Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to develop knowledge about the preferred learning styles of Saudi nursing students that can lead students to understand course content and, in turn, offer improved patient care.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey design was administered to 125 female nursing students who volunteered to participate in this research.

Results

The majority of participants (80.5%) had some preference for kinaesthetic learning. Of those with a dominant preference, 38.2% had a strong preference for kinaesthetic learning, while 10.6%, 4.9%, and 2.4% preferred aural, reading/writing, and visual learning, respectively. The learning styles of Saudi nursing students were not significantly different in their kinaesthetic preference from one group of Australian nursing students (p = 0.85) but were significantly different in their kinaesthetic preference (p < 0.0001) from Saudi medical students. The kinaesthetic learning style was the highest ranked preference for all groups of nursing students.

Conclusions

The reported learning styles of Saudi nursing students were more similar to other groups of nurses than they were to other Saudi healthcare students in key areas of learning preference.

Keywords: Interprofessional, KSA, Learning styles, Nurse, VARK

الملخص

أهداف البحث

تهدف هذه الدراسة لمعرفة أسلوب التعلم المفضل لطالبات التمريض السعوديات، الأمر الذي يؤدي إلى فهم محتوى المنهج وبالتالي تحسين رعاية المرضى.

طرق البحث

وزعت استبانة مسحية مقطعية على ١٢٥ طالبة تمريض سعودية تطوعت بالاشتراك في هذا البحث.

النتائج

فضل أكثر من ٨٠.٥٪ من المشاركات التعلم الحركي. وفضلت بقوة ٣٨.٢٪ منهن التعلم الحركي، في حين هيمن تفضيل ١٠.٦ ٪٬ و ٤.٩٪ و ٢.٤٪ للتعلم السماعي، والقراءة/الكتابة، والتعلم البصري، على التوالي. ولم تكن أساليب التعلم لطالبات التمريض السعوديات مختلفه كثيرا في تفضيلهن التعلم الحركي عن مجموعة طالبات التمريض الاستراليات، ولكن كانت مختلفة إلى حد كبير في تفضيل التعلم الحركي عن طالبات الطب السعوديات. وحصل أسلوب التعلم الحركي على أعلى رتبة تفضيل بين جميع مجموعات طالبات التمريض.

الاستنتاجات

كانت أساليب التعلم المذكورة لطالبات التمريض السعوديات أكثر مماثلة لمجموعات أخرى من الممرضات عن طالبات التخصصات الصحية السعوديات في مجالات رئيسة لتفضيل أساليب التعلم.

الكلمات المفتاحية: التعليم المتداخل بين التخصصات, أساليب التعلم, ممرضة, المملكة العربية السعودية

Introduction

Student populations at universities in the Middle East and throughout the world are diverse. Students come from a variety of backgrounds, experiences, cultures and learning style preferences. In KSA, students often enter undergraduate nursing programmes directly from high school. Many of the students were previously taught using rote learning and memorization. They likely had little choice in the types of projects that they participated in, and the ways of teaching and learning that were utilized. During the foundational years at Saudi universities, much of the learning is centred on language, math, and basic sciences. Again the predominant teaching style in those programmes is didactic, and centres on the students ’abilities to memorize facts.

When students' reach health professional programmes such as nursing at universities, they encounter a variety of different ways of being taught and ways of learning. As they enter professional programs, they begin to take courses that require more hands-on learning, reading, writing, critical thinking and independent learning. Previous to this study, the learning style preferences of Saudi nursing students was not known. Developing knowledge of the different learning styles will help nursing faculty to develop curricula and adopt teaching methods that will be enjoyable to students and likely impact their learning environment.

Ultimately, faculty in the healthcare colleges want to help students to become the type of practitioners who will positively impact patient care. Faculty also hope that their students become lifelong learners. It is the goal of the nursing faculty to creatively develop education techniques that are compatible with the preferred learning styles of their students. Nursing student learning preferences must be understood to most effectively develop methods that will result in educating well-prepared nursing professionals.

