Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

While resistance training (RT) can lead to acute improvements in psychological, physiological and psychosocial outcomes, prevalence rates remain low in college-age females likely due to perceived barriers. This study compared the effects of an acute bout of both a functional (FRT) and traditional resistance training (TRT) session on affect, state anxiety enjoyment and physiological measures.

METHODS:

Females (n=34, mean age = 27±4.5 years) not currently meeting ACSM RT guidelines completed 4 sessions (2 FRT, 2 TRT) within 4-weeks in a randomized crossover design. Session 1 familiarized participants to the RT exercises. Session 2 consisted of 2×10 moderate intensity repetitions. Outcome measures included affect and state anxiety (pre, post, and 15-minutes post-exercise); enjoyment (post), and manipulation measures were RPE and heart rate HR).

RESULTS:

Between condition comparisons indicate change scores in state anxiety pre- to post-15 (p=0.028) and enjoyment levels post- (p=0.02) were significantly greater in FRT than TRT. Within condition analyses revealed pre- to post-15 changes in affect were positive and greater in FRT (d=0.79) than TRT (d=0.53, p=0.47), and greater in decreases in state anxiety (FRT, d=−0.58; TRT, d=−0.37, p=0.028). Mean session RPE was not significantly different between conditions (FRT 6±1.2 units; TRT 6.3±1.1 units; p=0.11), though average % of age predicted max HR (FRT 68.7±7.6; TRT 57.1±8.4) was significantly different (p<0.01).

CONCLUSION:

Findings suggest that compared to TRT, FRT is associated with higher acute positive psychological states, higher levels of enjoyment and greater energy expenditure. Future studies are recommended to examine additional measures of affect and in-task time points to determine how these responses relate to maintenance and adherence, thereby potentially increasing the proportion of college-females meeting ACSM RT and MVPA guidelines.

Keywords: Exercise, Strength, Physical Activity, Feelings

Introduction

College-age women represent a population with low moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and resistance training (RT) levels. College-age women have been shown to be less physically active than their male counterparts (1). The 2015 American College Health Assessment (ACHA) survey found that 50% of college males and 43% of college females self-reported achieving American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines for MVPA; while 45% of males and only 33% of females achieved the RT guidelines (2). While national surveys assessing physical activity (PA) levels may obtain objective data through accelerometry, measurement of RT relies solely on self-report, thus RT prevalence may be even lower than reported. While activity prevalence rates are low for college-age women, rates of psychological distress, such as anxiety, stress, depression and dissatisfaction about their physical appearance are high (2). Engaging in regular RT by young women provides physical, physiological and psychological health benefits, while providing additional bone health benefits (3). If a mode of RT could be found that addressed the typical barriers to RT experienced by college-aged females it could increase prevalence rates of activity and lower psychological distress.

Self-reported barriers to exercise include lack of motivation, disliking the exercise, disliking exercising in public, lack of knowledge on exercise and embarrassment (4,5). Barriers to RT reported by women include that it involves too much work, it is too tiring to perform, it makes them look silly while exercising, it causes muscle soreness and women fear looking masculine (6,7). It is important to understand the characteristics of RT that may address the aforementioned barriers, which may be associated with low RT prevalence in this population despite the many benefits of performing RT. In an effort to better understand reasons individuals may enjoy, adhere to or dropout from regular exercise, researchers have begun to examine acute affective and psychosocial responses to single bouts of exercise (8).

Affective responses experienced during and after exercise are important to consider in acute bouts of exercise. Acute bouts of RT have shown psychological improvements such as increased pleasure, (9,10), positive affect (11) and state anxiety (12), which may translate to long-term benefits with sustained repetition over time (13). To date, affective valance has been measured using a variety of scales to assess different dimensions of affect. One measure commonly assessed in aerobic exercise and RT is feelings of pleasure/displeasure (via Feelings scale) (14), which relates to a simple primitive feeling one may experience surrounding exercise. Feelings of pleasure/displeasure are one dimension of core affect, or the circumplex model (10,15), and may influence exercise enjoyment and the likelihood of repeating that exercise in the future (16,17). Examinations of the relationship between affect, enjoyment and state anxiety as a result of exercise have shown that any negative experience during and after one bout of exercise may increase the chances of attrition, especially in exercise novices undertaking RT (18). Mechanistic responses for changes in affect as a result of an acute bout of exercise have included the environment (e.g., exercise setting), characteristics of the exercise (e.g., intensity and type), and individual differences (e.g., exercise history, demographics) (11). Intensity of exercise has received much attention in the context of exercise, and the Dual Mode Theory (19) suggests that low –moderate intensity exercise elicits a more positive affect response, while high intensity elicits a more negative affective response. The model suggests that exercise above ventilatory threshold causes increases in ventilation, blood lactate and respiration, thus causing interceptive cues to dominate over cognitive processes and elicit feelings of unpleasantness.

