Abstract

We present a vision for improving household financial surveys by integrating responses from questionnaires more completely with financial statements and combining them with payments data from diaries. Integrated household financial accounts—balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows—are used to assess the degree of integration in leading U.S. household surveys, focusing on inconsistencies in measures of the change in cash. Diaries of consumer payment choice can improve dynamic integration. Using payments data, we construct a statement of liquidity flows: a detailed analysis of currency, checking accounts, prepaid cards, credit cards, and other payment instruments, consistent with conventional cash-flows measures and the other financial accounts.

JEL Classifications: D12, D14, E41, E42

Keywords: Surveys, diaries, payments, financial statements, cash flows

1. Introduction

During recent decades, interest in the study of household finance has grown rapidly. Campbell (2006) first advanced the case for treating household finance as a distinct field of study in economics. The global Financial Crisis of 2008–09 strengthened that case due to the subprime housing debacle in many industrial economies and its persistent impact on household balance sheets. In particular, the extent and nature of increased leverage and risk in household mortgages and their effects on the real (housing industry) and financial (shadow banking) sectors of the economy were not well known or understood prior to the crisis. Consequently, there is now a focus on household decisionmaking, how households got into this trouble, what transpired in the crisis, and the difficulties encountered thereafter.1

A hindrance to research and understanding of household economic behavior (real and financial) has been the lack of sufficient data. Relative to other countries, the United States has a large amount of high-quality data on household economic behavior; these data will be examined closely in this paper. Even the U.S. data, however, were inadequate to inform economic agents and policymakers sufficiently to avoid the Financial Crisis. Many efforts are underway to acquire and develop additional needed data; these efforts include the Eurosystem’s Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS), which was inspired partly by the U.S. Survey of Consumer Finances.2 Other efforts, such as the National Academy of Science’s call for a substantially revised Consumer Expenditure Survey, aim to reform existing datasets (Dillman and House 2013).

U.S. household survey data exhibit several characteristics that limit their effectiveness. The U.S. statistical system (public and private) is decentralized, with each data source specializing in a part of household activity. Although there are often good reasons for specialization, the result is a general lack of comprehensive measurement of household activity. Many datasets are cross-sectional, which limits their ability to track the behavior of specific households over time, and are gathered infrequently. When data sources are combined in an effort to provide a more comprehensive view of household behavior, the combination of the specialized data sources can create imperfect, if not misleading, views of household economic conditions, due to differences in sampling, measurement, and linkages between microeconomic and aggregate data.3 These imperfections make it difficult to ascertain from the data the extent and nature of important developments, such as adjustments affecting household balance sheets in the wake of Financial Crisis, increases in income inequality, and intergenerational dynamics of household net worth.

Data on household behavior in other countries also exhibit limitations, but there are signs of improvement in response to major economic developments. Most notably, the Financial Crisis reaffirmed the view that household finance is at the center of development economics because financial access is thought to be one of the key factors that could help poor and vulnerable households become more productive and resilient in the face of economic shocks. In addition, there have been payment innovations such as M-Pesa in Kenya, an electronic money issued by a cell phone company, Safaricom, that in many respects is now on par with currency there as a medium of exchange (Jack, Suri, and Townsend 2010). The often-expressed hope in developing economies is that a deeper, more developed financial system can be built on top of such an improved payments system, with some progress evident in countries such as Pakistan.4 These developments bring us back to the need for better data on payments, household behavior, and a micro-founded view of the macro economy in developing countries. Fortunately, more countries are producing data from household surveys that are doing a better job of measuring these developments.

We believe an important step forward in understanding household behavior is the development of more reliable and effective measures of household economic activity, both real and financial. Therefore, an overarching goal of this paper is to describe a comprehensive vision for practical implementation of household surveys that are integrated with financial statements and payments data, leaving no gaps in measurement and strengthening the theoretical and applied linkages among measures. The main contributions of this paper are: 1) to assess how well integrated U.S. household surveys are with elements of financial statements for households; and 2) to demonstrate how a diary of U.S. consumer payment choices can be used to construct a new statement of liquidity flows that advances the current state of the art in measuring stock-flow dynamics and thus takes a step closer to realizing the overarching vision of the paper.

Samphantharak and Townsend (2010, henceforth ST) describes the baseline conceptual framework for the design of an integrated survey that has been implemented in the field for almost 20 years and that allows construction of a complete set of household financial statements that is comprehensive and fully integrated. Essentially, ST creates a set of financial accounts akin to those of corporate firms: this set comprises a balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows. The concept is of a household with projects, that is, a collection of assets that earn income from farm and non-farm production activities. This idea of assets earning income also extends to households engaged in wage or salaried labor, meaning those that essentially generate income from their human capital. A key element of this analysis is that all aspects of household situations and behaviors are measured: income, in order to measure the productivity of physical and human capital; assets and liabilities, to measure wealth; and cash flow, to distinguish liquidity from income and profitability. A key to this measurement is that the accounts are required, by construction, to be consistent with one another, thereby eliminating the possibility of gaps. Few surveys feature this dynamic integration.

To illustrate how this works, and as a first step in the paper, we use the ST framework to assess the degree of integration in leading U.S. household surveys. For each survey considered, we tabulate and juxtapose the data of each in the form of corporate financial statements applied to the representative U.S. household. We first construct for each survey a harmonized balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows for a recent time period that matches the survey dates—around 2012—as closely as possible. To ensure maximum accuracy, we have invited assistance from representatives associated with each survey; and to encourage further refinement of this effort, we make our programs available to interested researchers. Then, we use the estimated U.S. household financial statements to characterize the degree of integration by two distinct measures. Integration by coverage reflects the extent to which a survey contains estimates of each line item in the financial statements. All the surveys cover roughly half the income statement items, although most specialize in income or expenditures. However, the coverage of the balance-sheet items varies widely across surveys. Integration by dynamics reflects the extent to which the statement of cash flows accurately measures the law of motion between stocks (shown in the balance sheet) and flows (shown in the income statement). None of the surveys can provide truly direct statements of cash flows, and all of them make large errors relative to indirect estimates of changes in assets and liabilities.

Our assessment of integration in U.S. household surveys is merely a factual statement of results and is not intended to be a criticism of the surveys or a call for reforming them. We recognize and accept the specialty nature of U.S. surveys, which has the benefit of allowing gains from specialization and achievement of each survey’s original goals. For example, the Panel Study on Income Dynamics (PSID) was originally designed to measure poverty and to contribute to its reduction in conjunction with President Johnson’s Great Society programs; the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) was designed to gather data for developing accurate price indices; and the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) to measure wealth. Although some of these surveys have evolved over the years, particularly the PSID, others retain their original mandate. Yet the specialization and persistence of the U.S. surveys does leave gaps in measurement that can only be overcome by comprehensive integration of the surveys with financial statements. Ironically, because the PSID and SCF are so highly regarded, they are adopted as the gold standard elsewhere in the world, for example, in China and Europe, thus propagating essentially the same gaps in these other surveys as in their U.S. counterparts.

A second step of this paper is to use the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s 2012 Diary of Consumer Payment Choice (DCPC) to demonstrate how consumer payment diary surveys can improve the dynamic integration of surveys.5 The DCPC directly measures several, but not all, components of the law of motion governing the stock-flow relationship between assets and liabilities (balance-sheet items) and income and expenditures (income-statement items). Because the 2012 DCPC is focused on consumer payments authorized by payment instruments (cash, check, debit or credit card, online banking, and such), it focuses on liquid assets used as payment instruments, including the currency held and used by U.S. consumers. In this respect, the DCPC is similar to the Townsend Thai Monthly Survey (TTMS), which underlies the ST methodology, where currency is the main household asset and payment instrument in rural Thailand. To provide a bridge to our key next step, we compare and contrast the household financial statements constructed with TTMS with those constructed with the DCPC.

