Sponges represent ecologically important models to understand the evolution of symbiotic interactions of metazoans with microbial symbionts. Thaumarchaeota are commonly found in sponges, but their potential adaptations to a host-associated lifestyle are largely unknown. Here, we present three novel sponge-associated thaumarchaeal species and compare their genomic and predicted functional features with those of closely related free-living counterparts. We found different degrees of specialization of these thaumarchaeal species to the sponge environment that is reflected in their host distribution and their predicted molecular and metabolic properties. Our results indicate that Thaumarchaeota may have reached different stages of evolutionary adaptation in their symbiosis with sponges.

KEYWORDS: evolution, genetic features, host associated, sponge microbiome, symbionts

ABSTRACT

Thaumarchaeota are frequently reported to associate with marine sponges (phylum Porifera); however, little is known about the features that distinguish them from their free-living thaumarchaeal counterparts. In this study, thaumarchaeal metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) were reconstructed from metagenomic data sets derived from the marine sponges Hexadella detritifera, Hexadella cf. detritifera, and Stylissa flabelliformis. Phylogenetic and taxonomic analyses revealed that the three thaumarchaeal MAGs represent two new species within the genus Nitrosopumilus and one novel genus, for which we propose the names “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus detritiferus,” and “Candidatus UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” (the U superscript indicates that the taxon is uncultured). Comparison of these genomes to data from the Sponge Earth Microbiome Project revealed that “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” has been exclusively detected in sponges and can hence be classified as a specialist, while “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” are also detected outside the sponge holobiont and likely lead a generalist lifestyle. Comparison of the sponge-associated MAGs to genomes of free-living Thaumarchaeota revealed signatures that indicate functional features of a sponge-associated lifestyle, and these features were related to nutrient transport and metabolism, restriction-modification, defense mechanisms, and host interactions. Each species exhibited distinct functional traits, suggesting that they have reached different stages of evolutionary adaptation and/or occupy distinct ecological niches within their sponge hosts. Our study therefore offers new evolutionary and ecological insights into the symbiosis between sponges and their thaumarchaeal symbionts.

IMPORTANCE Sponges represent ecologically important models to understand the evolution of symbiotic interactions of metazoans with microbial symbionts. Thaumarchaeota are commonly found in sponges, but their potential adaptations to a host-associated lifestyle are largely unknown. Here, we present three novel sponge-associated thaumarchaeal species and compare their genomic and predicted functional features with those of closely related free-living counterparts. We found different degrees of specialization of these thaumarchaeal species to the sponge environment that is reflected in their host distribution and their predicted molecular and metabolic properties. Our results indicate that Thaumarchaeota may have reached different stages of evolutionary adaptation in their symbiosis with sponges.

INTRODUCTION

Marine sponges are a group of sessile animals, which harbor diverse microorganisms that often form stable and specific associations with their host (1–3). Phylogenetic analyses have shown that sponge microbiota often contain members of the phyla Proteobacteria (mainly Gamma- and Alphaproteobacteria), Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Chloroflexi, Nitrospirae, Cyanobacteria, “Candidatus Poribacteria,” and Thaumarchaeota (4–6). Studies analyzing isolate genomes or metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from a few of these bacterial phyla have postulated several adaptive features of sponge-associated symbionts compared to their free-living relatives, including an enrichment of unique eukaryotic-like proteins (ELPs) and methyltransferases in the cyanobacterial “Candidatus Synechococcus spongiarum” (7–9), an abundance of diverse phyH domain proteins in Poribacteria (10), an enrichment of CRISPR-Cas systems, ABC transporters, and restriction-modification systems in the alphaproteobacterial Rhodospirillaceae (11), and functions related to carbohydrate uptake, phage defense, and protein secretion in sulfur-oxidizing Gammaproteobacteria (12, 13). In contrast, other Proteobacteria such as the genera Aquimarina and Pseudovibrio have few or no obvious features that distinguish them from their free-living counterparts (9).

