Abstract

In the developing world, traditional social networks of exchange and reciprocity are critical components of household security, disaster relief, and social wellbeing especially in rural areas. This research asks the question: How are traditional social networks of exchange related to emerging household strategies to diversify livelihoods? Within this context, this study uses a mixed methods design to examine the character of inter-household exchanges of material goods (IHE) and the association between IHE and livelihood diversification, in ethnically Maasai communities in northern Tanzania. Findings show that IHE are both evolving and declining and are negatively associated with livelihood diversification.

1. INTRODUCTION

Social networks, and the various forms of social capital they confer on their members, have been extremely popular areas of social research in the recent past (Borgatti et al., 2009; Freeman, 2004; Watts, 2004; Woolcock & Narayan, 2000). Within this large body of research much focus has been on characterizing the structure and function of networks and examining the consequences of social networks for individual outcomes (Borgatti et al., 2009; Newman, 2003). Fewer studies have focused on how social networks evolve in response to outside factors (Newig et al., 2010; Ostrom, 1990) and, furthermore, what the implications of this evolution may be for household- and community-level risk management, vulnerability and development. In the developing world, where social welfare projects are absent or limited, social networks are critical components of household security, disaster relief, and social wellbeing, especially in rural areas (Fafchamps, 1992; Woolcock & Narayan, 2000). Of special importance are networks wherein the exchange of material goods1 helps to alleviate food insecurity (Aktipis et al., 2011; Johnson, 1999), smooth consumption (Fafchamps et al., 1998; Kazianga & Udry, 2006; Rosenzweig & Stark, 1989) and raise funds to address other concerns including health issues (Befu, 1977; Ensminger, 2002). Ultimately, networks of this kind serve to manage risk and reduce vulnerability within communities and may serve many other purposes including supporting the capacity for collective action (Adger, 2003; Reynolds et al., 2003). Despite the importance of social networks in this context, much remains unknown about how traditional networks of exchange in subsistence economies are changing in response to the growing importance of household economic diversification (Barrett et al., 2001; Homewood et al., 2009; Little et al., 2001; McCabe et al., 2010).

This paper seeks to build on these studies by focusing on the traditional mechanisms of social support and reciprocity that undergird longstanding social networks among a subsistence society in the midst of economic change. To do so, it views exchange of material goods between households as: (1) historically important sources of household security and community cohesion, which serve to manage risk, respond to shocks, and enable collective action across scales; and (2) at risk of widespread decline as households pursue individualized, diversified portfolios of economic activities. Specifically, this paper examines the character of inter-household exchanges of material goods (IHE) and the associations between IHE (including current incidence and perceived trends) and household strategies to diversify income streams in ethnically Maasai, agro-pastoral communities in northern Tanzania.

2. CONCEPTUAL APPROACH

In this paper, we offer a conceptual approach which views: (1) IHE as a set of traditional strategies in Maasai society to build social networks and manage risk and uncertainty; and (2) livelihood diversification (LD) as set of emerging strategies in Maasai society to manage risk and uncertainty. This approach supports several competing hypotheses:

H1. The two may be inversely related. Since LD and IHE each function to manage risk, the rise in LD is associated with a reduction in IHE.

H2. The two may work in concert. Since LD has opened up new pathways of economic activity, including new partners, and new material goods, its rise is associated with an increase in IHE.

H3. New constraints and opportunities associated with LD affect different exchange mechanisms in different ways.

H4. Despite functional similarities between IHE and LD, IHE is deeply engrained in Maasai social organization and is correspondingly unaffected by changes in LD.

While there may be reasons to hypothesize that Maasai would seek to combine the risk management benefits of LD and IHE (H2), it may be more likely that the trends towards individualization that are evident in the Maasai (transitions from commonly managed land to private land tenure and from reciprocal labor to wage-labor) will also be evident in approaches to manage risk – and therefore tradeoffs will exist between IHE and LD (H1). However, this may be the case in some contexts but not in others (H3). Given this range of possible outcomes, this paper provides an empirical test of these hypotheses.

Importantly, we do not view the potential transition from one form of risk management to another as trivial. Each form carries with it unique implications for a wide range of outcomes including: vulnerability to different types of shocks (i.e, low/high incidence vs, low/high severity), utilization of natural resources and resulting environmental degradation, capacity for collective action, and exposure to opportunities and constraints associated with inclusive vs. exclusive social networks. Regarding social networks more broadly, we also view shifting risk management strategies as a potential signal for a more wholesale social network transition. These considerations are reviewed in greater detail in the discussion section.

(a). Social networks of exchange

Broadly defined, social networks are structures of individuals or institutions, which are held together by some form of interdependency. They have become a major area of interest in several fields across the social sciences (Watts, 2004). In 2009, Borgatti noted that the number of papers in the Web of Science on “social networks” nearly tripled in the preceding decade (Borgatti et al., 2009). This is not surprising given the diversity of ways in which social networks facilitate the production and exchange of information and material goods at various scales. The history of network analysis in the social sciences is quite well reviewed elsewhere (Borgatti et al., 2009; Freeman, 2004; Mitchell, 1974; Watts, 2004). Reviews have showed that researchers have been especially concerned with the structure of social networks including issues of centrality, connectedness, openness, and density (e.g., Bodin & Crona, 2009; Granovetter, 1985; Granovetter, 1973; Wolfe, 1978). Borgatti points out that while there have been many studies of the determinants, or antecedents, of network connections, the “primary focus of network research in the social sciences has been on the consequences of social networks” (2009, 894).

One avenue of scholarship on the consequences of social networks has focused on natural resource management and governance (Bodin et al., 2006; Bodin & Crona, 2009; Ostrom, 1990; Pretty, 2003). Some have argued that social institutions and networks are important components of social capital and adaptive capacity (Folke, 2006; Ostrom, 2005; Ostrom & Ahn, 2003; Walker et al., 2006) and are central to strategies to protect biodiversity (Agrawal & Gibson, 1999; Pretty & Smith, 2004; Pretty & Ward, 2001) and adapt to changes in natural capital brought about by climate change (Adger, 2003). Others have claimed that some network structures are more supportive of equitable and effective management than others (Bodin & Crona, 2009; Newman & Dale, 2005).

Many recent empirical studies on social/ecological systems (SESs) have focused on the role of social networks in shaping governance outcomes in the developing world (Bodin & Crona, 2008; Gelcich et al., 2010; Prell et al., 2009; Stein et al., 2011; Tompkins et al., 2002). In doing so, they have tended to focus on information exchange and collective action to manage resources and/or resource crises. Fewer studies have focused on the exchange of material goods between individual actors or households - a particularly salient issue where the subsistence strategies for rural households in developing countries include the harvesting, consumption, and exchange of natural resources and consequently hold profound implications for resource management and biodiversity conservation.

As with social networks, the history of scholarship on social exchange is extensive and very capably discussed elsewhere (Befu, 1977; Mauss, 1990; Sahlins, 1972; Scott, 1976). Research in development economics on agrarian societies has focused on exchanges and/or transfers to manage risk. Much of this research has focused on the effect of structural characteristics of social networks on risk-sharing outcomes (Ambrus et al., 2010; Attanasio et al., 2012; Bloch et al., 2008), and the efficacy of transfers (public and private) on risk pooling and income (Cox & Fafchamps, 2007; Pan, 2009). Studies focused on the determinants of social networks of exchange and insurance have identified geographic and social proximity (Fafchamps & Gubert, 2007), shocks (Fafchamps & Lund, 2003), income (Santos & Barrett, 2006) and altruism (De Weerdt & Fafchamps, 2011) as important factors.

It is unfortunate that the recent surge in scholarship on the effects of social networks, risk management, and natural resource utilization has not more directly engaged the work in anthropology and sociology on material exchange and moral economies (Thompson, 1971), though some exceptions exist (Reynolds et al., 2003). In addition to providing households with needed material goods especially food, exchanges between households create networks of reciprocity, trust, and support (Ensminger, 2002). Hunt has distinguished between exchange and transfer, where exchanges involve reciprocity and transfers do not necessarily (2002). In the context of this study, transactions involve the expectation of reciprocity, as we will describe below, and therefore we refer to them as exchanges throughout the paper.

In East Africa, pastoralist and agro-pastoralist societies provide vibrant examples of how social networks and material exchange are integral to social/ecological systems and natural resource management (Homewood, 2008; Homewood & Rodgers, 1991; Little & Leslie, 1999; McCabe, 2004). Furthermore they offer productive comparisons with strictly agrarian societies for which mobility and common property management are less common risk management strategies.

