Abstract

Background

Adolescent medicine (AM) has been increasingly recognized as critically important to the health of individuals during their transition to adulthood. On a global scale, AM is often underprioritized and underfunded. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), education and AM training is developing, and AM physicians often are from general medicine backgrounds.

Objective

The objective of our scoping review was to identify existing training curricula and educational tools designed to teach AM skills to health care workers in LMICs.

Methods

We followed PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews for article identification and inclusion. Online databases, including MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and Scopus, were used to identify papers. We included studies that took place in a LMIC, were available in English, and described any of the following: published educational curricula in AM, education-based intervention for HCWs that focused on AM, or a training opportunity in AM located in a LMIC.

Results

Our review includes 14 publications: 5 published curricula and 9 articles describing educational interventions or training opportunities in AM in LMICs. Curricula were relatively consistent in the topics included, although they varied in implementation and teaching strategies. The scholarly articles described educational materials and identified a number of innovative strategies for training programs.

Conclusions

Our review found existing high-quality AM curricula designed for LMICs. However, there is limited published data on their implementation and utilization. There is a continued need for funding and implementation of education in AM in resource-constrained settings.

Introduction

Globally, adolescent medicine (AM) is increasingly recognized as critical to promoting health for adolescents, in part due to the high burden of communicable disease, high risk of accidental death, and risky pregnancy in this age group.1–3 Behaviors that begin in adolescence, such as tobacco use, drug abuse, physical inactivity, and unsafe sexual practices, are linked to almost two-thirds of premature deaths and one-third of the total disease burden in adulthood.1–3 Adolescents are susceptible to inherent risks, and many face private struggles with few places to turn for support. Whereas specialized courses in AM remain rare across the globe, health care professionals in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) can be trained in the nuances of AM and can enhance access to care for adolescents. Assuring that health care professionals receive an education in adolescent medicine is a priority to guide adolescents into healthy decision-making and help them develop into productive and fullfilled adults.

Key players in global health have issued calls to promote adolescent health in LMICs.2–5 This is increasingly important as the proportion of adolescents grows. Public health interventions including immunizations, improvement in primary care, and provision of safe water in LMICs have improved survival for children under 5 years of age, with under-5 mortality decreasing by 56% from 1990–2016,6 and we are now facing the largest population of adolescents in history.3 In 2012, adolescents comprised a quarter of the world's population, and 90% lived in a LMIC.7 These demographics come with challenges to health care provision, as growth in the health care sector does not match the rate of growth in the population of young adults. Additionally, adolescent health may be perceived as less essential in some clinical settings, as this group may be seen as physically “healthy.” In many countries, children over the age of 11 or 12 are routinely considered adults from a health care perspective; however, adolescents have specific health care needs including harm reduction, contraception, prevention of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), addiction, and mental health.8 Unfortunately, many health professionals may not feel comfortable providing care to adolescents, and they may not have received training in developmentally appropriate adolescent-friendly services.5,8 From 2002–2015, only 2.2% of aid dollars were directed toward adolescent health, reflecting the lack of attention adolescents have received in global health.9

While there have been attempts to promote adolescent-friendly health care services and improve services for adolescents, education in adolescent medicine is a largely unmet challenge in countries with limited resources. While there are formal training programs in the Americas, Europe, and Australia, there are few formal training opportunities in LMICs.10 The experience of the authors is that the AM curriculum is limited in graduate medical education settings with limited resources, particularly on the African continent. The objective of this scoping review was to identify existing training curricula and/or educational tools designed to teach AM to health care providers in limited resource settings.

Methods

To conduct the review and analysis, we followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Guidelines.11 A scoping review is similar to a systematic review in its rigor and approach. In addition, a scoping review is designed to cast a wider search net and include a broader range of articles.11

Data Sources

A medical librarian created the literature search strategy after meeting with a member of the research team to clarify goals and further define selection criteria. The search strategy was built and tested for sensitivity in Ovid MEDLINE using Medical subject headings and keywords (provided as online supplemental material), and the search strategy was translated to 3 other databases: Embase, CINAHL, and Scopus. These databases were chosen to be inclusive of international medical literature. The searches were run October 27–30, 2018.

