Abstract

Children with cerebral palsy (CP) require ongoing rehabilitation services to address complex health care needs. Attendance at appointments ensures continuity of care and improves health and well-being. The study’s aim was to gain insight into mothers’ perspectives of the factors associated with nonattendance. A qualitative descriptive design was conducted to identify barriers and recommendations for appointment keeping. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 mothers of children with CP. Data underwent inductive qualitative analysis. Mothers provided rich context regarding barriers confronted for appointment keeping—transportation and travel, competing priorities for the child and family, and health services. Mothers’ recommendations for improving the experience of attending appointments included virtual care services, transportation support, multimethod scheduling and appointment reminders, extended service hours, and increased awareness among staff of family barriers to attendance. The results inform services/policy strategies to facilitate appointment keeping, thereby promoting access to ongoing rehabilitation services for children with CP.

Keywords: cerebral palsy, children, disability, health and well-being, health care, access to, lived experience, mothers, mothering, qualitative research, rehabilitation

Introduction

Children who have cerebral palsy (CP) require more health care services than their nondisabled peers (Young et al., 2007) and are at greater risk of having unmet health care needs and comorbidities (Blackman & Conaway, 2014; Jackson, Krishnaswami, & McPheeters, 2011). CP, the most common pediatric neuromotor condition (Chamberlain & Kent, 2005), is a group of disorders characterized by impaired movement and muscle tone that is often accompanied by involvement in other areas such as cognition, communication, and behavior (Blackman & Conaway, 2014; Rosenbaum et al., 2007) and may involve comorbid conditions such as autism (Blackman & Conaway, 2014). As a result, children who have CP require a plethora of regular and ongoing rehabilitation services such as occupational, physical, and speech language therapy as well as physician, psychology, and nursing services. Moreover, because frequent and timely therapy is necessitated (Markowitz, Volkening, & Laffel, 2014), children who have CP also require services that are well-coordinated and easily accessible (Majnemer et al., 2014).

Caring for a child with CP who has complex health care needs is physically and psychologically demanding for parents (Raina et al., 2005). Within this arduous caregiving context, parents are also responsible for ensuring that their children attend rehabilitation appointments on an ongoing basis. Consequently, preparing for, traveling to, and attending appointments may be quite challenging for parents. Nonattendance at appointments can be greater for children with developmental disabilities who require multiple services (Kalb et al., 2012). This potential for interruptions in the timely receipt of rehabilitation services has important medical, social, and emotional consequences, as the continuity of care may be compromised (Arai, Stapley, & Roberts, 2014; Pesata, Pallija, & Webb, 1999). In addition, nonattendance at appointments is inefficient, costly, and a waste of health care services due to unused clinician time and valuable resources (Ballantyne & Rosenbaum, 2017; Dantas, Fleck, Oliveira, & Hamacher, 2018).

Despite the need for frequent and consistent care within a demanding care context, there is a paucity of research exploring the experience of appointment keeping for children who have complex developmental disabilities. Ensuring that parents of children with disabilities are supported in the rehabilitation care environment is medically and socially responsible. Acquiring an understanding of the barriers that impede as well as the pertinent facilitators that support appointment keeping for families is critical. This information will be relevant to policy makers to reconfigure the health system to better address the needs of children with CP as well as their families. Gaining a better appreciation of the family caregiving experience is needed to assist not only families who may require support but also for health care providers to better prepare and learn how to assist.

The use of theory among these studies is also a limitation of this body of literature with little to no theoretical guidance cited in the research. The majority of previous pediatric research has focused on identifying predictors of nonattendance within specialty and primary care settings. Several studies have identified variables that predict nonattendance using administrative data. Some of these studies focus on family-level variables, such as age, gender, distance traveled, and diagnoses (Ballantyne, Stevens, Guttmann, Willan, & Rosenbaum, 2014; Chariatte, Berchtold, Akré, Michaud, & Suris, 2008; Gordon, Antshel, Lewandowski, & Seiger, 2010; Mallow, Theeke, Barnes, Whetsel, & Mallow, 2014), whereas others measure both family- and system-level factors such as scheduling time and type of care provider (Anwar, Cooper, Gerard, & Storm, 2017; Chariatte, Michaud, Berchtold, Akré, & Suris, 2007; Cohen, Goldbart, Levi, Shapiro, & Vardy, 2007; Cordiner, Logie, & Becher, 2010; Dantas et al., 2018; Drieher, Goldbart, Hershkovich, Vardy, & Cohen, 2008; Goldbart, Dreiher, Vardy, Alkrinawi, & Cohen, 2009; Guzek, Fadel, & Golomb, 2015; Hon, Leung, Wong, Ma, & Fok, 2005; Huang & Hanauer, 2014; Humphreys et al., 2000; Kalb et al., 2012; Lamberth et al., 2002; Markowitz et al., 2014; McLeod, Heath, Cameron, Debelle, & Cummins, 2015; Samuels et al., 2015; Sherman, Barnum, Buhman-Wiggs, & Nyberg, 2009; Yoon, Davis, Cleave, Maheshwari, & Cabana, 2005). These studies were conducted with the primary goal of improving attendance rates to decrease system inefficiency and reduce costs. With the exception of four studies (Guzek et al., 2015; Hon et al., 2005; Humphreys et al., 2000; Samuels et al., 2015), reasons for nonattendance were not addressed. Although identifying predictors may be useful for characterizing particular families who are at risk of nonattendance, the exploration of modifiable barriers and the development of potential facilitators are absent.

The small number of studies that have explored the reasons for nonattendance did so by presenting frequency counts of parents’ reported explanations (Guzek et al., 2015; Hon et al., 2005; Humphreys et al., 2000; Samuels et al., 2015). These studies were conducted in specialty or primary care settings and in one study; almost half of the participants were involved in well-care appointments (Samuels et al., 2015). Only one study included returning families (Guzek et al., 2015) and two were limited to attendance of referral appointments (Hon et al., 2005; Humphreys et al., 2000). In addition, one provided data for both pediatric and adult patients together (Humphreys et al., 2000). Although these studies begin to identify reasons for appointment nonattendance such as parent forgetting (Guzek et al., 2015; Hon et al., 2005; Samuels et al., 2015) and scheduling conflicts (Guzek et al., 2015; Humphreys et al., 2000; Samuels et al., 2015), context specific information is limited, and no data were collected about facilitators or recommendations for appointment keeping.

