Abstract

Objective

This study explores the role of knee circumference, body mass index (BMI), and range of motion (ROM) in predicting knee osteoarthritis (KOA). The objective is to elucidate the mediating role of BMI in influencing the relationship between age, knee circumference and pain in knee osteoarthritis, as measured with the help of the knee outcome survey (KOS) questionnaire.

Methods

The design used in this study was causal comparative. The study consisted of 66 patients with symptomatic KOA and 60 matched asymptomatic individuals.

Result

BMI was significantly and positively correlated with both pain and knee girth for the symptomatic KOA group. This finding signifies a relationship between KOA and other indicators, such as age and knee circumference.

Conclusions

The results of the study would indicate an important milestone in clinical rehabilitation, especially for physical therapists, enabling them to plan, modify, and design interventions to improve the health status of KOA patients.

Keywords: Body mass index (BMI), Clinical rehabilitation, Knee circumference, Knee osteoarthritis (KOA), Range of motion (ROM)

الملخص

أهداف البحث

تستكشف هذه الدراسة دور كل من محيط الركبة، ومؤشر كتلة الجسم والنطاق الحركي للركبة في التنبؤ بالفصال العظمي للركبة. وتهدف الدراسة إلى إيضاح الدور الوسيط الذي يلعبه مؤشر كتلة الجسم في التأثير على العلاقة بين العمر ومحيط الركبة، والألم في حالات الفصال العظمي للركبة٬ حسب ما تم قياسه باستخدام استبانة ”استطلاع مخرجات الركبة“.

طرق البحث

استخدم في هذه الدراسة تصميم السببية المقارنة. وتكونت الدراسة من ٦٦ مريضا يعانون من الفصال العظمي للركبة المصحوب بالأعراض ويقابلهم ٦٠ فردا مطابقا بدون أعراض.

النتائج

ارتبط مؤشر كتلة الجسم بشكل كبير وإيجابي مع كل من الألم ومحيط الركبة في مجموعة الفصال العظمي للركبة المصحوب بالأعراض. وتعني هذه النتيجة وجود علاقة بين الفصال العظمي للركبة ومؤشرات أخرى كالعمر ومحيط الركبة.

الاستنتاجات

تشير نتائج الدراسة إلى وجود مَعلَم هام في مجال إعادة التأهيل السريري، خاصة بالنسبة لأخصائيي العلاج الطبيعي٬ مما يعينهم على التخطيط والتعديل وتصميم المداخلات بشكل أفضل لتحسين الوضع الصحي لمرضى الفصال العظمي للركبة.

الكلمات المفتاحية: مؤشر كتلة الجسم, محيط الركبة, الفصال العظمي للركبة, النطاق الحركي للمفصل, إعادة التأهيل السريري

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a debilitating musculoskeletal disorder that is particularly common among older adults and characterized by the progressive degeneration of cartilage, as well as concomitant bone hypertrophy.1 A prevalence study in KSA has found that KOA affects a staggering 53% of males and 60.9% of females.2 The most common implicating clinical features of KOA in any country are age3 and pain.4 Factors associated with osteoarthritis are well-researched and include vitamin D deficiency,5 smoking habits, and even religious practice in Asia.6 At the same time, BMI, age, previous knee injury is found to be associated with KOA disability. Restricted joint mobility, particularly flexion of the knee, is found to be a significant determinant of disability in KOA.7