Study Selection

Studies were included if they met these criteria: (1) described an education-based intervention or program for health professionals caring for adolescent patients; or (2) described an educational curriculum or training opportunity for health professionals caring primarily for adolescent patients; and (3) took place in a LMIC as classified by the World Bank for fiscal year 2019.12 Studies were excluded if they (1) took place in an upper-middle-income or high-income country; (2) were not available in English; or (3) were determined to be irrelevant on review of full text. Duplicate references were removed and items were uploaded to an online qualitative data software analysis program (Rayyan13) for independent review by 2 authors (K.K.M. and S.J.B.). Rayyan is a user-friendly tool that allows multiple team members to classify articles in a “blind” mode, and subsequently reveal consensus and conflicts. After initial screening, there were 17 studies with assignment conflicts; screeners then met to discuss and reach consensus. If consensus was not reached based on abstracts and titles, articles were included in the full-text review for a subsequent decision. The references of eligible articles were also reviewed by hand to identify additional articles for inclusion. Hand searching identified 5 additional articles of interest that were not captured by the database search.

Data Abstraction

We reviewed articles for study design, setting, and relevancy to our goals. Articles were categorized into 3 groups: (1) published curricula and training materials, including documents published by the World Health Organization (WHO); (2) scholarly articles describing educational curricula or interventions; and (3) articles that discussed training opportunities in adolescent medicine in LMICs.

Our goal with this scoping review was to identify as many existing curricula and interventions as possible. We did not assess study quality and included all identified studies that met eligibility criteria.

This research was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval as it consisted of a literature review and involved no patient data or patient interaction.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

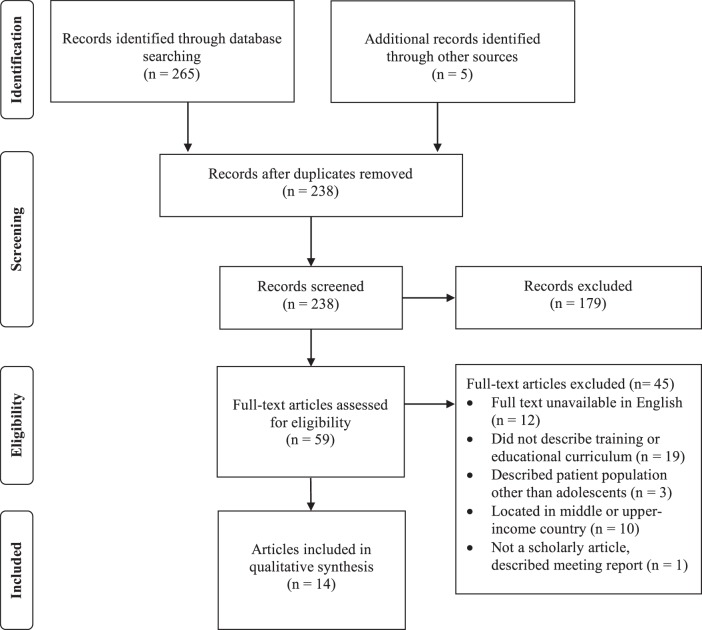

After duplicates were removed, we identified 238 citations from the electronic database search and hand-searching methods. Based on the titles and abstracts, 179 citations were excluded from the review. PDFs of 59 publications were uploaded to Rayyan for full-text review, and 45 of these did not meet the inclusion criteria (12 were excluded because they were not available in English).

Included studies were reviewed by the authors and categorized into 1 of the 3 categories above. We summarized studies and identified key points identified for inclusion in our review.

Results

The 14 articles included in the scoping review were divided into 3 categories: (1) published curricula and training materials including documents published by WHO; (2) scholarly articles describing educational and training interventions in adolescent health provision; and (3) articles describing formal training (such as post-doc or fellowship) in resource-limited settings (see the Figure).