The effects of acute RT sessions on affective response and enjoyment have yielded promising but inconsistent conclusions on the outcome measures (such as affect, energy, state anxiety, tiredness, calmness and tension). Single bouts of RT sessions have led to improvements in positive and negative affect (20) and reductions in state anxiety (20–22), while other studies have shown conflicting results suggesting either no significant changes (23) or increases in state anxiety (21,22). Generalizability of results of these prior studies is limited and attributed to characteristics of highly selected samples. Specifically, the majority of college students studied in acute RT sessions were previously aerobically trained (20), currently engaged in RT programs (24) or already enrolled in weightlifting classes (25). Investigations of acute RT sessions in college students have shown negative associations between enjoyment levels and RT intensity (8,26). Evidence has shown a high positive correlation between enjoyment and affective response, and manipulations of exercise intensity have shown that light to moderate intensity RT, or 50–70% 1 repetition max (RM), resulted in the greatest improvements in psychological states (8,25), as explained by the Dual-mode theory.

Most research examining affective responses and enjoyment of acute sessions has studied only one type (traditional) that primarily utilized machine-based exercises (8,24,25). Although RT has greatly increased in popularity, other types of training aside from traditional RT (TRT) have yet to be examined. One such type of training, “functional fitness”, is defined by the ACSM as the use of strength training to improve balance and ease of living, and was in the top 10 fitness trends in 2018 (27). The ACSM defines functional resistance training (FRT) as activities involving multiple muscle, joint and planar activities that are closely related to activities of daily living, combining upper and lower body movements to utilize more of the body in each movement (28). Few studies have examined FRT, though initial results suggest that FRT is associated with higher caloric expenditure (29) and similar muscular strength, endurance and gains in flexibility (30) compared to a TRT program. What has yet to be examined is the comparison of two types of RT sessions, while holding intensity constant to elicit the most favorable affective responses, as supported by the Dual-mode theory. FRT may be more feasible and accessible due to the minimal equipment needed and the flexibility to be performed in and out of a typical gym setting. FRT may also be more salient to a female population who has expressed barriers of disliking the exercise, disliking exercising in public, embarrassment (4,5) and fear of looking silly and masculine while exercising (6,7). A type of exercise addressing these barriers may lead to more positive feelings and enjoyment following acute bouts of exercise sessions.

While intensity manipulations of the RT program have been previously examined, there have been no studies of the effects of a different type of RT program, such as FRT, on affect and psychosocial measures (e.g. enjoyment) in a sedentary population with low PA levels and high psychological stress. The aim of this study was to compare acute bouts of a moderate intensity functional versus a traditional machine-based RT session on pre- to post- outcome measures of affect (pleasure/displeasure), state anxiety and enjoyment in college-age females who were novices to resistance training. This study assessed immediate and 15-minute post-exercise effects of state anxiety and affect following bouts of exercise. Evidence shows acute bouts of RT may cause a negative response to affect and state anxiety within session, followed by an increase in positive effects following exercise cessation (20). While previous research has assessed both in-task and post-exercise measures of affect, this study focused solely on one’s feelings following completion of a session. It was hypothesized that while state anxiety would be reduced and positive affect (pleasure) would increase after both conditions, the effect of FRT would be superior to those experienced in TRT. It was also hypothesized that participants would experience higher levels of exercise enjoyment following the FRT condition than TRT.

Methods

Design.

A randomized crossover experimental design was used. Participants completed a familiarization session followed by a testing session for one type of training, then the same format for the other type. Each participant completed 2 sessions (familiarization and testing) in a randomly assigned order of 2 conditions (FRT and TRT) for a total of 4 sessions. Data collected during the testing session included assessments of affect and SA pre-, post-0 and post-15 (minutes), and enjoyment immediately post-exercise. Heart rate (beats per minute) and RPE (0–10 scale) were monitored by trained research assistants throughout each of the testing sessions. A power analysis based on a medium effect size (d=0.50) between repeated measures for affective response between condition (FRT vs TRT) and time (pre-, post- and 15-minutes post-exercise) yielded a sample size of 34 participants required to detect statistically meaningful changes (α level 0.05) with statistical power of 0.80(31).

Participants.

Upon receiving Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, college women were recruited from a large urban university campus in Boston, MA. Participants were recruited using flyers posted around campus and listserv email blasts. Recruitment materials were designed to target novice females not currently meeting RT guidelines (2x/week) and were interested in learning more about resistance training. Specific inclusion criterion were: 1) age 18–35 years old; 2) current enrollment in a college or University as an undergraduate/graduate student; 3) Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) (32) medical clearance; 4) not meeting ACSM RT (<2 days of muscle-strengthening exercises per week); and 5) body mass index (BMI) of 18.5–40 kg/m2. Participants who were interested contacted the study team and were screened via telephone to determine eligibility. The telephone screen included an administration of the PAR-Q (32), and any “yes” response(s) required a healthcare provider’s clearance in order to participate in the study. Eligible participants were scheduled for an in-person baseline session.

Procedures

After an initial phone screening, participants were invited to come to the laboratory on 5 different occasions. At the baseline session, participants were given more information on the study, read and signed the informed consent, completed a demographic questionnaire and had their height and weight objectively measured using standard procedures. BMI was calculated using the average of the two measured heights and weights. The PI then randomly assigned participants to an exercise sequence (TRT then FRT or FRT then TRT sequence) using a table of random numbers and scheduled their 4 RT sessions. Each participant chose a preferred time of day and attended 4 sessions at the same time of day, with each visit separated by 2–7 days to allow for adequate recovery and time for delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) to subside (20,24). Participants were asked to refrain from performing exertional exercise 24 hours prior to each session. Participants were taken through each session one-on-one with the same exercise trainer who was blinded to the study hypotheses. Duration of session and exercise volume were held constant between both conditions. Repetition-volume was calculated by using the total number of repetitions performed within the workout. Sessions lasted 32 minutes on average, and both conditions contained a total of 160 repetitions outside of warm-up sets. FRT movements were chosen for novice strength trainers based on the 7 primary movements patterns identified in the literature (33). TRT movements were machine-based, targeting upper and lower body major muscle groups. See Table 1 for a description of exercises in each type of RT.

