Abstract

Objectives

Continuous formative assessment with appropriate feedback is the pillar of effective clinical teaching and learning. Group Objective Structured Clinical Examination (GOSCE) has been reported as a resource-effective method of formative assessment. The present study aims to describe the development and evaluation of GOSCE as a formative assessment for pre-clerkship medical students.

Methods

At the University of Sharjah, GOSCE was introduced to medical students in Years 1, 2, and 3. The GOSCE was conducted as a formative assessment in which groups of 4–5 students were observed while they performed various clinical skills, followed by structured feedback from clinical tutors and peers. GOSCE was evaluated both quantitatively and qualitatively and appropriate statistical analysis was applied to evaluate their responses.

Results

A total of 232 students who attended the GOSCE responded to the questionnaires. Most of the students and clinical tutors preferred formative GOSCE over individual feedback. Both students and clinical tutors valued the experience as it helped students to identify gaps and to share knowledge and skills among group members.

Conclusion

This study found that formative GOSCE provided a valuable and feasible educational opportunity for students to receive feedback about their clinical skills.

Keywords: Clinical skills, Feedback, OSCE, Peer, Small group

الملخص

أهداف البحث

التقييم التكويني المستمر مع التغذية الراجعة المناسبة هو الدعامة للتعليم والتعلم السريري الفعال. وقد تم تسجيل الامتحانات السريرية الجماعية المبنية على الموضوعية كطريقة فاعلة من حيث الموارد للتقييم التكويني. تهدف الدراسة الحالية إلى وصف استحداث وتقييم الامتحانات السريرية الجماعية المبنية على الموضوعية كتقييم تكويني لطلاب الطب في مرحلة ما قبل التدريب.

طرق البحث

تم تطبيق الامتحانات السريرية الجماعية المبنية على الموضوعية على طلبة السنوات الأولى والثانية والثالثة من كلية الطب في جامعة الشارقة. وقد أُجريت الامتحانات السريرية الجماعية المبنية على الموضوعية كتقييم تكويني لملاحظة مجموعات من طلبة السنوات الرابعة والخامسة أثناء أدائهم لبعض المهارات السريرية المختلفة، متبوعة بتغذية راجعة منظمة من قِبل المعلمين السريريين والأقران. وقد تم تقييم الامتحانات السريرية الجماعية المبنية على الموضوعية كما ونوعا، وتم تطبيق التحاليل الإحصائية المناسبة لتقييم إجاباتهم.

النتائج

أجاب ما مجموعه ٢٣٢ طالبا من الذين حضروا الامتحانات السريرية الجماعية المبنية على الموضوعية، على الاستبانات. وفضّل أغلب الطلبة والمعلمون السريريون الامتحانات السريرية الجماعية المبنية على الموضوعية التكوينية مقارنة بالتغذية الراجعة الفردية. وقد أشاد كل من الطلبة والمعلمون السريريون بالامتحانات السريرية الجماعية المبنية على الموضوعية، كونها ساعدت الطلبة على تحديد الفجوات وتبادل المعرفة والمهارات بين أعضاء المجموعة.

الاستنتاجات

وجدت هذه الدراسة أن الامتحانات السريرية الجماعية المبنية على الموضوعية التكوينية وفرت فرصة تعليمية قيّمة وقابلة للتطبيق، لتوفير التغذية الراجعة للطلبة حول مهاراتهم السريرية.

الكلمات المفتاحية: المهارات السريرية, التغذية الراجعة, الامتحانات السريرية المبنية على الموضوعية, الأقران, مجموعة صغيرة

Introduction

Feedback is a pillar of effective clinical teaching and learning. It aims to reinforce good practice, correct poor performance and identify the path to clinical improvement.1, 2, 3 Studies have shown that feedback during clinical training improves interviewing and communication skills, physical examination skills, procedural skills, problem-based learning, team building, and personal and professional behaviours.4 Incorporating activities that will foster a culture of effective feedback as part of learning and teaching is a necessity.5

Formative Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) has been used to provide feedback to students on their clinical skills,1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 aiming to enhance learners’ behaviour and help students to recognize their weaknesses.14, 15, 16 However, OSCE is resource-consuming in terms of personnel, facilities, finances, and time.17

The Group Objective Structured Clinical Examination (GOSCE) is a variation of the traditional OSCE format which has been reported in a few studies in the medical education literature.18 In GOSCE, learners are assigned to groups rather than individually as they rotate around the OSCE stations.19, 20, 21 GOSCE provides a chance for the learners to observe each other performing the clinical task at each station, and more importantly practice self-assessment and receive feedback.18 The format of the GOSCE has the added benefit of being resource-effective for assessing clinical skills, requiring fewer facilities per learner than the conventional formative OSCE.18 In this study we aim to describe the development and evaluation of GOSCE in delivering feedback to pre-clerkship medical students.