The central innovation of this paper is the construction of a new, more detailed analysis of cash flows at the level of liquid asset accounts, where currency, checking accounts, and other liquid assets are distinguished and treated separately. By tracking consumer expenditures that are authorized by payment instruments tied to specific types of liquid asset accounts, the DCPC matches expenditures to the sources of money and credit that fund them. This matching cannot be done feasibly by surveys that track consumer expenditures at the level of individual products (the Consumer Expenditure Survey) or at the level of aggregated expenditure categories (“food away from home”).

Linking all the liquidity accounts to one another and to the expenditures (or investments) they fund makes it possible to better assess the changing landscape of payments taking place in the United States and industrialized countries as well as in emerging-market and low-income countries.6 This then links back to the need for data to better inform public policy and to provide consumers with the information they need to improve household decisionmaking and economic behavior. More informative financial accounts come from considering payments, and vice versa: better payments data come from integrated financial accounts. Development of household economic data from dynamically integrated household surveys that include payment diaries might be particularly beneficial for developing countries, where household economic data are scarce, there are few pre-established surveys with prior missions, and payment systems and financial industries are changing rapidly. Of course, payments systems are also changing in the United States. The 2015 DCPC took a small step toward integrating payments and employing the ST framework, as described below. We provide a framework and guidance for policymakers to implement this longer-run vision.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the main U.S. household surveys. Section 3 reviews the ST methodology and explains how it will be used in our analyses. Section 4 assesses the degrees of integration in U.S. household surveys, by coverage and dynamics. Section 5 compares and contrasts the TTMS and DCPC survey data. Section 6 describes the innovation made possible by the interaction of ST’s methods with the DCPC. Section 7 concludes.

2. Overview of U.S. Household Surveys

This section describes the main surveys included in this study, which are used to collect data on U.S. household economic conditions (henceforth, “household surveys”), plus the TTMS. Summary descriptions of these surveys appear in Table 1 in order of chronology based on continuous fielding. Five sponsors produce these U.S. surveys:

TABLE 1.

Overview of U.S. Surveys and Diaries and TTMS

| PSID | CE-S/D | SCF | SIPP | HRS/CAMS | S/D-CPC | TTMS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sponsor | University of Michigan | BLS | Federal Reserve Board | Census Bureau | University of Michigan | Boston Fed | MIT |

| Vendor | University of Michigan | Census Bureau | NORC/University of Chicago | Census Bureau | University of Michigan | RAND/University of Southern California | Thai Family Research Project |

| Frequency | Biennial | Monthly | Triennial | Quarterly | Biennial | Yearly/irregular | Monthly |

| Period | 1968-present | 1980-present | 1983:Q1-present | 1983:Q4-present | 2008-present | 2012, 2015 | 1998-present |

| Statistical Calculations | 2011, 2013 | 2011, 2012 | 2009, 2012 | 2010, 2011 | 2010, 2012 | 2011, 2012 | 2012 |

| Questionnaires | |||||||

| Observation unit | U.S. Family unit | U.S. Consumer units | U.S. Primary economic units | U.S Households | U.S. Households | U.S. Consumers and households | Thai Households |

| Mode(s) | Interview | Interview, diary | Interview | Interview | Interview, mail | Interview, diary | Interview |

| Data collection | Recall | Recording, recall | Recall | Recall | Recall | Recording (1 day), recall (1 year) | Recall |

| Measurement period | Past year | Daily expenditures (diary), or past year (survey) | “Average” week for expenditures, past year for income | Past month, past 4 months, or past year | Past year | Daily payments (DCPC), or “typical” week, month, year (SCPC) | Past month |

| Sampling | |||||||

| Target Population | Total U.S. Non-institutional | Total U.S. Non-institutional | Total U.S. Non-institutional | Total U.S. | U.S. ages 50+ Non-institutional | Age 18+ Non-institutional | Rural and Semi-Urban Households |

| Sampling Frame | Survey Research Center National Sampling Frame | U.S. Census Bureau Master Address File | NORC National Sampling Frame and IRS data | U.S. Census Bureau Master Address File | Panel of adults born 1931–1941 | RAND ALP, USC UAS, GfK Knowledge Networks | Initial Village Census |

| Sample size | ~10,000 | ~7,000 | ~6,000 | 14,000–52,000 | 9,000–15,000 | ~2,000 | ~800 |

| Longitudinal panel | 4 consecutive quarters | 14 days | None | 2.5–4 years | Fixed | 3-day waves tied to SCPC annual panel | 1998-present |

HRS/CAMS:https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/about

University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research (ISIR) – The Michigan ISIR sponsors two surveys. First, the biennial Panel Study on Income Dynamics (PSID), which is “the longest running longitudinal household survey in the world” and that includes data on wealth and expenditures as well as other socio-economic and health factors.7 Second, the biennial (even-numbered years) Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), which “has been a leading source for information on the health and well-being of adults over age 50 in the United States” for more than 20 years; the HRS includes the biennial Consumption and Activities Mail Survey (CAMS) for tracking household expenditures in “off” years (odd-numbered).8

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) – The BLS sponsors the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE), comprising “two surveys—the quarterly Interview Survey and the Diary Survey—that provide information on the buying habits of American consumers, including data on their expenditures, income, and consumer unit (families and single consumers) characteristics.”9 “As in the past, the regular revision of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) remains a primary reason for undertaking the Bureau’s extensive Consumer Expenditure Survey. Results of the CE are used to select new ‘market baskets’ of goods and services for the index, to determine the relative importance of components, and to derive cost weights for the market baskets.”

Federal Reserve Board – The Board sponsors the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), “normally a triennial cross-sectional survey of U.S. families. The survey data include information on families’ balance sheets, pensions, income, and demographic characteristics. Information is also included from related surveys of pension providers and the earlier such surveys conducted by the Federal Reserve Board.” The SCF collects some consumer expenditures directly.10

U.S. Census Bureau – The Census Bureau sponsors the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), “the premier source of information for income and program participation. SIPP collects data and measures change for many topics including: economic well-being, family dynamics, education, assets, health insurance, childcare, and food security.”11

Federal Reserve Bank of Boston – The Boston Fed’s Consumer Payments Research Center (CPRC) sponsors the annual Survey of Consumer Payment Choice (SCPC) and the occasional Diary of Consumer Payment Choice (DCPC), both of which measure consumer adoption of payment instruments and deposit accounts and the use of instruments. Originally, the SCPC and DCPC were not integrated like the CE but were developed independently; they are now being integrated. The SCPC collects only the number of payments, while the DCPC also tracks the dollar values. Both provide data on cash and (in later years) checking accounts plus revolving credit. The SCPC contains very limited information about household balance sheets.

These surveys were selected because of their quality and breadth of coverage of U.S. household financial conditions, including relatively large numbers of detailed questions pertaining to the line items of household financial statements (assets, liabilities, income, or expenditures). None of the surveys contains all relevant financial conditions because none was designed to do so. Thus, no single survey is fully integrated with financial accounting statements and no single survey alone can provide complete estimates of household financial conditions. When combined, however, these U.S. household estimates come closer than any single dataset available today to providing a comprehensive assessment of U.S. household financial conditions. These surveys were also chosen because, except for the HRS, they are representative of U.S. consumers. 12 However, the surveys are implemented with different samples of households (or consumers) and, in some instances, substantively different survey questions, so their estimates are not necessarily comparable.

We reiterate that each survey has its own particular purposes or goals and that none is intended to provide a comprehensive, integrated set of household financial conditions as described in ST. The CE, for example, is primarily intended to produce data on a wide range of consumption expenditures that aid in the construction of the CPI. In contrast, the SCF primarily tracks details of assets and liabilities plus income from all sources but does not track all consumer expenditures. The PSID aims to estimate most income and expenditures but also focuses on collecting data on social factors and health, a practice that might be beneficial for every survey and data source. In any case, the PSID’s breadth limits the amount of detail it can obtain on income and expenditures, so it does not obtain a comprehensive estimate of balance-sheet items. For all of these reasons, the analysis in the next section does not expect or presume to find an individual integrated financial survey, nor does it recommend that any of these surveys change what it is currently doing.

