Abstract

Background

Targeted chronic disease programs are vital to improving health outcomes for Indigenous people globally. In Australia it is not known where evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been implemented. This scoping review geographically examines where evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal people have been implemented in the Australian primary health care setting. Secondary objectives include scoping programs for evidence of partnerships with Aboriginal organisations, and use of ethical protocols. By doing so, geographical gaps in the literature and variations in ethical approaches to conducting program evaluations are highlighted.

Methods

The objectives, inclusion criteria and methods for this scoping review were specified in advance and documented in a published protocol. This scoping review was undertaken in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scoping review methodology. The search included 11 academic databases, clinical trial registries, and the grey literature.

Results

The search resulted in 6894 citations, with 241 retrieved from the grey literature and targeted organisation websites. Title, abstract, and full-text screening was conducted by two independent reviewers, with 314 citations undergoing full review. Of these, 74 citations evaluating 50 programs met the inclusion criteria. Of the programs included in the geographical analysis (n = 40), 32.1% were implemented in Major Cities and 29.6% in Very Remote areas of Australia. A smaller proportion of programs were delivered in Inner Regional (12.3%), Outer Regional (18.5%) and Remote areas (7.4%) of Australia. Overall, 90% (n = 45) of the included programs collaborated with an Aboriginal organisation in the implementation and/or evaluation of the program. Variation in the use of ethical guidelines and protocols in the evaluation process was evident.

Conclusions

A greater focus on the evaluation of chronic disease programs for Aboriginal people residing in Inner and Outer Regional areas, and Remote areas of Australia is required. Across all geographical areas further efforts should be made to conduct evaluations in partnership with Aboriginal communities residing in the geographical region of program implementation. The need for more scientifically and ethically rigorous approaches to Aboriginal health program evaluations is evident.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12889-019-7463-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; Oceanic ancestry group; Chronic disease; Primary health care; Health services, indigenous; Program evaluation; Bioethics

Background

It is well established that Indigenous people experience poorer health outcomes than non-Indigenous people globally [1]. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, like other Indigenous populations in Canada, New Zealand and the United States, endure ongoing health inequities such as a high burden of chronic disease and difficulty accessing culturally safe health care [2, 3]. Chronic diseases with strong environmental and behavioural etiology, such as cardiovascular disease and Type Two Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM), contribute to approximately 80% of the mortality gap between Australian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people between 35 and 74 years of age [4]. Aboriginal people residing in more geographically remote areas experience further disadvantage and a higher burden of chronic disease [5]. For example, the proportion of Aboriginal people with Diabetes Mellitus in Very Remote areas of Australia is approximately twice that of Aboriginal people in Major Cities [6]. The lack of affordable fresh fruit and vegetables in these areas is one contributing factor [7].

Targeted chronic disease prevention and management programs delivered in the primary health care setting are imperative to alleviating the burden of disease and improving health outcomes for Indigenous people [3, 8]. In Australia, little progress has been made in improving health outcomes, the distribution of chronic disease, and risk factors for developing disease for Aboriginal people [2, 9]. This is despite numerous funded Aboriginal chronic disease programs implemented at a national level (e.g., Aboriginal Chronic Disease Package, 2008) and initiatives under the ‘Closing the Gap’ policy [2, 9]. The ineffectiveness of health programs has been attributed to multiple factors, including short government funding cycles, a lack of community ownership and consultation, and a ‘one size fits all’ approach to program design and implementation [10, 11]. Furthermore, only a small proportion of Aboriginal health programs have been evaluated (8%), with only 6% of program evaluations applying rigorous evaluation methodologies to measure program effectiveness [12, 13]. The paucity of Aboriginal health program evaluations has resulted in little opportunity to improve or modify existing programs in response to program outcomes, contributing to the cycle of program ineffectiveness.

The need for Aboriginal community-driven programs and governance of primary health care services, as supported by the international right to self-determination for Indigenous people, is becoming increasingly recognised as a key strategy to alleviating the burden of chronic disease [14–16]. Strong evidence supports the role of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) and other Aboriginal organisations in improving the accessibility, appropriateness and effectiveness of primary health care services through the provision of culturally appropriate care which respects the cultural values and beliefs of Aboriginal people [8]. Therefore, the involvement of ACCHOs and other Aboriginal organisations in the design and implementation of chronic disease programs is imperative [15, 17–19]. Moreover, a community-based approach to program design, implementation, evaluation, sustainability and transferability acknowledges the diversity of Aboriginal culture, language and customs [10]. This ensures that chronic disease programs are tailored to local needs and evaluated in partnership with community, recognises the strengths and resilience of Aboriginal people, and empowers Aboriginal communities to promote their own health and wellbeing [20].

Although there has been a rhetorical shift from government initiated health programs to community-developed health programs for Aboriginal people in Australia [21], it is not known whether the distribution of chronic disease programs has been proportionate to the population distribution of Aboriginal people, or to the burden of chronic disease. Furthermore, it is not known geographically where evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal people in the primary health care setting have been implemented. Therefore, the purpose of this scoping review was to identify where evaluated chronic disease programs have been implemented in the primary health care setting [22]. Specifically, this review sought to determine whether this distribution was proportionate to the Aboriginal population distribution, and burden of disease across all geographical areas of Australia and by doing so, highlight geographical gaps in the literature to identify priority areas for the implementation of chronic disease programs. Secondary objectives included scoping for evidence of partnerships with ACCHOs and other Aboriginal organisations, in addition to the use of ethical guidelines or protocols in the reporting of programs.

Methods

This study provides a systematic scoping review geographically examining the distribution of evaluated chronic disease prevention and management programs implemented for Australian Aboriginal people in the primary health care setting which includes community-health settings, general practice clinics and ACCHOs [22]. This review was undertaken in accordance with the methodology for conducting scoping reviews as outlined in the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2017: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews [23]. Search terms were designed in a PCC (Population, Concept, Context) format by the research team and in collaboration with a health librarian. The premise and methods for this review have been published elsewhere in greater detail [22]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were adhered to in the reporting of this review (Additional file 1).

Search strategy

A preliminary search was conducted in MEDLINE and CINAHL using keywords to develop a tailored search strategy for each information source. A combination of Boolean operators, truncations and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used to develop database search strategies (Additional file 2). The following databases were searched: Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Scopus, Embase (Elsevier), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ISI Web of Science, SocINDEX (EBSCO-host), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), PubMed Central and PsycINFO (OVID).

Keywords were used to search the following information sources for unpublished studies, grey literature, and trials in order to avoid publication bias: Lowitja Institute, Indigenous Healthinfonet, National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), Department of Health (Australian Government), informIT, Google, Cochrane Central Trials Register of Controlled Trials, ANZ Clinical Trials Registry, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO International Clinical trial Registry Platform (ICTRP), Primary Health Care Research and Information Service (PHCRIS), ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, Trove and OAIster.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

This review considered literature based on the following criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

Involved Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander adults 18 years of age and above who had participated in a chronic disease program Program evaluation involved over 50% Aboriginal participation or stratified analysis for Aboriginal people |

Involved children or young people less than 18 years of age |

| Concept | Evaluated chronic disease programs involving disease prevention and/or management activities for, but not limited to, chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, asthma, arthritis, chronic pain, cancer, mental health conditions, chronic kidney disease, liver disease or tooth decay and/or risk factors for developing chronic diseases, such as an unhealthy weight, exceeding alcohol drinking guidelines, smoking, poor diet or physical inactivity. | Program not evaluated |

| Context | Program evaluated in the Australian primary health care context (e.g. ACCHOs, general practice clinics and community-health clinics) |

Programs evaluated in inpatient hospital facilities and sub-acute rehabilitation facilities Outcomes not published in English |

No restrictions were placed on the quality of evaluation or study design. As stated in the scoping review protocol, programs evaluated by any party to any level were included [22]. Literature published from 1 January 2006, was included in order to capture programs published since the launch of the ‘Closing the Gap’ campaign, which resulted in a greater focus on addressing health inequities experienced by Aboriginal people in Australia [9].

