Abstract

Background

For adipose-derived stromal cells (ASCs) to be safe for use in the clinical setting, they need to be prepared using good manufacturing practices (GMPs). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), used to expand ASCs in vitro in some human clinical trials, runs the risk of xenoimmunization and zoonotic disease transmission. To ensure that GMP standards are maintained, pooled human platelet lysate (pHPL) has been used as an alternative to FBS. ASCs proliferate more rapidly in pHPL than in FBS, with no significant change in immunophenotype and differentiation capacity. However, not much is known about how pHPL affects the transcriptome of these cells.

Methods

This study investigated the effect of pHPL and FBS on the ASC transcriptome during in vitro serial expansion from passage 0 to passage 5 (P0 to P5). RNA was isolated from ASCs at each passage and hybridized to Affymetrix HuGene 2.0 ST arrays for gene expression analysis.

Results

We observed that the transcriptome of ASCs expanded in pHPL (pHPL-ASCs) and FBS (FBS-ASCs) had the greatest change in gene expression at P2. Gene ontology revealed that genes upregulated in pHPL-ASCs were enriched for cell cycle, migration, motility, and cell-cell interaction processes, while those in FBS-ASCs were enriched for immune response processes. ASC transcriptomes were most homogenous from P2 to P5 in FBS and from P3 to P5 in pHPL. FBS- and pHPL-gene-specific signatures were observed, which could be used as markers to identify cells previously grown in either FBS or pHPL for downstream clinical/research applications. The number of genes constituting the FBS-specific effect was 3 times greater than for pHPL, suggesting that pHPL may be a milder supplement for cell expansion. A set of genes were expressed in ASCs at all passages and in both media. This suggests that a unique ASC in vitro transcriptomic profile exists that is independent of the passage number or medium used.

Conclusions

GO classification revealed that pHPL-ASCs are more involved in cell cycle processes and cellular proliferation when compared to FBS-ASCs, which are involved in more specialized or differentiation processes like cardiovascular and vascular development. This makes pHPL a potential superior supplement for expanding ASCs as they retain their proliferative capacity, remain untransformed and pHPL does not affect the genes involved in differentiation in specific developmental processes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13287-019-1370-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adipose-derived stromal cells, Pooled human platelet lysate, Fetal bovine serum, Transcriptome

Background

Adipose-derived stromal cells (ASCs) could constitute a novel therapeutic option for the treatment of several diseases and are increasingly being assessed in clinical trials for this purpose [1–3]. Most clinical trials make use of ASCs that have been expanded ex vivo via several rounds of passaging in order to obtain adequate cell numbers [4, 5]. In the laboratory, ASCs are traditionally expanded in medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS); however, it has been reported that ASCs expanded in FBS cause immune reactions when given to human patients [2, 6–8]. However, for these cells to be considered safe for patient use, they need to adhere to good manufacturing processes (GMPs), in which non-defined and animal-related products are eliminated [2, 9]. As a result, several investigators have moved away from using FBS and have instead investigated the use of human alternatives such as pooled human platelet lysate (pHPL) [10–12]. Most studies compare the criteria as set out by the Mesenchymal and Tissue Stem Cell Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) and International Federation of Adipose Therapeutics and Sciences (IFATS) when comparing FBS to pHPL [6, 10, 13–15]. These criteria include ASC adherence to plastic, immunophenotypic surface marker expression and the ability to differentiate into bone, fat, and cartilage [5, 13]. The use of pHPL as a medium supplement has advantages over FBS. It has thus been reported that when the cells are expanded in pHPL, their innate characteristics are unaltered and proliferation is increased during expansion [10, 12, 16]. However, it is well known that experimental conditions, such as medium supplementation, can have an effect on gene expression [15, 17–19]. It is therefore important to demonstrate that the cells are safe for use in patients by measuring the effect of the medium supplementation at the level of gene expression. In this study, we assessed the changes in ASC gene expression that occur during serial passaging by comparing cells expanded in FBS versus pHPL.

Material and methods

ASC isolation and expansion

Lipoaspirate samples were collected from five individual patients undergoing elective liposuction. Stromal vascular fraction (SVF) was isolated from lipoaspirates using previously established protocols [5, 20]. SVF containing ASCs was seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells/cm2 in T80 flasks (80 cm2; NUNC™, Roskilde Site, Kamstrupvej, Denmark) and maintained in α-MEM containing 2% (v/v) penicillin [10,000 U/mL]-streptomycin [10,000 8 μg/mL] (p/s; GIBCO, Life Technologies™, New York, USA) and either 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; GIBCO, Life Technologies™, New York, USA) or 10% pooled human platelet lysate (pHPL) supplemented with preservative-free heparin ([2 U/mL]; Biochrom, Merck Millipore, Berlin, Germany). pHPL was manufactured as previously described in our laboratory and subjected to quality control checks [21, 22]. At 80 to 90% confluence, ASCs were dissociated using trypLE (Life Technologies™, New York, USA) and counted. ASCs at passage zero (P0) were expanded by plating 5 × 103 cells/cm2 into T80 flasks and were maintained in α-MEM containing 2% (v/v) p/s and either 10% (v/v) pHPL or 10% (v/v) FBS at 37 °C in 5% CO2. The passaging process was repeated from P0 to P5 for ASCs expanded in FBS and pHPL. ASCs were analyzed at every passage as shown on the schematic experimental design (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

ASC characterization

ASCs were characterized by surface marker expression (immunophenotype) and the ability to differentiate into adipocytes. Immunophenotype was assessed on SVF and at each passage (P0 to P5) using methods previously described [22]. ASCs were induced to differentiate into adipocytes at P5, and adipogenesis was measured using methods previously described [17, 22]. Data and experimental design (Additional file 1: Figure S1) can be found in Additional file 1.

RNA isolation and quality

ASCs were expanded in FBS or pHPL and RNA was isolated at each passage. At confluence, the cells were dissociated using trypLE and counted. Thereafter, 1 × 106 cells were centrifuged (300g) and the resultant pellet was washed using phosphate buffered saline (PBS). RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and quantified on a NanoDrop® ND 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA purity was assessed at an absorbance optical density (OD) ratio of 260/280 and 260/230. RNA integrity and quality were assessed using a TapeStation® 2200 (Agilent Technologies; Santa Clara, CA, USA) together with RNA ScreenTape® and Sample Buffer kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sample read-out was compared to a TapeStation® RNA ladder. RNA that had absorbance OD ratios greater than 2 and RIN values greater than 8 was used for downstream applications.

Microarray gene expression analysis

Total RNA (100 ng) isolated from ASCs expanded in FBS or pHPL from P0 to P5 was used for first- and second-strand cDNA syntheses, followed by the synthesis and amplification of complementary RNA (cRNA) by in vitro transcription using an Affymetrix GeneChip® WT PLUS Reagent Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplified cRNA was purified using magnetic purification beads. Thereafter, 15 μg of purified cRNA was used to synthesize second cycle single-stranded cDNA (ss-cDNA) and subsequently followed by another purification step. Purified ss-cDNA (5.5 μg) was fragmented, labeled, and used to prepare a hybridization cocktail. Hybridization was performed using the Affymetrix GeneChip® Hybridization Wash and Stain Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The hybridization cocktail was hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip® Human Gene 2.0 ST arrays. Arrays were placed in an Affymetrix GeneChip® Hybridization Oven-645 rotating at 60 rpm at 45 °C for 17 h, after which they were washed and stained in an Affymetrix GeneChip® Fluidics Station-450Dx before being scanned in an Affymetrix GeneChip® Scanner-7G. The output Affymetrix CEL files, which have intensity values for all probes present on the scanned arrays, were used for further analysis. The Robust Multiarray Analysis algorithm [23] in the Affymetrix Expression Console™ was used to perform background correction, summarization, normalization, and the calculation of probe set expression values. Finally, the Affymetrix Transcription Analysis Console™ was used to calculate the fold change of each probe set or transcript cluster identifier number and mapped to the corresponding gene. Only differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that had a fold-change ≥ 2 or ≤ − 2, a p value > 0.05, and an FDR > 0.5 were used for downstream analysis. The fold-change of each gene represents the change in gene expression seen between two samples or conditions being compared and is based on the signal measured.

Functional analysis

The DEGs for the different samples were used for functional analysis to determine significantly enriched pathways and processes using the g:GOSt functional enrichment analysis tool on the g:Profiler web server [24].

Results

ASC characterization

pHPL-ASCs had a tighter, smaller elongated shape when compared to FBS-ASCs (Additional file 1: Figure S2). The immunophenotype of FBS-ASCs and pHPL-ASCs was determined at each passage. More than 90% had the expression profile CD44+CD45−CD73+CD90+CD105+, while fewer than 2% were CD31+CD73−CD105−, and this was maintained up to P5 (Additional file 1: Figure S3). FBS-ASCs and pHPL-ASCs both underwent adipogenesis as evidenced by the accumulation of lipid droplets (Additional file 1: Figure S4).