Four qualitative studies have been conducted to explore appointment keeping in pediatric settings (Ballantyne, Benzies, Rosenbaum, & Lodha, 2015; Cameron et al., 2014; Schneiderman, Kennedy, & Sayegh, 2017; Touch & Berg, 2016). Three of these studies examined barriers and facilitators, however, with less attention to facilitators (Ballantyne et al., 2015; Cameron et al., 2014; Touch & Berg, 2016). Although one study was devoted exclusively to facilitators of attendance (Schneiderman et al., 2017), it was not conducted with children who had disabilities. These four qualitative studies were conducted in primary and specialty pediatric. As a result, these studies elicited perceptions of children with more acute care needs and with a relatively short-term and/or limited experience in the health care system.

Only two studies have specifically addressed appointment keeping for children who have disabilities (Guzek et al., 2015; Kalb et al., 2012). One utilized medical chart data to determine child, family, and clinic predictors for nonattendance within an outpatient Autism Spectrum Disorder clinic including African American child race, family social assistance, provider type, and time of the appointment (Kalb et al., 2012). In the other, family- and provider/system-level predictors of nonattendance were measured in a pediatric neurology clinic, and reasons for nonattendance were presented as frequency counts (Guzek et al., 2015). This pilot study reported medical social assistance, distance from clinic, and time since last appointment as key predictors, and scheduling conflicts, forgetting the appointment, and travel distance as reasons for nonattendance (Guzek et al., 2015). Although these studies provide some insight, a deeper understanding of the context that surrounds the challenges and facilitators for parents was not obtained.

To date, no research has focused on parents’ perspectives of the challenges of appointment keeping in a context that is fraught with intense caregiving and frequent appointment demands. Exploring the barriers and reasons for nonattendance in this population will highlight areas for improving access to care and potentially improve long-term outcomes. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to gain insight into the perspectives of mothers of children with developmental disabilities and the factors associated with nonattendance. Our objective was to identify (a) the barriers that may result in these children being unable to attend their health care appointments and (b) recommendations that can promote appointment keeping as well as improve the experience for children and their families from mothers’ perspectives.

Method

A qualitative descriptive design as described by Sandelowski (2000) was used to explore and present mothers’ experiences with their children’s health care appointments. As the experience of appointments is influenced by mothers’ relationships with their children as well as interactions with the broader health care system, qualitative descriptive methods were selected as a means of gaining insight into mothers’ perspectives, using their own words. A qualitative methodological approach permits a comprehensive understanding of a health care phenomenon (Sandelowski, 2000) and is thus appropriate for this study because of the human experience and complex care environment. The naturalistic approach as used by Sandelowski (2000) implies a commitment to studying experiences as close to what it would be in its natural state and by using their own words.

Sampling and Setting

Purposeful criterion sampling strategies were used to recruit mothers of children with CP who had long-term experience with caregiving and attending multiple health care appointments (Patton, 1990). Eligibility criteria included mothers who (a) were a primary caregiver of a child with CP between the ages of 1 and 18 years, (b) had not attended two or more scheduled appointments with their child at the study site within the prior 12 to 24 months, and (c) could read and speak English. The criteria of two or more nonattended appointments would allow the mothers to have experiences to reflect on and is a quantity that is consistent with previous research (Tin, Fritz, Wariyar, & Hey, 1998). Mothers whose children were in the first year of service at the study site were excluded because many children attend only one appointment in the first year. Mothers were selected as the focus of this study because mothers are primarily available and usually attend appointments with their children.

The data collection site is the largest pediatric rehabilitation hospital located in the most population dense, urbanized center in Canada. This hospital has been operating for almost 70 years and is reflective of current practices and service delivery of rehabilitation care in Canada. It is an academic teaching hospital that provides multidisciplinary rehabilitation services for 7,400 children with disabilities, including 55,000 outpatient visits, per year. CP is one of the top three diagnoses among the hospital clients. The hospital outpatient services for children with CP (e.g., neuromotor clinics) serve families located in this urban city. Participants were recruited from the neuromotor clinics.

Procedures

Ethics approval was obtained by the Holland Bloorview Research Ethics Board (#15-588). Participants were recruited from November 2015 to August 2016 through a study flyer and verbal invitation extended by a staff member who was not involved in the study. Following informed consent, one individual interview was conducted with each participant. The lengths of the interview varied for each participant and were up to 30 minutes in duration.

A research assistant and the primary author, who have experience in family interviewing, used a semi-structured interview guide (see Table 1). Questions were adapted and developed by the research team based on their previous work (Ballantyne et al., 2015; Ballantyne & Rosenbaum, 2017). All interviews were conducted by telephone for ease of participation for mothers. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and verified for accuracy, confidentiality, and anonymity. At the end of each interview, participants completed a demographic questionnaire. The interviewer recorded observations in field notes. Participants were given a Can $25.00 gift voucher at the completion of their interview.

Table 1.