Thaumarchaeota occur in diverse habitats, including seawater (14–17), hot springs (18), freshwater (19), industrial wastewater (20, 21), terrestrial soil (22–25), marine sediments (26, 27), and marine sponges (28–33). Previous work has shown that some Thaumarchaeota form so-called “sponge-specific” or “sponge-enriched” clades, which are defined by monophyletic 16S rRNA sequence clusters found either exclusively or highly enriched in sponges compared to other environments (1, 5, 34, 35). This indicates that some Thaumarchaeota clades might have diverged from their free-living counterparts because of adaptation to a sponge-associated lifestyle. Thaumarchaeota are known to be ecologically important autotrophic, aerobic ammonia oxidizers, which use urea and probably creatinine as indirect sources of ammonia (23, 36) and produce NO (37), N2O (38), and ether-lipid components (39). A possible uptake of urea and amino acids and the expression of a CO2 fixation pathway have also been recently reported for a sponge-associated Thaumarchaeota (33), but no other genomic features indicative of adaptation to the sponge environment have been reported.

This study aimed to generate hypotheses on the potential functional adaptations based on the comparative genomic analyses of novel thaumarchaeal symbionts of sponges. For this purpose, we reconstructed MAGs from metagenomic data derived from the sponges Stylissa flabelliformis, Hexadella detritifera, and Hexadella cf. detritifera and compared them to genomes from closely related free-living Thaumarchaeota.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

MAG reconstruction and phylogenetic analyses define novel thaumarchaeal taxa.

The seven sponge specimens investigated in this study (Table 1) each contained a single 16S rRNA gene sequence belonging to the phylum Thaumarchaeota as reconstructed using the Mapping-Assisted Targeted Assembly for Metagenomics (MATAM) algorithm (40). Similarly, only one thaumarchaeal MAG was recovered for each sample, to which the 16S rRNA gene sequence could be aligned with high similarity (99.95% ± 0.08%). MAGs had average sizes of 1.18 ± 0.08 Mb, no heterogeneity, contamination levels of 0.57% ± 0.51% and completeness of 84.36% ± 10.91% as assessed by CheckM (41).

TABLE 1.

Statistics of sponge-associated thaumarchaeal MAGs

| Sample | MAG | Proposed taxona | Host species | MAG

size (Mbp) |

Completeness

(%) |

Estimated

genome size (Mbp) |

Contamination | Avg coverage of MAG |

16S rRNA

gene length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B06 | HdNhB06 | “Ca. UN. hexadellus” | Hexadella dedritifera | 1.25 | 91.83 | 1.36 | 0.96 | 28× | 1,365 |

| D6 | HdNhD6 | “Ca. UN. hexadellus” | Hexadella dedritifera | 1.12 | 92.31 | 1.21 | 0 | 89× | 1,041 |

| H08 | HdNdH8 | “Ca. UN. detritiferus” | Hexadella cf. dedritifera | 1.13 | 89.26 | 1.27 | 0 | 11× | 1,448 |

| H13 | HdNdH13 | “Ca. UN. detritiferus” | Hexadella cf. dedritifera | 1.12 | 89.9 | 1.25 | 0.07 | 106× | 1,600 |

| S13 | SfCsS13 | “Ca. UC. stylissum” | Stylissa flabelliformis | 1.31 | 85.58 | 1.53 | 0.96 | 9× | 1,432 |

| S14 | SfCsS14 | “Ca. UC. stylissum” | Stylissa flabelliformis | 1.13 | 80.13 | 1.41 | 1.04 | 6× | 1,430 |

| S15 | SfCsS15 | “Ca. UC. stylissum” | Stylissa flabelliformis | 1.17 | 61.54 | 1.90 | 0.96 | 5× | 1,431 |

The three proposed taxa are “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus detritiferus,” and “Candidatus UCenporiarchaeum stylissum.”

