Abstract

Background

An association between visual impairment and cognitive outcomes has been documented, but there is limited research examining this relationship using multiple measures of vision.

Methods

Participants included non-demented individuals in Year 3 of the Visual impairment was assessed using visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity. Cognitive function was defined using the digit symbol test and the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS). Incident cognitive impairment was defined as a 3MS score <80 or a decline >5 points following Year 3. Linear mixed effects models examined longitudinal associations adjusting for year, age, sex, race, education, smoking, depression, diabetes, study site, as well as interaction terms between the vision parameters and years in study, between baseline age and years in study, and quadratic terms of baseline age and years in study. Discrete Cox regression models examined the risk of incident cognitive impairment.

Results

Analyses included 2,444 participants (mean age = 74). Visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity impairments were not associated with statistically significant changes in annual digit symbol test scores over 7 years of follow-up, as compared to those without these impairments. However, visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity impairments were associated with greater declines in annual 3MS scores over 9 years. Participants with impaired visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity had a greater risk of incident cognitive impairment.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity impairments may be risk factors for cognitive decline.

Keywords: Cognition, Cognitive aging, Brain aging, Visual impairment

Visual impairment is an important aspect of aging for many older adults. In 2010, there were approximately 186 million adults aged ≥50 years with visual impairment worldwide (1). In the United States, >3 million adults aged ≥40 years have visual impairments uncorrectable by glasses or contact lenses, and this estimate is expected to increase to 7 million by 2050 (2). As the number of adults with non-correctable visual impairment increases, research at the intersection of geriatrics and eye care has prioritized understanding and improving functioning and health in older adults with visual impairments.

Over the past decade, this research has expanded to include studies examining the association between visual impairment and cognitive function (3–6). However, much of this research has been cross-sectional and primarily focused on the association between reduced distance visual acuity and cognitive impairment (3–6). Results indicate that older adults with impaired visual acuity have a twofold increased risk of cognitive decline (7, 8), indicating that visual impairment is an important risk factor for cognitive decline. However, vision is a complex process, and visual acuity is just one of many measures of vision. Recent research indicates that other measures of vision, such as reduced contrast sensitivity, are also risk factors for cognitive decline (8, 9). These results suggest that measures of visual function beyond visual acuity may be needed to fully understand the relationship between visual impairment and cognitive function in older adults.

We examined the longitudinal association between three measures of visual function—visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity—with cognitive decline, and incident cognitive impairment in older adults, using data from the Health Aging, and Body Composition (ABC) study.

Methods

Study Population

The Health ABC study is a prospective cohort of 3,075 community-dwelling, high physical–functioning older adults aged 70–79 years at enrollment and resided in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, or Memphis, Tennessee. Participants were selected from a random sample of white Medicare beneficiaries and all age-eligible black community residents. Baseline study visits occurred from 1997 to 1998, and participants were followed up annually for up to 16 additional years (10). Enrollment and eligibility criteria have been previously described (11), and required (a) no reported difficulty walking ¼ mile, walking up 10 steps, or performing activities of daily living; (b) no known life-threatening cancers; and (c) no plans to move out of the study area for 3 years. Participants provided informed consent and the institutional review boards at each study site approved all protocols.

Analytic Sample

For this study, visual function and cognition measures were assessed using standard protocols at each study site. Vision was measured only in Year 3 (1999–2000), which served as the baseline assessment for these analyses. Cognitive function was assessed in Year 3 and up to nine subsequent years of follow-up. A total of 2,921 participants completed the Year 3 exam, but cross-sectional analyses were limited to 2,444 participants who underwent visual testing, did not have dementia in Year 3, and had cognitive testing data. Among these participants, missing covariate data ranged from 0% to 2.8% for the sample. As these percentages are relatively low, complete case analyses were used by removing the observations with missing values from cross-sectional models (sample sizes shown in tables). In longitudinal analyses, out of the 2,424 participants with Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) scores and information for all the covariates, 673 (27.8%) were lost to follow-up after Year 3, and for the 2,121 participants in the longitudinal digit symbol test analyses, 699 (33%) were lost to follow-up after Year 5.