Figure.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Published Curricula and Training Materials

A summary of the content of each published curriculum is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Published Curricula in Adolescent Medicine

| Curriculum Resource | Content Topics | Other Comments |

| A Framework for the Integration of Adolescent Health and Development Concepts Into Pre-service Health Professional Educational Curricula WHO Western Pacific Region, 2001 |

|

Divided into 4 domains, each of which have subcompetencies |

| Adolescent Job Aid: A Handy Desk Reference Tool for Primary Level Health Workers, World Health Organization, 2010 |

|

Organized into 3 sections: (1) communication/rapport; (2) chief complaint; and (3) health promotion information to share with patients and families |

| Adolescent Friendly Health Services, WHO, 2002 |

|

This publication was a “call to change” in the provision of adolescent-friendly services, with most of the content focused on how to best deliver developmentally appropriate care. |

| Orientation Programme on Adolescent Health for Health-care Providers: Facilitator Guide, World Health Organization, 2014 | Core modules

|

Part I of the module describes the process of planning and facilitating a training program, while Part II consists of the modules and program content. |

| EuTEACH: European training in effective adolescent care and health |

|

Additional themes are available online. These modules are not specifically designed for low-resource settings, but may be adapted or selectively utilized for specific situations. |

A Framework for the Integration of Adolescent Health and Development Concepts Into Pre-service Health Professional Educational Curricula, World Health Organization Western Pacific Region14:

This framework focuses on AM training in the WHO Western Pacific Region. It includes a literature review and general information about the countries in this region regarding existing adolescent health policies and programs, and establishes a list of 30 AM core competencies and 37 subcompetencies in 4 domains: professional development, psychosocial and physiological well-being, healthy behaviors and lifestyles, and sexuality and reproductive health. They are further described in Table 1.

It also proposes a framework and process for curricular integration with an emphasis on added training for nurses, midwives, midlevel practitioners, and physicians.

While a helpful document, its biggest limitation is that it is quickly becoming outdated. Additionally, at 53 pages, it lacks sufficient details for adequate implementation of the curriculum content. Key strengths are its recommendations for content and teaching methodology, and strategic approach to implementing institutional change.

Adolescent Job Aid: A Handy Desk Reference Tool for Primary Level Health Workers, World Health Organization15:

Designed as a reference guide for all types of health workers, this guide includes an algorithmic approach to case management of common adolescent complaints. Notably, the guide complements other WHO guidelines, including guidelines on pregnancy and adolescent and adult illness. The first part pays particular focus to communication and rapport with adolescent patients, including how to approach a psychosocial interview, and how to promote adolescent confidentiality. There is a discussion describing how to respond to a patient when laws prevent the health care worker from doing what is in the patient's best interest (such as providing birth control to unmarried patients). The second part encompasses algorithmic responses to common chief complaints, with details on the necessary history and physical, treatment options, and patient counseling. The third part describes information to be provided to patients, including anticipatory guidance and information regarding health promotion.

This book is a high-quality resource and a very useful tool for health care workers, as the algorithmic approach allows it to be used for chief complaints with treatments suitable for low-resource settings. Its emphasis on communication, developing rapport, and health promotion is well-executed and also appropriately tailored to low-resource settings.

Adolescent Friendly Health Services, WHO16:

This early WHO publication emphasizes the importance of adolescent-friendly health services. It focuses on the definition and implementation of adolescent-friendly services, including an emphasis on accessible, acceptable, and appropriate interventions. While it is not an inclusive curriculum and does not address clinical treatment of problems adolescents face, this publication contains valuable information on how to work with adolescents, particularly respectful and developmentally appropriate communication in health care settings.

Orientation Programme on Adolescent Health for Health Care Providers: Facilitator Guide, WHO17:

This is a detailed reference and teaching manual for health care providers (nurses, clinical officers, and physicians) in AM. The orientation program is intended to be implemented in workshops as an interactive teaching program, and the facilitator guide provides information on teaching and planning for the program. The publication includes complementary handouts for users with in-depth articles and learning activities. The facilitator guide is comprehensive, with sections on designing a workshop, key teaching methods, guidelines for inviting participants and contributors, and evaluation methods. Several core modules are suggested, including the implications of adolescent health for public health, adolescents sexual and reproductive health, adolescent-friendly health services, and adolescent development. Additionally optional modules include STIs, abortion, substance use, mental health, nutrition, chronic diseases, and injuries/violence in adolescents.

This is a comprehensive outline for creating a training program in AM. A strength is the emphasis on teaching strategies and details regarding planning a workshop. Additionally, the optional modules allow this content to be adapted for local needs.

