Abstract

Objective.

Healthcare professionals who work in palliative care units face stressful life events on a daily basis, most notably death. For this reason, these professionals must be equipped with the necessary protective resources to help them cope with professional and personal burnout. Despite the well-recognized importance of the construct “meaning of work,” the role of this construct and its relationship with other variables is not well-understood. Our objective is to develop and evaluate a model that examines the mediating role of the meaning of work in a multidisciplinary group of palliative care professionals. Using this model, we sought to assess the relationships between meaning of work, perceived stress, personal protective factors (optimism, self-esteem, life satisfaction, personal growth, subjective vitality), and sociodemographic variables.

Method.

Professionals (n = 189) from a wide range of disciplines (physicians, psychologists, nurses, social workers, nursing assistants, physical therapists, and chaplains) working in palliative care units at hospitals in Madrid and the Balearic Islands were recruited. Sociodemographic variables were collected and recorded. The following questionnaires were administered: Meaning of Work Questionnaire, Perceived Stress Questionnaire, Life Orientation Test-Revised, Satisfaction with Life Scale, Subjective Vitality Scale, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and the Personal Growth Scale.

Result.

The explanatory value of the model was high, explaining 49.5% of the variance of life satisfaction, 43% of subjective vitality, and 36% of personal growth. The main findings of this study were as follow: (1) meaning of work and perceived stress were negatively correlated; (2) optimism and self-esteem mediated the effect of stress on the meaning attached to work among palliative care professionals; (3) the meaning of work mediated the effect of stress on subjective vitality, personal growth, and life satisfaction; and (4) vitality and personal growth directly influenced life satisfaction.

Significance of results.

The proposed model showed a high explanatory value for the meaning professionals give to their work and also for perceived stress, personal protective factors, and sociodemographic variables. Our findings could have highly relevant practical implications for designing programs to promote the psychological well-being of healthcare professionals.

Keywords: Meaning of work, Optimism, Palliative care, Perceived stress, Personal growth, Professionals, Satisfaction with life, Self-esteem, Spirituality, Vitality

Introduction

Healthcare professionals are exposed to numerous work-related stressors (Eckersley & Taylor, 2016), and certain medical specialties such as palliative care can be particularly stressful because of the emotional demands caused by daily contact with human suffering during the dying process (Aguilar & Huertas, 2015; Applebaum et al., 2015). Moreover, in the end-of-life context, these professionals are engaged in complex and highly sensitive life issues, which can potentially have an immense psychological impact (Back et al., 2015; Boston et al., 2011; Chittenden & Ritchie, 2011).

The most common stressors of palliative care professionals are lack of time, understaffing, complex and sometimes difficult relationships with the patient and their families, and the short time frame of the dying process. Given the numerous potential stressors, it is essential that these professionals be equipped with personal resources to successfully cope with stressful events. Such resources can be defined as general characteristics of a personal, interpersonal, or external nature, whose function is to regulate stress and stressful events. Personal resources can play a crucial role in minimizing stressors and preventing chronic stress, as well as promoting effective strategies for proper stress management (Milaniak et al., 2016). According to Milaniak et al. (2016), personal resources can be classified into two broad categories: external (i.e., physical, biological, and/or social factors) and internal (i.e., spiritual or psychological factors). Previous research has shown that certain personal resources, such as optimism and self-esteem, can influence an individual’s competency in handling emotionally stressful life situations, as well as in developing resistance to negative consequences (physical and psychological) resulting from stressful events (Jerusalem, 1993; Milaniak et al., 2016).

An internal resource that has proven to have an important role in palliative care is the meaning of work, a construct that has been defined in many different ways. Frankl (1969) postulated that the meaning of work was associated with the purpose and reason for living, as well as vocation. Other authors, such as Steger et al. (2012), have expanded the definition beyond just “everything that work means for individuals” (i.e., meaning) to include also “significant and positive in valence.” Beyond these conceptual variations, most research studies agree that meaning in work is a protective factor against stress.