Vision Assessments

Vision measures were assessed at the Year 3 study, as previously described (12). Presenting visual acuity was measured using high contrast Bailey–Lovie chart (13, 14) and contrast sensitivity was measured using a Pelli–Robson chart (15, 16). Both tests were administered at a 10 or 5 feet testing distance with participants wearing habitual corrective lenses (if applicable) and the total number of letters read correctly was recorded from each chart. Visual acuity was calculated in logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution units. Contrast sensitivity was calculated as logContrast units, which indicates the lowest contrast threshold discerned, and ranges from 0 to 2.25 logContrast units where higher values indicate better contrast sensitivity. Stereo acuity, which is a measure of depth perception, was measured with the Frisby stereo test (17) at 40–80 cm testing distance. Participants were presented with stereo images of decreasing depth differentials over three trials (340, 170, and 85 seconds of arc). The smallest depth disparity that was correctly discerned was recorded as the stereo acuity value.

Visual impairment status for the three measures was defined as follows: (a) visual acuity worse than 20/40 in the better eye, (b) contrast sensitivity <1.55 log contrast units, and (c) stereo acuity >85 seconds of arc (arcsec). The visual acuity impairment cutoff was chosen based on clinically meaningful criteria and is commonly used to define impairment in research studies (18–20). Contrast sensitivity impairment was defined as 2 standard deviation (SD) below the average in adults aged ≥60 years (21) and stereo acuity impairment as the inability to ascertain the smallest depth differential presented (12).

Cognitive Assessments

The measures of cognitive function were the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (22) and the 3MS (23). The digit symbol test was administered in Years 1, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 and primarily assesses psychomotor speed and executive function. Participants are required to code a series of numbers with corresponding symbols and scored as the total number correctly coded within 90 seconds. The 3MS was administered in Years 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, and 11. This global test of cognitive function includes tests of orientation, registration, recall, attention, calculation, and visual–spatial skills, and the maximum score is 100 but cognitive impairment is defined as scores <80. Participants were excluded from cognitive testing if they were unable to read large print text. Scores of 3MS were prorated for individuals who could not complete components of this test due to physical limitations, including visual impairment.

Incident cognitive impairment was defined as a 3MS score <80 or a decline in 3MS >5 points following Year 3, similar to methods used previously (24–27).

Other Covariates

Sociodemographic details including age, sex, race (white or black), and education (<high school, high school, or >high school) were recorded from Year 3 (baseline) data. Smoking status (current, former, or never smoker), diabetes (yes or no), hypertension (yes or no), and stroke (yes or no) were determined by self-report at Year 1. Depression was also determined at Year 1 and defined as a score >16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale short form (CES-D10) (28).

Statistical Analyses

Each category of visual impairment was compared across key predictors, including age, sex, race, education, smoking status, and comorbidities. In all regression analyses, vision variables were treated as baseline time-fixed predictors of the cognitive outcomes. Multiple linear regression analysis with robust standard errors was used to examine the association between the vision variables and digit symbol test scores at Year 5, adjusting for age, sex, race, education, smoking, depression, diabetes, study site. Similar regression models were built using the 3MS scores at Year 3 as the dependent variable.

Multilevel linear mixed effects regression models were used to examine the association between the vision variables and rates of change in digit symbol test and 3MS. All longitudinal analyses of digit symbol test data were from Years 5–11 (as participants were not given the digit symbol test at Year 3), a 7 years’ follow-up period, and analyses of 3MS were from Years 3–11, a 9 years’ follow-up period. A random intercept was included to account for intraparticipant correlation and a random slope was included to allow for different variance components in the Participants with respect to the rate of change. In addition, unstructured variance–covariance structure was used, allowing for the correlation between the random slope and intercept. Covariates in the models included years since the baseline visit; baseline age, sex, race, education, smoking, depression, diabetes, study site; an interaction term between the vision parameters and years in study; interaction terms between baseline age and years in study; and the quadratic terms of baseline age and years in study.

To examine how the vision variables affect time of the progression to cognitive impairment over 9 years of follow-up, the log-rank tests for equality of survivor functions were used, as well as the discrete Cox regression models, adjusting for the same covariates in the aforementioned models, and using the Breslow method to handle ties in the data. The proportional hazard assumption was checked and met for visual acuity and stereo acuity models; however, this assumption was not met for contrast sensitivity (p value for the global test of proportional hazards was .06, .05, and .01, respectively) . We further investigated the contrast sensitivity model by allowing the proportionality of hazards can change over time (results not shown).

