Abstract

Background

Splenic nodules are uncommon entities that occur rarely in the general population. Although an infectious etiology (primarily bacteria, followed by mycobacteria) is usually found, noninfectious diseases, including malignancies and autoimmune disorders, can also be involved. For instance, in course of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), in particular Crohn’s Disease, aseptic splenic abscesses have been reported in patients with a long history of illness, or in those unresponsive to medical treatments, while are only anecdotally reported in the early phase of the disease. Hence, we presented the case of aseptic splenic nodules as a first manifestation of Crohn’s Disease.

Case presentation

A 21-year-old woman with a silent medical history was admitted to the Emergency Department of our hospital complaining of fever of 38–39 °C (mainly in the evening) for the past 10 days and left flank abdominal pain, accompanied by sweating and fatigue. An abdominal computed tomography showed multiple splenic nodules of unknown origin. Because of the absence of clinical improvement after several antibiotic therapiesand a positron emission tomography (PET) with hypercaptation strictly localized to spleen, she underwent splenectomy, in suspicion of lymphoma. For persistence of symptoms after splenectomy, she underwent many instrumental examination, including a colonoscopy with bowel and intestinal biopsies that poses diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. A second PET confirmed this diagnosis showing this time also the gastrointestinal involvement.

Conclusion

An unusual onset of Crohn’s disease with multiple splenic nodules is reported. This case suggests that in light of splenic nodules of unknown etiology attention should be paid to all possible diagnoses of aseptic abscesses, including IBDs (primarily Crohn’s Disease).

Keywords: Splenic abscesses, Crohn’s disease, Inflammatory bowel diseases

Background

Splenic nodules are rare entities that occur at a low frequency in the general population (between 0.14 and 0.7%) [1], whose etiological definition can be quite troubling since they can be observed under several different conditions although they are more frequently caused by infectious diseases (Table 1). Aerobes (gram-positive cocci and gram-negative bacilli), anaerobes (mostly Bacteroides spp. and Clostridium spp.), and fungi (Candida spp. and Aspegillus spp.) are often involved indeed, causing either monomicrobial or polymicrobial splenic abscesses [2]. In particular, gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes should be suspected in case of intra-abdominal infections; in immunocompromised hosts, however, gram-negative bacteria, fungi and mycobacteria should be considered in the differential diagnosis even independently from the infectious site [1, 2]. In addition, cases of tubercular granulomas of the spleen or secondary splenic localization of atypical disseminated mycobacteriosis are repeatedly reported in the literature [3, 4].

Table 1.

Main causes of splenic abscesses

| Main causes of splenic abscesses | |

|---|---|

| Bacterial Infections | - Gram positive bacteria (Staphilococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Clostridium spp., etc) |

| - Gram negative bacteria (Enterobacteriacee, non fermenting Gram Negative bacteria, etc) | |

| - Rare organisms (Nocardia spp., Actynomices spp., etc) | |

| Fungal Infections | - Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., Endemic Fungi, etc |

| Mycobacterial Infections | - M. tuberculosis spp., Atypical Mycobacteria spp. |

| Blood Cancers | - Lymphoma/Leukemia |

| Solid Cancers | - Metastasis |

| Auto-immune Disorders | - Reumatoid Arthritis |

| - Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | |

| - Dermato/Polymyositis | |

| - Sarcoidosis | |

| - Systemic Vasculitis (Polyarteritis Nodosa, Granulomatosis with Polyangitis, etc) | |

| - Inflammatory Bowel Diseases | |

| Genetic Diseases | - Common Variable Immunodeficiency |

| - Rare Genetic Immunodeficiency Disorder | |

Many other noninfectious diseases can also be associated with aseptic splenic abscesses: lymphoma, leukemia, and metastastatic solid tumors are other important illnesses to investigate and consider for differential diagnosis [2]. Similarly, splenic involvement could occur in course of disseminated autoimmune disorders such as common variable immunodeficiency, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) [5, 6], systemic lupus erythematosus [7], rheumatoid arthritis [8], or sarcoidosis [9]. However, in these cases, splenic abscesses emerge as late complications of disease in patients unresponsive to medical treatments, or with long history of illness. On the contrary, splenic nodules have been rarely observed in early phases of these autoimmune diseases. Thus, we presented an unexpected case of multiple splenic abscesses as an ascertained first manifestation of Crohn’s disease.

