Respiratory infection by pathogens via aerosol remains a major concern for both natural disease transmission as well as intentional release of biological weapons. Critical to understanding the disease course and pathogenesis of inhaled pathogens are studies in animal models conducted under tightly controlled experimental settings, including the inhaled dose. The route of administration, particle size, and dose can affect disease progression and outcome. Damage to or loss of pathogens during aerosolization could increase the dose required to cause disease and could stimulate innate immune responses, altering outcome. Aerosol generators that reduce pathogen loss would be ideal. This study compares two aerosol generators to determine which is superior for animal studies. Aerosol research methods and equipment need to be well characterized to optimize the development of animal models for respiratory pathogens, including bioterrorism agents. This information will be critical for pivotal efficacy studies in animals to evaluate potential vaccines or treatments against these agents.

KEYWORDS: aerosol, bacteriology, infectious disease, respiratory pathogens, virology

ABSTRACT

Experimental infection of animals with aerosols containing pathogenic agents is essential for an understanding of the natural history and pathogenesis of infectious disease as well as evaluation of potential treatments. We evaluated whether the Aeroneb nebulizer, a vibrating mesh nebulizer, would serve as an alternative to the Collison nebulizer, the “gold standard” for generating infectious bioaerosols. While the Collison possesses desirable properties that have contributed to its longevity in infectious disease aerobiology, concerns have lingered about the liquid volume and concentration of the infectious agent required to cause disease and the damage that jet nebulization causes to the agent. Fluorescein salt was added to the nebulizer contents to assess pathogen loss during aerosolization. Relative to fluorescein salt, loss of influenza virus during aerosolization was worse with the Collison than with the Aeroneb. Four other viruses also had superior aerosol performance with the Aeroneb. The Aeroneb did not improve the aerosol performance for a vegetative bacterium, Francisella tularensis. Environmental parameters collected during the aerosol challenges indicated that the Aeroneb generated a higher relative humidity in exposure chambers while not affecting other environmental parameters. The aerosol mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) was generally larger and more disperse for aerosols generated by the Aeroneb than what is seen with the Collison, but ≥80% of particles were within the range that would reach the lower respiratory tract and alveolar regions. The improved aerosol performance and generated particle size range suggest that for viral pathogens, the Aeroneb is a suitable alternative to the Collison three-jet nebulizer for use in experimental infection of animals.

IMPORTANCE Respiratory infection by pathogens via aerosol remains a major concern for both natural disease transmission as well as intentional release of biological weapons. Critical to understanding the disease course and pathogenesis of inhaled pathogens are studies in animal models conducted under tightly controlled experimental settings, including the inhaled dose. The route of administration, particle size, and dose can affect disease progression and outcome. Damage to or loss of pathogens during aerosolization could increase the dose required to cause disease and could stimulate innate immune responses, altering outcome. Aerosol generators that reduce pathogen loss would be ideal. This study compares two aerosol generators to determine which is superior for animal studies. Aerosol research methods and equipment need to be well characterized to optimize the development of animal models for respiratory pathogens, including bioterrorism agents. This information will be critical for pivotal efficacy studies in animals to evaluate potential vaccines or treatments against these agents.

INTRODUCTION

Experimental infection of animals with aerosolized pathogens to study pathogenesis or evaluate medical countermeasures remains a complicated procedure that requires expert training and highly sophisticated equipment. Environmental and situational factors can affect the survival, dose, site of deposition, and virulence of pathogenic agents (1–4). For example, studies have shown that relative humidity (RH) inside the chamber can alter aerosolization of bacteria and viruses (3, 5–7). Particle size can affect where a pathogen lands in the respiratory tract, which can have dramatic effects on pathogenesis and virulence (1, 2, 4, 8, 9). Therefore, to achieve reproducible dosing between experiments, one must fully characterize and validate all parameters of an aerosol exposure.

Aerosol performance can be affected by a variety of different factors, from preaerosolization factors, such as pathogen growth conditions, to selection of equipment, such as the exposure chamber used, to postprocessing factors, such as concentration determination (3, 5, 10, 11). Thus, prior to beginning aerosol studies with animal models, it is important to characterize and understand the impact of aerosol equipment selection, pathogen-handling techniques, and environmental parameters on the reproducibility of a research design (24). The Collison three-jet nebulizer has long been used as the “gold standard” for infectious disease aerobiology studies because of its ease of use and relatively monodisperse particle size that can reach the deep lung of rodents, ferrets, rabbits, and nonhuman primates (Fig. 1A) (12). The nebulizer utilizes Bernoulli’s principle to shear a liquid suspension into aerosolized particles, which impact against a hard surface (the interior of the jar) to further break apart particles (12). A primary reason for the appeal of the Collison nebulizer is that it generates high concentrations of particles that are relatively monodisperse, with a mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) of between 1 and 2 μm (13). Particles of this size can reach the alveolar regions of the lung. However, the method by which aerosols are generated by the Collison has been considered “harsh” and could damage microorganisms, impacting the dose required to cause infection/disease and the host response to infection (14, 15). Damaged bacteria or viruses may also stimulate immune responses that protect the host. These effects could raise the dose required to cause disease, thereby requiring large quantities of pathogens grown to high titers for aerosol experiments. The Collison also requires a relatively high volume of challenge material (10 ml), which can be difficult to generate depending on the agent and nebulizer concentration needed to achieve a desired challenge dose. These deficiencies can be a substantial impediment to aerosol studies, particularly for pathogens that require a high challenge dose to achieve infection/disease (e.g., alphaviruses in macaques). Alternative nebulizers that generate small particles that would penetrate to the deep lung (≤5 μm), are less harsh on the microorganism being aerosolized, and require less challenge material to achieve comparable or higher doses would be desirable.

FIG 1.

Collison and Aeroneb aerosol generators. The Collison nebulizer by CH Technology (left) utilizes Bernoulli’s principle to create aerosols from a recirculated liquid sample. The Aeroneb by Aerogen (right) utilizes a vibrating palladium mesh membrane to create aerosols from a liquid sample.