Exchange within pastoralist groups can take many forms and often supports the persistence of existing land use practices. While exchange traditions are institutions driven by many factors, including the forces of cultural inertia and history (Hodgson, 2004), perhaps the most common function of exchange articulated in the literature on pastoralist communities is that they are mechanisms to pool risk and promote security and stability in the face of uncertainty (Aktipis et al., 2011; Bollig, 1998; Cronk, 2007; McCabe, 1990b; Moritz, 2013). Households may form networks with each other to insure against loss from a number of concerns including drought and disease. Another function of exchange networks is their role in promoting herd and family development (Aktipis et al., 2011; de Vries et al., 2006; Johnson, 1999). Through various types of networks, an individual can acquire wives for himself or his sons and diversify the species in his herd. And through the development and growth of his herd and his family (which provides the labor to manage the herd, among other things) an individual can reduce the chances that future losses will require assistance from his network. In this way, exchange networks serve to promote the independence of the household at the same time that they provide the promise of support in times of need.

Despite the ubiquity and functionality of exchange networks in contributing to ex ante risk mitigation strategies and ex post risk coping strategies, few studies have examined the effect of LD on social networks of exchange. LD itself is understood as a means by which households can manage their exposure to risk and cope with adverse circumstances (Barrett et al., 2001; Ellis, 2000). This raises questions about the relationship between LD and social networks of exchange in agro-pastoralist societies specifically and about functional redundancy in social networks more generally.

(b). Livelihood diversification

Defined simply, LD is the “process by which rural families construct a diverse portfolio of activities and social support capabilities in order to survive and to improve their standards of living” (Ellis, 1998, 4). The effect of LD as an instrument of risk management has been framed in the language of “push” and “pull” factors (Barrett et al., 2001) wherein households facing adverse circumstances are pushed into LD and households responding to opportunities (which in some cases may be opportunities to reduce future exposure to risk) are said to be pulled into LD. Functionally, these justifications are closely aligned with those that shape decisions to participate in social networks of exchange, yet little scholarship has examined this.

Much of the literature on LD has focused on its determinants (Barrett et al., 2001; Ellis, 2000) with fewer studies examining the role of diversification as a predictor, or independent variable (Bezu et al., 2011; Bigsten & Tengstam, 2011; Caviglia-Harris & Sills, 2005). The literature on LD among pastoralists and agro-pastoralists follows these trends. While many studies have focused on the drivers of LD, including land privatization (Galaty, 1994; Homewood, 2004), NGO sponsored development (Igoe, 2003), education (Berhanu et al., 2007), market integration (Little, 2003) and biodiversity conservation (Baird & Leslie, 2013; Homewood et al., 2009), less research has been done on outcomes driven by LD among pastoralists. Important exceptions to this include research on the effect of LD in shaping family size (Hampshire & Randall, 2000) and livestock management activities (McCabe et al., 2010).

As noted above, few studies have investigated the relationship between social networks of exchange and LD. Cinner and Bodin (2010) have used social network analysis to examine how the structure of social networks of natural resource users affects patterns of LD. They found that diversified resource users, connected through networks that span occupational fields, tend to specialize as development occurs, but that communities remain economically diversified. Many opportunities, however, to examine these and other issues remain.

Following the opportunities to integrate the fields of study on social networks and LD, this study seeks to understand the character of IHE among Maasai households in Simanjiro District, northern Tanzania. Furthermore, it seeks to understand how IHE has changed and how LD at the household level is associated with IHE. Along these lines, the study investigates two research questions (RQs):

RQ1. What are the primary instruments/mechanisms of IHE? How are they used? How are they changing?

RQ2. What is the effect of LD on IHE, controlling for other factors?

3. STUDY SITE

Simanjiro District in northern Tanzania is well suited to investigate the relationship between LD and social networks. The communities in Simanjiro are ethnically homogenous, have traditionally maintained elaborate networks of exchange (Aktipis et al., 2011; Homewood & Rodgers, 1991), and are in the process of diversifying their livelihoods (Baird & Leslie, 2013; Cooke, 2007; Homewood et al., 2009).

The district, which is located within the Tarangire-Manyara Region, is one of the most diverse grassland ecosystems on the planet (Olson & Dinerstein, 1998) and has been the focus of intense biodiversity conservation efforts for decades. A central feature in the region is Tarangire National Park (TNP), which lies immediately to the west of Simanjiro District. Before the park was established, the areas that are now Simanjiro District and TNP comprised portions of the traditional territory of the Kisongo Maasai (Igoe, 1999). This group’s economic activities traditionally centered on transhumant pastoralism, a culturally engrained activity well suited to this area’s semi-arid climate and high degree of rainfall variability (Ellis & Swift, 1993; Homewood & Rodgers, 1991). In the past few decades, however, Maasai throughout East Africa have begun to adopt agriculture for various reasons (Baird & Leslie, 2013; Baird et al., 2009; Cooke, 2007; McCabe et al., 2010; Nkedianye et al., 2009; Sachedina & Trench, 2009; Trench et al., 2009). More recently, some Maasai have begun to adopt other livelihood activities including labor migration to urban centers, local non-farm employment, and sharecropping (Baird & Leslie, 2013; Baird et al., 2009; Homewood et al., 2009).

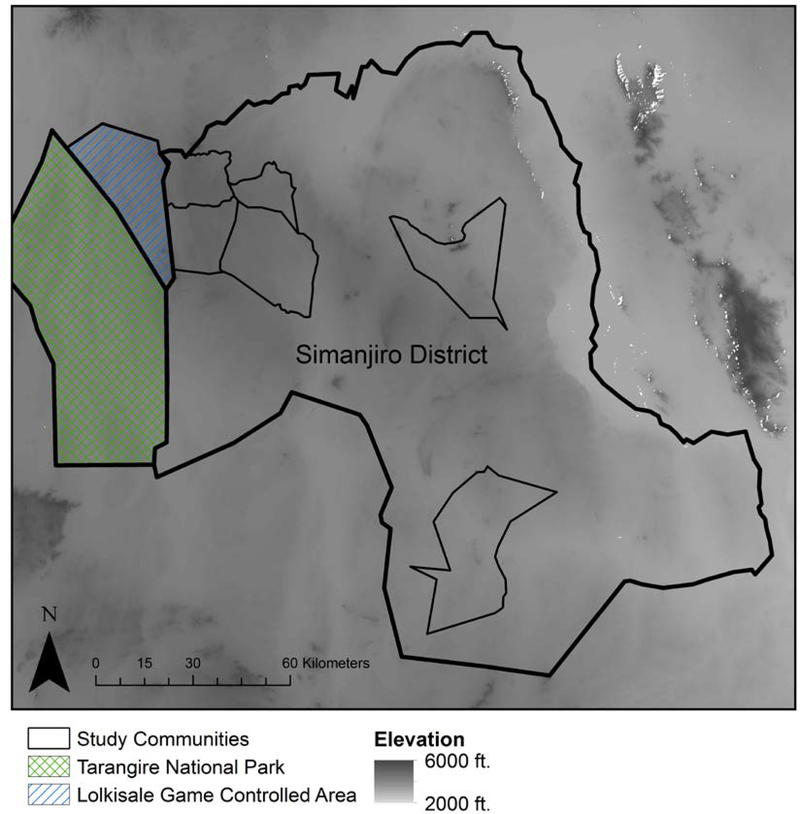

Much of the research on this area has focused on the social dynamics of biodiversity conservation (Davis, 2011; Goldman, 2009; Igoe, 2002). In fact, this study is part of a larger study of the effect of TNP on community development and livelihood change in Simanjiro District. Six ethnically Maasai communities are included in the study (see Figure 1). Communities were originally selected to highlight proximity to TNP. Two communities are located adjacent to the park, two are near the park but not adjacent, and two are located far from TNP. Earlier findings from the larger study have shown a positive association between LD and proximity to TNP (Baird & Leslie, 2013). These findings are consistent with other studies that show diversification to be a growing trend among the Maasai (McCabe, 2003) and that biodiversity conservation may be driving it in some cases (Baird et al., 2009; Trench et al., 2009). Analyses for this paper will seek to expand on these findings by examining the association between LD and IHE as will be explained below.

Figure 1.

