Abstract

Objectives

Food craving is a well-known phenomenon during pregnancy that is driven by nutritional requirements for optimal foetal development. This mechanism plays a vital role in ensuring normal prenatal and postnatal development. The goal of the present study is to assess whether cravings experienced during pregnancy are related to children's behaviour.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted in the gynaecology outpatient unit of a local hospital on healthy non-pregnant women, with children aged between 18 months and 5 years. Eligible women completed a questionnaire regarding their child's behaviours and cravings experienced during their pregnancy. Chi-square tests were used to examine relationships between cravings and behaviour.

Results

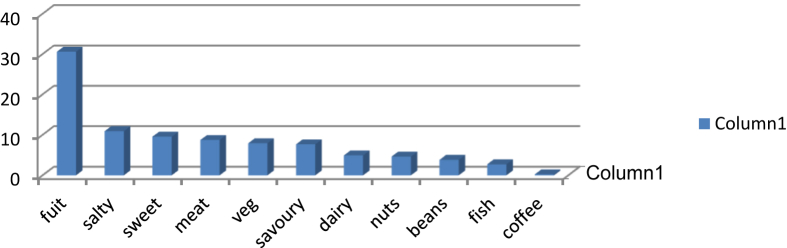

A total of 336 women were included in the study (child mean age = 44.11 ± 15.65 months; 55.7% females). Food cravings were experienced by 83.1% (n = 304/366) of the participants. The most commonly reported food craving was for fruit (n = 112, 33.3%). Other cravings included salty crackers (n = 40, 10.9%), sweets (n = 35, 9.6%), meat (n = 32, 8.7%), and vegetables (n = 29, 7.9%). There was variation in frequency of the children's behavioural problems: always (more than 50% of the occasions), sometimes (10–50% of the occasions), and none.

Conclusions

Our analyses showed that most behavioural issues were not associated with cravings during pregnancy. Further investigation into how diet and foetal development may impact childhood behaviour is warranted.

Keywords: Child behaviour, Diet, Foetal development, Food cravings, Pregnancy

الملخص

أهداف البحث

الشغف للطعام هو ظاهرة معروفة أثناء الحمل وذلك بسبب المتطلبات الغذائية للنمو الأمثل للجنين. هذه الآلية تلعب دورا حيويا في ضمان التطور الطبيعي قبل وبعد الولادة. تهدف هذه الدراسة لتقييم ما إذا كان شغف الطعام يرتبط بسلوك الطفل.

طرق البحث

أجريت دراسة استرجاعية في وحدة العيادات الخارجية النسائية في مستشفى محلي على سيدات أصحاء غير- حوامل، لديهن أطفال أعمارهم بين ١٨ شهرا إلى ٥ سنوات. وأكملت السيدات المؤهلات استبانة بخصوص سلوكيات أطفالهن وخبرتهن في الرغبة الشديدة للطعام خلال حملهن. استخدمت اختبارات مربع- كاي لاختبار العلاقة بين الرغبة الشديدة للطعام والسلوك.

النتائج

تم إشراك ٣٣٦ سيدة في هذه الدراسة (معدل عمر الأطفال = ٤٤.١١ ± ١٥.٦٥ شهرا؛ ٥٥.٧٪ إناث). مرَّ بتجربة الرغبة الشديدة للطعام ٨٣.١٪ (عدد = ٣٦٦⁄٣٠٤) من المشتركات. كانت الفواكه هي الأكثر شيوعا من الأطعمة المرغوبة (عدد =١١٢؛ ٣٣.٣٪). وتضمنت الرغبات الشديدة الأخرى البسكويتات المالحة (عدد= ٤٠؛ ١٠.٩٪)، والحلويات (عدد =٣٥؛ ٩.٦٪)، واللحوم (عدد =٣٢؛ ٨.٧٪) والخضروات (عدد= ٢٩؛ ٧.٩٪). كما كان هناك قضايا سلوكية مختلفة للأطفال: دائما (أكثر من ٥٠٪ من الأوقات)، بعض الأحيان (١٠-٥٠٪ من الأوقات)، ولا شيء.