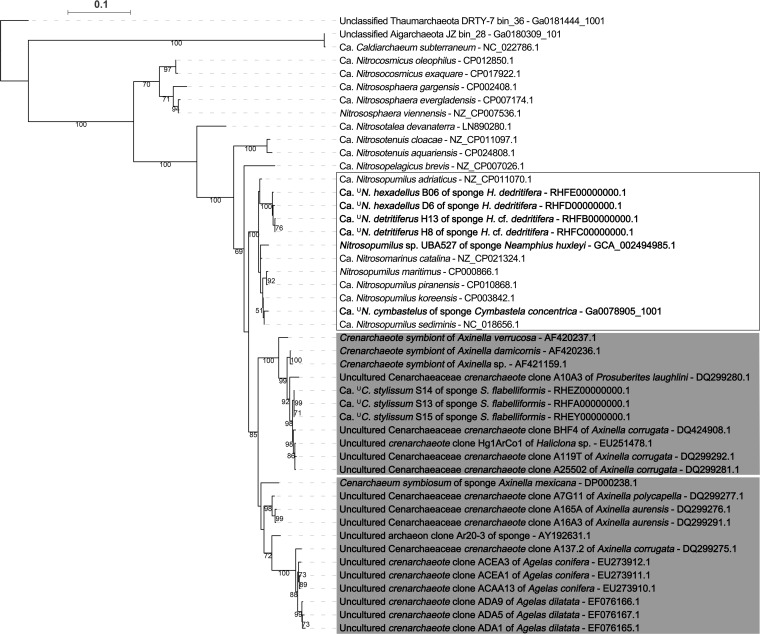

Maximum-likelihood trees were constructed for the 16S rRNA genes or single-copy genes (SCG) from the MAGs and genomes of their close relatives in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant nucleotide (NT) database (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). These two trees showed very similar patterns, with the sponge-derived Thaumarchaeota falling into two distinct clades (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). One clade was comprised of the three MAGs from Stylissa flabelliformis, which were 99.91% ± 0.04% similar to each other at the 16S rRNA gene level and formed an apparent sister clade (98.81% ± 0.11% similar) to “Candidatus Cenarchaeum symbiosum” (GenBank accession number DP000238.1), which was previously reported from the marine sponge genus Axinella (30). The other clade was composed of four genomes from the Hexadella samples, which were related to the free-living Nitrosopumilus maritimus (GenBank accession number CP000866.1) from seawater. The reconstructed 16S rRNA gene sequences of this clade were 98.65% ± 0.31% similar to other sequences from the genus Nitrosopumilus and had 99.58% ± 0.20% similarity to each other. Our analysis also included two MAGs (GCA_002494985.1 and GCA_002506665.1) from the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB), one of which (GCA_002494985.1) also contained a partial 16S rRNA gene. These MAGs were derived from a sample of the deep-sea sponge Neamphius huxleyi. However, in the phylogenetic trees, these organisms clustered separately from each other as well as from the MAGs analyzed here and were more closely related to free-living Thaumarchaeota. They were therefore not further analyzed.

FIG 1.

Maximum-likelihood tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences (≥1,000 bp) for sponge-associated and free-living Thaumarchaeota. Results ≥50% are shown for 1,000 bootstraps. The tree is rooted with two Aigarchaeota (“Candidatus Caldiarchaeum subterraneum” and an unclassified Aigarchaeota) and one unclassified Thaumarchaeota, and sponge-derived sequences are displayed in boldface type. Gray shaded boxes represent sponge-specific monophyletic clusters, and white boxes represent monophyletic clusters containing both sponge-derived sequences and free-living sequences. Bars indicate 10% sequence divergence.

Maximum-likelihood trees of 16S rRNA gene sequences (A) and SCG (B) for sponge-derived Thaumarchaeota and free-living relatives. Results of ≥50% are shown for 1,000 bootstraps. The trees are rooted with two Aigarchaeota (“Candidatus Caldiarchaeum subterraneum” and an unclassified Aigarchaeota) and one unclassified Thaumarchaeota, and sponge-derived sequences are displayed in boldface type. Shaded boxes represent sponge-specific monophyletic clusters, and open boxes represent monophyletic clusters containing both sponge-derived sequences and free-living sequences. Bars indicate 10% sequence divergence. Download FIG S1, TIF file, 2.0 MB (2MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2019 Zhang et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Details of completed thaumarchaeal reference genomes. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (16.4KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Zhang et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