Map of study area

4. METHODS

Multiple methods of data collection and analysis were integrated to address each research question. The primary methodological approaches utilized were semi-structured group interviews and a structured survey of households. These data collections tools are well established in the social sciences. We will first describe our use of qualitative group interviews and then the implementation of a structured household survey.

(a). Data collection

Semi-structured group interviews (n=64) were conducted with community members, administrators, and leaders in each community to: (1) assess the character and causal processes of IHE and other aspects of Maasai life; (2) inform the development of a household survey instrument to measure the incidence of IHE and other household characteristics; and (3) yield information on the monetary value of livestock and agricultural products to facilitate the conversion of survey measures (i.e., livestock holdings, agricultural yield, etc.) into monetary measures for analysis. This method allowed for open discussion around broadly framed questions about household economics and IHE as well as more targeted questions about seasonal market prices. Participants were selected for their daily participation in livestock and farming activities and knowledge of current and historical use of IHE transactions. The interviews solicited information on a range of topics including: how transaction types are different from each other; how and when each type of transaction is used; how social organization and the age-set system2 affect patterns of exchange between households; how new economic activities and material goods have been incorporated into these exchange processes; and how current trends are different now than they were in the past. All group interviews were conducted by the first author with the assistance of 1 or 2 Maasai assistants/translators.

To collect quantitative data on the incidence of IHE for use in statistical analyses, a structured household survey was implemented with 36 households in each of the 6 study communities (n=216). Data were collected on issues that included: the number and type of transactions with other households; the item exchanged; the terms of repayment (in some cases), the purpose of the exchange, the age-set of the other party, the relation of the two parties (including relatives3); and basic household demographic and economic variables. Without access to a census on which to base a strictly random sample, we sought to sample: (1) households from different community sub-villages (in rough proportion to the population of each sub-village); (2) household heads from each of the major age-sets; and (3) households representing a range of wealth statuses (in proportions approximately related to local levels of wealth). This approach, which Bernard (2006) refers to as quota sampling, reflects our best efforts to draw a representative sample. Local leaders were enlisted to assist in the identification of households meeting these sampling criteria.

By nature of the data collection strategy, these data provide extensive information on the respondent and his engagement with other parties4. They provide limited information, however, on the other parties with whom transactions were conducted. Therefore these data preclude the elucidation of several aspects of the larger exchange network structure. They do, on the other hand, provide robust information on the extent to which the respondent is engaged in local social network of exchange. This was done as a matter of necessity and intention. First, respondents were disinclined to reveal detailed information about the parties they exchanged with as many transactions are meant to be private - details about the transaction itself, however, were not off-limits. Second, by design, this study sought to examine the association between household LD and engagement in IHE. As such, the data communicate little about the characteristics of the network itself and much about individual membership in the network.

In addition to information on current IHE, the survey collected information on the respondent’s perceptions of how the incidence of IHE in the present compared to the past. In the case of perceptions of the past, questions were asked about the past generally and about the specific period around 2002–2003. This specific time period was a relatively good year for rain preceded by two poor years, and therefore resembled the recent climatic conditions at the time the survey was conducted in 2010.

Lastly, to calculate household measures of livelihood diversification, data were collected on: livestock holdings including breed types, gender and age; purchases and sales of livestock in the previous 12 months; land allocation; area of land farmed; species farmed; farming techniques; agricultural yields in 2010; non-farm employment by household members; remittances to the household; and household demography (de Leeuw et al., 1991; Homewood & Rodgers, 1991; Sellen, 2003). Surveys were conducted by trained Maasai enumerators between September and December, 2010.

(b). Data analysis

Our analysis of the dynamics of IHE proceeded in several steps as described below. The first set of qualitative analyses describe the primary mechanisms of exchange and how they are used, how they are changing, and how they are integrated into the social and economic lives of local people (RQ1). The second set of analyses use regression models to understand how LD is associated with: (1) the utilization of these exchange mechanisms; and (2) perceptions of their use compared to the past (RQ2).

(i). Description of IHE

We conducted content analysis of group interview responses to describe the primary instruments of exchange, how they are used, and how they are changing (RQ1). Specifically, we inductively coded six group interview responses using qualitative analytical software (Atlas.ti). These interviews focused exclusively on IHE. Beyond identifying the basic structure and function of exchange mechanisms, coding focused on linking the exchange mechanisms to larger social and economic processes, such as household demographics, including family creation and growth, and herd management and development – issues that are closely intertwined. Our interpretation of these interview responses was strongly supported by insights gained through other group interviews that focused on different aspects of Maasai society, including issues related to household and community social and economic processes. To provide additional context, basic descriptive statistics of IHE types and their characteristics are also displayed below.

(ii). Regression models

To examine the association between LD and: (1) current utilization of IHE; and (2) perceived incidence of IHE compared to the past (RQ2), Poisson and multinomial logistic regression models were estimated, respectively. Measures of current IHE utilization included: total number of loans (given or received); total number of restocking events (i.e., group efforts to provide poor families with needed animals) (contributed to or benefitted from); total number of gifts (given or received); and total IHE (given or received)5. Poisson models are used in these cases because each dependent variable is a count variable. Measures of perceived incidence of IHE compared to the past included perception of relative frequency of: loans; restocking; and gifts. Multinomial logistic regression was used because households provided a categorical response indicating declining, stable or increasing frequency of these activities. “Less common” is used as the reference category.

LD is represented by two variables: % of Income from Livestock, and a Herfindahl index (Rhoades, 1993). Given that the Maasai are traditionally pastoralists, households that are more diversified tend to have a lower percentage of total income coming from livestock than households that are less diversified. This measure is well established in the literature on LD in pastoralist communities (Baird & Leslie, 2013; Block & Webb, 2001; Homewood et al., 2009; Minot et al., 2006). The second variable, a Herfindahl index, is similarly a measure of concentration (i.e. the inverse of diversification). This index, which is often used to measure competition in economic sectors (Rhoades, 1993) and diversification within firms (Berry, 1971), is calculated as the sum of the squared percentage of income per source of total household income. Sources of income include income from livestock, agriculture, petty trade, wage labor, small business activities, mining, and proceeds from leased land6. Squared terms of each measure of LD were included in the models to test for nonlinearity. In total, we estimated four specifications of our models: (S1) a linear measure of % of income from livestock; (S2) linear plus squared terms of % of income from livestock; (S3) a linear measure of the Herfindahl index; and (S4) linear plus squared terms of the Herfindahl index. Controls included characteristics of the household head (i.e., age and age squared, education and church membership) and of the household (i.e., measures of household size7, per capita wealth, acres allocated, total income). Our small sample of communities (n=6) limits our ability to statistically address contextual effects on IHE. Despite this limitation, we were able to add a control for proximity to TNP, which has been linked to LD in this area (Baird & Leslie, 2013). Descriptions and means of the variables used in each set of regressions models are presented in Table 1. All models are adjusted for clustering at the level of the community (Angeles et al., 2005), which corrects for any community-level correlation arising from the clustered sampling strategy.

Table 1.

Descriptions of variables used in regression analyses.

| Variable | Description | Mean (Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||

| Number of loans | Number of loans given or received by the respondent in the 12 months prior to the survey. | 1.46 (2.1) |

| Number of restocking events | Number of restocking events contributed to or received by the respondent in the 12 months prior to the survey. | 0.71 (1.2) |

| Number of gifts | Number of gifts given or received by the respondent in the 12 months prior to the survey. | 1.74 (1.9) |

| Number of IHE | Total number of loans, restocking events and gifts given/contributed to or received by the respondent in the 12 months prior to the survey. | 3.97 (4.0) |

| Perception of loan trends | ||

| Less common (0/1) | Perception that the use of loans was less common in 2009–2010 (the time period captured the survey) than during the period 2002–2003. | 0.23 |

| As common (0/1) | Perception that the use of loans was as common in 2009–2010 (the time period captured the survey) than during the period 2002–2003. | 0.50 |

| More common (0/1) | Perception that the use of loans was more common in 2009–2010 (the time period captured the survey) than during the period 2002–2003. | 0.27 |

| Perception of restocking trends | ||

| Less common (0/1) | Perception that the use of restocking was less common in 2009–2010 (the time period captured the survey) than during the period 2002–2003. | 0.27 |

| As common (0/1) | Perception that the use of restocking was as common in 2009–2010 (the time period captured the survey) than during the period 2002–2003. | 0.50 |

| More common (0/1) | Perception that the use of restocking was more common in 2009–2010 (the time period captured the survey) than during the period 2002–2003. | 0.23 |

