Abstract

Background:

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. Screening can aid in early disease detection, when treatment is more effective. Although there are currently no consensus guidelines regarding skin screening for pediatric populations with elevated familial risk for melanoma, at-risk children with the help of their parents and healthcare providers, may implement skin self-exams. Healthcare providers may also recommend screening practices for these children. The goal of the current study was to describe current screening behaviors and provider recommendation for screening among children of melanoma survivors.

Methods:

Parents of children with a family history of melanoma completed a questionnaire that included items on children’s screening frequency, thoroughness, and who performed the screening.

Results:

Seventy-four percent of parents reported that their children (mean age=9.0 years, SD=4.8) had engaged in parent-assisted skin self-exams (SSE) in the past six months. Only 12% of parents reported that children received SSEs once per month (the recommended frequency for adult melanoma survivors). In open-ended responses, parents reported that healthcare providers had provided recommendations around how to conduct SSEs, but most parents did not report receiving information on recommended SSE frequency. Twenty-six percent of parents (n=18) reported that children had received a skin exam by a healthcare provider in the past six months.

Conclusions:

The majority of children with a family history of melanoma are reportedly engaging in skin exams despite the lack of guidelines on screening in this population. Future melanoma preventive interventions should consider providing families guidance about implementing screening with their children.

Introduction

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer, and it will be diagnosed in more than 91,000 individuals in the United States in 2018 [1]. Melanoma is being increasingly diagnosed in populations below the age of 19 (incidence rate=6.0 per 1,000,000, increasing 2% per year) [2], and is the second most common cancer among 15 to 29 year olds [3]. Risk factors for melanoma include modifiable factors, such as exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR), and non-modifiable factors, such as having fair skin, a large number of moles and a family history of melanoma [4]. Family history is perhaps the strongest non-modifiable risk factor, with 10% of individuals diagnosed with melanoma having a family history of the disease [4]. The primary way to mitigate familial risk for melanoma is to decrease UVR exposure and practice melanoma preventive efforts starting in childhood [5]. If detected early, melanoma is more effectively treated and frequently curable [6]. Early detection of melanoma involves screening through total body skin exams (TBSE) by a healthcare provider and individuals conducting their own skin self-exams (SSE). SSE consists of the careful and deliberate examination of all areas of one’s skin, including the back, scalp, and soles of feet, for potentially suspicious new or changing moles. Patients are often taught to use the ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border, Color, Diameter, Evolving) [7] to identify skin lesions that should be examined by a healthcare provider. Annual TBSE and monthly SSE are recommended for individuals who are at increased risk for developing melanoma, including children with a family history of the disease [8, 9].