Materials and Methods

Context

This is a descriptive study illustrating our experience in conducting formative GOSCE for medical students in Years 1–3 as part of the clinical skill (CS) training program during the academic year 2016–2017. The medical program is a six-year program in three phases: The Foundation year, Preclinical phase (Years 1, 2, and 3), and Clinical phase (Years 4 and 5). There were around 122 students in Year 1, 118 students in Year 2, and 104 students in Year 3 during the academic year 2016–2017.

The CS training program is designed to train, assist, and guide students as they acquire the professional skills and core competencies that all physicians must have to practice medicine. The program starts in the first week of the medical course in Year 1 in parallel with other basic medical sciences. During the first 3 years, students in the Pre-Clerkship phase of the curriculum learn and apply clinical skills, including communication skills and history taking, physical examination, clinical reasoning, decision-making skills, ethics, and writing skills as well as procedural skills. The teaching and learning take place in a simulated environment in four well-equipped CS labs and is facilitated by trained clinical tutors. Monitoring students' progress is fundamental to the CS acquisition program. Clinical tutors provide students with continuous constructive formal and informal feedback during every training session. However, formative OSCEs consist of structured feedback sessions conducted twice each semester.

Initially, the CS team adopted traditional formative OSCE, where each student was exposed to only one station chosen at random according to the requirements for the semester. The student was requested to perform one clinical task in 10–15 min, depending on the clinical task examined, while being observed by the clinical tutor, who provided feedback on the student's performance. Each formative OSCE lasts about four hours for the whole batch of about 100 students in each year. However, due to the deficiencies of clinical tutors and the increasing number of students, the clinical skill team felt the need to develop and implement formative group OSCE, in which students would be exposed to more than one station and receive feedback from their peers.

GOSCE design

A blueprint for each GOSCE is prepared according to the clinical curriculum and all stations are mapped according to each clinical competency. The GOSCE stations consist of different clinical tasks that match the clinical curriculum. The stations used during the GOSCE assess history taking, explanation, physical examination, procedures, and data interpretation skills, as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Academic year and related clinical skills for the formative GOSCE.

| Academic year 2016–2017/semester | Clinical skill performed during the formative OSCE |

|---|---|

| Year 1/Semester 1 | Station 1: History taking and explanation skills Station 2: BP measurement and IM injections |

| Year 2/Semester 3 | Station 1: 2 History taking (Cardiovascular + Respiratory) Station 2: 2 Explanation (Meter dose inhaler + Chest x-ray) Station 3: 2 Examination (Cardiovascular + BP measurement) Station 4: 2 Examination (Respiratory + Thyroid) |

| Year 3/Semester 5 | Station 1: (Neurological examination, Otoscopy, Neurological history taking) Station 2: (Cranial nerve examination, Ophthalmoscopy, Neurological history taking) |

All requirements needed for each GOSCE station are prepared and reviewed in advance by the clinical skill team. These include students' instructions, checklists to assess students' performance, other equipment needed for each station such as stethoscopes, sphygmomanometers, measuring tapes, etc., and trained simulated patients.

