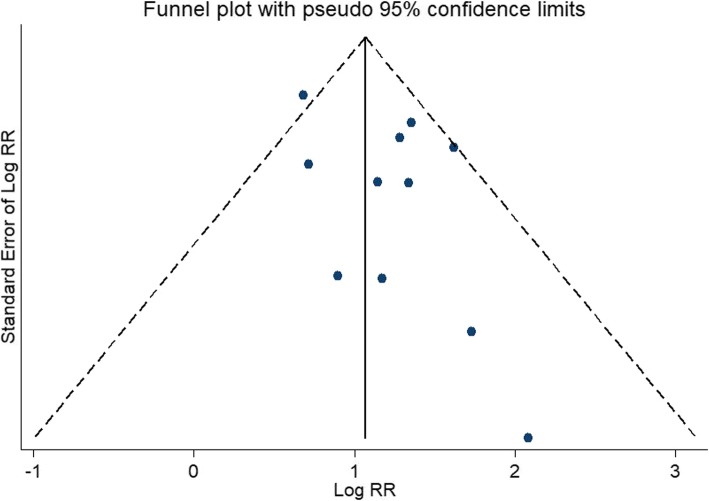

No evidence of publication bias was found for the outcomes of unadjusted relative risk of all-cause mortality (Egger’s test P = 0.123, Fig. 4). Due to limited numbers of included studies, we did not investigate publication bias for other outcomes.

Fig. 4.

Funnel plots of studies included in the meta-analysis for unadjusted all-cause mortality

Sensitivity analysis by omitting Sujino’s retrospective study did not show important changes in the pooled unadjusted (RR =3.17, 95% CI 2.42–4.17, I2 = 42.3%) and adjusted estimates (HR =2.65, 95% CI 1.77–3.98, I2 = 68.4%).

Discussion

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, case series, conference abstracts or reviews, and studies used different exposure or outcome assessment were excluded. All the 15 included studies were of relatively high methodological quality. In the sensitivity analysis, the results were stable after the retrospective study by Sujino was removed. Our results demonstrated in elderly ACS patients, frailty significantly increased the all-cause mortality risk by 2.65-fold, any-type CVD risk by 1.54-fold, major bleeding risk by 1.51-fold and hospital readmissions risk by 1.51-fold.

A previous systematic review reported that the overall prevalence of frailty, in community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older, is on average 10.7%. Moreover, prevalence of frailty increases with age, reaching 15.7% in individuals aged 80 to 84 and 26.1% in those aged 85 or more [23]. The proportion of frailty and pre-frailty in our meta-analysis were significantly higher than community population. Both ACS and frail patients had higher rates of common existed CVD risk factors, like hypertension, type 2 diabetes and lack of exercise. However, regardless of these possible mixed CVD risk factors, frailty itself brings about increased risk of CVD [24]. The pathophysiologic mechanism of frailty, including elevated inflammatory state (interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein [25]), higher markers of thrombosis (D-dimer [25]) and endocrine unbalances (lower insulin-like growth factors − 1 [26]) could act a part in the onset and outcome of ACS. Furthermore, frailty has accelerated biological aging modifications(e.g. higher oxidative stress levels [27], impaired autophagy [28] and shorter telomere length [29] that further give impetus to the development and poor prognosis of ACS.

Frailty could impose obvious influence on the management of elderly ACS patients, especially on revascularization. Since the risk of operational complication rises in frail patients, a less invasive strategy may be preferred. Observational study shows primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was performed less frequently in patients with frailty compared with their non-frail counterparts [30]. For STEMI patients, timely reperfusion in all patients with ischemia symptoms and persistent ST-segment elevation within 12 h, is the cornerstone of treatment. Studies have demonstrated performing PCI reduced in-hospital mortality, even in patients ≥80 years with frailty [19, 22]. Since our meta-analysis found frailty increased the risk of major bleeding, primary PCI is safer than fibrinolytic therapy especially in high risk elderly STEMI patients with frailty. However, frailty greatly increases all-cause mortality by 6.51-fold in STEMI patients in our study, which may reduce the ability to benefit from interventions. In these extremely frail STEMI patients with a high mortality despite intervention, the death risk should be fully informed and requires a shared decision by doctors and families. The decision not to accept interventional therapy is understandable and reasonable.