Table 1.

List of exercises in the functional and traditional resistance training session. All exercises were performed in 10 repetitions for a total of 160 repetitions for both types of RT.

| Exercise Order |

Traditional RT (Machine- based) |

Functional RT (Free weight-based) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chest Press | Modified (box) Push-up |

| 2 | Horizontal Leg Press | Dumbbell Goblet Squat |

| 3 | Seated Row | Dumbbell Split-Stance 1-Arm Row* |

| 4 | Prone Leg Curl | Dumbbell 2-leg Romanian Deadlift |

| 5 | Seated Shoulder Press | Dumbbell Walking Lunge + Rotation** |

| 6 | Leg Extension | Dumbbell Wood Chop** |

| 7 | Cable Tricep Pushdown | Dumbbell Step-up** |

| 8 | Cable Bicep Curl | N/A |

Programmed at 10 repetitions per side.

Programmed at 5 repetitions per side.

Sessions 2 and 4.

Sessions 2 and 4 consisted of familiarizing participants to the exercises and assessing a 10RM for FRT and for TRT exercises. Each session began with standardized instructions on how to use the RPE scale(34), followed by a 5-minute warm-up on an Arc Trainer machine (Model #630A, Owatonna, MN) involving both the upper and lower body. Starting weights were pre-determined from a range of weights previously assessed in the familiarization session by the Research Assistant. Research assistants received extensive training on exercise testing sessions and worked with the same participant for each session. Muscular strength was assessed using a 10RM test which is consistent with previous protocols used in beginners due to the safety and higher validity this tests yields in novices compared to the 1RM test (35). Rest time between sets was consistently set at 1:30–2 minutes to ensure full recovery. A typical entire session lasted approximately 40–45 minutes. Due to the nature of FRT movements, both FRT and TRT intensities (load) were set using RPE scores assessed during the 10RM familiarization session in lieu of using percentages. Starting weights for testing session were set within an RPE range of 5–7 on the modified BORG RPE scale (36), which corresponds to 50–70% 10RM, otherwise known as a moderate intensity or effort (35). Warm-up sets were set at a 3–4 RPE range, followed by two sets of 10 repetitions set at a 5–7 RPE range, with research assistants assessing RPE and ensuring participants could successfully and safely complete their last repetition of each set. They then increased or decreased weight to maintain an RPE of 6–7 and completion with good form, which has been previously used in studies examining FRT (30) and aligns with common intensity prescriptions for beginners (35).

Sessions 3 and 5.

Sessions 3 and 5 consisted of collecting data pre- and post- exercise assessments for FRT and TRT. Upon arrival, participants placed the Polar H7 HR monitor on, sat quietly for 5-minutes, completed the Feeling Scale (FS) and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (SAI) and were reminded of the RPE scale. Following a 5-minute warm-up, exercises were completed in the same order as the familiarization session. An initial warm-up set of 3–5 repetitions was performed, followed by 2 sets of 10 repetitions. Rest time between warm-up sets and the initial set of 10 lasted for 30 seconds, while 60 seconds of rest was given between each set of 10 and exercise transitions. RPE was monitored and recorded at the conclusion of each set, and if an exercise set was rated outside of the 5–7 range, the weight was increased or decreased by 5–10% to elicit a 5–7 rating (30). Upon completion of all exercises within the session, FS, SAI and Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) were immediately completed in a quiet office area, where they remained until completing the FS and SAI 15-minutes post-exercise completion. During each session, participants were allowed to drink water ad libitum, but were held to constant rest times as monitored by research assistants and the primary investigator. Participants were allowed to withdraw at any point during the session.

Measures

Outcome Measures

Affect and Anxiety.

The Feeling Scale (14) (FS) is a single-item 11-point scale that assesses affective valance and measured participants immediate pleasure/displeasure ratings on a scale of −5 (dislike) to +5 (like). The FS has commonly been used to assess affect during exercise (8–10,37). State anxiety was measured using the 20-item Form Y-1 (SAI) of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (38). Participants responded to each item on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much so), with higher scores indicating higher state anxiety. Ten of the question stems were reverse-coded. Cronbach’s α for SAI during and after an acute bout of RT has most recently been reported as ranging from 0.75 to 0.92 across different intensities and time points(8). For the current study, Cronbach’s α 0.94. Composite scores for SAI were calculated by summing the items.

Enjoyment.

The Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) (39) assessed enjoyment following both sessions. The PACES contains 18 bipolar statements that anchor the ends of a 7-point response scale where participants choose the number that most closely corresponds to the way they feel at the moment about the physical activity they have just completed [for example, “I enjoy it (1)...I hate it (7)”; “I dislike it (1) … I like it (7)”]. Composite scores were calculated for the PACES scale by summing the items. PACES has been found to be reliable (internal consistency α =.93) and valid(39). For the current study, Cronbach’s α was 0.94.