Layout of the GOSCE

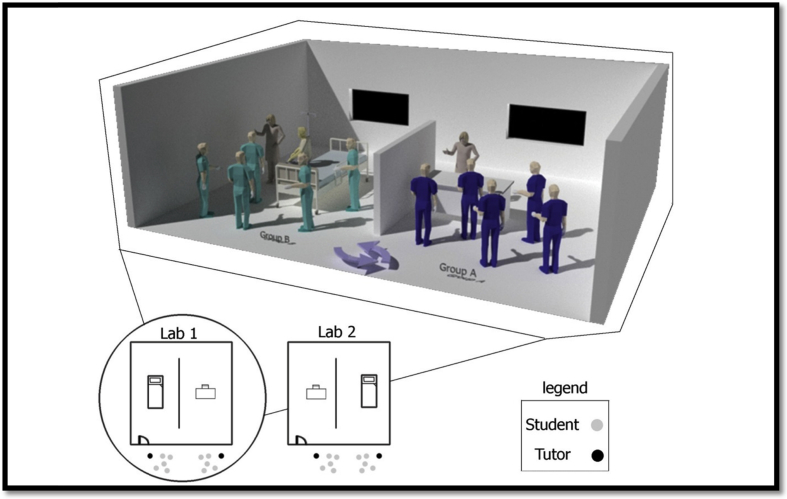

Before the GOSCE, an announcement is sent to the students informing them to prepare and practice their skills. Clinical tutors review the stations and have a standardization session during which they agree on how to conduct the GOSCE and how to evaluate students and give feedback. On the day of the GOSCE, students are briefed on how GOSCE is conducted and what to expect after completing it. Students are then sub-divided into groups of four to five and allocated to the stations. The first student is examined on the assigned task while being observed by the other students and the clinical tutor, as portrayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Virtual depiction of the GOSCE setting.

The total time allotted for each group/station was 12 min: 7 min for the student to perform the task and 5 min for feedback. The feedback is structured to allow for self and peer assessment. The clinical tutor first asks the student to comment on his/her own performance, then his or her peers are asked if they have suggestions for improvement. Finally, the clinical tutor provides feedback. The students then take turns performing the assigned tasks as they move around the stations. After completing the formative OSCE, students evaluate the GOSCE by filling out a paper-based questionnaire to record their opinions. The questionnaire was developed and reviewed by several members of the clinical skill team and head of the clinical skill program, then tested in a pilot study.

Data collection

The questionnaire comprised of seven questions exploring students' opinion on the GOSCE; five questions are scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. One question asks students whether they prefer to receive feedback on their performance in a small group or individually (alone). This was followed by an open-ended question for students to express why they prefer formative OSCE in a group or as individual feedback (the questionnaire is included as Appendix 1). Clinical tutors were asked to provide their feedback on the GOSCE by providing responses to three open-ended questions, which were sent to all clinical tutors by email (the questionnaire is included as Appendix 2).

Data analysis

A chi-square goodness-of-fit test was used to examine whether medical students prefer formative Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in groups or individually and to compare it with a didactic clinical skills revision session and determine what type of feedback they prefer. Analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 (IBM Corp, New York, USA).

Qualitative data extracted from students' answers to the open-ended questions were entered into an Excel sheet to assist in quantifying the data. Through an iterative process of reading, coding, and categorization, authors S.S. and M.D. independently analysed the data from students answers to the open-ended questions, while authors N.A. and S.S. independently analysed the data from clinical tutors. Final categories were reviewed and agreed on by all authors.

Results

Students' quantitative data analysis

Of the 232 students recruited to the study, 114 (49.1%) were from Year 1, 64 (27.6%) from Year 2, and 54 (23.3%) from Year 3. More than two-thirds of the respondents were female (69.2%). A majority of the students preferred formative OSCE over a didactic clinical skills revision session, 108 (94.7%) from Year 1, 56 (87.5%) from Year 2, and 44 (81.5%) from Year 3, with no significant difference between the years, χ2(4, N = 232) = 8.441, p = .077. A majority of students in all three years thought that the feedback they received was informative. Most of the students preferred small group feedback over individual feedback, 104 (91.2%) from Year 1, 55 (85.9%) from Year 2, and 49 (90.7%) from Year 3, χ2(4, N = 232) = 3.490, p = .515. Year 1 and Year 3 students considered the timing of each station adequate; however, only 60.9% of Year 2 students thought so, compared to 93% from Year 1 and 98% from Year 3, χ2(4, N = 232) = 45.445, p < .0001. We did not find any statistical differences between men and women in our sample on any of the surveyed items.

Students' qualitative data analysis

A total of 123 student expressed their reasons for preferring formative OSCE in a group or individually. Some of the students' unedited comments are shown in Table 2, Table 3 in italics. Most students, who preferred formative OSCE, appreciated the feedback received from their peers. Students mentioned that the experience helped them identify their gaps; a few commented that they appreciated the sharing of knowledge. One student mentioned being less nervous in a small group.

Table 2.

