Abstract

Background: The diagnosis of solitary cutaneous mastocytoma is mainly clinical, based on lesion morphology, the presence of a positive Darier sign, and the absence of systemic involve-ment. Knowledge of this condition is important so that an accurate diagnosis can be made.

Objective: To familiarize physicians with the clinical manifestations, diagnosis, evaluation, and man-agement of a solitary cutaneous mastocytoma.

Methods: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term “solitary cutane-ous mastocytoma”. The search strategy included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, observational studies, and reviews. Only papers published in English language were included. The information retrieved from the above search was used in the compilation of the present article.

Results: Typically, a solitary cutaneous mastocytoma presents as an indurated, erythematous, yellow-brown or reddish-brown macule, papule, plaque or nodule, usually measuring up to 5 cm in diameter. The lesion often has a peau d'orange appearance and a leathery or rubbery consistency. A solitary cu-taneous mastocytoma may urticate spontaneously or when stroked or rubbed (Darier sign). Organo-megaly and lymphadenopathy are characteristically absent. The majority of patients with skin lesions that erupt within the first two years of life have spontaneous resolution of the lesions before puberty. Treatment is mainly symptomatic. Reassurance and avoidance of triggering factors suffice in most cases.

Conclusion: The diagnosis is mainly clinical, based on the morphology of the lesion, the presence of a positive Darier sign, and the absence of systemic involvement. A skin biopsy is usually not neces-sary unless the diagnosis is in doubt.

Keywords: Indurated, hyperpigmented, macule, papule, plaque, nodule, Darier sign

1. INTRODUCTION

A mastocytosis is a heterogeneous group of clonal hematopoietic disorders characterized by a pathologic accumulation of mast cells in tissue, such as the skin, bone marrow, liver, spleen, gastrointestinal tract, and lymph nodes [1]. Mast cell accumulation can be limited to the skin (cutaneous mastocytosis) or involve extracutaneous tissues, often in combination with skin involvement (systemic mastocytosis) [1]. Cutaneous mastocytosis can be subclassified into solitary cutaneous mastocytoma, maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (urticaria pigmentosa), and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis [1-3]. Solitary cutaneous mastocytoma was first described in 1889 by Nettleship [4].

A PubMed search was conducted in February 2018 using Clinical Queries with the key term “solitary cutaneous mastocytoma” using a broad scope for the categories of etiology, diagnosis, therapy, and prognosis. Meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, observational studies, and reviews were considered for inclusion. Only papers published in the English literature were included. Discussion is based on, but not limited to, the search results.

2. EPIDEMIOLOGY

It is estimated that mastocytosis has a prevalence rate of 9 cases per 100,000 persons in the USA [5, 6]. In the pediatric age group, more than 80% of these patients have cutaneous mastocytosis [6, 7]. Solitary cutaneous mastocytoma accounts for 10 to 15% of all pediatric cases of cutaneous mastocytosis [3, 8-11]. Congenital cases have been described in approximately 60% of patients [12]. Typically, the age of onset is in infancy, especially in the first 3 months of life [8, 9, 11, 13, 14]. Cases with onset in adulthood have, very rarely, been reported [3, 4, 15]. The sex ratio is approximately equal [16]. The condition is more commonly reported in Caucasian patients [1]. The majority of cases are sporadic. Familial cases have also been reported [5].

3. ETIOPATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The c-KIT proto-oncogene, located on chromosome 4q12, encodes KIT (the receptor for stem cell factor, also called CD117), a transmembrane protein that binds to stem cell factor and promotes cell division [1]. Activating (gain-of-function) and, less commonly, non-activating mutations in the c-KIT proto-oncogene have been shown to result in an abnormal proliferation of mast cells and melanocytes.17 Approximately 40% of children with cutaneous mastocytosis have exon 17 KIT mutations, another 40% have KIT mutations outside exon 17 (e.g., exon 8, 9, 10, 11), and the remaining have no detectable KIT mutations [2, 16, 17]. Stem cell factor plays an important role in mast cell development and increased expression of stem cell factor has been found in some children with cutaneous mastocytosis [17]. Solitary cutaneous mastocytoma has been reported to develop at sites of trauma, such as a vaccination site [18, 19]. It is postulated that stem cell factor, nerve growth factor, and interleukin-5 are released as a result of trauma and may stimulate the proliferation of mast cells and formation of solitary cutaneous mastocytoma [18, 19].

