ALV consists of several subgroups that are particularly characterized by their receptor usage, which subsequently dictates the host range and tropism of the virus. A few newly emerging and highly pathogenic Chinese ALV strains have recently been suggested to be an independent subgroup, ALV-K, based solely on their genomic sequences. Here, we performed a series of experiments with the ALV-K strain JS11C1, which showed its dependence on the Tva cell surface receptor. Due to the sharing of this receptor with ALV-A, both subgroups were able to interfere with superinfection. Because ALV-K could become an important pathogen and a significant threat to the poultry industry in Asia, the identification of a specific receptor could help in the breeding of resistant chicken lines with receptor variants with decreased susceptibility to the virus.

KEYWORDS: avian leukosis virus K, Tva, host range, resistance/susceptibility to retrovirus, retrovirus receptor, superinfection interference

ABSTRACT

Avian leukosis virus subgroup K (ALV-K) is composed of newly emerging isolates, which, in sequence analyses, cluster separately from the well-characterized subgroups A, B, C, D, E, and J. However, it remains unclear whether ALV-K represents an independent ALV subgroup with regard to receptor usage, host range, and superinfection interference. In the present study, we examined the host range of the Chinese infectious isolate JS11C1, an ALV-K prototype, and we found substantial overlap of species that were either resistant or susceptible to ALV-A and JS11C1. Ectopic expression of the chicken tva gene in mammalian cells conferred susceptibility to JS11C1, while genetic ablation of the tva gene rendered chicken DF-1 cells resistant to infection by JS11C1. Thus, tva expression is both sufficient and necessary for JS11C1 entry. Receptor sharing was also manifested in superinfection interference, with preinfection of cells with ALV-A, but not ALV-B or ALV-J, blocking subsequent JS11C1 infection. Finally, direct binding of JS11C1 and Tva was demonstrated by preincubation of the virus with soluble Tva, which substantially decreased viral infectivity in susceptible chicken cells. Collectively, these findings indicate that JS11C1 represents a new and bona fide ALV subgroup that utilizes Tva for cell entry and binds to a site other than that for ALV-A.

IMPORTANCE ALV consists of several subgroups that are particularly characterized by their receptor usage, which subsequently dictates the host range and tropism of the virus. A few newly emerging and highly pathogenic Chinese ALV strains have recently been suggested to be an independent subgroup, ALV-K, based solely on their genomic sequences. Here, we performed a series of experiments with the ALV-K strain JS11C1, which showed its dependence on the Tva cell surface receptor. Due to the sharing of this receptor with ALV-A, both subgroups were able to interfere with superinfection. Because ALV-K could become an important pathogen and a significant threat to the poultry industry in Asia, the identification of a specific receptor could help in the breeding of resistant chicken lines with receptor variants with decreased susceptibility to the virus.

INTRODUCTION

Avian leukosis virus (ALV), which is found as an exogenous or endogenous virus in domestic chickens, consists of six phylogenetically related subgroups (A, B, C, D, E, and J). These subgroups have traditionally been classified by the host range, antibody neutralization, and interference in superinfection experiments (1). Once the cellular receptors responsible for susceptibility to ALV were identified (see reference 2 for a review), subgroup-specific receptor usage became the unequivocal criterion. Subgroup A ALVs enter the cell through Tva, a protein that belongs to the family of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors (3, 4). Subgroup C ALVs utilize the Tvc protein, a member of the butyrophilin family that is distinguished by two immunoglobulin-like domains (5). The Tvj protein is utilized by subgroup J and has been identified as chicken Na+/H+ exchanger type 1 (NHE1), which is characterized by its 12 predicted transmembrane segments and a prominent extracellular loop 1 (6). Subgroups B, D, and E share the Tvb receptor, a tumor necrosis factor receptor-related protein (7–9). As would be expected, this receptor sharing leads to strong interference between the B and D subgroups. Subgroup E is special, in that it does not interfere with subgroup B or D superinfection, but cells preinfected with subgroup B or D ALVs have been shown to become resistant to subgroup E superinfection. These findings can be explained by the existence of two functionally distinct Tvb forms (10) and nonoverlapping sites for B, D, and E envelope glycoprotein interactions with the Tvb receptor. Correspondingly, different amino acid sequences, which are known to be critical for subgroup B and E binding, have been described previously (11, 12).

This receptor usage diversification, which has also been observed for murine and feline leukemia viruses (13, 14), can be explained by mutual selection forces that are imposed by the retrovirus on the host and vice versa. The host escapes this selection force via the evolution of receptor variants that exhibit decreased or even abrogated binding to retroviral envelopes. Numerous ALV-resistant receptor alleles have been described (5, 15–17), and positive selection was demonstrated to act within the extracellular loop 1 of NHE1, the critical region for ALV-J susceptibility (18). We have also identified receptor variants that lead to decreased susceptibility to avian sarcoma and leukosis virus (ASLV) infection (19, 20). ALV evolution might have proceeded through such receptors with decreased susceptibility and/or ALV escape mutants with extended host usage (21–24), eventually leading to the development of new strains whose surface glycoproteins bind to the variant receptors or new cell surface molecules.

The last additions to the complexity of ALVs are the new strains that have been isolated from the native Chinese chicken breed Luhua, which display rather low gp85 homology (∼80% amino acids), compared to ALV subgroups A to E (25). The molecularly cloned and infectious strain JS11C1 (25) is a prototype of this new virus cluster, which also includes other strains found in the Chinese Luhua chicken, the unique Taiwanese strain TW-3593 (26), and Japanese fowl glioma viruses (27–30). The heterogeneity of this virus cluster has been further underlined by recombinant isolates, e.g., TymS_90 and TW3577, that have been scored as ALV-A strains based on their gp85 sequences (25). Recent epidemiological investigations have revealed that these new ALVs, along with ALV-J, ALV-A, and ALV-B strains, are quite widespread among indigenous chicken breeds (31). The biological characteristics and pathogenic capacity of these new virus strains remain to be understood.

After Cui and colleagues determined the sequence of the rescued clone JS11C1 (25), the authors postulated the discovery of a new ALV subgroup, ALV-K. This denomination was based solely on the divergent sequence of the env gene and the separate branching from ALV-A to -E strains. In order to understand the virus-cell interactions after JS11C1 infection, we performed host range experiments, examined superinfection interference with other ALV subgroups, and identified the receptor adopted for JS11C1 cell entry. Our results confirm that JS11C1 represents a separate ALV subgroup that exhibits a specific host range and a unique pattern of superinfection interference. In this study, we show that the chicken protein Tva serves as the specific receptor for ALV-K entry.

RESULTS

Host range of the RCAS vector with the JS11C1 envelope in wild avian species.