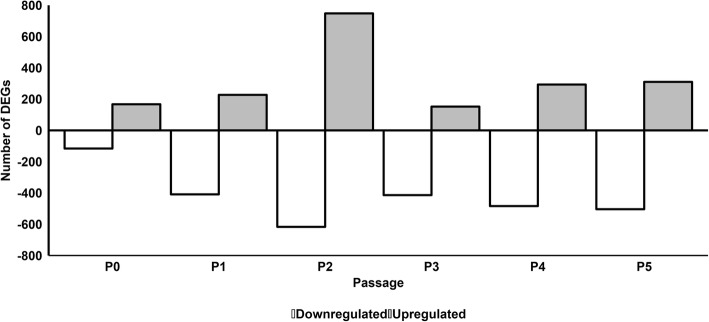

Gene expression analysis of ASCs expanded in pHPL and FBS

To compare at the effect of pHPL versus FBS on the transcriptome, we performed a microarray analysis of gene expression on ASCs serially expanded in pHPL or FBS from P0 to P5. We found that 185, 256, 811, 171, 319, and 349 genes were significantly upregulated while 127, 457, 707, 457, 575, and 567 genes were significantly downregulated in ASCs expanded in pHPL (pHPL-ASCs) compared to FBS (FBS-ASCs) at P0, P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5 respectively (Fig. 1; Additional file 1: Figure S5 and Additional file 2).

Fig. 1.

Number of differentially expressed genes in pHPL-ASCs compared to FBS-ASCs at each passage. The gray and white bars represent up- and downregulated genes respectively in pHPL-ASCs when compared to FBS-ASCs at each passage. Volcano plots for these DEGs can be found in Additional file 1: Figure S5)

Functional analysis of the DEGs by gene ontology (GO) classification revealed that genes that were significantly upregulated at the different passages were enriched for certain biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC) and molecular functions (MF). Only the top 5 significant GO terms will be discussed here. From P0 to P5, pHPL-ASCs were enriched for GO terms such as developmental processes, cell cycle processes, cellular proliferation, and extracellular matrix and structure organization. FBS-ASCs were enriched for GO terms such as cell proliferation, adhesion, extracellular matrix and structure organization, cardiovascular and vascular development, structure morphogenesis, and other developmental processes (Table 1; Additional file 3).

Table 1.

Top 5 enriched GO terms for pHPL-ASCs (upregulated) and FBS-ASCs (downregulated) at each passage (P0–P5). Related to Fig. 1

| Gene expression | Domain | P0 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | BP | Regulation of cell proliferation | Extracellular matrix organization | Cell cycle process | Anatomical structure development | Animal organ development | Multicellular organism development |

| Cellular developmental process | Extracellular structure organization | Cell cycle | Multicellular organism development | Multicellular organism development | Extracellular structure organization | ||

| System development | Multicellular organism development | Chromosome organization | System development | System development | Extracellular matrix organization | ||

| Regulation of developmental process | Anatomical structure development | Mitotic cell cycle process | Developmental process | Tissue development | Anatomical structure development | ||

| Multicellular organism development | System development | Mitotic cell cycle | Animal organ development | Anatomical structure development | System development | ||

| CC | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Chromosome | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | |

| Extracellular matrix | Extracellular matrix | Chromosomal part | Extracellular matrix | Extracellular matrix | Extracellular matrix | ||

| Extracellular region | Extracellular region | Chromosomal region | Extracellular region part | Focal adhesion | Extracellular region part | ||

| Extracellular region part | Extracellular region part | Nuclear lumen | Striated muscle thin filament | Cell-substrate adherens junction | Collagen trimer | ||

| Extracellular space | Extracellular space | Non-membrane-bounded organelle | Muscle thin filament tropomyosin | Cell-substrate junction | Extracellular region | ||

| MF | Glycosaminoglycan binding | mRNA binding involved in posttranscriptional gene silencing | Protein binding | mRNA binding involved in posttranscriptional gene silencing | Oxidoreductase activity, oxidizing metal ions | Transcription factor activity, RNA polymerase ii core promoter proximal region sequence-specific binding | |

| Ion binding | Collagen binding | Catalytic activity, acting on DNA | mRNA binding | Metalloendopeptidase activity | Metalloendopeptidase activity | ||

| Platelet-derived growth factor-activated receptor activity | Extracellular matrix structural constituent | Carbohydrate derivative binding | Growth factor binding | [heparan sulfate]-glucosamine 3-sulfotransferase 3 activity | Metal ion binding | ||

| Heparin binding | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor binding | Adenyl ribonucleotide binding | Transforming growth factor beta-activated receptor activity | Ionotropic glutamate receptor binding | Cation binding | ||

| Sulfur compound binding | Ion binding | Adenyl nucleotide binding | Oxidoreductase activity, oxidizing metal ions, NAD or NADP as acceptor | Metallopeptidase activity | Xylosyltransferase activity | ||

| Downregulated | BP | Cell proliferation | Biological adhesion | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | Cell adhesion | Regulation of multicellular organismal process |

| Anatomical structure morphogenesis | Cell adhesion | Multicellular organismal process | Developmental process | Biological adhesion | Developmental process | ||

| Circulatory system development | Multicellular organism development | System development | Vasculature development | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | Anatomical structure development | ||

| Extracellular structure organization | Anatomical structure development | Cell adhesion | Cardiovascular system development | Signaling | Multicellular organism development | ||

| Extracellular matrix organization | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | Developmental process | Anatomical structure development | Regulation of multicellular organismal process | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | ||

| CC | Extracellular region part | Extracellular region | Extracellular region part | Extracellular region part | Extracellular region part | Extracellular region part | |

| Extracellular space | Extracellular region part | Extracellular region | Extracellular region | Extracellular region | Extracellular region | ||

| Extracellular matrix | Cell periphery | Extracellular space | Extracellular space | Extracellular space | Extracellular space | ||

| Extracellular matrix component | Plasma membrane part | Extracellular matrix | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Extracellular matrix | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | ||

| Integral component of plasma membrane | Cell surface | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Extracellular matrix | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Extracellular matrix | ||

| MF | Insulin-like growth factor binding | Cell adhesion molecule binding | Growth factor binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | |

| Collagen binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Receptor binding | Sulfur compound binding | Heparin binding | Sulfur compound binding | ||

| Protein-lysine 6-oxidase activity | Growth factor binding | Extracellular matrix structural constituent | Heparin binding | Sulfur compound binding | Receptor binding | ||

| Transition metal ion binding | Receptor binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Extracellular matrix structural constituent | Extracellular matrix structural constituent | Extracellular matrix structural constituent | ||

| Protein binding | Integrin binding | Insulin-like growth factor binding | Growth factor binding | Growth factor binding | Heparin binding |

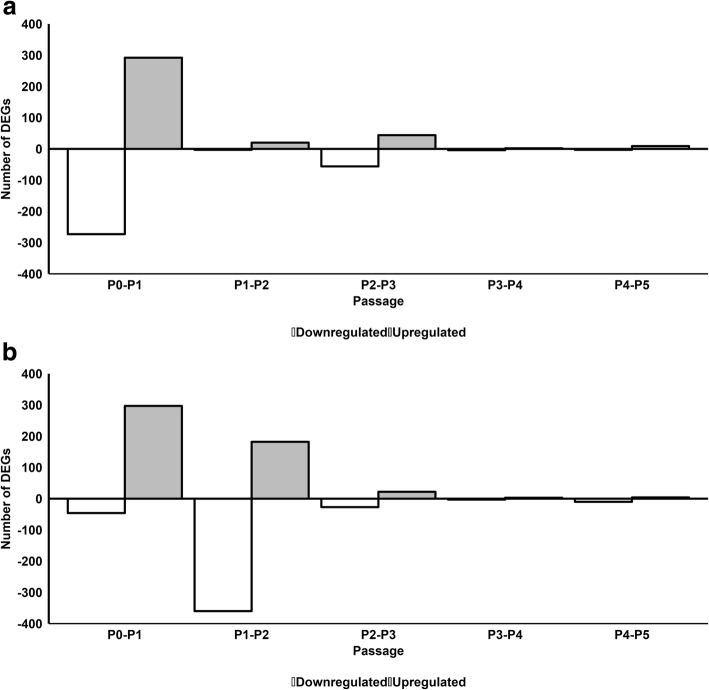

We next investigated the effect of serial passaging on gene expression in pHPL-ASCs and FBS-ASCs by comparing gene expression at each passage to that of the previous passage (P1 vs P0, P2 vs P1, P3 vs P2, P4 vs P3, and P5 vs P4). For FBS-ASCs, 292, 20, 44, 2, and 9 genes were significantly upregulated while 273, 3, 56, 4, and 3 genes were significantly downregulated from P0 to P5, respectively (Fig. 2a and Additional file 4). For pHPL-ASCs, 297,182, 22, 3, and 4 genes were significantly upregulated while 46, 360, 27, 3, and 4 genes were significantly downregulated from passages P0 to P5, respectively (Fig. 2b and Additional file 5).