Case presentation

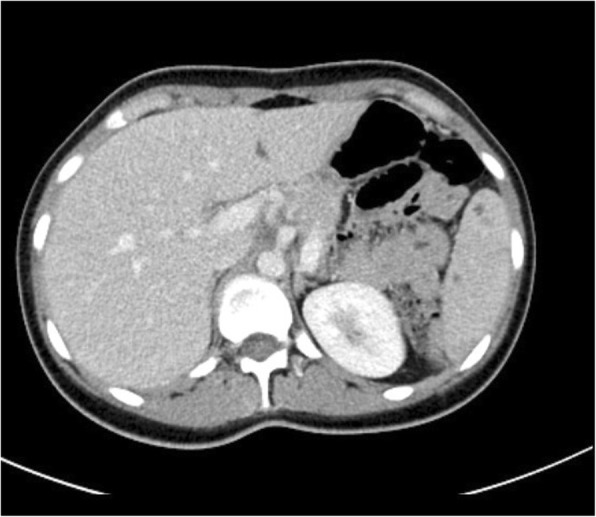

A 21-year-old woman with a silent medical history was admitted to the Emergency Department of the University Hospital of Bari (Italy), complaining of a fever of 38–39 °C (mainly in the evening) for the past 10 days and left flank abdominal pain, accompanied by sweating and fatigue. She reported no weight loss, drug consumption, or traumatic events. Blood exams showed leukocytosis (16.62 × 103/μL), elevated platelets (506 × 103/μL), ESR (99 mm/h), CRP (131 mg/L), and PCT (0.10 ng/mL), while abdominal CT scan (Fig. 1) revealed celiac-mesenteric lymphoadenopathy, splenomegaly and the presence of multiple anechoic hypoechogenic nodules of unknown origin. Therefore, she was admitted to our Infectious Diseases Unit for further investigations.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal CT scan. The CT scan shows multiple anechoic hypoechogenic nodules of the spleen, suggestive of abscesses or splenic lymphoma

Based on the most common etiologies, many laboratory investigations were done, beginning with microbiological exams: blood cultures, urine cultures, copro-cultures, Mantoux test and Quantiferon TB Gold, serologies for viruses (HIV, HCV, HBV, CMV, EBV, HSV 1/2, and VZV), Toxoplasma spp., Amoeba spp., Echinococcus spp., and Leishmania, and immunoglobulins and tumor markers dosage.

Because of her persistent fever and elevated inflammatory markers, the patient commenced empirical antibiotic therapy with Piperacillin/Tazobactam and Gentamicin.

However, all aforesaid investigations and both transthoracic echocardiography and abdominal ultrasonography were negative, while inflammatory markers remained elevated (CRP 120 mg/L, ESR 120 mm/h, CBC 12.23 × 103/μL), and her fever slightly decreased although it did not resolve despite 10 days of antibiotics, which were therefore discontinued, due to ineffectiveness.