Statistical significance was defined at p < .05. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 14.2, software (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

Results

Population Characteristics

At Year 3, the 2,444 Health ABC participants included in this study had a mean age of 74.0 years (SD: 2.8). The majority of participants were female (52.2%) and white (61.6%). Of the total baseline study population, 4.5% were classified as having visual acuity impairment, 29.5% had contrast sensitivity impairment, and 30.5% had stereo acuity impairment. Participants with visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity impairments were older, and more likely to be black, have less than a high school education, and have diabetes as compared to participants without these impairments, respectively (p < .05 for all; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics: Health Aging, and Body Composition Study Year 3 (1999–2000)†

| Total Population N = 2,444 | VA Impairment (< 20/40) 109 (4.5%) | No VA Impairment (≥20/40) 2,332 (95.3%) | p value | CS Impairment (<1.55 Log Unit) 721 (29.5%) | No CS Impairment (≥1.55 Log Unit) 1,721 (70.5%) | p value | SA Impairment (>85 arcsec) 726 (30.5%) | No SA Impairment (≤85 arcsec) 1,651 (69.5%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 74.0 (2.8) | 75.1 (3.0) | 74.0 (2.8) | <.001 | 74.9 (2.9) | 73.7 (2.7) | <.001 | 74.6 (3.0) | 73.8 (2.7) | <.001 |

| Sex, N (%) | ||||||||||

| Female | 1,275 (52.2) | 50 (45.9) | 1,224 (52.5) | .18 | 375 (52.0) | 900 (52.3) | .90 | 337 (46.4) | 909 (55.1) | <.001 |

| Male | 1,169 (47.8) | 59 (54.1) | 1,108 (47.5) | 346 (48.0) | 821 (47.7) | 389 (53.6) | 742 (44.9) | |||

| Race, N (%) | ||||||||||

| White | 1,506 (61.6) | 51 (46.8) | 1,454 (62.3) | .001 | 376 (52.1) | 1,129 (65.6) | <.001 | 410 (56.5) | 1,051 (63.7) | <.001 |

| Black | 938 (38.4) | 58 (53.2) | 878 (37.7) | 345 (47.9) | 592 (34.4) | 316 (43.5) | 600 (36.3) | |||

| Education, N (%) | ||||||||||

| <High school | 551 (22.6) | 40 (36.7) | 508 (21.8) | <.001 | 219 (30.5) | 330 (19.2) | <.001 | 200 (27.5) | 336 (20.4) | <.001 |

| High school | 806 (33.0) | 34 (31.2) | 772 (33.2) | 207 (28.8) | 599 (34.9) | 238 (32.8) | 553 (33.6) | |||

| >High school | 1,082 (44.4) | 35 (32.1) | 1,047 (45.0) | 293 (40.8) | 789 (45.9) | 288 (39.7) | 758 (46.0) | |||

| Health measures | ||||||||||

| Depressive symptoms, N (%)‡ | 107 (4.4) | 9 (8.3) | 98 (4.2) | .045 | 40 (5.6) | 67 (3.9) | .064 | 40 (5.5) | 63 (3.8) | .064 |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 550 (22.5) | 39 (35.8) | 510 (21.9) | <.001 | 223 (30.9) | 327 (19.0) | <.001 | 204 (28.1) | 331 (20.0) | <.001 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 1,471 (60.2) | 69 (63.3) | 1,401 (60.1) | .50 | 457 (63.4) | 1,014 (58.9) | .04 | 449 (61.8) | 980 (59.4) | .25 |

| Stroke, N (%) | 185 (7.6) | 11 (10.4) | 174 (7.5) | .28 | 65 (9.1) | 120 (7.0) | .080 | 63 (8.8) | 116 (7.1) | .14 |

| Smoking, N (%) | ||||||||||

| Current | 217 (8.9) | 16 (14.7) | 200 (8.6) | .088 | 82 (11.4) | 134 (7.8) | .017 | 76 (10.5) | 135 (8.2) | .15 |