The aim of this study was to understand the predominant learning style preferences of Saudi nursing students. We hypothesized that the learning style preferences would be different from Western nursing students and more similar to other Saudi healthcare students.

A number of models have been designed to assess learning styles, with some focusing on the students' personalities as much as on how they like to acquire information. Most tools that are designed to examine learning styles focus on the following: where they like to learn, which of their senses they rely on the most, personality type, and their cognitive style.1 For this study, the VARK (Visual, Aurel, Read/Write and Kinaesthetic) Learning Styles Inventory was chosen because it measures preference (not personality), is time-efficient (comprised of only 16 questions) and simply worded. Furthermore, the VARK has already been successfully used with Saudi Arabian students and in other countries in the Middle East with a variety of different groups of learners. The questions are multiple choice with four possible answers. The questions are intuitively understood, and the results are easy to understand and interpret. The VARK learning style inventory was tested for reliability coefficients, which were found to be adequate.2

Nursing education in KSA is evolving. While nursing in the region has not been traditionally viewed as a highly respected profession, over time, more Saudi nationals have been entering the nursing profession.3 High school students are encouraged to pursue nursing, as their tuition and books are free, and students are given a stipend to attend government university nursing programmes.

This study took place in Riyadh (population of approximately 3.5 million), which is the capital city of KSA.4 The College of Nursing at Princess Nourah University (PNU) offers a Bachelor's Degree in Nursing, and serves an increasing number of new students each year. PNU is the largest all-female university in the world.

In Saudi nursing education, a greater emphasis has been put on improving clinical skill practice, enhancing the simulated learning environment and using case-based learning. The nursing programme at PNU has been moving away from a didactic curriculum towards one that is more interactive. Instructors are using case studies, practical activities in smaller seminar groups, and an excellent, well-equipped simulation laboratory. Traditional methods of nursing students' learning such as in reading and writing have been met with resistance and low effort on the part of the students. Although reading and writing are clearly important and necessary abilities to develop, they are not the only methods through which nursing students can learn.

The PNU faculty are keen to present an effective curricula and teaching methodology to guide student nurses to understand essential nursing knowledge and skills. Therefore, the authors set out to better understand what was required to develop the competencies and skills to practice nursing in the Saudi context. The authors believe that one import aspect of efficient curriculum content delivery is using a variety of teaching styles that are appealing to the students. Therefore, the goal was to first understand the learning style preference of this cohort of nursing students.

Before using any tool, culture and language should be considered. Cross-cultural validation and translation of existing internationally recognized surveys is not new.5 To find the students' learning style preferences, the authors used translation and back-translation to develop a modified VARK. The authors also enrolled young Saudi nurses into focus groups, and in-depth interviews to establish culturally suitable questions. The researchers' intent was to adapt the questions so that they were non-offensive to PNU's Saudi female population, and at the same time did not lose the original meaning. A small pre-testing with student feedback was also carried out (10 students). The final version of the adapted tool was also reviewed and approved by the original creator of the VARK learning styles inventory (Dr. Neil Fleming) and his feedback was incorporated into the tool. The pre-tested questionnaires were not included in this analysis as some of the questions were modified. In the end, the participants reported that the questionnaire made sense to them and were appropriate for this young, all-female, Saudi Arabian population.

A number of studies have been conducted to examine how nursing students learn. These studies have looked at different aspects of learning such as clinical skills and simulation, instructor-led and peer-lead education, and the use of games.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 In the PNU context, faculty were highly motivated by the need to understand how nursing students liked to learn. In choosing to use the VARK learning styles inventory, the researchers could answer this primary question and also inform students on their particular preferences. The study team sought to find all of the articles from the published literature that measured learning style preferences using the VARK on populations of nursing students.

