Abstract

Purpose

Despite management, some patients continue to have bothersome lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). We examined characteristics associated with LUTS bother in a prospective cohort.

Materials and Methods

Data were obtained from care-seeking patients with LUTS at six US tertiary-care centers in a one-year prospective, observational cohort study. Participants answered the American Urological Association Symptom Index global urinary bother question at study entry and 12 months later. Multiple linear and logistic regressions were used to identify factors associated with 12-month urinary bother.

Results

Of 756 participants, 121 (16%) had worsened LUTS bother over the study period. Baseline factors associated with more severe bother at 12 months among men included non-white race, hypertension, worse urinary frequency and incontinence, and higher levels of stress (all p<0.05). Among women, more severe bother at baseline, urinary urgency and frequency, and worse physical function were associated with more severe bother at 12 months. Adjusted for other variables, worsened LUTS were more likely among men who were non-white (OR [95% CI]=1.79 [0.95–3.39]) or diabetic (OR=1.68 [0.86–3.26]) and among women with diabetes (OR=1.78 [0.86–3.65]), prior LUTS treatment (OR= 2.59 [1.24–5.40]), or higher levels of depression (OR=1.30 [1.11–1.53]).

Conclusion

Urinary symptom severity at baseline, race, depression, and psychological stress were associated with LUTS bother in a prospective cohort of men and women treated at tertiary-care facilities. These findings may inform the clinical care of patients with bothersome LUTS and direct providers to better prognosticate challenging LUTS cases.

Keywords: symptom persistence, lower urinary tract, multivariate analysis

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) affect a large proportion of the US population, with increasing prevalence with age. 1,2 LUTS patients presenting for medical care and diagnosis are the proverbial “tip of the iceberg”, given that disease burden is underreported.3 LUTS can be bothersome and adversely affect an individual’s quality of life (QOL) and are associated with high personal and societal costs. Management options for LUTS include behavioral modifications, physical therapy, pharmacotherapy, minimally-invasive procedures, and surgery. Although there are guidelines that may help in choosing among available treatments, success rates are variable, and can be hampered by low adherence 4,5. Much remains unknown about the longitudinal trajectory of LUTS, including the characteristics of patient subgroups who continue to report being bothered by symptoms despite receiving treatment.

Given that a substantial percentage of patients being treated for various types of LUTS do not report symptomatic improvement, and may even experience worsening symptoms despite seeking care, it is important to identify the pertinent characteristics of these patients. It could be that patients who are likely to continue to be bothered by symptoms can be prospectively identified and that identification could impact clinical decision-making. We sought to identify characteristics associated with worsening LUTS bother over time among patients seeking care in the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN) observational cohort study. We hypothesized that baseline patient characteristics unrelated to treatment would predict worsening LUTS bother over time.

Materials and Methods

LURN was established in 2012 (www.nih-lurn.org) as a trans-disciplinary research network. It includes six geographically dispersed urology and urogynecology clinical research sites and a data coordinating center (DCC). The development of the network, its objectives, and the conceptual framework has been described previously 6. Patients seeking care for LUTS at these tertiary-care sites were prospectively enrolled into the observational cohort study. This study was approved by the institutional review board at each of the participating centers and the DCC. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

From June 2015 through January 2017, we prospectively enrolled men and women presenting for specialty clinical care for LUTS at a LURN research site. Patients were invited to participate if they reported at least one urinary symptom in the past month using the LUTS Tool; additional study inclusion and exclusion criteria were reported previously 7. Participants who enrolled into this study may or may not have received prior treatment for LUTS.

For each participant, we collected demographic and clinical information at baseline, including body mass index (BMI), smoking and drinking habits, comorbidities, history of urinary tract infection, family history of LUTS, post-void residual (PVR), Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) for women, and digital rectal exam findings for men. Prior LUTS therapeutic information—including non-traditional and non-medicinal therapies—was also collected at baseline. In addition, participants completed the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal (GI) bowel incontinence, diarrhea, constipation, depression, anxiety, physical functioning, and sleep disturbance form, as well as the Genitourinary Pain Index (GUPI), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and the Childhood Traumatic Events Scale 8–11. PROMIS measures T-scores have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10 in the US general population. The minimal clinically important differences (MCID) is 3 to 5 points in T-scores across PROMIS measures.

The LUTS Tool and the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI) were used to capture self-reported urinary symptoms and were collected at baseline and 12-month follow-up visits 12,13. Frequency, post-micturition symptoms, urgency, voiding difficulty, bladder/micturition discomfort, and urinary incontinence (UI) severity scores were created by combining responses to related symptom severity questions and calculating the Euclidean length of the relevant questions as a measure of overall symptom severity 14. Female and male cluster memberships identified in the LURN study using the LUTS Tool and AUA-SI were applied to our cohort of participants15,16.