Fidelity Check Measures

Intensity.

Participants wore a Polar H7 monitor and chest strap to monitor HR for 5-minutes before the start of each exercise condition (FRT and TRT), and continued through completion of the final exercise using the Polar Beat app. Heart rate measures assessed were the 5-minute resting HR, the average HR within sessions, and the change from resting to peak HR. Intensity was measured using the Ratings of Perceived Exertion (34); a 10-point scale with numerical ratings from 1 to 10, with verbal anchors of 1 = “rest,” 2 = “easy,” 3 = “moderate,” 4 = “somewhat hard,” 5 = “hard,” 7 = “very hard,” and 10 = “maximal.”. This scale has been validated for quantifying intensity in resistance training studies (36) and was used in lieu of percentage 1RM due to the nature of the FRT program (body weight and free weight movements).

Data analysis.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (SPSS 22.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Exploratory data analysis (EDA) was used to verify that composite scores for all outcome measures were normally distributed and whether data transformations were warranted. EDA was also used to detect any implausible values. Nonparametric procedures using ranks were used to account for the small sample size. Sensitivity analysis using parametric methods revealed qualitatively similar results. Affective response and SA composite scores were analyzed as continuous measures using a 2 (condition: functional and traditional RT) x 3 (time: pre-exercise, post-0 exercise and post-15-minute exercise) repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA). RM-ANOVA used the Greenhouse Geyser correction to protect against violations of Mauchly’s sphericity assumption. Post-hoc contrasts were conducted using linear regression and pairwise comparisons, accounting for multiplicity to avoid type I error, the probability of false positive results. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were also calculated by taking the mean difference and dividing by the pooled standard deviation. Effect sizes of 0.20 were considered to be small changes between means, while 0.50 to 0.80 were interpreted as moderate to large, respectively. Enjoyment, average session HR, % APMHR and average session RPE were analyzed using paired-sample t-tests. All statistical tests were two-sided and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the study sample. The sample included 34 participants, mean ± SD age of 27.3 ± 4.5 and a mean ± SD BMI of 25.2 ± 5.6. Using a 7-day physical activity recall administered in the NCHA-ACHA (2), it was found that participants met moderate PA guidelines on 2.62 ± 1.92 days/week, vigorous PA guidelines on 1.2 ± 1.8 days/week and resistance training guidelines on 0.9±0.3 days/week.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of study participants (N=34).

| Variable | Mean ± SD or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 27.3 ± 4.5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.2 ± 5.6 |

| Race | |

| Asian | 5 (14.7%) |

| Black or African American | 4 (11.8%) |

| White | 24 (70.6%) |

| Unknown/Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.9%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latina | 6 (17.7%) |

| Not Hispanic/Latina | 26 (76.5%) |

| Unknown/Prefer not to answer | 2 (5.9%) |

| Year in School | |

| First | 1 (2.9%) |

| Second | 5 (14.7%) |

| Third | 5 (14.7%) |

| Fourth | 4 (11.8%) |

| Graduate | 19 (55.9%) |

| Days Moderate PA/Week | 2.6 ± 1.9 |

| Days Vigorous PA/Week | 1.2 ± 1.8 |

| Days Resistance Training/Week | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

Affective Response (the Feelings Scale)

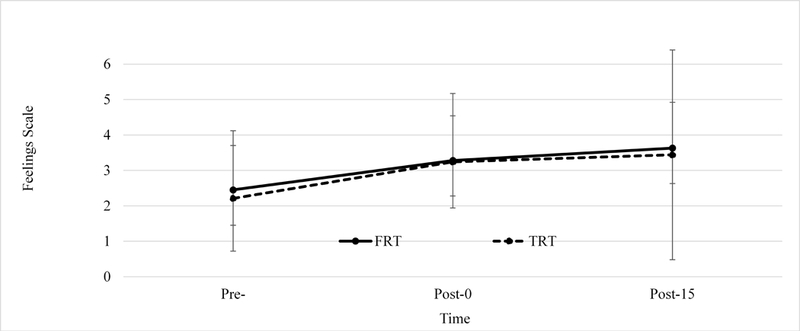

There were no significant differences in baseline affect values between FRT (2.5±1.7) and TRT (2.2±1.5, p=0.30). RM-ANOVA used the Greenhouse Geyser correction revealed a statistically significant difference over time in Feelings Scale main effects, F(2,66)=28.85, p<0.001. The condition x time interaction term did not attain statistical significance, F(2, 66)=0.103; p=0.753. Table 3 shows there were no significant differences between types of training (conditions) (see Table 3), however, Figure 1, pre- to post-15 changes in affect were greater in FRT (d=0.79) compared to TRT (d=0.53). Table 4 shows post-hoc pairwise tests indicating that affect increased significantly from pre- to post-0 and pre- to 15-minutes post-exercise for both conditions (all p<0.05).

Table 3.