The Aerogen Solo nebulizer (also known as Aeroneb) is a single-use nebulizer employed in clinical settings for the delivery of aerosolized medication (16). The Aeroneb utilizes a palladium mesh perforated with conical holes that act as a micropump when vibrated, rather than high-velocity airflow (17). We hypothesized that the Aeroneb might put less mechanical stress on pathogens than the Collison, potentially leading to improved aerosol performance. We report our efforts to characterize the aerosol performance of the Aeroneb compared to that of the Collison for bacterial (Francisella tularensis) and viral (influenza virus) pathogens. Francisella tularensis is a select agent which causes severe disease when spread through the respiratory route. Influenza virus is a common respiratory pathogen with the potential to cause high morbidity and mortality rates. We evaluated performance across a range of exposure chambers. Because our data with influenza virus suggested that the Aeroneb generated higher aerosol concentrations than the Collison, we also evaluated the Aeroneb for other viruses, including alphaviruses and Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV). There is concern that alphaviruses or Rift Valley fever virus could be used as a biological weapon, which would most likely be disseminated by aerosol in an attack seeking to generate mass casualties.

Spray factor (SF), the ratio of the concentration of the agent in the aerosol to the concentration of the agent in the nebulizer, is commonly used in aerobiology studies to evaluate aerosol performance (3–5, 13, 18, 19). (This and other abbreviations are defined in Table 1.) The impact of all aspects of aerosol generation, including the choice of aerosol generator, sampling device, and environmental parameters, on aerosol performance can be assessed using SF. A less commonly used alternative to SF is aerosol efficiency (AE), which compares the concentration of the agent aerosolized to the theoretical concentration of the agent aerosolized (20). In addition to SF and AE, in some experiments with pathogenic agents, we added fluorescein salt to the nebulizer as a comparator. Fluorescein should not be affected by mechanical stress caused by the aerosol generator, so the fluorescein SF represents a theoretical maximum aerosol performance at a given nebulizer concentration. In these studies, a decrease in the SF of infectious agents relative to the fluorescein SF in the same sample is assumed to be due to a decrease in pathogen viability resulting from mechanical stress caused by the nebulizer.

TABLE 1.

List of abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| AE | Aerosol efficiency (actual aerosol concn/theoretical aerosol concn) |

| BHI | Brain heart infusion |

| EEEV | Eastern equine encephalitis virus |

| FWB | Ferret whole body |

| LVS | Live vaccine strain |

| MMAD | Mass median aerodynamic diameter |

| NHP HO | Nonhuman primate head only |

| NOT | Nose-only tower |

| RVFV | Rift Valley fever virus |

| RWB | Rodent whole body |

| SF | Spray factor (aerosol concn/nebulizer concn) |

| VEEV | Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus |

| WEEV | Western equine encephalitis virus |

RESULTS

Aerosolization of viruses.

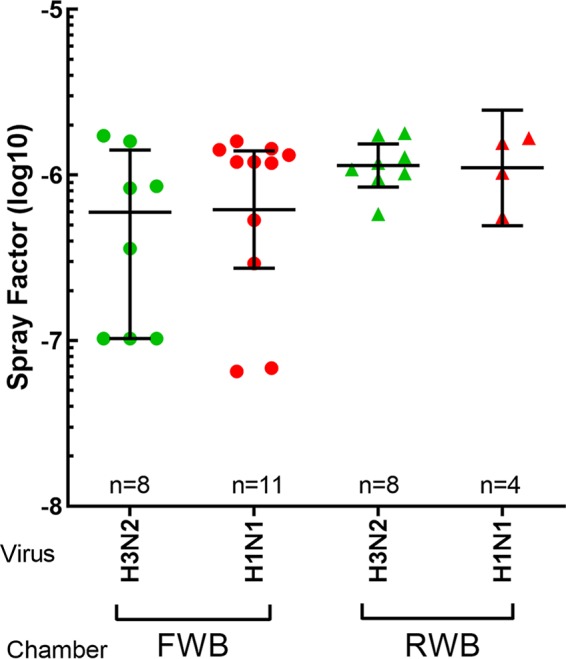

Prior to comparing nebulizers, we first sought to determine whether there was a difference in aerosol performances of H3N2 and H1N1 influenza viruses in the ferret whole-body (FWB) or rodent whole-body (RWB) chambers with the Collison nebulizer (Fig. 2). No significant differences were seen between the SFs of H1N1 and H3N2, regardless of the chamber used (FWB, P = 0.6711; RWB, P = 0.9333). Influenza virus SFs were slightly higher in the RWB than in the FWB chamber, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.3003). The H1N1 data included aerosols with A/Ca/4/09 or A/PR/8/34; no significant differences existed between the two isolates based on a two-sided Mann-Whitney test (P = 0.0901). In other experiments using other chambers and nebulizers, no differences in SF were seen based on the choice of influenza virus subtype, strain, or method of propagation (eggs or cell culture); the results in Table 2 and Fig. 3 show combined results for all influenza viruses.

FIG 2.

SF does not vary between influenza A virus strains. H3N2 and H1N1 influenza viruses were aerosolized using a Collison nebulizer into either an FWB or RWB exposure chamber. The graph shows SFs for each combination of virus and exposure chamber. Values shown are for individual aerosol runs, along with the means and standard deviations. None of the results were statistically significantly different as determined by a Mann-Whitney U test (FWB, P = 0.6711; RWB, P = 0.9333).

TABLE 2.

Aerosol performance of influenza virus strains using the Collison and Aeroneb in different exposure chambersa

| Chamber | Aerosol generator | Median fluorescein SF | Median influenza virus SF | Log reduction | Median influenza virus AE (%) | Avg RH (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOT | Collison | 3.44E−06 | 4.34E−06 | −0.10 | 13.87 | 85.83 |

| Aeroneb | 2.68E−06 | 1.18E−06 | 0.36 | 2.10 | 87.22 | |

| FWB | Collison | 6.35E−06 | 1.20E−06 | 0.72 | 6.84 | 61.21 |

| Aeroneb | 6.73E−06 | 5.80E−06 | 0.06 | 31.91 | 66.64 | |

| NHP HO | Collison | 5.07E−06 | 1.13E−06 | 0.65 | 5.35 | 81.15 |

| Aeroneb | 9.97E−06 | 7.52E−06 | 0.12 | 32.27 | 97.95 | |

Shown are the SF of fluorescein salt (the comparator), the SF of influenza virus, the log reduction in SF between fluorescein and influenza virus, and the aerosol efficiency. Average relative humidity is included to show that differences in SFs are most likely not due to this factor.

FIG 3.