For consistency, the term ‘Aboriginal’ has been used throughout this review to refer to both Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. This is due to brevity, and no disrespect is intended to any individual or group. The term ‘Indigenous’ has been reserved for the global context.

Study selection and data extraction

Searches for published and unpublished literature were conducted by a health librarian. Titles and abstracts retrieved from the search were screened independently by two reviewers (HB and MJB). Conflicts were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (CK). Full text review and data extraction was then conducted independently by two reviewers (HB and MJB) on selected articles. Reasons for exclusion were provided for articles that did not meet the review criteria. The reference lists of citations requiring full text review were also screened for additional citations in order to ensure that all possible literature was included.

Extracted data were categorised under the following headings: author, year of publication, year of program implementation, location of program implementation/evaluation, evaluation methods, involvement of an ACCHO/other Aboriginal organisation and reference to Australian National Health and Medical Research Council’s (NHMRC) ‘Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research’ guideline, and other ethical protocols [24, 25]. Geographical coordinates were then assigned to included programs based on the extracted data. Where specific implementation sites were not stated, the approximate location(s) were geocoded and coordinates extracted. If this information was unavailable, the corresponding author was contacted. If studies did not specify where the program was evaluated, the institution listed for the first author was used as a proxy for place of evaluation. This assumed that first authorship implied a lead role in the evaluation.

Coordinates were then exported to ArcGIS® ArcMap™ and overlayed with the Remoteness Areas of Australia for analysis [26]. To define remoteness, the Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) was applied, which is a categorisation of the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+) [27]. Areas are classified as: i) Major Cities of Australia, ii) Inner Regional Australia, iii) Outer Regional Australia, iv) Remote Australia, and v) Very Remote Australia. Euclidean distance between the implementation site and evaluation were also extracted in ArcGIS® ArcMap™ [26]. Summary statistics were produced to examine the distance between implementation site(s) and place of evaluation. Locations of implementation and evaluation were stratified by Remoteness Area and cross-tabulated.

The extracted data, synthesis of findings and review outcomes, were critically reviewed for culturally appropriateness by two Aboriginal researchers, as stated in the review protocol [22].

Results

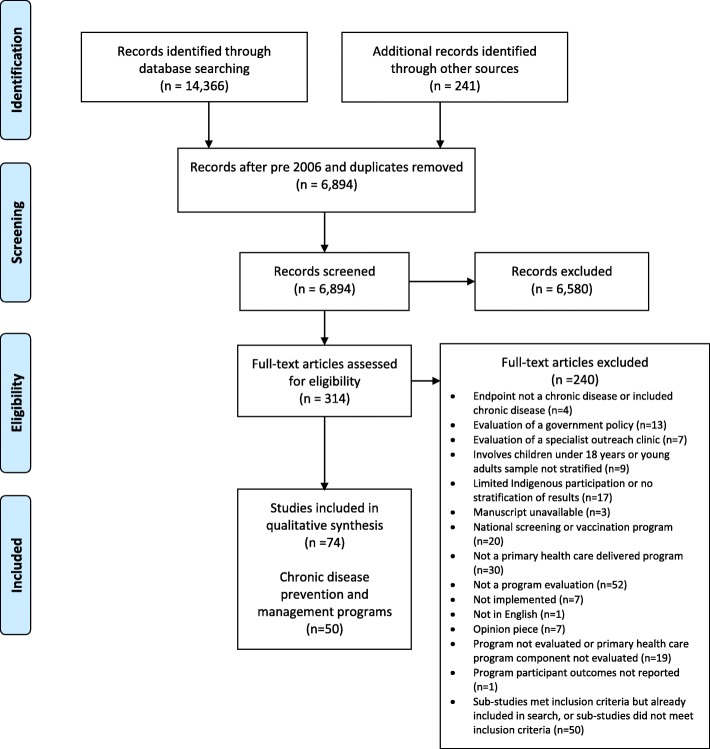

Database searches yielded 14,366 citations. An additional 241 citations were retrieved from a search of the grey literature and targeted organisation websites. A total of 6894 title and abstracts were screened, with duplicates removed. The full texts of 314 citations were screened for relevance to the review criteria, identifying 74 pertinent records evaluating 50 chronic disease prevention and management programs (Fig. 1 – PRISMA Flow Diagram). One of these records included reference to three evaluated programs [28].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of the systematic review process for this review

Reasons for excluding records were provided (Additional file 3). The most frequent reason provided for exclusion was that the record was ‘not a program evaluation’ (n = 52), followed by ‘Sub-studies met inclusion criteria but already included in search, or sub-studies did not meet inclusion criteria’ (n = 50) and ‘not a primary health care delivered program’ (n = 30). Excluded records included 20 records which focused on evaluating national screening and vaccination programs. These were excluded as findings were based on national or state-wide aggregate data which would have been difficult to include in the geographical analysis.

Finding 1: heterogeneity of included programs

Citations meeting the review criteria (n = 74) included evaluated programs (n = 50) that addressed multiple chronic diseases (n = 16), a specific chronic disease (cardiovascular disease n = 5, diabetes mellitus n = 6, chronic kidney disease n = 3, liver disease n = 2, mental illness n = 4, oral disease n = 2 and polycystic ovarian syndrome n = 1) or risk factors for developing chronic disease (drug and alcohol misuse n = 2, poor nutrition and physical inactivity n = 3 and smoking n = 6) (Table 2). Of the included programs, 74% (n = 37) aimed to prevent and/or manage chronic disease using disease-specific screening, early intervention or treatment strategies, with the remaining programs (n = 13) applying general health promotion approaches to disease prevention, such as empowering participants to implement activities to improve their health.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included program evaluations

| Program name | Citation | Years of program | Type of program | Targeted chronic disease(s)/risk factor(s) | Evaluation study design | Aboriginal participant sample size | Evaluation outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking Classes for Diabetes Program |

Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council 2009 [28] Abbott, Davison, Moore & Rubinstein 2010 [29] Abbott, Davison, Moore & Rubinstein 2012 [30] |

2002–2007 | Health promotion | Diabetes, Poor nutrition | Qualitative - post program semi-structured interviews | 73 program participants, 23 interview participants (4 m, 19 f) | Participant experience |

| Health Lifestyle and Weight Management Program | Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council 2009 [28] | 2005–2008 | Health promotion and chronic disease prevention | Poor nutrition, physical inactivity | Mixed methods -pre, interim and post program quantitative and qualitative measures | Not reported |

Clinical measures: BMI, height, weight, blood pressure, blood sugar level, waist, chest and hip ratio Participant experience |

| Healthy Food Awareness Program | Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council 2009 [28] | 2008 | Chronic disease prevention and management | Poor nutrition, physical inactivity, smoking, obesity, renal disease, diabetes and other chronic diseases | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| ‘No More Dhonga’ Short Course | Adams et al. 2006 [31] | 2004 | Health promotion and chronic disease prevention | Smoking | Mixed methods-interim and post program measures | 32 participants |

Stakeholder feedback Course attendance and smoking quit rate |

| Home-Based, Outreach case Management of chronic disease Exploratory (HOME) Study program | Askew et al. 2016 [32] | Not reported | Chronic disease management | Diabetes type 2, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, kidney disease | Mixed methods-post program semi-structured interviews, pre, interim and post program quantitative measures | 41 participants, data collected from 37 participants (32 m, 68% f) | Feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness of model |

| Renal Treatment Program | Bailie et al. 2006 [33] | 1995–1999 | Chronic disease management | End state renal disease | Quantitative-interrupted time series of pre/post quantitative measures | 266 participants, data collected from 98 participants | Clinical measure: blood pressure |

| Moorditj Djena program | Ballestas et al. 2014 [34] | 2011-ongoing | Chronic disease management | Diabetes type 2, peripheral arterial disease, peripheral neuropathy | Mixed methods- interim program focus groups, interviews and review of quantitative data |