Between-condition differences in affective response and state-anxiety (M±SD) change scores pre-, post-0 and post-15, enjoyment, HR and RPE post-0 FRT and TRT.

| Functional | Traditional | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-value |

| Change in Affect1 | |||||

| Pre to Post-0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.897 |

| Post-0 to Post-15 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.545 |

| Pre to Post-15 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.464 |

| Change in State Anxiety2 | |||||

| Pre to Post-0 | −5.7 | 7.4 | −3.2 | 7.8 | 0.084 |

| Post-0 to Post-15 | −1.9 | 4.3 | −0.7 | 4.2 | 0.261 |

| Pre to Post-15 | −7.7 | 8.5 | −3.9 | 7.0 | 0.028* |

| Enjoyment | 105.2 | 14.9 | 101.3 | 16.7 | 0.042* |

| RPE | 6.0 | 1.2 | 6.3 | 1.1 | 0.08 |

| Average Session HR | 132.4 | 15.5 | 110.2 | 17.1 | <0.001* |

| Change RHR to PHR | 96.2 | 19.8 | 70.5 | 21.0 | <0.001* |

| % APMHR | 68.7 | 7.6 | 57.1 | 8.4 | <0.001* |

Affective response measured via the Feelings Scale.

State anxiety measured via State Anxiety Inventory.

P<0.05 using paired t-tests.

Note: Change scores were calculated by subtracting post-0 and post-15 minute scores from pre-testing scores. P-values generated using log-transformed variables.

Figure 1.

There were no statistically significant differences between FRT and TRT sessions at baseline. There was a significant increase in affective response from pre- to post- (p<0.01) and pre- to 15-minutes post (p<0.01) the FRT session, and significant increase pre to post- (p<0.01) and pre- to 15-minutes post- (p<0.01) the TRT session.

Table 4.

Within-condition differences in affective response and state anxiety (M±SD) pre-, post-0 and post-15 FRT and TRT.

| Functional Resistance Training | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Measure |

Time | Mean | SD | p-value | p-value (pre to post-15 |

Effect Size d |

Effect size d (pre- to post-15) |

| Affect | Pre | 2.45 | 1.67 | ||||

| Post-0 | 3.28 | 1.89 | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.47 | 0.79 | |

| Post-15 | 3.63 | 1.29 | 0.403 | 0.22 | |||

| State Anxiety2 | Pre | 36.57 | 11.37 | ||||

| Post-0 | 31.57 | 10.03 | <0.001* | <0.001* | −0.47 | −0.58 | |

| Post-15 | 29.86 | 11.66 | 0.025* | −0.16 | |||

| Traditional Resistance Training | |||||||

| Outcome Measure |

Time | Mean | SD | p-value | p-value (pre to post15) |

Effect Size |

Effect size d (pre- to post-15) |

| Affect1 | Pre | 2.21 | 1.49 | ||||

| Post-0 | 3.24 | 1.30 | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.74 | 0.53 | |

| Post-15 | 3.44 | 2.96 | 0.336 | 0.09 | |||

| State Anxiety2 | Pre | 34.88 | 11.24 | ||||

| Post-0 | 31.71 | 9.54 | 0.024* | <0.001* | −0.30 | −0.37 | |

| Post-15 | 30.97 | 9.85 | 0.257 | −0.08 | |||

Affective response measured via the Feelings Scale.

State anxiety measured via State Anxiety Inventory.

P<0.05 using paired t-tests.

Note: P-values generated using log-transformed outcome measures.

State Anxiety Inventory

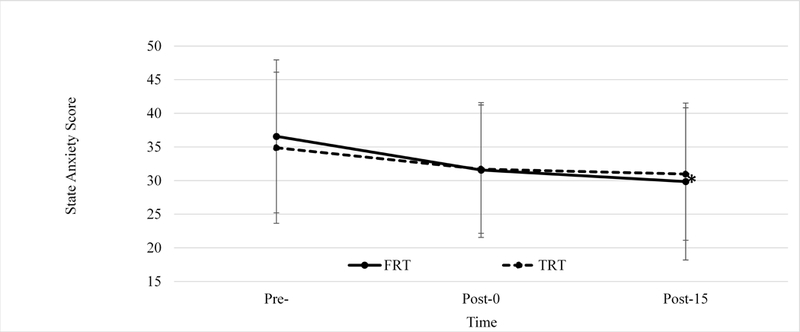

There were no significant differences in state anxiety baseline values between FRT (36.3±11.4) and TRT (34.9±11.2; p=035). There was a significant main effect of time F(1.34, 44.2)=21.62, p=0.001 and condition x time interaction F(1.64, 54.22)=76.48; p=0.036. Between condition comparisons revealed that decreases in SAI from pre- to post-15 in the FRT condition (−7.7±8.5; ES = −0.58) were significantly greater than the TRT condition (−3.9±7.0; p=0.028, ES = −0.37) (see Fig. 2 and Table 3). Post-hoc pairwise tests indicated that state anxiety significantly decreased from pre- to post-0 and from pre- to post-15 in both types of training (all p’s<0.05), though state anxiety also decreased post-0 to post-15 in the FRT condition (p=0.028) (see Table 4).

Figure 2.

There were no statistically significant differences between FRT and TRT sessions at baseline. State anxiety significantly decreased pre- to 15-minutes post- FRT (p=0.028) as compared to TRT. There was a significant decrease in state anxiety from pre- to post- (p<0.01) post- to 15-minutes post- (p=0.03) and pre- to 15-minutes post (p<0.01) the FRT session, and significant decrease pre to post- (p<0.02) and pre- to 15-minutes post- (p<0.01) the TRT session.