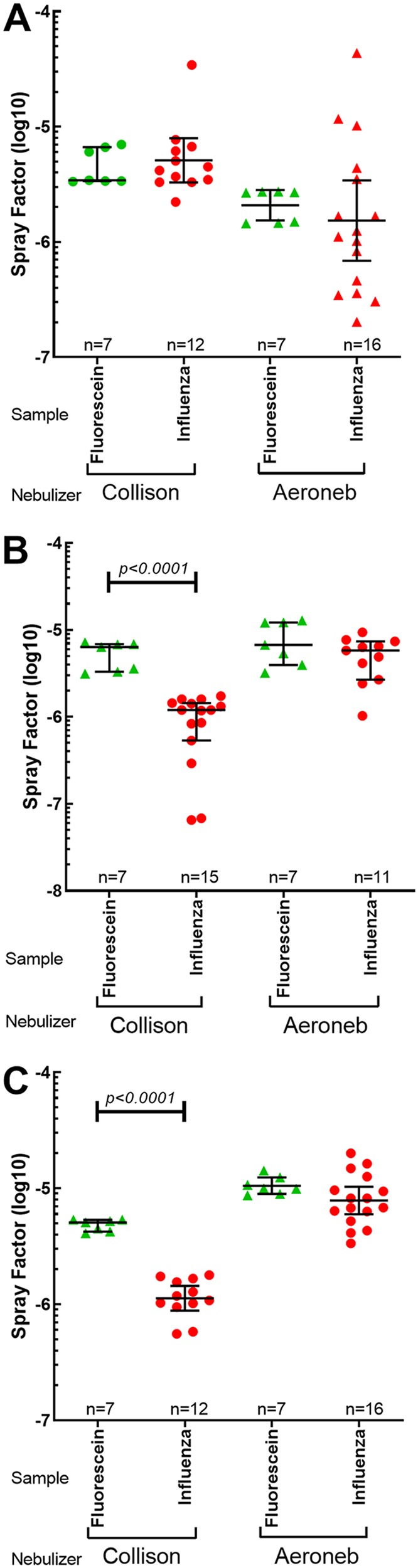

Less pathogen loss using the Aeroneb with influenza viruses. Graphs show the SFs of fluorescein salt and influenza virus in the NOT (A), FWB (B), and NHP HO (C) chambers using the Collison or the Aeroneb. Values shown are for individual aerosol runs, with means and standard deviations. Black horizontal bars indicate results that are statistically different between fluorescein salt and influenza SFs, determined using a Mann-Whitney U test, with the P values shown above the bars.

Comparison of aerosol performances of influenza virus strains between the Collison and Aeroneb was done using the rodent nose-only tower (NOT), the FWB chamber, and the nonhuman primate head-only (NHP HO) chamber. In the NOT, the SF for influenza virus was higher with the Collison, and this difference was significant (P = 0.0145) (Table 2 and Fig. 3A). The range of influenza virus SFs generated by the Aeroneb in the NOT was also substantially broader than that seen with other nebulizer-chamber combinations (coefficient of variation of 2.09). For both the Collison and Aeroneb in the NOT, there was little or no loss when comparing influenza virus SF to fluorescein SF. In contrast, in both the FWB and NHP HO chambers, the Aeroneb outperformed the Collison, as measured by SF and AE (P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Furthermore, there was a significant decrease in SFs between the fluorescein salt and influenza virus with the Collison in both the FWB and NHP HO chambers (P < 0.0001 for both) (Fig. 3B and C). This drop was not seen with the Aeroneb, suggesting that there is a considerable loss of viable influenza virus in aerosols generated by the Collison but not the Aeroneb in these chambers. Comparison of SFs between the NOT, FWB, and NHP HO chambers showed that they were also significantly different for both the Collison and the Aeroneb based on a Kruskal-Wallis test (P < 0.0001 for both).