Definition of Worsening LUTS Bother

Question 8 of the AUA-SI was used as a global assessment of a participant’s bother regarding their urinary condition. Participants were categorized into two groups based on their answers to Question 8 of the AUA-SI at baseline and at 12 months: “If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition just the way it is now, how would you feel about that?”, with responses ranging from 0 (“delighted”) to 6 (“terrible”). Participants were excluded from analysis if they were missing AUA-SI Question 8 at baseline or 12 months or if they did not have sufficient bother at baseline, as defined by responses of 0 (“delighted”) or 1 (“pleased”). Participants with worsening bother, i.e., those whose bother at 12 months was more severe than that at baseline and participants who reported the most severe level of bother (i.e., score 6 [“terrible”]) at both baseline and 12 months were included in the “worsened” group. Participants whose bother stayed the same or improved from baseline to 12 months were included in the “not worsened” group (with the exception of those reporting the most severe level of bother at both time points, i.e., score 6 [“terrible”]).

Statistical Analysis

We identified demographic characteristics, self-reported health measures, and physical exam findings at baseline that we hypothesized would be associated with LUTS bother. Bivariate associations between group membership and patient characteristics at baseline were assessed using chi-squared, Fisher’s exact, or Wilcoxon two-sample tests. Changes in LUTS Tool and AUA-SI scores from baseline to 12 months were calculated within each group and tested using paired t-tests controlling for false discovery rate using the Benjamini and Hochberg linear step-up method 17. Multiple linear regression was used to identify factors associated with bother at 12 months, including baseline bother as an independent variable. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with being in the worsened group. All models were performed separately for women and men. Variable selection was conducted using stepwise selection with entry level at p=0.10 and stay level at p=0.15. Covariates included demographics, physical exam findings (including pelvic organ prolapse as measured by POP-Q in women and digital rectal exam findings in men) and clinical testing, patient-reported measures at baseline as described above, and whether participants received any prior treatment for LUTS. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

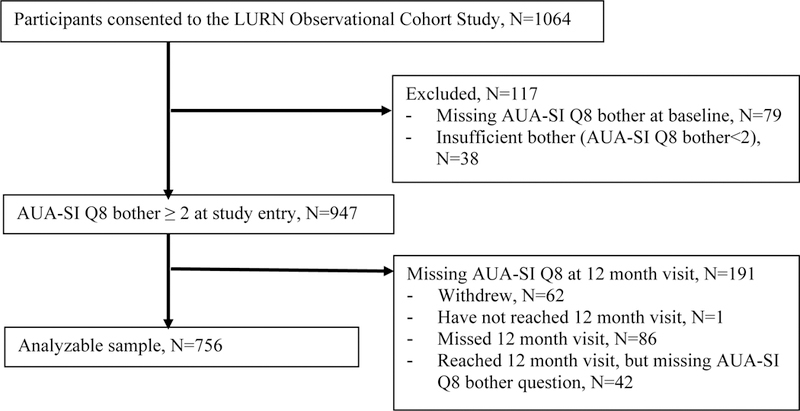

The STROBE diagram for this study is shown in Figure 1. Among 1064 participants who consented to the LURN study, 756 participants met the inclusion criteria for this study, i.e., had sufficient bother at study entry and were not missing at 12 months. Based on responses to AUA-SI Question 8 at baseline and 12 months, 121 (16.0%) of these treatment-seeking participants had worsened bother and 635 (84.0%) did not worsen (Table 1). Age and sex were similarly distributed across the two groups. However, the worsened group had a higher proportion of non-white participants and lower levels of education. The two groups were similar on most physical exam and clinical characteristics. However, the worsened group had higher BMI, and diabetes mellitus and sleep apnea were more prevalent. The proportion of participants who had received LUTS treatment prior to enrollment was similar in the two groups. Classification into the worsened or non-worsened group was not associated with previously reported symptom-based cluster membership15,16.

Figure 1.