According to Tei et al. (2015), health professionals who have a greater sense of the meaning of their work are able to recognize its importance, thus changing how they interpret certain critical situations. Exposure to patient distress may induce less stress in healthcare professionals who find a greater meaning in such events (for example, if they believe they are alleviating the suffering of their patients). Other authors (Arnoux-Nicolas et al., 2016; Humphrey et al., 2007) recognize the role of the meaning of work, but they assign it a mediating role between resources (i.e., self-esteem and optimism) and variables resulting from the work itself (i.e., life satisfaction or personal growth).

Despite agreement regarding the importance of the construct “meaning of work,” the role of this construct and its relationship with other variables has not yet been clearly established. In this context, the aim of the present study was to develop and evaluate a model that examines the mediating role of the meaning of work among a multidisciplinary group of palliative care professionals in Spain.

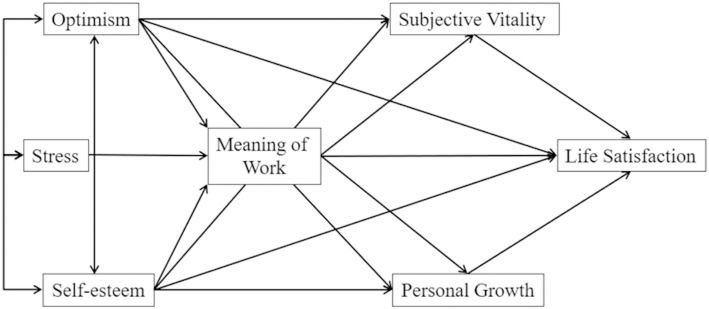

In the proposed model (Figure 1), meaning of work plays a mediating role among stress, personal protective factors (optimism and self-esteem), and outcome variables such as life satisfaction, personal growth, and subjective vitality. Using this model, we aimed to determine (1) if there is a negative association between meaning of work and perceived stress, and (2) whether the meaning of work mediates the influence of optimism and self-esteem on life satisfaction, personal growth, and subjective vitality. An additional aim was to determine whether there are differences in the degree of optimism, self-esteem, satisfaction with life, subjective vitality, personal growth, perceived stress, and meaning of work as a function of the sociodemographic variables of this group of professionals.

Fig. 1.

Path diagram of the meaning of work model.

Although previous studies involving palliative care professionals have assessed variables such as perceived burnout or coping strategies (Aguilar & Huertas, 2015), little research has been conducted to investigate the effects of stress and the moderating role of personal resources on these healthcare professionals. In this context, we hypothesized that palliative care professionals who give greater meaning to their work would perceive less stress.

Method

Participants

One hundred and eighty-nine palliative care professionals from a wide range of occupational categories in Spain voluntarily agreed to participate in this prospective survey. Nurses accounted for 40.5% of the sample, followed by nursing assistants (31.1%), and doctors (14.2%). Of the remaining participants, 7.4% were psychologists, 4.2% social workers, and 2.6% “other professionals” (physiotherapists and chaplains.) The overall sample consisted of 36 men and 153 women. The mean age was 42.2 years (range, 18–73). Of the 189 participants, 73% were in a stable relationship (partner or spouse) and 62.6% had children (compared with 37.4% without any children). Most of the professionals (78.4%) had ≥10 years of experience in palliative care and 60.7% had held the same job for the entire time. Most participants (84.7%) worked in hospitals 30–45 hours per week and 71.6% had permanent contracts versus 28.4% with temporary contracts.

Regarding the role of beliefs, 52.1% reporting having spiritual beliefs and 39.7% religious beliefs. Table 1 provides detailed information on the sample distribution by professional category and Table 2 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Distribution of the sample by professional categories (%)

| Professional category | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Nurses | 77 (40.5) |

| Nursing assistants | 59 (31.1) |

| Physicians | 27 (14.2) |

| Psychologists | 14 (7.4) |

| Social workers | 8 (4.2) |

| Others* | 4 (2.6) |

| Total | 189 (100) |

Chaplains and physiotherapists.

Table 2.