We studied infection of cells in vitro using the green fluorescent protein (GFP)-transducing ALV-based RCAS vector with the envelope from the JS11C1 ALV strain (25). We replaced the env gene of RCASBP(D)GFP with the complete JS11C1 env gene, which had been synthesized according to the published sequence (GenBank accession no. KF746200). The amino acid sequence of the JS11C1 envelope glycoprotein, together with other K subgroup strains, is shown in Fig. 1 and aligned to the sequence of ALV subgroup A. The resulting vector, RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP, produced an infectious virus titer of 106 infection units (IU) per ml in transfected DF-1 cells. A gradual increase of cultured GFP-positive DF-1 cells demonstrates viral replication in the cell culture (Fig. 2A). We simulated the cell susceptibility/resistance better with the replication-competent RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP vector than with a single-round infection vector.

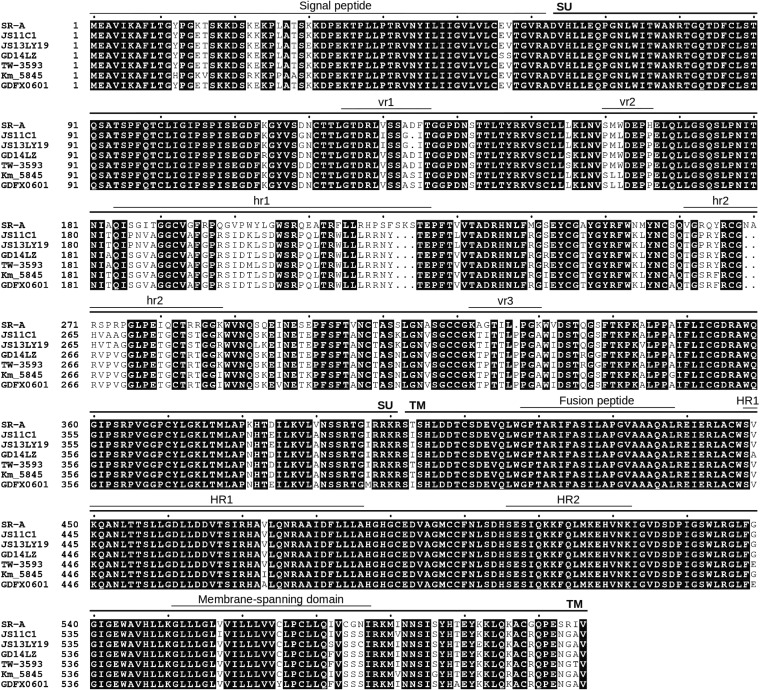

FIG 1.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the ALV subgroup A and subgroup K envelope glycoproteins. Amino acid sequences deduced from the available GenBank data are shown. Subgroup A is represented by the Schmidt-Ruppin A (SR-A) strain (GenBank accession no. NP040548), and subgroup K is represented by the Chinese and Taiwanese nonrecombinant strains JS11C1 (GenBank accession no. KF746200), JS13LY19 (GenBank accession no. AWO14321), GD14LZ (GenBank accession no. ANW72067), TW-3593 (GenBank accession no. ADP21276), Km_5845 (GenBank accession no. BAL70358), and GDFX0601 (GenBank accession no. AKP18446). Identical amino acids are highlighted in black. Gaps are indicated by dots. The main functional domains of envelope glycoproteins are delineated above the sequence. SU, surface subunit; TM, transmembrane subunit; vr1, vr2, and vr3, variable regions 1 to 3; hr1 and hr2, hypervariable regions 1 and 2; HR1 and HR2, heptad repeats 1 and 2.

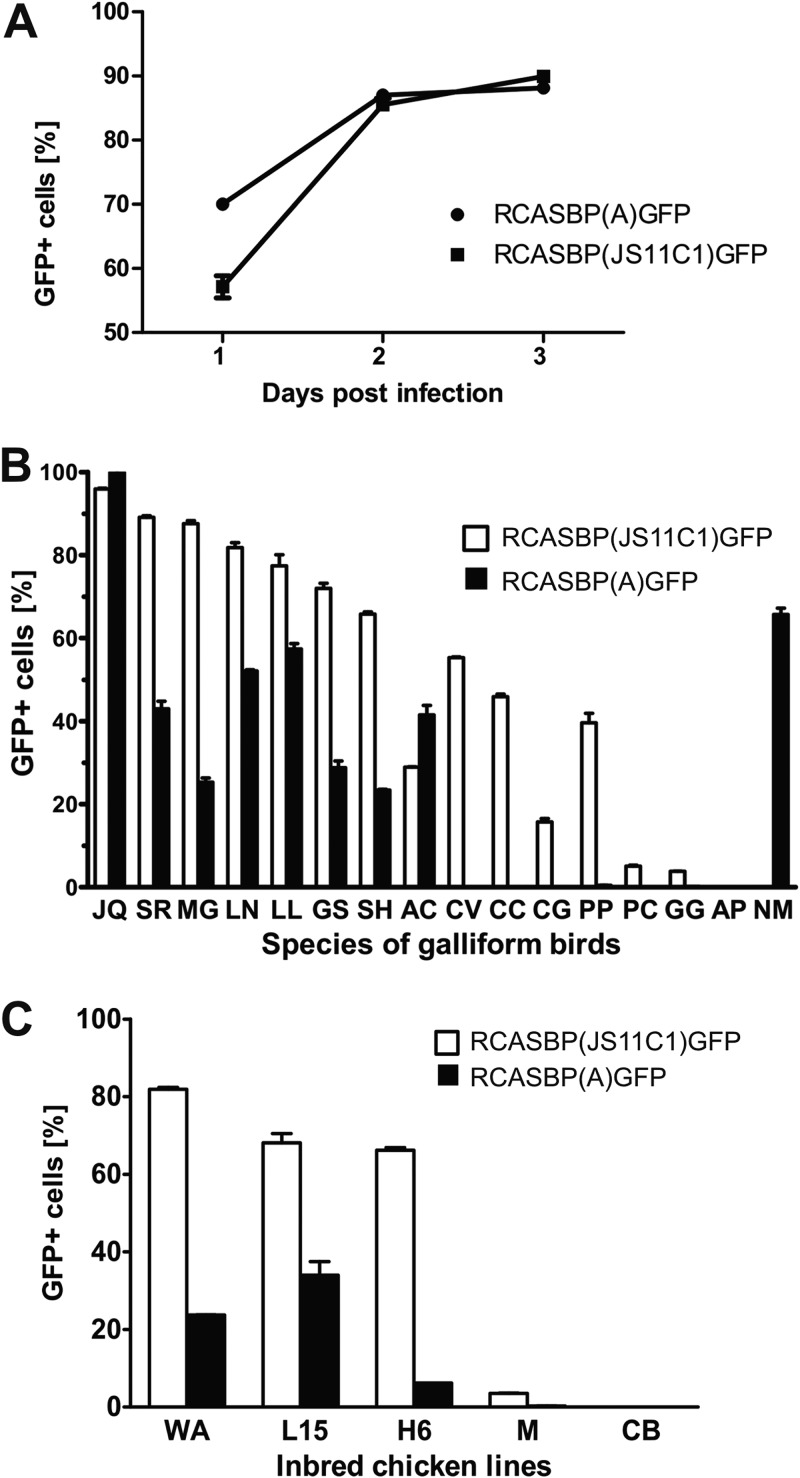

FIG 2.