STROBE Diagram for the LURN Study Cohort

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline

| Patient Characteristics | Total (n=756) |

Worsened (n=121) |

Not Worsened (n=635) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age mean (SD) | 59.3 (13.6) | 60.2 (11.7) | 59.2 (13.9) | 0.809 |

| Sex n (%) | 0.997 | |||

| Male | 381 (50%) | 61 (50%) | 320 (50%) | |

| Female | 375 (50%) | 60 (50%) | 315 (50%) | |

| Raceβ n (%) | 0.032 | |||

| White | 615 (82%) | 90 (74%) | 525 (83%) | |

| African-American | 81 (11%) | 21 (17%) | 60 (9%) | |

| Other | 57 (8%) | 10 (8%) | 47 (7%) | |

| Ethnicity n (%) | 0.699 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 31 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 28 (4%) | |

| Non-Hispanic/Non-Latino | 712 (94%) | 116 (96%) | 596 (94%) | |

| Ethnicity unknown | 13 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 11 (2%) | |

| Educationβ n (%) | 0.011 | |||

| < HS Diploma/GED | 20 (3%) | 6 (5%) | 14 (2%) | |

| HS Diploma/GED | 73 (10%) | 18 (15%) | 55 (9%) | |

| Some college/tech school-no degree | 163 (22%) | 30 (25%) | 133 (21%) | |

| Associate’s degree | 66 (9%) | 15 (12%) | 51 (8%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 194 (26%) | 28 (23%) | 166 (27%) | |

| Graduate degree | 226 (30%) | 24 (20%) | 202 (33%) | |

| Physical Exam and Clinical Information | ||||

| BMIβ (kg/m2)β mean (SD) | 30.4 (6.9) | 31.7 (7.6) | 30.2 (6.7) | 0.036 |

| PVR (mL)μ median (IQR) | 25.0 (3.0–70.0) | 30.0 (15.0–60.0) | 23.0 (0.0–72.0) | 0.111 |

| Current or Former Smokerβ n (%) | 311 (41%) | 52 (43%) | 259 (41%) | 0.673 |

| Number of alcoholic drinks per weekβ n (%) | 0.735 | |||

| 0 to 3 drinks per week | 447 (60%) | 74 (61%) | 373 (60%) | |

| 4 to 7 drinks per week | 109 (15%) | 17 (14%) | 92 (15%) | |

| 8+ dinks per week | 54 (7%) | 6 (5%) | 48 (8%) | |

| Has not had alcohol in the past | 137 (18%) | 24 (20%) | 113 (18%) | |

| Hypertensionβ n (%) | 332 (44%) | 60 (50%) | 272 (43%) | 0.175 |

| Diabetes n (%) | 120 (16%) | 28 (23%) | 92 (14%) | 0.017 |

| Sleep Apneaβ n (%) | 173 (23%) | 37 (31%) | 136 (21%) | 0.026 |

| Psychiatric Diagnosis n (%) | 276 (37%) | 46 (38%) | 230 (36%) | 0.707 |

| Colorectal Disease n (%) | 63 (8%) | 15 (12%) | 48 (8%) | 0.078 |

| History of UTI**β n (%) | 257 (34%) | 46 (39%) | 211 (34%) | 0.232 |

| Bladder/urethral traumaβ n (%) | 13 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 10 (2%) | 0.448 |

| Family History of LUTS n (%) | 218 (29%) | 34 (28%) | 184 (29%) | 0.845 |

| Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (Females only; available for a subset n=339), median (IQR) |

||||

| POPAaβ | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.0) | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.0) | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.0) | 0.760 |

| POPBaβ | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.0) | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.0) | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.0) | 0.921 |

| POPCλ | −7.0 (−8.0 to −5.0) | −7.0 (−8.0 to −6.0) | −6.5 (−8.0 to −5.0) | 0.080 |

| POPGHλ | 3.0 (2.0 to 4.0) | 3.0 (2.0 to 3.5) | 3.0 (2.0 to 4.0) | 0.854 |

| POPPBλ | 3.0 (2.0 to 3.5) | 3.0 (3.0 to 4.0) | 3.0 (2.0 to 3.5) | 0.082 |

| POPTVLλ | 9.0 (8.0 to 10.0) | 9.5 (8.0 to 10.0) | 9.0 (8.0 to 10.0) | 0.219 |

| POPApβ | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.5) | −2.8 (−3.0 to −2.0) | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.5) | 0.510 |

| POPBpβ | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.5) | −2.8 (−3.0 to −2.0) | −2.0 (−3.0 to −1.5) | 0.499 |

| POPD$ | −8.0 (−9.0 to −6.0) | −9.0 (−9.8 to −7.5) | −8.0 (−9.0 to −6.0) | 0.045 |

| International Index of Erectile Function (Males only) λ mean (SD) |

14.9 (11.4) | 12.3 (11.0) | 15.4 (11.4) | 0.106 |

| Prostate findings (Males only) ¥ n (%) | 0.595 | |||

| Nodule/Anomaly | 6 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Normal/enlarged prostate | 319 (98%) | 51 (100%) | 268 (98%) | |