| Former | 1,116 (45.7) | 48 (44.0) | 1,067 (45.8) | 323 (44.9) | 792 (46.1) | 331 (45.7) | 747 (45.3) | |||

| Never | 1,108 (45.4) | 45 (41.3) | 1,062 (45.6) | 315 (43.8) | 793 (46.1) | 318 (43.9) | 767 (46.5) | |||

| Visual functioning measures | ||||||||||

| VA (logMAR), mean (SD) | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.1) | <.001 | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.1) | <.001 | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.1) | <.001 |

| CS (logUnit), mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.1) | <.001 | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.1) | <.001 | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.1) | <.001 |

| SA impaired, N (%) | 723 (30.5) | 69 (67.7) | 654 (28.8) | <.001 | 362 (52.0) | 362 (21.6) | <.001 | 726 (30.5) | 1,651 (69.5) | <.001 |

Note: p < .05 in bold font. CI = confidence interval; CS = contrast sensitivity; logMAR = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; SA = stereo acuity; SD = standard deviation; VA = visual acuity.

†Values are expressed as number (%) unless indicated.

‡Center for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale short form score ≥16.

Baseline Cognitive Scores

In fully adjusted cross-sectional models, the relationship between visual acuity impairment and 3MS scores at Year 3 did not reach statistical significance (p = .06), but visual acuity impairment was significantly associated with lower digit symbol test scores at Year 5 (p < .001, digit symbol test was not administered at Year 3; Table 2). In separate models, contrast sensitivity and stereo acuity impairment were associated with lower 3MS scores at Year 3 and lower digit symbol test scores at Year 5 (p < .001 for all). When evaluated on a continuous scale, worse visual acuity and contrast sensitivity were associated with worse 3MS scores at Year 3 and worse digit symbol test scores at Year 5 (p < .001 for all).

Table 2.

Visual Impairment and Baseline Cognitive Test Scores: Health Aging, and Body Composition Study Year 3 (1999–2000)†

| Digit Symbol Substitution Test | Interval | N | Estimate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical vision impairment | ||||

| VA impairment | vs No VA impairment | 2,052 | −4.88 | −7.15, −2.61 |

| CS impairment | vs No CS impairment | 2,052 | −3.79 | −4.95, −2.64 |

| SA impairment | vs No SA impairment | 1,994 | −3.02 | −4.11, −1.92 |

| Continuous vision measures | ||||

| VA | 0.1 logMAR worse | 2,052 | −1.13 | −1.46, −0.8 |

| CS | 0.1 log units worse | 2,052 | −1.23 | −1.51, −0.95 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | Interval | Estimate | 95% CI | |

| Categorical vision impairment | ||||

| VA impairment | vs No VA impairment | 2,421 | −1.66 | −3.41, 0.09 |

| CS impairment | vs No CS impairment | 2,422 | −2.23 | −2.88, −1.59 |

| SA impairment | vs No SA impairment | 2,358 | −1.38 | −1.99, −0.77 |

| Continuous vision measures | ||||

| VA | 0.1 logMAR worse | 2,421 | −0.40 | −0.60, −0.20 |

| CS | 0.1 log units worse | 2,422 | −0.54 | −0.73, −0.35 |

Note: p < .05 in bold font. CI = confidence interval; CS = contrast sensitivity; logMAR = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; SA = stereo acuity; VA = visual acuity.

†Adjusted for age, quadratic term of age, sex, race, education, smoking, depression, diabetes, and study site.

Annual Change in Cognitive Scores

In fully adjusted longitudinal regression models, participants with visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity impairments did not have statistically significant declines (p > .05 for all) in annual digit symbol test scores from 1999 to 2008, as compared to those without these impairments, respectively (Table 3 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). However, visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity impairments were associated with greater declines in annual 3MS scores, as compared to those without impairments (p < .001 for all). In analyses with visual measures evaluated on a continuous scale, neither contrast sensitivity nor visual acuity was associated with change in digit symbol score (p > .05). For 3MS, contrast sensitivity was associated with annual declines over the follow-up period (p < .001), but the association with visual acuity did not reach statistical significance (p = .05).

Table 3.