Longitudinal studies have observed that obesity is one of the most important risk factors in KOA.8 Researchers have yet to explore fully the compounding effects of many other variables, but knee pain and age are more important determinants of functional impairments in elderly subjects than the disorder's severity.9 KOA is viewed as a disease affecting older persons, but recent evidence suggests that obesity and traumatic knee injury are documented as risk factors for KOA in younger persons.10 Research has also shown that the severity of KOA relates to a decrease in ROM.11 ROM is a defining feature of KOA as it also contributes to developing activity limitations. Clinical presentation of osteoarthritis is characterized by pain, edema, morning joint stiffness, muscular atrophy, and instability.12 Knee circumference measures the articular volume and it quantifies the extension of the edema making it possible to measure the effectiveness of physical therapy intervention.13 Obesity is also found to increase the development and progression of KOA.14, 15 Manninen et al.16 reported that for every standard deviation increase in BMI (3.8 kg/m2) there is a 40% increase in the risk of developing KOA. Along with patient age, being overweight is significantly associated with KOA, potentially leading to an increase in the risk of developing arthritis by between two- and seven-fold.17, 18 KOA is prevalent in countries in the Gulf region because of their ageing populations and growing obesity rates.24 The disorder frequently results in increased girth through inflammation19 and influences patients' ROM. To develop an understanding of the mediating role of BMI, the study uses mediation analysis. There is a dearth of research studies in KSA that establish the mediating effect of BMI in understanding KOA. A Knee Outcome Survey-Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADL) is considered a common tool professionals use to measure the health status of KOA patients.20 The KOS-ADL is also used to measure the KOS-ADL knee function in asymptomatic healthy adults during daily activities of living and sports.

This study has three objectives. The primary objective is to establish the reliability and validity of the KOS-ADL questionnaire commonly used in evaluating the Saudi Arabian population's health. The second objective is to elucidate the effects of age, BMI, ROM and girth on the KOS-ADL of KOA patients while comparing age and BMI with perceived knee function in healthy unrestricted individuals. As a third objective, this study attempts to understand the specific role of BMI as a mediator in influencing the relationships between these variables and KOA pain.

Materials and Methods

Study design and sample characteristics

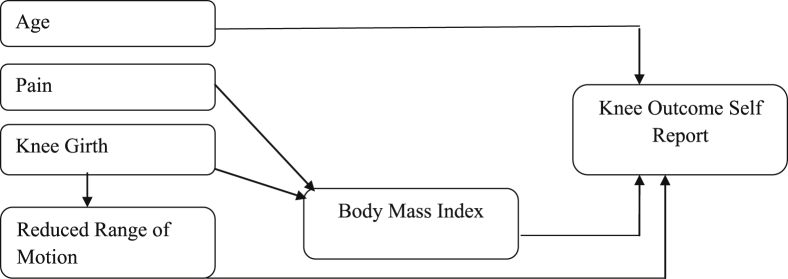

The study had 126 participants. Group 1 consisted of 66 consecutive patients with symptomatic KOA between the ages of 24 and 75 years and Group 2, the control group, which consisted of 60 asymptomatic individuals matched with age. The researcher selected the subjects for Group 1 after obtaining their informed consent and checking the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criterion was referral from the physician with X-ray evidence of degenerative changes in the knee and confirmation by physiotherapy examination. Exclusion criteria included patients who had traumatic injuries other than KOA. Group 2 consisted of individuals who have had no prior history of lower extremity injury or pain. King Khalid University Research Ethical Committee Board reviewed and approved this causal comparative study. The proposed model of the study is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The study model.

Measures

The study took in information regarding the participants' ages, height (in centimetres) and weight (in kilograms). Moreover, the study calculated BMI by weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared. The BMI was then categorized as normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) according to the World Health Organization's (WHO) classification.21 Participants also completed a self-reported questionnaire in the form of the Knee Outcome Survey-Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADL). The assessment was generally considered valid for the assessment of both the symptoms of KOA and physical function disability in patients with KOA.22 It contained eight questions concerning the following symptoms: pain, stiffness, swelling, giving way, weakness, buckling, slipping and limping. There were eight questions regarding functional limitations: walking, ascending and descending stairs, standing, kneeling, squatting, sitting, and rising from a chair. The responses to the assessment were graded on a scale of 0–5, where 5 indicated no limitation and 0 indicated a high level of both symptoms and functional limitations.22, 23 Asymptomatic adults then filled the KOS-ADL perceived knee function form and were exempted from filling out the symptoms section of the questionnaire.