EuTEACH: European Training in Effective Adolescent Care and Health18:

This is a series of teaching modules available at no cost from the EuTEACH website. The modules are provided as learning objectives combined with teaching strategies, and PowerPoint slides are available for downloading. The 25 modules cover a wide variety of material, including sexual and reproductive health, adolescent development, chronic disease, and more. Modules are not specifically designed for low-resource settings; however, European LMICs included in EuTEACH's domain makes this eligible for inclusion in the review. The modules provide more depth and can serve as an additional resource, and could be selectively chosen or adapted for low-resource settings.

Scholarly Articles Describing Educational Interventions and/or Training in Adolescent Health Care Provision

Seven articles were identified in this category, ranging from small qualitative studies to national curriculum implementation. These are summarized below and described in detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptions of Educational Programs and Interventions for Adolescent Health Care Providers

| Author/Year | Title | Location | Curriculum or Intervention |

| Chatterjee et al, 2009 | Recommendations on curriculum on adolescent health for undergraduate and postgraduate medical education | India | A proposed national curriculum for medical education which describes specific topics and skill sets, and a detailed plan for implementing them into national medical education. Helpfully, it suggests which departments are responsible for certain skills (such as adolescent growth and development being the domain of pediatrics, menstruation and menstrual problems the domain of obstetrics and gynecology, and preventive and promotive medicine, the domain of community medicine), and which semesters the content should fall in. It also describes specific skills, including the psychosocial interview, communication skills with adolescents, gynecological examinations, and physical examination of a victim of sexual assault. |

| Diale and Roos, 2000 | Perceptions of sexually transmitted diseases among teenagers | South Africa | This was a qualitative study that explored community nurses' perceptions of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and provided guidelines for community nurses to help youth prevent STDs. It emphasizes training in interpersonal skills for community nurses to allow for better provision of adolescent care. |

| Graeff-Martins et al, 2008 | Diffusion of efficacious interventions for children and adolescents with mental health problems | Worldwide, focus on “developing nations” | This is an extensive review of evidence-based interventions for mental health promotion. It describes 3 strategies to enhance diffusion of useful information to low-resource countries with several examples, in addition to the description of strategies implemented in high-resource countries. |

| Haslegrave and Olatunbosun, 2003 | Incorporating sexual and reproductive health care in medical curricula in developing countries | Worldwide, focus on “developing countries” | This article describes the methodology for curriculum development of a model curriculum on sexual and reproductive health targeted for continuing medical education, specifically designed for developing countries. |

| O'Malley et al, 2015 | “If I Take My Medicine, I Will Be Strong:” Evaluation of a Pediatric HIV Disclosure Intervention in Namibia | Namibia | This article describes an educational intervention to support health care workers and caregivers in the process of HIV disclosure for HIV-infected children. Tools included a staged disclosure cartoon book, readiness assessment tools, monitoring form to track progress over visits, and a training curriculum. The intervention's use of a simple disclosure book was effective and acceptable to the health care workers involved in the training, suggesting that similar strategies could be used for other topics as well. |

| Wilson et al, 2017 | Simulated patient encounters to improve adolescent retention in HIV care in Kenya; study protocol of a stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial | Kenya | This article describes an ongoing intervention utilizing standardized patients to train health care workers in empathy, communication, and assessment while working with adolescent patients with HIV. It is an innovative project and has a series of 7 scripts that standardized patients utilize for teaching. This project has not yet reached completion, but if successful, could serve as a model for similar projects in other resource-limited settings. |

| Yolsal et al, 2004 | Courses for Medical Residents and Trainers in Turkey for Promotion of Quality of Reproductive Health Services: A Pilot Study | Turkey | “Master trainers” conducted 4 courses for 67 institutional trainers, who all went on to teach 3-day programs in their own institutions. |

The scholarly articles included in the review described a number of innovative strategies for implementation of training in AM medicine. Two papers—Graeff-Martin et al19 and Haslegrave et al20—described a philosophical and strategic approach to development and implementation of training programs in AM. Two articles described stand-alone training programs in AM in China,21,22 and a third described implementation into national curriculum in India.23

Two additional articles described qualitative research performed in Africa that discussed the role of training health care workers in AM. Diale and Roos24 described a qualitative study that found that condescending and negative provider attitudes were a serious barrier to care for adolescents with STIs; they laid out steps for educating community nurses in communication. O'Malley et al25 explained an innovative study utilizing picture books and cartoons for disclosure of HIV status to HIV-infected children. This strategy strengthened the confidence of health care workers and decreased barriers to disclosure. The strategy that could be expanded for other health conditions, and has the potential to be a helpful tool in teaching young adults about their own health care.