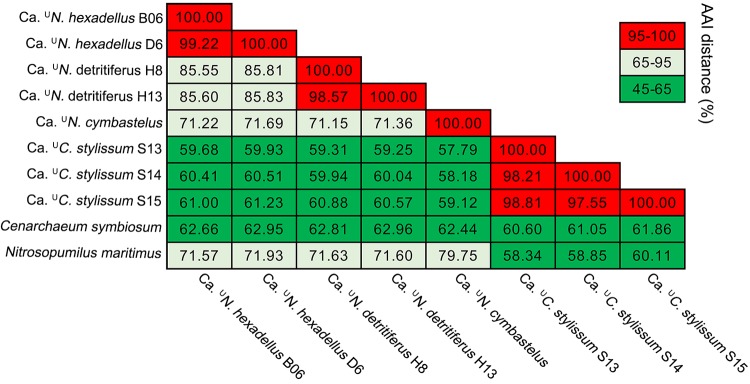

The thaumarchaeal MAGs from Stylissa flabelliformis had pairwise amino acid identities (AAI) of 57.30% ± 7.30% with “Ca. Cenarchaeum symbiosum” (Fig. 2), suggesting that they represent a different genus within the same family (45 to 65%) based on the criteria proposed by Konstantinidis et al. (42). Pairwise AAI distance between MAGs from S. flabelliformis were 98.19% ± 0.63%. We therefore propose the novel genus “Candidatus Cenporiarchaeum” with the species “Candidatus UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” (the U superscript indicates that the taxon is uncultured) represented by the MAGs found in S. flabelliformis.

FIG 2.

Pairwise average amino acid identity (AAI) distances among the genomes of sponge-derived Thaumarchaeota and their closest relatives. The color bar indicates the range of AAI distances that represents different taxonomical levels: the level of species (95 to 100%), genus (65 to 95%), and family (45 to 65%).

MAGs from the Hexadella samples had AAI distances of 70.95% ± 14.12% with Nitrosopumilus sp. (GCA_000328925.1), indicating that they belong to the same genus (65 to 95%) but are distinct species (42). Pairwise AAI distances between the MAGs from the Hexadella dedritifera and Hexadella cf. dedritifera were 99.22% and 98.57%, respectively. AAI distances between genomes from the two sponge taxa were 85.70% ± 0.14%, indicating two distinct species. We therefore propose the names “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” for the species found in H. dedritifera, and “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” for the species found in H. cf. dedritifera.

Another thaumarchaeal genome (Ga0078905) from the sponge Cymbastela concentrica from a previous study (33) had AAI values of 71.36% ± 0.24% with “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” indicating a different species within the same genus, and we propose here the name “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus cymbastelus.”

Size and GC content of sponge-associated thaumarchaeal genomes.