الاستنتاجات

أظهرت تحليلاتنا أن معظم المشكلات السلوكية لم ترتبط بشغف الطعام أثناء الحمل. يحتاج الأطباء إلى استكشاف الإتجاهات المستقبلية من حيث كيفية تأثير الغذاء ونمو الجنين على القضايا السلوكية لدى الأطفال.

الكلمات المفتاحية: سلوك الطفل, الحمل؛ شغف الطعام, نمو الطفل, غذاء

Introduction

Food craving is a common occurrence during pregnancy. This phenomenon, also referred to as ‘selective hunger’, is an intense desire to consume a specific food or particular nutrients (which is different from what is experienced during normal hunger). For centuries, the desire for specific foods during pregnancy has been documented, with 50–90% of women reporting some sort of craving.1

Cravings most commonly develop towards the end of the first trimester, with a peak during the second trimester, and a subsequent decline following delivery.2 Common cravings include sweets, dairy, fruit, vegetables, and fast food.3 Cravings for salty and savoury food are less commonly reported.4 In a study by Orloff,5 all participants sampled had experienced at least one craving, with cravings for ‘sweets’ and ‘fast food’ being most common.

Various hypotheses regarding why pregnant women experience a high frequency of cravings have been put forward. Hormones have been postulated to play a key role. Pregnancy is associated with large hormonal fluctuations, as the body prepares to support a growing foetus. Neuropeptide Y, a hormone associated with appetite stimulation in both humans and animals, increases during pregnancy.6 Other hormones, such as leptin and ghrelin, are also associated with appetite changes in animal models, although there is no strong data to date linking these hormones to appetite changes in humans. An alternative theory is that food cravings are driven by nutritional deficiencies in the mother and/or nutritional requirements for optimal foetal development, suggesting that responding to such cravings may play an important role in ensuring normal prenatal development. Such nutritional requirements include B vitamins, folate, iron, and magnesium.7, 8 However, studies have also observed that cravings vary enormously across cultures, with women in different countries craving foods that are culturally and regionally available.9 Given that food cravings may be associated with certain nutritional deficiencies, which may impact foetal development, it is possible that cravings and acquired nutrition during pregnancy may impact later development (i.e. child behavioural issues).

Despite food cravings being a well-recognised part of pregnancy, there is a paucity of research on how nutritional factors during pregnancy impact later health and development of both the mother and the child. Thus, we were interested in examining whether the presence of cravings during pregnancy is associated with challenging behaviours exhibited by children during infancy and toddlerhood. Behavioural problems are common in early childhood and can result in enduring costs to the individual and society (e.g. an increased risk for mental and physical illness, criminality, educational failure, and drug and alcohol misuse). Here, we define behavioural issues as the symptomatic expression of emotional or interpersonal maladjustment (including nail biting, enuresis, negativism, and/or overt hostile and antisocial acts). We selected the 40 most common behavioural maladjustment profiles for the present study.

Materials and Methods

Participants and data extraction

A retrospective study was conducted, which included healthy non-pregnant women visiting a gynaecology outpatient unit at a university hospital (tertiary and referral centre) from January 2014 to January 2015. Women were included in the study if they had a child aged 18 months to 5 years, were in good health condition with no history of any medical disorders, and were willing to participate. The study was conducted with the approval of the Jordan University of Science and Technology's ethics committee.

All participants provided informed consent and completed the questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed by university staff within the paediatric, psychiatry, and behavioural science units. Study parameters are shown in Table 1, Table 2. We cross-validated the questionnaire in Arabic and English. A trained researcher interviewed all participants. The questionnaire comprised 40 questions on the child's current behaviours, cravings experienced during pregnancy, whether the baby was delivered at term, the type of delivery (normal/caesarean), and whether iron treatment or vitamins were used during pregnancy.

Table 1.

Food cravings experienced during pregnancy.

| Food | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Fruit | 112 (30.60) |

| Salty crackers | 40 (10.93) |

| Sweets | 35 (9.56) |

| Meat | 32 (8.74) |

| Vegetables | 29 (7.92) |

| Savoury food | 28 (7.65) |

| Dairy | 18 (4.92) |

| Nuts | 17 (4.64) |

| Beans | 14 (3.83) |

| Fish | 10 (2.73) |

| Coffee | 1 (0.27) |

Table 2.