Enjoyment and Fidelity Checks (HR and RPE)

Paired t-tests revealed that enjoyment was significantly greater following the FRT (105.2±14.9) session as compared to the TRT (101.3±16.7) session; (p=0.023) (see Table 3). The HR and RPE responses to both conditions are shown in table 3. Mean session RPE was not statistically different between conditions, while all HR measures, including mean session HR, average % of APMHR and change from resting to peak HR were significantly greater in FRT as compared to TRT (all p<0.01). Spearman’s rank order correlations between RPE and changes in FS, SAI and post-session enjoyment in FRT or TRT were not significant (all p>0.05). Additionally, the mean session HR and changes in FS, SA and post-session enjoyment did not attain statistical significance in both FRT and TRT (all p>0.05).

Discussion

The novel findings of the current study were that acute bouts of FRT led to greater decreases in state anxiety and greater post-session enjoyment levels compared to TRT. Additionally, FRT led to a higher percentage of age-predicted max heart rate than TRT, while showing no differences in RPE. Both conditions led to greater improvements in affect and decreases in state anxiety from pre- to post-, suggesting acute positive effects of acute RT sessions on psychological health in this young female population. This is the first study to assess affect and state anxiety following two types of RT in participants who were not currently participating in RT while simultaneously controlling for intensity levels in both conditions. There have been several investigations regarding how acute bouts of RT may affect state anxiety and affect, although none have compared types of RT while controlling for the effects of intensity. Our study showed that moderate intensity FRT led to more favorable responses post-exercise. Though unstudied, future adherence may be supported by evidence of higher intensities being associated with less favorable responses and increases in non-adherence and dropout (10).

We hypothesized that participants would experience greater enjoyment following the FRT session, which is supported by the results. Enjoyment has been identified as a critical factor in exercise adoption and maintenance; thus, maximizing enjoyment in an RT session may lead to higher rates of adoption and maintenance. Exercise enjoyment has been positively correlated with the positive feelings and pleasure one experiences during exercise sessions (40). Taken together these observations from prior research may help to explain the findings of decreased state anxiety and increased enjoyment following FRT. Thus, maximizing enjoyment in an RT session may lead to higher rates of adoption and maintenance.

While previous research has focused on understanding the relationship between intensity and enjoyment (10), the present study held a moderate intensity in both conditions. This allowed for comparison of RT training modalities on factors that may address barriers to RT, which may be associated with low prevalence in this population. Investigations into the intensity-enjoyment relationship have revealed that enjoyment levels were increased following a moderate intensity TRT session as compared to a low and high intensity group (8). One RT intervention found greater increases in enjoyment and lower dropout rates in a moderate-intensity TRT program as compared to both a high-intensity FRT and aerobic training program, though greater intentions to continue in the high-intensity group (26). An optimal intensity has been identified to stimulate feelings of accomplishment, though exceeding that threshold may promote negative responses in affect and anxiety, as described by the dual-mode theory (8). Our results suggest that in novice RT individuals, acute sessions of moderate intensity functional movements led to decreases in state anxiety and increases in enjoyment as compared to machine-based movements. In long- term training, individuals may experience physiological and psychological increases (35), possibly causing initial starting weights to be perceived as easier. Weiss et al. increased weekly resistance (5% for upper body and 10% for lower body) while maintaining a 6–7 RPE over 7 weeks (30). A supervised gradual progression with participant feedback may be enhance long-term RT benefits, while monitoring enjoyment to decrease the likelihood of dropout.

While both types of training led to decreases in state anxiety pre- post- and pre- to 15-minutes post-, we also found significant decreases post- to 15-minutes post FRT, which is consistent with previous findings (8). No significant differences were found in the Feelings Scale between conditions, though both led to significant increases pre- to post- and post-15, with a positive trajectory occurring post- to post-15. While affect was not assessed within session, our findings of increased affect immediately post FRT and TRT support and favor the “maintenance” model typically seen at moderate intensities (41). Affect has been described as dynamic process that may continually change in response to an external stimulus, thus our collection of one measure of affect only pre- to post- did not allow us to capture within session changes in affect, which may have differed between or within conditions. Thus it is possible affect changed within session and rebounded post-session, though typically this rebound is seen in high-intensity exercise (41). The measurement of affect also needs to be taken into context. Though the Feelings Scale has been previously validated, it is a single-item scale measuring a psychological construct that may have an unacceptable low reliability. Most studies examining affective response to RT have largely relied on the Feelings Scale, though approaches measuring an additional aspect of core affect, perceived activation, has been introduced more recently in RT research. Previous approaches to measuring affective response and subsequent results have varied, but this study is limited to assessment of only one measure and post-assessment of affect, thus results must be interpreted accordingly.