Fig. 2.

Number of differentially expressed genes during serial passaging of FBS-ASCs (a) or pHPL-ASCs (b). Gray bars above the horizontal axis are upregulated genes and white bars below the horizontal axis are downregulated genes

GO classification of upregulated genes in FBS-ASCs revealed they were significantly enriched for cell migration and motility from P0 to P1, while those for P1 to P2 and P2 to P3 were mostly enriched for immunological responses and processes. Genes that were upregulated from P3 to P4 and P4 to P5 were not enriched for any GO terms (Table 2; Additional file 6). Genes that were downregulated from P0 to P1 and P1 to P2 were enriched for system and developmental processes, while those from P2 to P3 were enriched for immune subunit and protein assembly. In contrast, downregulated genes from P3 to P4 and P4 to P5 were not enriched for any GO terms.

Table 2.

Top 5 enriched GO terms for significantly up- and downregulated DEGs for FBS-ASCs between subsequent passages. Related to Fig. 2a

| Gene expression | Domain | P0–P1 | P1–P2 | P2–P3 | P3–P4 | P4–P5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | BP | Cell migration | Immune system process | Protein-carbohydrate complex subunit organization | – | – |

| Immune system process | Immune response | Polysaccharide assembly with MHC class II protein complex | – | – | ||

| Leukocyte migration | Defense response | Protein-carbohydrate complex assembly | – | – | ||

| Localization of cell | Response to stimulus | Antigen processing and presentation of polysaccharide antigen via MHC class II | – | – | ||

| Cell motility | Inflammatory response | MHC class II protein complex assembly | – | – | ||

| CC | Cell surface | Plasma membrane | MHC class II protein complex | – | – | |

| Plasma membrane | Cell periphery | Lumenal side of endoplasmic reticulum membrane | – | – | ||

| Cell periphery | Plasma membrane part | Integral component of lumenal side of endoplasmic reticulum membrane | – | – | ||

| Integral component of membrane | Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | MHC protein complex | – | – | ||

| Extracellular region | Integral component of plasma membrane | Crlf-clcf1 complex | – | – | ||

| MF | Receptor binding | Receptor binding | MHC class II receptor activity | – | – | |

| Chemokine activity | Receptor activity | MHC class II protein complex binding | – | – | ||

| Receptor activity | Molecular transducer activity | MHC protein complex binding | – | – | ||

| Cytokine activity | Peptide antigen binding | Peptide antigen binding | – | – | ||

| Molecular transducer activity | Chemokine activity | Leptomycin b binding | – | – | ||

| Downregulated | BP | System development | Multicellular organism development | Protein-carbohydrate complex subunit organization | Spliceosomal complex disassembly | – |

| Multicellular organism development | System development | Polysaccharide assembly with MHC class II protein complex | Ribonucleoprotein complex disassembly | – | ||

| Developmental process | Anatomical structure development | Protein-carbohydrate complex assembly | – | – | ||

| Anatomical structure development | Developmental process | Antigen processing and presentation of polysaccharide antigen via MHC class II | – | – | ||

| Tissue development | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | MHC class II protein complex assembly | – | – | ||

| CC | Vesicle | Extracellular region part | MHC class II protein complex | U2-type post-mRNA release spliceosomal complex | – | |

| Extracellular region | Extracellular region | Lumenal side of endoplasmic reticulum membrane | Post-mRNA release spliceosomal complex | – | ||

| Extracellular region part | Extracellular space | Integral component of lumenal side of endoplasmic reticulum membrane | U2-type spliceosomal complex | – | ||

| Extracellular space | Cell periphery | MHC protein complex | – | – | ||

| Cell periphery | Plasma membrane | Crlf-clcf1 complex | – | – | ||

| MF | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Cell adhesion molecule binding | MHC class II receptor activity | – | – | |

| Cell adhesion molecule binding | Receptor binding | MHC class II protein complex binding | – | – | ||

| Heparin binding | Cadherin binding | MHC protein complex binding | – | – | ||

| Sulfur compound binding | Heparin binding | Peptide antigen binding | – | – | ||

| Fibronectin binding | Growth factor binding | Leptomycin b binding | – | – |

For pHPL-ASCs, GO terms significantly enriched for in upregulated genes were immune responses from P0 to P1, regulation of developmental processes and stimulus responses from P1 to P2, RNA binding regulation and transcription factor activity from P2 to P3 and regulation of cardiovascular processes from P3 and P4. Genes that were upregulated from P4 to P5 were not enriched for any GO term (Table 3; Additional file 7). Genes that were downregulated from P1 to P2 were significantly enriched for cell cycle processes, from P2 to P3 for cardiovascular processes, while downregulated genes from P0 to P1, P3 to P4, and P4 to P5 were not enriched for any GO term.

Table 3.

Top 5 enriched GO terms for significantly up- and downregulated DEGs for pHPL-ASCs between subsequent passages. Related to Fig. 2b

| Gene expression | Domain | P0–P1 | P1–P2 | P2–P3 | P3–P4 | P4–P5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | BP | Immune system process | Regulation of multicellular organismal process | Latent virus replication | Positive regulation of heart rate by epinephrine-norepinephrine | – |

| Immune response | Regulation of multicellular organismal development | Regulation of RNA binding transcription factor activity | Positive regulation of heart rate by epinephrine | – | ||

| Inflammatory response | Animal organ morphogenesis | Modulation by host of viral RNA-binding transcription factor activity | Regulation of blood pressure | – | ||

| Defense response | Response to external stimulus | Modulation by host of RNA binding by virus | Positive regulation of stress fiber assembly | – | ||

| Cell surface receptor signaling pathway | Inflammatory response | Regulation of DNA strand elongation | Negative regulation of smooth muscle cell migration | – | ||

| CC | Plasma membrane part | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Chloride channel complex | Muscle thin filament tropomyosin | – | |

| Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | Extracellular matrix | Alpha DNA polymerase:primase complex | Striated muscle thin filament | – | ||

| Integral component of plasma membrane | Extracellular region | Ion channel complex | Sarcoglycan complex | – | ||

| Plasma membrane | Extracellular region part | Transmembrane transporter complex | Bleb | – | ||

| Cell surface | Extracellular space | DNA replication factor a complex | Filamentous actin | – | ||

| MF | Receptor activity | Receptor binding | Chloride channel activity | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase activity | – | |

| Molecular transducer activity | Integrin binding | Anion channel activity | Actin binding | – | ||

| Signal transducer activity | Calcium ion binding | Chloride transmembrane transporter activity | N-Acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase activity | – | ||

| Signaling receptor activity | Sulfur compound binding | Alkylglycerophosphoethanolamine phosphodiesterase activity | Structural constituent of muscle | – | ||

| Chemokine activity | Scavenger receptor activity | Inorganic anion transmembrane transporter activity | Arylsulfatase activity | – | ||

| Downregulated | BP | – | Cell cycle | Positive regulation of heart rate by epinephrine-norepinephrine | – | – |

| – | Cell cycle process | Positive regulation of heart rate by epinephrine | – | – | ||

| – | Chromosome organization | Regulation of blood pressure | – | – | ||

| – | Mitotic cell cycle | Positive regulation of stress fiber assembly | – | – | ||

| – | Mitotic cell cycle process | Negative regulation of smooth muscle cell migration | – | – | ||

| CC | – | Chromosome | Muscle thin filament tropomyosin | – | – | |

| – | Chromosomal part | Striated muscle thin filament | – | – | ||

| – | Chromosomal region | Sarcoglycan complex | – | – | ||

| – | Intracellular non-membrane-bounded organelle | Bleb | – | – | ||

| – | Non-membrane-bounded organelle | Filamentous actin | – | – | ||

| MF | – | Protein binding | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase activity | – | – | |

| – | Catalytic activity, acting on DNA | Actin binding | – | – | ||

| – | Adenyl ribonucleotide binding | N-Acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase activity | – | – | ||