On May 18, 2016, the researchers used the search engines of MEDLINE and CINHAL to conduct a literature review. The aim of this literature search was to identify articles from the published literature that had used the VARK learning styles inventory with nurses or nursing students. The keywords, “VARK” or “VARK learning style*” and “nurs*” were entered into the search engines. In total, there were 88 unique articles identified. Inclusion criteria included all articles that study learning style preference with nurses or nursing students.

Seven results were found in the literature that described projects where nursing students used the VARK learning styles inventory to assess learning styles.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 No studies were found that reported results on the use of VARK with nursing students in KSA. Studies using VARK with populations of university students in other professions from KSA were found in the literature.19, 20, 21, 22, 23

Although there has been question about the utility of knowing students' learning style preferences,24 there has also been evidence of its value. For example, a study of Australian nursing students found evidence that having a strong kinaesthetic sensory mode was a predictor of academic success (p = 0.009).16 Another study from China reported that academic performance was significantly related to learning style.7 The purpose of the literature review was to understand what had been written previously about student nurses' learning style preferences.

Materials and Methods

A proposal outlining the scientific and ethical considerations was submitted to the College of Nursing's Internal Research Ethics Board. Permission to conduct the study was received. Students who chose to participate were asked to sign a consent form.

Using a cross-sectional design, the researchers distributed the culturally adapted Arabic version of the VARK to 125 students ranging from 2nd to 4th year. The sample size calculation showed that to have 5% error and a 90% confidence level the total sample size would need to be at least 107 student nurses. All nursing students who were studying at the university were invited to participate. The research team sought to enrol at least one-third of all available nursing students. The front page of the survey included an explanation of the project (in the Arabic language) and emphasized the voluntary nature of the students' participation.

Each group of students was invited to participate in the study through an announcement made at the end of nursing theory classes. The researchers explained the purpose of the project and distributed the questionnaires to those who were interested in participating. Students were encouraged to consider each question carefully and choose the best answer. Where there were two or more answers that were all equally accurate in describing the student's preference, the student was encouraged to choose multiple answers. The time required for each group to complete the questionnaire was between 15 and 20 min.

The data were then collected, entered into the computer, and collated. Each student's results were calculated to identify their learning style preference. The overall results were then grouped into those who had a single strong preference for either visual, aural, reading/writing, or kinaesthetic (V, A, R and K) or were multi-modal. Multi-modal means that they had a strong preference for two strong learning preference modalities (bimodal: VA, VR, VK, AR, AK and RK); three strong preferences (trimodal VAR, VAK, VRK and ARK); or all of the learning styles (quadrimodal-VARK).

Results

In total, 125 responses were received. This represented approximately 45% of the 278 women in the nursing programme. This exceeded the goal of reaching at least 1/3 of the student nurse population enrolled at the PNU College of Nursing, and the sample size calculation of 107 students. One critical issue experienced by the researchers in enrolling students into the study was that many students were absent from the College and participating in clinical practice. The practice took place throughout the city and in some instances outside of the city. A large proportion of students were also enrolled in their internship and working shift work. As a result, many of the students were not available to participate in the study.

Nursing students' preferences for how they receive and understand information may be predominantly unimodal (a strong single preference in how they like to learn), bimodal (two learning style preferences), trimodal, or all four (VARK). This study revealed that the population that was measured preferred a single mode of learning in 56.1% of the cases (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Learning style preferences.

| Unimodal | Bimodal | Trimodal | All VARK | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual | 2.4% | Aural/Kinaesthetic | 9.8% | Aural/Read & Write/Kinaesthetic | 4.1% | 20.3% |

| Aural | 10.6% | Visual/Kinaesthetic | 5.7% | Visual/Read & Write/Kinaesthetic | 1.6% | |

| Read/Write | 4.9% | Visual/Read & Write | 0.8% | Visual/Aural/Kinaesthetic | 0.8% | |

| Kinaesthetic | 38.2% | Visual/Aural | 0.8% | |||

Of the total population, a full 80.5% had at least some preference for kinaesthetic learning. These types of students are well suited for nursing, as they prefer a hands-on approach to learning, which will serve them well for life-long learning. From this result, we conclude that these nursing students enjoy learning by doing.