Assessments of HR and RPE were conducted within sessions to maintain and control for moderate intensity. A surprising finding from the study revealed significant differences between types of RT for both average session HR and change from resting to peak HR during sessions, though no significant differences in RPE (FRT 6.0±1.2, TRT 6.1±1.1). The FRT session resulted in a significantly higher % of age-predicted maximum heart rate (APMHR) than that of the TRT session (68.7 ± 7.6% and 57.1 ± 8.4% APMHR, respectively). FRT may potentially contribute to one’s accumulation of MVPA exercise and also energy expenditure greater than that of TRT in a given day. Previous research has suggested that HR should not be used to quantify cardiorespiratory intensity during RT, since upper body exercises may restrict venous return and reduce stroke volume, causing an increase in HR to maintain cardiac output independent of increases in oxygen uptake. However, in the present study both TRT and FRT involved the use of similar muscle groups with the same exercise volume and intensity, thus it may be possible to make relative comparisons between these 2 types of RT using HR measurements. While average RPEs were similar between sessions, the range of RPEs across conditions (4.8 vs. 7.2) does represent differing levels of intensity,

Important implications of this study are that a unique type of training, FRT, may lead to moderate intensity activity, may be more transferrable to performing activities of daily life though future research on this transference is warranted. FRT may also address some of the commonly perceived barriers to RT experienced by women. Increases in perceptions of strength in females enrolled in RT interventions have been positively associated with increases in body image and intentions to continue RT (42), which may warrant future research on perceptions of strength between FRT and TRT interventions. Additionally, negative feelings associated with exercise may lead individuals to avoid or discontinue exercise (25), thus FRT is a promising type of RT that lends itself to further examinations of feasibility and enjoyment in longer-term interventions. Though the mechanisms by which FRT can elicit more positive psychological responses and greater enjoyment to exercise remain to be clarified, increasing pleasure and enjoyment could lead to greater adherence and maintenance to RT.

There are several limitations to this study. First, participants had a trainer randomly assigned to them for exercise sessions, while the lead author collected all surveys and data. This process may likely have led to artificial differences in sessions, although all trainers received the same training protocol, and were blinded to the scientific hypotheses of the study. Trainers were also rated on knowledge, delivery motivation and overall session satisfaction by participants at the end of the sessions, and results revealed no significant differences between trainers or within trainers (between conditions). Secondly, while the FRT exercises were chosen to meet the 7 primary movements previously identified in the literature (33), these exercises are not the only functional training movements, and varying the exercise selection potentially elicits varying inter-individual heterogeneity of responses among participants. FRT exercises in this study were multi-joint non-machine-based exercises similar to daily activities of life, thus there are a plethora of additional exercises that may be considered “functional” based on this definition. Thirdly, we maintained a moderate RPE rating of 5–7, future research is needed to examine the effectiveness of an RT program at these intensities on physiological and strength-related outcomes in conjunction with affective responses and enjoyment. Fourthly, there are other possible physiological and hormonal mechanisms unknown which were not measured in this study that may influence affective responses. Suggested mechanisms include changes in lactate concentration and peripheral fatigue, the hypothalamic adrenal pituitary-axis and autonomic nervous system and phase of a woman’s menstrual cycle (20). The influence of these unknown factors potentially bias our findings towards the null. Further research may extend the insights from the current study and include other physiological measurements, such as blood lactate, peripheral fatigue and oxygen uptake measurements, to investigate their effect on acute outcomes as operationalized in the present study. Lastly, to reduce participant burden, we only collected one dimension of affect (the Feelings Scale) in addition to state anxiety pre- post- affective response rather than in-task measures. Future studies will benefit from using a dimensional approach of the circumplex model and in-task assessments of affect, which would also allow for assessment of responses to individual exercises. While previous research has shown positive relationships between in-task and post-session affective response to RT (8), it is possible that within-session responses may translate to future adoption and maintenance differently than those experienced post-session.

Conclusion

In summary, both FRT and TRT contributed to decreases in state anxiety and increases in affective responses immediately after and 15-minutes after one acute session, though FRT led to significantly greater decreases in state anxiety compared to TRT. Greater enjoyment levels following FRT sessions may be indicative of future exercise adoption and maintenance in this type of training, as evidenced by previous findings (16). FRT led to a higher percentage of age-predicted max heart rate than TRT, while showing no differences in RPE. These results suggest that FRT may lead to greater decreases in state anxiety pre- to post-session, be more enjoyable and contribute to greater energy expenditure than TRT in female college students. This study provides preliminary evidence that FRT may have fewer barriers and greater positive outcomes than TRT while potentially being conducted at a higher intensity level. These findings, if replicated and extended using additional assessment measures and time points, can provide a better understanding of how in-task and post- FRT affective response relates to meeting not only RT guidelines but also helping to accomplish MVPA concurrently.

Acknowledgements.

No external funding supported this study. The results of this study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine. The results of this study are presented clearly, honestly and without fabrication, falsification or inappropriate data manipulation.

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Buckworth J, Nigg C. Physical activity, exercise, and sedentary behavior in college students. J Am Coll Heal. 2004;53(1):28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association ACH. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment (ACHA-NCHA II) Reference Group Executive Summary–Fall 2015. Hanover, MD: Am Coll Heal Assoc; 2015; [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC - The Benefits of Physical Activity [Internet]. Vol. 2016. 2015. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health/