A number of interventions to improve screening practices among adults at increased risk for melanoma have demonstrated positive effects on screening frequency and thoroughness [10, 11]. Children at increased risk for melanoma, including children who have a parent with a history of the disease and thus have a two-fold increased risk for developing melanoma later in life [12, 13], have received comparatively less focus than at-risk adults. Skin cancer prevention recommendations for children at increased risk include counseling to minimize their UVR exposure to reduce their risk for skin cancer [14]. A potentially important prevention recommendation that has not been addressed is the role of counseling regarding skin screening for pediatric populations with elevated familial risk for melanoma. Despite this gap in recommendations, it is possible that at-risk children, with the help of their parents, may implement skin self-exams or that healthcare providers recommend screening practices for these children. Indeed, the only study to date that has examined screening behaviors among minor children of melanoma survivors found that 38% of survivors reported that their children had ever received a TBSE from a healthcare provider and 75% of survivors reported ever conducting SSEs with their children [15]. The study also revealed that female survivors were more likely to report ever performing a SSE with their child. What remains unknown is the frequency with which children of melanoma survivors conduct SSEs, how thorough child SSEs are, and whether other family members (e.g., parents) assist with child SSEs. Additionally, it remains unknown whether melanoma survivors and their children receive recommendations from healthcare providers to conduct SSEs and what those recommendations may be, particularly in the absence of consensus guidelines for this at-risk population. In order to inform the design of comprehensive interventions focused on melanoma prevention among at-risk pediatric populations, the current study sought to describe skin cancer screening practices among children of melanoma survivors, and the frequency and content of healthcare provider recommendations around screening for these at-risk children.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Parents (n=69) were eligible to participate if they were the primary caregiver to at least one child under age 18 who had a biological parent with a history of melanoma. Participants reported on all of their children as a group, and all together parents reported on a total of 161 children under 18 years of age. Parent participants were recruited in several ways, including via a letter sent to patients who received care for melanoma at an NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center or parents who had participated in prior melanoma studies and agreed to be contacted about future research opportunities. Study fliers were also made available in medical clinics serving patients with a personal or family history of melanoma, to local organizations serving melanoma survivors and their families, and at a free skin cancer screening at a cancer center. In total, 140 out of 419 adults screened were eligible to participate. The most common reason for ineligibility was not having a biological child under age 18 (43%). Of the 140 eligible individuals, 69 parents participated in the current study (recruitment rate=49%). In addition, one participant with a personal history of melanoma had a spouse who also participated, which resulted in a final sample of 70 participating adults. We randomly selected one parent from this family to be included in analyses to maintain statistical independence. Participants completed questionnaires in person or via mail, and received a gift card for questionnaire completion. Each participant provided informed consent. All study procedures were approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Participants were asked to complete a self-reported questionnaire that assessed child SSE, and were asked to report on their children under 18 years of age as a group. Parents were asked to report on child SSE frequency (i.e., every day, every 2–3 days, every week, every 2 weeks, every month, every 2 months, every 3 months, every 6 months, never, some other amount) and SSE thoroughness measured by the number of body parts examined using a checklist of 14 body sites (head and scalp, face, ears, neck, shoulders, back, chest, stomach, arms/hands, genitals/privates, buttocks, legs, tops of feet, bottoms of feet) [16]. Parents reported on which individuals checked the child’s skin (child, parent, another individual). Parents were also asked to specify which healthcare providers (if any) had recommended child SSEs, and if so, the content of the provider’s recommendation. Parents were also asked whether their child had received a TBSE from a healthcare provider in the past six months. Finally, participants were asked to complete items assessing parent and child demographic characteristics including age, race, sex, health insurance status, adult relationship to child, household income, parent marital status and parent education level.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant and child demographic characteristics, frequency of child screening behaviors, and proportion of parents who reported receiving an SSE recommendation from a healthcare provider. For inferential statistical analyses, screening frequency was dichotomized into ever screened versus never screened. In order to examine factors associated with screening behaviors in children, correlational analyses were performed to examine potential associations between implementation of TBSE and implementation of SSE, and between both types of screening and parent demographic characteristics. All quantitative analyses were conducted using SPSS version 24. Content analysis was used to summarize parent-reported recommendations received from healthcare providers about child screening [17].

Results

Demographic characteristics for the 69 parent participants are summarized in Table 1. In terms of SSE frequency, the vast majority of parents (74%) reported that their children had conducted an SSE at least once in the past six months. Twelve percent reported that their children received SSEs once per month (the recommended frequency for adult melanoma survivors), while the majority of parents reported that their children conduct SSEs more often (16%) or less often (43%) than monthly (Table 2). Of the parents who reported that their children had engaged in SSEs, 78% reported that one parent had checked the child’s skin, and 22% reported that both parents had checked the child’s skin. Sixteen percent of parents reported that children had participated in checking their own skin with a parent. Regarding child SSE thoroughness, parents reported that on average, approximately 11 out of 15 body parts were checked (M=10.7, SD=3.4, range=2–14). Age of parent was negatively correlated with child SSE occurrence, such that younger parent age (Screeners: M=38.7 years, SD=6.9; Non-screeners: M=42.9 SD=5.7) was associated with reported occurrence of child SSE (rpb= −0.28, n=69, p=.02). There were no other parent demographic characteristics associated with child SSE occurrence. Child SSE occurrence was not significantly associated with child TBSE occurrence. One-quarter (n=18, 26%) of parents reported that their children received a TBSE from a healthcare provider in the past six months. There were no significant correlations between reported child TBSE occurrence and parent demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics (n=69)

| Parents | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | Range |

| 40 (6.8) | 21–56 | |

| Sex | n (%) | |

| Male | 14 (20) | |

| Female | 55 (80) | |

| Household income | Median | Range |

| $100,0000+ | ≤$9,999 – ≥$100,000 | |

| Relationship to childa | n (%) | |

| Mother | 53 (77) | |

| Father | 14 (20) | |

| Step-Parent | 3 (4) | |

| Grandparent | 1 (1) | |

| Child characteristics based on parent-report | ||

| Race | n (%) | |

| White | 66 (96) | |

| Black | 1 (1) | |

| Bi-racial | 2 (3) | |

| Has health insurance | n (%) | |

| Yes | 68 (99) | |

| No | 1 (1) | |

| Age | Mean (SD) | Range |

| 9.0 (4.8) | 1–17 | |

N=71 because two participants reported that they were both a “parent” and a “step-parent.”

Table 2.