Frequency of child behavioural problems.

| Behaviour | n | Never | Sometimes | Always | Behaviour | n | Always | Sometimes | Never |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acts younger than age | 366 | 340 (92.9) | 21 (5.7) | 5 (1.4) | Gets frustrated easily | 364 | 296 (80.9) | 53 (14.5) | 15 (4.1) |

| Does not socialise well with other children | 365 | 315 (86.1) | 41 (1) | 9 (2) | Jealous | 363 | 131 (35.8) | 79 (21.6) | 153 (41.8) |

| Acts like a young adult | 364 | 340 (92.9) | 15 (4.1) | 9 (2.5) | Scared of animals and people | 366 | 208 (56.8) | 115 (31.4) | 43 (11.7) |

| Always asks for help | 364 | 168 (45.9) | 101 (27.6) | 95 (26.0) | Cruel to animals | 365 | 343 (93.7) | 14 (3.8) | 8 (2.2) |

| In a hurry | 366 | 152 (41.5) | 100 (27.3) | 114 (31.1) | Hurts others unintentionally | 366 | 333 (91.0) | 25 (6.8) | 8 (2.2) |

| Dependent on adults | 365 | 176 (48.1) | 78 (21.3) | 111 (30.3) | Fights a lot | 365 | 267 (73.0) | 70 (19.1) | 28 (7.7) |

| Scared to try new things | 365 | 274 (74.9) | 75 (20.5) | 16 (4.4) | Gets physically hurt a lot | 366 | 209 (57.1) | 96 (26.2) | 61 (16.7) |

| Demanding | 366 | 12 (3.3) | 29 (7.9) | 324 (88.5) | Punishment does not improve actions | 366 | 305 (83.3) | 46 (12.6) | 15 (4.1) |

| Cries a lot | 366 | 122 (33.3) | 136 (37.2) | 108 (29.5) | Hits others | 364 | 317 (86.6) | 36 (9.8) | 11 (3.0) |

| Hyperactive | 365 | 132 (36.1) | 80 (21.9) | 153 (41.8) | Does not like to leave the house | 364 | 337 (92.1) | 19 (5.2) | 8 (2.2) |

| Can be hurt easily | 364 | 149 (40.7) | 142 (38.8) | 73 (19.9) | Complains a lot | 366 | 259 (70.8) | 82 (22.4) | 25 (6.8) |

| Destroys stuff | 366 | 167 (45.6) | 141 (38.5) | 58 (15.8) | Sad for no reason | 364 | 330 (90.2) | 27 (7.4) | 7 (1.9) |

| Does not like change | 364 | 289 (79.0) | 57 (15.6) | 19 (5.2) | Easily embarrassed | 365 | 293 (80.1) | 53 (14.5) | 19 (5.2) |

| Disobedient | 364 | 194 (53) | 88 (24) | 84 (23) | Moody | 365 | 150 (41) | 70 (19.1) | 145 (39.6) |

| Interferes with everything | 365 | 255 (69.7) | 49 (13.4) | 61 (16.7) | Short-tempered | 364 | 163 (44.5) | 68 (18.6) | 133 (36.3) |

| Does not sleep alone | 366 | 196 (53.6) | 56 (15.3) | 114 (31.1) | Obsessed about cleaning | 364 | 33 (9.0) | 60 (16.4) | 271 (74.0) |

| Does not fall asleep easily | 365 | 258 (70.5) | 51 (13.9) | 56 (15.3) | Loud | 365 | 144 (39.3) | 27 (7.4) | 193 (53.0) |

| Wakes up several times a night | 364 | 250 (68.3) | 77 (21.0) | 37 (10.1) | Shouts always | 366 | 222 (60.7) | 36 (9.8) | 108 (29.5) |

| Resists going to bed at night | 366 | 262 (71.6) | 63 (17.2) | 41 (11.2) | Lacks passion | 366 | 346 (94.5) | 12 (3.3) | 8 (2.2) |

| Is annoyed by new people | 363 | 306 (83.6) | 53 (14.5) | 4 (1.1) | Clumsy | 364 | 359 (98.1) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) |