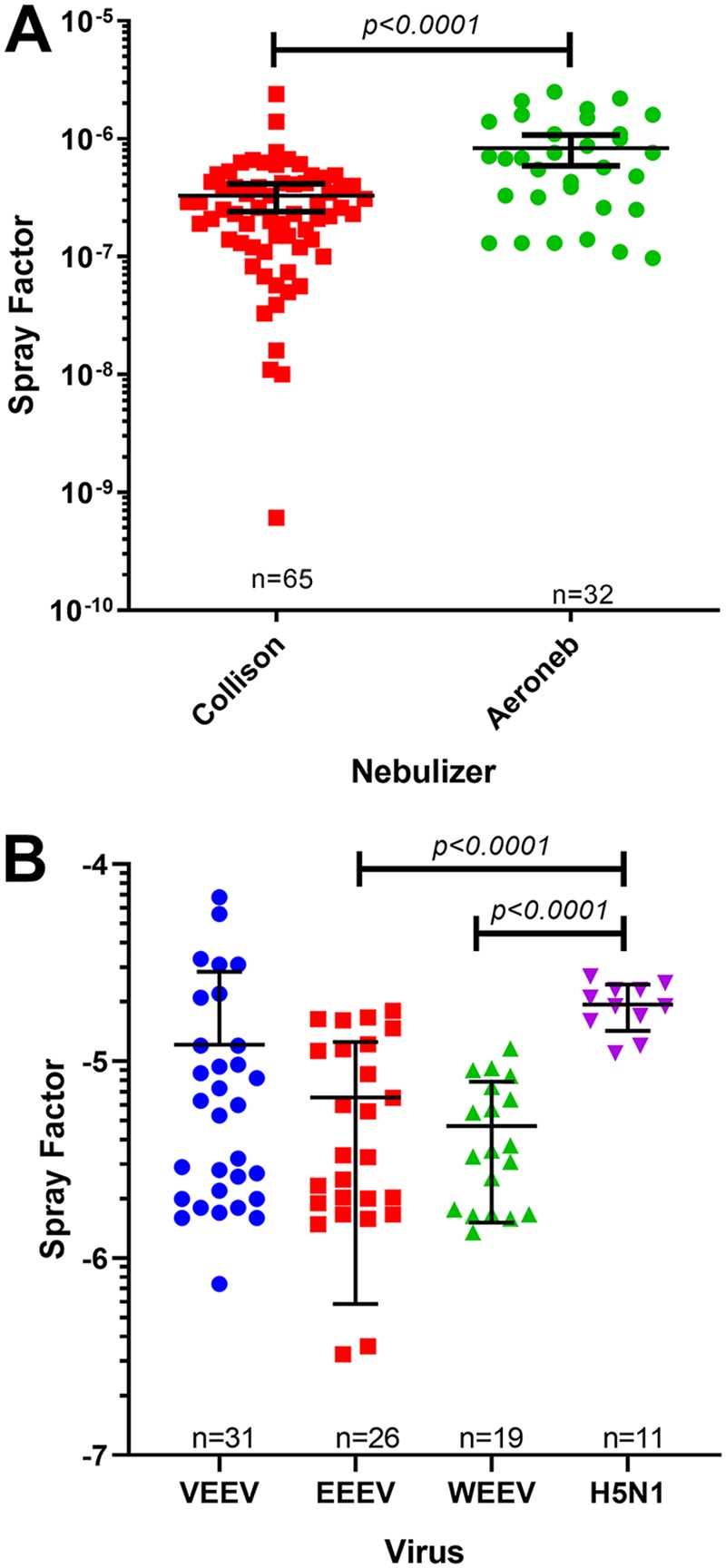

To evaluate whether these results were limited to influenza viruses, we also generated aerosols of RVFV into an RWB chamber and compared results obtained with the Aeroneb to prior data obtained with the Collison. As shown in Fig. 4A, the Aeroneb generated a higher SF of RVFV, and the improvement was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). For the encephalitic alphaviruses, the Aeroneb was used to generate aerosols in an NHP HO chamber (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Aerosol performance of the Aeroneb with other viral pathogens. Graphs show the SFs of RVFV with the Collison and the Aeroneb (A) and encephalitic alphaviruses and H5N1 using the Aeroneb (B). Values shown are for individual aerosol runs, with means and standard deviations. Black horizontal bars indicate results that are statistically different between fluorescein salt and influenza virus SFs, determined using a Mann-Whitney U test, with the P values shown above the bars.

Aerosolization of vegetative Gram-negative bacteria.

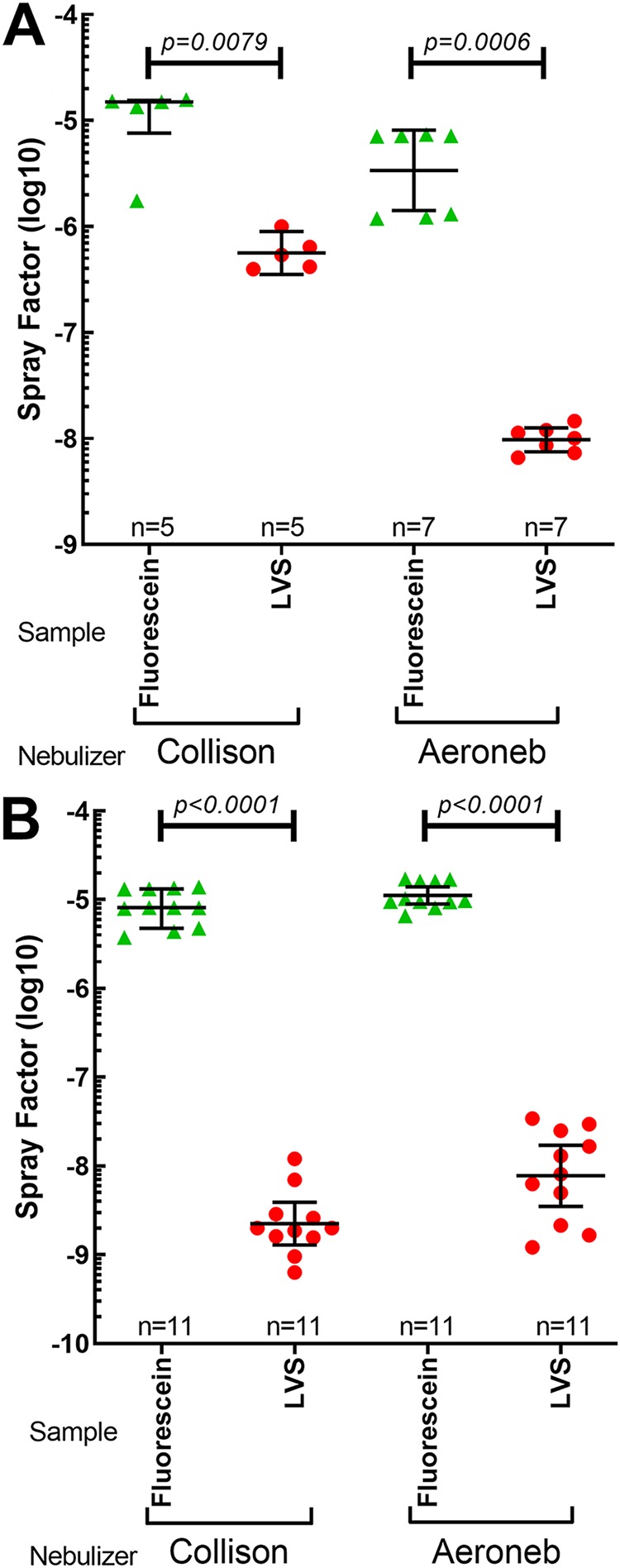

After demonstrating the improvement in SF for viral pathogens with the Aeroneb, we sought to determine whether similar improvements would be seen with a vegetative bacterium. We had previously shown that there was no difference in SFs between attenuated (LVS, the live vaccine strain) and virulent (SCHU S4) strains of F. tularensis (3). In those studies, we also found that the broth media used to propagate F. tularensis greatly impacted SF, as did the relative humidity (RH) in the chamber. Aerosol performance of brain heart infusion (BHI) broth-grown LVS with the Aeroneb and Collison was assessed in the NOT and the RWB chambers without supplemental humidification. In the NOT, the Collison generated a better SF and higher AE for LVS than did the Aeroneb; this difference was significant (P < 0.0001) (Table 3 and Fig. 5). In contrast, in the RWB chamber, the Aeroneb had a slightly better SF than the Collison, which also was significant (P = 0.0004). The AE was also higher for the Aeroneb than for the Collison in the RWB chamber. When comparing the LVS SF to the fluorescein SF in the NOT, we saw a significant, 2- to 3-log10 decrease in the SF of LVS with both the Collison and the Aeroneb (P = 0.0079 and 0.0006, respectively) (Fig. 5A). An even more substantial decrease in the LVS SF compared to the fluorescein SF was seen in the RWB chamber for both nebulizers (P < 0.0001 for both) (Fig. 5B). This suggests that both nebulizers cause a considerable loss of viable LVS bacteria, although the impact is smaller in the NOT. This is likely due to the high RH achieved in the NOT. The higher RH generated by the Aeroneb in the RWB chamber could also explain the superior LVS SF obtained with the Aeroneb in that chamber, as we have previously seen that raising the RH above 60% improves the LVS SF substantially (3). Comparison of SFs between the NOT and the RWB chambers showed a significant difference for the Collison but not the Aeroneb based on a Kruskal-Wallis test (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.4475, respectively).