Distribution of the sample by sociodemographic variables (%)

| Variable | Data |

|---|---|

| Gender | 153 (81.1) vs 36 (18.9) |

| Women vs men | |

| Age, years (range) | 42.17 (18–73) |

| Civil status | 140 (73.7) vs 49 (26.3) |

| Partner vs no partner | |

| Number of children | 70 (37.4) |

| 0 | 42 (22.1) |

| 1 | 58 (30.5) |

| 2 | 19 (10) |

| 3 | |

| Total professional experience, years | 43 (21.7) |

| ≤5 | 47 (15.1) |

| 5–10 | 99 (63.2) |

| >10 | |

| Experience in palliative care, years | 86 (45.3) |

| ≤ 5 | 36 (19.2) |

| 5–10 | 67 (35.5) |

| >10 | |

| Experience in current work unit, years | 129 (41.5) |

| ≤5 | 16 (19.2) |

| 5–10 | 44 (39.3) |

| >10 | |

| Number of hours per week | 15 (7.9) |

| ≤30 | 160 (84.7) |

| 30–45 | 14 (7.3) |

| >46 | |

| Area of care | 139 (73.5) vs 50 (26.5) |

| Hospital vs community | |

| Type of contract | 135 (71.6) vs 54 (28.4) |

| Permanent vs temporary | |

| Religious vs spiritual practice | 99 (52.1) vs 75 (39.7) |

All data are N (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Procedure

The principal investigator first contacted the head of the palliative care unit and the medical director at each participating center. After explaining the objectives of the study, the investigator asked for volunteers. All data were collected anonymously. The research study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at all participating institutions.

After obtaining the center’s agreement to participate, the researcher scheduled a session at the center to present the study and to administer the self-report instruments to the healthcare professionals who attended the session, which took place during regular working hours.

The participants completed the battery of self-report questionnaires (described in the following section) in the presence of the researcher, who remained in the room to answer any questions that might arise. The final sample consisted of all the professionals (n = 189) who met the study inclusion criteria, which were as follows: (1) employment in a palliative care unit and (2) forming part of one of the following professional categories: doctor, psychologist, nurse, nurse practitioner, social worker, physiotherapist, or chaplain.

Instruments

Sociodemographic variables

The following sociodemographic variables were evaluated: age, sex, marital status, cohabitation status (i.e., with or without a partner), and number of children. The professionals were grouped into the following categories: doctors, nurses and nursing assistants, psychologists, social workers, and “other professionals.” Information about the workplace (hospital/community), type of contract (indefinite/temporary), and the total number of years of work experience was also recorded. In the palliative care setting, we also assessed the number of hours worked per week and whether the professional had any religious or spiritual beliefs/practices.

Meaning of Work Questionnaire

Meaning of work was measured using a ten-item version of the Meaning of Work Questionnaire with a Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

The original version of the questionnaire had 19 items (Villa George, 2013). However, the first exploratory factor analysis performed to evaluate this scale showed that two dimensions explained 51.7% of the total variance; a confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the adequacy of a 10-item unifactorial model (comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.96; non-normed fit index [NNFI] = 0.94; root mean residual = 0.03; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.05).

On the 10-item Meaning of Work Questionnaire, total scores ranged from 5 (low meaning) to 50 (high meaning), with higher values indicating greater meaning of work. Meaning of work has long been associated with positive variables such as organizational commitment (Chalofsky & Krishna, 2009), psychological wellbeing (Winefield & Tiggemann, 1990), and work motivation (Westaby et al., 2005).

Perceived Stress Questionnaire

Daily stress was measured by the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ). This instrument consists of 30 reactive items with four response options (1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = almost always). Respondents report their perception of recent stress during the past month. For the current study, we modified the original tool developed by Levenstein et al. (1993), which was designed for use in a wide variety of situations to allow people to subjectively describe their experiences. The PSQ can be applied to men and women of any age or socioeconomic level. The PSQ was developed to assess stressful situations and the perception of stress reactions as a cognitive whole and, to an extent, at an emotional level. This questionnaire allows comparisons, there is no cutoff point, and it is an index (scored from 0 to 1), which is defined as: PSQ = total 30/90. The higher the index value, the higher the level of perceived stress.