Visual Impairment and Annual Rate of Cognitive Change: Health Aging, and Body Composition Study†

| Digit Symbol Substitution Test Over 7 Years of Follow-up (2001–2008) | Interval | N | Estimate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical vision impairment | ||||

| VA impairment | vs No VA impairment | 2,120 | −0.24 | −0.72, 0.24 |

| CS impairment | vs No CS impairment | 2,120 | −0.11 | −0.30, 0.09 |

| SA impairment | vs No SA impairment | 2,061 | −0.08 | −0.27, 0.10 |

| Continuous vision measures | ||||

| VA | 0.1 logMAR worse | 2,120 | −0.01 | −0.07 0.05 |

| CS | 0.1 log units worse | 2,120 | −0.04 | −0.09, 0.01 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination over 9 years of follow-up (1999–2008) | ||||

| Categorical vision impairment | ||||

| VA impairment | vs No VA impairment | 2,421 | −0.33 | −0.61, −0.06 |

| CS impairment | vs No CS impairment | 2,422 | −0.17 | −0.29, −0.05 |

| SA impairment | vs No SA impairment | 2,358 | −0.15 | −0.27, −0.03 |

| Continuous vision measures | ||||

| VA | 0.1 logMAR worse | 2,421 | −0.03 | −0.07, 0.00 |

| CS | 0.1 log units worse | 2,422 | −0.06 | −0.09, −0.03 |

Note: p < .05 in bold font. CI = confidence interval; CS = contrast sensitivity; logMAR = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; SA = stereo acuity; VA = visual acuity.

†Adjusted for year, age, sex, race, education, smoking, depression, diabetes, study site, interaction term between the vision parameters and years in study, interaction terms between baseline age and years in study, and the quadratic terms of baseline age and years in study.