Host range of RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP in galliform species and inbred lines of domestic chickens. (A) Time courses of RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP and RCASBP(A)GFP infection in DF-1 cells. The percentages of GFP-positive cells in the 3 consecutive days after infection are shown as means and standard deviations of triplicate assays. (B) Efficiency of RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP and RCASBP(A)GFP infection, measured as the percentages of GFP-positive cells 3 days after infection for cultured embryo fibroblasts of 14 galliform species (Reeve’s pheasant [SR], turkey [MG], silver pheasant [LN], white-crested kalij pheasant [LL], gray jungle fowl [GS], Mrs. Hume’s pheasant [SH], chukar [AC], northern bobwhite [CV], California quail [CC], Gambel’s quail [CG], gray partridge [PP], ringed-neck pheasant [PC], red jungle fowl [GG], and guinea fowl [NM]), QT6 cells representing the Japanese quail (JQ), and embryo fibroblasts of the domestic duck (AP). Results are shown as means ± standard deviations of duplicate assays. (C) Efficiency of RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP and RCASBP(A)GFP infection in cultured embryo fibroblasts of five inbred chicken lines. Results are shown as means ± standard deviations of duplicate assays.

We employed the RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP virus and cultured embryo fibroblasts of multiple galliform birds to screen for species that were susceptible or resistant to infection with the new ALV strain, JS11C1. Our panel of investigated species included Japanese quail, turkey, common ring-necked pheasant, Reeve’s pheasant, Mrs. Hume’s pheasant, silver pheasant, white-crested kalij pheasant, guinea fowl, chukar, gray partridge, northern bobwhite, California quail, Gambel’s quail, red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus subsp. murghi), and gray jungle fowl. The domestic duck, a nongalliform species that is known to be susceptible only to ALV subgroup C (32), was added as a control. In parallel, we infected cells with subgroup A virus RCASBP(A)GFP for comparison. As shown in Fig. 2B, Japanese quail QT6 cells were equally susceptible to the two viruses, with nearly all cells being GFP positive 3 days postinfection. Other bird species that were analyzed were gradually less susceptible to both RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP and RCASBP(A)GFP. In most species, the spread of RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP was quicker than that of RCASBP(A)GFP. In addition, three species of New World quails, along with the common ringed-neck pheasant and gray partridge, displayed decreased susceptibility to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP and complete or almost complete resistance to subgroup A. The resistance to subgroup A was previously described in New World quails and was attributed to W48S substitution within the specific Tva receptor (18). Interestingly, two closely related species of jungle fowls differed substantially, with the gray jungle fowl being infected efficiently with RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP but less efficiently with subgroup A (30% GFP-positive cells). The red jungle fowl was marginally susceptible to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP (1.5% to 4% GFP-positive cells) and nearly resistant to subgroup A (Fig. 2B). This resistance to subgroup A was noted previously and was explained by the decreased Tva display that occurred due to an intronic deletion of the branching point signal in the tva gene and the resulting intron retention (20). Guinea fowl cells were quite exceptional, being highly susceptible to subgroup A but resistant to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP. As expected, the domestic duck turned out to be resistant to both viruses (Fig. 2B). In summary, the RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP host range includes many galliform bird species, with the exception of the guinea fowl. Although similar to the host range of RCASBP(A)GFP in many respects, these differences suggest an independent subgroup specificity for the JS11C1 ALV strain.

Host range of the RCAS vector with the JS11C1 envelope in inbred lines of domestic chickens.

We surveyed the susceptibility or resistance to JS11C1 in vitro in a panel of inbred chicken lines whose receptors for ALV subgroups had been characterized previously (5, 16, 19, 20). We examined cultured embryo fibroblasts of lines WA, L15, H6, M, and CB. In WA, L15, and H6, we observed weak to medium-level susceptibility to RCASBP(A)GFP and strong susceptibility (70 to 80% GFP-positive cells) to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, the M embryo fibroblasts exhibited nearly complete resistance to the A subgroup and were marginally susceptible to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP (Fig. 2C). This is similar to the pattern that has been observed for red jungle fowl, which has the same intronic deletion in the tva gene as the M line (20). As expected, the CB line was completely resistant to RCASBP(A)GFP, in accordance with the C40W substitution in Tvar that has been described previously (16). Furthermore, the CB line turned out to be completely resistant also to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP (Fig. 2C). In conclusion, these findings suggest that the A subgroup might share the receptor molecule Tva with JS11C1. This would explain the concurrent resistance or decreased susceptibility to both RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP when Tva is inactivated in the CB line or inefficiently produced in the M line and red jungle fowl.

Tva is sufficient for RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP entry.

To confirm or to refute the hypothesis of Tva as a receptor for JS11C1 cell entry, we tested whether ectopic Tva expression in cells of a resistant species would confer susceptibility to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP. For this purpose, we stably inserted expression vectors with chicken tva into NIL-2 cells of the Syrian hamster, a species that is completely resistant to ALV infection. As a control, we used NIL-2 cells that ectopically express chicken Tvc, the receptor for the ALV-C subgroup. The chicken DF-1 cell line and the NIL-Tva and NIL-Tvc clones were then infected with RCASBP(A)GFP, RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP, RCASBP(C)GFP, and RCASBP(B)GFP (Fig. 3A). DF-1 cells were efficiently infected with A, B, and C subgroups and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP. NIL-Tva cells were susceptible to the A subgroup and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP but not to the B and C subgroups. In addition, we found that NIL-Tvc cells were susceptible only to the C subgroup and not to the A and B subgroups or RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP. Hence, we conclude that tva expression simultaneously conferred susceptibility to ALV-A and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP.

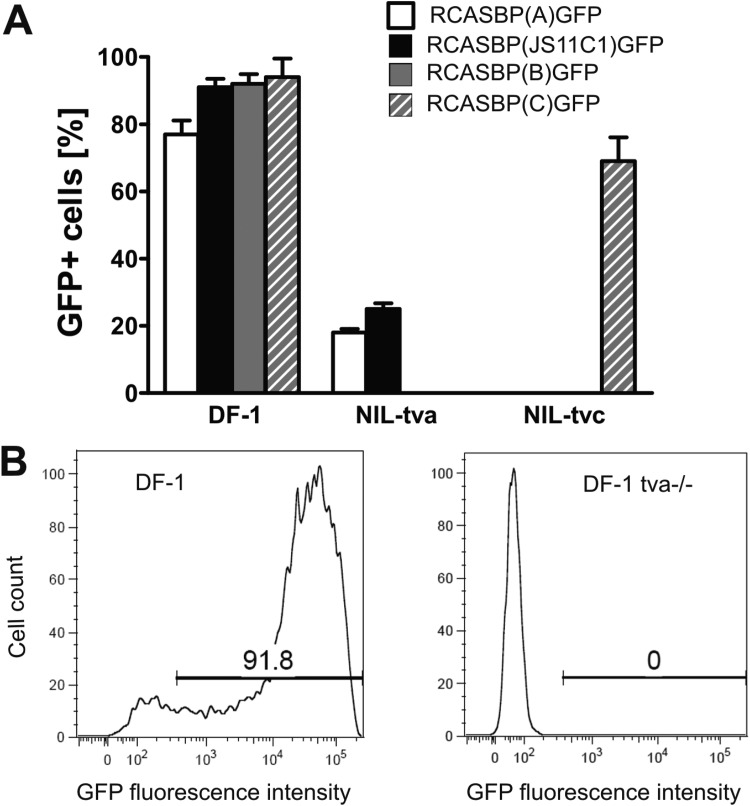

FIG 3.