Only about one-fifth of the female nursing students had no specific preference for learning style. Of the students who preferred three modes of learning (6.5%), all of them included the kinaesthetic style. The majority of students in the study had a strong preference for one of the four learning styles over the others (56.1%). This finding was higher (ranging from 2.1% more to 36.1% more) than the unimodal findings, measuring the VARK Learning Styles Inventory, as found in the published literature (see Table 2). Additionally, for comparison purposes the results of two studies in Saudi Arabian populations are included: one of medical students and the other of dental students.23, 20

Table 2.

Comparison of the study results to other nursing student results from the literature: unimodal verses multimodal.

| Study | Population | % multimodal | % different from PNU nursing students |

|---|---|---|---|

| PNU nursing students | 125 female Saudi Arabian nursing students | 43.9% | |

| Meehan-Andrews, 200918 | 86 Australian nursing students | 46% | +2.1 |

| Alkhasawneh 201312 | 197 Jordanian nursing students (pre-test) | 54% | +10.1 |

| Albidia 201625 | 84 Saudi Arabian female dental students | 54.7% | −10.8% |

| Koch et al., 201116 | 62 Australian nursing students | 62% | +18.1% |

| Good et al., 201315 | 24 US nursing students | 66.7% | +22.8% |

| James et al., 201117 | 334 Australian nursing and midwifery students | 80% | +36.1% |

| Nuzhat et al., 201123 | 76 Saudi Arabian medical students | 72.6% | +28.7% |

| Al-Saud, 201320 | 113 Saudi Arabian dental students | 59% | +15.1% |

| Asiry, 201422 | 269 male Saudi Arabian dental students | 58.4% | +14.5% |

Discussion

Nursing is a very active profession that requires the ability to perform a great variety of clinical skills. The female Saudi nursing students in this study show a high preference for hands-on learning. The Saudi nursing students appear to have more in common with student nurses from Australia in relation to their learning style preferences than they do with other health profession students from KSA (see Figure 1). For example, when looking at those students who had a unimodal preference, the PNU students were not significantly different in their kinaesthetic preference (Chi-squared 0.04, 95% CI -13 to 15, p = 0.85) from Australian nursing students from Victoria.18 However, the students in the current study were significantly different in their kinaesthetic preference (Chi-squared 30.1, 95% CI 20 to 40, p < 0.0001) from Saudi medical students.23 The kinaesthetic learning style was the highest ranked preference for all groups of nursing students.

Figure 1.

Comparison of unimodal learning style results – nursing students.

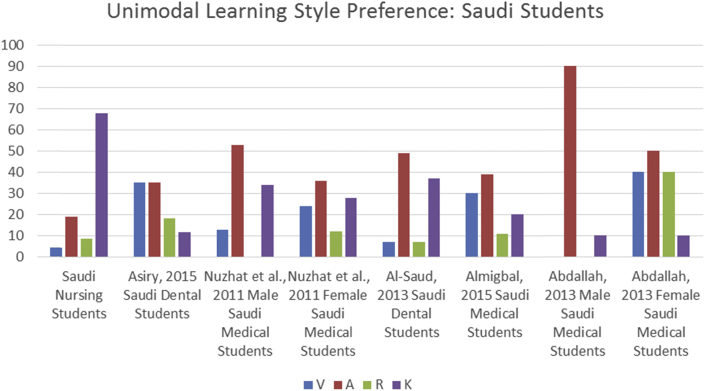

Saudi female nursing students also had a similar preference for learning by listening than other nursing student populations (at 19% of the unimodal responses). However, all nursing student unimodal Aurel proportions were much lower than other Saudi healthcare populations, which reported for the unimodal Aurel preferences ranging from 36%23–90%21. A comparison of the current study with other nursing student populations is outlined in Figure 1, while a comparison of the current study's unimodal results with other Saudi VARK responses is included in Figure 2. None of the groups of nursing students had a strong preference for the visual style of learning or learning through watching.