Semi-Structured Interview Guide.

| Focus | Questions |

|---|---|

| Experiences | Think about a time when you could not attend an appointment at X (site name). Please share a story about your experience. What was the experience like for you and your child? |

| Barriers and reasons | Were there other times when you wanted to attend appointments but could not? What makes it difficult for you to attend appointments with your child? What barriers have you experienced that led to missing an appointment? What other reasons would you like to share? Think about any reasons that are about you, your child and family and/or how the clinic operates? |

| Recommendations | What would make it easier to attend appointments? Is there anything else you would like to share about your experiences that would help to improve services for you and your family? |

Data Analysis

Qualitative data analysis (Boyartzis, 1998) occurred during both the data collection and data analysis processes. Analysis followed the six phases of inductive analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (2006) and these phases were conducted by four members of the research team until data saturation was achieved. First, the data transcripts and field notes were independently read several times (Phase 1) and then initial codes were developed; codes identify a feature of the data that is related to the research question and is the most basic element of the data (Phase 2). As the analysis process proceeded, codes were sorted and grouped into potential categories (Phase 3). Categories were expanded or collapsed as needed to capture the conceptualization of barriers of nonattendance using the coded data. A categories map was developed and shared to ensure consistency across transcripts and between the four analyzers (Phase 4). Phase 5 was the formal definition and naming of categories and the final step. Phase 6 was to produce a report using examples of categories that address the research question. All analysis decisions were developed through team consensus and all discrepancies were discussed until consensus was achieved. Qualitative analysis was conducted manually and tracked systematically using color-coding for recurrent codes and categories indicating barriers and recommendations (study objectives) across each phase. Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability were addressed to ensure trustworthiness (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Credibility strategies include regular debriefing team meetings to discuss data collection and analysis processes, keeping an audit trail of decision making and evolving coding schemes and a diverse research team with varied field experience (i.e., nursing, social work, health services, operations; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Shenton, 2004). Transferability was addressed by purposeful criterion sampling, collecting demographic characteristics of participants, and comparing findings to existing literature. Dependability was addressed through investigator triangulation, prolonged engagement, and searching for rival explanations. Confirmability was addressed by using an audit trail, field notes, and investigators with diverse perspectives (Shenton, 2004).

Results

Seventeen mothers were asked to participate. Of these, 15 consented (88%). Two declined due to time constraints. Table 2 presents the study sample characteristics. The mothers who participated in this study were primarily of two-parent families (73%). Participants’ median age range was 30 to 39 years, median educational achievement was college-university graduate (46%), and the majority spoke English at home (80%). The median range of health care appointments for their child was two to three appointments per month with a range of one to more than 10 appointments per month.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics (N = 15).

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Family structure | |

| Two-parent family | 11 (73) |

| One-parent family | 4 (26) |

| Age range in years | |

| 20–29 | 5 (33) |

| 30–39 | 6 (40) |

| 40–49 | 3 (20) |

| 50–59 | 1 (7) |

| Highest education level | |

| Some high school | 2 (13) |

| High school graduate | 4 (26) |

| University/college graduate | 7 (46) |

| Graduate/professional training | 2 (13) |

| Current employment status | |

| Employed full-time | 6 (40) |

| Employed part-time | 5 (33) |

| At home full-time caregiver | 4 (26) |

| Primary language spoken in the home | |

| English | 12 (80) |

| Non-English | 3 (20) |

| Number of children | |

| One | 10 (67) |

| Two | 3 (20) |

| Three | 2 (13) |

| Travel mode | |

| Car | 11 (73) |

| Public transit | 2 (13) |

| Public wheelchair transit | 2 (13) |

| Travel time to hospital | |

| Less than 30 minutes | 3 (20) |

| 30 to 60 minutes | 8 (53) |

| 60 to 120 minutes | 4 (27) |

| Number of appointments/month | |

| 1 | 3 (20) |

| 2–5 | 6 (40) |

| 5–10 | 5 (33) |

| >10 | 1 (7) |

| Family annual income | |

| Less than $20,000 | 4 (26) |

| $20,000–$49,000 | 4 (26) |

| $50,000–$79,000 | 1 (7) |

| More than $80,000 | 5 (33) |

| Missing data | 1 (7) |

Mothers’ narratives provided context-rich data regarding the challenges that they confronted to attend appointments at the rehabilitation hospital for their children. Furthermore, mothers suggested several recommendations that they believed would assist families with appointment keeping and improve the rehabilitation care experience. Their accounts of their perceived barriers provided the precursor for and backdrop to their descriptions of recommended facilitators.

Perceived Barriers

The four primary categories representing mothers’ descriptions of barriers to appointment keeping are (a) transportation and travel, (b) competing priorities for the child, (c) competing priorities for the family, and (d) health care services. Figure 1 depicts each of the four primary categories and their inherent concepts. Below, direct quotations from participant mothers are provided to convey their perspectives and the meaning of each category.

Figure 1.

Mothers’ perceptions of barriers to attending appointments, by category.

Category 1: Transportation and travel

Mothers’ reports indicated that transportation barriers were often experienced when traveling to and from the rehabilitation hospital. They described an array of challenges that occurred during the planning phase as well as during the actual travel. Reported modes of transportation included personal car, publicly funded wheelchair accessible transit, and public transit. The most frequently reported one-way travel time was 30 to 60 minutes.

By personal car, mothers described challenges related to heavy traffic, driving in poor winter weather conditions, and high costs associated with gas and parking. For example, one mother described,

Traffic. Oh my goodness. On a good day we can get here [rehabilitation hospital] in 35 or 40 minutes. On a bad day, it can take an hour and a half. There was one day . . . I was driving . . . I had my child call his therapist on my cell pho ne because I can’t dial while I’m driving to say: “We’re stuck, we can’t make it. We’re just turning around and going home.” (Participant 3)

For those who traveled to appointments using publicly funded wheelchair accessible transit, challenges related to scheduling, access, and time were reported. One quotation illustrates the mother’s frustration in trying to schedule a ride and manage wait times:

When you do call they’ll say: “Oh no ma’am, we don’t see the thing available,” and I’ll say, “But I have to go to my appointment,” but they’ll say: “there’s nothing that we can do because we cannot find a ride.” . . . So we can’t do anything. So sometimes it is very hard. And sometimes . . . when I am supposed to come back home . . . if I’m supposed to leave at 3 o’clock and they’ll tell you, “No, we don’t have a ride available until 5:00, 5:30 or 6 o’clock.” So during that time, I have to wait three or four hours there [hospital] to come back home. (Participant 13)

Mothers who traveled with their children by public transit recounted the challenges they confronted. One mother described how public transportation was time consuming: “It was taking the bus . . . it takes two hours to get there and in the time spent there [at the appointment] and then two hours to get home . . .” (Participant 11).