Expression of the tva gene is sufficient and necessary for RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP infection. (A) Efficiency of RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP and RCASBP(A)GFP infection in the Syrian hamster cell line NIL-2 ectopically expressing the tva gene (NIL-Tva). DF-1 cells were used as a susceptible control. Viruses with B and C specificity, i.e., RCASBP(B)GFP and RCASBP(C)GFP, respectively, and NIL-2 cells ectopically expressing the tvc gene were used as independent controls. Infection efficiencies are shown as percentages of GFP-positive cells and are presented as means ± standard deviations of triplicate assays. (B) Efficiency of RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP infection in intact DF-1 cells (left) and DF-1 cells with a frameshift mutation in the tva gene (right), presented as FACS histograms of GFP-negative and GFP-positive cells. The relative GFP fluorescence is plotted against the cell count, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells is indicated. Typical results from triplicate assays are shown.

Tva null chicken cells are resistant to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP infection.

Having shown that Tva expression is sufficient for cell susceptibility to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP, we tested the effect of Tva depletion in susceptible cells. We introduced a null mutation into the endogenous tva gene of DF-1 cells, which are susceptible to both RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP (Fig. 2A and 3A). We employed the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system and prepared a DF-1-tva−/− cell clone with a homozygous frameshift deletion within tva (33). DF-1-tva−/− cells were then infected with RCASBP(A)GFP, RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP, RCASBP(C)GFP, and RCASBP(B)GFP. The null mutation of tva abrogated the susceptibility of DF-1 cells to the A subgroup and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP (Fig. 3B) but not that to the C and B subgroups (data not shown). Hence, we conclude that functional Tva is required for RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP entry. Together with the previous finding that Tva is sufficient for the entry of RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP, we have determined that subgroup A ALVs and JS11C1 share the Tva molecule as the cell surface receptor.

Superinfection interference between subgroup A and JS11C1 ALVs.

For our superinfection experiments, we constructed new RCAS vectors that contained the dsRed fluorescent marker and exhibited subgroup A and K specificity, i.e., RCASBP(A)dsRed and RCASBP(JS11C1)dsRed, respectively. The availability of RCASBP(A)dsRed and RCASBP(JS11C1)dsRed vectors and the RCAS vectors with GFP fluorescent markers enabled preinfection and superinfection with viruses expressing different fluorescent reporters, followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of GFP-positive, dsRed-positive, and GFP/dsRed-double-positive cells.

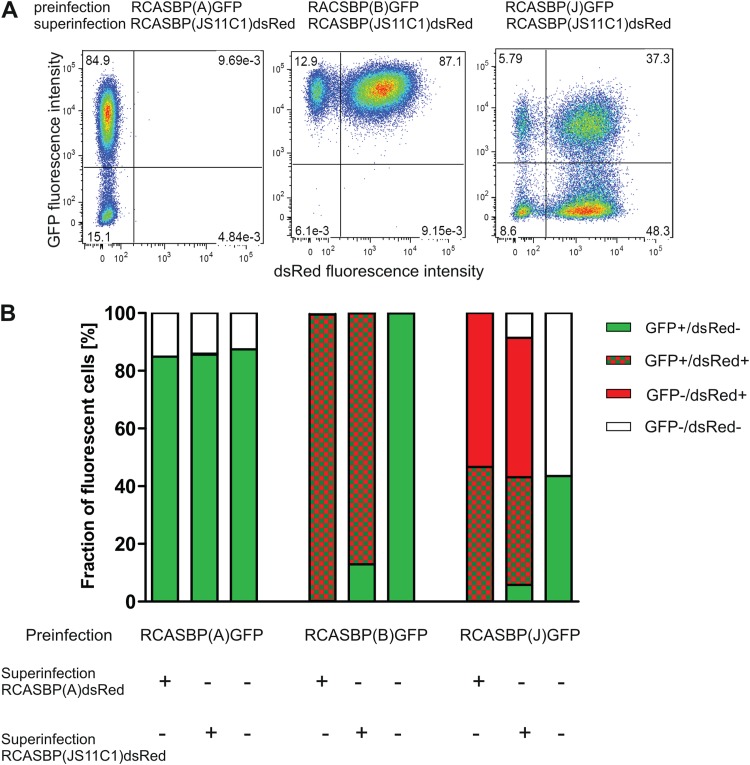

In the superinfection interference experiment, we preinfected DF-1 cells with RCASBP(A)GFP and challenged the cells with RCASBP(A)dsRed or RCASBP(JS11C1)dsRed after 1 week. In both cases, subgroup A preinfection resulted in ∼85% GFP-positive cells and almost completely blocked superinfection, as indicated by the absence of GFP/dsRed-double-positive cells (Fig. 4A and B). Roughly 15% of the cells remained resistant to both preinfection and superinfection challenge, which we suspect was due to a replication-competent GFP-defective mutant virus that arose during the long preinfection phase. As a control, we preinfected DF-1 cells with either RCASBP(B)GFP or RCASBP(J)GFP and applied the RCASBP(A)dsRed or RCASBP(JS11C1)dsRed virus as the superinfection challenge. The subgroup B virus preinfected DF-1 cells very efficiently, and nearly all cells could be superinfected with subgroup A or subgroup K (99.8% and 87%, respectively) (Fig. 4A and B). The subgroup J virus, according to our previous data (17), preinfected DF-1 cells slowly, with roughly one-half of the cells remaining GFP negative. The subsequent superinfection with RCASBP(A)dsRed or RCASBP(JS11C1)dsRed was not interfered with by the preinfection, resulting in generation of ∼50% GFP/dsRed-double-positive and dsRed-single-positive cells (Fig. 4A and B). These results demonstrate strong interference between the A and K ALV subgroups, which again suggests that viruses of both subgroups use the Tva receptor to enter the host cell.

FIG 4.

Superinfection interference between ALV-A and ALV-K subgroups. (A) Results of interference experiments shown as FACS dot plots. Preinfection of DF-1 cells with RCASBP(A)GFP blocks superinfection with RCASBP(JS11C1)dsRed (left), whereas preinfection with RCASBP(B)GFP (middle) or RCASBP(J)GFP (right) permits subsequent superinfection with RCASBP(JS11C1)dsRed. Horizontal axes, dsRed positivity; vertical axes, GFP positivity. (B) Efficiency of superinfection interference between RCASBP(A)GFP, RCASBP(B)GFP, and RCASBP(J)GFP as preinfection viruses and RCASBP(A)dsRed and RCASBP(JS11C1)dsRed as superinfection viruses. The results are shown as mean percentages of GFP-negative/dsRed-negative, GFP-positive/dsRed-negative, GFP-negative/dsRed-positive, and GFP-positive/dsRed-positive cells, measured in triplicate.