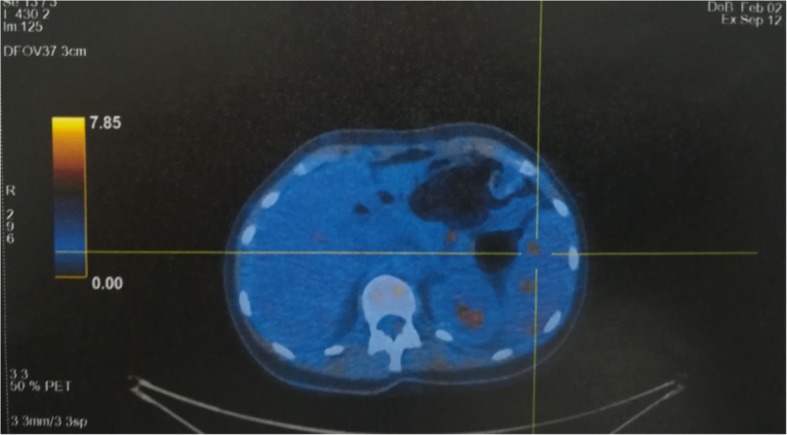

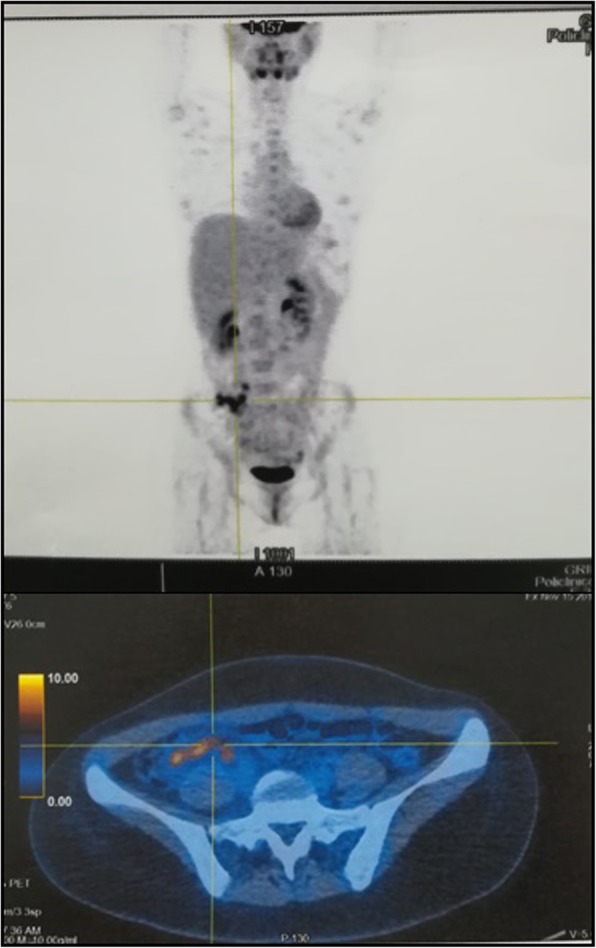

Owing the high suspicion of splenic neoplastic localization, the patient underwent a PET (Fig. 2) that showed a pathologic hypercaptation strictly localized to splenic nodules and retroperitoneal lymph nodes, strengthening the diagnostic hypothesis of lymphoma. Therefore, after consultation with a hematology specialist and a general surgeon, the patient underwent splenectomy and then was discharged, to wait at home for the histological results.

Fig. 2.

CT/PET Total Body CT/PET Total Body shows hypercaptation of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in the spleen