Data collected from 702 participants (majority Aboriginal – not specified) Participation not reported for qualitative data |

Program delivery, quality of implementation and organizational context |

| Nurse-led practitioner project for chronic kidney disease | Barrett et al. 2015 [35] | 2012-ongoing | Chronic disease management | Chronic kidney disease | Quantitative-clinical audit | 187 participants | Rates of detection and improvement in chronic disease management |

| Flinders self-management model (CCSM) | Battersby et al. 2008 [36] | 2001–2002 | Chronic disease management | Diabetes | Mixed methods-pilot study with pre, interim and post quantitative data, post program focus group | 60 participants (28 m, 32 f) | Program acceptability and clinical outcomes (HbA1c, Diabetes Assessment Form, SF-12) |

| Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome clinic program | Boyle et al. 2017 [37] | 2012–2013 | Chronic disease management | Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) | Mixed methods-post implementation evaluation using clinical audit, semi-structured interviews and focus groups | Clinical audit involved 36 f participants, interviews with 8 clinicians and focus group with 8 f participants | Process evaluation of program fidelity, barriers and enablers and whether the program met community needs |

| Diabetic retinopathy screening program | Brazionis et al. 2018 [38] | 2014–2016 | Chronic disease prevention and management | Diabetes | Quantitative- cross-sectional study design | 301 participants (33% m, 67% f) | Clinical effectiveness: diabetic retinopathy prevalence rates and severity compared to other screening programs |

| Primary Health Care Outreach program of Aboriginal Health Checks | Burgess et al. 2011 [39] | 2005 | Chronic disease management | Cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases | Quantitative- interrupted time series study with pre/post measures | 64 participants (43 m, 21 f) | Clinical measures (absolute cardiovascular risk, blood pressure, BMI), follow up appointments and outcomes |

| 12 week exercise and nutrition program |

Canuto et al. 2012 [40] Canuto 2013 [41] Canuto et al. 2013 [42] |

2010–2011 | Health promotion | Poor nutrition, physical inactivity | Mixed methods-pragmatic randomised trial with mixed methods process evaluation | 100 f participants at baseline, 41 lost to follow up. Not reported how many participated in interviews |

Program effectiveness on waist circumference, weigh and biomedical metabolic markers Factors influencing program attendance |

| Healthy Lifestyle Programme (HELP) | Chan et al. 2007 [43] | Not reported | Chronic disease management | Diabetes, cardiovascular risk factors | Quantitative- pre and post study | 101 participants | Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention on clinical measures |

| Cardiac failure education program |

Clark et al. 2014 [44] Clark et al. 2015 [45] |

Not reported | Chronic disease management | Cardiovascular disease | Mixed methods-pilot study with pre and post data | 5 participants (3 m, 2 f) | Feasibility and acceptability of resource |

| Drug and alcohol screening intervention | Clifford et al. 2013 [46] | Not reported | Chronic disease prevention | Drug and alcohol misuse | Quantitative- pre and post study | 314 participants | Proportion of clients with alcohol screening |

| Health literacy intervention | Crengle et al. 2017 [47] | 2013 | Chronic disease management | Cardiovascular disease | Quantitative-multi-site pre and post study | 171 participants, 11 lost to follow up | Effect of intervention on medication knowledge |

| Grog mob | D’Abbs et al. 2013 [48] | 2008–2009 | Chronic disease prevention | Risky alcohol behaviour | Mixed methods-descriptive analysis of post program data | 49 participants | Examine whether program met its objectives, document implementation processes and gauge the impact on client outcomes |

| Cardiac and pulmonary secondary prevention program | Davey et al. 2014 [49] | 2011–2013 | Chronic disease prevention and management | Cardiovascular and pulmonary disease | Mixed methods-pre and post study | 92 participants (36 m, 56 f), qualitative feedback from 51 participants | Program uptake and effectiveness |

| Smoking cessation program | DiGiacomo et al. 2007 [50] | 2005–2006 | Chronic disease prevention | Smoking | Quantitative- case review | 37 participants (10 m, 27 f) | Screening rates and quit attempts |

| ‘Heart health’ program cardiac secondary prevention |

Dimer et al. 2010 [51] Dimer et al. 2012 [52] Dimer et al. 2013 [53] Maiorana et al. 2012 [54] Maiorana et al. 2015 [55] |

2009–2010 | Chronic disease prevention and management | Cardiovascular disease | Mixed methods-pre and post data, interviews, yarning sessions and questionnaires | 98 participants (35 m, 63 f) | Uptake and effectiveness of program on lifestyle and cardiovascular risk factors |

| Intensive quit smoking intervention | Eades et al. 2012 [56] | 2005–2009 | Health promotion and chronic disease prevention | Smoking | Quantitative-randomised controlled trial | 263 f participants | Effectiveness of intervention on smoking rates |

| Give up the smokes program | Gould, McGechan & Zwan 2010 [57] | 2007–2008 | Health promotion and chronic disease prevention | Smoking | Quantitative- pre and post study | 10 participants | Cultural appropriateness of program |

| Diabetes Management and Care program | Gracey et al. 2006 [58] | 2002 | Chronic disease prevention and management | Diabetes, poor nutrition, physical inactivity | Quantitative- pre and post study | 418 participants (181 m, 237 f) | Impact of program on clinical measures |

| Koorie Men’s health day | Isaacs & Lampitt 2014 [59] | Not reported | Health promotion and chronic disease prevention | Mental illness | Mixed methods-descriptive study | 20 m participants (data available for 17) | Model outcomes |

| Oral health literacy program | Ju et al. 2017 [60] | Not reported | Health promotion | Oral health | Quantitative-randomised controlled trial | 400 participants at baseline, 106 lost to follow up | Oral health literacy |

| Oral health periodontal program |

Kapellas et al. 2013 [61] Kapellas et al. 2014a [62] Kapellas et al. 2014b [63] Kapellas et al. 2017 [64] |

2010–2012 | Chronic disease prevention and management | Oral health | Quantitative-randomised controlled trial | 273 participants, follow up data available for 169 | Improvements in clinical outcomes |

| Structured chronic disease care planning program | Kowanko et al. 2012 [65] | 2008–2011 | Chronic disease management | All chronic diseases | Mixed methods-Participatory Action Research framework | 36 participants involved in longitudinal study, otherwise not reported | Impact of chronic disease self-management strategies on health outcomes |

| Nurse-led Chronic Kidney Disease program | Lawton et al. 2016 [66] | 2007-ongoing | Chronic disease management | Chronic kidney disease | Quantitative-interrupted time series | Not reported | Improvement in rate of chronic kidney disease detection and clinical markers |

| Walk about Together Program (WAT) | Longstreet et al. 2008 [67] | 2003–2005 | Health promotion | Unhealthy weight, poor nutrition | Quantitative-pre and post study | 100 participants (12% m, 88% f). | Nutrient intake of program participants |

| Be Our Ally Beat Smoking (BOABS) program |

Marley et al. 2014a [68] Marley et al. 2014b [18] |

2009–2012 | Health promotion | Smoking | Mixed methods-randomised controlled trial with qualitative component | 168 randomised, 19 lost to follow up | Efficacy of smoking cessation program at 12 months follow up |

| Getting better at chronic care program |

McDermott et al. 2015 [69] Schmidt, Campbell & McDermott 2016 [70] Segal et al. 2016 [71] |

2011–2013 | Chronic disease management | Diabetes and other chronic diseases | Mixed methods-pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial with qualitative component and economic analysis | 213 participants randomised (38% m, 62% female), 24 lost to follow up, 21 interview participants |