Soluble Tva competes with RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP virus infection.

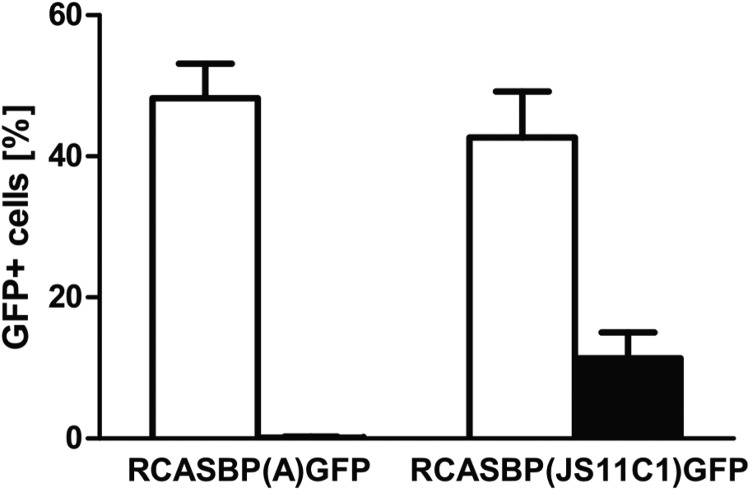

To demonstrate the direct interaction of the Tva receptor with the ALV-K envelope, we employed the soluble form of the ALV-A receptor (soluble Tva [sTva]) fused with a mouse immunoglobulin heavy chain (mouse IgG [mIgG]), immunoadhesin sTva-mIgG, which has been described previously (22, 34, 35). sTva-mIgG was assayed for its affinity to bind the cell-free RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP virus, as well as its capacity to compete with cell entry. Preincubation of the RCASBP(A)GFP virus with sTva-mIgG completely abrogated the subsequent infection of DF-1 cells. Similarly, preincubation of RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP with sTva-mIgG decreased viral infection to 23% of that of the control mock-incubated virus in culture medium without sTva-mIgG (Fig. 5). This assay is based on direct binding of the soluble receptor and virus glycoprotein. Hence, we have established independent confirmation that the subgroup A ALV and the JS11C1 virus share the Tva molecule as a host cell receptor.

FIG 5.

Soluble Tva interference with ALV-A and ALV-K infection in susceptible cells. RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP viruses were preincubated (filled columns) or mock-incubated (empty columns) with sTva-mIgG immunoadhesin and used for infection of DF-1 cells. Infection efficiencies are shown as means ± standard deviations of percentages of GFP-positive cells; the experiment was performed in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used several independent assays to show that a newly emerging ALV, the Chinese isolate JS11C1, enters chicken host cells through Tva, a receptor that has been long known for A subgroup ALVs (3, 4). We demonstrated that Tva is both necessary and sufficient for JS11C1 virus entry by ectopic tva expression in nonpermissive cells and by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated tva knockout in permissive chicken cells, respectively. This conclusion was corroborated by direct binding of the soluble receptor and virus glycoprotein. Sharing Tva as a receptor molecule results in strong superinfection interference between ALV subgroup A and JS11C1. This receptor sharing is not unique among retroviruses, as ALV subgroups B, D, and E use the same Tvb receptor (7–9) and human endogenous retrovirus W shares its ASCT2 receptor with multiple unrelated endogenous betaretroviruses (36–38). In general, receptor interference has been used to classify retroviruses into distinct interference groups (39).

In previous studies (25, 31, 40, 41), a handful of new Chinese and Taiwanese isolates were classified as ALV subgroup K based on their gp85 phylogenetic relationships to ALV subgroups A, B, C, D, E, and J. As an important common pattern of all these phylogenies, all ALV-K env sequences cluster together and separate from those in subgroups A to E. The terminal tree branches of the subgroup K cluster are short, indicating a historically recent spread of these isolates. However, inferring retroviral evolutionary history based on the phylogeny of a single gene should be regarded with caution, due to the frequent recombination of retroviral genomes. Indeed, some of the newly reported ALV isolates are recombinants (25). Also, the position of ALV-K, relative to other subgroups, in the various env-based phylogenies published varies considerably. Additional studies of novel whole-genome sequences, together with recombination analyses, will be necessary to gain further insight into the ALV-K origin.

With the ALV-K denomination based solely on env sequences, it remains to be seen whether this subgroup characteristically differs from the other subgroups, particularly in host range, receptor usage, and superinfection interference. Our identification of Tva as a specific receptor for the JS11C1 virus, a representative of the new isolates, and demonstration of the strong superinfection interference between the A subgroup and JS11C1 suggest identical subgroup specificity. The difference in the host range, as observed for the guinea fowl, New World quails, and gray partridge, might result from different virus-binding sites used by the A subgroup ALV and JS11C1. This would resemble the situation of the Tvb receptor and the interference between B, D, and E subgroups (11, 12). The JS11C1 virus-binding site on the Tva receptor remains to be identified.

The principal determinants of receptor specificity in ALV are two hypervariable regions of gp85, i.e., hr1 and hr2. The subgroup A hr2 region contains several basic amino acid residues, which are found less frequently in ALV subgroups B, C, D, E, and J. These positively charged residues were shown to play a role in Tva receptor recognition, presumably by interaction with acidic residues in the LDL-A domain of Tva (42). Interestingly, although the hr1 and hr2 regions of ALV-K env do not show primary sequence similarity specifically with subgroup A, both regions in subgroup K are rich in these basic amino acids (Fig. 1). Therefore, it is plausible to speculate that ALV-K also binds to the acidic LDL-A moiety of Tva and that the specificity for Tva evolved independently from that of ALV-A. In general, we assume that amino acid residues within vr1 to vr3, hr1, and hr2 that are different between subgroups A and K but are invariant among various subgroup K strains represent the determinants of subgroup K receptor specificity.

In our host range experiments, we observed higher percentages of GFP-positive cells after infection with RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP than after infection with RCASBP(A)GFP in most galliform species and inbred chicken lines (Fig. 2B and C). Similarly, the RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP virus was less inhibited by the soluble Tva form, the immunoadhesin sTva-mIgG, than was RCASBP(A)GFP. This, in part, could also explain the aggressive pathology, which includes high mortality rates and high rates of tumors in infected birds (25, 40). On the other hand, Su et al. (31) described lower replication rates for ALV-K strains than for other ALVs, while Dong et al. (43) isolated ALV-K from clinically healthy chicken. In general, it has to be emphasized that our virus spread experiments with replication-competent RCAS vectors combine the virus entry with the efficiency of later events along the replication cycle. This experimental design simulates the natural susceptibility/resistance to the virus; however, the binding affinities of receptors and retroviral envelopes have to be examined in independent experiments in the future.