Another mother felt that public transit was distressing for her child:

I think that public transport is faster than driving to get to [hospital] but it’s more difficult because my child with special needs . . . is not a big fan of people or people in their space or other things . . . so it’s really kind of difficult to take public transit. (Participant 12)

Category 2: Competing priorities for the child

This category represents the competing priorities that existed while trying to meet their children’s needs, including maintaining the scheduled appointments. Mothers’ accounts revealed that they were often required to make choices between attending appointments at the hospital and other priorities in their children’s lives. These priorities included the child’s physical health and medical needs, emotional well-being, and school and associated extracurricular activities.

Mothers explained that they were required to fit their child’s other care requirements around the appointment travel and time spent attending the appointment. For example, one mother explained how her child’s medication and eating schedule conflicted with a wheelchair accessible transit ride:

And sometimes, you know . . . before the ride (transit) comes and you try to give them something to eat . . . You have to fight, fight with them just to get something in their stomach before you get on. And sometimes when you try to give them . . . they take time eating . . . you cannot rush them to try and eat fast. And when they’re not eating you just feel like you’re begging them. It’s like; “please take something.” They can’t take medication on an empty stomach. (Participant 13)

Participants also described how appointment keeping was challenging when children were scheduled for multiple appointments. At times, mothers canceled appointments because they had appointments that were to occur in either the same setting (the rehabilitation hospital) or in a different setting. Mothers felt that they had no choice but to decide which appointment was more important to their child. For example, one mother, who missed an appointment at the feeding clinic in the rehabilitation hospital, explained her decision-making process:

So at the time, I missed an appointment at the feeding clinic to help with their eating but then I had . . . I think it was an assessment—a doctor’s appointment—to have a check-up on my child and see how they are doing and see if they are developing. So I figured it made more sense for me in terms of health . . . that was more important. (Participant 9)

Mothers’ accounts revealed that school attendance and participation in social and recreational activities were perceived as being essential to their children’s well-being, and thus choosing among competing priorities was challenging. Mothers reported that their children missed a lot of school because of appointments. At times, school and its related extracurricular activities were chosen over the appointment (by mothers and/or their children); two mothers explained:

Yeah we missed some of the appointments . . . if there were some school . . . there were some they could not take an absence that day . . . maybe something important is going on or something like that, then yes, we had to cancel. (Participant 9)

We participate in extracurricular activities too. So if there is some practice or something that day of the appointment, that is really preferred . . . we doesn’t want to miss it. (Participant 10)

Finally, mothers’ narratives consistently revealed that appointments were missed when their child had an acute illness such as a fever or cold. Many participants described this as “frustrating,” but that it was necessary to protect their child’s own health and the health of other children at the hospital.

Category 3: Competing priorities for family members

Mothers described the competing priorities that surfaced in the family environment because of their children’s appointments. They were often required to make choices between attending the appointments and other family responsibilities and commitments. These responsibilities included parents’ employment outside of the home and the needs of siblings and/or the family unit.

Participants who had multiple children described the challenges with appointment keeping and balancing the needs of the child’s siblings and/or the family unit. This included maintaining family time or family commitments outside of appointments, vacation time, and protecting siblings’ time. One mother explained how she minimized the child’s siblings’ time related to appointments at the hospital:

We’ve certainly given up blocks of appointments for this reason because my other children, as well . . . I don’t want them to spend so much time in a hospital. They also have to have time to go to do things and learn and whatever. (Participant 12)

The amount of time that was required for appointment attendance was conveyed as a barrier to appointment keeping as mothers were required to make many trade-offs between the appointment and other responsibilities such as employment and home and family obligations. For example, one mother explained the strict schedule that she had to follow to fit the appointment into both her child’s school and her work schedule:

You know, if I leave from my house, it probably takes me a half an hour during traffic. So I ask for the earliest appointment we can get, which is 8 o’clock. Which means I have to leave my house at 7:30 to get there for 8 o’clock so that I’m out of there [rehabilitation hospital] by 9:00. So I can drop my child off at preschool and I can get back to work for 10 or 10:30. (Participant 15)

Category 4: Provision of health care services

Mothers reported that barriers existed that contributed to the challenges that they and their children experienced during the scheduling and actual receipt of services. The lack of flexibility in the scheduling of appointments was frequently mentioned by mothers as being challenging. One mother described, “On this date you need to come. It’s not really a negotiation. It’s more like: you’re coming at this time” (Participant 2).

Because of this inflexibility, the available appointment times and dates did not always correspond with families’ schedules. For example, all of the mothers who were employed outside of the home described the conflict between being at their place of employment and being at their child’s appointments. This was especially pertinent to appointments that were booked within standard work hours. One, who was a single parent, explained,

The most difficult thing with missing appointments is that the clinicians work 9-5 just like most people do . . . not being able to book before regular hours especially for me being the sole caregiver . . . and I work full-time . . . it’s tough . . . I’m exhausted. (Participant 15)

Another explained how she took time from her employment to attend appointments: “The one thing I would say about the appointments, because I work part-time, I have to book a lot of days off work in advance to go or I have to make arrangements” (Participant 8).

Mothers also described the limitations in the scheduling approach. They reported that the clinics did not consistently have effective reminder notifications, that they had problems rescheduling appointments after nonattendance (long wait time for the next appointment), and erroneous scheduling or canceling by the hospital. One mother explained that a lack of communication between health care providers resulted in delayed appointment scheduling and care after her daughter’s hospitalization: “My child is hospitalized a lot so missed a lot (appointments) and then they kind of get forgotten” (Participant 14).

Participants described that they felt they were perceived negatively by hospital staff for having missed an appointment. In addition, they did not feel that hospital staff understood that they went to great efforts to attend appointments and that missing was frustrating for parents. One mother described how she believed that some staff at the hospital perceived her negatively:

It’s not like we would like to miss it. It’s just that our life is so busy that sometimes, we just can’t make it. So it would seem that they would hold that personal. So it makes us wonder: Is it because they get paid per appointment? Maybe we’re just ruining their day, kind of thing . . . so we feel responsible (Participant 8).