| – | ATP binding | Structural constituent of muscle | – | – | ||

| – | Adenyl nucleotide binding | Arylsulfatase activity | – | – |

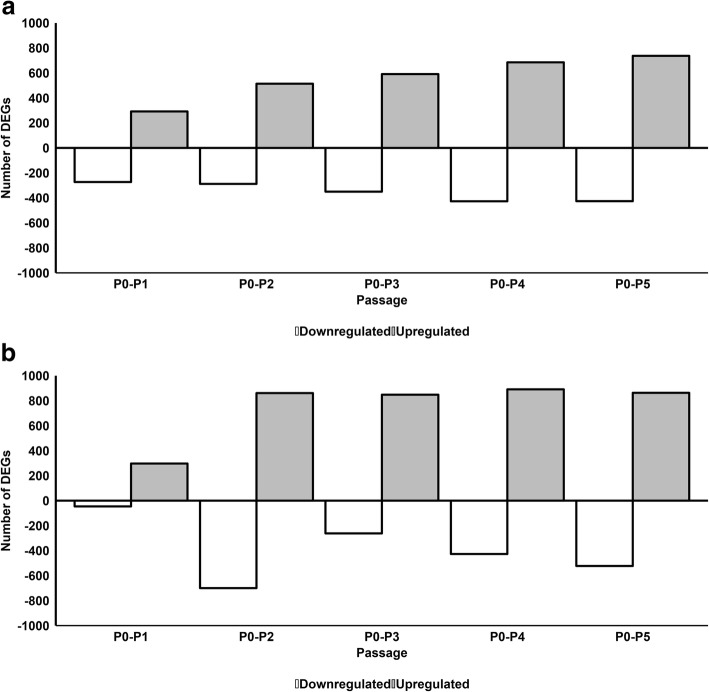

We next undertook to evaluate the extent to which the ASC transcriptome at each passage (P1 through to P5) differs from its original state (SVF) at P0 when expanded in either FBS or pHPL, and to functionally characterize such changes using GO classification. This was done by comparing gene expression at each passage (P1 to P5) to that of the “original” seeded ASCs (SVF) at P0. For FBS-ASCs, 292, 514, 591, 685, and 737 genes were significantly upregulated while 273, 288, 350, 427, and 426 genes were significantly downregulated from P1 to P5 (Fig. 3a and Additional file 8). For pHPL-ASCs, 297, 861, 848, 891, and 863 genes were significantly upregulated while 46, 700, 262, 427, and 523 genes were significantly downregulated from passage P1 to P5 (Fig. 3b and Additional file 9).

Fig. 3.

Number of differentially expressed genes when compared to P0 in FBS-ASCs (a) or pHPL-ASCs (b). Gray bars above the horizontal axis are upregulated genes and white bars below the horizontal axis are downregulated genes

GO terms significantly enriched for in upregulated genes at each passage (P1 to P5) when compared to P0 in FBS-ASCs (Table 4; Additional file 10) or pHPL-ASCs (Table 5; Additional file 11) were specific to immune responses and processes. GO terms specific to developmental processes were enriched for in the downregulated genes in FBS-ASCs at each passage (P1 to P5) when compared to P0 (Table 4; Additional file 10). For pHPL-ASCs, downregulated genes at P1 were not enriched for any GO term, while those of all the subsequent passages (P2 to P5) were enriched for cell cycle processes and developmental processes.

Table 4.

Top 5 enriched GO terms for significantly up- and downregulated DEGs for FBS-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages. Related to Fig. 3a

| Gene expression | Domain | P0–P1 | P0–P2 | P0–P3 | P0–P4 | P0–P5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | BP | Cell migration | Immune system process | Immune system process | Immune system process | Immune system process |

| Immune system process | Immune response | Defense response | Immune response | Immune response | ||

| Leukocyte migration | Defense response | Immune response | Cell surface receptor signaling pathway | Defense response | ||

| Localization of cell | Regulation of immune system process | Inflammatory response | Response to stimulus | Response to stimulus | ||

| Cell motility | Cell surface receptor signaling pathway | Response to stimulus | Defense response | Cell surface receptor signaling pathway | ||

| CC | Cell surface | Plasma membrane | Plasma membrane | Plasma membrane part | Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | |

| Plasma membrane | Cell periphery | Cell periphery | Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | Plasma membrane | ||

| Cell periphery | Plasma membrane part | Plasma membrane part | Integral component of plasma membrane | Plasma membrane part | ||

| Integral component of membrane | Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | Plasma membrane | Integral component of plasma membrane | ||

| Extracellular region | Integral component of plasma membrane | Integral component of plasma membrane | Cell periphery | Cell periphery | ||

| MF | Receptor binding | Receptor activity | Receptor activity | Receptor activity | Receptor binding | |

| Chemokine activity | Molecular transducer activity | Molecular transducer activity | Molecular transducer activity | Receptor activity | ||

| Receptor activity | Receptor binding | Chemokine activity | Receptor binding | Molecular transducer activity | ||

| Cytokine activity | Chemokine activity | Receptor binding | Peptide antigen binding | Peptide antigen binding | ||

| Molecular transducer activity | Chemokine receptor binding | Signaling receptor activity | Chemokine activity | Chemokine activity | ||

| Downregulated | BP | System development | Anatomical structure development | System development | Anatomical structure development | System development |

| Multicellular organism development | Multicellular organism development | Multicellular organism development | Developmental process | Developmental process | ||

| Developmental process | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | Cell adhesion | Multicellular organism development | Multicellular organism development | ||

| Anatomical structure development | Nervous system development | Biological adhesion | System development | Anatomical structure development | ||

| Tissue development | System development | Developmental process | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | ||

| CC | Vesicle | Extracellular region | Extracellular region part | Extracellular region part | Extracellular region part | |

| Extracellular region | Extracellular region part | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Extracellular region | Cell periphery | ||

| Extracellular region part | Cell periphery | Extracellular region | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | ||

| Extracellular space | Extracellular space | Extracellular matrix | Extracellular matrix | Extracellular region | ||

| Cell periphery | Extracellular matrix | Extracellular space | Extracellular space | Plasma membrane | ||

| MF | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Cell adhesion molecule binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Sulfur dioxygenase activity | Cell adhesion molecule binding | |

| Cell adhesion molecule binding | Neuropilin binding | Heparin binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Cadherin binding | ||

| Heparin binding | Transporter activity | Receptor binding | Heparin binding | Receptor binding | ||

| Sulfur compound binding | Cadherin binding | Sulfur compound binding | Cell adhesion molecule binding | Neuropilin binding | ||

| Fibronectin binding | Protein tyrosine kinase activator activity | Ion binding | Cadherin binding | Actin binding |

Table 5.

Top 5 enriched GO terms for significantly up- and downregulated DEGs for pHPL-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages. Related to Fig. 3b

| Gene expression | Domain | P0–P1 | P0–P2 | P0–P3 | P0–P4 | P0–P5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | BP | Immune system process | Immune system process | Immune system process | Immune system process | Immune system process |

| Immune response | Immune response | Immune response | Immune response | Immune response | ||

| Inflammatory response | Inflammatory response | Response to external stimulus | Response to external stimulus | Response to external stimulus | ||

| Defense response | Defense response | Defense response | Defense response | Defense response | ||

| Cell surface receptor signaling pathway | Cellular response to chemical stimulus | Cellular response to chemical stimulus | Inflammatory response | Cellular response to chemical stimulus | ||

| CC | Plasma membrane part | Extracellular region | Extracellular region | Extracellular region | Extracellular region | |

| Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | Extracellular region part | Plasma membrane | Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | Extracellular region part | ||

| Integral component of plasma membrane | Plasma membrane part | Cell periphery | Integral component of plasma membrane | Plasma membrane part | ||

| Plasma membrane | Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | Intrinsic component of plasma membrane | Plasma membrane part | Extracellular space | ||

| Cell surface | Extracellular space | Plasma membrane part | Extracellular region part | Plasma membrane | ||

| MF | Receptor activity | Receptor activity | Receptor activity | Receptor activity | Receptor binding | |

| Molecular transducer activity | Receptor binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Molecular transducer activity | Receptor activity | ||

| Signal transducer activity | Molecular transducer activity | Molecular transducer activity | Receptor binding | Molecular transducer activity | ||

| Signaling receptor activity | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Receptor binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | Glycosaminoglycan binding | ||

| Chemokine activity | Cytokine binding | Sulfur compound binding | Peptide binding | Signal transducer activity | ||

| Downregulated | BP | – | Cell cycle process | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | Cell cycle process | Cell cycle process |

| – | Cell cycle | Developmental process | Cell division | Cell division | ||

| – | Mitotic cell cycle | Anatomical structure development | Anatomical structure morphogenesis | Chromosome segregation | ||

| – | Mitotic cell cycle process | System development | Tissue development | Nuclear chromosome segregation | ||

| – | Chromosome organization | Tissue development | Mitotic cell cycle process | Sister chromatid segregation | ||

| CC | – | Chromosome | Plasma membrane raft | Spindle | Chromosome, centromeric region | |

| – | Chromosomal part | Postsynapse | Condensed chromosome outer kinetochore | Condensed chromosome, centromeric region | ||

| – | Chromosomal region | Caveola | Cytoskeleton | Spindle | ||

| – | Chromosome, centromeric region | Z disc | Mitotic spindle | Kinetochore | ||

| – | Nuclear lumen | Postsynaptic density | Condensed chromosome kinetochore | Condensed chromosome kinetochore | ||

| MF | – | Catalytic activity, acting on DNA | 2-Aminoadipate transaminase activity | Microtubule binding | ATP binding | |

| – | Protein binding | Protein-lysine 6-oxidase activity | Cell adhesion molecule binding | Adenyl ribonucleotide binding | ||

| – | DNA-dependent ATPase activity | Binding | Tubulin binding | Adenyl nucleotide binding | ||

| – | Chromatin binding | Kynurenine aminotransferase activity | Cytoskeletal protein binding | Microtubule binding | ||

| – | ATP binding | Kynurenine-oxoglutarate transaminase activity | Kinase activity | Cell adhesion molecule binding |