TABLE 3.

Aerosol performance for LVS strains using the Collison and Aeroneb in different exposure chambersa

| Chamber | Aerosol generator | Median fluorescein SF | Median influenza virus SF | Log reduction | Median influenza virus AE (%) | Avg RH (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOT | Collison | 1.50E−05 | 5.4E−07 | 1.44 | 1.598 | 82.56 |

| Aeroneb | 7.08E−06 | 1.01E−08 | 2.85 | 0.035 | 78.81 | |

| RWB | Collison | 8.14E−06 | 2.01E−09 | 3.61 | 0.012 | 58.33 |

| Aeroneb | 9.74E−06 | 8.12E−09 | 3.08 | 0.108 | 69.21 | |

Shown are the SF of fluorescein salt (the comparator), the SF of LVS, the log reduction in SF between fluorescein and LVS, and the aerosol efficiency for the different generators and exposure chambers tested. Average relative humidity is included to show that differences in SFs are most likely not due to this factor.

FIG 5.

The Collison results in less pathogen loss than the Aeroneb. Shown are the SFs of fluorescein salt and LVS in the NOT (A) and RWB (B) chambers using the Collison or the Aeroneb. Values shown are for individual aerosol runs, with means and standard deviations. Black horizontal bars indicate results that are statistically different between fluorescein salt and influenza virus SFs, determined using a Mann-Whitney U test, with the P values shown above the bars.

Particle sizes generated by the Collison and Aeroneb.

The Collison has been shown to generate a small (MMAD of 1 to 2 μm) particle that is relatively monodisperse. These particles would reach the lower respiratory tract, including the alveolar regions. The information from the manufacturer of the Aeroneb indicates that it would generate a somewhat larger particle (average of 3.1 μm), which should also reach the alveolar regions. Using an APS 3321 instrument, we evaluated particle sizes generated by the Collison and Aeroneb in the different chambers. Initially, we used small (400- or 900-nm) microspheres; however, the Aeroneb was not able to generate good, consistent aerosols with these microspheres. We believe that this difficulty was a result of the microspheres clumping and not being able to readily pass through the vibrating mesh; however, mild sonication did not measurably improve the results (data not shown). If larger particles cannot readily pass through the vibrating mesh, this may contribute to the lower SF obtained for LVS with the Aeroneb. For this reason, we used fluorescein instead of microspheres to measure particle size. The results are shown in Table 4. Particle sizes obtained for the Collison were larger than expected, which we believe may be due to higher surface tension in the aerosolized particles caused by the fluorescein salt. What Table 4 does show, though, is that except for the NOT, the Aeroneb consistently generated larger particles than the Collison and with a broader distribution (as measured by the geometric standard deviation [GSD]) in all the chambers tested. The Aeroneb also generated a higher humidity in each chamber tested except for the NOT, which would at least partly explain the differences in particle sizes seen. Even with the larger particle sizes obtained with the Aeroneb using fluorescein, between 70 and 80% of the particles measured had an MMAD of ≤5 μm. The only nebulizer-chamber combination to achieve less than 70% was the Collison in the NOT, where only 55.97% of particles were ≤5 μm. This larger particle size is likely a result of the higher humidification achieved in the NOT by the Collison.

TABLE 4.

Particle sizes generated using the Collison and Aeroneb to aerosolize fluorescein salt in different exposure chambersa

| Chamber | Nebulizer | MMAD (μm) | GSD (μm) | CMAD (μm) | % of particles of ≤3.5 μm | % of particles of ≤5 μm | AH (g/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHP | Collison | 3.05 | 3.67 | 0.67 | 60.00 | 84.06 | 1,018.05 |

| Aeroneb | 3.93 | 2.37 | 0.67 | 44.84 | 71.57 | 1,256.05 | |

| RWB | Collison | 2.96 | 2.84 | 0.65 | 64.07 | 89.11 | 822.88 |

| Aeroneb | 3.05 | 4.53 | 0.58 | 60.59 | 84.88 | 1,039.48 | |

| NOT | Collison | 5.05 | 1.54 | 0.63 | 27.47 | 55.97 | 1,360.18 |

| Aeroneb | 3.05 | 2.94 | 0.58 | 59.03 | 80.89 | 1,302.00 | |

| FWB | Collison | 2.21 | 3.41 | 0.63 | 70.34 | 86.55 | 677.36 |

| Aeroneb | 3.28 | 2.36 | 0.67 | 54.86 | 74.46 | 921.15 | |

Shown are the mass mean aerodynamic diameter (MMAD), geometric standard deviation (GSD), count median aerodynamic diameter (CMAD), percentages of particles less than or equal to 3.5 and 5 μm in size, and absolute humidity (AH) in the exposure chamber, in grams per cubic meter.

DISCUSSION

We report here our efforts to assess the Aeroneb as an alternative to the Collison nebulizer by comparing aerosol performances across various exposure chambers for both bacteria and viruses. Aerosolization of pathogens was also compared to simultaneous aerosolization of fluorescein salt to evaluate the impact of the different nebulizers on pathogen viability. A reduction in the SF of infectious agents compared to the SF of fluorescein salt was assumed to be due to a reduction in pathogen viability, but these results were not confirmed with live/dead staining or electron microscopy. SF and AE are easily calculated and do not require extra experiments separate from key experiments, allowing them to be used to assess aerosol performance between experiments. Fluorescein salt experiments should be performed separately from key experiments to ensure that the experimental design is not altered. The aerosol exposures performed were of 10-min durations and utilized airflow set to reach one complete air change in the exposure chamber every 2 min.