The role of an invasive strategy in frail NSTEMI patients is still worth exploring. An early invasive strategy was found to have more benefit in the elderly than younger patients, unless there were extensive and complicated comorbidities [31, 32]. Nowadays, there are studies aimed to judge whether the prognostic impact of PCI in NSTEMI differs across frailty status. The LONGEVO-SCA registry included unselected NSTEMI patients aged ≥80 years. The incidence of cardiac events was more common in patients managed conservatively after adjusting for confounding factors. However, this association was not significant in patients with established frailty criteria [33]. In recent Nuñez’s study [34], a prospective observational study of 270 elderly patients hospitalized for NSTEMI, at a median follow-up of 4.4 years, in patients with Fried ≥3, PCI was associated with a significant reduction of risk of all-cause and cardiovascular-rehospitalizations without reducing all-cause mortality. In 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of NSTEMI, revascularization in elderly patients should be took into consideration after cautious weighing up benefits and risks, including comorbidities, frail state, predicted life expectancy, quality of life, and patient preferences [35].

With regard to medical treatment, as bleeding risk increases with age, comorbidities, polypharmacy and declined renal function, elderly patients are at particular risk of bleeding. In addition to routine evaluation of bleeding risk (HAS-BLED bleeding score), based on our study, we also recommend that the frailty assessment be considered to tailor the individualized antithrombotic treatment for elderly patients. It is essential to reduce bleeding risk according to the degree of frailty; these include employing proper dosage of antithrombotic drugs, avoidance of a glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa-inhibitor; adding a proton pump inhibitor; avoiding the use of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs and using radial access whenever possible [36].

Our study found frailty increases both the risk of major bleeding and the risk of cardiovascular events. It is impossible to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events by increasing the intensity of antiplatelet therapy. Frail patients are also less likely to take angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers or β-blockers, since they are more likely to have adverse drug reactions from medical therapy. The frailty as a therapeutic goal intervened by non-pharmacological means is the future hotspot of research. The earlier stage of frailty is reversible and could be remedied. The non-pharmacological interventions (e.g. cardiac rehabilitation, physical exercise, and removing unnecessary medications may postpone and reduce the risk of CVD [37, 38]. A recent study showed patients with diabetes mellitus who have undergone PCI, cardiac rehabilitation participation was associated with significantly reduced all-cause mortality and composite end point of mortality, myocardial infarction, or revascularization [39]. Meanwhile, nutritional supplement with 25–30 g of high-quality protein per meal have slowed or prevented sarcopenia, a manifestation of pre-frailty [40]. In particular, physical activity interventions might play a pivotal role in the prevention of both CVD and frailty. More studies are required to confirm its function and establish standard exercise prescriptions.

Limitation

There are following limitations in our meta-analysis. First, even though we performed subgroup analysis according to type of ACS and follow-up time, there were not sufficient data to detect the statistical difference between subgroups. Second, the included criterion of our review was based on the age of 65 years or more. However, two studies just recruited participants older than 80 years and another study only included STEMI patients older than 85 years, which may result in the heterogeneity of our studies. Last, none of included studies in our meta-analysis reported results concerning quality of life. Future studies should use more patient-centered consequences such as activity of daily living (ADL) as primary outcome.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that in elderly ACS patients, frailty assessment should be integrated into the current existing management to better appraise the comprehensive prognosis risk. The identification of frailty help doctors to applicate appropriate management strategies including invasive therapy and antithrombotic medication, and help patients make properly informed choices. Further, the value of frailty as a therapeutic target should be given full attention. Currently, there is little evidence that frailty management could improve outcomes of elderly ACS patients. It is necessary to conduct more studies related the effect of the frailty intervention on elderly ACS prognosis in the future.

Additional file

Text S1: MOOSE Checklist. Text S2: Search Strategy. (DOC 63 kb)

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACS

acute coronary syndromes

- ADL

activity of daily living

- CI

confidence interval

- CSHA-CFS

Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- EFS

Edmonton Frail Scale

- GP

glycoprotein

- GRACE

Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events

- HR

hazard ratio

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MOOSE

Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- N/A

not available

- NSTEMI

non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- RR

relative risk

- SHARE-FI

Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe Frailty Index

- STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

- TIMI

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

- UA

unstable angina

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: QYD, Acquisition of data: QYD and WW, Analysis and interpretation of data: QYD, WW, HW and YM, Drafting of the manuscript: QYD, SH, XFL, YL and XJZ, Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JHW and BRD, All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by following grants:

Design of the study: Key Research and Development Project of Science and Technology Commission Foundation of Sichuan Province (2018FZ0036).

Database query and collection of data: 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZY2017201); National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFC0840100).