For Group 1, the patient's worse knee was the ‘index’ knee. Researchers/therapists in the study assessed the girth of the index knee in the supine position with the hip in a neutral position; to this end, they placed a rolled towel under the ankle, keeping the knee in an extended and relaxed position while maintaining a zero-degree extension. The therapist stood close to the patient's knee and placed a temporary marker 1 cm above the patella; then, they measured the circumference using a standard measuring tape following exactly the position of the marked line. To measure knee flexion ROM, the therapists asked the patients to lie on the side of their unaffected knee to facilitate assessment. The attendant then applied a plastic baseline universal goniometer to the knee joint lateral femoral condyle, whereby they asked the patient to place their index finger over the greater trochanter, at the same time keeping their immovable arm parallel and their movable arm straight down the leg. The therapist simultaneously held both arms of the goniometer in order to fix the goniometer while passively flexing the knee. Flexion was done up to the point that the patient said ‘stop’ because they had reached their pain threshold. The therapist then noted the degree of flexion after it stopped, then also used a numerical rating scale (NRS) to measure KOA pain based on the patient's present, best, and worst pain levels over the previous 24 h on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable).24

Statistical analysis

Cronbach's alpha and a confirmatory factor analysis helped this study establish the reliability and validity of the KOS-ADL questionnaire. Cronbach's alpha for KOS-ADL was 0.92–0.93.23 Mean and standard deviations describe the sample. A correlation analysis was used to describe the relationship between the variables. Various inferential methods for testing hypotheses about indirect effects have appeared in the literature,25 including the product of coefficient approaches such as the Sobel test,26 bootstrapping,27, 28, 29 and many others. Another tool to establish mediation and moderation is PROCESS30 which provides a single, easy-to-use command for SPSS similar to both the Edwards and Lambert25 and Preacher et al.31 path analysis frameworks.

Results

Questionnaire validation – confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