It has been shown that local concentrations of soluble mast cell growth factors are increased in solitary cutaneous mastocytoma, with induction of melanocytes [15, 20]. Proliferation of melanocytes leads to local production of melanin pigment. This accounts for the hyperpigmented appearance of the lesion seen in solitary cutaneous mastocytoma [21].

Symptoms and signs such as pruritus, flushing, and wheals with stroking, rubbing or scratching are caused by spontaneous or induced activation of mast cells with resulting release of vasoactive mediators [21]. These mast cell mediators include histamine, heparin, proteases (tryptase, chymase), cysteinyl leukotrienes, prostaglandins, platelet-activating factor, growth factors (interleukin-3, interleukin-5, interleukin-6), and cytokines (nerve growth factor, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, transforming growth factor-beta) [17].

Common triggers include mechanical irritation (e.g., local friction, rubbing, massage, stroking), surgical trauma (e.g., vaccinations, tooth extraction, surgery), physical exertion, emotional stress, extremes of temperature (e.g., very cold or hot baths), alcohol ingestion, hot beverages, spicy foods, cheese, drugs (dextromethorphan, aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anticholinergic medications, thiamine, procaine, antibiotics [e.g., penicillins, vancomycin, polymyxin B sulphate], opiates [e.g., codeine, morphine], muscle relaxants [e.g., succinylcholine, rocuronium, atracurium]), iodinated radiocontrast agents, venomous snake bites, jellyfish stings, and hymenoptera stings [8, 13, 17, 21, 22].

4. HISTOPATHOLOGY

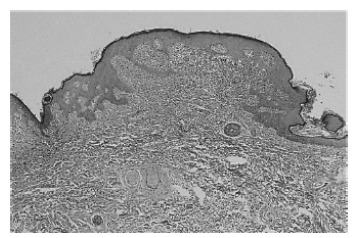

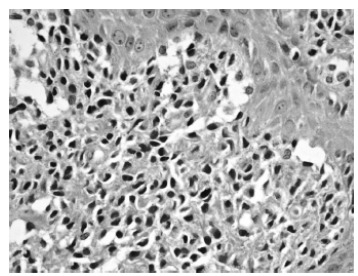

Histological findings include increased melanization of the basal layer with dense aggregates of mast cells infiltrating the upper and mid dermis (Figs. 1 and 2). Mast cells are best observed using special stains such as Giemsa, toluidine blue, Astra blue, and Leder (chloroacetate esterase). The round mast cell nucleus with surrounding cytoplasm gives rise to a “fried egg” appearance. Metachromatic intracytoplasmic granules can be easily recognized with the aforementioned stains [21, 23]. Immunohistochemistry requires 15 or more mast cells in aggregates or greater than 20 mast cells per high field for the diagnosis to be confirmed [14].

Fig. (1).

Increased melanization of the basal layer with dense aggregates of mast cells infiltrating the upper and mid dermis (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification x 40).

Fig. (2).

Mast cells are round or spindled-shaped with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei. The cytoplasm contains basophilic granules (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification x 400).

5. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The most common presentation is an indurated, erythematous, yellow-brown or reddish-brown, round or oval macule, papule, plaque or nodule, usually 1 to 5 cm in diameter (Fig. 3) [8, 9, 13, 24-26]. The lesion often has a peau d'orange (pebbly, orange peel-like) appearance and a leathery or rubbery consistency [9, 12, 21, 26, 27]. The lesional margins can be indistinct or sharp [2]. Pruritus is variable; the lesion can be asymptomatic or moderately pruritic [9, 13, 17]. It usually increases in size for several months and then grows in proportional to the size of the child for a variable period of time before regressing over time [26]. Sites of predilection include the trunk, extremities, and flexural areas, followed by the head and neck [8, 13, 26]. The palms and soles are usually spared [12, 21, 28]. The lesion may spontaneously urticate and/or, more commonly, urticate when stroked or rubbed [21, 26]. Upon stroking or rubbing, the lesion becomes pruritic, erythematous, or edematous; this reaction is referred to as the Darier sign (Fig. 4) [13, 21, 26]. This sign, caused by the release of mast cell mediators induced by physical stimulation, is considered pathognomonic [13]. As a positive Darier sign can only be elicited in approximately 50% and 90% of patients with solitary mastocytoma and other types of cutaneous mastocytosis, respectively, the absence of a Darier sign does not exclude the diagnosis of mastocytosis [10, 22]. Some of the lesions may blister with irritation [2, 4, 8, 21]. Although systemic symptoms such as flushing, dyspnea, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and headache are much more commonly seen in patients with systemic mastocytosis, they can also occur in patients with solitary cutaneous mastocytosis [21, 25]. As such, the lesion of solitary cutaneous mastocytoma should not be vigorously rubbed and the Darier sign should not be elicited in case of a large mastocytoma as such maneuver can precipitate severe symptoms [6, 17]. Organomegaly and lymphadenopathy are characteristically absent [6].