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the selected U.S. household surveys in terms of their basic features, survey methodologies, and sampling methodologies. Surveys are listed in columns in chronological order (left-to-right) based on their initial years of continuous production. The oldest is the PSID, which dates back to the 1960s, while the newest, the SCPC and DCPC, are less than a decade old. Most of the surveys are conducted relatively infrequently, ranging from quarterly (the CE and SIPP) to triennially (the SCF). Although implemented daily for one or two months, the official DCPC has been implemented only three times in five years. The date of statistical calculations refers to the period used to estimate the elements of the household financial statements, as discussed later in the paper. The rows of the table are grouped into sections related to the survey methodology and the sampling methodology. For further comparison, the table also shows corresponding information about the TTMS.

Survey methodologies vary widely across the surveys along several dimensions. One obvious distinction is the mode: survey (PSID, CE-S, SCF, HRS, SIPP, and SCPC) versus diary (CE-D, DCPC) or “diary survey.” This distinction is complicated by the fact that modes also vary for each type of survey or diary, including paper surveys, paper diaries (or memory aids), online surveys—with or without assistance—and interviews; some surveys use mixed-mode strategies. A key differentiating factor among surveys is whether they collect data based on respondents’ recall, where the recall period can vary in length from a period of one week to one year, or based on respondents’ recording the data, where the recording period is typically one day. Recall-based surveys are more susceptible to memory errors and aggregation errors (over time and variable types). Some sponsors field their own survey (Michigan ISIR), while others outsource to vendors (for example, the SCF uses NORC, formerly called the National Opinion Research Center).

The sampling methodologies are relatively similar across surveys. All surveys aim to provide estimates that are representative of some U.S. population measure, except the HRS, which is limited to older households. The main reporting unit varies across surveys from individual consumers to entire households, with some surveys obtaining information about the household from just one member—an important choice that can significantly affect the results of the survey. The surveys also differ in whether the samples are drawn as independent cross-sections or as longitudinal panels. The precision of survey estimates varies widely because sample sizes range from 2,000 to 52,000 reporting units.

Estimates of economic and financial activity for consumers and households are influenced heavily by at least two major types of factors: 1) heterogeneity in the survey specifications, sampling methodologies, and data collection methodologies; and 2) variation across surveys in the content, scope, and nature of questions about real and financial economic activity. Therefore, the reader should not expect estimates of income, expenditures, or wealth from the surveys to coincide. Instead, there might be large discrepancies in estimates of these economic and financial activities even if the conceptual measures are similar. Differences in target populations can naturally produce large differences in economic and financial measures. But even more subtle survey design differences, such as recall versus recording, can produce large differences in the estimated measures. With regard to survey content and questions, even minor differences in wording can elicit differences in measured concepts between surveys. Similarly, the level of aggregation—collecting data on just the total or on the sum of the parts of the total (and then adding them up)—can have dramatic effects on estimates of the total values across surveys.

3. The Samphantharak-Townsend Framework

This section provides a brief overview of the Samphantharak and Townsend (2010), or ST, framework for defining and measuring the integration of household surveys with corporate financial statements.

3.1. Conceptual Framework

There are three main financial statements in the ST “household as corporate finance” framework.13 The first statement is the balance sheet or the statement of financial position, which reports all assets and liabilities at a point in time. The difference between assets and liabilities is net worth. In the terminology of corporate financial accounts, net worth is the household’s equity in the household enterprise. The second financial statement is the income statement, which measures flows of revenues and expenses as well as the disposition of net profit into consumption and savings over a period of time. Finally, the statement of cash flows measures money, cash, or other liquid assets flowing into and out of the household as part of the payments system. In practice, cash flows are simply the outflows of cash for the acquisition of inputs of production, as well as for investment and consumption expenditures, and the inflows from sales of product, liquidation of assets, and financing.

The balance sheet is a stock report, while the income statement and the statement of cash flows are flow reports. There is a close connection between the balance sheet and the income statement through the connection between stocks and flows, as summarized in Figure 1. Specifically, profits from production or from salary and other income can be saved or consumed. Consumption is analogous to paying out a dividend to the owner. Positive savings show up as an increase in (real or financial) assets and wealth, reflected in the balance sheet at the end of the period. Likewise, negative savings show up as a decrease in assets and wealth. Indeed, the change in wealth in the balance sheet between two points in time is essentially net savings.14

FIGURE 1.

Relation Between Household Income Statement and Balance Sheet

Income in corporate financial statements is typically accrued income, based on the idea that expenses of production are not subtracted until revenues from sales resulting from that production are recognized.15 The essential idea behind this notion of accrued income is that one wants to measure the ultimate return on a project in order to compare that return to alternatives; that is, one wants to measure the opportunity cost in order to see whether the project is warranted, in order to answer the obvious question: do the economic activities the household has adopted “make sense”? Essentially, accrued income is supposed to measure productivity. However, since the accrual basis of accounting does not necessarily recognize revenues or expenses when cash flows in or out of the enterprise, it cannot give analysts a full understanding of the enterprise’s liquidity. For example, a project may be productive with a reasonably high rate of return, but it may become illiquid due to cash-flows fluctuations and the household may even go bankrupt. This example illustrates one of the reasons why the statement of cash flows is needed to obtain a comprehensive understanding.

To summarize, the reconciled financial statements must exhibit the following accounting identities: (1) in the balance sheet, the household’s total assets must be identical to its total liabilities plus total wealth or net worth, (2) the increase in household wealth in the balance sheet over the period must be identical to the household’s savings (adjusted for unilateral transfers); that is, it must be identical to a household’s net income from the income statement minus consumption, and (3) the increase in the household’s cash holdings in the balance sheet must be identical to the household’s net cash inflow in the statement of cash flows, summing over all sources. Both sides of every accounting identity are measured.

One benefit of imposing accounting identities is that we avoid the common problem that a variable generated from one set of questionnaire responses yields a different value when computed from an alternative set of responses. For example, Kochar (2000) finds that household savings in the Living Standard and Measurement Study (LSMS) surveys computed as ”household income minus consumption” is different from household savings computed from “change in household assets.” This discrepancy could come from various problems in questionnaire design. For example, some of the assets might be omitted from total assets, some assets might be financed by liabilities rather than savings, or income and savings might be defined inconsistently. Indeed, as mentioned above, one can use these two different measures of savings, which may differ as indicated, as a consistency check within a survey or diary fielding, with follow-up questions in the case of discrepancies.

ST applied this vision of integrated surveys to the Townsend-Thai Monthly Survey (TTMS). Transactions in the monthly data are like journal entries for an accountant, allowing the analyst to create complete financial accounts. As details of the transaction partners are also recorded, one can map networks within the village and also geographic patterns. Figure 2 illustrates the procedure for creating a household’s balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows from a panel household survey. More information about the TTMS appears in Section 5.

FIGURE 2.

Constructing Financial Statements from a Panel Household Survey

3.2. Details of the Statement of Cash Flows

Because the dynamic accounting of linkages between stocks and flows is central to this paper, we provide a more detailed discussion of this topic. The statement of cash flows (CF) provides an accounting of cash received and cash paid during a particular period of time, thereby providing an assessment of the operating, financing, and investing activities of the firm (or household).

The first step in constructing a cash-flows statement is to define the term “cash.” Despite the label, it is important to remember from the outset that currency is typically only part of this. For advanced industrial economies such as the United States, standard corporate financial statements tend to focus cash flow on the concept of “cash and cash equivalents” (CCE):

Cash – Currency (coins, notes, and bills) 16 and liquid deposits at banks and other financial institutions, including demand deposits, other checkable deposits, and savings accounts. This measure is similar to the broad measure of money known as M2.17

Cash Equivalents – Short-term investments with a maturity of three months or less that can be converted into cash quickly, easily, and inexpensively (high liquidity, low risk). None of the surveys identify cash equivalents separately from similar investments of longer maturity. Examples include 3-month Treasury bills versus 1-year Treasury bonds and 3-month versus 6-month certificates of deposit).18

The assessment of U.S. surveys will focus on CCE for the statement of cash flows. For the TTMS and DCPC, however, the statement of cash flows will focus only on currency because Thai households transact primarily in currency (Thai baht) and the 2012 DCPC is a payment diary that does not track the entire balance sheet and has only one liquid asset (currency in U.S. dollars, which is a payment instrument).19 Most U.S. surveys do not collect data on currency, which is a relatively small portion of liquidity for most U.S. households, and only the SCPC and DCPC do so comprehensively.