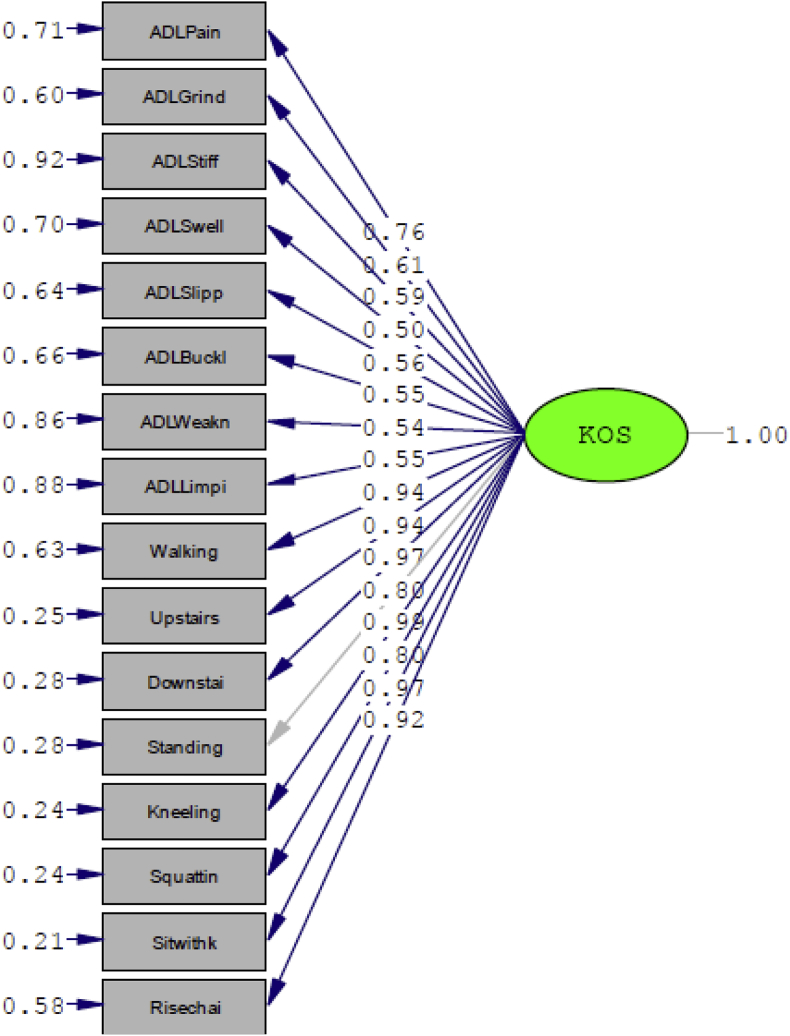

In SPSS-22, the KOS-ADL questionnaire had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.95, indicating a very high internal consistency and high reliability of the questionnaire among the Saudi population. A CFA in LISREL 8.732 showed that the confirmatory model was fit, as demonstrated in Table 3. All the items were loaded in the latent variable and the loadings were high, as shown in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Goodness of fit summary: SPSS and LISREL.

| Cronbach's alpha | Chi square (p value) | GFI | RMSEA | NNFI | CFI | AGFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.953 | 78.66 (0.017*) | 0.98 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.98 |

GFI: Goodness of Factor Index; CFI: Comparative Factor Index; NNFI: Non-normed Fit Index; AGFI: Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation. *p ≤ 0.01.

Figure 2.

CFA-LISREL.

Description of the sample

Group 1 consisted of 66 males; their ages range from 24 to 75, while the mean (±SD) was 50.53 ± 12.706 years. Their mean (±SD) BMI was 29.92 ± 5.59 kg/m2 and 83% were classified as overweight/obese. The mean (±SD) daily level of pain was 7.05 ± 1.55 (scale of 0–10). The knee outcome survey self-reports' mean (±SD) outcome was 45.87 ± 21.05 (ranging from 0 to 100). The mean (±SD) girth was 42.31 ± 5.05. The ROM mean value (±SD) was 126.48 ± 8.35. The control group consisted of 60 males matched for age, the mean (±SD) was 49.05 ± 13.48. Their mean (±SD) BMI was 24.43 ± 3.28 kg/m2. The ROM mean value (±SD) was 135.08 ± 1.4. Mean (±SD) girth was 40.90 ± 7.53. A detailed description is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive data.

| Factors | Mean [±SD] |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.53 ± 12.706 |

| BMI (wt/m2) | 29.92 ± 5.59 |

| NRS (0–10) scale | 7.05 ± 1.55 |

| Girth (cm) | 42.31 ± 5.05 |

| ROM (degrees) | 126.48 ± 8.35 |

| KOS (0–100) scale | 45.87 ± 21.05 |

BMI: body mass index; NRS: Numeric Rating Scale; ROM: Range of Motion-Flexion; KOS: knee outcome survey.