In agreement with what we have reported previously for F. tularensis and RVFV, the choice of exposure chamber impacts aerosol performance, with smaller chambers (by total volume) typically producing a better SF than a larger chamber for the Collison. The data that we report here also demonstrate that while the choice of nebulizer affects the SF, the impact is dependent upon the chamber used. In the NOT, the Aeroneb did not improve the SF compared to the Collison for either LVS or influenza virus. Yet in the RWB, FWB, and NHP HO chambers, the Aeroneb improved SF performance compared to the Collison for influenza virus and other viral pathogens but had a minimal impact on the SF for LVS. Particles generated by the Aeroneb were generally larger than those generated by the Collison, except in the NOT, but 70 to 80% of the particles generated by the Aeroneb were in the “respirable” range (MMAD of ≤5 μm) that would reach the deep lungs. Humidity levels were generally higher with the Aeroneb than with the Collison, except in the NOT, which may explain the differences seen in SFs and particle sizes with the Aeroneb in the other chambers.

The data presented here demonstrate that for viral pathogens, depending upon the chamber used, the superior aerosol performance of the Aeroneb over the Collison would make it easier to achieve desired challenge doses with less nebulizer material. To illustrate this, we show in Table 5 that to reach a target dose of 4.5 × 107 PFU of influenza virus in a macaque with a starting nebulizer concentration of 7.1 × 108 PFU/ml in an NHP HO chamber, it would take 121.19 min with the Collison versus 18.21 min with the Aeroneb. These theoretical results were confirmed during the development of an experimental model in macaques for aerosol exposure to H5N1 (21). The use of the Aeroneb makes certain experimental designs and targets more feasible, as it achieves higher doses with a smaller volume and less time, meaning that there will be less time for the animal to be anesthetized and a lower concentration in the nebulizer to achieve the desired dose. Particularly in circumstances where virus challenge doses must be quite high to achieve reproducible disease in the animal model, the use of the Aeroneb may make these studies more feasible and eliminate requirements to concentrate the agent through sucrose gradient purification or other means.

TABLE 5.

Theoretical aerosol duration to reach a target H5N1 dose using the Collison or the Aeroneb in an NHP HO chambera

| Parameter | Value for nebulizer |

|

|---|---|---|

| Collison | Aeroneb | |

| Target dose (PFU/ml) | 4.50E+07 | 4.50E+07 |

| Nebulizer concn (PFU/ml) | 7.10E+08 | 7.10E+08 |

| MVb (liters/min) | 0.4628 | 0.4628 |

| SF | 1.13E−06 | 7.52E−06 |

| Aerosol concn (PFU/ml) | 8.02E+05 | 5.34E+06 |

| Duration (min) | 121.19 | 18.21 |

To reach the same target dose with the same concentration of H5N1, the Collison would require a 121-min aerosol duration, while the Aeroneb would require only an 18-min aerosol duration.

MV, minute volume.

Previous studies have suggested that the Collison may damage pathogens during the process of aerosolization through mechanical and shear forces (14). Fluorescein salt was used in some experiments to act as a surrogate for microorganisms to determine the ideal SF of each aerosol generator given loss within the system. The small size and lack of a membrane ensure that the fluorescein salt will not be damaged by the aerosolization process, and thus, the loss of fluorescein salt during aerosolization can be attributed to leaks in the exposure system and adhesion of aerosol particles to equipment. Any additional decrease in the SF of pathogens compared to the SF of fluorescein following aerosolization is likely due to a loss of viability of the organism. The vegetative LVS bacteria had a significant drop in the SF relative to that of fluorescein salt (1 to 3 log10 units) in all the combinations of nebulizer and exposure chamber tested here. This was despite the relatively high RH generated by either nebulizer. Reflecting the apparent loss of bacterial viability, the AE was quite low for LVS using either nebulizer.

The influenza virus SF also dropped relative to that of fluorescein salt for the Collison in the FWB and NHP HO chambers but not in the NOT. In contrast, the SF for influenza virus aerosolized with the Aeroneb did not drop relative to that for fluorescein salt in any of the chambers tested. These data suggest that for viral pathogens, the superior SF of the Aeroneb over the Collison may be at least partially due to improved aerosol viability. Relative humidity did not appear to substantially alter the SF for influenza virus, although the RH was high for all the nebulizer-chamber combinations tested. Additional data generated with RVFV and the encephalitic alphaviruses further confirmed the superior SF performance of the Aeroneb with viral pathogens. It is important to note that these studies were conducted within highly controlled environments with great control over experimental conditions and are not reflective of agent behavior and viability in an aerosol generated in a natural environment.

The data presented in this paper indicate that the Aeroneb is a suitable alternative to the Collison for infectious disease aerobiology research, particularly for viral pathogens. These data have been successfully used in developing a macaque model for respiratory exposure to highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (21). The data presented here suggest that exploration of aerosol generators other than the Collison is recommended when developing new animal models for human respiratory infections. The studies reported here, combined with our recently reported data on tularemia aerosols with rabbits, also emphasize the importance of developing well-characterized challenge models. These models will be essential for testing and evaluation of new vaccines or therapeutics for protection against challenge. Future studies will evaluate other aerosol generators that generate particles of different sizes as well as alternative aerosol sampling devices, particle compositions, environmental parameters, and exposure chambers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal use.

Experiments described in this report that involved animals were approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s IACUC. Research was conducted in compliance with Animal Welfare Act regulations and other federal statutes relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adheres to the principles set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (22). The University of Pittsburgh is accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC).

Biosafety.

All aerosol experiments for this study were performed in a class III biological safety cabinet within a dedicated aerobiology suite inside a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) facility operated by the Center for Vaccine Research. For respiratory protection during H5N1, alphavirus, or RVFV experiments, personnel wore powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs) while performing plaque assays within class II biosafety cabinets under BSL3 conditions, using Vesphene IIse (diluted 1:128; Steris Corporation) for disinfection. Spatial and temporal separation was maintained between H5N1, RVFV, and all other infectious agents. Work with F. tularensis LVS and seasonal influenza virus was conducted under BSL2+ conditions in a class II biosafety cabinet, using 10% bleach or Vesphene IIse (1:128) for disinfection.

Bacteria.