- 4.Ebben W, Brudzynski L. Motivations and barriers to exercise among college students. J Exerc Physiol Online. 2008;11(5):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilpatrick M, Hebert E, Bartholomew J. College students’ motivation for physical activity: differentiating men’s and women’s motives for sport participation and exercise. J Am Coll Heal. 2005;54(2):87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harne AJ, Bixby WR. The benefits of and barriers to strength training among college-age women. J Sport Behav. 2005;28(2):151. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers RS, Roth DL. Perceived benefits of and barriers to exercise and stage of exercise adoption in young adults. Heal Psychol. 1997;16(3):277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene DR, Petruzzello SJ. More isn’t necessarily better: Examining the intensity–affect–enjoyment relationship in the context of resistance exercise. Sport Exerc Perform Psychol. 2015;4(2):75. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. Acute aerobic exercise and affect. Sport Med. 1999;28(5):337–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. The relationship between exercise intensity and affective responses demystified: to crack the 40-year-old nut, replace the 40-year-old nutcracker! Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):136–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed J, Ones DS. The effect of acute aerobic exercise on positive activated affect: A meta-analysis. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2006;7(5):477–514. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petruzzello SJ, Landers DM, Hatfield BD, Kubitz KA, Salazar W. A meta-analysis on the anxiety-reducing effects of acute and chronic exercise. Sport Med. 1991;11(3):143–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauvin L, Rejeski WJ, Norris JL. A naturalistic study of the impact of acute physical activity on feeling states and affect in women. Heal Psychol. 1996;15(5):391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy CJ, Rejeski WJ. Not what, but how one feels: The measurement of affect during exercise. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1989;11(3):304–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell J A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(6):1161–78. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winett, Williams DM, Davy BM. Initiating and maintaining resistance training in older adults: a social cognitive theory-based approach. Br J Sports Med. 2009. February;43(2):114–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams DM, Dunsiger S, Ciccolo JT, Lewis BA, Albrecht AE, Marcus BH. Acute affective response to a moderate-intensity exercise stimulus predicts physical activity participation 6 and 12 months later. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2008;9(3):231–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tharion WJ, Harman EA, Kraemer WJ, Rauch TM. Effects of Different Weight Training Routines on Mood States. J Strength Cond Res. 1991;5(2):60–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekkekakis P Pleasure and displeasure from the body: Perspectives from exercise. Cogn Emot. 2003;17(2):213–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arent SM, Landers DM, Matt KS, Etnier JL. Exercise Psychology. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2005;27:92–110. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartholomew JB, Linder DE. State anxiety following resistance exercise: The role of gender and exercise intensity. J Behav Med. 1998;21(2):205–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Focht, Koltyn KF. Influence of resistance exercise of different intensities on state anxiety and blood pressure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999. March;31(3):456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koltyn KF, Raglin JS, O’Connor PJ, Morgan WP. Influence of weight training on state anxiety, body awareness and blood pressure. Int J Sports Med. 1995;16(04):266–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellezza PA, Hall EE, Miller PC, Bixby WR. The influence of exercise order on blood lactate, perceptual, and affective responses. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23(1):203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bibeau WS, Moore JB, Mitchell NG, Vargas-Tonsing T, Bartholomew JB. Effects of acute resistance training of different intensities and rest periods on anxiety and affect. J strength Cond Res. 2010. August;24(8):2184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinrich KM, Patel PM, O’Neal JL, Heinrich BS. High-intensity compared to moderate-intensity training for exercise initiation, enjoyment, adherence, and intentions: an intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson WR. Worldwide survey of fitness trends for 2018: The CREP Edition. ACSM’s Heal Fit J. 2017;21(6):10–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brill PA. Exercise your independence: Functional fitness for older adults. In: Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2008. p. S88–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lagally KM, Cordero J, Good J, Brown DD, McCaw ST. Physiologic and metabolic responses to a continuous functional resistance exercise workout. J Strength Cond Res. 2009. March;23(2):373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss T, Kreitinger J, Wilde H, Wiora C, Steege M, Dalleck L, et al. Effect of functional resistance training on muscular fitness outcomes in young adults. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2010;8(2):113–22. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Focht Brian C., Garver Matthew J., Cotter Joshua A., Devor Steven D., Lucas Alexander R., and Fairman CM. Affective Responses to Acute Resistance Exercise Performed at Self-Selected and Imposed Loads in Trained Women. 2015;29(11):3067–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Can J Sport Sci. 1992; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chek P Movement That Matters. San Diego: C.H.E.K. Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borg G Borg’s perceived exertion and pain scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheppard J, Triplett T. Program Design for Resistance Training In: Haff G, Triplett T, editors. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning 4th Edition. 4th ed Human kinetics; 2015. p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buckley JP, Borg GAV. Borg’s scales in strength training; from theory to practice in young and older adults. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36(5):682–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Focht Garver, Cotter Devor, Lucas Fairman. Affective Responses to Acute Resistance Exercise Performed at Self-Selected and Imposed Loads in Trained Women. 2015;20(3):658–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs G. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (form Y): self-evaluation questionnaire. Consulting Psychologists Press Palo Alto, CA; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ . Physical activity enjoyment scale: Two validation studies. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1991;13(1):50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raedeke TD, Focht BC, Scales D. Social environmental factors and psychological responses to acute exercise for socially physique anxious females. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2007;8(4):463–76. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bixby W, Spalding T, Hatfield B. Temporal Dynamics and Dimensional Specificity of the Affective Response to Exercise of Varying Intensity: Differing Pathways to a Common Outcome. Exerc Psychol. 2012;23(3):171–90. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ginis KAM, Bassett-Gunter RL, Conlin C. 4 Body Image and Exercise. Oxford Handb Exerc Psychol; 2012;55. [Google Scholar]