Statistical methods

Data were entered using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and analysed in SPSSv22.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Demographic variables are presented as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables are reported as frequencies and percentages. The associations among pregnancy cravings, type of delivery, vitamin and iron treatment, and child behaviours were examined using chi-square tests. Associations between pregnancy cravings and other pregnancy factors (such as time of delivery) were also examined using chi-square tests. Associations between child behaviours and maternal age were examined using Pearson's correlation coefficients. Significance was set at the P < .05 level.

Results

A total of 366 women were included in the study, with a mean child age of 44.11 ± 15.65 months. Among the children, 204 (55.7%) were females, and 162 (44.3%) were males. The majority of women were given iron treatment (n = 356, 97.3%) and used vitamins (n = 359, 98.1%) during their pregnancy. Most (n = 280, 76.5%) of them also had a normal, on-time delivery (n = 355, 97%).

A total of 83.1% (n = 304/366) of the women experienced cravings. The most common reported food craving, experienced by one-third of the women (n = 112), was for fruit, namely lemons (n = 27, 75%) and oranges (n = 15). Other common cravings included salty crackers (n = 40, 10.9%), sweets (n = 35, 9.6%), meat (n = 32, 8.7%), vegetables (n = 29, 7.9%), savoury food (n = 28, 7.7%), and dairy (n = 18, 4.9%; Table 1; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Food craving group.

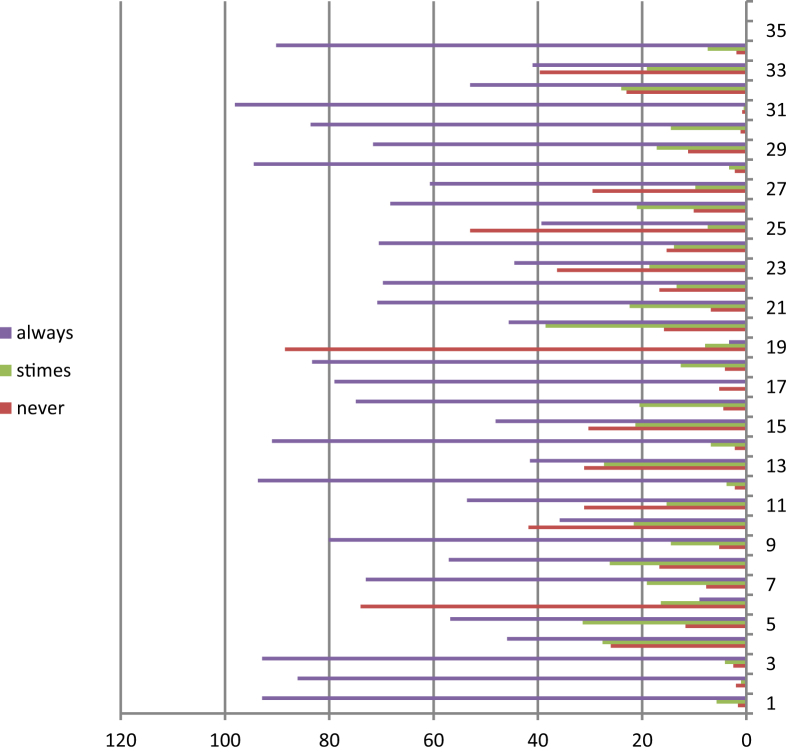

All children were reported to have at least two behavioural issues (range = 2 to 34; mean = 14.74 ± 6.16; Table 2). The total number of behavioural issues was negatively correlated with child age (r = −.26, P < .001). Women who experienced cravings were significantly more likely to report that their child was obsessed with cleaning (P = .03) and significantly less likely to report that their child was sad for no reason (P = .003), scared to try new things (P = .04), interfered with everything (P = .01), got frustrated easily (P = .04), or was moody (P = .03; Table 2; Figure 2) No other associations were observed; however, trends were observed for an increased likelihood of acting younger than their age and not being able to cope with peers compared with children of women who had not experienced pregnancy cravings.