A frozen stock of F. tularensis LVS, originally obtained from Jerry Nau and passaged a single time in culture, was used for aerosol experiments. Prior to aerosol exposure, LVS was grown on cysteine heart agar (CHA) (BD Difco and BD BBL; Becton, Dickinson, La Jolla, CA) for 2 days at 37°C with 5% CO2 and then overnight in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (BD BBL) supplemented with 2.5% ferric pyrophosphate and 1.0% l-cysteine hydrochloride as previously described (3). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in an orbital shaker at 200 rpm and harvested at between 15 and 18 h to ensure that the bacteria were in the logarithmic growth phase. The optical density (OD) of the culture was read, and the bacterial concentration was estimated based on previously determined OD-to-CFU ratios (3). The concentration of LVS was confirmed by colony counts on CHA.

Influenza virus.

Two H1N1 strains, A/PR/8/34, obtained from Rich Webby (University of Pittsburgh, PA), and A/Ca/04/09, from Biodefense and Emerging Infections Resources (Manassas, VA), were used in these experiments. An H3N2 virus (influenza A/Syd/5/37) obtained from Michael Murphy Corb (University of Pittsburgh, PA) and an H5N1 virus (A/Vietnam/1203/04) obtained from Daniel Perez (University of Georgia, GA) were also used. The H1N1 and H3N2 viruses were propagated in MDCK cells and frozen at −80°C until use. The H5N1 (A/Vietnam/1203/2004) stock was propagated in specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chicken eggs, and the stock was frozen at −80°C until use. Temporal and spatial separation of all strains of influenza virus was maintained throughout the experiments; H1N1 and H3N2 viruses were used under BSL2 conditions, while H5N1 was used under BSL3 conditions. Prior to aerosol experiments, influenza viral stocks were diluted in viral growth medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium [DMEM], 2.5% of 7.5% bovine serum albumin [BSA] fraction V, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% HEPES buffer, and 0.1% l-1-tosylamide-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone [TPCK]-trypsin).

Rift Valley fever virus.

The stock of RVFV (isolate ZH501) used in these experiments was derived from an infectious clone as previously described (23). Prior to aerosol experiments, the virus was thawed and diluted in DMEM containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS), glycerol, and antifoam A for aerosolization.

Alphaviruses.

Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) (isolate INH9813), Western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV) (isolate Fleming), and Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) (isolate V105) were derived from infectious clones of human isolates passaged a single time in BHK cells. Stocks were thawed and diluted in Opti-MEM for aerosolization.

TCID50 (50% tissue culture infective dose) assay.

Confluent MDCK cells (ATCC CCL-34) were infected with 10-fold serial dilutions of influenza virus samples in a 96-well plate. The plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48 h. Cells were then examined under a microscope for cytopathic effect (CPE) compared to the uninfected MDCK cell controls. Each well was scored as positive or negative for CPE. Viral titers were then calculated using the method described by Reed and Muench (25).

Plaque assay.

Virus samples were adsorbed onto confluent monolayers of Vero, Vero E6, or MDCK cells in duplicate wells of a 6-well plate for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. After incubation, the inoculum was removed, and cells were overlaid with a 1% nutrient overlay (2× modified Eagle medium, BSA, penicillin-streptomycin, 2% agarose). Plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for up to 5 days, depending on the virus. Cells were fixed with 37% formaldehyde, agar plugs were removed, and cells were stained with a 0.1% crystal violet stain to visualize plaques. Wells with 15 to 100 plaques were counted for titer calculations. H5N1 plaque assays were performed in the same manner as for seasonal influenza virus plaque assays, with the following changes: following the addition of the inoculum, the plates were incubated at 4°C for 10 min and then incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 50 min, and a 0.9% nutrient overlay was used instead of a 1.0% nutrient overlay.

Aerosol exposures.

The AeroMP or Aero 3G aerosol management system (Biaera Technologies, Hagerstown, MD) was used to control, monitor, and record aerosol parameters during aerosol experiments. Unless otherwise noted, the durations of aerosols were 10 min. The airflow parameters of the aerosol experiments were programmed based on chamber volume in accordance with protocols used to infect animals. Air input (primary and secondary air) and vacuum (exhaust and sampler) were set in balance at one-half of the chamber volume, to ensure one complete air change in the exposure chamber every 2 min. Aerosols were generated using either a three-jet Collison nebulizer or an Aeroneb nebulizer (Fig. 1). Airflow through the Collison was set at 7.5 liters per min and 26 to 30 lb/in2. The Aeroneb utilizes a vibrating mesh, not pressurized air, for generating aerosol particles. The Aeroneb was placed in line with the secondary/dilution air to push the air into the exposure chamber. Because exposure chamber structure and volume can influence aerosol performance (5), four exposure chambers were used for these experiments: the rodent nose-only tower (NOT), the rodent whole-body (RWB) chamber, the ferret whole-body (FWB) chamber, and the nonhuman primate head-only (NHP HO) chamber, with chamber volumes of 12 liters, 39 liters, 44 liters, and 32 liters, respectively. Table S1 in the supplemental material lists the aerosol parameter settings for exposure chambers and nebulizers.

Aerosol sampling.

Bioaerosol sampling was performed using an all-glass impinger (AGI) (Ace Glass, Vineland, NJ) calibrated with a Gilibrator calibrator to ensure an airflow of 6.0 ± 0.25 liters/min. The AGI is attached to the side of the aerosol exposure chamber in an area close to the breathing zone. For LVS aerosols, 10 ml of BHI broth and 40 μl of antifoam A (catalog number 10794; Fluka) were added to each AGI. For virus aerosols, 10 ml of cell culture medium and 80 μl of antifoam were added to each AGI. For RVFV aerosols, glycerol was also added. For VEEV, WEEV, and EEEV aerosols, 1% fetal calf serum (FCS) was also added to the culture medium. The aerosol concentration was determined as previously described (3, 5).

Aerosol performance.

Aerosol performances between nebulizers were compared using the SF and aerosol efficiency (AE). The SF was determined, as previously described (3, 5), as the ratio of the aerosol concentration (determined from the AGI) to the starting concentration in the aerosol generator. AE is the ratio of the aerosol concentration to the theoretical maximum aerosol concentration, as previously described (20). Aerosol particle size was measured by the mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) and geometric square deviation (GSD) using an aerodynamic particle sizer (APS) (model number 3321; TSI, Shoreview, MN).

Fluorescein.

Fluorescein salt (Sigma) was added in some aerosol experiments to be used as an indicator of the maximum SF given natural loss within the aerosol exposure system. Fluorescein salt was dissolved at a concentration of 0.1 mg in 1 ml of double-distilled water (ddH2O) prior to addition to nebulizer contents. Initial studies were conducted (data not shown) to verify that the addition of fluorescein did not alter pathogen viability or quantitation in culture, whether by plating on agar (F. tularensis) or by a TCID50/plaque assay (influenza virus).