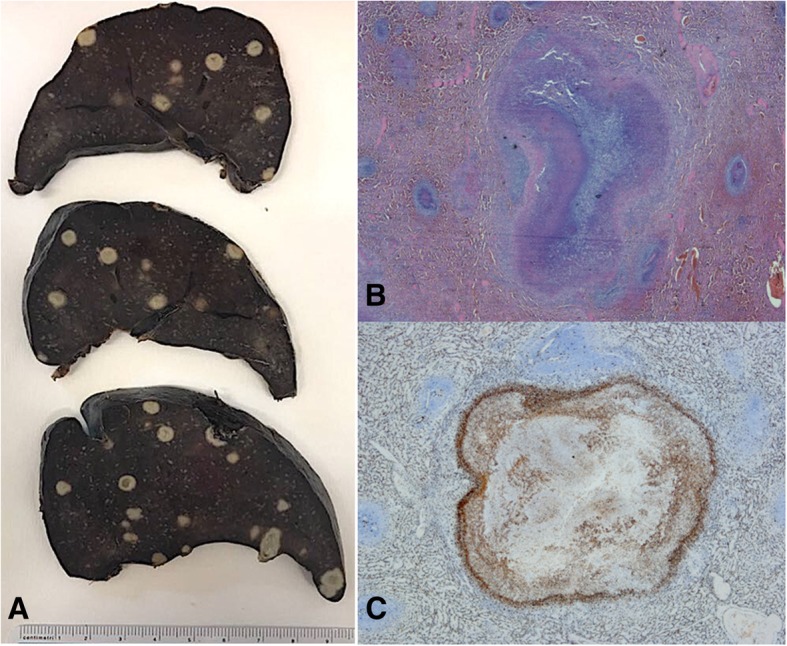

Macroscopic examination of the splenic cut surface showed many nonconfluent white nodules (Fig. 3, panel a). Histologically, spleen nodules showed numerous areas of necrosis (composed of neutrophils and cellular debris) surrounded by an organized epithelioid macrophage reaction (Fig. 3, panel b), displaying CD68 immunoreactivity (Fig. 3, panel c). An extensive immunohistochemical study excluded a primitive splenic lymphoma.

Fig. 3.

Splenic histology. Panel a: Macroscopic examination of the spleen. Panel b: Microscopic examination of a spleen nodule showing areas of necrosis surrounded by an organized epithelioid macrophage reaction (original magnification × 20). Panel c: Microscopic examination of a spleen nodule displaying CD68 immunoreactivity confirming the presence of activated monocyte/macrophage cells surrounding the necrosis area (original magnification × 20)

The PAS, PAS diastase, Ziehl-Neelsen, and Grocott stains demonstrated the absence of fungal and mycobacterium organisms, suggesting a bacterial necrotizing process. However, all microbiology investigations on the spleen samples were negative.

Three weeks after the splenectomy, the patient was readmitted with persistent mild grade fever (38 °C) and general malaise. Additional blood samples were collected to test for Brucella, Bartonella, Yersinia spp., Campylobacter spp., Coxiella, Trichinella spp., and Shigella spp., and stools samples were obtained to perform DNA PCR for Yersinia spp., Campylobacter spp., Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., E. coli (EIEC, STEC/VTEC), and Clostridium difficile. The laboratory investigations were completed by assessing neutrophil activity, Burst Test and Angiotensin Converting Enzyme dosage; anyway, all requested tests were negative.

Concurrently, a new antibiotic empiric cycle was started with Piperacillin/Tazobactam and Vacomycin. During hospitalization, the patient became afebrile, but leukocytosis (15.56 × 103/uL) and inflammatory markers (ESR 120 mm/h, CRP 54 mg/L) remained elevated. An ex-juvantibus anti-mycobacterial therapy with Isoniazid, Rifampicin, Etambutol and Clarithromycin, in suspect of disseminated atypical mycobacteriosis, was then attempted.