Figure 2.

Comparison of unimodal learning style results – Saudi dental and medical students.

Many of the Saudi healthcare students enjoyed aural learning. This learning preference is strong in a number of Saudi populations. Students who prefer aural learning enjoy receiving information that is spoken or heard. Aural learners often use questioning as a learning strategy. In one study,21 Saudi male medical student respondents who had unimodal learning style preference did not have any strong preference for visual or reading/writing. In that same study, very few male and female students had a strong kinaesthetic learning style preference (both only 10%).

The current study demonstrated that nursing students from KSA were more unimodal in the responses to the VARK learning inventory than the other nursing students or Saudi healthcare students found in the published literature. In comparison to one group of Saudi medical students23 there was a nearly 29% difference in the number of students reporting multimodal learning style preferences (Chi-squared 15.6, 95% CI 14 to 42, p = 0.0001). However, there was no significant difference (Chi-squared 0.09, 95% CI -12 to 16, p = 0.76) between the current study and one group of Australian nursing students.18 Even with a country, results may vary. Interestingly, the other group of Australian nursing students17 (which included rural students and 10% males) was the most different from PNU students in their multimodal preferences (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

When the results of the current study were compared to other nursing student populations and also to a population of medical students in KSA, it was clear that this group of students had a stronger preference for “learning by doing” than others. A similarly strong result for kinaesthetic preference was also observed in one group of Australian students.18 Saudi nursing students also had less preference for reading and writing than all other nursing students included, but higher than that of some Saudi medical and dental students (see Figure 1, Figure 2).

It is important for nurse educators to know about the variety of learning style preferences of their students. In doing so, they can more accurately and efficiently meet their learning outcomes. Using a variety of teaching styles will assist in delivery of the educational content in a way that is most accepted by the majority of students. Clearly, the faculty's goal is not just student knowledge acquisition but eventually, for students to be able to understand the information, apply it, and move towards critical thinking and creativity.

People are individual, and yet, there is value in knowing the dominant preferences in a group of students. Educators and curricula designers must be aware of the importance of learning by doing, particularly in groups similar to these students. Prior to knowing about the dominant kinaesthetic and aural learning styles, a great deal of time was spent in the nursing lab on demonstration of skills. Students watched their instructors performing the tasks or watched videos. There were times when some students did not even practice the skill once during a lab session. After knowing learning style preferences, the teaching methodology has changed. More attention is being paid to engaging the students through acting out case studies during lab time, and repeatedly practicing skills on each other and on mannequins. The ways of assessing students have also changed. Instructors are relying less on quizzes and papers and now students are also being assessed kinaesthetically as well, using Objective Structured Clinical Examinations.

Recommendations

Reading, writing papers, and watching demonstrations and videos are an important part of student learning. However, a greater proportion of the nursing programme should focus on hands-on lab and clinical experiences, if the students are found to enjoy learning by doing. Simulation experiences are also important, including the debriefing sessions, which appeal to both kinaesthetic and aural-preference learners. Once nursing faculty learn the predominant learning style preferences of their students, they too can reconsider their educational delivery to tailor the learning experience to their students' inclinations.

An area for future study may be to assess any relationships between learning style preference and academic performance. In one study from the United States, researchers tested nursing students to see if having a read/write learning style preference might predict their academic success.16 While this study found no relationship between the read/write preference and high GPA, it did reveal that having a strong kinaesthetic learning style preference was a positive and significant predictor of academic performance. More research could be conducted to assess different methods of learning and nursing student academic success.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors' contributions