Program effectiveness in improving care of participants with diabetes Experience of health workers implementing program Program cost-effectiveness |

| Work it out program | Mills et al. 2017 [72] | 2012–2014 | Chronic disease prevention and management | Cardiovascular disease | Quantitative- quasi-experimental with pre and post data | 85 participants | Impact on clinical outcomes at 12 weeks post implementation |

| Mental illness brief intervention program |

Nagel & Thompson 2008 [73] Nagel et al. 2008 [74] |

2004–2007 | Chronic disease management | Mental illness | Mixed methods-randomised controlled trial with qualitative component | 49 participants | Program effectiveness on clinical outcomes |

| Get Healthy Service program | Quinn et al. 2017 [75] | 2009–2015 | Health promotion | All chronic diseases | Mixed methods-pre and post study with qualitative component | 30 participants interviewed (5 m, 25 f), quantitative data collection involved 1462 participants | Program reach and impact on lifestyle risk factors |

| Antiviral therapy Hepatitis C program | Read et al. 2017 [76] | 2016-ongoing | Chronic disease prevention and management | Hepatitis C | Quantitative-observational cohort study | 23 participants | Efficacy of program |

| Quality Assurance for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Medical Services (QAAMS) program |

Shephard 2006 [77] Shephard et al. 2017 [78] Spaeth, Shephard & Schatz 2014 [79] |

1999-ongoing | Chronic disease management | Diabetes | Mixed methods-key stakeholder and client questionnaire with open questions, case studies, comparison of baseline and post implementation data, longitudinal quality assurance data, before and after study design |

161 participants completed client questionnaire, 907 program participants |

Program satisfaction Quality assurance and imprecision Clinical and operational efficiency |

| Point-of-Care in Aboriginal Hands | Shepherd et al. 2006 [80] | 2001-ongoing | Chronic disease management | All chronic diseases | Mixed methods-interviews, comparison of baseline and post implementation data | Data collected from 626 participants | Community acceptability of program |

| Western Desert Kidney Health Screening program | Sinclair et al. 2016 [81] | 2012 | Chronic disease prevention and management | Chronic kidney disease, diabetes | Qualitative-interviews | 26 participants (11 m, 15 f) | Community acceptability of program |

| COACH programme | Ski et al. 2017 [82] | Not reported | Chronic disease prevention and management | Cardiovascular disease | Quantitative-longitudinal outcomes in participants | Not reported | Program effectiveness in reducing cardiovascular risk |

| Diabetic retinopathy screening program | Spurling et al. 2010 [83] | 2007–2009 | Chronic disease management | Diabetes | Mixed methods-semi-structured interviews, descriptive analysis of demographic data and screening rates | 132 participants (60 m, 72 f) | Program impact and accessibility |

| Indigenous adult health checks program | Spurling, Hayman & Cooney 2009 [84] | 2007–2008 | Chronic disease prevention and management | All chronic diseases | Quantitative- cross-sectional study | 413 participants | Evaluate role of program |

| Shared medical appointment program | Stevens et al. 2016 [85] | Not reported | Chronic disease prevention and management | All chronic diseases | Mixed methods-post program questionnaires, interviews and field notes | 14 m participants | Program acceptability and appropriateness |

| Community singing program |

Sun & Buys 2012 [86] Sun & Buys 2013a [87] Sun & Buys 2013b [88] Sun & Buys 2013c [89] Sun & Buys 2013d [90] Sun & Buys 2013e [91] Sun & Buys 2013f [92] Sun & Buys 2016 [93] |

2010–2012 | Chronic disease management | Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, depression, psychosis | Mixed methods-pre and post study design with numerous outcome measures, questionnaires, focus group sessions | 45 participants | Program effectiveness and impact |

| Home Medicines Review program |

Swain 2016 [94] Swain & Barclay 2015 [95] |

2001-ongoing | Chronic disease management | All chronic diseases | Mixed methods-focus group sessions with indigenous consumers, interviews with health workers, cross-sectional survey with pharmacists | 102 participants |

Usefulness of program for Indigenous people Facilitators and barriers to program uptake |

| ‘Yaka Narali’ Tackling Indigenous Smoking program | Tane et al. 2016 [96] | 2009-ongoing | Health promotion | Smoking | Qualitative-interviews | 30 participants | Program effectiveness |

| Ngangkari Program | Togni 2017 [97] | Not reported | Chronic disease management | Mental illness, Social and Emotional Wellbeing | Qualitative-interviews and focus group sessions | 18 participants | Developmental evaluation of program model |

| Deadly Liver Mob program | Treloar et al. 2018 [98] | 2013-ongoing | Health promotion and chronic disease prevention | Hepatitis C | Mixed methods-pre and post study with qualitative component | Quantitative data collected from 710 participants, 19 participant interviews | Program acceptability |

| Music therapy program | Truasheim 2014 [99] | 2012 | Chronic disease management | All chronic diseases | Mixed methods-survey data and some clinical measures | 13 participants (4 m, 9 f) | Examine cultural safety of program |

| Perinatal mental health program | Verrier et al. 2013 [100] | Not reported | Chronic disease prevention and management | Mental illness, Social and Emotional Wellbeing | Mixed methods-pre and post study with quantitative and qualitative data | Not reported | Program impact |

The data collection methods of program evaluations varied, with over half of the program evaluations using a mixed methods approach (n = 26, 52%), followed by a quantitative only (n = 19, 38%) or qualitative only (n = 4, 8%) approach. The methods of evaluation were not reported for one program [28], however, a summary of outcomes were provided; hence the program was included in the review. Of the included programs, only seven were evaluated using a randomised controlled trial (RCT) study design, with only one study (an RCT) including an economic evaluation of program cost-effectiveness.

Finding 2: geographical distribution of programs

Four of the included programs were excluded from the geographical analysis as programs were implemented state-wide or nationally (Home Medicines Review Program [94, 95], Get Healthy Service Program [75], QAAMS Program [77–79] and COACH Program [82]). Five of the included programs were also excluded from the geographical analysis as authors did not respond to the request for additional information. Geographical coordinates for program implementation sites were available for 41 of the included programs (82% of all included programs). However, one program was omitted from the analyses as the evaluation was undertaken outside of Australia as part of a multi-site program evaluation [47]. A total of 81 implementation sites for the 40 programs (80% of all included programs) with available locations were geo-coded and geographically analysed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Geographical location of included programsa

| Evaluation n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation n (%) | Major Cities | Inner Regional | Outer Regional | Remote | Very Remote | Total | Aboriginal population (%)b |

| Major Cities | 26 (32.1) | 26 (32.1) | 37.4 | ||||

| Inner Regional | 10 (12.3) | 10 (12.3) | 23.7 | ||||

| Outer Regional | 14 (17.3) | 1 (1.2) | 15 (18.5) | 20.3 | |||

| Remote | 3 (3.7) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | 6 (7.4) | 6.7 | ||

| Very Remote | 15 (18.5) | 6 (7.4) | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | 24 (29.6) | 11.9 | |

| Total | 58 (71.6) | 10 (12.3) | 8 (9.9) | 4 (4.9) | 1 (1.2) | 81 (100) | 100 |

aExcludes included programs implemented at a national or state level (Home Medicines Review Program [94, 95], Get Healthy Service Program [75], QAAMS Program [77–79] and COACH Program [82]), programs where geographical coordinates were not provided by authors (n = 5) and one program where the evaluation was undertaken overseas as part of a multi-site program evaluation [47]

b2016 Australian Aboriginal population distribution across Remoteness Areas [101]