We observed during serial passaging that the ASC transcriptomic profile stabilizes (minimal change in DEGs between adjacent passage numbers) from P2 for FBS (Fig. 2a) and P3 for pHPL (Fig. 2b). This could mean that ASC cultures are more homogenous from P2 to P5 and from P3 to P5 when expanded in FBS and pHPL respectively.

From the list of DEGs obtained at each passage (P1 to P5) when compared to P0 for both the FBS- and pHPL-ASCs (Additional files 8 and 9), we observed that ASCs showed gene expression signatures that were unique at each passage (P1 to P5) which was independent of the medium supplementation (FBS or pHPL) used during in vitro expansion (Additional file 12). This unique passage-specific gene expression profile constitutes the DEGs that were common to both pHPL and FBS at each passage number. Equally, if the passage-specific gene expression profile (DEGs common to both FBS- and pHPL-ASCs at each passage) is excluded at each passage number, the remaining DEGs represent unique FBS-ASC and pHPL-ASC passage-specific gene expression profiles (Additional file 12).

Furthermore, by considering the unique FBS-ASC passage-specific gene expression profile at all passages (P1 to P5), there were 37 (AC007879.7, ADAMTS4, ADAMTS9, ALOX5, CCL11, CCL4, CHST1, CLEC5A, COL6A3, CRISPLD2, CTHRC1, DCHS1, DOCK4, FIBIN, GALNT15, HEPH, HEY2, IL3RA, MCTP1, MMP1, NPAS2, PALMD, PIM1, PLAU, PLAUR, PREX1, RGS1, SNAI1, SRPX2, SYTL2, TDO2, TEAD2, THEMIS2, TNC, TNFAIP8L1, WAS, and WSB1) and 81 (ADAMTS1, AHNAK2, ALDH7A1, ANKRD1, ANKRD37, ARHGAP29, ARSK, ASAP2, ATP10D, ATP8B1, BAMBI, BCHE, BMP4, BST1, C11orf87, CCND1, CDH6, COMP, COX7A1, DEPTOR, FAM155A, FAM180A, FAM65B, FGF9, GLRX, GPR133, GPRC5A, GREM1, GREM2, HAPLN1, HSPB6, IGFBP5, IGFBP6, IL1RAPL2, KCTD16, KRT14, KRT18, LIMCH1, LURAP1L, MANSC1, MKX, MYOZ2, NCKAP5, NDFIP2, NIPAL3, NLRP10, NOV, NPR3, NR3C2, NRK, NTRK3, OXTR, PAPSS2, PDE1A, PDE1C, PI16, PKP2, PPL, RCAN2, RGS7BP, RHOJ, ROR1, RP11-553 K8.5, RP11-760H22.2, RP11-818F20.5, SAMD12, SBSPON, SDPR, SEMA5A, SLC1A1, SMURF2, STS, SYPL2, TIAM2, TINAGL1, TMEM19, TNFRSF11B, USP53, VEPH1, WEE1, and WNT2) genes that were consistently up- or downregulated respectively at all passages (Additional file 13). This represents the set of genes that were differentially expressed in ASCs as a result of them being expanded in FBS irrespective of the cell passage number. This could be reflective of an FBS-specific effect on the ASC transcriptome (FBS-ASC-specific gene expression profile). Similarly, by looking at the unique pHPL-ASC passage-specific gene expression profile at all passages (P1 to P5), there were 32 (A2M, ABLIM1, ADAMTS1, ADCYAP1R1, C10orf10, CHI3L1, EVI2B, F13A1, FAM65B, FST, GALNT12, HLA-QA1, HLA-DQA2, IL18, IL33, JAG1, MGP, MIR548I2, MT1G, MYCBP2, NTRK2, PCDHB16, PCSK1, PRELP, PRG4, RARRES1, ROR1-AS1, SFRP4, SMPDL3A, THBD, TPRG1, and ZNF727P) and 11 (CDK15, CTHRC1, EHD3, MBOAT2, MIR199A2, MIR503, MIR503HG, NT5DC2, PALLD, PPP2R3A, and RP11-08B5.2) genes that were consistently up- or downregulated respectively at all passages (Additional file 13). This represents the set of genes that are differentially expressed in ASCs as a result of them being expanded in pHPL, irrespective of the cell passage number. This could be reflective of a pHPL-specific effect on the ASC transcriptome (pHPL-ASC-specific gene expression profile).

In total therefore, there were 118 DEGs that constituted the FBS-ASC-specific gene expression profile, which is almost 3 times more than the 43 DEGs of the pHPL-ASC-specific gene expression profile (Additional file 14). Functional analysis of the pHPL-ASC-specific gene expression signature by GO classification showed that neither up- nor downregulated genes were enriched for any biological process, while the FBS-ASC-specific gene expression signature showed upregulated genes that were significantly enriched for cell migration and cell movement processes, while the downregulated genes were significantly enriched for the regulation of cell communication, signal transduction and cell proliferation processes.

Since the passage-specific gene expression profile consists of the common genes expressed by both FBS- and pHPL-ASCs at each passage, the genes that are common to all these passage-specific profiles will then constitute an ASC gene expression profile that is not affected by medium supplementation or cell passage number. There are 69 upregulated genes (AIF1, APCDD1, APLN, APOC1, AQP9, BCL6B, C1orf162, C5AR1, CADM3, CCDC102B, CCR1, CD14, CD37, CD53, CD93, CDH5, CLEC7A, CLIC6, CPM, CSF1R, CSF2RA, CXCL16, CXCR4, CXorf36, ECSCR, ELMO1, ENPEP, FCER1G, FPR3, GMFG, GUCY1A3, HPGDS, IL18R1, ITGAM, ITGAX, KDR, KYNU, LAPTM5, LCP1, LCP2, LRRC25, LYVE1, MERTK, MGAT4A, NCF2, NCKAP1L, NOTCH3, OLFM2, PAG1, PECAM1, PILRA, PLTP, PLVAP, POM121L9P, PPBP, RAMP2, RNASE6, SCG2, SLC11A1, SLC16A10, SPARCL1, SPP1, TM4SF18, TMEM176B, TNFRSF1B, TREM1, TREM2, TYROBP, and VSIG4) and 5 downregulated genes (F2RL2, FGF5, GALNT5, RAB3B, and SLC9A7) that constitute this subset of genes that were consistently differentially expressed from P1 through to P5. This set of genes therefore represents a unique in vitro ASC transcriptome profile that was neither affected by medium supplementation nor cell passage number (Additional file 14). GO classification of these genes revealed that they are significantly enriched for normal cellular processes like response to stimulus and stress, defense, and inflammatory responses and vesicle-mediated transport.

Discussion

Adipose-derived stromal cells (ASCs) are being assessed for their safety and efficacy in numerous clinical trials [6, 14, 25]. Traditionally, these cells are expanded in medium containing FBS, which is known to have several disadvantages such as the transmission of zoonotic diseases and the stimulation of immune reactions in patients [26, 27]. This has been circumvented by changing from animal products to either clinical-grade, GMP-compliant, or human alternative products [28]. One such change has been to supplement culture medium with either serum-free media or human blood components. The use of different medium supplements has been well documented and all show comparable immunophenotypic profiles and differentiation capacities while having marked differences in proliferation capacity [6]. The advantage of pHPL over these alternatives lies largely in the ability to pool platelets from multiple donors. Furthermore, it has been shown that ASCs expanded in pHPL retain their immunophenotypic characteristics and their ability to differentiate into bone, cartilage and fat [2, 6, 16]. One of the biggest advantages of using pHPL for ASC expansion is the marked increase in proliferation, which in turn makes the time required for expansion to therapeutic numbers considerably shorter [12, 22]. However, not much is known about the effect of pHPL has on the transcriptome, proteome, and secretome of these cells, which may impact on the outcome of clinical trials. This study has made use of microarray technology to examine the effect of pHPL on the ASC transcriptome during serial expansion in vitro, by comparing gene expression patterns in cells serially expanded in FBS or pHPL from P0 to P5.