Once cash is defined, cash flows for that defined concept (CCE) can be calculated to account for the operating, investing, and financing activities of the firm (or household).20 In particular, the statement of CF includes three main parts:

CF from production (or operating activities) – These are net cash flows from operating activities of the firm (or household). The direct method shows cash inflows from operations and cash payments for expenses, by major classes of revenue and expense. Equivalently, the indirect method converts net income from an accrual basis to a cash basis, using changes in balance-sheet items.

CF from investing activities (consumption and investment) – These are net cash flows from investing activities of the firm (or household). Cash outflows are primarily for investment in capital and for the purchase of securities that are not CCE. Cash inflows are the converse, including sales of capital and non-CCE securities. Individual items are listed in gross amounts (inflows minus outflows), by activity. As applied to the household, these are consumption expenditures (on nondurable goods and services) and capital expenditures (on durable goods).

CF from financing – These are net cash flows from transactions considered to be the financing activity of the firm (or household). Cash inflows occur when resources are obtained from owners or investors, such as by issuance of equity or debt securities. Cash outflows are the converse, in the form of payment to owners and investors or to creditors. As with CF from investing, individual items are listed in gross amounts.

Another type of transaction sometimes associated with the statement of CF is direct exchange, which occurs when non-cash (not CCE) assets or liabilities are traded without implications for cash. Often these exchanges are difficult to classify as either investing or financing activity because they may have elements of both. For that reason, accountants do not agree on whether to include direct exchanges in the statement of CF or to report them in a separate statement. For this paper, we do not include them in statement of CF.

In theory, the statement of CF provides an exact linkage between flows in the income statement and changes in stocks on the balance sheet. To verify this, the statement of CF compares measured cash flows with the measured changes in assets and liabilities from the balance sheet. Total CF is simply the sum of component flows,

where superscript p denotes production (operating activity), v denotes investing activity, and f denotes financing activity. If all financial-statement items are measured accurately and constructed comprehensively, this estimate from the statement of CF should exactly match the change in the stock of cash from the balance sheet,

where denotes the asset value (end-of-period t) of cash and cash equivalents (superscript C). If these CF identities were to hold exactly using data from a survey, then that survey would be fully dynamically integrated with financial statements. In practice, however, measurement of financial-statement items is neither exact (due to measurement error) nor comprehensive in actual surveys (due to failure to include all items), so we expect to observe errors in the CF identities above (that is, we expect to see less-than-full dynamic integration). One logical measure of the degree to which survey estimates are integrated across time (dynamically) is

which is expressed as a percentage of lagged cash. Smaller CF errors (in absolute value) are interpreted as indicating better dynamic integration of a survey.21

This analytical linkage between cash flows (also on the income statement if the cash basis rather than the accrual basis is used) and the stock of cash (balance-sheet items) can be disaggregated into the linkages between individual liquid assets (stocks) in CCE and the gross flows among them. Henceforth, our language assumes the cash basis is used, but our analysis remains valid for the accrual basis, since the real difference between the cash and accrual bases is only the labeling of the transaction; for example, goods sold create an account receivable that is not necessarily cash and does not appear on the statement of cash flows if the latter does not recognize accounts receivable as CCE. Nevertheless, the sale would be recognized as creating an increase in an asset (an accounts receivable item).

To see the point about disaggregation, let denote the end-of-period dollar value of a liquid asset in CCE from the balance sheet, where subscript k denotes the account/type of liquid asset (currency, demand deposits, and such) and subscript t denotes the discrete time period (such as month, quarter, or year). Liabilities, Lkt, are defined analogously and primarily represent various types of loans; in principle, liabilities can be viewed as negative-valued assets.22

Let Dkdt denote the dollar value of deposits into account k on day d (nearly continuous), and Wkdt the analogous withdrawals.23 Gross cash flows in period t are the sums across all daily flows into and out of an asset type:

Asset deposits include primarily income of all types (including any capital gains and losses from holding CCE), transfers of another type of asset (or liability) into the account, or unilateral gifts received. Asset withdrawals include primarily payments for goods and services (consumption expenditures or capital goods investment), transfers to another type of asset, or unilateral gifts given. Again, liability flows are defined analogously.

Individual assets are governed by the following law of motion between periods t −1 and t:

Individual liabilities are governed by an analogous law of motion where the liability “return” is primarily interest paid.

Finally, the disaggregated cash flows for each CCE type of asset include some that net to zero when aggregated across all account k accounts. For example, if a consumer withdraws $100 in currency (k =1) from a checking account (k = 2), then D1dt = W2dt. For this reason, it is informative to track the flows among types of asset (and liability) accounts when analyzing the cash-flows behavior of households. For some types of asset accounts, such as a checking account, withdrawals can be made with multiple payment instruments, such as checks, debit cards, and various electronic bank account payments. Thus, the gross flows between accounts can be further disaggregated by the type of payment instrument used to authorize the flow.24

4. Assessment of Integration in U.S. Household Surveys

This section evaluates the content and structure of the main U.S. household surveys, excluding the SCPC and DCPC, which are not designed to be general surveys of household finance, in relation to corporate financial statements. As noted earlier, no U.S. survey is fully integrated with financial statements in a manner consistent with the ST framework. However, all of the U.S. surveys contain questions that provide estimates of many of the relevant stocks and flows in financial statements. Therefore, the ST framework can be used to organize the survey data into estimates of a representative (average) U.S. household’s financial statements: a balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows. The remainder of this section presents those estimates for each survey and analyzes the results.

The tables in this section report estimates of U.S. financial statements from the surveys. Each statement contains nominal dollar-value estimates for the line-item elements from each survey, aggregated to the U.S. average per household, with the sampling weights provided by the survey programs.25 Selected aggregate measures are supplemented with medians. The line items (rows) of each financial statement reflect our best effort to combine survey concepts into reasonably homogeneous measures.26 Where necessary and feasible, some survey concepts fall into the “other” categories; tables are footnoted extensively to clarify these details. To the extent possible, all economic concepts from each survey are included in the statements. However, the question wording and concept definitions can vary significantly across surveys, so detailed estimates fall short of perfect harmonization. To ensure proper handling, we have provided our preliminary results and software programs to managers or principal investigators of each survey and offered them the opportunity to evaluate and correct our analysis.27

Juxtaposing estimates of the financial statements for each survey provides two benefits. First, and independently of the ST methodology, the financial statements provide valuable information about the relative magnitudes of real and financial economic conditions estimated by each survey. Differences between survey estimates can be large in absolute and relative terms because of the absence of perfect harmonization, as noted above. The aggregate estimates may also diverge due to significant differences in survey or sampling methodologies, described in Section 2, or due to differences in the coverage of statement line items, described below. In any case, the comparison of estimates reveals the relative strengths and weaknesses of each survey in measuring household economic conditions.

Second, juxtaposing the estimates facilitates an easy and quantitative assessment of how well each survey’s questions integrate with the elements of the household financial statements. The degree of integration can be evaluated by at least two standards: 1) the coverage of items in the statements; and 2) the dynamic interaction between stock and flow concepts. With regard to coverage, we can further quantify two types of coverage: 1) the percentage of detailed line items estimated by the survey; and 2) the aggregate dollar values of the estimates. As an example of the first of these coverage measures, suppose that a balance-sheet concept had 10 detailed items and one survey estimated eight of them while another estimated only two of them. Then, the first survey has broader coverage (80 percent versus 20 percent). However, line-item coverage is not necessarily an accurate indicator of value coverage. If a survey had two estimates of the 10 balance-sheet items, and if each one were an estimate of the aggregate of five of the detailed items (for example, short-term assets and long-term assets), then the survey might produce a very high percentage of the total value of assets even though it didn’t include an estimate of each of the 10 items. Still, estimating the aggregate value of five items without estimating each individual item is prone to producing biased estimates due to the adverse effects of recall and reporting errors. The juxtaposed estimates reveal the extent to which this kind of aggregation effect appears in the survey estimates.