Receptor molecules for ALVs were previously identified using expression libraries that confer susceptibility to A or B subgroups (3, 7), by positional cloning based on the genetic linkage of A and C subgroup receptors (5, 44) or by coprecipitation of the J subgroup receptor with the soluble chimeric virus envelope (6). Here, we identified Tva as a K subgroup receptor while comparing the host ranges of JS11C1 virus and A subgroup ALV. This comparison might also be useful for delineation of the binding site or at least definition of the amino acid residues that are critical for receptor function, as it helped to identify W38 of chicken NHE1 as the residue discriminating species susceptible or resistant to ALV-J (17). In our screen, we found only the guinea fowl to be resistant to JS11C1, and we hope to profit from future analyses of Tva polymorphisms.

Our identification of Tva as the ALV-K receptor is also important from the point of view of antiviral management of poultry breeding. First, our results indicate that turkeys are also sensitive to ALV-K, and many wild galliform species could become natural reservoirs of the virus. The in vivo infectivity of ALV-K in nonchicken species and the potential presence of ALV-K in wild galliform populations remain to be explored. Second, as shown in Fig. 2C, several inbred lines of chickens were found to be resistant or almost resistant to RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP, corresponding to the presence of the resistant tvar allele in the CB line (16) or the tva allele with intronic deletion in the M line (20). Therefore, there are sources of genetic variability that could be used for the selection and breeding of ALV-K-resistant chickens, in contrast to the situation with ALV-J, for which no resistant allele has been found (45).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of embryo fibroblasts and cell culture.

Embryo fibroblasts of domestic chicken, ducks, and wild galliform species were prepared as described earlier (46), from embryos in the middle of incubation, i.e., 11 or 12 days posthatching. Embryonated eggs were obtained as follows: northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) and red jungle fowl (G. gallus subsp. murghi) from South Bohemia Zoological Gardens (Hluboká nad Vltavou, Czech Republic), California quail (Callipepla californica), Gambel’s quail (Callipepla gambelii), silver pheasant (Lophura nycthemera), white-crested kalij pheasant (Lophura leucomelanos subsp. hamiltoni), and gray jungle fowl (Gallus sonneratii) from the AVES Farm (Košice, Czech Republic), guinea fowl (Numida meleagris), turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), and chukar (Alectoris chukar) from the University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Science (Brno, Czech Republic), gray partridge (Perdix perdix), common ringed-neck pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), and Reeve’s pheasant (Syrmaticus reevesii) from the Židlochovice Forest Enterprise (Židlochovice, Czech Republic), and Mrs. Hume’s pheasant (Syrmaticus humiae) from Fasanerie Christian Möller (Erfurt, Germany). Chicken embryo fibroblasts were prepared from inbred lines CB, WA, L15, H6, and M and duck embryo fibroblasts from Khaki Campbell, which were maintained at the Institute of Molecular Genetics (Prague, Czech Republic). All embryo fibroblasts, as well as the permanent chicken cell line DF-1 (47) and the Japanese quail tumor cell line QT6 (48), were grown in a mixture of 2 parts Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium and 1 part F-12 medium supplemented with 8% fetal calf serum, 2% chicken serum, and 1× antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Sigma), in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C.

Construction of RCAS vector with JS11C1 env gene.

We prepared the K subgroup RCAS vector by replacing the env gene in the RCASBP(D)GFP subgroup D retrovirus vector (46, 49) with the complete env gene of JS11C1 virus. RCASBP(D)GFP transducing the GFP reporter gene was digested with KpnI and StuI (both from New England BioLabs), and the 1,853-bp fragment containing the 3′ end of pol and the entire env gene was discarded. The JS11C1 env gene (GenBank accession no. KF746200.1) was synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies) together with adjacent RCAS sequences, including the KpnI and BsaBI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends. Due to an additional BsaBI site present in the env coding sequence, a partial KpnI-BsaBI (New England BioLabs) digestion was performed to obtain the 2,120-bp fragment, which was then inserted into the RCAS backbone; the resulting vector, RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP, was used for virus propagation and infection experiments.

Construction of RCAS vectors with dsRed fluorescent marker.

The RCASBP(A)dsRed and RCASBP(JS11C1)dsRed vectors used in the superinfection experiments were prepared by replacing the gfp gene of RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP with dsRed-Monomer. The coding sequence of dsRed-Monomer, encoding a monomeric mutant of the fluorescent protein dsRed, was amplified with forward (5′-accactgtggcatcgatGGTCGCCACCATGGACAACAC-3′) and reverse (5′-ccgtacatcgcatcgatCTCTACTGGGAGCCGGAGTG-3′) primers from the pDsRed-Monomer-N1 vector (Clontech) and was cloned into ClaI-linearized RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP vectors using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech). The 17-bp overlapping sequences of the forward and reverse primers are shown as lowercase letters.

Virus propagation and FACS assay of virus infection.

All viruses used in this study were propagated by transfection of their respective vector plasmid DNA into DF-1 cells using the XtremeGENE transfection reagent (Roche). Virus stocks were harvested on day 9 or 10 posttransfection and were cleared of debris by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 10°C. Aliquoted viral stocks were stored at −80°C. Virus titers were determined by terminal dilution, subsequent infection of DF-1 cells, and detection of GFP positivity. All RCAS-based retrovirus vectors used in this study reached titers of 106 IU per ml. The in vitro infection of GFP- or dsRed-transducing RCASBP vectors was assayed in cultured avian embryo fibroblasts, QT6 cells, or NIL-2 cells. The cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well in a 24-well plate; 24 h after seeding, 5 × 105 IU of virus was added to 0.25 ml medium for 1 h. Two days postinfection, the cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, trypsinized, pelleted by centrifugation in the cultivation medium, and resuspended in Hoechst solution (Sigma). The percentages of GFP-positive cells, dsRed-positive cells, and GFP/dsRed-double-positive cells were quantitated by FACS analysis using an LSRII analyzer (Becton, Dickinson).

Ectopic expression of Tva in Syrian hamster NIL-2 cells.

Induction of susceptibility to RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP by ectopic Tva expression was shown using hamster NIL-2 cells stably transfected with the Tva expression vector (5). The NIL-2 cell line was transfected, using Lipofectamine 2000, with 2 μg of plasmid pTva together with 0.2 μg of pMC1neo poly(A) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), which contains the neomycin resistance gene. The transfected cells were grown for 10 days with G418 (500 μg/ml) to select for neomycin resistance. NIL-Tva was isolated as a cell clone from soft agar, expanded, and used for infection experiments.

Preparation of tva knockout DF-1 clone.