Fig. (3).

A solitary cutaneous mastocytoma presenting as a reddish brown plaque on the left posterior thigh of a 4-month-old infant. The lesion had a cobblestone, “peau d’orange” surface.

Fig. (4).

With rubbing, the plaque became urticarial with a surrounding flare of erythema (Darier sign).

6. LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS

Baseline laboratory investigations may include complete blood cell count, liver function tests (including serum alanine transaminase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and bilirubin), and serum tryptase level [25]. The aforementioned tests are usually normal in patients with solitary cutaneous mastocytoma [2, 6]. An elevated serum tryptase level and systemic symptoms/signs, however, may result after mechanical irritation of a solitary cutaneous mastocytoma [29]. Therefore, mechanical irritation such as stroking of a solitary cutaneous mastocytoma should be avoided prior to bloodletting. These blood tests should be repeated on a yearly basis [30]. An unprovoked elevated serum tryptase level (>20 ng/ml) is suspicious and may suggest systemic mastocytosis, especially if the complete blood count and liver function tests are abnormal and/or if splenomegaly/heptatomegaly/ lymphadenopathy are present [30].

7. SKIN BIOPSY

A skin biopsy is usually not necessary unless the diagnosis is in doubt. If a skin biopsy is performed, the specimen should be sent for histopathological examination and, if necessary, for analysis of KIT mutations [30]. Premedication with an oral corticosteroid and antihistamines (H1 and H2) may be considered to minimize the adverse effects of mast cell mediators released during the biopsy [30].

8. DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is mainly clinical, based on the morphology of the lesion, the presence of a positive Darier sign, and absence of systemic involvement [5]. Dermoscopy typically shows a light-brown blot and a pigment network that corresponds to the accumulation of melanin in basal keratinocytes. The diagnosis can be confirmed, if necessary, by a skin biopsy that confirms infiltrate of mast cells in the dermis and demonstration of KIT mutation in lesional skin.

9. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Solitary cutaneous mastocytoma should be differentiated from maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (urticaria pigmentosa) and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis. Typically, maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis presents with pruritic, yellow-tan to reddish-brown macules/papules on the trunk and proximal extremities. The lesions are polymorphic and are larger than those seen in adult-onset ones. The margins can be indistinct or sharp. Nodules and plaques may also occur and these lesions usually flatten with time. In contrast to solitary cutaneous mastocytoma where the Darier sign is positive in 50% of cases, in maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, the Darier sign is positive in 90% of cases [10, 22]. Whereas in solitary cutaneous mastocytoma, pruritus is variable; in maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis, pruritus is the most common symptom. Dermographism is often present. Flares and flushing are more commonly seen in patients with urticaria pigmentosa than in patients with solitary cutaneous mastocytoma. Organomegaly and lymphadenopathy are characteristically absent in both conditions.

Characteristically, patients with diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis present with flushing, pruritus, widespread urticaria evolving into blisters/bullae, erosions, and crusts. The involvement is extensive; it is not uncommon for the entire skin to be affected. The blisters/bullae may become hemorrhagic with time. Positive Darier sign and strong dermographism are hallmarks of diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis. Other characteristic findings include generalized thickening of the skin (pachyderma) with a leathery or peau d’orange appearance, erythroderma, and increased folding in the skin creases. Superimposed nodules and plaques at sites of dense mast cell infiltrates are common.

Other differential diagnoses include juvenile xanthogranuloma, xanthoma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, epidermolysis bullosa simplex, allergic contact dermatitis, café-au-lait macule, bruise, melanocytic nevus, Spitz nevus, amelanotic melanoma, neurofibroma, granuloma annulare, granuloma faciale, hemangioma, nodular scabies, arthropod bite, drug-related eruption, histiocytosis, leukemia cutis, chronic urticaria, herpes simplex, bullous impetigo, hidrocystoma, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis [15, 21, 24-27].