4.1. Balance Sheets and Income Statements

Balance sheets constructed from the U.S. surveys appear in Tables 2-a (assets) and 2-b (liabilities). The asset and liability estimates are reported as current market values to the best of our ability, although it is not always possible to be certain of the type of valuation reported by respondents. Assets are divided into financial and nonfinancial categories, with financial assets further divided into highly liquid current assets (short-term) and assets with other terms and liquidity (long-term). For financial assets, surveys usually obtain market values explicitly or by assumption; where they distinguish between face value and market value (for example, for a U.S. government saving bond) the latter is reported. For nonfinancial assets, the valuation issue is almost the same, except the potential distinction is between market value and book value.28 For housing assets, the surveys generally ask for the current (market) value of homes, but we cannot be sure they do not report the purchase price, which is a book value. For business assets, all surveys ask for a current (market) value, although the form of the question varies and may use analogous terms (for example, “sale price”). Liabilities are the current outstanding balances for debt, not the original loan amounts. Liabilities are divided into categories of revolving debt, characterized by an indefinite option to roll over the liability, and non-revolving debt. Because the maturity of debt is generally not known from the surveys and the term varies by debt contract within a category, the nonhousing debt categories are listed in rough order of liquidity from most to least liquid.

TABLE 2-a.

U.S. Surveys: Balance Sheets - Assets, various dates

| PSID | CES | SCF | HRS | SIPP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | 422,616 | 226,314 | 632,246 | 556,295 | 351,702 |

| Median | 151,000 | 170,600 | 240,000 | 67,113 | |

| Financial assets | 163,376 | 65,537 | 262,168 | 205,461 | 160,651 |

| (% of assets) | (39) | (29) | (41) | (37) | (46) |

| CURRENT ASSETS. | 95,883 | 65,115 | 140,176 | 125,898 | 102,642 |

| Cash | 29,850 | 30,849 | 30,354 | 34,733 | 12,434 |

| Currency | 12 | ||||

| Government-backed currency | 12 | ||||

| Private virtual currency | |||||

| Bank accounts | 29,850 | 30,849 | 30,342 | 34,733 | 536 |

| Checking accounts | 17,239 | 12,660 | 536 | ||

| Savings accounts | 13,610 | 17,682 | |||

| Other deposit accounts | 0 | 11,898 | |||

| Other current assets | 66,033 | 34,266 | 109,822 | 91,165 | 90,208 |

| Certificates of deposit | 4,994 | 9,354 | |||

| Bonds | 408 | 8,227 | 14,860 | 3,376 | |

| Mutual funds/hedge funds | 40,964 | 18,830 | |||

| Publicly traded equity | 56,335 | 33,858 | 48,874 | 66,951 | |

| Life insurance | 9,698 | 6,763 | 68,002 | ||

| LONG-TERM INVESTMENTS. | 67,493 | 422 | 121,992 | 79,563 | 58,009 |

| Retirement accounts | 67,493 | 97,007 | 79,563 | 54,759 | |

| Annuities | 5,490 | ||||

| Trusts/managed investment accounts | 13,773 | ||||

| Loans to people outside the HH | 422 | 5,722 | 361 | ||

| Other important assets | 2,889 | ||||

| Tangible (physical) assets | 259,240 | 160,777 | 362,445 | 336,951 | 191,051 |

| (% of assets) | (61) | (71) | (57) | (61) | (54) |

| Business | 51,404 | 108,760 | 55,006 | 25,921 | |

| Housing assets | 188,992 | 160,777 | 234,187 | 264,500 | 154,795 |

| Primary residence | 149,211 | 149,760 | 170,159 | 190,818 | 147,855 |

| Other real estate | 39,781 | 11,017 | 64,028 | 73,682 | 6,940 |

| Vehicles | 18,844 | 19,498 | 17,445 | 10,335 | |

| Unknown assets | 7,633 | 13,883 | |||

| (% of assets) | (1) | (2) |

SOURCES: Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) 2013, Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) 2012, Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) 2013, Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) 2012, and Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) 2011. See Section 2 for more details.

NOTES: Table entries are average dollar values for the survey’s unit of observation, approximately a household. Assets and liabilites are stocks dated as of the time of the survey, generally the end of the year. Sampling weights provided by each survey were used in calculating the average values in accordance with the survey’s data documentation. A more detailed data appendix and the Stata programs used to construct the tables are available at https://www.bostonfed.org/about-the-boston-fed/business-areas/consumer-payments-research-center.aspx.

TABLE 2-b.

U.S. Surveys: Balance Sheets - Liabilities, various dates

| PSID | CES | SCF | HRS | SIPP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liabilities | 82,288 | 73,668 | 112,306 | 64,614 | 61,979 |

| Median | 18,800 | 23,000 | 5,600 | 3,750 | |

| Revolving Debt | 2,671 | 4,512 | 2,185 | 2,661 | |

| (% of liabilities) | (3) | (6) | (2) | (4) | |

| Credit cards / charge cards | 2,671 | 4,447 | 2,096 | ||

| Revolving store accounts | 65 | 89 | |||

| Non-revolving Debt | 79,617 | 69,156 | 110,121 | 64,614 | 59,318 |

| (% of liabilities) | (97) | (94) | (98) | (100) | (96) |

| Housing | 67,506 | 58,143 | 87,223 | 58,584 | |

| Mortgages for primary residence | 54,856 | 52,559 | 63,889 | 48,984 | |

| Mortgages for investment real estate or second home | 12,650 | 3,086 | 19,598 | 4,440 | |

| HELOC/HEL | 2,498 | 3,556 | |||

| Loans for improvement | 180 | 5,160 | |||

| Loans on vehicles | 4,310 | 3,926 | 4,508 | 3,707 | |

| Education loans | 6,507 | 5,788 | |||

| Business loans | 10,317 | 5,338 | |||

| Investment loans (e.g., margin loans) | 289 | 102 | |||

| Unsecured personal loans | |||||

| Loans against pension plan | 288 | ||||

| Payday loans / pawn shops | |||||

| Other loans | 1,294 | 7,087 | 1,708 | 6,030 | 50,171 |

| Net worth (equity) | 340,328 | 152,646 | 519,940 | 491,681 | 289,723 |

| Cumulative net gifts received | |||||

| Cumulative savings |

SOURCES: Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) 2013, Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) 2012, Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) 2013, Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) 2012, and Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) 2011. See Section 2 for more details.

NOTES: Table entries are average dollar values for the survey’s unit of observation, approximately a household. Assets and liabilites are stocks dated as of the time of the survey, generally the end of the year. Sampling weights provided by each survey were used in calculating the average values in accordance with the survey’s data documentation. A more detailed data appendix and the Stata programs used to construct the tables are available at https://www.bostonfed.org/about-the-boston-fed/business-areas/consumer-payments-research-center.aspx.

All the surveys report an estimate of total assets in Table 2-a. U.S. households own average assets worth as much as $632,246, according to the SCF, less half that amount, $226,314, in the CE survey. The HRS estimate of $556,295 is close to the SCF estimate, despite being limited to older consumers. The breakdown of asset types is similar for all the surveys. Financial assets generally account for less than half of asset values, 29 to 41 percent, despite variation in the number and type of detailed asset categories. Tangible (physical) assets represent the majority of asset values. Within financial assets, cash accounts for roughly $30,000 for all but the SIPP, where it accounts for roughly $12,000, and most is held in bank accounts. Only the SCF contains an estimate of currency, but even that is not a direct estimate of actual currency holdings of the household.29 Overall, estimates of balance-sheet assets are relatively comprehensive for all surveys, as shown by their similar aggregate values and by the breadth of coverage across detailed asset categories. The SCF is the most comprehensive, with asset estimates in every category except short-term assets other than bank accounts (checking and saving); the PSID, HRS, and SIPP are almost as comprehensive as the SCF. The CE is much less comprehensive and has considerably lower asset values.