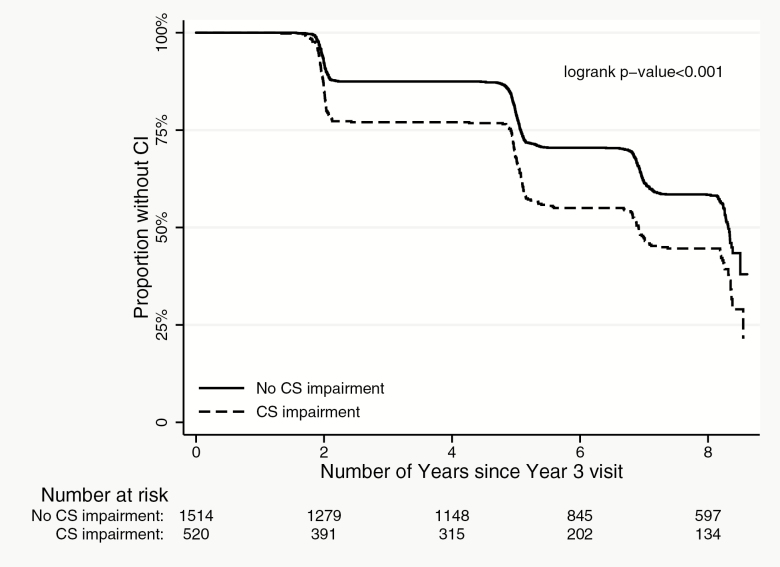

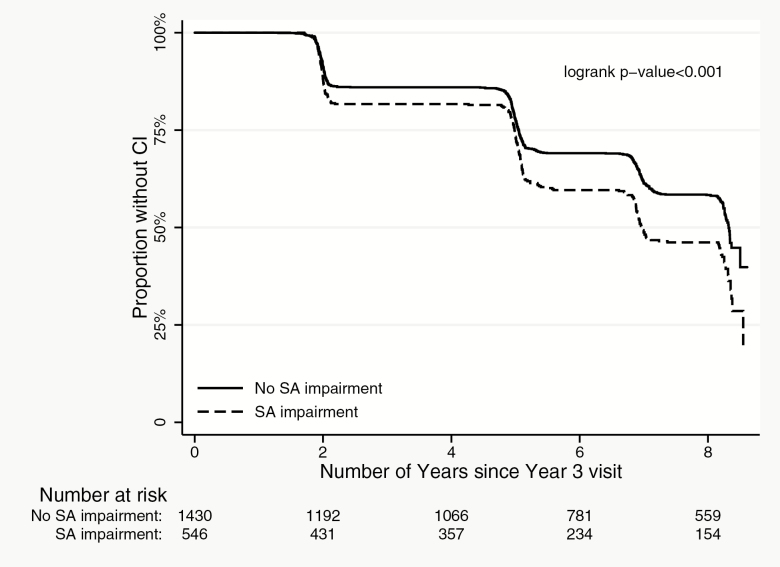

Incident Cognitive Impairment

In discrete Cox regression models, participants with visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity impairments had a greater risk of incident cognitive impairment as compared to those without these impairments, respectively (Table 4, Supplementary Table 3, Figures 1–3; p < .01 for all). Worse visual acuity and worse contrast sensitivity were also associated with increased risk of incident cognitive impairment (p < .001 for both). Our analyses of treating contrast sensitivity as a time-varying covariate in the Cox regression model also found that the effect was more prominent between Year 3 and Year 5 and diminishes afterward.

Table 4.

Visual Impairment and Incident Cognitive Impairment Over 9 Years of Follow-up: Health Aging, and Body Composition Study (1999–2008)†

| Cognitive Impairment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vision Parameters | Interval | N | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI |

| VA impairment | vs No VA impairment | 2,034 | 1.55 | 1.12, 2.14 |

| CS impairment | vs No CS impairment | 2,034 | 1.33 | 1.13, 1.55 |

| SA impairment | vs No SA impairment | 1,976 | 1.28 | 1.09, 1.49 |

| VA | 0.1 logMAR worse | 2,034 | 1.07 | 1.03, 1.12 |

| CS | 0.1 log units worse | 2,034 | 1.09 | 1.05, 1.13 |

Note: p < .05 in bold font. CI = confidence interval; CS = contrast sensitivity; logMAR = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; SA = stereo acuity; VA = visual acuity.

†Adjusted for year, age, sex, race, depression, diabetes, education, smoking, and study site.

Figure 1.

Incident cognitive impairment by visual acuity (VA) impairment status.

Figure 2.

Incident cognitive impairment by contrast sensitivity (CS) impairment status.

Figure 3.

Incident cognitive impairment by stereo acuity (SA) impairment status.

Discussion

This study suggests that older adults with visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity impairments are more likely to have declines in 3MS scores, as well as are at increased risk of cognitive impairment than those without these impairments over 9 years of follow-up. These results highlight that visual impairment is a risk factor for cognitive decline, and support the need to include measures of vision beyond visual acuity to better understand the relationship between visual impairment and cognitive outcomes.

Our results largely reflect findings from prior studies, indicating that worse vision is associated with worse 3MS scores in cross-sectional analyses and greater decline in these scores over follow-up (3, 4, 29, 30). The only exception was the cross-sectional relationship between visual acuity impairment and worse 3MS scores, which was just beyond our a priori cut point of statistical significance (p = .06). In the Health ABC Study, 3MS scores are prorated for individuals who cannot complete all sections of this test, including due to visual impairment. In addition, participants were excluded from cognitive testing as per the Health ABC protocol if they had difficulty seeing large print, which would preferentially exclude individuals with the most severe visual impairments from these analyses. Therefore, our results are likely to be conservative, particularly for cross-sectional relationships, as most participants who had difficulty seeing the cognitive tests were either excluded or accounted for in the test scoring. This limitation highlights the importance of previous research efforts to develop cognitive tests for older adults with sensory impairments (31–33).

We also found that all measures of vision were associated with worse digit symbol test scores in cross-sectional analyses, but not change in these scores in our longitudinal analyses. Our cross-sectional findings are comparable to results from analyses using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which found that visual acuity impairment was associated with worse digit symbol test scores (34). However, the lack of an association between vision measures and change in digit symbol scores may reflect the fact that the digit symbol test is a highly visual test. Unlike the 3MS, there is no adjustment in scoring of the digit symbol test for visual impairment. Therefore, the cross-sectional relationships observed cannot disentangle the inability to see the digit symbol test from a true relationship between visual impairment and the cognitive function being assessed. The lack of an association between visual impairment and decline in digit symbol test could also reflect a floor effect limiting the change in digit symbol scores, or could indicate that the 3MS is assessing cognitive domains that are more vulnerable to vision impairment than the digit symbol test. Further research is needed to determine if this invariance to decline is driven by visual impairment or other factors, as well as examine the relationship between visual impairment and individual cognitive domains.