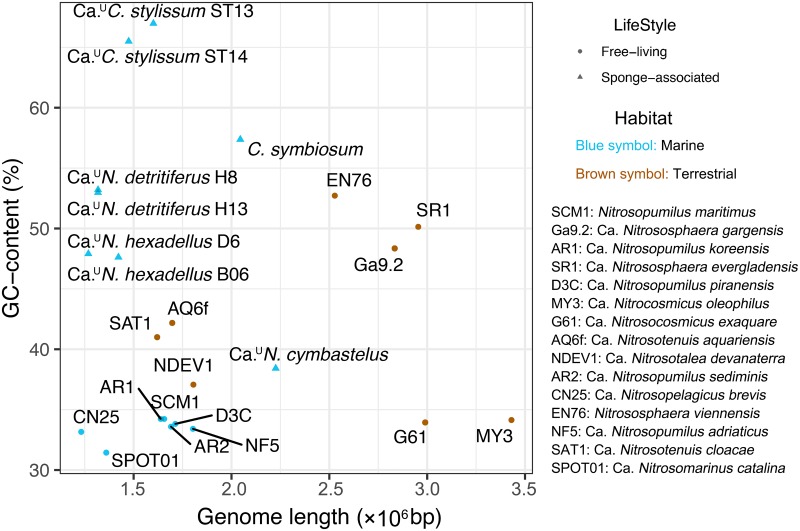

Genome reduction is often considered a signature of microbial symbiosis, as genes no longer required for a host-associated lifestyle are being lost (43). Interestingly though, no evidence for genome reduction has been reported for archaea. In our study, we estimated the genome sizes of MAGs based on the predicted degree of genome completeness evaluated with 146 lineage-specific SCG at a rank of phylum using CheckM (41). The “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” MAG ST15 MAG was excluded from this and all subsequent analyses, as it had comparatively low genome completeness (Table 1).

We found that the average estimated genome size of the five sponge-associated thaumarchaeal species (1.51 ± 0.34 Mbp) was significantly smaller than that of 15 terrestrial and marine free-living Thaumarchaeota (1.97 ± 0.65 Mbp) (Wilcox test, P value = 0.047; Fig. 3), but not when compared only to marine, free-living Thaumarchaeota (1.51 ± 0.19 Mbp) (Wilcox test, P value = 0.613). The former significant result is however likely due to the fact that marine Thaumarchaeota generally have smaller genomes than their terrestrial counterparts (44). Estimated genome sizes of individual sponge-associated species were also not significantly smaller than free-living ones, with “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus cymbastelus” having the largest of all marine genomes investigated here. This finding is consistent with recent work also noting a lack of significant reduction in genome size for archaeal endosymbionts of ciliates (45, 46).

FIG 3.

Genome length versus GC content for sponge-derived and free-living Thaumarchaeota. Genome length (in base pairs) versus GC content (as a percentage) are shown.

However, sponge-derived thaumarchaeal species had a significantly higher average GC content (53.75% ± 9.52%) than those of their 15 free-living counterparts (38.22% ± 6.98%) (Wilcox test, P value = 7.67E−04) or the 7 free-living marine Thaumarchaeota (33.40% ± 0.94%) (Wilcox test, P value = 3.11E−04). The GC contents for “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” (66.24% ± 1.05%), “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” (47.77% ± 0.21%), and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” (53.10% ± 0.16%) were also found separately to be higher than those of the seven free-living marine Thaumarchaeota, but with only marginal statistical support (Wilcox test, P value = 0.056 for each respective pairwise test). “Ca. UNitrosopumilus cymbastelus” had a GC content closer to those of free-living, marine Thaumarchaeota. GC enrichment has previously also been observed in obligate bacterial symbionts, such as “Candidatus Hodgkinia cicadicola” and “Candidatus Tremblaya princeps” of cicada (insects) (43, 47) and was assumed to be a result of GC directional mutational pressure during genome evolution (47). However, it has also been shown that high GC content is correlated to the adaptation to environmental stresses, such as nutrient and energy limitation (48). The mechanisms that give rise to the high GC content in the sponge-associated symbiotic Thaumarchaeota therefore require further investigation.

Analysis of host specificity showed generalist and specialist taxa.

The thaumarchaeal phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences from the current study and 19 sponge-derived thaumarchaeal sequences previously defined as sponge-specific sequence clusters by Simister et al. (5) showed that “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” and “Ca. Cenarchaeum symbiosum” belong to separate monophyletic clades comprised exclusively of sponge-specific 16S rRNA sequences (Fig. 1). This phylogenetic placement indicates that these two organisms might have an obligate sponge-associated lifestyle. In contrast, “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” did not cluster with previously described sponge-specific sequences but instead formed a distinct cluster with other free-living Thaumarchaeota. “Ca. UNitrosopumilus cymbastelus” was also closely related to sequences from free-living Thaumarchaeota.