Child screening frequency and skin self-exam thoroughness per parent-report

| Child received TBSE in past six months | n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 (26) | |||||

| Child received SSE in past six months | n (%) | ||||

| 49 (74) | |||||

| Frequency of child SSE in past six months | <1x/month n (%) | 1x/month n (%) | >1x/month n (%) | Never n (%) | |

| 30 (43) | 8 (12) | 11 (16) | 20 (29) | ||

| Who assisted with child SSE in past six months1 | Child2 n (%) | Parent who participated in the study n (%) | Other parent n (%) | Other n (%) | |

| 8 (16) | 44 (90) | 16 (33) | 0 (0) | ||

| SSE thoroughness in past six months (Body parts checked) | Checked n (%)1 | ||||

| Head and scalp | 39 (80) | ||||

| Face | 46 (94) | ||||

| Ears | 36 (78) | ||||

| Neck | 43 (88) | ||||

| Shoulders | 43 (88) | ||||

| Back | 46 (94) | ||||

| Chest | 41 (84) | ||||

| Stomach | 40 (82) | ||||

| Arms/Hands | 45 (92) | ||||

| Genitals/Privates | 16 (33) | ||||

| Buttocks | 28 (57) | ||||

| Legs | 43 (88) | ||||

| Tops of feet | 33 (67) | ||||

| Bottoms of feet | 24 (49) | ||||

Percentages do not add up to 100% because participants were asked to check all that apply.

All 8 children were assisted in doing SSE by a parent.

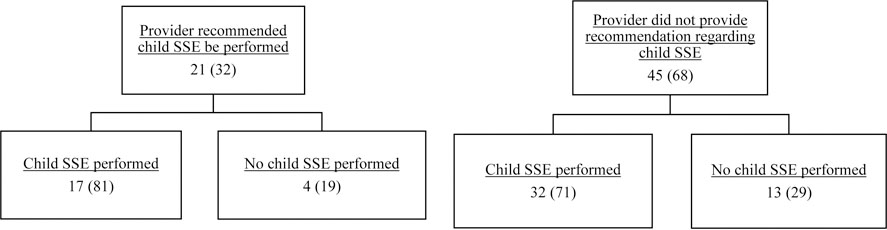

In total, 32% (n=21) of parents reported that they had received a recommendation from a healthcare provider that their children should conduct SSEs. Of those parents, 81% (n=17) reported that they helped their children conduct SSEs. In contrast, 68% (n=45) of parents reported not receiving a healthcare provider recommendation regarding child SSEs, and of those parents, 71% (n=32) still chose to conduct SSE with their children (Figure 1). All 21 parents that endorsed receiving a SSE recommendation from a healthcare provider reported that a doctor had provided the recommendation, and two of those parents reported that a nurse had also recommended they conduct SSEs with their children.

Figure 1.

Parent-reported receipt of recommendation from a healthcare provider about child skin self-exam implementation, n (%)

Note. N=66 due to missing data for 3 participants.

Qualitative responses on healthcare provider screening recommendations

Of the 32% of parents who reported they received a recommendation for a SSE from a healthcare provider, 90% provided an open-ended response describing the content of the recommendation. Parents reported that healthcare providers advised them to be aware of skin changes on their childrens’ bodies. These recommendations ranged from broad instructions such as, “Have [your] child be aware of their body and the changes,” to more specific instructions such as: “Check for moles or changing moles,” “Check the ABCDEs of moles,” [7] or “Look over [your] child’s skin regularly for changes in shape, color, regularity.” The vast majority (95%) of parents did not report being given information on SSE frequency. The one parent who reported receiving this information noted that she was told to conduct monthly child SSEs. Parents of older children (over age 13) noted that a healthcare provider had recommended that children perform SSEs independently: “Since they are older now, they have been told to do [SSE] themselves.” Other parents expressed not receiving any recommendations regarding SSEs in children from a healthcare provider. For instance, parents reported that dermatologists never mentioned child SSEs. Another parent remarked: “[Provider] told me I don’t need to worry much about melanoma in kids – CRAZY!” Of the parents who reported not receiving an SSE recommendation, some expressed a desire for such a recommendation: “I would have like to hear something [regarding SSE] from the pediatrician.”

Parents also volunteered information about provider recommendations about child TBSEs. Parents reported that healthcare providers gave recommendations on the importance of TBSE in their children and recommended TBSE frequency. For example, parents reported that healthcare providers recommended a variety of time frames that children should receive TBSE, ranging from yearly TBSE to every 18 months. One parent noted that they were instructed to have their children attend a mole-mapping clinic around age 16, so that they could track changes in the childrens’ moles over time [18].