We employed the DF-1-tva−/− cell clone described previously (33). Briefly, we used CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing tools and cloned the guide RNA sequence 5′-CCGACTGCTACCCGCTGGAG-3′, matching the second exon of the chicken tva gene, into the single guide RNA cloning backbone of the PX458 vector (AddGene vector pSpCas9BB-2A-GFP plasmid 48138). The resulting construct was transfected into DF-1 cells using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. CRISPR/Cas9 indel activity was assayed by T7EI heteroduplex cleavage, and single-cell clones were derived using the single-cell sort mode of the Influx cell sorter (Becton, Dickinson). The expanded clone was then tested for resistance to RCASBP(A)GFP and frame-shifting deletions in the tva sequence.

Soluble Tva immunoadhesin production and inhibition of virus infection.

As a source of the soluble form of Tva receptor, we used the quail Tvas receptor fused to the constant region of a mouse IgG heavy chain, also known as immunoadhesin sTva-mIgG. The sTva immunoadhesin was expressed from the RCASBP(B)stva-mIgG vector, containing the stva-mIgG gene cassette in the ClaI cloning site (34). The RCASBP(B)stva-mIgG vector was a kind gift from M. J. Federspiel (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Stocks of sTva-mIgG immunoadhesin were generated by transfection of RCASBP(B)stva-mIgG plasmid DNA into DF-1 cells using the XtremeGENE transfection reagent (Roche) and harvesting of the supernatant after 1-week culture of infected cells. The supernatant was cleared by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −80°C. The RCASBP(A)GFP and RCASBP(JS11C1)GFP virus aliquots were mixed with sTva-mIgG supernatant at 4°C and used for DF-1 cell infection after 30 min of preincubation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by program NPU I of the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports (grant LO1419). The work of D.P. was supported in part by project 17-23675S, awarded by the Czech Science Foundation. The funders had no role in any stage of study design, data collection, or preparation of the manuscript.