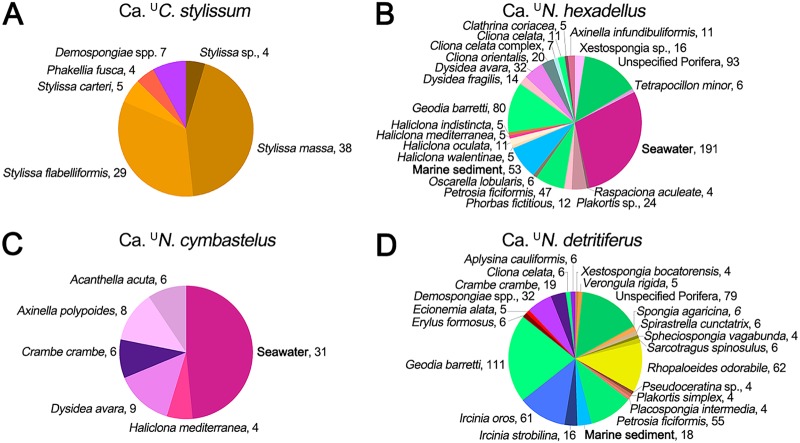

The 16S rRNA genes of “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus cymbastelus,” “Ca. Cenarchaeum symbiosum,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus,” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” were further searched against the Sponge Earth Microbiome Project (SEMP) database, which comprises 3,490 samples from more than 250 different sponge species and other marine habitats (http://www.spongeemp.com) (49). We allowed for single mismatches (i.e., 99% similarity) in the search against the zero-distance operational taxonomic units (zOTUs) generated by the Deblur algorithm used in the SEMP (49). “Ca. UC. stylissum” was found in 115 samples, which belonged exclusively to six sponge species, including four Stylissa species (Fig. 4; Table S2). “Ca. UN. hexadellus” and “Ca. UN. detritiferus” were detected in 969 and 722 samples, respectively, which belonged mainly to at least 20 sponge species. Both species were also found in some seawater and sediment samples analyzed in the SEMP, but the fact that they were enriched in sponges and had high genome coverage when assembled from the Hexadella microbial metagenomes (Table 1) suggests that they are symbionts of sponges.

FIG 4.

Enrichment of “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” (A), “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” (B), “Ca. UNitrosopumilus cymbastelus” (C), and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” (D) in samples of the Sponge Earth Microbiome Project. Enrichment was calculated using either presence/absence binomial tests or relative frequency-based rank sum tests. The values following the sample names represent the number of samples in which the archaeal species was detected.

Enrichment of thaumarchaeal species in different hosts and sample types. Enrichment analysis was calculated by default setting on the online server SEMP. Binomial P value test and rank sum (frequency aware) P value test were displayed. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (16.7KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Zhang et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

“Ca. UNitrosopumilus cymbastelus” was found in 87 samples, nearly half of which were seawater, while the remainder were recovered from five sponge species. Through 16S rRNA gene sequencing and fluorescence in situ hybridization visualization, “Ca. UN. cymbastelus” has previously been shown to be consistently present in Cymbastela concentrica, which was not analyzed in the SEMP (33). “Ca. Cenarchaeum symbiosum” was found in only one sample from the SEMP and thus no statistical support for host distribution could be obtained. The distributional patterns showed no overlap between “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus,” and “Ca. UN. cymbastelus” (Fig. 4; Fig. S2), and in most cases, each pair of thaumarchaeal species does not coexist within the same sponge species or sponge sample. The only exceptions are three sponge species (Cliona celata, Geodia barretti, and Petrosia ficiformis), where matches to both “Ca. UN. hexadellus” and “Ca. UN. detritiferus” were found.

Venn diagram of the distribution of sponge-associated Thaumarchaeota. Download FIG S2, TIF file, 1.1 MB (1.1MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2019 Zhang et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Together, these data show that “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” has a somewhat restricted host range by being predominantly found in Stylissa species and thus might have an obligate association with this sponge taxon. “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” occurred in a broader range of sponges, while “Ca. UNitrosopumilus cymbastelus” was frequently found outside sponges, indicating that these Thaumarchaeota have a more facultative relationship with particular sponge species or sponges in general.

A recent study demonstrated that sponge-associated symbiont communities are characterized by a combination of generalists and specialists (6). Generalists were defined as cosmopolitans that were not only present in a large number of sponge species but were also consistently present in a large fraction (>40%) of individuals of each host species. “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” clearly match this definition. “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” in contrast, appears to be more of a specialist, being restricted to a few closely related sponge taxa.