Another mother explained how she wanted the staff to appreciate the difficulty in attending appointments: “Because they [health care providers] are expecting that [the appointment] to be your top priority . . . which it is but there’s so many other things making a barrier to getting there” (Participant 14).

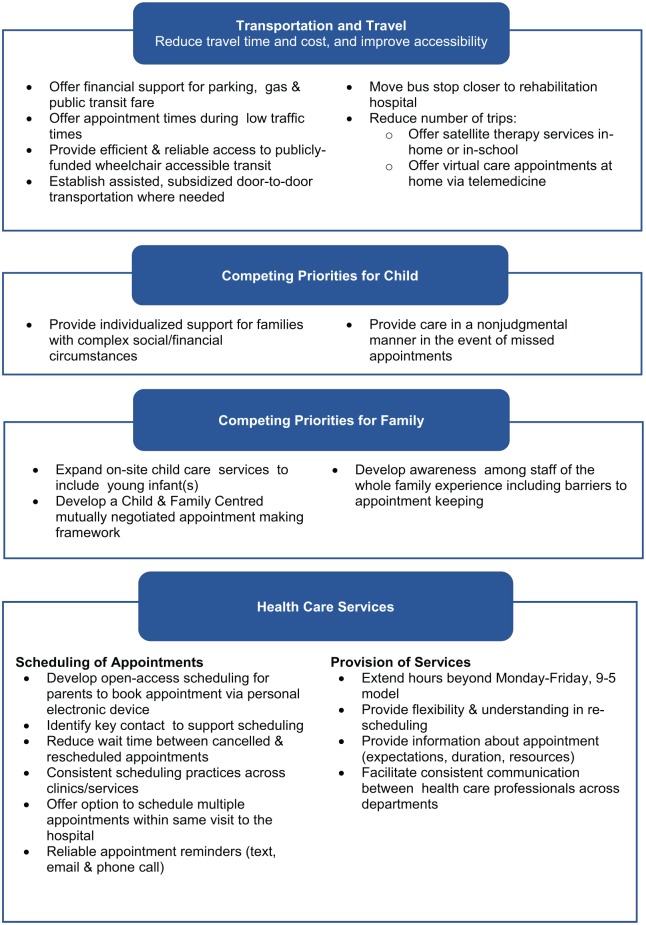

Appointment Keeping Recommendations

Mothers made several recommendations that they believed would assist families with appointment keeping and improve the experience around attending appointments at the rehabilitation hospital for children and families. Although mothers’ descriptions of barriers were provided with context details, their suggestions fell after these descriptions and were provided in more of a checklist format. As such, mothers’ recommendations are presented as a figure, without including direct quotations (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mothers’ recommendations for appointment keeping, by category.

Overall, mothers’ suggestions focused more heavily in the Transportation and Scheduling and Provision of Health Services categories. Within the Transportation category, mothers gave suggestions to reduce travel time, reduce costs, and to improve the efficiency and reliability of wheelchair accessible transportation. In addition, to reduce the number of trips to appointments, they recommended alternative methods and sites for the provision of services. Specifically, satellite locations and virtual care appointments would reduce or eliminate the need to travel so frequently to certain appointments.

Several ideas were provided to enable appointment keeping in the Health Services Provision category. The facilitators in this category focus on the scheduling of appointments and communication with health care professionals. In terms of scheduling, mothers suggested that parents be given more control by having the opportunity to self-schedule appointments via a computer or mobile device, that each family have one key contact person with whom they schedule appointments, and that more flexibility exist in rescheduling in the event that an appointment be canceled. Furthermore, all mothers reported that receiving consistent reminders via multiple modes of communication would be very helpful. In terms of service provision, mothers recommended consistent and regular communication across disciplines and departments regarding multiple appointments. Finally, information about the purpose and time expectations for individual appointments would assist with planning and expectations.

Both of the Competing Priorities Categories (Child and Family Priorities) represent mothers’ identification of the need for effective communication from health care providers and staff at the hospital. Mothers suggested that health care professionals consider the challenges that they confront in their home environment related to the care of their child who has CP and the subsequent work that is required to attend appointments. This empathy translates into health care providers providing nonjudgmental care to all families, irrespective of their appointment keeping history. Furthermore, assessing each family’s specific context, including their financial and social needs, was proposed. Finally, mothers suggested that the consideration of other family members would ensure onsite care of well siblings and recognition of other family members’ needs.

Discussion

This study explored mothers’ perceptions of the barriers and experiences around health care appointment keeping for their children with disabilities in a rehabilitation setting. Qualitative data captured the challenges that families encountered related to a group of children who had multiple disabilities permitting seminal contributions to our understanding. First, mothers’ accounts suggest that they encountered complex, multifaceted challenges and barriers to appointment keeping that are specific to children who have disabilities. Second, this open-ended approach allowed the opportunity for mothers to identify the contextual elements that could be modified to improve their experience when attending appointments and to facilitate appointment keeping. Although the provision of rehabilitation services delivered to children has evolved over time in terms of types of therapy offered and effective approaches, it is crucial to understand the impact of attending appointments on families and the implications for children’s overall well-being. Furthermore, in keeping with a family-centered theoretical underpinning and care context, eliciting parents’ perspectives may reduce unmet needs (Kuo, Frick, & Minkovitz, 2011) and encourage positive health outcomes in children who have special health care needs (Kuo, Bird, & Tilford, 2011).

Our study is unique in that, although some of the challenges identified in our study were also reported in previous empirical literature, the contexts within which mothers worked to transport their children to an appointment were fraught with complex priorities and needs of the child. Previous studies have investigated the reasons for appointment nonattendance across various settings (hospital, primary care, ambulatory clinic); however, there is scant literature relevant to the experience of children with disabilities in the rehabilitation setting. It is somewhat difficult to compare our specific findings with other studies, as the description of the labor-intensive context and resulting transportation barriers experienced by our families was more extensive than found in other studies. Furthermore, these studies did not include children who had multiple and complex disabilities. With these differences in mind, we discuss previous research herein to attempt to contextualize and highlight our results.