Discussion

Despite the lack of consensus guidelines on skin screening among children at elevated risk for melanoma, the results of the current study indicate that, in this single site sample of melanoma survivors and their children, the vast majority (74%) of children are reportedly engaging in regular skin exams. These results are consistent with prior findings that three-quarters of children who have a parent with melanoma had ever engaged in SSE with the help of parent [15]. The current study adds to the literature by also documenting the variability in child SSE frequency. Some children (12%) are reportedly engaging in SSEs once per month, which mirrors what is recommended for adults [6, 19], while others (16%) are conducting SSEs more frequently than monthly. Higher skin cancer-related worry has been found to be associated with greater frequency of SSE in the general population, suggesting that performing SSE more frequently than monthly could be related to melanoma-specific distress in children as well as parents [20]. Interestingly, our results parallel those observed in samples of adults at high risk for melanoma, of whom 29% report optimally performing SSE, with a substantial proportion reporting more frequent screening (27%). In those adult studies, half of overscreeners attributed this behavior to high concern about melanoma due to family history of the disease (25%) or due to personal melanoma history or elevated personal risk (25%) [21]. In addition, we found that younger parent age was associated with child SSE occurrence; however, unlike other studies [15], we did not find a relationship between parent gender and children receiving screening.

Melanoma in children is uncommon and is frequently symptomatic, and as a result melanoma detection in children is not wholly dependent on engagement in SSE [22]. However, screening in at-risk children could establish a life-long habit of SSE which could facilitate early melanoma detection later in life, when melanoma is more likely to occur. Additionally, the results of the current study reveal that, regardless of whether parents receive SSE recommendations from healthcare providers, their children are engaging in SSEs, most often with help from parents. This may reflect that parents are aware of their childrens’ elevated risk for melanoma and want to engage in health behaviors that they perceive to contribute to melanoma prevention. Parents who did receive SSE recommendations from HC providers reported receiving broad recommendations, and the majority were given no information on SSE frequency. This lack of specificity could lead to parents deciding for themselves what frequency is ideal, and account for over- and underscreening. In addition, because pediatric melanoma presents differently from adult melanoma, the ABCDE criteria that melanoma survivors may be familiar with do not include features unique to pediatric melanoma [23]. Without guidance on screening in children, it is possible that parents may apply the conventional ABCDE criteria to their children when assisting with their SSEs, and are therefore unlikely to recognize a pediatric melanoma.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to obtain more detailed information on screening in children of melanoma survivors, including on frequency of screening and qualitative information regarding provider recommendation for pediatric screening. Limitations of the current study include that parents reported on their children as a group, and it included a relatively small sample from a single geographic location; however, it targeted families living in an area with a high incidence of melanoma [24]. Future interventions focused on melanoma prevention and control among at-risk pediatric populations and their families could build on the findings from the current study. For example, interventions could be delivered to the family as a unit, because parents are evidently highly involved in conducting childrens’ skin screenings. Associations between parent age and screening engagement provide insight that older parents may be less likely to engage with their children in this aspect of melanoma prevention, and therefore could benefit most from such interventions. Future studies should further explore the relationship between demographic factors and child screening to better understand what factors may influence screening. More detailed information on the types of healthcare provider giving recommendations regarding SSE could help identify where families receive information about SSE in children and suggest areas for intervention that involve healthcare providers. Additionally, future work could seek to better understand the specific beliefs and barriers that could be related to over- and underscreening (e.g., emotions like fear or anxiety could lead to both over- and underscreening [21], while barriers like feeling unsure of how to perform SSE could lead to underscreening [25]).

Although there are currently no recommendations regarding screening for children in families with a history of melanoma [14], the results of this study suggest that, nevertheless, many of these families are implementing screening with their children, and could benefit from receiving standardized recommendations about screening in their children as well as guidance on how to introduce the concept of screening to their children. Future efforts are needed to provide families with a history of melanoma comprehensive melanoma prevention interventions that include guidance about implementing screening for children.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported, in part, by an early career award from the Primary Children’s Hospital Foundation and the F. Marian Bishop grant through the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine at the University of Utah (both to Y.P.W.). We acknowledge the funding support of NIH Support Grant (P30CA08748–48) to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the Office of Communications supported by funds in conjunction with grant P30 CA042014 awarded to Huntsman Cancer Institute. In addition, this work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K07CA196985 to Y.P.W.) and the Huntsman Cancer Foundation (Y.P.W., D.G.); and National Cancer Institute R01 CA158322 (L.G.A., S.A.L.). Effort by Dr. Leachman was supported in part by the Oregon Health and Science University and the Knight Cancer Institute. Data entry for this project was completed using REDCap, which is supported by the National Cancer for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (8UL1TR000105, formerly UL1RR025764). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program. (2018). SEER Stat fact sheets: Melanoma of the skin http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html. Accessed April 18 2018.