| Perception of gift trends | ||

| Less common (0/1) | Perception that the use of gifts was less common in 2009–2010 (the time period captured the survey) than during the period 2002–2003. | 0.19 |

| As common (0/1) | Perception that the use of gifts was as common in 2009–2010 (the time period captured the survey) than during the period 2002–2003. | 0.58 |

| More common (0/1) | Perception that the use of gifts was more common in 2009–2010 (the time period captured the survey) than during the period 2002–2003. | 0.23 |

| Household head (HHH) controls | ||

| Age | Age of HHH | 47.0 (13.2) |

| Church (0/1) | Measure of HHH membership in church (Lutheran, Roman Catholic, Pentecostal, Islam, Other) | 0.72 |

| Education (0/1) | Measure of whether or not the HHH had any formal education (i.e., attended school). | 0.38 |

| Household (HH) controls | ||

| AE | Adult Equivalent Units (measure of HH size that combines members of different ages and genders to compare provisioning requirements across households)(Homewood & Rodgers, 1991; Sellen, 2003)a. | 8.97 (5.8) |

| TLU/AE | Measure of per capita livestock holding. Equal to Tropical Livestock Units (TLU – measure of livestock holdings that accounts for differences across speciesb) divided by AE (measure of household size – see above). | 5.35 (6.2) |

| Land allocation | Measure of the number of acres formally allocated to household by community for private use as of 2010. | 28.68 (29.0) |

| Total income | Total HH income from the sale of livestock, estimated value of milk off-take (incl. milk used and sold)c, estimated value of total agricultural harvest, remittance income, off-farm income, and income from leased lands in the 12 months preceding the survey interview. (Mean and standard deviation reported in US dollars.) | 2690 (3042) |

| Adjacent to park (0/1) | Measure of whether or not the HH was located in one of the two study communities located adjacent to TNP. | 0.35 |

| Livelihood diversification measures | ||

| % Income from livestock | Percent of total income from the sale of livestock and estimated value of milk off-take in the 12 months preceding the survey interview. | 0.65 (0.28) |

| Herfindahl index | Measure of concentration, or the inverse of diversification. It is calculated as the sum of the squared percentage of income per source of total household income. Sources of income include income from livestock, agriculture, petty trade, wage labor, small business activities, mining, and proceeds from leased land. | 0.64 (0.21) |

| Nhouseholds | 208 |

Adult Equivalents (AE) is a measure of a group of people expressed in terms of standard adult reference units, with respect to food or metabolic requirements. An adult male serves as the reference adult with other categories measured as fractions of that reference: adult male = 1 AE; adult female = 0.9 AE; male/female 10–14 years = 0.9 AE; male/female 5–9 years = 0.6 AE; infant/child 2–4 years = 0.52 AE.

Tropical Livestock Units (TLUs) are defined here as: 1 adult zebu cow = 0.71; adult sheep/goat = 0.17 (Homewood et. al, 2009).

Milk used and sold, or milk off-take, was calculated from our herd demographic data (according to metrics outlined by others (de Leeuw et al., 1991). Our resulting estimate for average off-take per AE per day, which is both a function of calves (a reliable proxy for lactating females) and household per capita wealth (which shapes the percent of lactating cows actually milked as well as the off-take per cow), for our sample (486 grams) was remarkably similar to observed off-take from the study area (462 grams) in 2005–2006 (Sachedina, 2008). The value of off-take was calculated from observed prices of milk (in US $) in the study area, also from Sachedina (2008).

A final consideration with our modeling is the nature of the relationship between IHE and livelihood diversification. We argue that LD can be considered as exogenous to IHE in this context because LD has been largely driven by changes in the macro-scale political economy including land tenure insecurity and privatization (BurnSilver, 2007; Galaty, 1994; Homewood, 2004), increased integration with markets and education (Ensminger, 1996; Little, 2003), and increased exposure to the diets and livelihood strategies of other ethnic groups (McCabe, 2003; McCabe et al., 2010). Furthermore, in the qualitative findings below, we identify no mechanism by which traditional practices of exchange could have led to the widespread adoption of novel and non-traditional livelihood activities such as agriculture.

(c). Strengths and weaknesses of the approach

The methodological approach described above has several strengths. First, mixed methods of data collection and analysis provide detailed qualitative information about IHE and how and why they have changed, as well as quantitative data on the present use of IHE and perceived incidence of IHE compared to the past. Many studies of social dynamics focus on qualitative descriptions of causal mechanisms and change or they focus on incidence of phenomena and statistical associations. Few are able to do both. Second, this study uses perceptions of change to get at historical conditions and therefore can comment on longitudinal change despite the use of cross-sectional data. This particular strength is supported by the consistency of the qualitative accounts of change and the quantitative measures of perceived change. Third, this study examines two separate measures of LD.

The central weaknesses of this approach are that the sample size is small, the sampling strategy was not random, and the study was cross-sectional. Mean measures of household wealth obtained in this study, however, are consistent with measures from much larger studies of Maasai households in Tanzania that utilize random samples (Homewood et al., 2009), suggesting that this sample is not necessarily skewed with regards to wealth.

5. FINDINGS

(a). Descriptions of inter-household exchanges (IHE)

The primary mechanisms by which households in the study area exchange material goods are lending, restocking, and gift giving8. In addition to being identified through informal interviews early in the data collection process, these general categories are established in the literature (see Aktipis et al., 2011; Homewood & Rodgers, 1991). Here we will present findings from qualitative group interviews about how each mechanism is used and how it has changed from the past. Also, basic descriptive statistics are presented for each mechanism.

(i). Lending

Loans are contractual agreements based on trust and arranged verbally between two parties (generally household heads) whereby a material good is provided to the borrower by the lender and a date and form of repayment are specified. Loans are private arrangements between the parties and are only extended in the event that the borrower is facing a particular problem. That is, loans are not extended for the expressed purpose of speculation by the borrower. There are two general types of loans: loans where the item transacted is kept and put to use by the borrower, and loans where the item is sold to generate cash with which to address the problem. Typical problems that may drive a borrower to seek out a lender include: herd losses from drought, disease, and/or predation sufficient to inhibit the provision of food to the household; family medical emergencies requiring expensive care; and other problems requiring cash.

Currently, as in the past, loans between households are generally given and repaid in the form of livestock. In these transactions, repayment typically includes the principle plus interest. Consequently, animals of lesser value are loaned and those of greater value are repaid. Because of their capacity to reproduce, female animals are more valuable than males. Male animals, therefore, are often given as loans and female animals are used to repay the loan. For example, a loan of an ox would be repaid with a heifer, because a heifer is more productive and therefore more valuable. Similarly, a female sheep would be used to repay a loan of a ram. In other cases, a loan of a goat or sheep may be repaid with a cow if an appropriate goat or sheep is not available. (In this case the repayment would be too great and the lender would give back another sheep or goat to even the deal.) This creates an incentive for the lender to take on the risk of lending and can also serve as a strategy for herd development. In one group interview, respondents indicated that because loans of male goats can be repaid with immature oxen, one can “build a herd using goats.” In other words, by focusing on goats, which reproduce quickly, a household head can subsequently expand the diversity and value of his herd by extending loans to others. Furthermore, since the acquisition of wives in Maasai society is dependent on the transfer of bride-wealth from the groom’s family to the bride’s family, traditionally in the form of livestock, herd growth is a necessary precursor to family growth.

For the borrower, loans are an important tool to maintain family affairs in the face of hardship. For most subsistence societies, problems often require cash (i.e., for medical expenses, etc.). For Maasai, who commonly store wealth on the hoof, problems often require the sale of animals to raise cash. If the sale of animals would render the household food-insecure, then a loan may be necessary. In this case, the borrowed animal would be sold, and the cash used to address the problem.

(ii). Restocking

Restocking is similar to lending in that it has traditionally been used when a household faces a problem, generally when a household has lost most or all of its livestock to drought, disease, or predation and the household head can no longer provide for his family. Unlike loans, however, restocking involves the transfer of material goods (generally several animals) from multiple individuals to the troubled household making this type of exchange more public than lending. Furthermore, items (generally livestock) are not loaned, but gifted, and therefore repayment is not involved, though recipients are expected to contribute to restocking efforts for other households when future needs arise. Smaller restocking events, typically for smaller families, may be taken care of within the homestead9 of the receiving household. With larger households, however, leaders typically organize restocking events and contributors are recruited from within the larger clan10.