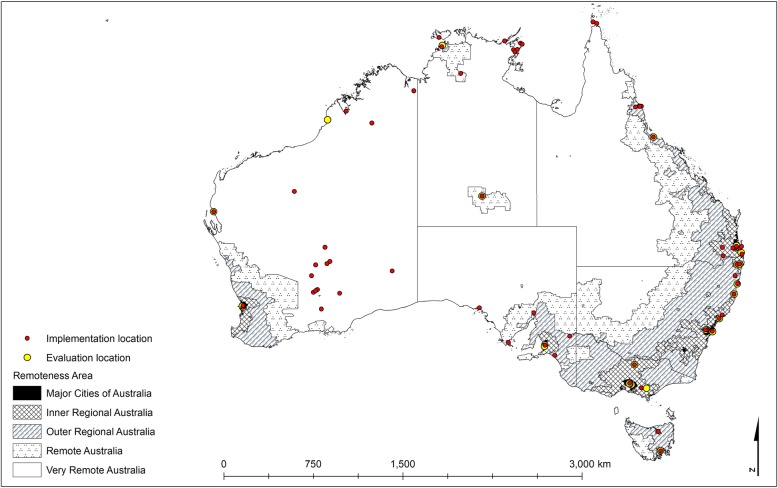

Of the included programs in the geographical analysis (n = 40), 32.1% were implemented for Aboriginal people residing in Major Cities of Australia and 29.6% for Aboriginal people residing in Very Remote Australia. The remaining programs were implemented for Aboriginal people residing in the intermediate remoteness areas of Inner Regional Australia, Outer Regional Australia, and Remote Australia (12.3, 18.5 and 7.4% respectively).

The location of program evaluation was reported for 25 of the programs included in the geographical analysis. First author affiliation was used as a proxy for the location of program evaluation for the remaining 15 programs. Evaluation activity was predominately undertaken in Major Cities of Australia (71.6%), with the remaining studies declining in order of remoteness. Of the identifiable implementation locations (n = 81), 18 (22%) of these also had an evaluation undertaken on site. For studies with the site(s) of implementation and evaluation available, the mean distance between implementation and evaluation was 660 km (95% CI 470–850; maximum 3041; median 223). A visual representation of the distribution of included programs is provided (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Locations of the implementation and evaluation of programs in relation to the Remoteness Areas of Australia [27]

The sample size of programs retrieved for highly prevalent chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and T2DM, was deemed insufficient to geographically analyse whether the distribution of evaluated programs were proportionate to the burden of chronic disease across all Remoteness areas.

Finding 3: ethical approaches to program evaluation

Of the 50 programs included in the review, 39 (78%) reported on the involvement of an ACCHO in the implementation or evaluation process (Additional file 4). Of the included programs that did not report on the involvement of an ACCHO, six of these referred to the involvement of another Aboriginal organisation (12%). Overall, 90% (n = 45) of the included programs collaborated with an Aboriginal organisation in the implementation and/or evaluation of the program.

When examining the affiliation of the first author of the included citations (n = 74), 74% (n = 55) were associated with a university or research institution, 9.5% (n = 7) with an ACCHO or other Aboriginal organisation, 9.5% (n = 7) with a non-Aboriginal health service or Non-Government Organisation (NGO) and 7% (n = 5) with both a university or research institution and an ACCHO.

Of the 74 citations retrieved, seven explicitly referred to the NHMRC’s ‘Values and Ethics: Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research’ as a guideline underpinning the evaluation design and conduct [24]. However, 70% of citations (n = 52), particularly those published in a peer-reviewed journal, included a formal statement of ethical review and approval by a Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) affiliated with a research institution or university. Only 23 citations (31%) discussed the use of other ethical protocols or a community-based ethical review process. These citations varied broadly in their descriptions of adhering to local cultural guidelines or consulting with an appointed Aboriginal advisory group. For example, Askew et al. (2016) [32] described the formation of a research advisory group consisting of both Aboriginal community members and experienced researchers who provided research governance and oversight, whereas Treloar et al. (2018) [98] described consulting with an Aboriginal advisory group in the program development phase rather than the evaluation process. Consideration of cultural sensitivities was also discussed broadly in some papers, including processes undertaken to build rapport with collaborating Aboriginal communities prior to the conduct of an evaluation [59, 72] and the receipt of cultural guidance or support from a steering group of Aboriginal people or Elders [40, 83].

Discussion

This review highlights the paucity of Aboriginal chronic disease program evaluations conducted in the primary health care setting across all geographical regions of Australia. Previous studies have acknowledged that only a small proportion of Aboriginal health programs have been subject to an evaluation process [12, 13]. Therefore, the included programs in this review are not representative of all chronic disease programs implemented for Aboriginal people across Australia. Of those included, the majority targeted highly prevalent chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and T2DM, or risk factors for developing chronic disease, such as smoking and physical inactivity [2]. Due to the heterogeneity of programs across all geographical regions and small sample size, the review was unable to ascertain whether the spread of programs was proportionate to the distribution of chronic disease across all Remoteness Areas of Australia. For example, it was difficult to conclude whether a greater focus on the management of T2DM for Aboriginal people residing in Very Remote areas is required, where the prevalence of T2DM is approximately twice of Aboriginal people residing in Major Cities [6]. However, the small proportion of evaluated social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) programs (e.g., mental health programs) was noted across all geographical regions, supporting the need for tailored early intervention and screening SEWB programs for Aboriginal people [19]. Internationally, tailored programs for mental health prevention have been deemed particularly important for Indigenous people, particularly those including an exploration of cultural identity [102, 103].

Overall, Major Cities and Very Remote areas of Australia displayed similar levels of chronic disease program implementation activity, with less activity noted for Inner and Outer Regional (IOR) areas and Remote areas of Australia. A greater focus on chronic disease programs for Very Remote Aboriginal people when compared to IOR or Remote Aboriginal people could be informed by national data which indicates that the burden of chronic disease in Aboriginal people increases with Remoteness [6]. However, less Aboriginal people reside in Very Remote areas when compared to IOR areas (11.9% compared to 23.7 and 20.3% respectively), suggesting there is a need for the evaluation of chronic disease programs for Aboriginal people residing in IOR areas [101]. Across all geographical areas in Australia, it is anticipated that the demand for chronic disease prevention programs will increase over time, due to a higher Aboriginal population growth rate when compared to non-Aboriginal populations as indicated by 2017 national data (2.26 babies per Aboriginal woman compared to 1.75 babies per non-Aboriginal woman) [104, 105]. The demand for chronic disease programs may also increase for Indigenous people in other countries (e.g., Canada) experiencing similar population growth (2.2 babies per Aboriginal woman compared to 1.6 babies per non-Aboriginal woman in Canada) [106].

When considering evaluation activity, higher levels of evaluation were noted for Major Cities (71.6%) when compared to Very Remote areas (1.2%). This is despite the fact that national data indicates that less Aboriginal people reside in Major Cities compared to the total Australian population (37% compared to 73% respectively) [101]. Further to this, the proportion of Aboriginal people is higher in all other Remoteness Areas of Australia, relative to the total Australian population [101]. This finding suggests there is a need for more Aboriginal community-led research as supported by the broader literature [15, 19, 20]. However, caution should be applied in interpreting these findings as first author affiliation was used as a proxy for the location of program evaluation for 15 of the 40 programs included in the geographical analysis. The rationale for this assumption was that first authorship implied a lead role in the evaluation.

When examining first author affiliation for all included citations (n = 74), 74% (n = 55) of citations were associated with a university or research institution, with only 9.5% (n = 7) citations associated with an ACCHO or other Aboriginal organisation. A previous review of Aboriginal health programs in Australia also found that the majority of program evaluations (72%) were led by a research institution or university rather than an Aboriginal community organisation [107]. However, first author affiliation with a research institution or university does not necessarily mean that the evaluation did not have significant Aboriginal community input; particularly as 90% (n = 45) of included programs provided details of collaborating with an ACCHO or other Aboriginal organisation in the development or evaluation of the program. Strong support for the appropriateness of ACCHOs as a collaborating organisation for activities involving Aboriginal people is found in the literature [108]. Generally, ACCHOs are geographically accessible to Aboriginal people and valued for the provision of culturally safe primary health care [8, 109, 110].