Overall, the transcriptome of ASCs expanded in pHPL or FBS was most different at P2, the point at which the maximum number of genes were differentially expressed (811 and 707, respectively; Fig. 1). Most genes that were upregulated in pHPL-ASC were significantly enriched for biological process such as cell cycle, cell division, and proliferation. This supports a previous study by Glovinski et al., in which changes in the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation and development were observed for ASCs expanded in pHPL [12]. This likewise confirms findings from other studies which have shown an increase in ASC proliferation in pHPL [16, 29]. For ASCs expanded in FBS, our findings are consistent with the observation that numerous genes involved in extracellular matrix formation are upregulated [30, 31].

It is well documented that ASCs are a heterogeneous population as revealed by differences in transcriptome, proteome, and secretome between subpopulations within the ASC mixture [32–34]. The initial subset of adherent cells seeded in culture (P0) is a heterogeneous population; after passaging and prolonged expansion, the population becomes more homogenous [35]. Work performed by several groups has shown that the heterogeneity of ASCs during the expansion process remains between subpopulations and between individual cells within the same subpopulation [32, 36, 37]. Furthermore, it has been established that serial passaging affects ASC gene expression profiles [29]. Global gene expression profiles could therefore be used as a tool to study ASC heterogeneity at different passages. The more homogenous the cultures are at different passages, the fewer the number of DEGs will be between them.

We have investigated the effect of serial passaging on the ASC transcriptome by comparing FBS-ASC and pHPL-ASC cultures at each passage to those of the previous passage. We observed that the transcriptome was relatively stable from P2 to P5 for cells expanded in FBS and from P3 to P5 for cells expanded in pHPL as is evident from the relatively low number of DEGs obtained between these passages. This suggests the ASC cultures become homogenous at the transcriptome level earlier in FBS (P2) than in pHPL (P3). Interestingly, the genes upregulated significantly in FBS-ASCs were enriched for biological processes involved in immune and inflammatory responses. These findings are similar to those reported by Kim et al., where genes involved in inflammatory and immune responses, and cell migration and homing [19], were upregulated in ASCs expanded in FBS. They further postulated that the upregulation of these genes was due to the high cell density at the time of cell harvesting and could be the reason why FBS-expanded ASCs might be effective in treating graft-vs-host disease and damaged tissues. On the other hand, human clinical trials that have made use of ASCs expanded in FBS have reported adverse immune responses in patients after administration [2, 6–8, 38]. This could be due to the upregulation of these inflammatory and immune response genes. Genes that were downregulated in ASCs expanded in FBS at early passages (P0 to P1) were enriched for biological processes involving tissue development. Other studies have reported similar findings [30] which may explain why differentiation into adipocytes is reduced at later passages [18, 39]. Surprisingly, genes that were upregulated in pHPL-ASCs at earlier passages were also enriched for immune and inflammatory response processes. This could be due to the presence of immune cells in the early passages and may not be related to the serum used. To further explore the possible presence of immune cells in early passages (P0), we compared each passage (P1 to P5) to P0. It was observed that upregulated genes were significantly enriched for immune and inflammatory responses irrespective of the supplementation used, while the downregulated genes were enriched for tissue developmental and cell cycle and division processes. To assess serum-specific transcriptional changes (where genes were differentially expressed based on the serum supplementation used), we normalized gene expression at all other passages to the passage at which the transcriptome stabilizes (P2 for FBS-ASCs and P3 for pHPL-ASCs). For FBS-ASCs, the upregulated genes were enriched for immune and inflammatory responses; this supports the findings obtained when we compared each passage to the previous passage and each passage to P0. This may suggest that FBS-ASCs express genes that are involved in immune reactions; however, the functional implications of this in clinical or in vivo settings will need to be explored further. Genes that were downregulated in FBS-ASCs were enriched for structure, organ, and tissue developmental processes suggesting that ASCs have greater differentiation potential at earlier passages such as P2. For ASCs expanded in pHPL, upregulated genes were enriched for DNA and RNA regulation processes, BMP pathway signaling, and cell cycle and cell division processes. These findings suggest that proliferation may not decrease with increased passaging as indicated by Shahdadfar et al. [15] and could provide therapeutic numbers more readily than other human alternatives and FBS.

ASCs showed passage and serum-specific gene expression profiles. The passage-specific gene expression profile which is comprised of the DEGs that are common to both pHPL and FBS at each passage might reflect the in vitro serial passaging effect on the ASC transcriptome. The serum-specific gene expression signature at each passage (P1 to P5) may be reflective of the FBS or pHPL effect on the ASC transcriptome at that time period in culture (passage number) during the serial expansion process.

There were 118 and 43 genes that were differentially expressed in ASCs throughout the serial expansion process in FBS and pHPL respectively. This might indicate an ASC transcriptome profile that is specific to the medium supplementation (FBS or pHPL) used during cell expansion, irrespective of passage number. Thus, a serum-specific signature could potentially be used to identify the medium supplement (FBS or pHPL) in which the cells were previously expanded. This in turn could inform decision making in terms of the downstream clinical/research applications of these cells. There were fewer DEGs obtained for the pHPL-ASC-specific gene expression signature (43 genes), which is 1/3 the number of DEGS observed in FBS-ASCs (118 genes). The pHPL-ASC-specific gene expression signature was not enriched for any biological processes unlike the FBS-ASC-specific expression signature. This could mean that pHPL has no significant effect on the ASC transcriptome during in vitro serial passaging and suggests that pHPL might be a better medium supplement than FBS for in vitro cell expansion. Furthermore, downregulated genes in the FBS-ASC-specific gene expression signature were enriched for cell proliferation processes. This supports the observation that ASCs grow slower in FBS when compared to cell-expanded pHPL.

Finally, we observed that ASCs have a unique in vitro transcriptome profile, which is independent of cell passage number and/or medium supplementation. This consists of a set of genes that are always expressed by ASCs in vitro at any given time in culture during the expansion process (P1 to P5). Interestingly, some of the genes constituting this unique in vitro ASC transcriptome have previously been reported to be expressed by ASCs. Thus, ASCs express CXCR4 and CCR1 at both protein and mRNA levels [40]. PECAM-1 has been reported to be expressed by ASCs especially during early passages [41, 42]. ITGAM is another gene shown to be expressed by ASCs at low levels up to P3, and exhibits greater than 70% isoform switching between experimental conditions [43]. CD53 and TREM1 have been reported recently as novel marker genes expressed by adipogenic progenitor preadipocyte cells and BCL6B by osteochondrogenic progenitor preadipocyte cells from mouse bone marrow [44]. Furthermore, a novel subpopulation of human adipose tissue-resident macrophages (ATMs) located in the interstitial spaces between adipocytes has been shown to express CD14, which upon culturing to P3 is lost, at which point the cells display an expression profile which is similar to ASCs [45]. Therefore, the expression of CD14 by ASCs in this study suggests the presence of a heterogeneous population of ASCs that contains this novel subpopulation of ATMs which persisted beyond P3 in culture.

The entire process of obtaining a product for clinical purposes should adhere to the GMP guidelines. The use pHPL for the expansion of ASCs in vitro is one of many steps required. In this study, we made use of defined, clinical-grade reagents and the expansion of the ASCs was performed under sterile conditions. Isolation and expansion of ASCs in a closed system to further reduce the risk of contamination would provide a robust clinical GMP-complaint process.

Conclusion

This study highlights differences in the transcriptome of ASCs expanded in pHPL versus FBS, which could be used to guide their application in the clinical setting. ASCs expanded in FBS were enriched for immune and inflammatory responses, whereas ASCs expanded in pHPL were enriched for cell cycle, proliferation, and cell division. Our findings suggest that the differentiation capacity of ASCs is likely to be greater at earlier passages and that ASCs expanded in pHPL are likely to retain their proliferative capacity during prolonged expansion. These findings also suggest pHPL may be a superior supplement for expanding ASCs to therapeutic numbers without influencing the expression of genes involved in differentiation of specific developmental processes. Furthermore, we found that even though ASCs expanded in pHPL had a greater proliferation capacity, they were not enriched for genes specific to transformation. While these findings provide novel insights into potential markers for ASCs, some of the individual genes and groups of genes mentioned in this study need to be further investigated. Finally, to further compliment these findings, we believe that the proteome and the secretome of ASCs expanded in pHPL or FBS should also be studied.