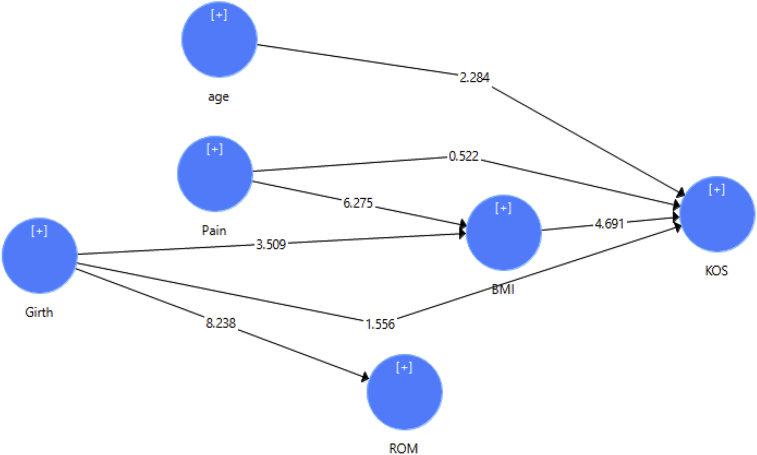

Mediation analysis

To establish mediation, the study used a correlation analysis in SPSS-22, a structural equation bootstrap in PLS-3,33 and SPSS-PROCESS. Analysis showed that BMI correlated to pain (0.300), girth (0.823), and KOS-ADL (0.680) for Group 1, but it is not correlated to the KOS-ADL function for Group 2. Table 2, describes the mediation analysis using bootstrap (500 samples)34 in PLS-3, which shows that all the relationships, except the ROM and KOS-ADL relationships, were significant owing to the fact that their values were greater than ±1.96. The direct effects of pain and girth on KOS-ADL are far less compared to the mediation effects of BMI, shown in Figure 3. PROCESS-SPSS regression analysis shows that pain became non-significant (p = 0.20) when BMI mediates pain and KOS-ADL. Likewise, girth becomes non-significant (p = 0.19) when BMI is added to the equation. Effect size for normal theory tests for indirect effect is 2.63, which is significant at 0.02 for girth and 4.38 significant at p ≤ 0.01 (Table 4, Table 5). Mediation analysis is not conducted for Group 2 since BMI is not correlated to KOS-ADL.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients between KOS and factors affecting knee pain for group-2.

| Factors | Correlation with KOS |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.351** |

| BMI (wt/m2) | 0.382** |

| NRS (0–10) scale | 0.344** |

| Girth (cm) | 0.333** |

| ROM (degrees) | 0.680** |

BMI: body mass index; NRS: Numeric Rating Scale; ROM: Range of Motion-Flexion; KOS: knee outcome survey.

Significant correlations: p ≤ 0.01 in **.

Figure 3.

Bootstrap regression analysis in PLS-3.

Table 4.

Bootstrapping: mediation analysis summary (PROCESS-SPSS).

| Predictors of KOS |

R 2 |

MSE |

F |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| GIRTH-BMI-KOS | ||||||

| 0.48 | 17.17 | 56.4059* | ||||

| X on Y | 0.72 | 0.55 | 1.31 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 1.82 |

| Total effect | 1.59 | 0.49 | 3.19 | 0.00* | 0.59 | 2.59 |

| Indirect effect of X on Y | 2.32 | 0.43 | 1.55 | 3.34 | ||

| Pain-BMI-KOS | ||||||

| 0.47 | 242.4 | 27.16* | ||||

| X on Y | 1.68 | 1.3 | 1.26 | 0.20 | 0.97 | 4.33 |

| Total effect | 4.31 | 1.64 | 2.21 | 0.01* | 1.01 | 7.61 |

| Indirect effect of X on Y | 2.63 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 5.07 | ||

BMI: body mass index; KOS: knee outcome survey. *p ≤ 0.01.

Table 5.

Effect size significance.

| Variables | Effect | SE | Z value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain-BMI-KOS | 2.63 | 1.15 | 2.28 | 0.02* |

| Girth-BMI-KOS | 2.13 | 0.48 | 4.38 | 0.00* |

BMI: body mass index; KOS: knee outcome survey; SE: Standard Error, p ≤ 0.01.

Discussion

KOS-ADL is a questionnaire that benefits from intelligible wording, making it easily understood by people with knee problems. The questionnaire is considered to be internally consistent and validated; the internal consistency results were similar to those obtained by the original American-English version (Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.92–0.93) in patients with disorders of the knee.20, 22, 23 The questionnaire is also validated by face validity and construct validity,22 validating it also for future medical research in the Middle East.