Although the majority of programs partnered with an ACCHO or Aboriginal organisation, it is difficult to ascertain for all programs, the degree of community ownership and involvement in the evaluation process. This includes steps taken by evaluators to ensure the evaluation process was ethically and culturally appropriate for Aboriginal people [20]. As reporting the formal ethical review of a research project is a standard requirement for publication in a peer-reviewed journal, both nationally and internationally, it is not surprising that the majority of citations (70%, n = 52) provided a statement of formal review by an appointed committee (e.g. HREC). However, only 31% of the included citations (n = 23) provided some evidence of actions taken to adhere to Aboriginal community-based ethical protocols, or engagement with an Aboriginal advisory group in the design of the program or conduct of the evaluation. Indeed, a statement of formal ethical review does not provide sufficient detail describing how Aboriginal people were consulted and included in the evaluation process. Other Aboriginal program evaluation frameworks and models of Aboriginal health research should also be consulted, which are valuable in informing approaches to conducting program evaluations in partnership with Aboriginal people [20, 25, 111, 112]. Program evaluations of Aboriginal programs excluding partnerships, often lack relevance and integrity, and fail to translate to outcomes for Aboriginal people [12, 113].

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this review. The selection criteria of the review influenced the geographical spread of studies retrieved. National screening and vaccination programs were excluded as program evaluations used national aggregate data. Geographical findings may also have been impacted by the exclusion of other programs which met the review criteria, but were excluded from the geographical analysis due to state-wide or national program implementation (Home Medicines Review Program [94, 95], Get Healthy Service Program [75], QAAMS Program [77–79] and COACH Program [82]). Furthermore, authors of five programs did not respond with additional information regarding the geographical program implementation locations which may also have influenced the analysis.

It is not known what proportion of evaluated chronic disease programs or implemented chronic disease programs have been included; a limitation cited by a similar review [107]. It is also possible that evaluated programs targeting more distal risk factors for chronic disease may have been overlooked. The availability of evaluation reports may also have influenced the types of citations retrieved. A recent investigation into the evaluation of health programs implemented for Aboriginal people in Australia found that only 33% of evaluation reports were available [20]. Further to this, it is acknowledged that a substantial amount of literature pertaining to Australian Aboriginal people is published in the grey literature [114]. Although the authors have made every effort to conduct a thorough search of the grey literature, it is possible some evaluation reports may not have been captured in this scoping review.

Recommendations

A greater focus is required on evaluating chronic disease prevention and management programs for Aboriginal people across all geographical areas, particularly for Aboriginal people residing in Inner and Outer Regional areas of Australia. In addition, there is a need to focus on evaluating Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB) programs developed for Aboriginal people. Programs should be implemented and evaluated in collaboration with partnering ACCHOs or other Aboriginal organisations, with an emphasis on accountability, sustainability, capacity-building, ownership and Aboriginal strengths. This includes equipping Aboriginal organizations with skills in conducting program evaluations. Evaluation reporting should be transparent in describing ethical approaches to conducting the program evaluation in partnership with Aboriginal communities. Furthermore, an evaluation process should be integrated into the design of Aboriginal health programs. Evaluation outcomes should be publicly available, ideally through the peer-reviewed literature, in order to build the evidence around the effectiveness of chronic disease programs for Indigenous peoples globally.

Conclusions

A greater focus on the implementation and evaluation of chronic disease prevention and management programs for Aboriginal people in Australia is required, particularly for Aboriginal people residing in Inner and Outer Regional Areas of Australia. There is also a need to conduct evaluations of Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB) programs across all geographical regions. This review highlights the need for more ethically rigorous approaches to Aboriginal health program evaluations which engage Aboriginal people in all stages of program design, implementation, evaluation and sustainability.

Additional files

PRISMA 2009 Checklist. This file contains the PRISMA checklist and co-relating page numbers to the items for reporting. (DOCX 25 kb)

Electronic search results and terms. This file contains a table of search results and terms used to retrieve studies from databases (DOCX 43 kb)

Excluded Studies. This file contains a table of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion. (DOCX 68 kb)

Data extraction: evidence of partnerships and reference to ethical guidelines. This file contains a table of data extracted in relation to the secondary objectives of this review; scoping evidence of partnerships with Indigenous organizations and ethical approaches to undertaking a program evaluation. (DOCX 95 kb)

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Nikki May for developing, testing and running the search strategies for the databases and undertaking a search for unpublished studies. We also acknowledge the support from librarians, Dorothy Rooney and Fiona Russell. We wish to thank Jason Kanoa and John Bell for contributing to the conception of this review in their capacities as CEO of Gunditjmara Aboriginal Cooperative (Warrnambool, Victoria) and CEO of Dhauwurd-Wurrung Elderly and Community Health Service (Portland, Victoria) respectively.

Abbreviations

- ACCHO

Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Organisation

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- HbA1C

Glycated Haemoglobin

- HREC

Human Research Ethics Committee

- IOR

Inner and Outer Regional

- NGO

Non-Government Organisation

- NHMRC

National Health and Medical Research Council

- QAAMS

Quality Assurance for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Medical Services

- RCTs

Randomised Controlled Trials

- SEWB

Social and Emotional Wellbeing

- T2DM

Type Two Diabetes Mellitus

Authors’ contributions

HB led the scoping review design, screening of data, data extraction, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript. MJB and CK were involved in the scoping review design, screening of data, data extraction, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. GE was involved in data extraction, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. JC and YP were involved in the analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. RC and VLV were involved in the scoping review design, analysis of data, and drafting of the manuscript which included a review for cultural appropriateness in the reporting of outcomes. VLV conceived the geographical aspect of the review and produced the geographical outputs and analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This review was part of a broader project which received funding from the Western Alliance Academic Health Science Centre (Project WA-733531_Beks). The funding body had no role in the design of the review, analysis and interpretation of articles. Robyn A Clark is supported by a Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (APP ID. 100847). Hannah Beks, Marley J Binder, Geraldine Ewing, and Vincent L Versace are funded by the Australian Government Department of Health Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training (RHMT) Program.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, Al-Yaman F, Bjertness E, King A, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples' health (the lancet–Lowitja Institute global collaboration): a population study. Lancet. 2016;388(10040):131–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander health performance framework 2017 report. Canberra: AHMAC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulver L, Ring I, Waldon W, Whetung V, Kinnon D, et al. Indigenous health – Australia, Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand and the United States - laying claim to a future that embraces health for us all. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) Contribution of chronic disease to the gap in adult mortality between aboriginal and Torres Strait islander and other Australians. Canberra: AIHW; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) Australian burden of disease study 2011: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2011. Canberra: AIHW; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 4727.0.55.006 - Australian aboriginal and Torres Strait islander health survey: updated results, 2012–13. Canberra: ABS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brimblecombe J, Ferguson M, Liberato S, O'Dea K. Characteristics of the community-level diet of aboriginal people in remote northern Australia. Med J Aust. 2013;198(7):380–384. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davy C, Harfield S, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A. Access to primary health care services for indigenous peoples: a framework synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):163. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0450-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Commonwealth of Australia . Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Closing the gap prime Minister's report 2018. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudgeon PW, Walker R, Scrine C, Shepherd CCJ, Calma T, et al. Effective strategies to strengthen the mental health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Canberra: Closing the Gap Clearinghouse; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charles J. An evaluation and comprehensive guide to successful aboriginal health promotion. Austr Indigen Health Bull. 2015;16(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson S. Evaluating indigenous programs: a toolkit for change. Evaluating indigenous programs: a toolkit for change. The Centre for Independent Studies. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson S. Mapping the indigenous program and funding maze. Centre for Independent Studies. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNICEF, World Health Organisation, International conference on primary health care . Declaration of Alma-Ata: international conference on primary health care. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Browne J, Adams K, Atkinson P, Gleeson D, Hayes R. Food and nutrition programs for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians: an overview of systematic reviews. Aust Health Rev. 2017;17(4):1–9. doi: 10.1071/AH17082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United Nations General Assembly . United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. New York: United Nations General Assembly; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genat B, Browne J, Thorpe S, MacDonald C. Sectoral system capacity development in health promotion: evaluation of an aboriginal nutrition program. Health Promot J Austr. 2016;27(3):236–242. doi: 10.1071/HE16044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marley JV, Kitaura T, Atkinson D, Metcalf S, Maguire GP, et al. Clinical trials in a remote aboriginal setting: lessons from the BOABS smoking cessation study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):579. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farnbach S, Eades AM, Fernando JK, Gwynn JD, Glozier N, et al. The quality of Australian indigenous primary health care research focusing on social and emotional wellbeing: a systematic review. Public Health Res Pract. 2017;27(4):e27341700. doi: 10.17061/phrp27341700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelaher M, Luke J, Ferdinand A, Chamravi D, Ewen S, et al. An evaluation framework to improve aboriginal and Torres Strait islander health. Report. Carlton: Lowitja Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morley S. What works in effective indigenous community-managed programs and organisations. Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beks H, Binder M, Kourbelis C, May N, Clark R, et al. Geographical analysis of evaluated chronic disease programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the primary healthcare setting: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(12):2268–2278. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Baldini Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. Chapter 11: scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs institute Reviewer's manual: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/. Accessed 16 Jan 2019.