Group interviews with participants noted that the primary purpose of restocking was to support and provision the family, especially children. In some cases, household heads may liquidate the household herd to support unhealthy behaviors, particularly drinking. In a case like this, a clan member would be appointed to oversee the restocked animals. As one respondent stated, “the clan wants to take care of children, not drunks.” In some cases, restocking is used to provide animals to households with unmarried sons who are seeking wives but lack sufficient bride-wealth. In a situation like this, not having a wife is considered a problem and restocking is therefore appropriate – though only for the first wife. Individuals cannot receive restocking support to acquire subsequent wives. Given these examples, it can be seen that, for the receiving party, restocking is an instrument that supports both the maintenance of the household and even its establishment.

(iii). Gift giving

Gift giving is the most versatile of the three exchange mechanisms and is different from lending and restocking in many ways. Perhaps most importantly, unlike lending and restocking, which traditionally are only used in the event that the receiving party has a specific problem, gifts can be given for a number of reasons which include but are not limited to addressing a specific problem. Other reasons for giving gifts are centered on establishing friendships between individuals. In Maasai society, friendships are generally solidified through the transfer of a gift from one party to another. Once established, friendships extend and strengthen an individual’s social network. Social networks, which may be comprised of family, clan, and age-set members as well as friends, are the foundation of a household’s support system and the first people to which a household will turn when it confronts problems and is in need of assistance. In this way, gifts can be seen as tools to extend the household’s safety net.

Unlike loans, gifts are very public forms of exchange, with parties generally giving each other nicknames that serve as reminders of the gifts. Typically, these nicknames are simply the name of the item gifted (i.e., goat, heifer, etc.) and replace birth names in everyday interactions between the parties. The nicknames are meant to demonstrate publicly the formality of the friendship and often they will be passed down to the children of the parties. Gift giving is a common and even expected tool of social networking. As one respondent noted, “It’s not good to call someone from your age-set by his name. You need to give the gift…” and use the nickname.

Another distinguishing characteristic of gifts is that they can be either solicited or unsolicited. In the case of unsolicited gifts, one individual will offer a gift to another individual. As noted above, the individual receiving the gift may or may not have a problem that needs to be addressed. In the case of solicited gifts, an individual will ask another individual for a gift and upon receipt of the requested gift will invite the giver to “follow the gift”. This means that the giver is invited to come to the friend in the future when he needs or desires a gift and the receiver will be there to reciprocate. Even with unsolicited gifts, the expectation is that the giver will, at some point in the future, “follow the gift” and ask for something. Interview respondents said that gifts are very much like loans (i.e., a good is exchanged in the present with the expectation that a reciprocal good will be exchanged in the future) except that there is no contract with gifts as there is with loans. Common gifts include various species of livestock, carved sticks, and blankets. Even daughters are gifted – with one man’s daughter becoming another man’s wife11.

Given their flexibility, it is not surprising that gifts are used in wide variety of situations. Elders may use gifts to reward the obedience of younger generations. For example, an elder may ask a young person to move the elder’s herd a long distance to find water or to perform some other task. The youth honors the elder by obeying and may be given a gift to mark their relationship. A similar tactic may be used by an elder who wants a certain young man to marry his daughter in the future. In this case, the elder may ask the youth for a gift “to see his obedience first,” as one respondent put it. This use of gifts to prospect for sons-in-law and facilitate marriage is common. In fact, elders may extend gifts to each other in the hope of arranging a daughter for one of their sons. In some cases, gifts are used to prospect for children. In the event that a household head is sterile he may ask his brother to lay with his wife. Any resulting children will belong to the head and for his service the brother will typically be given a heifer as a gift. In other cases, gifts are used to establish strategic relationships with others to support future herd maintenance and growth. When a gift is given, however, it’s not always clear what reciprocal gift may be coming in the future. In some cases an individual may give one cow as a gift at one point and receive multiple cows in the future. But, as was noted above, gifts are not contracts. As one community member put it, “you have to follow every gift – but it’s not a contract. You could follow it and get nothing.”

(iv). Changes from the past

The descriptions of lending, restocking, and gift giving offered above present an overview of these mechanisms and how they have traditionally been used. Here we will present findings from qualitative group interviews on how IHE have been changing in response to the increasing incorporation of agriculture into household economic activities as well as the increase in development more generally.

The rising dependence on agriculture among the Maasai over the last few decades has affected IHE in a number of ways. According to respondents, the inclusion of agricultural products in IHE began as soon as cultivation became common. Gifts and loans of maize are now used to move harvest output from households with surpluses to households with shortages. An individual may have a productive year on his farm while others do not and using loans and gifts he can distribute his surplus maize to households in need. Then, in the future, when his farm doesn’t perform well, he has people to go to for help. This is particularly helpful given the highly variable spatial distribution of rainfall in this area within and between years.

The use of agricultural products (generally 100kg bags of maize) in Maasai lending and gift-giving culture does vary in notable ways from more traditional exchanges. In the case of loans, interest payments are not typically included in repayment as is the case with livestock. When we asked why this was the case, one respondent said, “we don’t slaughter maize.” Furthermore, with agricultural gifts, nicknames are not used following the exchange as they are with other types of gifts.

Changes associated with development have brought new opportunities and constraints that have affected the use of IHE. Traditionally, restocking and loans were reserved for problems or crises only. One respondent pointed out that “you can’t get a loan or restocking if you don’t have a problem.” But now in some communities lending, restocking, and gift giving are being used to help households capture opportunities – especially educational opportunities. Students who have passed their primary school exams and are eligible for secondary school face stiff fees. To cover school related expenses, households may be forced to sell many animals. This burden is too great for some families and many students forgo secondary education for lack of funds. In some cases, however, friends, clan members, and others have supported the family through restocking, gifts, and/or loans so that the student could continue his/her education. This is a relatively new, uncommon phenomenon but seems to be more common in communities near TNP.

School construction and the attending increase in student enrollment (Baird, 2014), which in some cases is supported by exchange mechanisms mentioned above, are introducing new constraints on exchange networks. For example, young women, many of whom are enrolled in school and are embracing aspects of the developed world, do not want their fathers to decide who they will marry. Describing the challenges that he faces in asking for gifts one father said, “I can’t always give daughters now because they want to choose.” According to interview respondents, this has undermined gift giving culture. Now that young people can’t expect a wife in return, elders say that is it harder to get them to obey. “Obedience disappeared!” For these and other reasons, group respondents felt like gift giving was less common than is used to be.

Issues of “obedience” are closely related with more general concerns regarding trust in several of the study communities. In group interviews, respondents noted that people do not trust each other now as they did in the past. They attributed this to a number of things including population growth and an increase in the incidence of loans that are not repaid – “there are some cheaters now”. It is more difficult now, they claimed, to have faith in a borrower and therefore some loan requests are simply denied. In the past, however, people didn’t refuse loans. People “were just waiting for the cow’s stomach”. That is, they were freely extending loans and waiting for cows to give birth so that the loan could be repaid. In the past, respondents claimed, you didn’t need to know people well to lend to them. Now, friendship (marked by gift exchange) is often a necessary prerequisite for lending. Ultimately, people are more cautious now and only extended loans to people they know well.

(v). Descriptive statistics for loans, restocking and gifts

Our survey respondents reported data on 846 IHE transactions. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for these transactions. Statistics are reported for each transaction type (i.e., loans, restocking, gifts), stratified by whether the transacted item was given or received and stratified by percent of income in the form of livestock for the respondent’s household. For each combination of transaction type, transaction direction (i.e., given or received) and income from livestock strata (i.e., low, medium, high), the number and percent of each transaction item (i.e., livestock, maize, other) is presented along with the average age-set direction (e.g., transaction from younger age-set to older age-set). In the case of loans, the average payback period (in months) is also reported. And in the case of gifts, the percent of transacted items requested and items for a problem are also each reported.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of IHE.