All the surveys also report an estimate of total liabilities. U.S. households have average liabilities ranging across the surveys between $61,979 and $112,306, much lower than the value of total assets and exhibiting less variation than across surveys. Housing debt is by far the largest portion of liabilities, ranging from $58,143 to $87,228 in all surveys where it is reported. The HRS asks specifically only about housing-related debt, with a catch-all question for other loans. The SIPP does not permit an exact estimate for housing-related debt, but the “other loans” category most likely includes some housing-related debt. While estimates of balance-sheet liabilities are somewhat comprehensive for most surveys, they are not as comprehensive as the estimates of assets. The aggregate values vary less and there is less line-item coverage across detailed categories of liabilities. Once again, the SCF is the most comprehensive, with liability estimates in nearly every category. The PSID is almost as comprehensive as the SCF. The other surveys are less comprehensive, although in different ways. Given the estimates of total assets and total liabilities, household net worth ranges from $152,646 in the CE to $519,940 in the SCF.

Income statements constructed from the U.S. surveys appear in Table 3. Income is divided into two main categories: compensation of employees (the most common source of U.S. household income) and other income. The latter includes income from all types of businesses owned and operated by households. Expenditures also are divided into two main categories: production costs and taxes. As explained above, the production costs of households are expenditures associated with businesses operated directly by a U.S. household; these businesses include sole proprietorships, partnerships, and certain Limited Liability Corporations (LLC).30 Unlike in Thailand, where most households operate a business (typically agricultural), only a minority of U.S. households have a business.31 For the minority of U.S. households with a business, it would be natural to apply corporate financial accounting to income (revenues) and expenses, as in ST. However, none of the surveys provides sufficient information about household business activity, so we use the simpler approximation of revenues as “income” to accommodate the majority of U.S. households without a business. Furthermore, all income-statement estimates are reported on a cash basis of accounting, so revenues and expenses are reported for the period when the cash is received (income) or paid out (expenditures), because this method is the primary way data are collected in the U.S. surveys.

TABLE 3.

U.S. Surveys: Income Statements, various dates

| PSID | CES | SCF | HRS | SIPP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 67,187 | 65,316 | 83,863 | 79,779 | 61,431 |

| Median | 44,500 | 46,774 | 45,000 | 46,300 | 45,396 |

| Labor Income | 53,623 | 51,543 | 53,192 | 42,377 | 48,767 |

| (% of total income) | (80) | (79) | (63) | (53) | (79) |

| Wages and salaries | 53,473 | 51,543 | 53,192 | ||

| Professional practice or trade | 113 | ||||

| Other Labor Earnings | 37 | ||||

| Production Income | 3,748 | 3,075 | 11,347 | 1,144 | |

| (% of total income) | (6) | (5) | (14) | (2) | |

| Business income (self-employment) | 2,472 | 2,926 | 11,347 | ||

| Rent | 1,276 | 149 | 1,144 | ||

| Other income | 9,816 | 10,698 | 19,324 | 37,402 | 18,176 |

| (% of total income) | (15) | (16) | (23) | (47) | (30) |

| Interest, dividends, etc | 2,206 | 1,204 | 6,682 | 18,093 | |

| Government transfer receipts | 1,302 | 5,812 | 10,670 | 12,415 | 7,294 |

| Other transfer receipts, from business | 131 | 423 | |||

| Other transfer receipts, from persons | 380 | 372 | |||

| All other income | 6,177 | 3,302 | 1,600 | 6,471 | 10,882 |

| Expenditures | 1,837 | 4,345 | 2,007 | 0 | 22,487 |

| Production Costs | |||||

| (% of total expenditures) | |||||

| Depreciation | |||||

| Capital losses | |||||

| Business Expenses | |||||

| Cost of Labor Provision | |||||

| Cost of Other Production Activities | |||||

| Taxes | 1,837 | 4,345 | 2,007 | 2,798 | |

| (% of total expenditures) | (100) | (100) | (100) | ||

| Employment taxes | 2,508 | 585 | |||

| Other taxes | 1,837 | 1,837 | 2,007 | 2,213 | |

| Net income | 65,350 | 60,971 | 81,856 | 79,779 | 38,944 |

SOURCES: Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) 2013, Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) 2012, Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) 2013, Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) 2012, and Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) 2011. See Section 2 for more details.

NOTES: Table entries are average dollar values for the survey’s unit of observation, approximately a household. Income and expenses are reported for the prior 12 months, or annualized where necessary. Sampling weights provided by each survey were used in calculating the average values in accordance with the survey’s data documentation. A more detailed data appendix and the Stata programs used to construct the tables are available at https://www.bostonfed.org/about-the-boston-fed/business-areas/consumer-payments-research-center.aspx.

All of the surveys report an estimate of total income (revenues). U.S. households received average total income of $61,431 to $83,863 per year. Estimates of labor income are even more similar across surveys, ranging only between $42,377 and $53,623, essentially all of which is wages and salaries. Estimates of other income types vary more, ranging between $9,816 and $37,402, but account for less than one-quarter of total income, except for the HRS estimates, which represent 45 percent of total income. Overall, income estimates are the most comprehensive and consistent portion of the household financial statements across surveys, most likely because employment compensation is widespread among U.S. households and the data are relatively easy to collect. Estimates of income other than employment compensation are less uniform across the surveys due to the unavailability of some detailed line-item categories.

Although three surveys (the PSID, CES, and SCF) have estimates of business income, none of them provides much information about household business expenditures. They ask few, if any, questions about household business activity (aside from the mere existence of a home business). No survey has an estimate of production costs for household businesses. Only three surveys with business income have estimates of taxes (these estimates average less than $5,000 per household), and only the CE reports employment taxes. Tax expenditures are those paid directly by households and do not include taxes deducted by employers or paid by third parties on behalf of households.

Given their estimates of total income and total expenditures, all of the surveys provide estimates of net income (income less expenditures), which range from $60,971 (CE) to $81,856 (SCF), as shown at the bottom of in Table 3. The HRS does not collect expenses, so its net income equals total income. Net income is similar to income in the other surveys because expenditures are relatively small (taxes only). Household net income is treated as retained earnings that are distributed to household members for consumption and investment expenditures, which are recorded in the statement of cash flows (described below).

4.2. Quantifying Integration by Coverage

We wish to characterize the degree to which surveys are integrated with household financial statements in terms of coverage. We propose to develop the criteria for measuring this kind of integration by quantifying the extent to which a particular household financial survey covers (includes) the breadth of the line items in standard balance sheets and income statements. There are at least two dimensions along which integration by item coverage could be measured using the estimates from the preceding subsection. One is the fraction of detailed line items for which a survey provides estimates (“line-item coverage”). Another is the fraction of the total dollar value of all line items estimated by a survey (“value coverage”). The two measures are independent and not necessarily highly correlated. A survey could cover most items in the financial statements but underestimate them significantly; likewise, a survey might cover only a small number of items but obtain very high-value estimates if the items covered include mainly the highest-valued items. The latter situation may occur when a survey only collects data on two aggregate subcategories (such as short-term and long-term assets) but collects none on the detailed line items within each subcategory.

We construct the measure of line-item coverage as follows. We define the range of each financial statement as the number of the most detailed line items (rows) from the tables earlier in this section. Then, we count the number of line items (rows) for which each survey provides a dollar-value estimate. The coverage estimate of integration is the proportion of line items estimated relative to the total number of line items. We call this the “item-coverage ratio,” and we construct two separate ratios, one for the balance sheet and one for the income statement. This measure reflects only the extensive margin of coverage because it does not account for the magnitude of the dollar values in each line item; thus, it may not give a complete reflection of coverage for total assets, liabilities, income, or expenditures.