| Any prior LUTS treatment | 511 (68%) | 89 (74%) | 422 (67%) | 0.132 |

| Cluster Membership in LURN | ||||

| Males γ | (n=381) | (n=61) | (n=320) | 0.211 |

| Cluster 1 | 120 (33%) | 15 (26%) | 105 (34%) | |

| Cluster 2 | 64 (17%) | 10 (17%) | 54 (17%) | |

| Cluster 3 | 84 (23%) | 11 (19%) | 73 (24%) | |

| Cluster 4 | 99 (27%) | 22 (38%) | 77 (25%) | |

| Females | (n=375) | (n=60) | (n=315) | 0.150 |

| Cluster 1 | 88 (23%) | 9 (15%) | 79 (25%) | |

| Cluster 2 | 56 (15%) | 9 (15%) | 47 (15%) | |

| Cluster 3 | 179 (48%) | 29 (48%) | 150 (48%) | |

| Cluster 4 | 52 (14%) | 13 (22%) | 39 (12%) | |

p-value from Chi-square or Fisher’s exact or Wilcoxon two-sample test;

History of UTI assessed as more than 2 UTIs in the past year for women and any previous UTIs for men;

Missing <2%;

Missing 2–5%;

Missing 5–10%;

Missing 15%;

Missing 16%;

Missing 30%

Several patient-reported measures at baseline differed significantly between the worsened and not worsened groups (Table 2). The worsened group was 4.6 (standardized effect size = 0.23 SDs), 6.2 (0.22 SDs), and 5.0 (0.24 SDs) points higher in severity than the not worsened group for LUTS Tool frequency, urgency, and urinary incontinence measures (all p<0.05). Other LUTS Tool severity measures and AUA-SI scores were not significantly different between groups. The worsened group was also more severe on several PROMIS measures including bowel incontinence, depression, anxiety, physical function, and sleep disturbance. Other measures including PROMIS diarrhea and constipation, urologic pain measured by the GUPI, childhood traumatic events scale, and levels of stress measured by PSS were not statistically different between groups.

Table 2:

Patient Reported Measures at Baseline

|

Total

(n=756) |

Worsened (n=121) |

Not Worsened

(n=635) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUTS Tool Frequency Scoreγ mean (SD) | 52.2 (19.5) | 56.1 (20.6) | 51.5 (19.3) | 0.037 |

| LUTS Tool Post-micturition Scoreβ mean (SD) | 47.7 (24.8) | 50.0 (24.7) | 47.2 (24.8) | 0.152 |

| LUTS Tool Urgency Scoreγ mean (SD) | 46.6 (27.7) | 51.8 (29.3) | 45.6 (27.2) | 0.033 |

| LUTS Tool Voiding Difficulty Scoreγ mean (SD) | 34.3 (22.2) | 33.5 (22.0) | 34.4 (22.3) | 0.748 |

| LUTS Tool Bladder/micturition Discomfort Scoreβ mean (SD) | 14.5 (20.5) | 18.9 (24.1) | 13.6 (19.6) | 0.057 |

| LUTS Tool UI Scoreλ mean (SD) | 31.1 (21.3) | 35.3 (20.4) | 30.3 (21.4) | 0.012 |

| AUA-SIλ mean (SD) | 13.3 (6.5) | 14.1 (7.1) | 13.1 (6.4) | 0.278 |

| PROMIS GI Bowel Incontinence (raw scale)γ mean (SD) | 5.0 (2.1) | 5.5 (2.6) | 4.9 (2.0) | 0.018 |

| PROMIS GI Diarrhea (T score)β mean (SD) | 47.9 (8.7) | 48.6 (9.9) | 47.8 (8.4) | 0.674 |

| PROMIS GI Constipation (T score)γ mean (SD) | 50.1 (8.4) | 50.7 (9.1) | 50.0 (8.3) | 0.537 |

| GUPI¥ mean (SD) | 14.3 (7.6) | 15.1 (8.7) | 14.1 (7.4) | 0.491 |

| Childhood Traumatic Events Scaleγ n (%) | 519 (71%) | 85 (73%) | 434 (71%) | 0.761 |

| PROMIS Depression (T score)β mean (SD) | 48.6 (8.7) | 51.7 (9.8) | 48.1 (8.3) | <.001 |

| PROMIS Anxiety (T score)β mean (SD) | 49.1 (9.0) | 51.2 (10.5) | 48.7 (8.6) | 0.021 |

| PROMIS Physical Function (T score)γ, a mean (SD) | 48.8 (9.7) | 45.7 (10.3) | 49.4 (9.5) | <.001 |

| PROMIS Sleep Disturbance (T score)β mean (SD) | 52.4 (8.5) | 54.6 (9.6) | 52.0 (8.2) | 0.007 |

| PSSλ mean (SD) | 11.8 (7.3) | 13.1 (7.7) | 11.6 (7.2) | 0.058 |

p-value from Wilcoxon two-sample test;

Lower score indicates less physical function.