The result shows that BMI, reduced ROM, and knee girth of patients were significantly higher in the KOA group than that of the control group. This indicates that changes in these variables could lead to the development of KOA. The study indicated that age, BMI, ROM and girth have no significant correlation with KOS-ADL asymptomatic physical functioning. Studies have shown that weight loss decreases the risk of KOA. Weight loss is found to reduce the cartilage thickness, thereby increasing the ROM.35 This could be the reason why BMI and ROM show non-significant correlation with KOS-ADL physical functioning. Some pre-operative predictors of the knee outcome survey are found to be knee flexion ROM, older age,36 and higher BMI37 as contributing factors. Although obesity is connected to the development of KOA, its potential impact as a pre-operative predictor and post-operative outcome is less clear.37 In a study carried out in Sweden, BMI, waist–hip ratio, weight, and percentage of body fat have positive correlations with KOA in a longitudinal follow-up survey on discharged patients over the course of 10 years.38 Studies have identified obesity as a risk factor for KOA39 and found a correlation between the two; however, other studies have shown that a strong relationship between pre-operative and post-operative KOS-ADL and BMI is still lacking. This research shows that high BMI increases the progression of KOA and interferes with or mediates pain and knee circumference. Measuring joint volume is indispensable for physiotherapy intervention, as it quantifies the severity and the extension of the edema.13

Obesity may contribute to KOA through increased thigh circumference, inducing genu varum40; however, the effects of thigh circumference on knee joint movement have not been reported in adults.41 Studies have proved that (simulated) increased thigh girth increases knee joint compressive forces by 16%. This could be due to changes in gait dynamics associated with increased thigh volume, which can then be attributed to increased knee varus41, 42 BMI is identified as a predictor of pain and function in KOA,43 but pain intensity is also an important predictor of KOA.44 This result is in line with the present study, which found that higher pain intensity predicts worse KOS-ADL scores. Higher levels of pain, then, correlate with greater intake of calories, fat, and sugar throughout the day.45 This is significant given that 86% of the respondents in this study are overweight or obese, which explains how BMI mediates the relation between pain and girth on KOS-ADL.

A logistic regression revealed that age, KOS-ADL, quadriceps strength, and knee extension ROM significantly predicted knee arthroplasty. Using only three clinical measures (age, knee extension ROM, and KOS-ADL scores), their model explained most of the variability.37 Even so, the relationship between ROM and KOS-ADL does not demonstrate significance in bootstrapping. A study found that KOA patients have 119° as their mean ROM for conservative treatment group,46 whereas the patients in this study demonstrated a ROM of 126.48°. This could be explained by the fact that Muslim populations require higher ROM owing to their common religious and cultural activities demanding flexion of the joints in the lower limbs in order to engage in prayer.47 This study also provides a deeper understanding of the relationship between girth and ROM, which is found to be negative, suggesting that greater knee girth could be due to swelling, causing a considerable reduction in ROM. Physiotherapists generally tailor their interventions based on functional ability and not on structural findings, such as knee circumference; therefore, such understanding would enhance the effectiveness of interventions specific to treatment of this symptom, for example, rest, appropriate positioning, and elevation of the lower limb.13

The uniqueness of this study is partially attributed to the relatively overweight sample used when compared to other studies of Middle Eastern populations. An additional strength of the study is the variance of age (50.53 ± 12.706) of the experimental group compared to other studies with respondent ages of over 45 years. Both this and other studies have put forward the need for further confirming the mediating role of BMI in osteoarthritis.48 The study has therefore met the three objectives (1) has established the reliability and validity of the KOS-ADL questionnaire commonly used in evaluating the Saudi Arabian population's health. The study has elucidated the effects of age, BMI, ROM and girth on the KOS-ADL of KOA patients while comparing age and BMI with perceived knee function in healthy unrestricted individuals. This study also brings out the specific role of BMI as a mediator in influencing the relationships between these variables and KOA pain. The study has few limitations though, in particular, it is limited by a small sample size and study design.