| Percent of Income from Livestock |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | TOTAL | |

| Loans given | ||||

| in Livestock, n (%) | 96 (88) | 52 (88) | 19 (66) | 167 (85) |

| in Maize, n (%) | 10 (9) | 1 (2) | 5 (17) | 16 (8) |

| in other, n (%) | 3 (3) | 6 (10) | 5 (17) | 14 (7) |

| Age-set Directiona | YO | = | OY | = |

| Avg. Payback (months) | 8.0 | 9.4 | 7.6 | 8.3 |

| Loans received | ||||

| in Livestock, n (%) | 46 (75) | 29 (81) | 13 (76) | 88 (77) |

| in Maize, n (%) | 11(18) | 4 (11) | 1 (6) | 16 (14) |

| in other, n (%) | 4 (7) | 3 (8) | 3 (18) | 10 (9) |

| Age-set Directiona | YO | = | = | = |

| Avg. Payback (months) | 7.2 | 10.3 | 10.7 | 8.7 |

| Total loans, n (%) | 170 (55) | 95 (30) | 46 (15) | 311 (100) |

| Restocking given | ||||

| in Livestock, n (%) | 67 (92) | 44 (90) | 23 (85) | 134 (90) |

| in Maize, n (%) | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 5 (3) |

| in other, n (%) | 3 (4) | 4 (8) | 3 (11) | 10 (7) |

| Age-set directiona | OY | OY | YO | OY |

| Restocking received | ||||

| in Livestock, n (%) | 5 (100) | 3 (60) | 4 (100) | 12 (86) |

| in Maize, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| in other, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) |

| Age-set directiona | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Total restocking, n (%) | 78 (48) | 54 (33) | 31 (19) | 163 (100) |

| Gifts given | ||||

| in Livestock, n (%) | 78 (91) | 44 (74) | 40 (71) | 162 (81) |

| in Maize, n (%) | 7 (8) | 11 (19) | 9 (16) | 27 (13) |

| in other, n (%) | 1 (1) | 4 (7) | 7 (13) | 12 (6) |

| Age-set Directiona | YO | = | YO | YO |

| % requested | 73 | 49 | 64 | 64 |

| % for problem | 66 | 39 | 55 | 55 |

| Gifts received | ||||

| in Livestock, n (%) | 65 (84) | 36 (76) | 36 (77) | 137 (80) |

| in Maize, n (%) | 9 (12) | 5 (11) | 9 (19) | 23 (14) |

| in other, n (%) | 3 (4) | 6 (13) | 2 (4) | 11 (6) |

| Age-set Directiona | = | OY | OY | OY |

| % requested | 61 | 40 | 34 | 50 |

| % for problem | 62 | 26 | 36 | 45 |

| Total gifts, n (%) | 163 (44) | 106 (28) | 103 (28) | 372 (100) |

| Nhouseholds | 63 | 81 | 64 | 208 |

Age-set direction is the average direction, in terms of age-set, of transaction: YO = younger (giving to/receiving from) older age-set; OY = older (giving to/receiving from) younger age-set; “=“ = approximately equal number of younger to older and older to younger transactions.

Several general findings are evident here. First, livestock comprise the great majority of transactions for each transaction type, although maize is not uncommon. Second, the average payback period for loans is 7–11 months, which is consistent across strata. Third, gifts are more often given by younger age-sets and received by older age-sets. Fourth, restocking is typically given by older age-sets. Fifth, clear age-set directions are not apparent in the case of loans. And sixth, households classified as having a higher percent of their total income coming from livestock are engaged in IHE the most.

(b). Predictors of current IHE & perceived trends

The results for the regression analysis of the association between LD and IHE (RQ2) are presented in two tables and two figures, first for current use of IHE followed by perceived changes. Our discussion below focuses on the effects of LD, but it is worth noting that the effects of the control factors are largely consistent across outcomes and consistent with expectations: participation in and perceptions of increases in IHE are typically more common among larger and more educated households with older heads and less access to agricultural land.

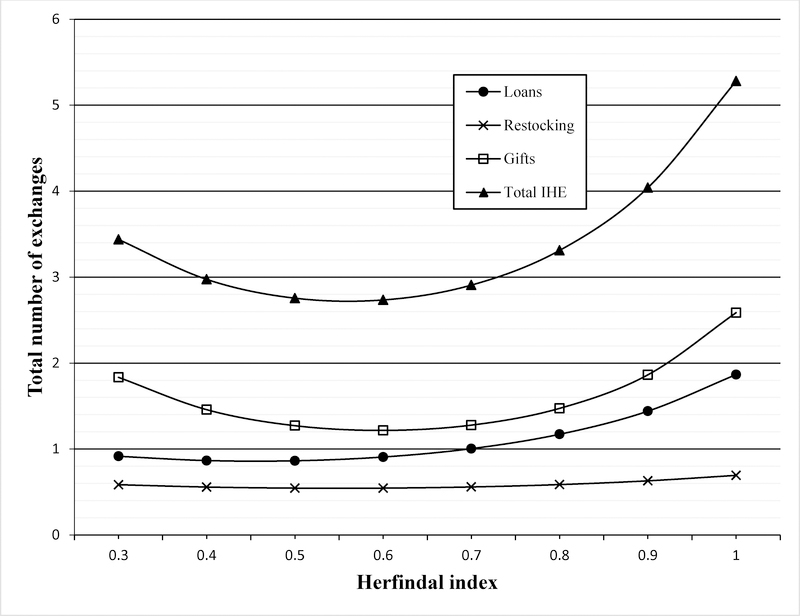

As expected, measures of LD had significant effects on the use of IHE when controlling for other factors (see Table 312). Beginning with specifications 1 and 2 (S1 and S2)13, the effect of % of income from livestock on IHE types is significant and non-linear (S2) in the case of loans and restocking, and significant and linear (S1) the case of total IHE. With specification 4 (S4), the effect of the Herfindahl index is significant and non-linear for each dependent variable. Taken together the findings presented in Table 3 reveal that the effects of LD on IHE are largely negative (i.e., the effects of concentration are positive) but that the relationship is nonlinear, with the steepest decline in IHE as income moves away from dominance by livestock. The chief exception to this pattern is restocking, where intermediate levels of % of income from livestock are associated with the highest levels of engagement in restocking. Models that disaggregate total IHE values into values for given and received tell a similar story (see Appendix 1). To further clarify these relationships, Figure 2 presents predicted values of numbers of exchanges by exchange type using the nonlinear specification of the Herfindahl index, which provided the best overall fit. This confirms that participation in IHE is lowest at intermediate values of LD. However, in the range of the Herfindahl index values where these households are concentrated (0.5–1.0), the relationship is largely positive.

Table 3.

Poisson regression models of IHE numbers (with exponentiated coefficients)

| Predictor | Num of Loans | Num of Restocking | Num of Gifts | Num of Total IHE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model specification 1 | ||||

| Household head measures | ||||

| Age | 1.11*** | 1.05 | 1.07* | 1.08** |

| Age (sq) | 1.00** | 1.00 | 1.00** | 1.00** |

| Church (0/1) | 0.93 | 1.36* | 1.16 | 1.10 |

| Education (0/1) | 1.39† | 1.06 | 1.40* | 1.32* |

| Household measures | ||||

| Ln (AE) | 1.97*** | 2.79** | 1.29* | 1.75*** |

| Ln (TLU/AE) | 1.19 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.11 |

| Ln (Land allocation) | 0.64*** | 0.92 | 0.80** | 0.75*** |

| Ln (Total income) | 1.21 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 1.14 |

| Adjacent to park (0/1) | 0.95 | 0.64† | 0.73 | 0.77 |

| Diversification measure | ||||

| % Income from livestock | 3.52† | 2.83* | 1.74 | 2.35** |

| Nhouseholds | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 |

| Model specification 2 | ||||

| % Income from livestock | 0.30 | 18.60** | 0.32 | 0.53 |

| % Income from livestock (sq) | 7.84** | 0.21* | 4.39 | 3.58 |

| Joint significance test | * | ** | ns | ns |

| Model specification 3 | ||||

| Herfindahl index | 3.11* | 1.33 | 1.70 | 2.02* |

| Model specification 4 | ||||

| Herfindahl index | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.00*** | 0.02* |

| Herfindahl index (sq) | 13.69 | 3.28 | 104.00*** | 31.20** |

| Joint significance test | * | *** | *** | *** |

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.00

Figure 2.

Predicted values of types of inter-household exchange by exchange type and household measure of livelihood diversification (i.e., Herdindahl index) with mean values of the other predictors.