Analysis and interpretation of data: Building World-class Universities (disciplines) and Guiding Special Funds (2040204401004).

Drafting and revision of the manuscript: Sichuan Science and Technology Infrastructure Platform Construction Special Funds (2018TJPT0015); Science and Technology Project of Sichuan Province (0040205302202)

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qingyu Dou and Wen Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jinhui Wu, Email: wujinhui@scu.edu.cn.

Birong Dong, Email: birongdong@163.com.

References

- 1.Montilla Padilla I, Martin-Asenjo R, Bueno H. Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in geriatric patients. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26(2):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai X, Busby-Whitehead J, Alexander KP. Acute coronary syndrome in the older adults. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2016;13(2):101–108. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Jama. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa scale: comparing reviewers' to authors' assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso Salinas GL, Sanmartin Fernandez M, Pascual Izco M, Marco Del Castillo A, Rincon Diaz LM, Lozano Granero C, Valverde Gomez M, Pastor Pueyo P, Del Val MD, Pardo Sanz A, et al. Frailty predicts major bleeding within 30days in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:590–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso Salinas GL, Sanmartin M, Pascual Izco M, Rincon LM, Martin-Acuna A, Pastor Pueyo P, Del Val MD, Marco Del Castillo A, Recio-Mayoral A, Martin-Asenjo R, et al. The role of frailty in acute coronary syndromes in the elderly. Gerontology. 2018;64(5):422–429. doi: 10.1159/000488390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanco S, Ferrieres J, Bongard V, Toulza O, Sebai F, Billet S, Biendel C, Lairez O, Lhermusier T, Boudou N, et al. Prognosis impact of frailty assessed by the Edmonton frail scale in the setting of acute coronary syndrome in the elderly. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(7):933–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekerstad N, Swahn E, Janzon M, Alfredsson J, Lofmark R, Lindenberger M, Carlsson P. Frailty is independently associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124(22):2397–2404. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.025452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekerstad N, Swahn E, Janzon M, Alfredsson J, Lofmark R, Lindenberger M, Andersson D, Carlsson P. Frailty is independently associated with 1-year mortality for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(10):1216–1224. doi: 10.1177/2047487313490257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonso Salinas GL, Sanmartin Fernandez M, Pascual Izco M, Martin Asenjo R, Recio-Mayoral A, Salvador Ramos L, Marzal Martin D, Camino Lopez A, Jimenez Mena M, Zamorano Gomez JL. Frailty is a short-term prognostic marker in acute coronary syndrome of elderly patients. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5(5):434–440. doi: 10.1177/2048872616644909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso Salinas GL, Sanmartin M, Pascual Izco M, Rincon LM, Pastor Pueyo P, Marco Del Castillo A, Garcia Guerrero A, Caravaca Perez P, Recio-Mayoral A, Camino A, et al. Frailty is an independent prognostic marker in elderly patients with myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(10):925–931. doi: 10.1002/clc.22749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham MM, Galbraith PD, O'Neill D, Rolfson DB, Dando C, Norris CM. Frailty and outcome in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(12):1610–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang L, Zhang SY, Zhu WL, Pang HY, Zhang L, Zhu ML, Liu XH, Liu YT. Is frailty associated with short-term outcomes for elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome? J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12(6):662–667. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchis J, Bonanad C, Ruiz V, Fernandez J, Garcia-Blas S, Mainar L, Ventura S, Rodriguez-Borja E, Chorro FJ, Hermenegildo C, et al. Frailty and other geriatric conditions for risk stratification of older patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2014;168(5):784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchis Juan, Ruiz Vicente, Ariza-Solé Albert, Ruescas Arantxa, Bonanad Clara, Núñez Julio. Combining Disability and Frailty in an Integrated Scale for Prognostic Assessment After Acute Coronary Syndrome. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 2019;72(5):430–431. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sujino Y, Tanno J, Nakano S, Funada S, Hosoi Y, Senbonmatsu T, Nishimura S. Impact of hypoalbuminemia, frailty, and body mass index on early prognosis in older patients (>/=85 years) with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiol. 2015;66(3):263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White HD, Westerhout CM, Alexander KP, Roe MT, Winters KJ, Cyr DD, Fox KA, Prabhakaran D, Hochman JS, Armstrong PW, et al. Frailty is associated with worse outcomes in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from the TaRgeted platelet inhibition to cLarify the optimal strateGy to medicallY manage acute coronary syndromes (TRILOGY ACS) trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5(3):231–242. doi: 10.1177/2048872615581502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alegre O, Formiga F, Lopez-Palop R, Marin F, Vidan MT, Martinez-Selles M, Carol A, Sionis A, Diez-Villanueva P, Aboal J, et al. An easy assessment of frailty at baseline independently predicts prognosis in very elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(4):296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirill IP, Svetlana GG, Andrey NI, Olga AO, Alexey VK. Prediction of frailty impact on the results of treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Pharm Res. 2017;11(10):1242–6.