Wilson et al26 published a promising study describing the development of simulated patient encounters in HIV care in Kenya. Simulated patient encounters are heavily utilized in AM in the high-resource settings, as they are an excellent method of teaching communication skills and humanism, subjects at the heart of AM. In particular, the psychosocial interview requires practice and modeling, a situation ripe for the utilization of simulated patients to hone these skills. The disadvantage of the use of simulated patient encounters is the high cost and heavy supervision required from advanced practitioners. However, if the study in Kenya is found to be feasible, it would serve as an excellent model for dissemination of this strategy in LMICs.

Descriptions of Available Formal Training Programs (Such as Post-Doc or Fellowship) in LMICs

This review article by Golub et al describes existing training opportunities in AM around the world. While the majority are located in wealthy nations, the authors identified training opportunities in several LMICs. These include fellowships in Latin America (although the majority are in countries classified as upper-middle income), Uganda (the only training opportunity identified on the African continent), an adolescent health workshop offered annually in Jamaica and Barbados, a fellowship in Thailand, and 2 national annual conferences in China.

A review article by Gaete27 describes training opportunities in AM in Spanish- and Portuguese- speaking countries in South America. Brazil, Chile, and Argentina have made sustained efforts to develop the field of AM and have formal training programs with robust organization. The review also includes formal training programs in Peru and Venezuela.

Discussion

We were able to identify several high-quality, free, and readily available curricula for implementing AM training programs in resource-limited settings. These were primarily created by the WHO. Among the available training programs and curricula, the content was comparable. The majority of curricula included adolescent development, approach to the psychosocial interview, adolescent friendly health care, sexual and reproductive health, confidentiality, sexually transmitted diseases, chronic disease, and HIV.

Despite the identification of high-quality AM curricula, the number of articles describing implementation of AM training programs and curricula was limited. This suggests that, while high-quality curricula are available, they are not widely utilized. The paucity of education-based interventions targeting providers who care for adolescents is concerning when compared to interventions targeting those caring for neonates or younger children. This is consistent with previous literature identifying a lack of funding for interventions targeting adolescents compared to other age groups.9 Our findings demonstrate the continued need for prioritization and funding of projects promoting the health of adolescents.

Among the curricula, training programs, and interventions identified, the most interesting and important finding of our scoping review could be the identification of topics that were omitted. While sexual and reproductive health, adolescent-friendly health care services, and HIV care have been covered in reasonable detail, there is a relative under-emphasis on mental health, substance use and addiction, care of adolescents with chronic disease, transitioning care to adult providers, and the health care of sexual minority youth. These represent important health concerns for adolescents worldwide,4 and we identified a critical absence of these topics in the existing literature. The paucity of programs in transitioning care and management of chronic diseases may reflect the historically lower survival rates of chronically ill adolescents. However, as we have developed effective and life-prolonging treatments for conditions such as HIV, the importance of transitioning care and working with chronically ill adolescents has become increasingly evident. There has been a growing trend worldwide of increased diagnosis of mental health concerns,28 including in adolescent populations, and this remains a largely unmet need.29 Finally, none of the studies in this review addressed sexual minority youth in any depth, likely reflecting the varying levels of cultural acceptance of same-sex relationships and gender diversity in LMICs.

Going forward, government and private programs can make a conscientious effort to include adolescent health promotion in training programs and materials. Funding priorities should reflect the current needs of adolescents, in particular sexual and reproductive health care (including sexual minority and gender diverse youth), mental health and addiction care, management of chronic diseases, and transitions to adult providers.

Our scoping review has limitations. Like all scoping reviews, we focused on including a wide variety of articles in order to identify as many eligible articles as possible and did not assess the quality of articles. Additionally, we may have missed educational interventions or curricula that were not published in the academic literature, and we did not consider publications in languages other than English language.