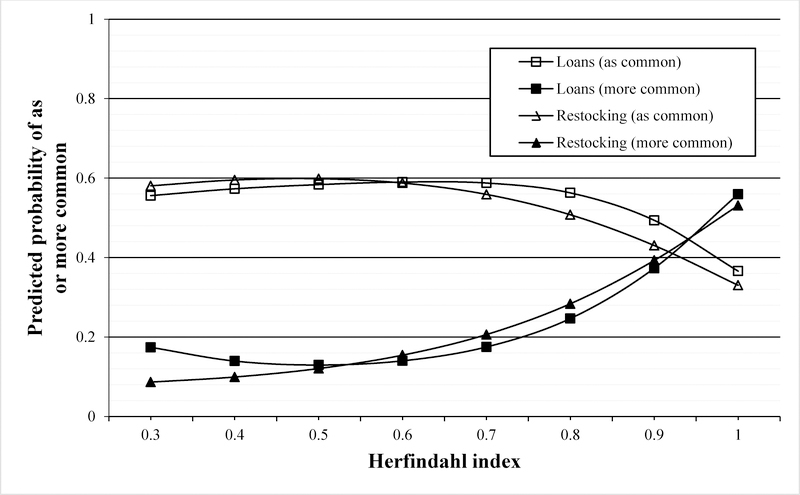

Measures of LD also had significant effects on perceived trends in IHE when controlling for other factors (see Table 4 and Endnote 12). In specifications 2 and 4, the effects of % of income from livestock and the Herfindahl index on perceived trends for loans and restocking were significant, non-linear, and similar to each other. Figure 3 presents predicted probabilities of perceiving IHE as “as common” or as “more common” in 2009–10 compared to 2002–03 for loans and restocking, which had significant nonlinear effects from the Herfindahl index. The lowest odds of ranking loans as more common at the time of the interview compared to 2002–03 were found at intermediate levels of diversification. In other words, moderately diversified households are more likely to view loans as declining rather than increasing in use. The relationship between LD and perceived trends is different in the case of restocking. The lowest odds of ranking restocking as more common than the past were found at the highest levels of diversification (i.e., low values of Herfindahl). However across the range of Herfindahl values where the sample is concentrated (0.5–1.0), both loans and restocking were more often perceived as “more common” by non-diversified households with high Herfindahl values, consistent with the positive linear effects in S1 and S3. Thus, the results on perceived IHE change paint a consistent picture with the previous results of participation: the least-diversified and most livestock-dependent households are mostly likely to use IHE and most likely to perceive that its use has increased over time.

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression models of perception of IHE trends (with odds ratios)

| Predictor | Loans |

Restocking |

Gifts |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As Common | More Common | As Common | More Common | As Common | More Common | |

| Model specification 1 | ||||||

| Household Head Measures | ||||||

| Age | 0.95 | 1.16* | 1.12† | 1.11 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

| Age (sq) | 1.00 | 1.00† | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Church (0/1) | 0.92 | 1.26 | 2.12* | 1.48 | 1.19 | 2.50* |

| Education (0/1) | 0.73 | 3.81*** | 1.50 | 3.29** | 0.92 | 0.95 |

| Household Measures | ||||||

| (AE) | 0.81 | 1.13 | 0.72 | 2.18* | 0.93 | 2.87* |

| Ln (TLU/AE) | 0.94 | 0.47* | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.30 | 0.76 |

| Ln (Land allocation) | 1.05 | 0.50† | 0.96 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.48† |

| Ln (Total income) | 1.14 | 1.55** | 0.97 | 0.83 | 1.56 | 1.27 |

| Adjacent to park (0/1) | 0.43 | 0.20*** | 0.28** | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.26** |

| Diversification Measures | ||||||

| % Income from livestock | 1.50 | 8.57** | 1.62 | 19.58** | 0.58 | 1.27 |

| Nhouseholds | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 |

| Model specification 2 | ||||||

| % Income from livestock | 0.06 | 0.00*** | 4.01 | 0.05 | 2.35 | 0.03 |

| % Income from livestock (sq) | 22.43 | 6.5e+3*** | 0.43 | 194.93 | 0.28 | 88.09 |

| Joint significance test | *** | *** | † | |||

| Model specification 3 | ||||||

| Herfindahl index | 2.42 | 25.04*** | 1.65 | 56.50*** | 0.67 | 11.82* |

| Model specification 4 | ||||||

| Herfindahl index | 0.12 | 0.00 | 6.63 | 1.47 | 67.53 | 0.10 |

| Herfindahl index (sq) | 13.47 | 38970.0 | 0.33 | 14.27 | 0.03 | 31.31 |

| significance test | *** | *** | ns | |||

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Figure 3.

Predicted probabilities of perceiving inter-household exchange as as common or as more common in 2009/2010 compared to 2002/2003 by type (loans and restocking) and measure of livelihood diversification (i.e., Herfindahl index) with mean values of the other predictors.

6. DISCUSSION

The qualitative results of this study provide evidence that: (1) IHE, in the forms of lending, restocking, and gift giving, are used by Maasai households to spread risk, respond to shocks, create and strengthen social networks, support herd and family development (RQ1); and (2) the ways in which households are using IHE are evolving to incorporate new opportunities associated with agriculture and education (RQ1). These findings, also elucidate a set of exchange mechanisms (IHE) that have been under-examined in the ethnographic literature on the Maasai (Aktipis et al., 2011).

In several distinguishable ways, IHE have been central to households’ strategies to insure themselves against catastrophic loss (i.e., restocking), to manage smaller problems (i.e., loans and gifts), and to promote marriage and family development through important inter-generational relationships (i.e., gifts)14. Furthermore, the centrality and versatility of these mechanisms as tools to facilitate social and economic endeavors is exemplified by ongoing adaptations in their use. For example, the incorporation of agricultural products in IHE, which followed immediately after the adoption of agriculture, according to interview respondents, helps to mitigate the risks associated with rain-fed agriculture in an area characterized by high rainfall variability. Unable to move their farms to where the rain falls as they do with livestock, households move harvests, through exchange networks, to where rainfall was limited by transferring surplus harvest to households with low harvests. Similar innovations are evident in the growing use of restocking and loans to support educational opportunities. And yet, despite these innovations, the use of IHE is reported to be on the decline throughout the study area.

The quantitative results of this study provide strong evidence that both the incidence of and perceived trends in IHE are significantly negatively associated with LD at the household level. Indeed, model specifications using two separate measures of LD (i.e., percent of income from livestock and a Herfindahl index) communicate a similar story. Only in the case of restocking do these two measures offer different stories (S2 indicates positive relationship between diversification and restocking).

As noted above, other predictors, specifically age, education, family size, and land allocation were consistent across models and point to other factors that shape engagement with IHE. It is not surprising that older heads and those with larger families would be more engaged in traditional IHE. Similarly, it’s not surprising that access to more agricultural land would be associated with less engagement. Conversely, the effect of education on IHE, which does not vary depending on whether the exchange was given or received (see Appendix 1), is less clear and should be investigated further.

Along these lines, future studies of IHE among the Maasai and other pastoralist societies could be improved in multiple ways. First, sampling a larger number of communities would allow a more thorough investigation of contextual effects. Second, gathering quantitative data on positive and negative shocks to the households would improve our understanding of the contexts in which IHE are used. And third, finding ways to reduce reporting bias (especially in the case of receiving loans), perhaps through ethnographic approaches to estimate under-reporting.

Despite the limitations noted, our qualitative and quantitative findings, taken together, offer strong support for the hypothesis that LD and IHE are inversely related (H1). This relationship was noted in several group interviews with community members, but was elaborated most clearly during an interview about restocking on July 22, 2010. At one point in the interview, the first author asked the question “Is restocking different now from what it was in the past, and if so, how?” The group asserted that there have been no changes in the mechanics of restocking, but that in the past it was used more frequently. In the past, they noted, people were poor and they were depending exclusively on livestock. Today, they said, people have more options. People are engaged in farming, or in wage-labor. A household that has lost many animals, they described, might have farm proceeds to support themselves – so there is no need for restocking.

Ultimately these findings outline a story of adaptation wherein a traditional system of exchange is, at once, evolving and declining. While the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes a more robust examination of change, descriptions from group interviews and data on perceptions from the household survey tell a consistent story of IHE decline. This story of decline, along with the inverse relationship between IHE and LD found here, is well aligned with studies that have detailed the rise in LD among the Maasai in recent decades (Coast, 2002; Homewood et al., 2009; McCabe, 2003; McCabe et al., 2010). Furthermore, these findings add to the literature on the determinants of social networks of exchange in agrarian societies and respond to calls for more research on the social context in which exchanges are used (Cox & Fafchamps, 2007).