The PSQ has good psychometric characteristics and is highly correlated with several different scales, including Cohen’s Stress Perception Scale, the State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory, and the Depression Scale. The instrument also has external validity, which was demonstrated in the prospective study by Levenstein et al. (1993), who used the PSQ to predict adverse health outcomes. The PSQ is one of the most commonly used instruments to assess perceived stress, and research has shown that it is a better measure of stress than other available instruments (Moretti & Medrano, 2014).

Dispositional Optimism Questionnaire

To measure dispositional optimism (predisposition to expectations of positive or negative results), we used the Spanish version of the Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) developed by Otero et al. (1998). The LOT-R consists of six items (plus four distractors). The wording of the questions that assess optimism and pessimism are phrased, respectively, positively and negatively, thus yielding one score for optimism and another for pessimism. By reversing the scores of the three negatively worded items, a general dispositional optimism score is obtained. The LOT-R is a short scale that is easy to administer. Higher values on this scale indicate greater optimism. Ferrando et al. (2002) evaluated the external validity of the LOT-R using three constructs: (1) negative affectivity, (2) perceived stress, and (3) neuroticism. Validity coefficients were relatively high and in the expected direction in all cases. A two-factor structure was obtained that showed a better fit (chi-square = 5.66; degree of freedom [df] = 4). The bifactorial model had a better fit than the unifactorial model (chi-square = 32.67; df = 1; RMSEA = 0.041; NNFI = 0.96).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

Self-esteem was assessed with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES). The RSES is a Likert-type scale that is widely used to measure overall self-esteem. The scale contains 10 items to evaluate the respondent’s respect for, and acceptance of, himself or herself. The Spanish version of the scale (Martín-Albo et al., 2007) has shown adequate psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.85 and 0.88 and a test-retest correlation of 0.84. The unifactorial structure was confirmed using confirmatory factor analysis showing a good fit for this model (chi-square = 37.66; Bollen’s Incremental Fit Index [IFI] = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.03).

Satisfaction with Life Scale

Satisfaction with life was evaluated through the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), developed by Diener et al. (1985) in the United States. The Spanish version was translated and validated by Atienza et al. (2000). The five-item SWLS is a measure of the concept of personal life satisfaction considered in its entirety, not as a specific aspect.

On the SWLS, subjects are asked to indicate their level of agreement with each item on the scale using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). This scale is short and easy to administer. Scores can range from 5 (low satisfaction) to 35 (high satisfaction), with the highest values indicating greater life satisfaction.

The psychometric analyses carried out by Atienza et al. (2000) found a unifactorial structure that explained 53.7% of the variance. The Cronbach’s alpha (0.84) indicates an adequate internal consistency. The model fit was verified using confirmatory factor analysis (chi-square = 14.12; GFI = 0.98; NNFI = 0.99).

Subjective Vitality Scale

Vitality was evaluated using the Spanish version (Balaguer et al., 2005) of the original Subjective Vitality Scale (Ryan & Frederick, 1997). The seven-item Subjective Vitality Scale measures overall subjective feelings of liveliness, enthusiasm, and energy. Responses are given on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not true) to 7 (true), with higher scores indicating greater vitality. The scale has been validated, with adequate internal consistency indices (α = 0.80), and confirmatory factor analyses supporting a unifactorial structure by eliminating item 2 (chi-square = 19.44; GFI = 0,98; Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index [NFI] = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.06) (Bostic et al., 2000). Similar results were obtained in the Portuguese version (Moutão et al., 2013), where confirmatory analyses confirmed the unifactorial structure (chi-square = 34.93; NNFI = 0.961; CFI = 0.970; RMSEA = 0.074).

Personal Growth Scale

Personal growth was evaluated using the Personal Growth subscale. The Personal Growth Scale forms part of the Psychological Well-Being Scale (Ryff & Singer, 2006), which has been adapted into Spanish (Van Dierendonck et al., 2006). This scale consists of 29 items distributed into six subscales: self-acceptance, positive relations, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. In the present study, we used the Personal Growth Scale subscale only, which contains four items that measure the optimal functioning perceived by the person and his or her commitment to developing the potential to continue growing as a person to maximize their capabilities. Responses are graded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). The total score ranges between 6 and 24.

The Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scale (Van Dierendonck et al., 2006) showed an adequate internal consistency on all dimensions. In addition, confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated the adequacy of the model (chi-square = 615.76; NNFI = 0.94; CFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.04).

Statistical analysis

For all analyses, we followed the steps proposed by Batista and Coenders (2000). First, the model in Figure 1 was specified in the Analysis of Moment Structures, v. 17.0, program. We then proceeded with the estimation of the model using the maximum probability method. Finally, the fit of the proposed model was evaluated using multiple adjustment indicators: (1) the chi-squared statistic; (2) the Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index (CFI); (3) the goodness of fit index (GFI); and (4) the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). To interpret these indices, we used the critical values recommended previously in other studies (Byrne, 2001; Medrano & Muñoz-Navarro, 2017). Specifically, values >.90 and .95 for the GFI and CFI were considered benchmarks for acceptable and good fit, respectively; and RMSEA values of <.08 and .06 were benchmarks for acceptable and good fit, respectively.

Results

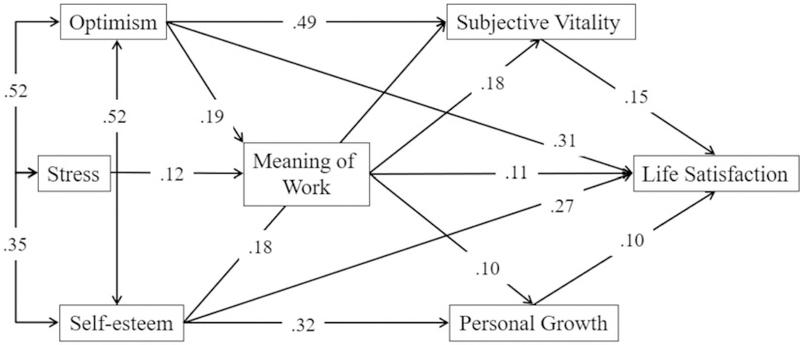

Table 3 shows that the indices suggest a good fit, although the parsimony index (RMSEA) is higher than recommended. In terms of the statistical significance of each path on the model, the weight of self-esteem on meaning of work is not statistically significant. There were also no statistically significant results between optimism and personal growth. Removing these parameters improves the model parsimony (M2). Figure 2 shows the final model with the standardized beta values for each path.

Table 3.

Model fit indices of the model

| Chi-square | df | CFI | GFI | RMSEA | Chi-square differential | ΔCFI | ΔGFI | ΔRMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–10 M 1 | 24.33* | 4 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.16 | ||||

| M 2 | 24.77* | 5 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.14 | ||||

| Difference between M1 and M2 | 0.54 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

CFI, comparative fit index; df, degree of freedom; GFI, goodness of fit index; M, model; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

p < .05.

Fig. 2.

Standardized path diagram of the meaning of work model (M2)

With regard to the magnitude of the total effects, self-esteem (total β = .32) and optimism (total β = .44) had the greatest effect on life satisfaction. Meaning of work contributed both directly and indirectly to life satisfaction through personal growth and subjective vitality. Our findings confirm the significant total effect that meaning of work has on life satisfaction (total β = .15). Interestingly, the direct effect of stress on the meaning of the work was low (β total = .12). The model had a high explanatory value, explaining 49.5% of the variance of life satisfaction, 43% of subjective vitality, and 36% of personal growth. This finding indicates that the model possesses an excellent explanatory power overall.

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the interaction between meaning of work and the level of perceived stress among healthcare professionals in a palliative care setting. We also assessed the role of protective factors. The findings presented here suggest that improving the meaning of work can have a protective effect against stress, thereby improving the quality of care provided by palliative care professionals.