We thank Zbyněk Laube (AVES Farm, Košice, Czech Republic) and Christian Möller (Fasanerie Christian Möller, Erfurt, Germany) for providing us with fertilized eggs of galliform birds used in this study. We thank Daniel Elleder for his valuable comments and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Tomáš Hron for his help with amino acid alignment of subgroup K envelopes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weiss RA. 1992. Cellular receptors and viral glycoproteins involved in retrovirus entry, p 1–108. In Levy JA. (ed), Retroviridae, vol 2 Plenum Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnard RJO, Elleder D, Young J. 2006. Avian sarcoma and leukosis virus-receptor interactions: from classical genetics to novel insights into virus-cell membrane vision. Virology 344:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates P, Young JAT, Varmus HE. 1993. A receptor for subgroup A Rous sarcoma virus is related to the low density lipoprotein receptor. Cell 74:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90726-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young JAT, Bates P, Varmus HE. 1993. Isolation of a chicken gene that confers susceptibility to infection by subgroup A avian leukosis and sarcoma viruses. J Virol 67:1811–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elleder D, Stepanets V, Melder DC, Šenigl F, Geryk J, Pajer P, Plachý J, Hejnar J, Svoboda J, Federspiel MJ. 2005. The receptor for the subgroup C avian sarcoma and leukosis viruses, Tvc, is related to mammalian butyrophilins, members of the immunoglobulin superfamily. J Virol 79:10408–10419. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10408-10419.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chai N, Bates P. 2006. Na/H exchanger type 1 is a receptor for pathogenic subgroup J avian leukosis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:5531–5536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509785103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brojatsch J, Naughton J, Rolls MM, Zingler K, Young JA. 1996. CAR1, a TNFR-related protein, is a cellular receptor for cytopathic avian leukosis-sarcoma viruses and mediates apoptosis. Cell 87:845–855. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81992-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adkins HB, Brojatsch J, Naughton J, Rolls MM, Pesola JM, Young J. 1997. Identification of a cellular receptor for subgroup E avian leukosis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:11617–11622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adkins HB, Brojatsch J, Young J. 2000. Identification and characterization of a shared TNFR-related receptor for subgroup B, D, and E avian leukosis viruses reveal cysteine residues required specifically for subgroup E viral entry. J Virol 74:3572–3578. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.8.3572-3578.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adkins HB, Blacklow SC, Young J. 2001. Two functionally distinct forms of a retroviral receptor explain the nonreciprocal receptor interference among subgroups B, D, and E avian leukosis viruses. J Virol 75:3520–3526. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3520-3526.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knauss DJ, Young JA. 2002. A fifteen-amino-acid TVB peptide serves as a minimal soluble receptor for subgroup B avian leukosis and sarcoma viruses. J Virol 76:5404–5410. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.11.5404-5410.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klucking S, Young JA. 2004. Amino acid residues Tyr-67, Asn-72, and Asp-73 of the TVB receptor are important for subgroup E avian sarcoma and leukosis virus interaction. Virology 318:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozak CA. 2011. Naturally occurring polymorphisms of the mouse gammaretrovirus receptors CAT-1 and XPR1 alter virus tropism and pathogenicity. Adv Virol 2011:975801. doi: 10.1155/2011/975801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe S, Kawamura M, Odahara Y, Anai Y, Ochi H, Nakagawa S, Endo Y, Tsujimoto H, Nishigaki K. 2013. Phylogenetic and structural diversity in the feline leukemia virus env gene. PLoS One 8:e61009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klucking S, Adkins HB, Young J. 2002. Resistance to infection by subgroups B, D, and E avian sarcoma and leukosis viruses is explained by a premature stop codon within a resistance allele of the tvb receptor gene. J Virol 76:7918–7921. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7918-7921.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elleder D, Melder DC, Trejbalova K, Svoboda J, Federspiel MJ. 2004. Two different molecular defects in the Tva receptor gene explain the resistance of two tvar lines of chickens to infection by subgroup A avian sarcoma and leukosis viruses. J Virol 78:13489–13500. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13489-13500.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kučerová D, Plachý J, Reinišová M, Šenigl F, Trejbalová K, Geryk J, Hejnar J. 2013. Nonconserved tryptophan 38 of the cell surface receptor for subgroup J avian leukosis virus discriminates sensitive from resistant avian species. J Virol 87:8399–8407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03180-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plachý J, Reinišová M, Kučerová D, Šenigl F, Stepanets V, Hron T, Trejbalová K, Elleder D, Hejnar J. 2017. Identification of New World quails susceptible to infection with avian leukosis virus subgroup J. J Virol 91:e02002-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02002-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinišová M, Šenigl F, Yin X, Plachý J, Geryk J, Elleder D, Svoboda J, Federspiel MJ, Hejnar J. 2008. A single-amino-acid substitution in the TvbS1 receptor results in decreased susceptibility to infection by avian sarcoma and leukosis virus subgroups B and D and resistance to infection by subgroup E in vitro and in vivo. J Virol 82:2097–2105. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02206-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinišová M, Plachý J, Trejbalová K, Šenigl F, Kučerová D, Geryk J, Svoboda J, Hejnar J. 2012. Intronic deletions that disrupt mRNA splicing of the tva receptor gene result in decreased susceptibility to infection by avian sarcoma and leukosis virus subgroup A. J Virol 86:2021–2030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05771-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taplitz RA, Coffin JM. 1997. Selection of an avian retrovirus mutant with extended receptor usage. J Virol 71:7814–7819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melder DC, Pankratz VS, Federspiel MJ. 2003. Evolutionary pressure of a receptor competitor selects different subgroup A avian leukosis virus escape variants with altered receptor interactions. J Virol 77:10504–10514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.19.10504-10514.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rainey GJA, Natonson A, Maxfield LF, Coffin JM. 2003. Mechanisms of avian retroviral host range extension. J Virol 77:6709–6719. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.12.6709-6719.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lounková A, Kosla J, Přikryl D, Štafl K, Kučerová D, Svoboda J. 2017. Retroviral host range extension is coupled with Env-activating mutations resulting in receptor-independent entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E5148–E5157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704750114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui N, Su S, Chen Z, Zhao X, Cui Z. 2014. Genomic sequence analysis and biological characteristics of a rescued clone of avian leukosis virus strain JS11C1, isolated from indigenous chickens. J Gen Virol 95:2512–2522. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.067264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang SW, Hsu MF, Wang CH. 2013. Gene detection, virus isolation, and sequence analysis of avian leukosis viruses in Taiwan country chickens. Avian Dis 57:172–177. doi: 10.1637/10387-092612-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwata N, Ochiai K, Hayashi K, Ohashi K, Umemura T. 2002. Avian retrovirus infection causes naturally occurring glioma: isolation and transmission of a virus from so-called fowl glioma. Avian Pathol 31:193–199. doi: 10.1080/03079450120118702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomioka Y, Ochiai K, Ohashi K, Kimura T, Umemura T. 2003. In ovo infection with an avian leukosis virus causing fowl glioma: viral distribution and pathogenesis. Avian Pathol 32:617–624. doi: 10.1080/03079450310001610640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomioka Y, Ochiai K, Ohashi K, Ono E, Toyoda T, Kimura T, Umemura T. 2004. Genome sequence analysis of the avian retrovirus causing so-called fowl glioma and the promoter activity of the long terminal repeat. J Gen Virol 85:647–652. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79778-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hatai H, Ochiai K, Nagakura K, Imanishi S, Ochi A, Kozakura R, Ono M, Goryo M, Ohashi K, Umemura T. 2008. A recombinant avian leukosis virus associated with fowl glioma in layer chickens in Japan. Avian Pathol 37:127–137. doi: 10.1080/03079450801898815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su Q, Li Y, Li W, Cui S, Tian S, Cui Z, Zhao P, Chang S. 2018. Molecular characteristics of avian leukosis viruses isolated from indigenous chicken breeds in China. Poult Sci 97:2917–2925. doi: 10.3382/ps/pex367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nehyba J, Svoboda J, Karakoz I, Geryk J, Hejnar J. 1990. Ducks: a new experimental host system for studying persistent infection with avian leukaemia retroviruses. J Gen Virol 71:1937–1945. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-9-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koslová A, Kučerová D, Reinišová M, Geryk J, Trefil P, Hejnar J. 2018. Genetic resistance to avian leukosis viruses induced by CRISPR/Cas9 editing of specific receptor genes in chicken cells. Viruses 10:605. doi: 10.3390/v10110605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmen SL, Salter DW, Payne WS, Dodgson JB, Hughes SH, Federspiel MJ. 1999. Soluble forms of the subgroup A avian leukosis virus [ALV(A)] receptor Tva significantly inhibit ALV(A) infection in vitro and in vivo. J Virol 73:10051–10060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmen SL, Melder DC, Federspiel MJ. 2001. Identification of key residues in subgroup A avian leukosis virus envelope determining receptor binding affinity and infectivity of cells expressing chicken or quail Tva receptor. J Virol 75:726–737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.726-737.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lavillette D, Marin M, Ruggieri A, Mallet F, Cosset FL, Kabat D. 2002. The envelope glycoprotein of human endogenous retrovirus type W uses a divergent family of amino acid transporters/cell surface receptors. J Virol 76:6442–6452. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.13.6442-6452.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshikawa R, Yasuda J, Kobayashi T, Miyazawa T. 2012. Canine ASCT1 and ASCT2 are functional receptors for RD-114 virus in dogs. J Gen Virol 93:603–607. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.036228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malicorne S, Vernochet C, Cornelis G, Mulot B, Delsuc F, Heidmann O, Heidmann T, Dupressoir A. 2016. Genome-wide screening of retroviral envelope genes in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus, Xenarthra) reveals an unfixed chimeric endogenous betaretrovirus using the ASCT2 receptor. J Virol 90:8132–8149. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00483-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sommerfelt MA, Weiss RA. 1990. Receptor interference groups of 20 retroviruses plating on human cells. Virology 176:58–69. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90230-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, Lin W, Chang S, Zhao P, Zhang X, Liu Y, Chen W, Li B, Shu D, Zhang H, Chen F, Xie Q. 2016. Isolation, identification and evolution analysis of a novel subgroup of avian leukosis virus isolated from a local Chinese yellow broiler in South China. Arch Virol 161:2717–2725. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2965-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mingzhang R, Zijun Z, Lixia Y, Jian C, Min F, Jie Z, Ming L, Weisheng C. 2018. The construction and application of a cell line resistant to novel subgroup avian leukosis virus (ALV-K) infection. Arch Virol 163:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3563-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rong L, Edinger A, Bates P. 1997. Role of basic residues in the subgroup-determining region of the subgroup A avian sarcoma and leukosis virus envelope in receptor binding and infection. J Virol 71:3458–3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong X, Zhao P, Xu B, Fan J, Meng F, Sun P, Ju S, Li Y, Chang S, Shi W, Cui Z. 2015. Avian leukosis virus in indigenous chicken breeds, China. Emerg Microbes Infect 4:e76. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elleder D, Plachý J, Hejnar J, Geryk J, Svoboda J. 2004. Close linkage of genes encoding receptors for subgroups A and C of avian sarcoma/leucosis virus on chicken chromosome 28. Anim Genet 35:176–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2004.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reinišová M, Plachý J, Kučerová D, Šenigl F, Vinkler M, Hejnar J. 2016. Genetic diversity of NHE1, receptor for subgroup J avian leukosis virus, in domestic chicken and wild anseriform species. PLoS One 11:e0150589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Federspiel MJ, Hughes SH. 1997. Retroviral gene delivery. Methods Cell Biol 52:179–214. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)60379-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Himly M, Foster DN, Bottoli I, Iacovoni JS, Vogt PK. 1998. The DF-1 chicken fibroblast cell line: transformation induced by diverse oncogenes and cell death resulting from infection by avian leukosis viruses. Virology 248:295–304. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moscovici C, Moscovici MG, Jimenez H, Lai MM, Hayman MJ, Vogt PK. 1977. Continuous tissue culture cell lines derived from chemically induced tumors of Japanese quail. Cell 11:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hughes SH. 2004. The RCAS vector system. Folia Biol (Praha) 50:107–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]