The transition from one form of risk management to another holds several implications for the growth, development, and resilience of households and communities. The trend towards LD and individualization in pastoralist societies can be see an effort to protect the livestock economy (McCabe et al., 2010), secure land tenure (Baird et al., 2009), and expand incomes for the purpose of engaging more with the cash economy (Little, 2003). Furthermore, this trend may reduce certain risks, and add others. Diversified households may be more able to manage high incidence / low severity shocks (i.e., illness, single year droughts, etc.), but less well prepared to manage low incidence / high severity shocks (i.e., multiyear- droughts, expansion of park boundaries, etc.). Similarly, where community cohesion is reduced by disengagement in IHE, the ability to mobilize and act collectively in the face of community-level shocks may be reduced as well. This may be especially germane in the case of societies that have traditionally managed commonly held resources – and societies that face repeated external shocks from markets (Priebe et al., 2010), climate-related events (McSweeney & Coomes, 2011) and/or protected areas (Baird & Leslie, 2013). In other words, it may be that improved household development and resilience to small shocks in the short term is being paid for by reduced household and community resilience to larger shocks in the longer term. This calls into question the mutability of these changes.

One debate in the literature on LD among pastoralists is whether LD is cyclical. Arguing that it is, Little et al. (2001) suggested that LD is linked to individual life histories and cycles of family development. Others have argued that process of LD among pastoralists is best understood as linear and permanent (Homewood et al., 2009; McCabe, 2003; McCabe et al., 2010). Our sense, which is based on arguments from these studies as well as extensive fieldwork in the study area, is that LD is indeed unidirectional. So - if LD is linear and negatively correlated with IHE, what new questions do these findings raise regarding the structure and function of social networks more broadly?

(a). Social network transition

The findings presented here, taken alongside the literature on LD among East African pastoralists described above, provide some support for the hypothesis that lower levels of IHE represent a new normal – a watershed in this social network of exchange – and that increased livelihood diversification and reduced IHE are part of the process of transition from an old regime to a new one. Conceptually, this argument proceeds in three basic steps: (1) households diversify; (2) households change the ways they use a social network; and (3) households reduce their engagement with their traditional social network. Prior to the transition, households are characterized by low levels of LD and high levels of IHE. Following the transition, however, this profile is inverted with households exhibiting higher levels of LD and lower levels of IHE. This hypothesis focuses on the network’s density, not its structure, and raises further questions.

What can be the implications for a social/ecological system associated with a social network transition of this nature? There are few studies in the literatures on social ecological systems, livelihoods, or pastoralism that offer insights into this question. Robert Putnam’s book, Bowling Alone (2000), however, on the evolution (and erosion) of community in the U.S. during the twentieth century, draws on numerous studies of social networks and raises several important issues germane to this study. Here we will briefly focus on two: (1) the distinction between bridging and bonding social capital; and (2) the capacity for collective action.

A commonly held notion in the literature on social capital is that social networks confer social capital on their members (Adger, 2003; Pretty, 2003). It follows, therefore, that different types of networks, or connections within a network, offer different types of capital. “Bonding” social capital is a form of capital conferred by network connections that are focused inward within a society or group of people, whereas “bridging” social capital is conferred through connections that are directed outward. Putnam (2000), who credited Gittell and Vidal (1998) with the earliest use of these labels, described bonding and bridging in the following way:

Some forms of social capital are, by choice or necessity, inward looking and tend to reinforce exclusive identities and homogenous groups… Other networks are outward looking and encompass people across diverse social cleavages… Bonding social capital is good for undergirding specific reciprocity and mobilizing solidarity. Dense networks in ethnic enclaves, for example, provide crucial social and psychological support for less fortunate members of the community, while furnishing start-up financing, markets, and reliable labor for local entrepreneurs. Bridging networks, by contrast, are better for linkage to external assets and information diffusion… Bonding capital is, as Xavier de Souza Briggs (1998) puts it, good for ‘getting by,’ but bridging social capital is crucial for ‘getting ahead.’” (2000, 22–23).

Given this distinction, it can be argued that the Maasai institutions of lending, restocking, and gift giving (i.e., IHE) described in this study represent bonding connections between households. Findings from group interviews that IHE are reciprocal and meant to promote solidarity within and across age-sets, and support less fortunate members of the community support the notion that connections are bonding connections. Furthermore, data from our structured survey show that Maasai households conduct IHE almost entirely with other Maasai households (for each transaction recorded, information was collected on the ethnic group of the other party) which serves to create an exclusive, dense network that is inwardly focused.

Framed in terms of bonding connections, the trend towards fewer IHE should be investigated. For example, what are the implications of fewer bonding exchanges? One hypothesis is that reduction in bonding connections, which are part of the glue that holds close-knit communities together, would yield greater household independence and, correspondingly, reduced capacity within the community to act collectively. Like other pastoralist and agro-pastoralists, the Maasai have traditionally managed risk collectively and avoided collective action dilemmas, like the tragedy of the commons (Hardin, 1968), through strong institutions including the age-set system, clan membership, and other social networks founded on exchange and reciprocity (Fratkin & Mearns, 2003; McCabe, 1990a). Together, these institutions promote an atmosphere of trust and interdependency within communities that is central to collective action. It follows, therefore that as these institutions diminish, so too will communities’ capacities to avoid free-rider problems and associated negative outcomes (Ostrom, 1990), including land conversion and degradation – which can introduce risk at multiple scales.

An alternative, but not necessarily mutually exclusive, hypothesis is that a reduction in the number of IHE frees up, or releases, material resources (i.e., household resources that would otherwise have been extended as loans, restocking, or gifts) for use in other types of exchanges and/or connections; especially bridging connections with individuals or groups outside the community. While this study has focused on changes in traditional bonding networks, and therefore cannot address changes in bridging connections at the household level, there are reasons to suspect that bridging trends are becoming more common. Other studies from this area, show that several communities have begun actively recruiting financial resources from external international organizations, in some cases leveraging their close proximity to TNP to encourage tourism and conservation agencies to build education and water infrastructure in the area (Baird, 2014). It’s unclear to what extent households themselves are engaging in bridging behavior. However, observed increases in school construction and school enrollment in the study area suggest, along with evidence of livelihood diversification, that local households are increasingly cultivating new forms of human capital (i.e., education and economic skills) that would facilitate growing integration with external individuals, institutions, and organizations (Little et al., 2009).

(b). Household demography and land use

A final consideration that we will address briefly here is that, given the numerous and complex ways in which IHE are integrated into marriage and household growth, herd development, and the persistence of agriculture, a change in IHE may contribute to dramatic long-term changes in household and community demography, social organization, and land use.

While many studies have linked demographic, social, and land use change to changing livelihoods and integration in the market economy (Caldwell, 1976; Lambin et al., 2001; Thornton & Fricke, 1987), few have focused on the role of exchange networks in demographic shifts. Studies of Maasai demography are themselves scarce (Coast, 2001, 2006). However, circumstances associated with changing use of IHE, which include the waning use of daughters in reciprocal exchanges, the growing use of exchanges to support education, reduced access to loans to address problems, and the incorporation of agriculture into exchange mechanisms may ultimately contribute in important ways to changes in nuptiality and total fertility, increased school enrollment (and a corresponding reduction in the pool of available labor), wage labor and migration, and land conversion to agriculture, respectively.

Certainly, the decline of IHE identified here raises concerns about households’ and communities’ abilities to confront future challenges including perennial struggles such as drought and disease (Aktipis et al., 2011; McCabe, 1987). But it also raises concerns about how Maasai will confront new challenges associated with climate change, a growing global concern for environmental conservation, and their own increasing engagement with a rapidly developing world. It may be that the persistence of social networks of exchange, albeit at a level reduced from earlier times, combined with the benefits of individual livelihood diversification and the development of bridging relationships allows for the flexibility to meet these challenges.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Data collection for this study was supported by a Fulbright-Hays Fellowship through the U.S. Department of Education, a Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant (DDRI) through the National Science Foundation, and a research grant through the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We thank Gabriel Ole Saitoti and Isaya Rumas for their dutiful assistance in the field as well as Terry McCabe for his accommodation and guidance. Helpful comments on a previous draft of this manuscript were provided by Paul Leslie, Martin Doyle, Peter White, and Tom Whitmore. In addition, reviewers of the manuscript made several useful suggestions.

Footnotes

Material goods maybe livestock, food, clothing, tools, etc.

The Maasai age-set system organizes initiated men into 14 to 15 year cohorts and provides structure for the progression of men from warrior-hood through junior and senior elder statuses over the course of their lives. Men within a cohort move through these positions together and individuals will remain apart of their cohort for life.