The proposed model had a high explanatory value for our findings with regard to the meaning of work among these professionals, as well as for the perceived stress and the other variables. In line with previous studies, we found significant positive correlation between life satisfaction, personal growth, and vitality. In other words, improvement in one of these three variables could also improve the others, as evidenced in the results of studies that have successfully applied an intervention.

We also found a positive, bidirectional association between optimism and self-esteem, both of which seem to help palliative care professionals mitigate the potential negative effect of daily stress on the meaning they attribute to their work. In short, it appears that caregivers who are more optimistic and have sufficient self-esteem may feel more satisfied, both in their work and in their personal lives.

Consistent with previous reports (Sinclair, 2011), we found that palliative care professionals feel more alive, empathic, sensitive, and spiritual-oriented because of their repeated exposure to death; even these experiences can provide certain insight into the nature of death that may benefit individuals facing the end of life (Shanafelt et al., 2005). However, much less is known about how these professionals incorporate these experiences into their personal lives and clinical practices (Sinclair, 2011). A novel finding of our research is that the variables “vitality” and “personal growth” are associated with a large positive effect on life satisfaction, which could be explained by the psychological maturity that is acquired through taking care of other humans, together with the “transformational learning” of work in an end-of-life setting (Chan et al., 2015).

Many of our findings are in line with previous research, particularly the finding that the healthcare professionals with the most stress tend to assign less meaning to their work (Olson & Kemper, 2014). Nevertheless, many professionals experience their work with a high degree of commitment and meaning, despite high levels of stress, as other studies have reported (Fillion et al., 2009; Shanafelt, 2009). In this regard, the healthcare professionals in our study tend to see their professional activity not as a burden, but as a challenge, as well as a path for self-realization and personal growth, regardless of their individual sociodemographic characteristics.

Our findings indicate that healthcare professionals tend to handle anguish by developing useful life attitudes and that they conceive their work to be a privilege. These findings were true for the whole sample, regardless of the professional category, workplace setting, or other sociodemographic variables. This is a highly relevant finding because it confirms, once again, the importance of cultivating and maintaining a positive attitude toward life until the end of our days (Frankl, 1969). Such an attitude allows us to grow, not only at work, but also in our personal lives (Breitbart, 2017). This study further deepens our understanding of the value of psychological resources as an essential tool to manage the effect of stress. These psychological resources may help to optimize the work professional life in this setting and in others.

In the field of occupational health, most studies group healthcare professionals into professional categories (e.g., nurses, doctors) in order to design interventions targeted at the largest groups. We believe that the current study represents an important advance in this line of research, for several reasons. First, the study was based on theoretical models that emphasize the importance of using a range of personal resources to cope with stress, an approach that differs substantially from the numerous studies centered exclusively on the role of stress in palliative care. Second, we have evaluated and established the important role of several variables (i.e., meaning of work, satisfaction with life, optimism, vitality, self-esteem, personal growth, and spirituality), most of which have received little attention in previous studies carried out in this setting.

We believe that the novel findings presented here support the start of a new, promising, and necessary line of research in the field of occupational health in palliative care; however, additional qualitative, intercultural, and longitudinal studies are needed to further support the findings presented here. Our findings may have important practical implications for the development and refinement of prevention programs to improve workplace health among palliative care professionals. For example, one implication is that managers have a key responsibility—beyond proposals for continuous training—to contribute to a more humane work environment through concrete actions. To do so, however, requires a deep knowledge of the resources available to optimize the working conditions of all the professionals who care for us and our children when the time comes.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is that we have identified the importance of personal variables that have either not been investigated previously or have received little attention in the context of palliative care professionals. In addition, we have selected and used the most suitable tools to assess these variables. We believe this study provides a highly relevant contribution to a novel line of research, which merits more development to determine the care that should be provided to caregivers in a high demand field such as palliative care.