Content analysis of students' responses to open-ended questions for preferring GOSCE.

| Categories | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Total | Students' comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning from peers | 26 | 14 | 9 | 49 |

‘peers can add to my knowledge’ ‘to note others’ mistakes and learn from them’ ‘I will remember better’ |

| Feedback | 50 | 8 | 10 | 68 |

‘to get more feedback’ ‘several pieces of feedback from various parties could be obtained in this way, making it more beneficial in the future.’ ‘sometimes a colleague may mention something useful and it helps to know others’ mistakes' |

| Identify gaps | 4 | 0 | 4 | ‘having more than one observer gives me a better chance to see my weak points’ | |

| Less nervous | 1 | 1 | ‘helps me be less nervous’ | ||

| Confident | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ‘it makes me more confident’ |

| 81 | 22 | 20 | 123 |

Table 3.

Content analysis of students' response to open-ended questions for preferring individual OSCE.

| Categories | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Total | Students' comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-assessment | 0 | 1 | 1 | ‘better for assessing myself’ | |

| More comfortable | 0 | 1 | 1 | ‘I'll be more comfortable as I'll be alone with the examiner’ | |

| More practice | 1 | 1 | 2 | ‘we will have to practice more’ | |

| More interaction | 0 | 1 | 2 | ‘more questions to ask; more interaction’ | |

| Avoid embarrassment | 1 | 1 | 2 | ‘to avoid embarrassment and feel calmer’ | |

| Similar to exam | 0 | 1 | 2 | ‘close to the environment of the exam’ | |

| More feedback | 0 | 1 | 1 | ‘I will be more involved in the feedback’ | |

| Focus | 1 | 1 | ‘focus on my overall performance’ | ||

| Tutor feedback | 1 | 1 | ‘tutor could tell me more information’ | ||

| Avoid distraction | 1 | 1 | ‘to avoid distractions and laughter in the group’ | ||

| More confident | 1 | 1 | ‘I will be more confident if I am alone and I will not be stressed’ | ||

| Identify gap | 1 | 1 | ‘I get to know my weak points and what needs improvement; to do well on the OSCE; to get all the wrong points and try to correct them’ | ||

| 7 | 3 | 4 | 14 |

The reasons of 14 students from Years 1, 2, and 3 who preferred individual formative OSCE included: better self-assessment, a more comfortable feeling and greater confidence when alone, more practice, more interaction, avoidance of embarrassment, similarity to an exam set up, better focus and avoidance of distraction, more tutor feedback, and better identification of their gaps.

Clinical tutors' qualitative data analysis

Most of the clinical tutors were satisfied with the organization, timing, and setup of the Formative OSCE. They preferred Formative OSCE in small groups for different reasons. One reason was the learning opportunity provided, which was noted by most tutors. Another reason noted was greater resource effectiveness, as per the comment of one clinical tutor. Selected tutor comments are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Content analysis of clinical tutors' comments regarding GOSCE.

| Area of feedback | Notes |

|---|---|

| 1. Learning Opportunities | L.E. ‘I think that the feedback will be more informative for the students and will be from different points of view because it will reflect the self and peer evaluations in addition to the tutor's feedback’ L.E. ‘Most of the students feel more supported by their colleagues and the experience is more enjoyable’ M.D. ‘Because they are in small groups, students will be able to learn more, not only from their own mistakes but also from their colleagues’ mistakes' N.H. ‘Gives students the chance to practice’ A.H. ‘More interactive’ |

| 2. Resource Effectiveness | L.E. ‘A shorter time was taken by the groups. The time taken to finish the evaluation and give feedback will be less than the time consumed in an individual formative OSCE, in addition to the tasks that will be covered by each student either observing or doing the skills by himself’ |

| 3. Disadvantages of Formative OSCE in Groups | L.E. ‘A few students may feel uncomfortable being evaluated in front of others and not all skills may be performed by a given student’ M.D. ‘For some of the students it's considered embarrassing’ A.H. ‘Not all students have the same chance to practice the full skill’ N.H. ‘Some students will not consider it a real exam so they will not be prepared’ |

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of providing feedback to individual medical students in small groups during the first three years of the (pre-clerkship phase) curriculum. Feedback is a fundamental core component of the clinical skills program in our college. The feedback, which starts early in the first week of the program, aims to reinforce good practice, identify gaps, correct poor performance, and suggest modes for improvement. However, it is well known that teachers, unlike students, believe that they give adequate and regular feedback.1, 2, 3