Missing <2%;

Missing 2–5%;

Missing 5–10%;

Missing 29%

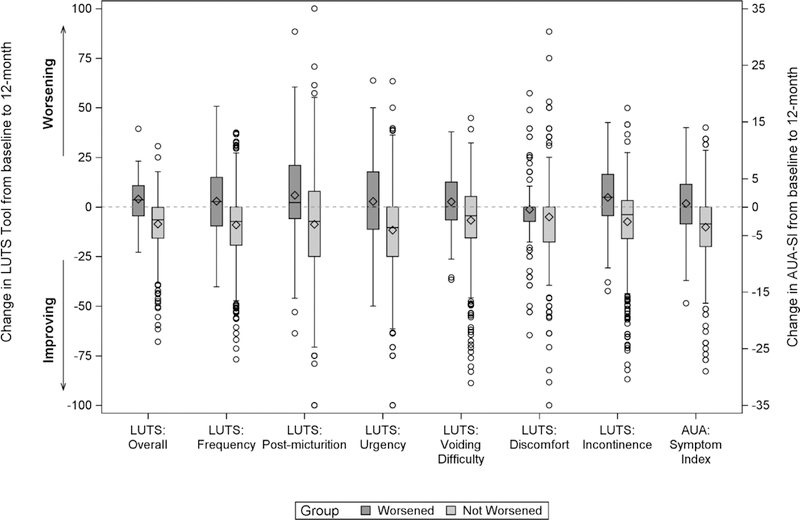

Changes in LUTS severity as measured by the LUTS Tool and the AUA-SI were similar in the two groups (Figure 2). For the worsened group, urinary incontinence and post-micturition symptoms significantly worsened (raw delta [standardized effect size]=4.8 [0.21 SDs] and 5.9 [0.21 SDs], p=0.004 and p=0.01, respectively), whereas several other LUTS measures and the AUA-SI also worsened but not significantly. For the not worsened group, on average, all LUTS Tool measures and the AUA-SI improved from baseline to 12 months by 5.1–11.7 (0.29 – 0.49 SDs) and 3.6 (0.54 SDs) units, respectively (all p<0.001). Overall LUTS Tool scores increased by 3.9 (0.25 SDs) for the worsened group (p=0.002) and decreased by 8.6 (0.65 SDs) for the not worsened group (p<0.001).

Figure 2:

LUTS Tool and AUA-SI Changes between Baseline and 12 Month by Bother Groups

Factors at baseline associated with 12-month bother identified through multiple linear regression are shown in Table 3. Among men, non-white race, sleep apnea, bladder trauma, and GI bowel incontinence were associated with higher 12-month bother ratings [β (95% Confidence Interval [95% CI]) = 0.59 (0.22, 0.97), 0.21 (−0.11, 0.53), 0.70 (−0.42, 1.81), and 0.22 (−0.10, 0.54), respectively]. More severe urinary frequency and incontinence measured by the LUTS Tool and level of stress measured by the PSS were also associated with higher bother ratings at 12 months [β (95% CI) = 0.12 (0.05, 0.19), 0.16 (0.07, 0.26), and 0.12 (0.04, 0.21), respectively, per one-tenth increase in the entire scale]. Hypertension was associated with lower bother ratings at 12 months. Among women, a one-unit increase in baseline bother rating was associated with a 0.3-unit (95% CI = 0.16–0.44) increase in bother rating at 12 months. More severe urinary urgency and frequency were associated with higher 12-month bother ratings [β (95% CI) = 0.10 (0.03, 0.17) and 0.08 (−0.01, 0.18), respectively, per one-tenth increase in the entire scale]. Higher physical function was associated with lower 12-month bother ratings [β (95% CI) = −0.08 (−0.16, −0.00) for 5 units increase in the PROMIS T-score].

Table 3.