10. COMPLICATIONS

Anaphylaxis, though uncommon, may occur, especially in those with blistering skin disease [11]. Rarely, progression of solitary cutaneous mastocytoma to systemic mastocytosis, mast cell leukemia, and cutaneous mast cell sarcoma has been reported [7, 31, 32].

11. PROGNOSIS

In general, the prognosis is excellent. The majority of patients with solitary cutaneous mastocytomas whose onset of skin lesions are within the first two years of life have spontaneous resolution of the lesions without scarring before puberty, with significant improvement in the remaining patients [12, 13, 21, 28]. In some patients who have onset of the disease after the age of two years, the disease may persist into adulthood [32].

12. MANAGEMENT

Treatment is mainly symptomatic. Reassurance and avoidance of triggering factors suffice in most cases [6, 27]. Oral H1 antihistamines (e.g., hydroxyzine, loratadine, desloratadine, cetirizine, levocetirizine, fexofenadine) are the cornerstone of treatment for pruritus and flushing [1, 32]. In severe cases, oral H2 antihistamines (e.g., ranitidine, cimetidine, famotidine) can be added for additional benefit [1, 6, 32]. Oral H2 antihistamines with or without oral cromoglycate (cromolyn sodium) should be considered for those with gastrointestinal symptoms attributable to solitary cutaneous mastocytoma such as heartburn, abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea [6, 32]. Preventative measures include the use of lukewarm water for bathing, air conditioning when the weather is hot, and elimination/avoidance of triggering factors [32].

Patients with solitary cutaneous mastocytomas are at risk for anaphylaxis, though the risk is much lower than the other types of mastocytosis. Caregivers as well as affected patients over the age of seven years should be taught how to self-administer epinephrine and should have an epinephrine auto-injector such as Anapen/Anapen Jr, EpiPen/EpiPen Jr, or Twinjet/Twinjet Jr and antihistamine available at all times in case of acute event leading to extensive mast cell degranulation [23]. For the treatment of anaphylaxis, the recommended dose of epinephrine 1:1000 (1 mg/ml) is 0.01 mg/kg intramuscularly, up to a maximum of 0.3 mg (0.3 ml) in children and 0.5 mg (0.5 ml) in adults [33]. Wearing an identification necklace or bracelet such as MedicAlert or Medi-Tag stating the patient’s medical condition should be considered.

Parents should be reassured the excellent prognosis of this condition and that the lesion would likely resolve spontaneously with time, especially if the onset of the lesion is within the first two years of life. Surgical resection of a solitary cutaneous mastocytoma is usually not necessary unless symptoms are severe [31]. Should surgical procedures such as biopsy or surgical removal of the tumor be necessary, premedication with an oral corticosteroid and antihistamines (H1 and H2) may be considered.