- 24.National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Values and ethics: guidelines for ethical conduct in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Health Research: NHMRC; 2003. https://nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/values-and-ethics-guidelines-ethical-conduct-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-research. Accessed 19 Jan 2019

- 25.Jamieson L, Paradies Y, Eades S, Chong A, Maple-Brown L, et al. Ten principles relevant to health research among indigenous Australian populations. Med J Aust. 2012;197(1):16–18. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) Arc GIS arc map: release 10.6. Redlands: ESRI; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Remoteness structure. Canberra: ABS; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales (AHaMR) 10 out of 10 deadly health stories: nutrition and physical activity: successful program from NSW aboriginal community controlled health services. Surry Hills: AHaMR; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbott P, Davison J, Moore L, Rubinstein R. Barriers and enhancers to dietary behaviour change for aboriginal people attending a diabetes cooking course. Health Promot J Austr. 2010;21(1):33–38. doi: 10.1071/HE10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abbott PA, Davison JE, Moore LF, Rubinstein R. Effective nutrition education for aboriginal Australians: lessons from a diabetes cooking course. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams K, Rumbiolo D, Charles S. Evaluation of Rumbalara's 'No more Dhonga' short course in giving up smokes. Aborig Isl Health Work J. 2006;30(5):20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Askew DA, Togni SJ, Schluter PJ, Rogers L, Egert S, et al. Investigating the feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness of outreach case management in an urban aboriginal and Torres Strait islander primary health care service: a mixed methods exploratory study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:178. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1428-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailie RS, Robinson G, Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan SN, Halpin S, Wang Z. Investigating the sustainability of outcomes in a chronic disease treatment programme. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(6):1661–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballestas T, McEvoy S, Swift-Otero V, Unsworth M. A metropolitan aboriginal podiatry and diabetes outreach clinic to ameliorate foot-related complications in aboriginal people. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38(5):492–493. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrett E, Salem L, Wilson S, O'Neill C, Davis K, et al. Chronic kidney disease in an aboriginal population: a nurse practitioner-led approach to management. Aust J Rural Health. 2015;23(6):318–321. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Battersby MW, Kit JA, Prideaux C, Harvey PW, Collins JP, et al. Implementing the flinders model of self-management support with aboriginal people who have diabetes: findings from a pilot study. Aust J Prim Health. 2008;14(1):66–74. doi: 10.1071/PY08009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyle J, Hollands G, Beck S, Hampel G, Wapau H, et al. Process evaluation of a pilot evidence-based polycystic ovary syndrome clinic in the Torres Strait. Aust J Rural Health. 2017;25(3):175–181. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brazionis L, Jenkins A, Keech A, Ryan C, Brown A, et al. Diabetic retinopathy in a remote indigenous primary healthcare population: a central Australian diabetic retinopathy screening study in the telehealth eye and Associated Medical Services network project. Diabet Med. 2018;35(5):630–639. doi: 10.1111/dme.13596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burgess CP, Bailie RS, Connors CM, Chenhall RD, McDermott RA, et al. Early identification and preventive care for elevated cardiovascular disease risk within a remote Australian aboriginal primary health care service. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canuto K, Cargo M, Li M, D’Onise K, Esterman A, McDermott R. Pragmatic randomised trial of a 12-week exercise and nutrition program for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women: clinical results immediate post and 3 months follow-up. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):933. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canuto K. Evaluating the effectiveness of the aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Women’s fitness program: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Adelaide: University of South Australia; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canuto KJ, Spagnoletti B, McDermott RA, Cargo M. Factors influencing attendance in a structured physical activity program for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women in an urban setting: a mixed methods process evaluation. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan LC, Ware R, Kesting J, Marczak M, Good D, et al. Short term efficacy of a lifestyle intervention programme on cardiovascular health outcome in overweight indigenous Australians with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. The healthy lifestyle programme (HELP) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clark RA, Fredericks B, Adams M, Howie-Esquivel J, Dracup K, et al. A collaborative approach to developing culturally appropriate heart failure self-care tools for indigenous Australians using multi-media technology. Circulation. 2014;130(Suppl 2):A13530. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark RA, Fredericks B, Buitendyk NJ, Adams MJ, Howie-Esquivel J, et al. Development and feasibility testing of an education program to improve knowledge and self-care among aboriginal and Torres Strait islander patients with heart failure. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(3):3231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clifford A, Shakeshaft A, Deans C. Training and tailored outreach support to improve alcohol screening and brief intervention in aboriginal community controlled health services. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32(1):72–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crengle S, Luke JN, Lambert M, Smylie JK, Reid S, et al. Effect of a health literacy intervention trial on knowledge about cardiovascular disease medications among indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e018569. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D'Abbs P, Togni S, Rosewarne C, Boffa J. The grog mob: lessons from an evaluation of a multi-disciplinary alcohol intervention for aboriginal clients. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37(5):450–456. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davey M, Moore W, Walters J. Tasmanian aborigines step up to health: evaluation of a cardiopulmonary rehabilitation and secondary prevention program. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:349. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DiGiacomo M, Davidson PM, Davison J, Moore L, Abbott P. Stressful life events, resources, and access: key considerations in quitting smoking at an aboriginal medical service. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(2):174–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dimer L, Jones J, Dowling T, Cheetham C, Maiorana A, et al. Heart health: new ways to deliver cardiac rehabilitation. Aust Nurs J. 2010;18(6):41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dimer L, Jones J, Dowling T, Cheetham C, Maiorana A, et al. Heart health for our people by our people: a culturally appropriate WA CR program. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21(10):651–652. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dimer L, Dowling T, Jones J, Cheetham C, Thomas T, et al. Build it and they will come: outcomes from a successful cardiac rehabilitation program at an aboriginal medical service. Aust Health Rev. 2013;37(1):79–82. doi: 10.1071/AH11122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maiorana A, Dimer L, Dowling T, Jones J, Thomas T, et al. Outcomes from an aboriginal medical service based cardiac rehabilitation program. Heart Lung Circ. 2012;21(10):659. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.07.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maiorana A, Chevis E, Venables M, Dubrawski K, Dowling T, et al. Reducing inequities in aboriginal Australian heart health through culturally specific cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22(1):15. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eades SJ, Sanson-Fisher RW, Wenitong M, Panaretto K, D'Este C, et al. An intensive smoking intervention for pregnant aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2012;197(1):42–46. doi: 10.5694/mja11.10858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gould G, McGechan A, Van der Zwan R. Proceedings of the 10th National Rural Health Conference, 2009 May 17–20. Cains: National Rural Health Alliance; 2009. Give up the smokes - a smoking cessation program for indigenous Australians. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gracey M, Bridge E, Martin D, Jones T, Spargo RM, et al. An aboriginal-driven program to prevent, control and manage nutrition-related “lifestyle” diseases including diabetes. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2006;15(2):178–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isaacs A, Lampitt B. The Koorie Men's health day: an innovative model for early detection of mental illness among rural aboriginal men. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22(1):56–61. doi: 10.1177/1039856213502241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ju X, Brennan D, Parker E, Mills H, Kapellas K, Jamieson L. Efficacy of an oral health literacy intervention among indigenous Australian adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemio. 2017;45(5):413–426. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kapellas K, Do LG, Mark Bartold P, Skilton MR, Maple-Brown LJ, et al. Effects of full-mouth scaling on the periodontal health of indigenous Australians: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(11):1016–1024. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kapellas K, Maple-Brown LJ, Bartold PM, Brown A, O'Dea K, et al. O162 effect of a periodontal intervention on pulse wave velocity in indigenous Australians with periodontal disease: the PerioCardio randomised controlled trial. Glob Heart. 2014;9(Suppl 1):44. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.1368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kapellas K, Maple-Brown LJ, Jamieson LM, Do LG, O'Dea K, et al. Effect of periodontal therapy on arterial structure and function among aboriginal Australians: a randomised, controlled trial. Hypertension. 2014;64(4):702–708. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kapellas K, Mejia G, Bartold PM, Skilton MR, Maple-Brown LJ, et al. Periodontal therapy and glycaemic control among individuals with type 2 diabetes: reflections from the PerioCardio study. Int J Dent Hyg. 2017;15(4):42–51. doi: 10.1111/idh.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kowanko I, Helps Y, Harvey P, Battersby M, McCurry B, et al. Chronic condition management strategies in aboriginal communities: final report 2011. Adelaide: Flinders University and the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lawton P, Wright G, Hore B, McLaughlin J, Cass A. Analysis of longitudinal clinical data to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of a nurse-led Ckd program. Nephrology. 2016;21:104. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Longstreet D, Heath D, Savage I, Vink R, Panaretto K. Estimated nutrient intake of urban indigenous participants enrolled in a lifestyle intervention program. Nutr Diet. 2008;65(2):128–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0080.2008.00253.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marley JV, Atkinson D, Kitaura T, Nelson C, Gray D, et al. The be our ally beat smoking (BOABS) study, a randomised controlled trial of an intensive smoking cessation intervention in a remote aboriginal Australian health care setting. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McDermott RA, Schmidt B, Preece C, Owens V, Taylor S, et al. Community health workers improve diabetes care in remote Australian indigenous communities: results of a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:68. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0695-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schmidt B, Campbell S, McDermott R. Community health workers as chronic care coordinators: evaluation of an Australian indigenous primary health care program. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40(Suppl 1):107–114. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Segal L, Nguyen H, Schmidt B, Wenitong M, McDermott RA. Economic evaluation of indigenous health worker management of poorly controlled type 2 diabetes in North Queensland. Med J Aust. 2016;204(5):1961. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mills K, Gatton ML, Mahoney R, Nelson A. 'Work it out': evaluation of a chronic condition self-management program for urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, with or at risk of cardiovascular disease. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):680. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2631-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nagel T, Thompson C. Motivational care planning: self-management in indigenous mental health. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37(12):996–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nagel T, Robinson G, Trauer T, Condon J. An approach to treating depressive and psychotic illness in indigenous communities. Aust J Prim Health. 2008;14(1):17–24. doi: 10.1071/PY08003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quinn E, O'Hara BJ, Ahmed N, Winch S, McGill B, et al. Enhancing the get healthy information and coaching service for aboriginal adults: evaluation of the process and impact of the program. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):168. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0641-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Read P, Lothian R, Chronister K, Gilliver R, Kearley J, et al. Delivering direct acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C to highly marginalised and current drug injecting populations in a targeted primary health care setting. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shephard MDS. Cultural and clinical effectiveness of the 'QAAMS' point-of-care testing model for diabetes management in Australian aboriginal medical services. Clin Biochem Rev. 2006;27(3):161–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shephard M, Shephard A, McAteer B, Regnier T, Barancek K. Results from 15years of quality surveillance for a National Indigenous Point-of-Care Testing Program for diabetes. Clin Biochem. 2017;50(18):1159–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Spaeth BA, Shephard MD, Schatz S. Point-of-care testing for haemoglobin A1c in remote Australian indigenous communities improves timeliness of diabetes care. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(4):2849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shephard MDS, Mazzachi BC, Shephard AK, Burgoyne T, Dufek A, et al. Point-of-care testing in aboriginal hands - a model for chronic disease prevention and management in indigenous Australia. Point Care. 2006;5(4):168–176. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sinclair C, Stokes A, Jeffries-Stokes C, Daly J. Positive community responses to an arts–health program designed to tackle diabetes and kidney disease in remote aboriginal communities in Australia: a qualitative study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40(4):307–312. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ski C, Vale M, Thompson D, Jelinek M, Scott I, et al. The coaching patients on achieving cardiovascular health (COACH) Programme: reducing the treatment gap between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. Heart Lung Circ. 2017;26(Suppl 2):336. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2017.06.680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spurling GKP, Askew DA, Hayman NE, Hansar N, Cooney AM, et al. Retinal photography for diabetic retinopathy screening in indigenous primary health care: the Inala experience. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34(Suppl 1):30–S3. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spurling GKP, Hayman NE, Cooney AL. Adult health checks for indigenous Australians: the first year's experience from the Inala indigenous health service. Med J Aust. 2009;190(10):562–564. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stevens JA, Dixon J, Binns A, Morgan B, Richardson J, Egger G. Shared medical appointments for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander men. Aust Fam Physician. 2016;45(6):425–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sun J, Buys N. Effectiveness of participative community singing intervention program on promoting resilience and mental health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. In: Olisah V, editor. Essential notes in psychiatry. Croatia: InTech; 2012. pp. 245–252. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sun J, Buys N. Participatory community singing program to enhance quality of life and social and emotional well-being in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians with chronic diseases. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2013;12(3):317–323. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sun J, Buys N. Effectiveness of a participative community singing program to improve health behaviors and increase physical activity in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2013;12(3):297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sun J, Buys N. Can community singing program promote social and emotional wellbeing in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians? J Altern Complement. 2013;5(2):137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sun J, Buys NJ. Improving aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians ' well-being using participatory community singing approach. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2013;12(3):305–316. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sun J, Buys N. Using participative community singing program to improve health behaviours in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;5(2):103–109. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sun J, Buys N. Using community singing as a culturally appropriate approach to prevent depression in aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;5(2):111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sun J, Buys N. Effects of community singing program on mental health outcomes of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a meditative approach. Am J Health Promot. 2016;30(4):259–263. doi: 10.1177/0890117116639573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Swain L. Improving medication management for aboriginal and Torres islander people by investigating the use of Home medicines review. Sydney: University of Sydney; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Swain LS, Barclay L. Exploration of aboriginal and Torres Strait islander perspectives of Home medicines review. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15:3009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tane MP, Hefler M, Thomas DP. An evaluation of the “Yaka Ŋarali” tackling indigenous smoking program in East Arnhem Land: Yolŋu people and their connection to ŋarali’. Health Promot J Austr. 2018;29(1):10–17. doi: 10.1002/hpja.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Togni SJ. The Uti Kulintjaku project: the path to clear thinking. An evaluation of an innovative, aboriginal-led approach to developing bi-cultural understanding of mental health and wellbeing. Aust Psychol. 2017;52(4):268–279. doi: 10.1111/ap.12243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]