Conclusion

While there are existing high-quality AM curricula for limited resource settings, their implementation and utilization appears to be sparse. Some efforts to increase education in AM have been successful in a variety LMICs. Our scoping review identified the need to prioritize and fund training programs that promote education in sexual and reproductive health, management of chronic illness, mental health and addiction care, care of sexual minority youth, and transitioning care to adult services.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Gates M. Advancing the adolescent health agenda. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2358–2359. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheehan P, Sweeny K, Rasmussen B, Wils A, Friedman HS, Mahon J, et al. Building the foundations for sustainable development: a case for global investment in the capabilities of adolescents. Lancet. 2017;390(10104):1792–1806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations Population Fund. Das Gupta M, Engelman R, Levy J, Luchsinger G, Merrick T, Rosen JE. State of World Population 2014. The Power of 1,8 billion Adolescents, Youth and the Transformation of the Future. 2019 http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/EN-SWOP14-Report_FINAL-web.pdf Accessed June 21.

- 4.Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and well-being. 2018;387(10036):2423–2478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee L, Upadhya K, Matson P, Adger H, Trent ME. The status of adolescent medicine: building a global adolescent workforce. Int J Adolesc Med Heal. 2017;28(3):233–243. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2016-5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics. 2014. apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112738/1/9789240692671_eng.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2019.

- 7.Salam RA, Das JK, Lassi ZS, Bhutta ZA. Adolescent health and well-being: background and methodology for review of potential interventions. J Adolesc Heal. 2016;59(2):S4–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Adolescent Friendly Health Services: An Agenda for Change. 20012019 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67923 Accessed June 21.

- 9.Li Z, Li M, Patton GC, Lu C. Global development assistance for adolescent health from 2003 to 2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181072. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golub SA, Arunakul J, Hassan A. A global perspective: training opportunities in adolescent medicine for healthcare professionals. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28(4):447–453. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2019 https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups Accessed June 21.

- 13.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. A Framework for the Integration of Adolescent Health and Development Concepts Into Pre-Service Health Professional Educational Curricula WHO Western Pacific Region. 20012019 http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/docs/ADHframework.pdf Accessed June 21.

- 15.World Health Organization. Adolescent Job Aid: A Handy Desk Reference Tool for Primary Level Health Workers. 20102019 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44387 Accessed June 21.

- 16.World Health Organization. Adolescent Friendly Health Services An Agenda for Change Adolescent Friendly Health Services—An Agenda for Change. 20032019 https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67923 Accessed June 21.

- 17.World Health Organization. Orientation Programme on Adolescent Health for Health-Care Providers: Facilitator Guide. 20142019 https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9241591269/en/ Accessed June 21.

- 18.European Training in Effective Adolescent Care and Health. EuTEACH Modules. 2019 https://www.unil.ch/euteach/en/home.html Accessed June 21.

- 19.Graeff-Martins AS, Flament MF, Fayyad J, Tyano S, Jensen P, Rohde LA. Diffusion of efficacious interventions for children and adolescents with mental health problems. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2008;49(3):335–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haslegrave M, Olatunbosun O. Incorporating sexual and reproductive health care in the medical curriculum in developing countries. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11(21):49–58. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee RL, Hayter M. The effect of a structured adolescent health summer programme: a quasi-experimental intervention. Int Nurs Rev. 2014;61(1):64–72. doi: 10.1111/inr.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee RLT, Wang JJ. Effectiveness of an adolescent healthcare training programme for enhancing paediatric nurses' competencies. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(21):3300–3310. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatterjee S. Recommendations on curriculum on adolescent health for UG and PG medical education, 2009. Indian J Public Health. 2009;53(2):115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diale DM, Roos SD. Perceptions of sexually transmitted diseases among teenagers. Curationis. 2000;23(4):136–141. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v23i4.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Malley G, Beima-Sofie K, Feris L, Shepard-Perry M, Hamunime N, John-Stewart G, et al. If I take my medicine, I will be strong: evaluation of a pediatric HIV disclosure intervention in Namibia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(1):e1–e7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson KS, Mugo C, Bukusi D, Inwani I, Wagner AD, Moraa H, et al. Simulated patient encounters to improve adolescent retention in HIV care in Kenya: study protocol of a stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):619. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2266-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaete V. Adolescent health in South America. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;28(3):297–301. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2016-5013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. World Health Organization Report—Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. 2019 https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf Accessed June 21.

- 29.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18(1):23–33. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.