Perceived Barriers

In this study, mothers described many barriers associated with the transportation and travel to appointments. Previous studies have also reported transportation barriers to appointment keeping (Ballantyne et al., 2015; Cameron et al., 2014; Guzek et al., 2015; Samuels et al., 2015). However, while our study provides insight into the context surrounding these barriers, others cited general reports of transportation and/or parking difficulties.

We found that competing priorities of the child and the family were barriers to appointment keeping. In previous studies, scheduling conflicts with other medical appointments, school, and extracurricular studies were also reported (Ballantyne et al., 2015; Cameron et al., 2014; Hon et al., 2005; Samuels et al., 2015; Touch & Berg, 2016). In addition, similar to our findings, several other researchers reported that parental health and illness (Guzek et al., 2015; Samuels et al., 2015; Touch & Berg, 2016), employment and other commitments (Cameron et al., 2014; Guzek et al., 2015; Hon et al., 2005; Samuels et al., 2015; Touch & Berg, 2016), sibling schedule conflicts (Touch & Berg, 2016), and parent forgetting (Ballantyne et al., 2015; Guzek et al., 2015; Hon et al., 2005; Samuels et al., 2015) were barriers to attendance in other clinical settings. Financial circumstances and insurance support were also cited as barriers to attendance (Ballantyne et al., 2015; Guzek et al., 2015; Samuels et al., 2015; Touch & Berg, 2016) which we did not find. This may be due to the Canadian setting where all individuals have universal health insurance for health care services and our sample was not characterized primarily as low-income households.

Scheduling and service provision was a prominent category emerging from the data in our study. Some of the barriers that we identified are corroborated in the literature, including lack of flexibility in appointment time (Touch & Berg, 2016), long wait time between scheduling and the appointment date (Cameron et al., 2014; Hon et al., 2005; Samuels et al., 2015; Touch & Berg, 2016), and inadequate appointment reminders (Ballantyne et al., 2015; Cameron et al., 2014; Guzek et al., 2015). Inability to schedule multiple appointments consecutively was only identified in one other study (Touch & Berg, 2016).

Some researchers have identified parents’ perception of the necessity of the appointment as a key barrier to attendance (Cameron et al., 2014; Guzek et al., 2015; Hon et al., 2005; Samuels et al., 2015). In our study, this was reported minimally perhaps because the children had complex needs and required ongoing therapy; appointments in previous studies were based in either primary care or acute specialty services.

The body of relevant literature in this area of study has traditionally used language that may be interpreted as having a negative tone directed at parents: failure to attend, appointment nonattendance, missed appointments, and compliance with appointments (Ballantyne & Rosenbaum, 2017). The use of this language can send a message to parents that may perpetuate their feelings of guilt, and their feeling that they are negatively judged by health care providers. The use of more neutral language, such as appointment “keeping,” may minimize unnecessary distress on parents.

Appointment Keeping Recommendations

Asking mothers directly to recommend ways to improve an aspect of the health care system based on their extensive experience is a meaningful way to develop effective family-centered interventions and strategies to support the appointment experience. The facilitators suggested by mothers that addressed barriers in the Competing Priorities for Child and Family categories in our study focused on changes to the environment and services received by the child and family; that is, specific ways in which the hospital could assist to address the competing priorities of the entire family. In contrast, two previous qualitative studies, which also identified facilitators, focused on how parents themselves could facilitate attendance by addressing the competing priorities of the child and family. These two studies also identified that parents’ motivation to “improve the health of their child” facilitated appointment keeping (Cameron et al., 2014; Schneiderman et al., 2017). In addition, health care professionals were interviewed in one study where they suggested that educating parents about the importance of attending appointments and consequences of nonattendance could influence attendance (Cameron et al., 2014). These previous studies perpetuate the notion that parents are in control of all aspects of their environment and ultimately responsible for attendance or nonattendance at appointments. Alternatively, shifting the focus to how the health care system can adapt, engage, and support children and parents around their care and therapy promotes a positive, supportive, and family-centered environment that will ultimately lead to a better experience and potentially better outcomes.

Transportation support was noted as a facilitator to appointment keeping in two previous qualitative studies (Cameron et al., 2014; Schneiderman et al., 2017); however, the specific findings within the general category of transportation were different from our findings. Schneiderman et al. (2017) identified ease of parking, and having a car as facilitators, while Cameron et al. (2014) identified improved transport links as a facilitator. Comparing studies on transportation aspects may be difficult given that each study site would have its own associated geographical characteristics such as traffic patterns, weather patterns (snow or warm climate), access to public transit, and the location and characteristics of the health care facility of interest. For example, while bad winter weather was a problem in our study, these previous studies were conducted in the United Kingdom and in a warm State in the United States, where snow and other winter driving conditions may not be as relevant.

Several recommendations addressing scheduling and the provision of health services reported herein were supported by findings in the existing literature. Three of the aforementioned qualitative studies identified reminders as a facilitator to appointment keeping (Cameron et al., 2014; Schneiderman et al., 2017; Touch & Berg, 2016). Similar to our study, two studies identified flexibility in appointment times (e.g., evening clinics) and the ability to combine multiple appointments (Cameron et al., 2014; Touch & Berg, 2016). Furthermore, the opportunity to seek information from health care providers was identified as a service delivery facilitator (Schneiderman et al., 2017).

Mothers in our study suggested alternative sites and service delivery models of care such as virtual care approaches that allows health care professionals to provide health services to families who cannot attend in person. Health services become more accessible and remotely available using mobile computing and communication health technologies (Free et al., 2013; Hasvold & Wootton, 2011) and telemedicine monitoring for children with complex needs (Nkoy et al., 2019). Mothers also recommended expanded service hours; a pilot study is currently underway to implement and evaluate the effectiveness of expanded evening and weekend clinic hours at the recruitment site.