We have demonstrated that students appreciate the feedback given to them by the clinical tutors on various clinical skills, including communication and history taking, physical examination, procedural skills, patient safety, and professionalism. This is similar to the findings of other studies of feedback.4, 20, 22 A majority of our students preferred to receive feedback in small groups during the formative GOSCE. The reasons given included the chance to receive multiple feedback from peers and tutors on individual performance as well as the benefit of observing the performance of peers and providing feedback to them. Students mentioned that their peers can add to their knowledge by noting their mistakes and that GOSCE helps them remember the feedback given by peers better than individual feedback during the traditional OSCE does. The results are similar to those of a previous study20 that reported a 2.5-hr communication skills GOSCE session to be an efficient learner-centred method for clerkship students to give feedback and to apply self-assessment in a formative setting. Moreover, students also realized that a 2.5-hr communication skills GOSCE improved their level of confidence in communicating with patients.20 In our study, we did not assess our students' perceived confidence before and after the GOSCE; however, we would expect the GOSCE to positively impact our students' confidence in performing various clinical skills, including their communication skills.

It is to be expected that well-prepared students would be confident in performing the skills individually and in groups, unlike weaker and less-prepared students, who would be more confident during individual sessions than in groups.

Most of the students' feedback on GOSCE was echoed by that of the clinical tutors, who reported that the majority of students preferred GOSCE and valued learning from their reflections on action as well as reflections in action. The peer feedback provided an extra dimension and value for each student which is lacking in individual OSCE. The tutors' overall specific and comprehensive feedback is provided in both OSCE and GOSCE; however, during GOSCE the tutor provides individual as well as collective feedback on the performance of the group. Furthermore, during GOSCE, the exchange of the groups of students between clinical tutors when rotating from one station to another provided the added value of exposing the students to other aspects of their performance that might be overlooked by the first tutor.

The clinical tutors provided their insights into other advantages of the GOSCE. In general, while the logistics of conducting GOSCE and OSCE are similar, the overall time spent is less and there are fewer tutors/examiners in GOSCE than OSCE, making it more feasible for the pre-clinical years as well as for clinical clerkships.20, 23 The clinical tutors also commented that the peers provided support to each other and their time was more enjoyable during GOSCE. Additional skills learned included teamwork22 and the ability to provide feedback.20

However, in our study, not all students preferred GOSCE. A small proportion of students (about 10% of Year 1 and Year 2 students and 14% of Year 3 students) preferred to receive feedback individually. Reasons given included that they avoided embarrassment and had a more relaxed feeling, they received more time and focus for the individual student, and there were more questions to ask, as well as the view that individual stations reflected a real summative OSCE. Another factor is that in our GOSCE not all students participated in all tasks, as they did in OSCE.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. First, we did not investigate the relation between formative GOSCE and summative grades, and second, our study focused only on the pre-clerkship phase. We would have liked to have included the simulated patients' feedback as well, but that was not feasible in our organization.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that students and tutors viewed GOSCE favourably because it provides the opportunity for each student to observe and reflect on his or her own performance and to receive feedback from his or her peers as well as from the tutor. The logistics of GOSCE is more efficient than OSCE in terms of requiring less time and fewer examiners. Moreover, in GOSCE, peers provide a supportive as well as enjoyable learning environment.

Recommendation

The study advocates using GOSCE because it can provide feedback regarding clinical competencies at various stages of the curriculum. Furthermore, using GOSCE on a broader scale can improve academic competencies. Moreover, GOSCE could offer a solution to the problem of limited resources in terms of tutors and time. Hence, future research can focus on utilizing peers to provide a structured formative assessment.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors' contributions

NDS and AMA initiated the research idea and formulated the research topic and SIS, NYA, MTD and IEM contributed to the qualitative and quantitative data analysis. All authors equally contributed to writing and critically reviewing the final manuscript. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the valuable contributions of all the tutors and facilitators, Dr. Ahmed Hasswan, Dr. Ahmed Ahmed Khalafalla, Dr. Firdaws Fernini, Dr. Elnaz Ghasemi, Dr. Heba Walid, Dr. Lemya Eltayb, Dr. Majd Ahmad, Dr. Mona Dagani, Dr. Nour Hisham and Dr. Rania Adil Elhussain for helping to coordinate the GOSCE and sharing their valuable feedback regarding GOSCE assessment.