- 23.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(8):1487–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veronese N, Cereda E, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Luchini C, Manzato E, Sergi G, Manu P, Harris T, Fontana L, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in frail and pre-frail older adults: results from a meta-analysis and exploratory meta-regression analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;35:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart R. Cardiovascular disease and frailty: what are the mechanistic links? Clin Chem. 2019;65(1):80–86. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.287318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ungvari Z, Csiszar A. The emerging role of IGF-1 deficiency in cardiovascular aging: recent advances. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(6):599–610. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou L, Guo J, Xu F, Weng X, Yue W, Ge J. Cardiomyocyte dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase1 attenuates left-ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction: involvement in oxidative stress and apoptosis. Basic Res Cardiol. 2018;113(4):28. doi: 10.1007/s00395-018-0685-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu X, He L, Chen F, He X, Cai Y, Zhang G, Yi Q, He M, Luo J. Impaired autophagy contributes to adverse cardiac remodeling in acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maubaret CG, Salpea KD, Jain A, Cooper JA, Hamsten A, Sanders J, Montgomery H, Neil A, Nair D, Humphries SE, et al. Telomeres are shorter in myocardial infarction patients compared to healthy subjects: correlation with environmental risk factors. J Mol Med. 2010;88(8):785–794. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0624-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malkin CJ, Prakash R, Chew DP. The impact of increased age on outcome from a strategy of early invasive management and revascularisation in patients with acute coronary syndromes: retrospective analysis study from the ACACIA registry. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000540. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damman P, Clayton T, Wallentin L, Lagerqvist B, Fox KA, Hirsch A, Windhausen F, Swahn E, Pocock SJ, Tijssen JG, et al. Effects of age on long-term outcomes after a routine invasive or selective invasive strategy in patients presenting with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a collaborative analysis of individual data from the FRISC II - ICTUS - RITA-3 (FIR) trials. Heart. 2012;98(3):207–213. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bauer T, Koeth O, Junger C, Heer T, Wienbergen H, Gitt A, Zahn R, Senges J, Zeymer U. Acute coronary syndromes registry I: effect of an invasive strategy on in-hospital outcome in elderly patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(23):2873–2878. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llao I, Ariza-Sole A, Sanchis J, Alegre O, Lopez-Palop R, Formiga F, Marin F, Vidan MT, Martinez-Selles M, Sionis A, et al. Invasive strategy and frailty in very elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes. EuroIntervention. 2018;14(3):e336–e342. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunez J, Ruiz V, Bonanad C, Minana G, Garcia-Blas S, Valero E, Nunez E, Sanchis J. Percutaneous coronary intervention and recurrent hospitalizations in elderly patients with non ST-segment acute coronary syndrome: the role of frailty. Int J Cardiol. 2017;228:456–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267–315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mischie AN, Andrei CL, Sinescu C, Bajraktari G, Ivan E, Chatziathanasiou GN, Schiariti M. Antithrombotic treatment tailoring and risk score evaluation in elderly patients diagnosed with an acute coronary syndrome. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(7):442–456. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sergi G, Veronese N, Fontana L, De Rui M, Bolzetta F, Zambon S, Corti MC, Baggio G, Toffanello ED, Crepaldi G, et al. Pre-frailty and risk of cardiovascular disease in elderly men and women: the pro.V.a. study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(10):976–983. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell SP, Orr NM, Dodson JA, Rich MW, Wenger NK, Blum K, Harold JG, Tinetti ME, Maurer MS, Forman DE. What to expect from the evolving field of geriatric cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1286–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jimenez-Navarro MF, Lopez-Jimenez F, Perez-Belmonte LM, Lennon RJ, Diaz-Melean C, Rodriguez-Escudero JP, Goel K, Crusan D, Prasad A, Squires RW, et al. Benefits of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006404. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Paddon-Jones D, Rasmussen BB. Dietary protein recommendations and the prevention of sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12(1):86–90. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32831cef8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Text S1: MOOSE Checklist. Text S2: Search Strategy. (DOC 63 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.