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism 6 was used to create all figures and to perform two-sided Mann-Whitney U tests to compare the SFs and aerosol efficiencies between nebulizers. This nonparametric test was chosen due to the nonnormal distribution of results and the high frequency of outliers.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research described here was sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, grants R01 A102966-01A1 and R21 NS088326-01, and by Defense Threat Reduction Agency grant number W911QY-15-1-0019 and is sponsored by the Department of the Army, U.S. Army Contracting Command, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Natick Contracting Division, Ft. Detrick, MD. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the Government, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

We give special thanks to past and present members of the Hartman and Klimstra laboratories at the University of Pittsburgh, especially Stacey Barrick, Matthew Dunn, Christina Gardner, Theron Gilliland, Jr., Joe Albe, and Aaron Walters.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00747-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fernstrom A, Goldblatt M. 2013. Aerobiology and its role in the transmission of infectious diseases. J Pathog 2013:493960. doi: 10.1155/2013/493960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas R, Davies C, Nunez A, Hibbs S, Flick-Smith H, Eastaugh L, Smither S, Gates A, Oyston P, Atkins T, Eley S. 2010. Influence of particle size on the pathology and efficacy of vaccination in a murine model of inhalational anthrax. J Med Microbiol 59:1415–1427. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.024117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faith S, Smith LK, Swatland A, Reed DS. 2012. Growth conditions and environmental factors impact aerosolization but not virulence of Francisella tularensis infection in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:126. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saini D, Hopkins GW, Chen C, Seay SA, Click EM, Lee S, Hartings JM, Frothingham R. 2011. Sampling port for real-time analysis of bioaerosol in whole body exposure system for animal aerosol model development. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 63:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed DS, Bethel LM, Powell DS, Caroline AL, Hartman AL. 2014. Differences in aerosolization of Rift Valley fever virus resulting from choice of inhalation exposure chamber: implications for animal challenge studies. Pathog Dis 71:227–233. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox C, Goldberg L. 1972. Aerosol survival of Pasteurella tularensis and the influence of relative humidity. Appl Microbiol 23:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hood A. 1977. Virulence factors of Francisella tularensis. J Hyg (Lond) 79:47–60. doi: 10.1017/S0022172400052840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy C, Reed D, Hutt J. 2010. Aerobiology and inhalation exposure to biological select agents and toxins. Vet Pathol 47:779–789. doi: 10.1177/0300985810378650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lackemeyer MG, de Kok-Mercado F, Wada J, Bollinger L, Kindrachuk J, Wahl-Jensen V, Kuhn JH, Jahrling PB. 2014. ABSL-4 aerobiology biosafety and technology at the NIH/NIAID integrated research facility at Fort Detrick. Viruses 6:137–150. doi: 10.3390/v6010137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodlow RJ, Leonard FA. 1961. Viability and infectivity of microorganisms in experimental airborne infection. Bacteriol Rev 25:182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Malley KJ, Bowling JD, Barry EM, Hazlett KRO, Reed DS. 13 May 2019. Development, characterization and standardization of a nose-only inhalation exposure system for exposure of rabbits to small particle aerosols containing Francisella tularensis. Infect Immun doi: 10.1128/IAI.00198-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May K. 1973. The Collison nebulizer: description, performance and application. J Aerosol Sci 4:235–243. doi: 10.1016/0021-8502(73)90006-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy CJ, Pitt MLM. 2012. Infectious disease aerobiology: aerosol challenge methods, p 65–79. In Swearengen JR. (ed), Biodefense research methodology and animal models, 2nd ed CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhen H, Han T, Fennell DE, Mainelis G. 2014. A systematic comparison of four bioaerosol generators: affect on culturability and cell membrane integrity when aerosolizing Escherichia coli bacteria. J Aerosol Sci 70:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2014.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas RJ, Webber D, Hopkins R, Frost A, Laws T, Jayasekera PN, Atkins T. 2011. The cell membrane as a major site of damage during aerosolization of Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:920–925. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01116-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ari A, Atalay OT, Harwood R, Sheard MM, Aljamhan EA, Fink JB. 2010. Influence of nebulizer type, position, and bias flow on aerosol drug delivery in simulated pediatric and adult lung models during mechanical ventilation. Respir Care 55:845–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang G, David A, Wiedmann TS. 2007. Performance of the vibrating membrane aerosol generation device: Aeroneb micropump nebulizer. J Aerosol Med 20:408–416. doi: 10.1089/jam.2007.0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimmick R, Vogl W, Chatigny M. 1973. Potential for accidental microbial aerosol transmission in the biological laboratory. Biohazards Biol Res 1973:246–266. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stephen EL, Dominik JW, Moe JB, Spertzel RO, Walker JS. 1975. Treatment of influenza infection of mice by using rimantadine hydrochlorides by the aerosol and intraperitoneal routes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 8:154–158. doi: 10.1128/aac.8.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dabisch P, Yeager J, Kline J, Klinedinst K, Welsch A, Pitt ML. 2012. Comparison of the efficiency of sampling devices for aerosolized Burkholderia pseudomallei. Inhal Toxicol 24:247–254. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2012.666682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wonderlich ER, Swan ZD, Bissel SJ, Hartman AL, Carney JP, O’Malley KJ, Obadan AO, Santos J, Walker R, Sturgeon TJ, Frye LJ Jr, Maiello P, Scanga CA, Bowling JD, Bouwer AL, Duangkhae PA, Wiley CA, Flynn JL, Wang J, Cole KS, Perez DR, Reed DS, Barratt-Boyes SM. 2017. Widespread virus replication in alveoli drives acute respiratory distress syndrome in aerosolized H5N1 influenza infection of macaques. J Immunol 198:1616–1626. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Research Council. 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bales JM, Powell DS, Bethel LM, Reed DS, Hartman AL. 2012. Choice of inbred rat strain impacts lethality and disease course after respiratory infection with Rift Valley fever virus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:105. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Research Council Committee on Animal Models for Testing Interventions Against Aerosolized Bioterrorism Agents. 2006. Overcoming challenges to develop countermeasures against aerosolized bioterrorism agents: appropriate use of animal models. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Epidemiol 27:493–497. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.