One surprising result of this study is how little stress the meaning these professionals give to their work. In general, previous studies indicate that chronic stress is associated with increased levels of cynicism (Castellano et al., 2013; Llorens et al., 2005), which is associated with a lower meaning of work. The use of a general stress scale rather than an instrument specifically designed to measure stress in the work context may have affected the magnitude of the relationships observed. For this reason, future studies should include measures of work stress to more accurately examine the relationship between these variables. Other limitations of this study are related to methodological aspects. Although our sample was large and varied, women made up >80% of the sample (81.1% vs. 18.9%) and, moreover, >70% of the participants were nurses (40.5%) or nursing assistants (31.1%). Given the minimal differences in demographic variables among the participating, however, our findings are probably applicable to most palliative care professionals. Another methodological limitation is the cross-sectional design, which does not allow us to draw causal interpretations, but only allows us to report on associations between variables or trends. For this reason, we must be cautious when suggesting practical implications.

Conclusions

The results of this study provide further support for the theories and models proposed in the published literature. The model presented here has an excellent explanatory power to describe the interaction between the meaning of work, perceived stress, personal protective factors, and sociodemographic variables among this group of palliative care professionals. The personal variables evaluated in this study—which included life satisfaction, optimism, self-esteem, vitality, personal growth, and meaning of work—allow professionals to better manage the balance between stress, demands, and resources in their personal and professional lives.

The key findings and conclusions of this study are as follows: (1) optimism and self-esteem moderate the effect of stress on the meaning that palliative care professionals give to work; (2) meaning of work mediates the effect of stress on subjective vitality, personal growth, and life satisfaction; and (3) vitality and personal growth seem to exert a direct influence on life satisfaction.

To conclude, achieving life satisfaction can be an arduous and complex task; however, life satisfaction appears to be a crucial component of professional development. Consequently, healthcare professionals must strive to assess, above all, their relationship with themselves and with others to increase their life satisfaction. To optimize vitality, it is essential to identify the things that give meaning to our lives and to prioritize those aspects. Finally, this assessment needs to be repeated periodically—as often as necessary—until it has been fully incorporated into our lives. This is spirituality. As we age, we may feel that we have not lived coherently with our values, projects, and dreams. Without a doubt, this would be a sad ending. During our professional careers, we work very hard to help our patients understand the importance of living in accordance with our values. We owe ourselves the same respect and care.

Acknowledgments.

To all the palliative care professionals of the Community of Madrid and the Balearic Islands; for their vocation and their motivation to participate in this study.

References

- Aguilar CA and Huertas LA (2015) Burnout y afrontamiento en los profesionales de salud en una unidad de cuidados paliativos oncológicos. Psicología y Salud 25(1), 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum AJ, Kulikowski JR, Breitbart W (2015) Meaning‐Centered Psychotherapy for Cancer Caregivers (MCP‐C): Rationale and overview. Palliative and Supportive Care 13, 1631–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnoux-Nicolas C, Sovet L, Lhotellier L, et al. (2016) Perceived work conditions and turnover intentions: The mediating role of meaning of work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atienza F, Pons D, Balaguer I, et al. (2000). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida en adolescentes. Psicothema 12, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Back A, Rushton C, Kaszniak A, et al. (2015) Why are we doing this? Journal of Palliative Medicine 18, 26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer I, Castillo I, García-Merita M, et al. (2005) Implications of structured extracurricular activities on adolescent’s well-being and risk behaviours: Motivational mechanisms. Oral presentation at the 9th European Congress of Psychology; Granada, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Batista JM and Coenders G (2000) Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales. Madrid: La Muralla. [Google Scholar]

- Bostic TJ, Rubio DM, Hood M (2000) A validation of the subjective vitality scale using structural equation modeling. Social Indicators Research 52, 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Boston P, Bruce A, Schreiber R (2011) Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: An integrated literature review. Journal Pain and Symptom Management 41(3), 604–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart W (2017) Meaning-centered psychotherapy in the cancer setting. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2001) Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. International Journal of Testing 1(1), 55–86. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano E, Cifré E, Spontón C, et al. (2013) Emociones positivas y negativas en la predicción del burnout y engagement en el trabajo. Revista Peruana de Psicología y Trabajo Social 2(1), 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chalofsky N and Krishna V (2009) Meaningfulness, commitment, and engagement: The intersection of a deeper level of intrinsic motivation. Advances in Developing Human Resources 11(2), 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chan WCH, Tin AF, Wong KLY (2015) Coping with existential and emotional challenges: Development and validation of the self-competence in death work scale. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 50(1), 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittenden EH and Ritchie CS (2011) Work-life balancing: challenges and strategies. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14, 870–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons R, Larsen RJ, et al. (1985) The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49, 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckersley G and Taylor C (2016) Do experienced physiotherapists working in palliative care services show resilience to stress, burnout and depression? Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 5 (6), 771–936. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando PJ, Chico E, Tous JM (2002) Propiedades psicométricas del test de optimismo Life Orientation Test. Psicothema 14(3), 673–680. [Google Scholar]