Conclusions

The results of this study would be highly useful in managing patients and would be relevant for physical therapists carrying out physical examinations – these findings would enable them to gain a broader perspective of KOA. In comparison with the control group, higher BMI increases the chances of developing KOA considerably. This study is unique in trying to understand the predictors of KOA and elucidating the specific role of each independent variable in the knee outcome survey. Future researchers could benefit from studying BMI categories and how each category would lead to KOA.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors' contributions

KAA and SPS are responsible for the conception and design of study, acquisition and analysis of data. Along with RSR, they drafted the article and approved the final manuscript after critical revision. RSR, IA and VNK contributed towards acquisition of data and MMA rendered contribution towards analysis of data. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- 1.Lovaasen K.R., Schwerdtfeger J. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014. Icd-10-cm/pcs coding: theory and practice. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Arfaj A., Al-Boukai A. Prevalence of radiographic knee osteoarthritis in Saudi Arabia. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21(2):142–145. doi: 10.1007/s10067-002-8273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Losina E., Weinstein A.M., Reichmann W.M., Burbine S.A., Solomon D.H., Daigle M.E. Lifetime risk and age at diagnosis of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(5):703–711. doi: 10.1002/acr.21898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeser R.F. Age-related changes in the musculoskeletal system and the development of osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):371–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohamed G.A., Al-Harizi W.M., Bedewi M.A., Gafar H.H. Vitamin D deficiency in knee osteoarthritis and its relationship with obesity in Saudi Arabia. Life Sci J. 2015;12(2) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chokkhanchitchai S., Tangarunsanti T., Jaovisidha S., Nantiruj K., Janwityanujit S. The effect of religious practice on the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(1):39–44. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steultjens M., Dekker J., Van Baar M., Oostendorp R., Bijlsma J. Range of joint motion and disability in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Rheumatology. 2000;39(9):955–961. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.9.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felson D.T., Zhang Y., Hannan M.T., Naimark A., Weissman B., Aliabadi P. Risk factors for incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham study. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(4):728–733. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAlindon T., Cooper C., Kirwan J., Dieppe P. Determinants of disability in osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52(4):258–262. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.4.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amoako A.O., Pujalte G.G.A. Osteoarthritis in young, active, and athletic individuals. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;7:27. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S14386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ersoz M., Ergun S. Relationship between knee range of motion and Kellgren–Lawrence radiographic scores in knee osteoarthritis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82(2):110–115. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanghi D., Srivastava R.N., Singh A., Kumari R., Mishra R., Mishra A. The association of anthropometric measures and osteoarthritis knee in non-obese subjects: a cross sectional study. Clinics. 2011;66(2):275–279. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000200016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva A.E.L., Martimbianco A.L.C., Pontin J.C.B., Lahoz G.L., Carneiro Filho M., Chamlian T.R. Reproducibility analysis of knee circumference in individuals with osteoarthritis. Acta Fisiátr. 2014;21(2) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson J.J., Felson D.T. Factors associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in the first national Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES I) evidence for an association with overweight, race, and physical demands of work. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128(1):179–189. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coggon D., Reading I., Croft P., McLaren M., Barrett D., Cooper C. Knee osteoarthritis and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metabolic Disord. 2001;25(5) doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manninen P., Riihimaki H., Heliovaara M., Makela P. Overweight, gender and knee osteoarthritis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord J Int Assoc Study Obes. 1996 Jun;20(6):595–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reijman M., Pols H., Bergink A., Hazes J., Belo J., Lievense A. Body mass index associated with onset and progression of osteoarthritis of the knee but not of the hip: the Rotterdam study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(2):158–162. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.053538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toivanen A.T., Heliövaara M., Impivaara O., Arokoski J.P., Knekt P., Lauren H. Obesity, physically demanding work and traumatic knee injury are major risk factors for knee osteoarthritis—a population-based study with a follow-up of 22 years. Rheumatology. 2010;49(2):308–314. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teichtahl A.J., Wang Y., Wluka A.E., Cicuttini F.M. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis: new insights provided by body composition studies. Obesity. 2008;16(2):232–240. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonçalves R.S., Cabri J., Pinheiro J.P. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Portuguese version of the knee outcome survey-activities of daily living scale (KOS-ADLS) Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(11):1445–1449. doi: 10.1007/s10067-008-0996-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teeters M.L. Ohio University; 2009. Obesity and health risk factors for employees at a major university in rural appalachian Ohio. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins N.J., Misra D., Felson D.T., Crossley K.M., Roos E.M. Measures of knee function: International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee evaluation form, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Physical Function Short Form (KOOS-PS), Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADL), Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, Oxford Knee Score (OKS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Activity Rating Scale (ARS), and Tegner Activity Score (TAS) Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(S11):S208–S228. doi: 10.1002/acr.20632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irrgang J.J., Snyder-Mackler L., Wainner R.S., Fu F.H., Harner C.D. Development of a patient-reported measure of function of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(8):1132–1145. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzgerald G.K., White D.K., Piva S.R. Associations for change in physical and psychological factors and treatment response following exercise in knee osteoarthritis: an exploratory study. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(11):1673–1680. doi: 10.1002/acr.21751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes A.F. Guilford Press; 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sobel M.E. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol Methodol. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacKinnon D.P., Lockwood C.M., Hoffman J.M., West S.G., Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):83. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrout P.E., Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(4):422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards J.R., Lambert L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol Methods. 2007;12(1):1. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes A.F. 2012. PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preacher K.J., Rucker D.D., Hayes A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar Behav Res. 2007;42(1):185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jöreskog K.G., Sörbom D. Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2006. LISREL 8.80 for windows [Computer software] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ringle C., Wende S., Becker J.-M. SmartPLS GmbH; Boenningstedt: 2015. SmartPLS 3. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ringle C.M., Wende S., Becker J.-M. SmartPLS GmbH; Boenningstedt: 2015. SmartPLS 3.http://www.smartpls.com [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anandacoomarasamy A., Leibman S., Smith G., Caterson I., Giuffre B., Fransen M. Weight loss in obese people has structure-modifying effects on medial but not on lateral knee articular cartilage. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(1):26–32. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Abdulwahab S.S. The effects of aging on muscle strength and functional ability of healthy Saudi Arabian males. Ann Saudi Med. 1999;19:211–215. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1999.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeni J.A., Axe M.J., Snyder-Mackler L. Clinical predictors of elective total joint replacement in persons with end-stage knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lohmander L.S., de Verdier M.G., Rollof J., Nilsson P.M., Engström G. Incidence of severe knee and hip osteoarthritis in relation to different measures of body mass: a population-based prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(4):490–496. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.089748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang L., Tian W., Wang Y., Rong J., Bao C., Liu Y. Body mass index and susceptibility to knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(3):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kajaks T. 2008. The effect of sustained static kneeling on knee joint gait parameters. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segal N.A., Yack H.J., Khole P. Weight, rather than obesity distribution, explains peak external knee adduction moment during level gait. Am J Phys Med Rehabil Assoc Acad Physiatr. 2009;88(3):180. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318198b51b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Messier S.P., Beavers D.P., Loeser R.F., Carr J.J., Khajanchi S., Legault C. Knee-joint loading in knee osteoarthritis: influence of abdominal and thigh fat. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(9):1677. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maly M.R., Costigan P.A., Olney S.J. Determinants of self-report outcome measures in people with knee osteoarthritis. Archives Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(1):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.08.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maly M.R., Costigan P.A., Olney S.J. Self-efficacy mediates walking performance in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(10):1142–1146. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choi K.W., Somers T.J., Babyak M.A., Sikkema K.J., Blumenthal J.A., Keefe F.J. The relationship between pain and eating among overweight and obese individuals with osteoarthritis: an ecological momentary study. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(6):e159–e163. doi: 10.1155/2014/598382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee K., Yi C.-W., Lee S. The effects of kinesiology taping therapy on degenerative knee arthritis patients' pain, function, and joint range of motion. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(1):63. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ariff M., Arshad A., Johari M., Mas R.A., Fadzli A., Anuar C. The study on range of motion of hip and knee in prayer by adult Muslim males. A preliminary report. Int Med J Malays. 2015;14(1) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oyeyemi A.L. Body mass index, pain and function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Niger Med J. 2013;54(4):230. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.119610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]