CONCLUSION

Solitary cutaneous mastocytomas are most commonly seen in infancy. The majority of these lesions improve spontaneously over several years duration and resolve before puberty. Treatment is mainly symptomatic. Reassurance and avoidance of triggering factors suffice in most cases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Professor Alexander K.C. Leung is the principal author. Dr. Joseph M. Lam and Dr. Kin Fon Leong are coauthors. All the authors contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Professor Alexander K. C. Leung, Dr. Joseph M. Lam, and Dr. Kin Fon Leong confirm that this article has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leung A.K., Barankin B. Urticaria pigmentosa. Consult Pediatr. 2016;15:311–313. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartmann K., Escribano L., Grattan C., et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: Consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;137(1):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma S.P., Hardy T.G. Solitary Mastocytoma of the eyelid in an adult patient with prolidase deficiency. Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2017;33(1):e10–e13. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandhi D., Singal A., Aggarwal S. Adult onset, hypopigmented solitary mastocytoma: Report of two cases. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2008;74(1):41–43. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.38407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azaña J.M., Torrelo A., Matito A. Update on mastocytosis (Part 1): pathophysiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaiber N., Kumar S., Irani A.M. Mastocytosis in Children. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17(11):80. doi: 10.1007/s11882-017-0748-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auquit-Auckbur I., Lazar C., Deneuve S., et al. Malignant transformation of mastocytoma developed on skin mastocytosis into cutaneous mast cell sarcoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012;36(5):779–782. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31824c0d92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briley L.D., Phillips C.M. Cutaneous mastocytosis: A review focusing on the pediatric population. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 2008;47(8):757–761. doi: 10.1177/0009922808318344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopal D., Puri P., Singh A., Ramesh V. Asymptomatic solitary cutaneous mastocytoma: A rare presentation. Indian J. Dermatol. 2014;59(6):634. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.143588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan K.R., Ownby D.R. A solitary mastocytoma presenting with urticaria and angioedema in a 14-year-old boy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(6):520–523. doi: 10.2500/aap.2010.31.3368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tüysüz G., Özdemir N., Apak H., Kutlubay Z., Demirkesen C., Celkan T. Childhood mastocytosis: Results of a single center. Turk. Pediatri Ars. 2015;50(2):108–113. doi: 10.5152/tpa.2015.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azaña J.M., Torrelo A., Matito A. Update on mastocytosis (Part 2): Categories, prognosis, and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Giorgi V., Fabroni C., Alfaioli B., et al. Solitary mastocytoma: Tooth eruption as triggering factor. Int. J. Dermatol. 2008;47(12):1274–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKinnon E.L., Rand A.J., Proia A.D. Solitary mastocytoma in the eyelid of an adult. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2018;9:103–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen P.R. Solitary mastocytoma presenting in an adult: Report and literature review of adult-onset solitary cutaneous mastocytoma with recommendations for evaluation and treatment. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2016;6(3):31–38. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0603a07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiechers T., Rabenhorst A., Schick T., Preussner L.M., Förster A., Valent P., et al. Large maculopapular cutaneous lesions are associated with favorable outcome in childhood-onset mastocytosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136(6):1581–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castells M.C., Akin C. Mastocytosis (cutaneous and systemic): Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestations. In: Post T.W., editor. Up To Date. Waltham, MA: (Accessed on March 30, 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh M.J., Chong W.S. Red plaque after hepatitis B vaccination. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2008;25(3):381–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuxen A.J., Orchard D. Solitary mastocytoma occurring at a site of trauma. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2009;50(2):133–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2009.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okun M.R. Mast cells, melanocytes, balloon cells. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 1982;4(5):478–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bulat V., Mihić L.L., Situm M., Buljan M., Blajić I., Pusić J. Most common clinical presentations of cutaneous mastocytosis. Acta Clin. Croat. 2009;48(1):59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conrad H., Gausche-Hill M., Burbulys D. A 6-month old with total body flushing and a macular-papular lesion. Pediatr. Emerg. Care. 2007;23(5):321–323. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000270165.85862.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horny H.P., Sotlar K., Valent P. Mastocytosis: State of the art. Pathobiology. 2007;74(2):121–132. doi: 10.1159/000101711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourji L., Kurban M., Abbas O. Solitary mastocytoma mimicking granuloma faciale. Int. J. Dermatol. 2014;53(12):e587–e588. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Exposito-Serrano V., Agut-Busquet E., Leal Canosa L., Herrerías Moreno J., Saez A., Luelmo J. Pleomorphic mastocytoma in an adult. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2018;45(2):176–179. doi: 10.1111/cup.13080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gori A., Torneria C., Kelly V.M., Zlotoff B.J., Contreras M.E. Visual diagnosis: Two infants who have skin lesions that react to minor trauma. Pediatr. Rev. 2009;30(7):280–283. doi: 10.1542/pir.30-7-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nair B., Sonthalia S., Aggarwal I. Solitary mastocytoma with positive Darier’s sign. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2016;7(2):141–142. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.178091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janakiramanan N., Chambers D., Dowling G.J. A rare presentation of solitary mastocytoma in the palm of an infant. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2010;63(2):e197–e198. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bussmann C., Hagemann T., Hanfland J., Haidl G., Bieber T., Novak N. Flushing and increase of serum tryptase after mechanical irritation of a solitary mastocytoma. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2007;17(4):332–334. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castells M.C., Akin C. Mastocytosis (cutaneous and systemic): evaluation and diagnosis in children. In: Post T.W., editor. Up To Date. Waltham, MA: (Accessed on March 30, 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castells M.C., Akin C. Treatment and prognosis of cutaneous mastocytosis. In: Post T.W., editor. Up To Date. Waltham, MA: (Accessed on March 30, 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chantorn R., Shwayder T. Death from mast cell leukemia: A young patient with longstanding cutaneous mastocytosis evolving into fatal mast cell leukemia. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2012;29(5):605–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muraro A., Roberts G., Clark A., et al. The management of anaphylaxis in childhood: Position paper of the European academy of allergology and clinical immunology. Allergy. 2007;62(8):857–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]