- Fillion L, Duval S, Dumont S, et al. (2009) Impact of a meaning-centered intervention on job satisfaction and on quality of life among palliative care nurses. Psycho-Oncology 18(12), 1300–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE (1969) The will to meaning. New York: New American Library. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey SE, Nahrgang JD, Morgeson FP (2007) Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. Journal of Applied Psychology 92(5), 1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerusalem M (1993) Personal resources, environmental constraints, and adaptational processes: The predictive power of a theoretical stress model. Personality and Individual Differences 14, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, et al. (1993) Development of the perceived stress questionnaire: A new tool for psychosomatic research. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 37(1), 19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorens S, García-Renedo M, Salanova M (2005) Burnout como consecuencia de una crisis de eficacia: un estudio longitudinal en profesores de secundaria. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones 21(1–2). [Google Scholar]

- Medrano LA and Muñoz-Navarro R (2017) Conceptual and practical approach to structural equations modeling. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria 11(1), 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Albo J, Núñiez JL, Navarro J, et al. (2007) The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Translation and validation in university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 10(2), 458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milaniak I, Wilczek E, Ruzycka K, et al. (2016) Role of personal resources in depression and stress in heart transplant recipients. Transplantation Proceedings 48(5), 1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti L and Medrano L (2014) Estructura factorial del cuestionario de estrés percibido en la población universitaria, Evaluar 14(1), 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Moutão J, Alves S, Cid L (2013) Traducción y validación de la Subjective Vitality Scale en una muestra de practicantes de ejercicio portugueses. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicologia 45(2), 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Olson K and Kemper KJ (2014) Factors associated with well-being and confidence in providing compassionate care. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine 19(4), 292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero JM, Luengo A, Romero E, et al. (1998) Psicología de la Personalidad. Manual de prácticas. Barcelona: Ariel Practicum. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R and Frederick C (1997) On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality 65(3), 529–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD and Singer BH (2006) Best news yet on the six-factor model of wellbeing. Social Science Research 35(4), 1103–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt T (2009) Enhancing meaning in work: A prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA 302(12), 1338–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt T, West C, Zhao X, et al. (2005) Relationship between increased personal well-being and enhanced empathy among internal medicine residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20(7), 559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S (2011) Impact of death and dying on the personal lives and practices of palliative and hospice care professionals. Canadian Medical Association Journal 8(2), 180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Dik BJ, Duffy RD (2012) Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment 20 (3), 322–337. [Google Scholar]

- Tei S, Becker C, Sugihara G, et al. (2015) Sense of meaning in work and risk of burnout among medical professionals. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 69(2), 123–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dierendonck D, Abarca A, Díaz D, et al. (2006) Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema 18(3), 572–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa George FI (2013) El Desgaste Profesional en Trabajadores Mexicanos de la Salud: El Papel de las Expectativas Laborales y el Significado del Trabajo In Moreno Jiménez B and Garrosa Hernández E (eds), Salud laboral. Riesgos laborales psicosociales y bienestar laboral. Spain: Pirámide Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Westaby J, Versenyi A, Hausmann R (2005) Intentions to work during terminal illness: An exploratory study of antecedent conditions. Journal of Applied Psychology 90(6), 1297–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winefield AH and Tiggemann M (1990). Employment status and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology 75(4), 455–459. [Google Scholar]