Figure 2.

Bahavioural issues.

There was no significant difference in the average number of behavioural problems between children whose mothers experienced pregnancy cravings and those whose mothers did not. There was also no association between cravings and child gender. However, women who experienced cravings were significantly more likely to have a normal delivery (P = .001). Owing to the small number of women who had pre-term deliveries, did not receive iron treatment, or did not take vitamins during their pregnancy, associations could not be examined between these characteristics and child behaviour problems.

Discussion

Although the occurrence of cravings during pregnancy is common, little research has examined the potential impact of cravings on foetal development and future child development. In this retrospective study, we examined whether the presence of cravings during pregnancy was associated with challenging child behaviours. The majority of women sampled had experienced pregnancy cravings. However, we found little evidence regarding the association between child behavioural issues and pregnancy cravings.

The proportion of women who reported cravings in our study was in line with previous literature (i.e. 50–90%10). For example, in a study of 204 pregnant and lactating Tanzanian women, 73.5% reported experiencing cravings, and in a study of 161 American participants, 86% reported experiencing cravings.11 The common cravings identified in the present study, including fruit and sweets, are also in line with prior work.12, 13 Alternatively, studies have suggested that cravings are very much influenced by the food that is regionally and culturally available; therefore, the high incidence of cravings for salty and savoury food in the present sample could be due to the culinary culture in Jordan.14 Previous studies have suggested that cravings may change throughout a woman's pregnancy, with savoury food more likely to be craved during the first trimester and sweet food cravings more common in the second trimester.15 Because we did not determine whether women had experienced pre-pregnancy cravings, we cannot definitively conclude why the high rate of salty food cravings was observed in the present study relative to previous studies. Differences in food cravings may depend on when women are questioned. For example, we interviewed non-pregnant women who had children no younger than 18 months. Thus, perhaps they were not able to retrospectively recall the cravings experienced during their entire pregnancy very clearly though we did exclude patients with unsure answers. However, our results could be limited by a potential recall bias given the long time that had elapsed since those cravings were experienced. Conversely, sampling women during their pregnancy could facilitate a recency bias in terms of reported cravings. Thus, there are costs and benefits with regards to the assessment time chosen.

Development is the term used to describe the changes in a child's physical growth, as well as his or her ability to learn the social, emotional, behavioural, thinking, and communication skills needed throughout life. All of these areas are linked, and each depends on and influences the others. In the first 5 years of life, the child's brain develops more and faster than at any other time in their life. The child's early experiences—his or her relationships and the things he or she sees, hears, touches, smells, and tastes—stimulate the brain, creating millions of connections. This is when the foundations for learning, health, and behaviour throughout life are laid down. How does child development happen? In the early years, the child's main way of learning and developing is through play. Much of the child's time is spent playing, talking, listening, and interacting with their surroundings, which helps him or her learn the skills needed for life. These skills include communicating, thinking, solving problems, moving, and being with other people and children. Being physically active develops motor skills, helps thinking, and gives the child an opportunity to explore his or her world. Chronic or long-term conditions can affect child development. These include developmental and learning disabilities such as autism spectrum disorder. Healthy eating habits aid in developing a child's sense of taste. In our study, we wanted to see if maternal dietary cravings in pregnancy were related to children's behavioural development.16, 17

The children in the present study demonstrated some sort of behavioural challenge, with a majority of women reporting 5 to 20 different problems. However, variability in behaviours was not significantly related to pregnancy cravings, as no differences in the total number of behavioural problems were reported between women who did or did not experience cravings. We did observe that behavioural problems were associated with the child's age, suggesting that our lack of association between behaviours and cravings could be due to the age range of children sampled. For instance, it is possible that a reported behaviour problem may have been influenced by the particular time and place it occurred and may not, therefore, account for challenging behaviours that are now resolved. Given the relatively large age range sampled, along with the developmental milestones that occur during the first 5 years of life, interrogating behaviour problems can be difficult based on what would be expected as ‘age-appropriate’ for a particular developmental period. Unfortunately, there was an insufficient number of participants for properly exploring associations within tighter age ranges. A larger study, with children at the same developmental level, may enable the discovery of significant associations between child behaviours and pregnancy cravings.