We construct the measure of value coverage analogously, as follows. We use the nominal dollar values for each individual line item in the statements to construct the aggregate total values (sum of all individual items) for each statement and divide the aggregate value by the best available per-household estimate of the relevant metric for the U.S. population. For the balance sheet, we use total assets and total liabilities from the Flow of Funds accounts as the denominator. For the income statement, we use personal income from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA). The “value-coverage ratio” represents survey coverage of the intensive margin of coverage. The difference between the two types of ratios reflects the extent to which a survey’s coverage of financial statements is more integrated in its intensive or extensive coverage of financial statements. To the extent that one wishes to construct accurate estimates of aggregate U.S. household financial conditions, the dollar-value ratio may be more important.

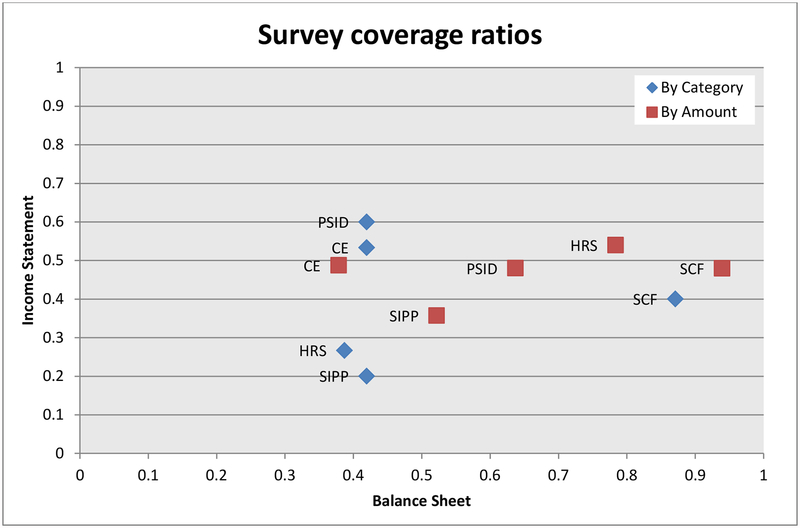

Figure 3 provides scatter plots of the item-coverage ratio (blue diamonds) and value-coverage ratio (red squares) for the balance sheet and income statement. The feasible range of both ratios is [0, 1], with the upper end indicating that a survey has estimates of every single item in the corresponding financial statement. Recall that the ratios are independent and may not be highly correlated. Thus, the item-coverage ratio does not necessarily reflect how well a survey produces aggregate estimates of the data, and the value-coverage ratio does not necessarily reflect how well a survey covers the number of line items in the financial statements. Also, we make one important adjustment to the income statement ratios to adjust for the application to households. As shown in the next subsection, household consumption and durable goods investment are listed in the statement of cash flows rather than the income statement. However, for the purpose of quantifying the overall coverage of household income and total household expenditures, both business-related expenditures and household consumption or investment expenditures, we include all types of expenditures in constructing the coverage ratios for the income statements.

FIGURE 3.

Financial Statement Line-Item Coverage Ratios for U.S. Surveys

None of the U.S. surveys is completely integrated (ratio of 1.0) with aggregate financial conditions for either statement, as can be seen from Figure 3. In fact, no survey has either type of coverage ratio that is greater than 0.6 for both financial statements. However, four of the five balance-sheet ratios are greater than 0.5 (except CE) and four of the five income-statement ratios are about 0.5 (except SIPP). The key differences across surveys occur in both types of coverage ratios for the balance sheets. The SCF has nearly complete value coverage of the balance sheet (above 0.9 by value) and the HRS has a value ratio about 0.8 (by value). Most surveys have item-coverage ratios of about half of the balance-sheet line items except the SCF, which covers the vast majority of line items. Variation across surveys is less in the item-coverage ratios for income statements.

4.3. Quantifying Integration by Dynamics

We also wish to characterize the degree to which surveys are integrated with household financial statements in terms of dynamics. Our proposed criterion for measuring this kind of integration is a quantification of the extent to which the estimated stock-flow identity holds in the survey estimates of household financial statements. The statement of cash flows is well suited to quantifying this measure of integration because it provides the linkage between the income statement (flows of income and expenditures) and changes in the balance sheet (stocks of assets and liabilities), assuming all stocks and flows are measured exactly and comprehensively. As explained in Section 3, however, the cash-flows error that arises in practice quantifies how well the balance sheet and income statement are integrated over time. Cash-flows errors represent consequences of incomplete item coverage of financial statements, as well as various forms of mismeasurement of the items in the financial statements.

Table 4 reports estimates of the statements of cash flows for each survey. Starting with net income (from the income statement), the estimated change in cash flows is the sum of three types of cash flows: from production, from consumption and investment, and from financing. To construct these statements, we have to estimate the elements of the cash flows from financing using estimated changes in the relevant assets and liabilities from the prior-period balance sheet. This methodology produces a cash-flows estimate that is a residual difference between net income and net cash flows, rather than a direct measure of the gross cash flows in and out of the balance sheet, because the latter are not available from the U.S. surveys. For comparison, we estimate the change in cash holdings directly from the current and prior-period balance sheets.32

TABLE 4.

U.S. Surveys: Statements of Cash Flows

| (Cash defined as Current Assets) | PSID 2010–2012 |

CES 2011–2012 |

SCF 2010–2013 |

HRS 2010–2012 |

SIPP 2010–2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net income (+) | 65,350 | 60,971 | 81,856 | 79,779 | 38,944 |

| Adjustments: | |||||

| Depreciation (+) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Change in Account Receivables (−) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Change in Account Payables (+) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Change in Inventory (−) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Change in Other (not Cash) Current Assets (−) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Consumption of Household Produced Outputs (−) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cash flows from Production | 65,350 | 60,971 | 81,856 | 79,779 | 38,944 |

| Consumption expenditure (−) | −43,766 | −44,849 | −28,850 | −45,073 | −22,487 |

| Capital (durable goods) expenditure (−) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cash flows from Consumption and Investment | −43,766 | −44,849 | −28,850 | −45,073 | −22,487 |

| Transfers to/from Long-Term Investments | −362 | 0 | 1,231 | 0 | 0 |

| Lending (−) | 0 | −151 | 1,359 | 50 | 4,452 |

| Borrowing (+) | 4,230 | 8,089 | −4,349 | −3,757 | −8,988 |

| Net Gifts Received (+) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cash flows from Financing | 3,868 | 7,938 | −1,759 | −3,707 | −4,536 |

| Change in Cash Holding (from Statement of Cash Flows) | 25,452 | 24,060 | 51,247 | 31,000 | 11,921 |

| Change in Cash Holding (from Statement of Balance Sheet) | 3,091 | 17,770 | 3,843 | 1,678 | −18,622 |

| Cash flows error | 22,362 | 6,290 | 47,404 | 29,322 | 30,543 |

| Internal Error | 25% | 13% | 37% | 24% | 25% |

| External Error | 30% | 8% | 61% | 39% | 42% |

SOURCES: Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) 2010–2013, Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE) 2011–2012, Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) 2010–2013, Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) 2010–2012, and Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) 2010–2011. See Section 2 for more details.

NOTES: Table entries are average dollar values for the survey’s unit of observation, approximately a household. Cash flows are at a yearly rate and are constructed with the most recent prior data available. Sampling weights provided by each survey were used in calculating the average values. A more detailed data appendix and the Stata programs used to construct the tables are available at https://www.bostonfed.org/about-the-boston-fed/business-areas/consumer-payments-research-center.aspx.

The degree of dynamic integration is defined as the difference (error) between the estimated cash flows variables and the change in cash holdings estimated from the current and prior period balance sheets, expressed in dollar terms and as a percentage of the lagged stock of cash. We call this the “internal” cash-flows error because it is calculated using only the survey’s estimates of stocks and flows. However, cash holdings from any particular survey may differ from the actual aggregate U.S. estimate of cash holdings (from the Flow of Funds), so these errors may not accurately represent the true degree of integration. Therefore, we also include the change in household cash holdings from the Flow of Funds (same for each survey) and construct errors in the survey cash-flows estimates relative to the actual Flow of Funds cash to give a better measure of dynamic integration. We call this the “external” cash-flows error.