Results from this study contribute information about the mechanism underlying the association between visual and cognitive function. Multiple mechanisms have been hypothesized to explain the sensory–cognitive relationship, including (a) that sensory and cognitive decline are the result of common causes or factors (35–37), (b) that sensory impairments are consequences of cognitive decline, or (c) that there are downstream consequences of sensory impairment that lead to cognitive decline. Results from our analyses indicate that visual impairment is a risk factor for cognitive decline, and expand on analyses from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, which reported that older adults with visual acuity impairment have a twofold increase in the risk of cognitive impairment (7). These findings are bolstered by a recent longitudinal analysis from the Salisbury Eye Evaluation study, which indicates that impaired visual acuity is associated with declining cognitive function both cross-sectionally and longitudinally with worsening vision having a stronger association with declining cognition than the reverse (38). These results support the hypothesis that visual impairment is a risk factor for cognitive decline in older adults, supporting the downstream consequence hypothesis.

Our study aimed to enhance our understanding of the vision–cognition relationship by examining how objective measures of vision beyond visual acuity are associated with cognitive function in late life. Recent analysis of data from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures found that participants in the lowest quartile of contrast sensitivity function have more than twice the risk of incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia than those in the highest quartile (9). In addition, data from the Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study indicate that older adults with contrast sensitivity impairment are at increased risk of cognitive impairment over 10 years of follow-up (8). These results mirror our findings, which indicate that contrast sensitivity may be an important predictor of cognitive decline, suggesting that studies may need to assess more than visual acuity to fully characterize the relationship between visual impairment and cognitive outcomes. This study is among the first to explore the relationship between stereo acuity and cognitive outcomes, and our results suggest that older adults with stereo acuity impairment have greater cognitive decline and increased risk of cognitive impairment.

This study has limitations that must be considered when interpreting our results. First, visual impairment is clinically defined as best-corrected distance visual acuity in the better-seeing eye (19); however, the Health ABC Study only collected presenting visual acuity. Although presenting visual acuity indicates functional acuity, the visual acuity that an individual is likely utilizing for daily activities, best-corrected visual acuity provides information on the acuity that an individual would have with the appropriate spectacle correction. Therefore, we are unable determine if presenting visual acuity impairment is due to refractive error or eye disease that cannot be corrected with glasses or contacts within this population. Second, vision measures were only assessed at one time point, and we could not explore how changes in vision affect cognitive decline. Third, participants who were lost to follow-up were older, more likely to smoke and have diabetes, had worse 3MS and digit symbol scores, and had worse vision at baseline. Therefore, we can assume that this attrition most likely attenuated our results due to this survivor bias. Subsequent studies should work to address these limitations by including rigorous vision measures assessed at multiple time points, allowing more flexible modeling of the longitudinal relationship between vision and cognitive outcomes.

Our results indicate that among a population of high-physically functioning and non-demented older adults, visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and stereo acuity are risk factors for cognitive decline. These findings suggest that vision and eye health are important factors for healthy brain aging and support the need for research evaluating the effect of vision and eye health interventions on cognitive outcomes.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Intramural Research Program of the NIA, and NIA K01AG052640); Dr. Jane Kroger fund; and Wilmer Biostatistics Center Grant (NEI EY01765).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:614–618. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Varma R, Vajaranant TS, Burkemper B, et al. Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the united states: demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:802–809. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ong S-Y, Ikram MK, Haaland BA et al. Myopia and cognitive dysfunction: the Singapore Malay eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:799–803. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reyes-Ortiz CA, Kuo YF, DiNuzzo AR, Ray LA, Raji MA, Markides KS. Near vision impairment predicts cognitive decline: data from the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53219.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA, Sanchez L. Two-year decline in vision but not hearing is associated with memory decline in very old adults in a population-based sample. Gerontology 2001;47:289–293. doi: 10.1159/000052814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elyashiv SM, Shabtai EL, Belkin M. Correlation between visual acuity and cognitive functions. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:129–132. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lin MY, Gutierrez PR, Stone KL, et al. ; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group Vision impairment and combined vision and hearing impairment predict cognitive and functional decline in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1996–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52554.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fischer ME, Cruickshanks KJ, Schubert CR, et al. Age-related sensory impairments and risk of cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:1981–1987. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ward ME, Gelfand JM, Lui LY, et al. Reduced contrast sensitivity among older women is associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2018;83:730–738. doi: 10.1002/ana.25196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Health ABC Website. Introducing the Health ABC Study: the dynamics of health, aging, and body composition https://healthabc.nia.nih.gov. Accessed December 6, 2018.