Additional files

ASC characterization methods and results and volcano plots of DEGs between ASCs expanded in FBS and pHPL. ASC morphology, immunophenotype and differentiation, results and materials and methods, and volcano plots of DEGs between ASCs expanded in FBS and pHPL. (DOCX 2659 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs serially expanded in FBS and pHPL. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for ASCs serially expanded in pHPL or FBS (P0 – P5). This data relates to Fig. 1. (XLSX 193 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs serially expanded in FBS and pHPL. Complete list of enriched GO terms for ASCs serially expanded in pHPL or FBS (P0 – P5). This data relates to Table 1. (XLSX 1017 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs expanded in FBS between subsequent passages. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for FBS-ASCs between subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P1 - P2, P2 - P3, P3 - P4, P4 - P5). This data relates to Fig. 2a. (XLSX 88 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs expanded in pHPL between subsequent passages. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for pHPL-ASCs between subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P1 - P2, P2 - P3, P3 - P4, P4 - P5). This data relates to Fig. 2b. (XLSX 58 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs expanded in FBS between subsequent passages. Complete list of enriched GO terms for FBS-ASCs between subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P1 - P2, P2 - P3, P3 - P4, P4 - P5). This data relates to Table 2. (XLSX 516 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs expanded in pHPL between subsequent passages. Complete list of enriched GO terms for pHPL-ASCs between subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P1 - P2, P2 - P3, P3 - P4, P4 - P5). This data relates to Table 3. (XLSX 349 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs expanded in FBS between P0 and subsequent passages. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for FBS-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P0 - P2, P0 - P3, P0 - P4, P0 - P5). This data relates to Fig. 3a. (XLSX 166 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs expanded in pHPL between P0 and subsequent passages. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for pHPL-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P0 - P2, P0 - P3, P0 - P4, P0 - P5). This data relates to Fig. 3b. (XLSX 206 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs expanded in FBS between P0 and subsequent passages. Complete list of enriched GO terms for FBS-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P0 - P2, P0 - P3, P0 - P4, P0 - P5). This data relates to Table 4. (XLSX 1145 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs expanded in pHPL between P0 and subsequent passages. Complete list of enriched GO terms for pHPL-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P0 - P2, P0 - P3, P0 - P4, P0 - P5). This data relates to Table 5. (XLSX 1289 kb)

FBS and pHPL-ASC passage specific gene expression profile. A complete list of genes comprising the FBS and pHPL-ASC passage specific gene expression profile. (XLSX 89 kb)

FBS and pHPL-ASC medium supplementation specific gene expression profile. A complete list of genes comprising the FBS and pHPL-ASC medium supplementation specific gene expression profile. (XLSX 67 kb)

ASC gene signature irrespective of cell passage number and/or media supplement used. A complete list of genes comprising the ASC gene signature irrespective of cell passage number and/or media supplement used. (XLSX 20 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. P. Coetzee (Head of Plastic Surgery, Steve Biko Academic Hospital) and Dr. D. Hoffman (private practice) for their assistance with sample collection, Stephen Marrs and the team at Heamotec (South Africa) for the consumables and donation of their equipment, and the South African National Blood Service (SANBS) for the blood products provided for the pHPL alternatives.

Abbreviations

- ASC

Adipose-derived stromal cell

- BP

Biological processes

- CC

Cellular components

- cRNA

Complementary RNA

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- DNA

Deoxyribose nucleic acid

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- FS

Forward Scatter

- GMP

Good manufacturing practices/processes

- GO

Gene ontology

- IFATS

International Federation of Adipose Therapeutics and Sciences

- ISCT

Mesenchymal and Tissue Stem Cell Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy

- MI

Molecular function

- OD

Optical density

- P

Passage

- p/s

Penicillin/streptomycin

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- pHPL

Pooled human platelet lysate

- ss-cDNA

Single-stranded cDNA

- SVF

Stromal vascular fraction

- α-MEM

Modified Eagle’s medium - alpha

Authors’ contributions

CD performed the in vitro experiments (isolation, expansion, and ASC characterization) and the RNA isolation. MAA performed the hybridization. CD and MAA performed the transcriptome analysis. CD, MAA, and MSP conceptualized, wrote, and edited the article. MSP obtained funding for the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the South African Medical Research Council University Flagship Project (SAMRC-RFA-UFSP-01-2013/STEM CELLS), the SAMRC Extramural Unit for Stem Cell Research and Therapy and the Institute for Cellular and Molecular Medicine of the University of Pretoria.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (and its additional files). The microarray data files of this study will be deposited in NCBI GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Signed informed consent was obtained prior to the procedure and approval for the study was granted by the University of Pretoria Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (approval number 421/2013).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Toyserkani Navid Mohamadpour, Jørgensen Mads Gustaf, Tabatabaeifar Siavosh, Jensen Charlotte Harken, Sheikh Søren Paludan, Sørensen Jens Ahm. Concise Review: A Safety Assessment of Adipose-Derived Cell Therapy in Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review of Reported Adverse Events. STEM CELLS Translational Medicine. 2017;6(9):1786–1794. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riis S, Zachar V, Boucher S, Vemuri MC, Pennisi CP, Fink T. Critical steps in the isolation and expansion of adipose-derived stem cells for translational therapy. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2015;17:1–11. doi: 10.1017/erm.2015.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gimble JM, Ray SP, Zanata F, Wade J, Khoobehi K, Wu X, et al. Adipose derived cells and tissues for regenerative medicine. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2016;acsbiomaterials.6b00261. Available from: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00261 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Dykstra JA, Facile T, Patrick RJ, Francis KR, Milanovich S, Weimer JM, et al. Concise review: fat and furious: harnessing the full potential of adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:1096–1108. doi: 10.1002/sctm.16-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, Huang J, Futrell JW, Katz AJ, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:211–228. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dessels C, Potgieter M, Pepper MS. Making the switch: alternatives to fetal bovine serum for adipose-derived stromal cell expansion. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2016;4:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2016.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundin M, Ringdén O, Sundberg B, Nava S, Götherström C, Le Blanc K. No alloantibodies against mesenchymal stromal cells, but presence of anti-fetal calf serum antibodies, after transplantation in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell recipients. Haematologica. 2007;92:1208–1215. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalu MM, McIntyre L, Pugliese C, Fergusson D, Winston BW, Marshall JC, et al. Safety of cell therapy with mesenchymal stromal cells (SafeCell): a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becherucci V, Piccini L, Casamassima S, Bisin S, Gori V, Gentile F, Ceccantini R, De Rienzo E, Bindi B, Pavan P, et al. Human platelet lysate in mesenchymal stromal cell expansion according to a GMP grade protocol: a cell factory experience. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Koellensperger E, Bollinger N, Dexheimer V, Gramley F, Germann G, Leimer U. Choosing the right type of serum for different applications of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells: influence on proliferation and differentiation abilities. Cytotherapy. 2014;16:789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trojahn Kølle S-F, Fischer-Nielsen A, Mathiasen AB, Elberg JJ, Oliveri RS, Glovinski PV, et al. Enrichment of autologous fat grafts with ex-vivo expanded adipose tissue-derived stem cells for graft survival: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1113–1120. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glovinski PV, Herly M, Mathiasen AB, Svalgaard JD, Borup R, Talman MLM, et al. Overcoming the bottleneck of platelet lysate supply in large-scale clinical expansion of adipose-derived stem cells: a comparison of fresh versus three types of platelet lysates from outdated buffy coat-derived platelet concentrates. Cytotherapy. 2017;19:222–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourin P, Bunnell BA, Casteilla L, Dominici M, Katz AJ, March KL, et al. Stromal cells from the adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction and culture expanded adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells: a joint statement of the International Federation for Adipose Therapeutics and Science (IFATS) and the International So. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riis S, Nielsen F, Pennisi C, Zachar V, Fink T. Comparative analysis of media and supplements on inititation and expansion of adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5:314–324. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahdadfar A, Frønsdal K, Haug T, Reinholt FP, Brinchmann JE. In vitro expansion of human mesenchymal stem cells: choice of serum is a determinant of cell proliferation, differentiation, gene expression, and transcriptome stability. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1357–1366. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trojahn Kølle S, Oliveri RS, Glovinski PV, Kirchhoff M, Mathiasen AB, Elberg JJ, et al. Pooled human lysate versus fetal bovine serum — investigating the proliferation rate , chromosome stability and angiogenic potential of human adipose tissueederived stem cells intended for clinical use. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:1086–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.01.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tratwal J, Follin B, Ekblond A, Kastrup J, Haack-Sørensen M. Identification of a common reference gene pair for qPCR in human mesenchymal stromal cells from different tissue sources treated with VEGF. BMC Mol Biol. 2014;15:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-15-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambele MA, Dessels C, Durandt C, Pepper MS. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression during adipogenesis in human adipose-derived stromal cells reveals novel patterns of gene expression during adipocyte differentiation. Stem Cell Res. 2016;16:725–734. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DS, Lee MW, Yoo KH, Lee T-H, Kim HJ, Jang IK, et al. Gene expression profiles of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells are modified by cell culture density. PLoS One. 2014;9:e83363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Vollenstee FA, Dessels C, Kallmeyer K, de Villiers D, Potgieter M, Durandt C, et al. Isolation and characterization of adipose-derived stromal cells. In: Van Pham P, et al., editors. Stem Cell Process. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. pp. 131–161. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schallmoser K, Strunk D. Generation of a pool of human platelet lysate and efficient use in cell culture. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;946:349–362. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-128-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dessels C, Durandt C, Pepper MS. Comparison of human platelet lysate alternatives using expired and freshly isolated platelet concentrates for adipose-derived stromal cell expansion. Platelets. 2018;00:1–12. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2018.1445840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reimand J, Arak T, Adler P, Kolberg L, Reisberg S, Peterson H, et al. G:profiler-a web server for functional interpretation of gene lists (2016 update) Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W83–W89. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kocaoemer A, Kern S, Klüter H, Bieback K, Kluter H. Human AB serum and thrombin-activated platelet-rich plasma are suitable alternatives to fetal calf serum for the expansion of mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1270–1278. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Der Valk J, Brunner D, De Smet K, Fex Svenningsen A, Honegger P, Knudsen LE, et al. Optimization of chemically defined cell culture media--replacing fetal bovine serum in mammalian in vitro methods. Toxicol Vitr. 2010;24:1053–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fink T, Lund P, Pilgaard L, Rasmussen JG, Duroux M, Zachar V. Instability of standard PCR reference genes in adipose-derived stem cells during propagation, differentiation and hypoxic exposure. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crespo-diaz R, Behfar A, Butler GW, Padley DJ, Sarr MG, Bartunek J, et al. Platelet lysate consisting of a natural repair proteome supports human mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and chromosomal stability. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:797–811. doi: 10.3727/096368910X543376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schallmoser K, Bartmann C, Rohde E, Bork S, Guelly C, Obenauf AC, et al. Replicative senescence-associated gene expression changes in mesenchymal stromal cells are similar under different culture conditions. Haematologica. 2010;95:867–874. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.011692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner W, Wein F, Seckinger A, Frankhauser M, Wirkner U, Krause U, et al. Comparative characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:1402–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho K-A, Park M, Kim Y-H, Woo S-Y, Ryu K-H. RNA sequencing reveals a transcriptomic portrait of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and palatine tonsils. Sci Rep. 2017;7:17114. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16788-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baer Patrick C., Geiger Helmut. Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells: Tissue Localization, Characterization, and Heterogeneity. Stem Cells International. 2012;2012:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2012/812693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perrini Sebastio, Ficarella Romina, Picardi Ernesto, Cignarelli Angelo, Barbaro Maria, Nigro Pasquale, Peschechera Alessandro, Palumbo Orazio, Carella Massimo, De Fazio Michele, Natalicchio Annalisa, Laviola Luigi, Pesole Graziano, Giorgino Francesco. Differences in Gene Expression and Cytokine Release Profiles Highlight the Heterogeneity of Distinct Subsets of Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells in the Subcutaneous and Visceral Adipose Tissue in Humans. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e57892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner W, Feldmann RE, Seckinger A, Maurer MH, Wein F, Blake J, et al. The heterogeneity of human mesenchymal stem cell preparations - evidence from simultaneous analysis of proteomes and transcriptomes. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruder SP, Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE. Growth kinetics, self-renewal, and the osteogenic potential of purified human mesenchymal stem cells during extensive subcultivation and following cryopreservation. J Cell Biochem. 1997;64:278–294. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(199702)64:2<278::AID-JCB11>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donnenberg Albert D., Meyer E. Michael, Rubin J. Peter, Donnenberg Vera S. The cell-surface proteome of cultured adipose stromal cells. Cytometry Part A. 2015;87(7):665–674. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Januszyk M, Rennert R, Sorkin M, Maan Z, Wong L, Whittam A, et al. Evaluating the effect of cell culture on gene expression in primary tissue samples using microfluidic-based single cell transcriptional analysis. Microarrays. 2015;4:540–550. doi: 10.3390/microarrays4040540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, et al. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: the International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:393–395. doi: 10.1080/14653240500319234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Safwani WKZW, Makpol S, Sathapan S, Chua K. Impact of adipogenic differentiation on stemness and osteogenic gene expression in extensive culture of human adipose-derived stem cells. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:597–606. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.43753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baek SJ, Kang SK, Ra JC. In vitro migration capacity of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells reflects their expression of receptors for chemokines and growth factors. Exp Mol Med. 2011;43:596–603. doi: 10.3858/emm.2011.43.10.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panina YA, Yakimov AS, Komleva YK, Morgun AV, Lopatina OL, Malinovskaya NA, et al. Plasticity of adipose tissue-derived stem cells and regulation of angiogenesis. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1656. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang SJ, Fu RH, Shyu WC, Liu SP, Jong GP, Chiu YW, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells: isolation, characterization, and differentiation potential. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:701–709. doi: 10.3727/096368912X655127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mieczkowska A, Schumacher A, Filipowicz N, Wardowska A, Zieliński M, Madanecki P, et al. Immunophenotyping and transcriptional profiling of in vitro cultured human adipose tissue derived stem cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11339. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29477-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ambrosi TH, Scialdone A, Graja A, Gohlke S, Jank A-M, Bocian C, et al. Adipocyte accumulation in the bone marrow during obesity and aging impairs stem cell-based hematopoietic and bone regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eto H, Ishimine H, Kinoshita K, Watanabe-Susaki K, Kato H, Doi K, et al. Characterization of human adipose tissue-resident hematopoietic cell populations reveals a novel macrophage subpopulation with CD34 expression and mesenchymal multipotency. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:985–997. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ASC characterization methods and results and volcano plots of DEGs between ASCs expanded in FBS and pHPL. ASC morphology, immunophenotype and differentiation, results and materials and methods, and volcano plots of DEGs between ASCs expanded in FBS and pHPL. (DOCX 2659 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs serially expanded in FBS and pHPL. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for ASCs serially expanded in pHPL or FBS (P0 – P5). This data relates to Fig. 1. (XLSX 193 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs serially expanded in FBS and pHPL. Complete list of enriched GO terms for ASCs serially expanded in pHPL or FBS (P0 – P5). This data relates to Table 1. (XLSX 1017 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs expanded in FBS between subsequent passages. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for FBS-ASCs between subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P1 - P2, P2 - P3, P3 - P4, P4 - P5). This data relates to Fig. 2a. (XLSX 88 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs expanded in pHPL between subsequent passages. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for pHPL-ASCs between subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P1 - P2, P2 - P3, P3 - P4, P4 - P5). This data relates to Fig. 2b. (XLSX 58 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs expanded in FBS between subsequent passages. Complete list of enriched GO terms for FBS-ASCs between subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P1 - P2, P2 - P3, P3 - P4, P4 - P5). This data relates to Table 2. (XLSX 516 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs expanded in pHPL between subsequent passages. Complete list of enriched GO terms for pHPL-ASCs between subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P1 - P2, P2 - P3, P3 - P4, P4 - P5). This data relates to Table 3. (XLSX 349 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs expanded in FBS between P0 and subsequent passages. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for FBS-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P0 - P2, P0 - P3, P0 - P4, P0 - P5). This data relates to Fig. 3a. (XLSX 166 kb)

Up- and downregulated gene list for ASCs expanded in pHPL between P0 and subsequent passages. Complete list of up- and downregulated genes for pHPL-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P0 - P2, P0 - P3, P0 - P4, P0 - P5). This data relates to Fig. 3b. (XLSX 206 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs expanded in FBS between P0 and subsequent passages. Complete list of enriched GO terms for FBS-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P0 - P2, P0 - P3, P0 - P4, P0 - P5). This data relates to Table 4. (XLSX 1145 kb)

Gene ontology terms for ASCs expanded in pHPL between P0 and subsequent passages. Complete list of enriched GO terms for pHPL-ASCs between P0 and subsequent passages (P0 - P1, P0 - P2, P0 - P3, P0 - P4, P0 - P5). This data relates to Table 5. (XLSX 1289 kb)

FBS and pHPL-ASC passage specific gene expression profile. A complete list of genes comprising the FBS and pHPL-ASC passage specific gene expression profile. (XLSX 89 kb)

FBS and pHPL-ASC medium supplementation specific gene expression profile. A complete list of genes comprising the FBS and pHPL-ASC medium supplementation specific gene expression profile. (XLSX 67 kb)