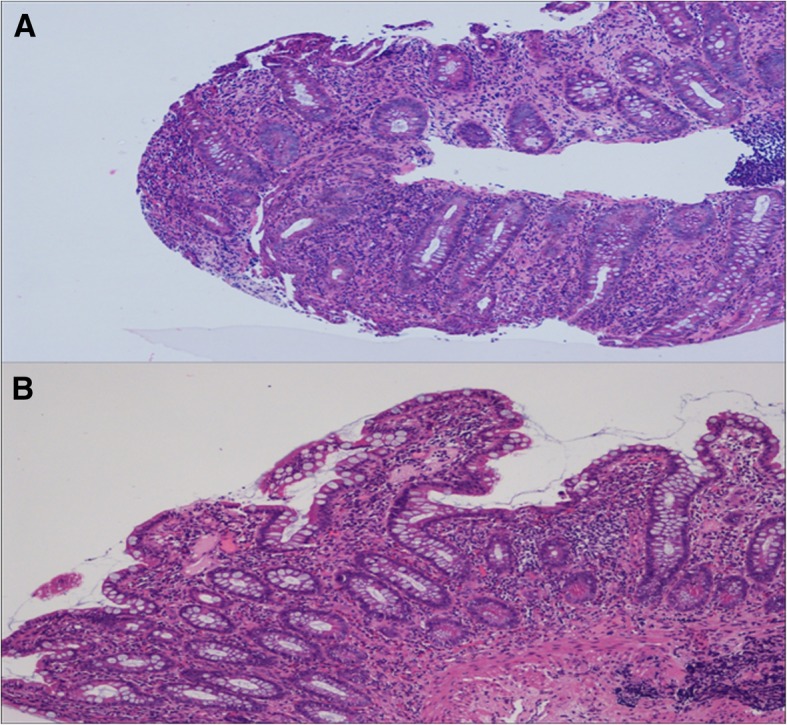

Moreover, trans-esophageal echocardiography (TEE) and gastroscopy were performed, but the results were negative for both. Finally, the patient underwent a colonoscopy with evidence of multiple superficial mucosal ulcerations of the descending colon and rectal sparing. Histological examination revealed aphthous erosions characterized by focal surface epithelial necrosis associated with mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate, foci of glandular distortion and the absence of granulomas, all of which are consistent with Crohn’s disease (Fig. 4). Concomitantly, we received the results of auto-antibodies assessment, performed during the previous hospitalization, that resulted negative, apart from positive ASCA IgG results.

Fig. 4.

Histological examination of the gut. Microscopy of the descending colon (a) and ileum (b) showing chronic inflammatory infiltrate, glandular distortion and aphthous erosions, all highly suggestive of Crohn’s disease (hematoxilin and eosin, original magnification × 100)

The patient also underwent a new PET displaying an unexpected, newly onset pathological capture in the lower gastrointestinal tract that was not evident in the previous PET (Fig. 5). Hence, after almost three months of investigations, a diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease was made on the basis of colon biopsies, positive ASCA IgG results and considering that splenic nodules are possible complications of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBDs), even if this very rare complication generally occurs in the later stages of the disease.

Fig. 5.

Second CT/PET Total Body. The second CT/PET shows 18F-DFG accumulation only in the descending colon

The diagnosis was also made on the basis of anecdotical cases in the literature showing that splenic nodules can arise simultaneously with colonic manifestations or even precede gastrointestinal involvement.

In conjunction with the gastroenterology specialists, the anti-mycobaterial treatment was discontinued and she commenced corticosteroids and mesalazin. After one week, her blood tests showed a substantial reduction of inflammatory markers (CRP 17.6 mg/L and ESR 110 mm/h), and she was discharged at home in good clinical condition with a diagnosis of extraenteric manifestations of Crohn’s disease.

Discussion and conclusions

Splenic abscesses are a rare and ambiguous clinical entity associated with a wide range of diseases. Differential diagnosis is often problematic, particularly if there are no other particular signs or symptoms that can direct the diagnostic workup. Given this wide variety of alternative possibilities, patients affected by splenic nodules of unknown origin often require long hospitalization, a deep anamnesis, and a wide range of laboratory tests, including the assessment of autoimmune diseases [6–9] and microbiological investigations to exclude infections caused by bacteria, fungi and mycobacteria [2–4]. Among autoimmune diseases, the onset of Crohn’s Disease as splenic abscesses is very rare. In fact, Crohn’s Disease may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus [10] but can also cause many different extra-enteric manifestations either at earlier or later disease phases. Among the wide range of manifestations, musculoskeletal and dermatologic systems are the most commonly affected, although the involvement of the hepato-pancreato-biliary system (e.g., primary sclerosing cholangitis) and the ocular, renal, and pulmonary systems have also been described [11, 12]. Albeit Crohn’s extra-intestinal aseptic abscesses are well known and often described, in a literature search of the PUBMED database, only three papers reporting single cases of splenic abscesses as a first manifestation of disease, before the onset of clinically evident gastrointestinal manifestations were found [13–15]. In addition, a fourth paper from the “French Study Group on Aseptic Abscesses” describes 21 cases of aseptic splenic abscesses associated with IBDs, including 7 cases arisen before an IBD diagnosis was formulated [5].

Notably, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time in the medical literature that the onset of splenic abscesses prior to gastroenteric manifestation of Crohn’s Disease is demonstrated with PET. In fact, the execution of two PETs at a one-month interval allowed us to effectively demonstrate that the splenic involvement preceded the onset of intestinal lesions.