A few additional limitations should be noted. As discussed above, a recall bias could have been a potential confound given the relatively long period of time since the women in our sample had been pregnant, suggesting the need to assess reported cravings before, during, and after the pregnancy. Additionally, we could not adequately address some potentially important covariates given the sample size limitations within subgroups (i.e. women with pre-term deliveries). Thus, expanding our sample to include these subgroups would be beneficial in the future.

Conclusions

In summary, the present study revealed a high incidence of pregnancy cravings, which is in line with previous studies in other populations. However, although child behavioural problems were commonly reported, these issues were not related to whether mothers experienced cravings during the pregnancy.

Source of funding

None.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with standards outlined by the ethics committee of Jordan University of Science and Technology and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Authors' contributions

AL-MEHAISEN is a Gynecologist that responsible for the Ideas of the study, how the study was conducted and writing. AL-KURAN is responsible for data collection and preparing the proposal of the study. AL-HUSBAN and MATALKA were involved in analysis of the data and writing the manuscript. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

Patients and data extraction

This was a retrospective study assessing healthy non-pregnant women attending a gynaecology outpatient unit at King Abdullah University Hospital (a tertiary and referral centre), Jordan, for non-pregnancy-related issues, from January 2014 to January 2015.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- 1.Bayley T.M., Dye L., Jones S., DeBono M., Hill A.J. Food cravings and aversions during pregnancy: relationships with nausea and vomiting. Appetite. 2002;38:45–51. doi: 10.1006/appe.2002.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belzer L.M., Smulian J.C., Lu S.E., Tepper B.J. Food cravings and intake of sweet foods in healthy pregnancy and mild gestational diabetes mellitus. A prospective study. Appetite. 2010;55:609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowen D.J. Taste and food preference changes across the course of pregnancy. Appetite. 1992;19:233–242. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flaxman S.M., Sherman P.W. Morning sickness: a mechanism for protecting mother and embryo. Q Rev Biol. 2000;75:113–148. doi: 10.1086/393377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orloff N.C., Flammer A., Hartnett J., Liquorman S., Samelson R., Hormes J.M. Food cravings in pregnancy: preliminary evidence for a role in excess gestational weight gain. Appetite. 2016;105:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gendall K.A., Joyce P.R., Sullivan P.F. Impact of definition on prevalence of food cravings in a random sample of young women. Appetite. 1997;28:63–72. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hook E.B. Dietary cravings and aversions during pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31:1355–1362. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/31.8.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill A.J., Cairnduff V., McCance D.R. Nutritional and clinical associations of food cravings in pregnancy. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:281–289. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser L.L., Allen L., American Dietetic Association Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition and lifestyle for a healthy pregnancy outcome. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1479–1490. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King J.C. Physiology of pregnancy and nutrient metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1218S–1225S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1218s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nyaruhucha C.N. Food cravings, aversions and pica among pregnant women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2009;11:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oberto A., Mele P., Zammaretti F., Panzica G., Eva C. Evidence of altered neuropeptide Y content and neuropeptide Y1 receptor gene expression in the hypothalamus of pregnant transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4826–4830. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pope J.F., Skinner J.D., Carruth B.R. Cravings and aversions of pregnant adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92:1479–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tierson F.D., Olsen C.L., Hook E.B. Influence of cravings and aversions on diet in pregnancy. Ecol Food Nutr. 1985;17:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Worthington-Roberts B., Little R.E., Lambert M.D., Wu R. Dietary cravings and aversions in the postpartum period. J Am Diet Assoc. 1989;89:647–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Health and Medical Research Council . NHMRC; Canberra: 2013. Australian dietary guidelines. Retrieved 17 April 2018 from. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Scientific Council on the Developing Child . Centre on the Developing Child, Harvard University; Cambridge, MA: 2004. Young children develop in an environment of relationships. Working paper no. 1. Retrieved 17 April 2018 from. [Google Scholar]