As measured by their ability to track stock-flow identities in the statements of cash flows, the U.S. surveys exhibit relatively weak dynamic integration, and the degree of integration varies widely across surveys. The absolute value of the internal cash-flows error ranges from $6,290 (CE) to $47,404 (SCF). Note that these errors are just one estimate in a time-series of errors that could be estimated, and other errors might be smaller in absolute value during other periods. However, the sheer magnitude of these internal errors suggests significant gaps in tracking household financial conditions over time, even within the self-contained estimates of a particular survey.33 The cash-flows errors are reported in percentage terms relative to the two benchmarks: 1) the lagged cash stock from the survey’s balance sheet (internal error); and 2) the lagged cash stock from the Flow of Funds aggregate benchmark data (external error). The internal errors are relatively large, ranging from about 13 percent to 37 percent of lagged cash (CE and SCF, respectively). The survey estimates of cash flows are generally less than the external benchmark: all but one of the external cash-flows errors are even larger in absolute value, ranging from about 11 percent to 61 percent of lagged cash.

5. The TTMS and DCPC

Moving beyond the U.S. household surveys, we now focus on two other surveys that offer improved integration with financial statements and reflect better measurement of certain aspects of household economic conditions. The TTMS and DCPC are quite different in most regards. The TTMS is a comprehensive survey of household economic conditions, including home businesses; it is administered to Thai households, which are relatively low-income, less-developed, and located in rural geographic regions. In contrast, the DCPC is a relatively narrow consumer survey that is administered to U.S. consumers and is focused on payment choices. Nevertheless, the TTMS and DCPC both embody certain elements of improved integration with financial statements. The TTMS is heavily focused on the most basic and liquid M1 portions of “cash” (or current assets). The DCPC includes currency and is unique in this respect among the U.S. surveys that we analyze here. The DCPC also features other means of payment, for example, payments that use deposit accounts, although it does not track the level of these deposits.

This section compares and contrasts the TTMS and DCPC surveys. First, we present estimated balance sheets and income statements for each survey and discuss their degrees of integration by item coverage. Next, for each survey, we describe the methodology for measuring cash flows. Finally, we assess its degree of integration by dynamics, emphasizing its relatively high integration compared with the U.S. surveys. For this section, we combine survey responses from the DCPC with responses from the SCPC because both surveys are needed to estimate the financial statements as thoroughly as possible. For simplicity, we refer to the combined DCPC and SCPC estimates “CPC.”

5.1. Balance Sheets and Income Statements

Balance sheets and income statements constructed from the TTMS and CPC surveys appear in Table 5 and Table 6, respectively. These statements are designed and organized similarly to the analogous statements from the U.S. surveys, with a few exceptions. In these tables, the TTMS and CPC data represent exactly the same time period (October 2012), and the TTMS estimates have been converted to U.S. dollars using the Thai baht exchange rate for October 2012. Unlike the U.S. survey entries, the entries are not annualized because both the TTMS and the DCPC are designed to be monthly surveys.

TABLE 5.

TTMS and SCPC/DCPC: Balance Sheets, October 2012

| TTMS | DCPC/SCPC | |

|---|---|---|

| Assets | 89,082 | 301,425 |

| Median | 146,053 | |

| Financial assets | 35,553 | 836 |

| (% of assets) | (40) | (0) |

| CURRENT ASSETS. | 35,321 | 836 |

| Cash | 35,332 | 836 |

| Currency | 30,874 | 836 |

| Government-backed currency | 30,874 | 836 |

| Bank accounts | 4,458 | |

| Other current assets | −11 | |

| Certificates of deposit | ||

| Net ROSCA position | −11 | |

| Accounts receivable | 0 | |

| Bonds | ||

| Mutual funds/hedge funds | ||

| Publicly traded equity | ||

| Life insurance | ||

| LONG-TERM INVESTMENTS. | 232 | |

| Retirement accounts | ||

| Annuities | ||

| Trusts/managed investment accounts | ||

| Other lending | 232 | |

| Tangible (physical) assets | 53,529 | 148,421 |

| (% of assets) | (60) | (49) |

| Business assets | 334 | |

| Agricultural assets | 1,243 | |

| Housing/household assets | 4,582 | 148,421 |

| Primary residence | 148,421 | |

| Inventories | 8,394 | |

| Livestock | 290 | |

| Other nonfinancial assets | 38,687 | |

| Unknown assets | 152,168 | |

| (% of assets) | (50) | |

| Liabilities | 5,317 | 120,689 |

| Median | 42,935 | |

| Revolving Debt | 5,306 | |

| (% of liabilities) | (4) | |

| Credit cards / charge cards | 5,306 | |

| Revolving store accounts | ||

| Non-revolving Debt | 5,317 | 115,383 |

| (% of liabilities) | (96) | |

| Housing | 67,278 | |

| Mortgages for primary residence | 67,278 | |

| Mortgages for investment real estate | ||

| HELOC/HEL | ||

| Loans for improvement | ||

| Accounts payable | 1,480 | |

| Loans on vehicles | ||

| Education loans | ||

| Business loans | ||

| Investment loans (e.g., margin loans) | ||

| Unsecured personal loans | ||

| Loans against pension plan | ||

| Payday loans / pawn shops | ||

| Other loans | 3,837 | 48,105 |

| Net worth (equity) | 83,765 | 180,736 |

| Cumulative net gifts received | ||

| Cumulative savings | 56,779 |

NOTES: Thai Baht converted to U.S. Dollars at a rate of 30.68 Baht per Dollar. Values are stocks as of the time of the survey, which for the CPC is between the beginning of September and the end of October. TTMS entries are at the household level. CPC entries are either at the household level or converted to a household level by multiplying consumer values by 2.045. A more detailed appendix and the Stata programs used to construct the tables are available at https://www.bostonfed.org/about-the-boston-fed/business-areas/consumer-payments-research-center.aspx.

SOURCES: Townsend Thai Monthly Survey (TTMS), Survey of Consumer Payment Choice (SCPC).

Table 6.

TTMS and SCPC/DCPC: Income Statements, October 2012

| TTMS | SCPC/DCPC | |

|---|---|---|

| Income | 1,643 | 5,921 |

| Median | 4,413 | |

| Censored income | 4,789 | |

| Labor Income | 252 | |

| (% of total income) | (15) | |

| Production Income | 1,368 | |

| (% of total income) | (83) | |

| Business | 326 | |

| Agricultural activities | 1,042 | |

| Cultivation | 536 | |

| Livestock | 392 | |

| Produce | 390 | |

| Capital gains | 2 | |

| Fish and shrimp | 114 | |

| Other income | 23 | |

| (% of total income) | (1) | |

| Expenditures | 813 | 1,840 |

| Production Costs | 813 | |

| (% of total expenditures) | (100) | |

| Business | 251 | |

| Agricultural activities | 529 | |

| Cultivation | 133 | |

| Livestock | 292 | |

| Capital losses | 1 | |

| Depreciation | 12 | |

| Other expenses | 280 | |

| Fish and shrimp | 104 | |

| Labor provision | 32 | |

| Other production activities | 1 | |

| Taxes | 1,840 | |

| (% of total expenditures) | (100) | |

| Net income | 830 | 4,081 |

NOTES: Thai Baht converted to U.S. Dollars at a rate of 30.68 Baht per Dollar. Values are stocks as of the time of the survey, which for the CPC is between the beginning of September and the end of October. TTMS entries are at the household level. CPC entries are either at the household level or converted to a household level by multiplying consumer values by 2.045. CPC household income is originally reported in buckets; precise estimates are imputed with the help of SCF data. A more detailed appendix and the Stata programs used to construct the tables are available at https://www.bostonfed.org/about-the-boston-fed/business-areas/consumer-payments-research-center.aspx.

SOURCES: Townsend Thai Monthly Survey (TTMS), Diary of Consumer Payment Choice (DCPC), Survey of Consumer Payment Choice (SCPC)