In conclusion, an unusual onset of Crohn’s disease with multiple splenic nodules is reported. This case documents Crohn’s disease as a rare cause of aspetic splenic abscess, that should be considered among possible differential diagnosis of this ambiguos clinical entity.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ASCA

anti-saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- CRP

C reactive protein

- CT scan

Computed tomography scan

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- EIEC

Entero-invasive E. coli

- ESR

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HSV

Herpes virus

- IBDs

Inflammatory bowel diseases

- PAS

Periodic acid-schiff

- PCT

Procalcitonin

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- STEC

Shiga toxin-producing E. coli

- TB

Tuberculosis

- TEE

Trans-esophageal echocardiography

- VTEC

Vero-toxin E.coli

- VZV

Varicella-Zoster virus

Authors’ contributions

SA and BDF suspected the diagnosis and were the major contributor in writing the manuscript. IG and FF performed the histological examination of spleen and colon biopsy. AG, SF and DGF contributed in clinical management of patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study did not require a formal approval from the ethics committee according to the Italian law since it was performed as an observational research in the context of normal clinical routines (article 1, Legislative Decree 211/2003). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national and institutional standards.

The patient provided an informed written consent for the anonymous collection and use of her data for research purposes.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the patient, who signed our institutional consent form, that is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

D. F. Bavaro, Phone: +39 080 5592477, Email: davidebavaro@gmail.com

G. Ingravallo, Email: giuseppe.ingravallo@uniba.it

F. Signorile, Email: fabiosignorile@yahoo.it

F. Fortarezza, Email: francescofortarezza.md@gmail.com

F. Di Gennaro, Email: cicciodigennaro@yahoo.it

G. Angarano, Email: gioacchino.angarano@uniba.it

A. Saracino, Email: annalisa.saracino@uniba.it

References

- 1.Ferraiolia G, Brunettia E, Gulizia R, et al. Management of splenic abscess: report on 16 cases from a single center. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(4):524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyrniotis V, Kehagias D, Voros Fotopoulos D, et al. Splenic abscess. An old disease with new interest. Dig Surg. 2000;17(4):354–357. doi: 10.1159/000018878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fooladi AA, Hosseini MJ, Azizi T. Splenic tuberculosis: a case report. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(5):e273–e275. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theotokatou S, Doulgerakis S, Kallinikos A. Multiple mycobacterial splenic abscesses and skin involvement, in an immunocompetent person. Hellenic J Surg. 2011;83:290. doi: 10.1007/s13126-011-0053-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andre MF, Piette JC, Kemeny JL, et al. Aseptic abscesses: a study of 30 patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86(3):145–161. doi: 10.1097/md.0b013e18064f9f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timmermans WMC, van Laar JAM, van Hagen PM, et al. Immunopathogenesis of granulomas in chronic autoinflammatory diseases. Clin Transl Immunology. 2016;5(12):e118. doi: 10.1038/cti.2016.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bharti A, Meena LP. Systemic lupus erythematosus with hepatosplenic granuloma: a rare case. Case Reports Immunol. 2014;2014:737453. doi: 10.1155/2014/737453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamio N, Kuramochi S, Wang RJ, Hirose S, Hosoda Y. Rheumatoid arthritis complicated by pachy- and leptomeningeal rheumatoid nodule-like granulomas and systemic vasculitis. Pathol Int. 1996;46(7):526–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1996.tb03649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neiman RS. Incidence and importance of splenic sarcoid-like granulomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1977;101(10):518–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Sandborn. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1590–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, et al. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1116–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7(4):235–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García López S, Gomollón F, Gracia M. Síndrome febril y abscesos esplénicos como manifestación inicial de Enfermedad de Crohn. Monográficos Infliximab Diciembre. 2008;1.

- 14.André M, Aumaître O, Papo T, et al. Disseminated aseptic abscesses associated with Crohn's disease. A new entity? Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:420–428. doi: 10.1023/A:1018835228850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calzado S, Navarro M, Puig I, et al. Splenic abscess as the first manifestation of Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(6):703–704. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.