BVS conceived and designed the study, conducted and collected the research with WAA, and organized data. WAA conducted and collected research and collaborated on the translation work for the project. BVS wrote initial and final draft of article. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- 1.Cook D.A., Smith D.J. Validity of index of learning style scores: multitrait-multimethod comparison with three cognitive/learning style instruments. Med Educ. 2006;40:900–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leite W.L., Svinicki M., Shi Y. Attempted validation of the scores of the VARK: learning styles inventory with multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis models. Educ Psychol Meas. 2010;70:323–339. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clerehan R., McCall L., McKenna L., Alshahrani K. Saudi Arabian nurses' experiences of studying Masters Degrees in Australia. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(2):215–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia Tokyo: facts and Figures [Internet]. Population [cited 2016 Oct 14] Available from: http://www.saudiembassy.or.jp/En/SA/SA.htm.

- 5.Vanti C., Bonetti F., Ceron D., Piccarreta R., Violante F.S., Guccione A., Pillastrini P. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the physical therapy outpatient satisfaction survey in an Italian musculoskeletal population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;5(14):125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Modhefer A., Roe S. Nursing students' attitudes to biomedical science lectures. Nurs Stand. 2009;24(14):42–48. doi: 10.7748/ns2009.12.24.14.42.c7435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y., Yu W., Liu C., Shieh S., Yang B. An exploratory study of the relationship between learning styles and academic performance among students in different nursing programs. Contemp Nurse A J Aust Nurs Prof. 2014;48(2):229–239. doi: 10.5172/conu.2014.48.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNett S. Teaching nursing psychomotor skills in a fundamentals lab. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2012;33(5):328–333. doi: 10.5480/1536-5026-33.5.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts T.E., Pomarico C.A., Nolan M. Assessing faculty integration of adult learning needs in second-degree nursing education. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2011;32(1):14–17. doi: 10.5480/1536-5026-32.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Secomb J.A. Systematic review of peer teaching and learning in clinical education. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(6):703–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blakely G., Skirton H., Cooper S., Allum P., Nelmes P. Educational gaming in the health sciences: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(2):259–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkhasawneh E. Using VARK to assess changes in learning preferences of nursing students at a public university in Jordan: implications for teaching. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(12):1546–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alkhasawneh I.M., Mrayyan M.T., Docherty C., Alashram S., Yousef H.Y. Problem-based learning (PBL): assessing students' learning preferences using VARK. Nurse Educ Today. 2008;28(5):572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourgault A.M., Mundy C., Joshua T. Comparison of audio vs. written feedback on clinical assignments of nursing students. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2013;34(1):43–46. doi: 10.5480/1536-5026-34.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Good J.P., Ramos D., D'Amore D.C. Learning style preferences and academic success of preclinical allied health students. J Allied Health. 2013;42(4):e81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch J., Salamonson Y., Rolley J.X., Davidson P.M. Learning preference as a predictor of academic performance in first year accelerated graduate entry nursing students: a prospective follow-up study. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31(6):611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James S., D'Amore A., Thomas T. Learning preferences of first year nursing and midwifery students: utilising VARK. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31(4):417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meehan-Andrews T.A. Teaching mode efficiency and learning preferences of first year nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2009;29(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Almigbal T.H. Relationship between the learning style preferences of medical students and academic achievement. Saudi Med J. 2015;36(3):349–355. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.3.10320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Saud L.M. Learning style preferences of first-year dental students at King Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: influence of gender and GPA. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(10):1371–1378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdallah A., Al-zalabani A., Alqabshawi R. Preferred learning styles among prospective research methodology course students at Taibah University, Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2013;88(1):3–7. doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000427506.57924.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asiry M.A. Learning styles of dental students. Saudi J Dent Res. 2015;7:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuzhat A., Salem R.O., Quadri M.S.A., Al-Hamdan N. Learning style preferences of medical students: a single-institute experience from Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman G. When will learning style go out of style? Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s10459-009-9155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abidia R.F., Stirling B., Azam A., El-Hejazi A., Al-Dukhail S. Assessing dental students' learning style preference. J Health Commun. 2016;2(1) [Google Scholar]