Factors associated with AUA-SI bother score 12months after study enrollment based on multiple linear regression

| Predictor | Estimate (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Men only | ||

| Non-white vs. White | 0.59 (0.22, 0.97) | 0.0020 |

| Hypertension | −0.32 (−0.61, −0.04) | 0.0260 |

| Sleep Apnea | 0.21 (−0.11, 0.53) | 0.2010 |

| Bladder Trauma | 0.70 (−0.42, 1.81) | 0.2207 |

| LUTS Tool Frequency Score (per 10 units increase) | 0.12 (0.05, 0.19) | 0.0007 |

| LUTS Tool Urinary Incontinence Score (per 10 units increase) | 0.16 (0.07, 0.26) | 0.0009 |

| PROMIS GI Bowel Incontinence: Any vs. None* | 0.22 (−0.10, 0.54) | 0.1768 |

| PSS (per 4 units increase) | 0.12 (0.04, 0.21) | 0.0055 |

| Women only | ||

| Bother at Baseline (per 1 unit increase) | 0.30 (0.16, 0.44) | <.0001 |

| LUTS Tool Urgency Score (per 10 units increase) | 0.10 (0.03, 0.17) | 0.0033 |

| LUTS Tool Frequency Score (per 10 units increase) | 0.08 (−0.01, 0.18) | 0.0686 |

| PROMIS Physical Function a (per 5 units increase) | −0.08 (−0.16, −0.00) | 0.0471 |

PROMIS GI Bowel Incontinence was used as a binary covariate (any vs. none) because 71% of males reported no bowel incontinence.

Lower score indicates less physical function.

Results from multivariable logistic regression models are shown in Table 4. Among men, non-white participants and those with diabetes were more likely to be in the worsened group [odds ratio (OR) (95% CI) = 1.79 (0.95, 3.39) and 1.68 (0.86, 3.26), respectively]. Among women, diabetes was also associated with higher odds of being in the worsened group with similar effect size [OR (95% CI) =1.78 (0.86, 3.65)]. In addition, women who had LUTS treatment prior to baseline and higher levels of depression as measured by PROMIS T-scores were also associated with higher odds of being in the worsened group [OR (95% CI) = 2.59 (1.24, 5.40) and 1.30 (1.11, 1.53) per 5 unit increase, respectively].

Table 4.

Factors associated with worsened LUTS bother 12 months after study enrollment based on binomial logistic regression

| Predictor | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Men only | ||

| Non-white vs. white | 1.79 (0.95, 3.39) | 0.0740 |

| Diabetes | 1.68 (0.86, 3.26) | 0.1285 |

| Women only | ||

| Diabetes | 1.78 (0.86, 3.65) | 0.1185 |

| Any Prior LUTS Treatment | 2.59 (1.24, 5.40) | 0.0112 |

| PROMIS Depression (per 5 units increase) | 1.30 (1.11, 1.53) | 0.0013 |

Discussion

Most clinical studies of LUTS focus on treatment outcomes and are typically focused on the improvement of a particular symptom or set of symptoms. In most of these studies and in most clinicians’ experiences, there is a subgroup of patients who continue to be bothered by symptoms or even report worsened bother despite receiving treatment. Given the range of LUTS in patients who worsen despite care, we sought to examine the possibility that—independent of the treatment of LUTS—patient factors may play a substantial role in treatment failure. If such factors could be identified prospectively, treatment decision-making could be impacted, and pre-treatment counseling could be tailored towards patient-centered outcomes, rather than population-based outcomes.

Our study examined a large cohort of care-seeking patients experiencing a range of LUTS (and in most cases experiencing multiple symptoms). Participants were categorized by changes in bother over a 12-month observation period using the AUA-SI bother question. We examined patient factors related to worsening of LUTS bother, treatment notwithstanding.

Our study found baseline factors associated with worsened bother at 12 months among men: non-white race, diabetes, worse urinary frequency and incontinence, and higher levels of stress. Among women, those with diabetes, prior LUTS treatment, more severe bother at baseline, urinary urgency and frequency, higher levels of depression, and worse physical function had more severe LUTS bother at 12 months. BMI, several comorbidities (including colorectal disease, history of UTI, bladder/urethral trauma, and family history of LUTS), and clinical exam findings were not associated with worsened LUTS bother over time in this cohort of patients seeking care at tertiary referral centers.

Our study is unique in examining patient characteristics at study entry associated with LUTS bother rating 12 months later irrespective of any treatment received in that 12-month study period. Prior studies have reported on longitudinal symptom trajectory and patient characteristics associated with persistence of LUTS severity in the context of specific treatments, and highlighted associated factors such as high bother scores, lifestyle factors, higher prostate volumes, greater PVR, and higher PSA. 18–22 However, our objective was to identify prognostic factors associated with higher bother ratings 12 months later, agnostic to treatments rendered.