- 2.Wong JR, Harris JK, Rodriguez-Galindo C, and Johnson KJ (2013). Incidence of childhood and adolescent melanoma in the United States: 1973–2009. Pediatrics 131(5), 846–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleyer A, Viny A, and Barr R (2006). Cancer in 15- to 29-year-olds by primary site. Oncologist 11(6), 590–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. (2016). Cancer Facts and Figures 2016 Atlanta: American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- 5.PDQ Screening and Prevention Editorial Board. (2017). Skin cancer prevention (PDQ): Health professional version. In PDQ Cancer Informations Summaries [Internet], ed. National Cancer Institute (US) Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Cancer Society. (2018). Can Melanoma Skin Cancer Be Found Early?: American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Dermatology. (2018). What to look for: ABCDEs of Melanoma. In SPOT Skin Cancer: American Academy of Dermatology. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melanoma Research Foundation. (2018). Self-Screening for Melanoma: Kid’s Guide to Self-Screening https://www.melanoma.org/understand-melanoma/preventing-melanoma/early-detection/self-screening-guide. Accessed July 12 2018.

- 9.Skin Cancer Foundation. (2018). If You Can Spot It You Can Stop It https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/early-detection/if-you-can-spot-it-you-can-stop-it. Accessed July 12 2018.

- 10.Geller AC, Emmons KM, Brooks DR, Powers C, Zhang Z, Koh HK, Heeren T, Sober AJ, Li F, and Gilchrest BA (2006). A randomized trial to improve early detection and prevention practices among siblings of melanoma patients. Cancer 107(4), 806–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveria SA, Dusza SW, Phelan DL, Ostroff JS, Berwick M, and Halpern AC (2004). Patient adherence to skin self-examination: effect of nurse intervention with photographs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 26(2), 152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho E, Rosner BA, Feskanich D, and Colditz GA (2005). Risk factors and individual probabilities of melanoma for whites. J Clin Oncol 23(12), 2669–2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu YP, Kohlmann W, Curtin K, Yu Z, Hanson HA, Hashibe M, Parsons BG et al. (2017). Melanoma risk assessment based on relatives’ age at diagnosis. Cancer Causes Control [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2018). Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Jama 319(11), 1134–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glenn BA, Chen KL, Chang LC, Lin T, and Bastani R (2016). Skin examination practices among melanoma survivors and their children. Journal of Cancer Education, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Aspinwall LG, Leaf SL, Dola ER, Kohlmann W, and Leachman SA (2008). CDKN2A/p16 genetic test reporting improves early detection intentions and practices in high-risk melanoma families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17(6), 1510–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miles MB, Huberman AM, and Saldaña J (2013). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook 3rd Aufl. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 18.University of Utah Health. (2017). Mole Mapping: Diagnose Melanoma and Skin Cancer Early: Dermatology Services, University of Utah Health. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skin Cancer Foundation. (2018). Early Detection and Self Exams: Skin Cancer Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasparian NA, Branstrom R, Chang YM, Affleck P, Aspinwall LG, Tibben A, Azizi E et al. (2012). Skin examination behavior: the role of melanoma history, skin type, psychosocial factors, and region of residence in determining clinical and self-conducted skin examination. Arch Dermatol 148(10), 1142–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aspinwall LG, Taber JM, Leaf SL, Kohlmann W, and Leachman SA (2013). Melanoma genetic counseling and test reporting improve screening adherence among unaffected carriers 2 years later. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22(10), 1687–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrera C, Scope A, Dusza SW, Argenziano G, Nazzaro G, Phan A, Tromme I, Rubegni P, Malvehy J, and Puig S. J. J. o. t. A. A. o. D. (2018). Clinical and dermoscopic characterization of pediatric and adolescent melanomas: Multicenter study of 52 cases 78(2), 278–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordoro KM, Gupta D, Frieden IJ, McCalmont T, and Kashani-Sabet M. J. J. o. t. A. A. o. D. (2013). Pediatric melanoma: results of a large cohort study and proposal for modified ABCD detection criteria for children 68(6), 913–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.State Cancer Profiles. (2018). National Institutes of Health https://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/index.html. Accessed 10/3/2018.

- 25.Manne S, Fasanella N, Connors J, Floyd B, Wang H, and Lessin S (2004). Sun protection and skin surveillance practices among relatives of patients with malignant melanoma: prevalence and predictors. Preventive medicine 39(1), 36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]