The authors express their gratitude to all the students in the College of Medicine of the University of Sharjah who participated with their valued comments.

The authors are also thankful to Architect Mohamed Nasereldeen Elkhateeb for designing Figure 1 using Sketch Up 3D modelling software and Adobe Photoshop.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2018.06.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Aeder L., Altshuler L., Kachur E., Barrett S., Hilfer A., Koepfer S. The “Culture OSCE”-introducing a formative assessment into a postgraduate program. Educ Health. 2007;20(1):11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagri A.S., Zaw K.M., Milanez M.N., Palacios J.C., Qadri S.S., Bliss L.A. Geriatric medicine fellows' experiences and attitudes toward an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) Educ Gerontol. 2009;35(4):283–295. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett V., Furmedge D. The hidden value of a mock OSCE. Clin Teach. 2013;10(6):407–408. doi: 10.1111/tct.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deane R.P., Joyce P., Murphy D.J. Team Objective Structured Bedside Assessment (TOSBA) as formative assessment in undergraduate obstetrics and gynaecology: a cohort study. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):172. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0456-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett R.E. Formative assessment: a critical review. Assessment in education: principles. Policy Pract. 2011;18(1):5–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brazeau C., Boyd L., Crosson J. Changing an existing OSCE to a teaching tool: the making of a teaching OSCE. Acad Med. 2002;77(9):932. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200209000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browne G., Bjelogrlic P., Issberner J., Jackson C. Undergraduate student assessors in a formative OSCE station. Med Teach. 2013;35(2):170–171. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.737060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandra P.S., Chaturvedi S.K., Desai G. Objective standardized clinical assessment with feedback: adapting the objective structured clinical examination for postgraduate psychiatry training in India. Indian J Med Sci. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta P., Dewan P., Singh T. Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) revisited. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47(11):911–920. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison C.J., Molyneux A.J., Blackwell S., Wass V.J. How we give personalised audio feedback after summative OSCEs. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):323–326. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.932901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khattab A.D., Rawlings B. Use of a modified OSCE to assess nurse practitioner students. Br J Nurs. 2008;17(12) doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.12.30293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen T., Jeppe-Jensen D. The introduction and perception of an OSCE with an element of self-and peer-assessment. Eur J Dent Educ. 2008;12(1):2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lele S.M. A mini-OSCE for formative assessment of diagnostic and radiographic skills at a dental college in India. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(12):1583–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alsenany S., Al Saif A. Developing skills in managing Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE) Life Sci J. 2012;9(3):597–602. [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'sullivan P., Chao S., Russell M., Levine S., Fabiny A. Development and implementation of an objective structured clinical examination to provide formative feedback on communication and interpersonal skills in geriatric training. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(9):1730–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patrício M.F., Julião M., Fareleira F., Carneiro A.V. Is the OSCE a feasible tool to assess competencies in undergraduate medical education? Med Teach. 2013;35(6):503–514. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.774330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner J.L., Dankoski M.E. Objective structured clinical exams: a critical review. Fam Med. 2008;40(8):574–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biran L. Self-assessment and learning through GOSCE (group objective structured clinical examination) Med Educ. 1991;25(6):475–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1991.tb00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliot D.L., Fields S.A., Keenen T.L., Jaffe A.C., Toffler W.L. Use of a group objective structured clinical examination with first-year medical students. Acad Med. 1994;69(12):990–992. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199412000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konopasek L., Kelly K.V., Bylund C.L., Wenderoth S., Storey-Johnson C. The group objective structured clinical experience: building communication skills in the clinical reasoning context. Patient Educ Counsel. 2014;96(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meagher F.M., Butler M.W., Miller S.D., Costello R.W., Conroy R.M., McElvaney N.G. Predictive validity of measurements of clinical competence using the Team Objective Structured Bedside Assessment (TOSBA): assessing the clinical competence of final year medical students. Med Teach. 2009;31(11):e545–e550. doi: 10.3109/01421590903095494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Symonds I., Cullen L., Fraser D. Evaluation of a formative interprofessional team objective structured clinical examination (ITOSCE): a method of shared learning in maternity education. Med Teach. 2003;25(1):38–41. doi: 10.1080/0142159021000061404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singleton A., Smith F., Harris T., Ross-Harper R., Hilton S. An evaluation of the team objective structured clinical examination (TOSCE) Med Educ. 1999;33(1):34–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.