Some limitations should be noted. First, our definition of LUTS bother is based solely on patient self-report on a single survey item. However, in clinical practice, LUTS bother is diagnosed based on patients’ self-reported bother and using the AUA-SI. Second, controls were not included as a comparison group. Third, we followed a cohort of mostly white, English-speaking, care-seeking patients. Non-English-speaking patients may experience barriers to accessing care 23–25. Non-care-seeking patients may have ongoing symptoms, but their bother may be minor and not impact their overall QOL 26. Fourth, we did not adjust for the presence or absence of treatments received during the study. Given the observational nature of this study, we did not intend to make causal links between treatment and observed symptom changes. Lastly, there may be other factors that affect symptom bother that were not included in our study. For example, patients may have adopted coping mechanisms prior to or during the study period. Strategies like timed voiding, changes in fluid intake, or regular use of pads may have affected daily activities and urinary QOL.

These limitations notwithstanding, this longitudinal study of LUTS bother, which included data from men and women who sought care from six geographically-dispersed urology and urogynecology clinics in the U.S., demonstrates important and clinically-relevant associations between patient factors and worsened LUTS bother over time.

Conclusion

LUTS bother was more common among those with greater urinary symptom severity, nonwhites, and those with depression and/or stress. These findings suggest the underlying complexity of LUTS and the challenges patients and providers face in managing lower urinary tract dysfunction. These results may have clinical applicability in identifying patients with severe LUTS bother and guide patient counseling and treatment decision-making.

Acknowledegements

This is publication number 20 of the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN).

This study is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases through cooperative agreements (grants DK097780, DK097772, DK097779, DK099932, DK100011, DK100017, DK097776, DK099879).

Research reported in this publication was supported at Northwestern University, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Siddiqui is supported by grant K23-DK110417 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

The following individuals were instrumental in the planning and conduct of this study at each of the participating institutions:

Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (DK097780): PI: Cindy Amundsen, MD, Kevin Weinfurt, PhD; Co-Is: Kathryn Flynn, PhD, Matthew O. Fraser, PhD, Todd Harshbarger, PhD, Eric Jelovsek, MD, Aaron Lentz, MD, Drew Peterson, MD, Nazema Siddiqui, MD, Alison Weidner, MD; Study Coordinators: Carrie Dombeck, MA, Robin Gilliam, MSW, Akira Hayes, Shantae McLean, MPH

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA (DK097772): PI: Karl Kreder, MD, MBA, Catherine S Bradley, MD, MSCE, Co-Is: Bradley A. Erickson, MD, MS, Susan K. Lutgendorf, PhD, Vince Magnotta, PhD, Michael A. O’Donnell, MD, Vivian Sung, MD; Study Coordinator: Ahmad Alzubaidi

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL (DK097779): PIs: David Cella, Brian Helfand, MD, PhD; Co-Is: James W Griffith, PhD, Kimberly Kenton, MD, MS, Christina Lewicky-Gaupp, MD, Todd Parrish, PhD, Jennie Yufen Chen, PhD, Margaret Mueller, MD; Study Coordinators: Sarah Buono, Maria Corona, Beatriz Menendez, Alexis Siurek, Meera Tavathia, Veronica Venezuela, Azra Muftic, Pooja Talaty, Jasmine Nero. Dr. Helfand, Ms. Talaty, and Ms. Nero are at NorthShore University HealthSystem.

University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI (DK099932): PI: J Quentin Clemens, MD, FACS, MSCI; Co-Is: Mitch Berger, MD, PhD, John DeLancey, MD, Dee Fenner, MD, Rick Harris, MD, Steve Harte, PhD, Anne P. Cameron, MD, John Wei, MD; Study Coordinators: Morgen Barroso, Linda Drnek, Greg Mowatt, Julie Tumbarello

University of Washington, Seattle Washington (DK100011): PI: Claire Yang, MD; Co-I: John L. Gore, MD, MS; Study Coordinators: Alice Liu, MPH, Brenda Vicars, RN

Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis Missouri (DK100017): PI: Gerald L. Andriole, MD, H. Henry Lai; Co-I: Joshua Shimony, MD, PhD; Study Coordinators: Susan Mueller, RN, BSN, Heather Wilson, LPN, Deborah Ksiazek, BS, Aleksandra Klim, RN, MHS, CCRC

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Kidney, Urology, and Hematology, Bethesda, MD: Project Scientist: Ziya Kirkali MD; Project Officer: Christopher Mullins PhD; NIH Personnel: Tamara Bavendam, MD, Robert Star, MD, Jenna Norton

Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, Data Coordinating Center (DK097776 and DK099879): PI: Robert Merion, MD, FACS; Co-Is: Victor Andreev, PhD, DSc, Brenda Gillespie, PhD, Gang Liu, PhD, Abigail Smith, PhD; Project Manager: Melissa Fava, MPA, PMP; Clinical Study Process Manager: Peg Hill-Callahan, BS, LSW; Clinical Monitor: Timothy Buck, BS, CCRP; Research Analysts: Margaret Helmuth, MA, Jon Wiseman, MS; Project Associate: Julieanne Lock, MLitt

Abbreviations

- AUA-SI

American Urological Association Symptom Index

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- DCC

Data coordinating Center

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- GUPI

Genitourinary pain index

- LURN

Symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction research network

- LUTS

Lower urinary tract symptoms

- MCID

Minimal clinically important difference

- OAB

Overactive bladder

- OR

Odds ratio

- POP-Q

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification

- PROMIS

Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system

- PSS

Perceived Stress Scale

- PVR

Post-void residual

- QOL

Quality of life

- SD

Standard deviation

- UI

Urinary incontinence

References

- 1.Roehrborn C Benign prostatic hyperplasia: etiology, pathophysiology, epidemiology and natural history. In: Walsh P, ed. Campbell’s Urology; 8 ed. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia, PA; 2012:2570–2610. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potts J Essential urology: a guide to clinical practice. 2 ed: Humana Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. European Urology. 52(2):389–396, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/826898_transcript. Accessed 6/12, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi S, Takei M, Nishizawa O, et al. Clinical Guideline for Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms.8(1):5–29, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang CC, Weinfurt KP, Merion RM, Kirkali Z. Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network. The Journal of Urology. 196(1):146–152, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron A, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Smith A, et al. Baseline Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Patients Enrolled in LURN: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Study. Journal of Urology. 199(4):1023–1031, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology;63(11):1179–1194, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemens J, Calhoun E, Litwin M, et al. Validation of a modified National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index to assess genitourinary pain in both men and women. Urology. 74(5):983–987,2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 24(4):385–396, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pennebaker J, Susman J. Disclosure of traumas and psychosomatic processes. Social Science & Medicine. 26(3):327–332,1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coyne K, Barsdorf A, Thompson C, et al. Moving towards a comprehensive assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Neurourology and Urodynamics.31(4):448–454,2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry M, Fowler FJ, O’Leary M, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. Journal of Urology. 148(5):1549–1557,1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmuth MSA, Andreev V, Liu G, et al. Use of Euclidean Length to Measure Urinary Incontinence Severity Based on the Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Tool. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 218(3):357–359,2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreev VP, Liu G, Yang CC, et al. Symptom Based Clustering of Women in the LURN Observational Cohort Study. J Urol;200(6):1323–1331, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu GAV, Helmuth ME, Yang CC, Smith AR, Wiseman JB, Merion RM, Lai HH, Erickson Bam Cella D, Griffith JW, Gore JK, DeLancey JO, Kirkali Z. Symptom-based Clustering of Men in the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN) Observational Cohort Study. . Journal of Urology. 2018, In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological). 57(1):289–300, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishriki S, Aboumarzouk O, Graham J, Lam T, Somani B. Baseline symptom score and flow rate can predict failure of medical treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms: prospective 12-year follow-up study. Urology. 81(2):390–394, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall L, Holton K, Parsons J, et al. Lifestyle and health factors associated with progressing and remitting trajectories of untreated lower urinary tract symptoms among elderly men. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 17(3):265–272, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong S, Ko W, Kim S, Chung B. Identification of baseline clinical factors which predict medical treatment failure of benign prostatic hyperplasia: an observational cohort study. European Urology. 44(1):94–99, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford E, Wilson S, McConnell J, et al. Baseline factors as predictors of clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia in men treated with placebo. Journal of Urology. 175(4):1422–1426, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bechis S, Kim M, Wintner A, Kreydin E. Differential Response to Medical Therapy for Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports. 10(2):177–185, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flores G Perspective: Language Barriers to Health Care in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 355:229–231, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blasco P, Valdivia M, Oña M, Roset M, Mora A, Hernández M. Clinical characteristics, beliefs, and coping strategies among older patients with overactive bladder. Neurourology and Urodynamics.36(3):774–779, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nørby B, Nordling J, Mortensen S. Lower urinary tract symptoms in the danish population: a population-based study of symptom prevalence, health-care seeking behavior and prevalence of treatment in elderly males and females. European Urology.47(6):817–823, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffith J, Messersmith E, Gillespie B, et al. Reasons for Seeking Clinical Care for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Mixed-Methods Study. Journal of Urology. 199(2):528–535, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]