- 11. Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Nevitt MC, et al. Measuring higher level physical function in well-functioning older adults: expanding familiar approaches in the Health ABC study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M644–M649. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.M644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swenor BK, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. Visual impairment and incident mobility limitations: the health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:46–54. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bailey IL, Lovie JE. New design principles for visual acuity letter charts*. Optom Vis Sci. 1976;53:740–745. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197611000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lovie-Kitchin JE. Validity and reliability of visual acuity measurements. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1988;8:363–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1988.tb01170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pelli D, Robson J. The design of a new letter chart for measuring contrast sensitivity. In: Clinical Vision Sciences: 1988. Citeseer; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Elliott DB, Sanderson K, Conkey A. The reliability of the Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity chart. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1990;10:21–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-1313.1990.tb01100.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sasieni L. The Frisby stereotest. Optician 1978;176:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chou C-F, Cotch MF, Vitale S, et al. Age-related eye diseases and visual impairment among US adults. Am J Prev Med 2013;45:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Eye Institute (NEI). Definitions https://nei.nih.gov/eyedata/defined Accessed March 20, 2018.

- 20. Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver C, et al. ; Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mäntyjärvi M, Laitinen T. Normal values for the Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity test. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:261–266. doi: 10.1016/S0886-3350(00)00562-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scale WD. Wechsler Adult Intelligence, Administration and Scoring Manual. 3rd ed San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Teng EL, Chui HC. The modified mini-mental state (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kurella M, Chertow GM, Fried LF, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment in the elderly: the health, aging, and body composition study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2127–2133. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Penninx B, et al. Inflammatory markers and cognition in well-functioning African-American and white elders. Neurology 2003;61:76–80. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000073620.42047.D7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuller LH, Lopez OL, Newman A, et al. Risk factors for dementia in the cardiovascular health cognition study. Neuroepidemiology 2003;22:13–22. doi: 10.1159/000067109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173:293–299. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mine M, Miyata K, Morikawa M, et al. Association of visual acuity and cognitive impairment in older individuals: Fujiwara-kyo Eye study. Biores Open Access. 2016;5:228–234. doi: 10.1089/biores.2016.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spierer O, Fischer N, Barak A, Belkin M. Correlation between vision and cognitive function in the elderly: a cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2016;95:e2423. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bruhn P, Dammeyer J. Assessment of dementia in individuals with dual sensory loss: application of a tactile test battery. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2018;8:12–22. doi: 10.1159/000486092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Busse A, Sonntag A, Bischkopf J, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Adaptation of dementia screening for vision-impaired older persons: administration of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:909–915. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wittich W, Phillips N, Nasreddine ZS, Chertkow H. Sensitivity and specificity of the Montreal cognitive assessment modified for individuals who are visually impaired. J Vis Impair Blind. 2010;104:360–368. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen SP, Bhattacharya J, Pershing S. Association of vision loss with cognition in older adults. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:963–970. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salthouse TA, Hancock HE, Meinz EJ, Hambrick DZ. Interrelations of age, visual acuity, and cognitive functioning. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1996;51:P317–P330. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51B.6.P317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wayne RV, Johnsrude IS. A review of causal mechanisms underlying the link between age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;23(Pt B):154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wahl H-W, Heyl V. Connections between vision, hearing, and cognitive function in old age. Generations 2003;27:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zheng DD, Swenor BK, Christ SL, West SK, Lam BL, Lee DJ. Longitudinal associations between visual impairment and cognitive functioning: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:989–995. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.2493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.