Limitations

Our study sample was recruited from one setting and, therefore, may not be representative of the general population of mothers of children with CP. Furthermore, the participants tended to have higher incomes and the majority were two-parent families. However, the recruitment site exists in an ethnically diverse city. Furthermore, this sample was relatively heterogeneous with respect to age, education, and socioeconomic status. Women are more likely to participate in health care research and are more likely to be present with their child during clinic visits and therefore easier to recruit into studies (Macdonald, Chilibeck, Affleck, & Cadell, 2010). This poses a limitation with respect to the perspectives and findings drawn from the data, as they may not reflect the perspectives of a paternal parent.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to explore the experiences of appointment keeping within a pediatric rehabilitation setting. This population of children has unique challenges including comorbid diagnoses (such as CP and autism) which may contribute to the challenges of appointment keeping. Findings of this study suggest that challenges related to appointment keeping for this population are multifaceted and require further considerations by rehabilitation service providers. Interventions designed to target the identified challenges to appointment keeping are required to ensure that children receive the full range of services that are intended to benefit them. In addition, further development and evaluation of guidelines around financial and social support to family caregivers of children with complex health care needs at the policy level would ensure support in the management and practice contexts.

Conclusion

This study sought to gain an in-depth understanding of mothers’ perspectives, including barriers to pediatric outpatient appointments and associated facilitators. An in-depth analysis of these factors is important to develop greater awareness and understanding of the complex factors that surround appointment keeping. Findings from this study contribute to the research literature in childhood disability in health care rehabilitation and outpatient settings, as well as to the broader literature on providing family-centered care. Key findings suggest that rehabilitation settings should consider unique strategies such as transportation support, multimethod scheduling options (e.g., open access scheduling, key contact, extended service hours, and appointment reminders), and enhanced family-centered care delivery approaches to improve the experience and scheduling for children. The evidence gained from this research can be used to inform the development of strategies and recommendations to better meet the needs of families who experience multifaceted attendance barriers, thereby promoting access for this population of children. Health care organizations would benefit from gaining an appreciation of the difficulties these children and families face related to appointment keeping, and in turn, help to promote a more supportive and engaging rather than a judgmental care environment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank each of the participants who dedicated their time to participating and sharing their thoughts in the interviews. We also thank Family Leaders at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital for their expert guidance on the study design and input into the semi-structured interview guide, the clinicians and Abigail Arku-Matey for recruitment support, and Denise Guerriere for editing support.

Author Biographies

Marilyn Ballantyne, RN, PhD, is a clinician investigator and chief nursing executive at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital/Bloorview Research Institute in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Laurie Liscumb, RN, BScN, is an ambulatory care nurse at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Erin Brandon, RN(EC), MN, is a nurse practitioner (NP) in the Complex Care NP-led Clinic and Rett Syndrome Pathway Clinic at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Janice Jaffar, HBSc, is the intake coordinator for Ambulatory Care at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Andrea Macdonald, MS, MBA, Reg. CASLPO, CHE, is an operations manager for Ambulatory Care at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Laura Beaune, MSW, Res. Dip, is a clinical research coordinator at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the Center for Leadership in Child Development Project Funding Grant, Bloorview Research Institute, Toronto, Canada.

ORCID iD: Marilyn Ballantyne  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4003-7126

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4003-7126

References

- Anwar T., Cooper C. S., Gerard L. L., Storm D. W. C. (2017). Factors affecting missed appointments in a pediatric urology outpatient clinic. Urology Practice, 4, 290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.urpr.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai L., Stapley S., Roberts H. (2014). “Did not attends” in children 0-10: A scoping review. Child: Care, Health and Development, 40, 797–805. doi: 10.1111/cch.12111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne M., Benzies K., Rosenbaum P., Lodha A. (2015). Mothers’ and health care providers’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to attendance at Canadian neonatal follow-up programs. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41, 722–733. doi: 10.1111/cch.12202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne M., Rosenbaum P. L. (2017). Missed appointments: More complicated than we think. Paediatrics and Child Health, 22, 164–165. doi: 10.193/pch/pxx039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne M., Stevens B., Guttmann A., Willan A. R., Rosenbaum P. (2014). Maternal and infant predictors of attendance at neonatal follow-up programmes. Child: Care, Health and Development, 40, 250–258. doi: 10.1111/cch.12015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman J. A., Conaway M. R. (2014). Adolescents with cerebral palsy: Transitioning to adult health care services. Clinical Pediatrics, 53, 356–363. doi: 10.1177/0009922813510203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyartzis R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron E., Heath G., Redwood S., Greenfield S., Cummins C., Kelly D., Pattison H. (2014). Health care professionals’ views of paediatric outpatient non-attendance: Implications for general practice. Family Practice, 31, 111–117. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain M. A., Kent R. M. (2005). The needs of young people with disabilities in transition from paediatric to adult services. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 41, 111–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chariatte V., Berchtold C., Akré C., Michaud P., Suris J. (2008). Missed appointments in an outpatient clinic for adolescents, an approach to predict the risk of missing. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43, 38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chariatte V., Michaud P., Berchtold A., Akré C., Suris J. (2007). Missed appointments in an adolescent outpatient clinic: Descriptive analyses of consultations over eight years. Swiss Medical Weekly, 137, 677–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. D., Goldbart A. D., Levi I., Shapiro J., Vardy D. A. (2007). Health provider factors associated with nonattendance in pediatric dermatology ambulatory patients. Pediatric Dermatology, 24, 113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00354.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordiner D., Logie L., Becher J. C. (2010). To see or not to see? . . . that is the question. An analysis of out-patient follow-up arrangements and non-attendance in a community paediatric population. Scottish Medical Journal, 55, 17–19. doi: 10.1258/rsmsmj.55.1.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas L. F., Fleck J. L., Oliveira F. L. C., Hamacher S. (2018). No-shows in appointment scheduling: A systematic literature review. Health Policy, 122, 412–421. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drieher J., Goldbart A., Hershkovich J., Vardy D. A., Cohen A. D. (2008). Factors associated with non-attendance at pediatric allergy clinics. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 19, 559–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00691.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Free C., Phillips G., Watson L., Galli L., Felix L., Edwards P., . . .Haines A. (2013). The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 10(1), e1001363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbart A. D., Dreiher J., Vardy D. A., Alkrinawi S., Cohen A. D. (2009). Nonattendance in pediatric pulmonary clinics: An ambulatory survey. BMC Pulmonary Medicine, 9(1), Article 12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M., Antshel K. M., Lewandowski L., Seiger D. (2010). Economic grand rounds: Predictors of missed appointments over the course of child mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services, 61, 657–659. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.7.657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzek L. M., Fadel W. F., Golomb M. R. (2015). A pilot study of reasons and risk factors for “no-shows” in a pediatric neurology clinic. Journal of Child Neurology, 30, 1295–1299. doi: 10.1177/0883073814559098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasvold P. E., Wootton R. (2011). Use of telephone and SMS reminders to improve attendance at hospital appointments: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 17, 358–364. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2011.110707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon K. L. E., Leung T. F., Wong Y., Ma K. C., Fok T. F. (2005). Reasons for new referral non-attendance at a pediatric dermatology center: A telephone survey. Journal of Dermatological Treatment, 16, 113–116. doi: 10.1080/09546630510027877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Hanauer D. A. (2014). Patient no-show predictive model development using multiple data sources for an effective overbooking approach. Applied Clinical Informatics, 5, 836–860. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2014-04-RA-0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys L., Hunter A. G. W., Zimak A., O’brien A., Korneluk Y., Cappelli M. (2000). Why patients do not attend for their appointments at a genetics clinic. Journal of Medical Genetics, 37, 810–815. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.10.810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. E., Krishnaswami S., McPheeters M. (2011). Unmet health care needs in children with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 2714–2723. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalb L. G., Freedman B., Foster C., Menon D., Landa R., Kishfy L., Law P. (2012). Determinants of appointment absenteeism at an outpatient pediatric autism clinic. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 33, 685–697. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31826c66ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo D. Z., Bird T. M., Tilford J. M. (2011). Associations of family-centered care with health care outcomes for children with special health care needs. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15, 794–805. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0648-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo D. Z., Frick K. D., Minkovitz C. S. (2011). Association of family-centered care with improved anticipatory guidance delivery and reduced unmet needs in child health care. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15, 1228–1237. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0702-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberth E. F., Rothstein E. P., Hipp T. J., Souder R. L., Kennedy T. I., Faccenda D. F., . . .Homeier B. P. (2002). Rates of missed appointments among pediatric patients in a private practice: Medicaid compared with private insurance. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156, 86–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1985). Establishing trustworthiness. In Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (Eds.), Naturalistic Inquiry (pp. 289–331). Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald M. E., Chilibeck G., Affleck W., Cadell S. (2010). Gender imbalance in pediatric palliative care research samples. Palliative Medicine, 24, 435–444. doi: 10.1177/0269216309354396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majnemer A., Shikako-Thomas K., Lach L., Shevell M., Law M., Schmitz N., . . . QUALA Group. (2014). Rehabilitation service utilization in children and youth with cerebral palsy. Child: Care, Health and Development, 40, 275–282. doi: 10.1111/cch.12026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallow J. A., Theeke L. A., Barnes E. R., Whetsel D., Mallow B. K. (2014). Free care is not enough: Barriers to attending free clinic visits in a sample of uninsured individuals with diabetes. Open Journal of Nursing, 4, 912–919. doi: 10.4236/ojn.2014.413097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz J. T., Volkening K., Laffel L. M. B. (2014). Care utilization in a pediatric diabetes clinic: Cancellations, parental attendance, and mental health appointments. The Journal of Pediatrics, 164, 1384–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod H., Heath G., Cameron E., Debelle G., Cummins C. (2015). Introducing consultant outpatient clinics to community settings to improve access to paediatrics: An observational impact study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 24, 377–384. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkoy F. L., Hofmann M. G., Stone B. L., Poll J., Clark L., Fassl B. A., Murphy N. A. (2019). Information needs for designing a home monitoring system for children with medical complexity. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 122, 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Pesata V., Pallija G., Webb A. A. (1999). A descriptive study of missed appointments: Families’ perceptions of barriers to care. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 13, 178–182. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5245(99)90037-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina P., O’Donnel M., Rosenbaum P., Brehaut J., Walter S. D., Russel D., . . .Wood E. (2005). The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics, 115, e626–e636. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum P., Paneth N., Leviton A., Goldstein M., Bax M., Damiano D., . . .Jacobsson B. (2007). A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 109, 8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.tb12610.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels R. C., Ward V. L., Melvin P., Macht-Greenberg M., Wenren L. M., Yi J., . . .Cox J. E. (2015). Missed appointments: Factors contributing to high no-show rates in an urban pediatrics primary care clinic. Clinical Pediatrics, 54, 976–982. doi: 10.1177/0009922815570613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23, 334–340. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman J. U., Kennedy A. K., Sayegh C. S. (2017). Qualitative study of foster caregivers’ views on adherence to pediatric appointments. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 31, 104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22, 63–75. doi: 10.3233/EFI-2004-22201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman M. L., Barnum D. D., Buhman-Wiggs A., Nyberg E. (2009). Clinical intake of child and adolescent consumers in a rural community mental health center: Does wait-time predict attendance? Community Mental Health Journal, 45, 78–84. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9153-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tin W., Fritz S., Wariyar U., Hey E. (1998). Outcome of very preterm birth: Children reviewed with ease at 2 years differ from those followed up with difficulty. Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 79, F83–F87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touch J., Berg J. P. (2016). Parent perspectives on appointment nonattendance: A descriptive study. Pediatric Nursing, 42, 181–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon E. Y., Davis M. M., Cleave J. V., Maheshwari S., Cabana M. D. (2005). Factors associated with non-attendance at pediatric subspecialty asthma clinics. Journal of Asthma, 42, 555–559. doi: 10.1080/02770900500215798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young N. L., Gilbert T. K., McCormick A., Ayling-Campos A., Boydell K., Law M., . . .Williams J. I. (2007). Youth and young adults with cerebral palsy: Their use of physician and hospital services. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88, 696–702. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]