Functional analysis showed features indicating adaptation to the sponge environment.

To gain further insights into thaumarchaeal adaptation to a sponge-associated lifestyle, indicator analysis (50) was undertaken for the relative abundance of orthologous groups (OGs) of proteins. Comparison of OGs has been extensively used to investigate the evolution of organisms and their potential functional adaptation to the environment or particular lifestyles (9, 32). OGs from sponge-associated “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus,” and closely related free-living counterparts were compared. “Ca. UNitrosopumilus cymbastelus” and “Ca. Cenarchaeum symbiosum” were excluded from the indicator analysis, as they are represented only by single genomes, thus precluding statistical analyses.

The total 43,542 predicted protein sequences of the thaumarchaeal species investigated here clustered with 40% identity and more than 80% coverage into 14,780 OGs. MAGs of the sponge-associated “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” were compared to those from 15 free-living Thaumarchaeota (Table S1), and their combined 28,413 predicted protein sequences were contained in 4,748 OGs with at least two sequences per OG (Table 2). A total of 328 OGs in the indicator analysis had P values of <0.005 and were therefore indicative of either a sponge-associated or free-living lifestyle. Of these OGs, 248 were indicator OGs for sponge-associated genomes (Fig. S3), of which 100 could be assigned to archaeal Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (arCOGs) (51, 52). The “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” and the “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” data sets with 163 and 140 indicator OGs, respectively, had 129 and 104 indicator OGs for a sponge-associated lifestyle, of which 51 OGs for each species could be assigned to arCOG functions, respectively (Table 2; Fig. S3). The genomes of “Ca. UC. stylissum,” “Ca. UN. hexadellus,” and “Ca. UN. detritiferus” had 79, 34, and 36 indicator OGs with functions, respectively, which were significantly more abundant in all free-living thaumarchaeal genomes (Table 2; Fig. S3 and Table S3). These OGs with functions might be absent because they are no longer required for a sponge-associated lifestyle or simply due to the incompleteness of the MAGs.

TABLE 2.

Indicator analysis of OGs and functional properties of “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus”a

| Characteristic | Parameter value for proposed speciesb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| “Ca. UC. stylissum” |

“Ca. UN. hexadellus” |

“Ca. UN. dedritiferus” |

|

| General characteristics | |||

| Total no. of predicted protein sequences present in both SA and FL genomes |

28,413 | 28,851 | 28,822 |

| No. of OGs present in genomes | 4,748 | 4,631 | 4,601 |

| Indicator analysis | |||

| No. of indicator OGs | 328 | 163 | 140 |

| No. of indicator OGs for SA genomes | 248 | 129 | 104 |

| No. of indicator OGs assigned to arCOG functions for SA genomes | 100 | 51 | 51 |

| No. of indicator OGs for FL genomes | 80 | 34 | 36 |

| No. of indicator OGs assigned to arCOG functions for FL genomes | 79 | 34 | 36 |

Abbreviations: SA, sponge-associated; FL, free-living. P < 0.005 for two sponge-associated Thaumarchaeota and 15 free-living Thaumarchaeota.

The three proposed taxa are “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus detritiferus,” and “Candidatus UCenporiarchaeum stylissum.”

Indicator analysis of OGs for “Candidatus UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” (A), “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” (B), and “Candidatus UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” (C) analyzed in comparison to other free-living counterparts based on relative abundance data. A total of 328, 163, and 140 OGs are present in the heat map showing significant differences (P value <0.005) between different lifestyles for “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus,” respectively. The hierarchial trees of OGs and genomes are calculated based on Euclidian dissimilarities. Download FIG S3, TIF file, 2.7 MB (2.7MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2019 Zhang et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Comparison of the functional proteins and gene counts between sponge-associated “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus.” Functional proteins were listed according to different groups that were classified by their presence in different Thaumarchaeota species. The values on the right side are the gene number of functional proteins present in corresponding genomes. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.1 MB (146.2KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Zhang et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

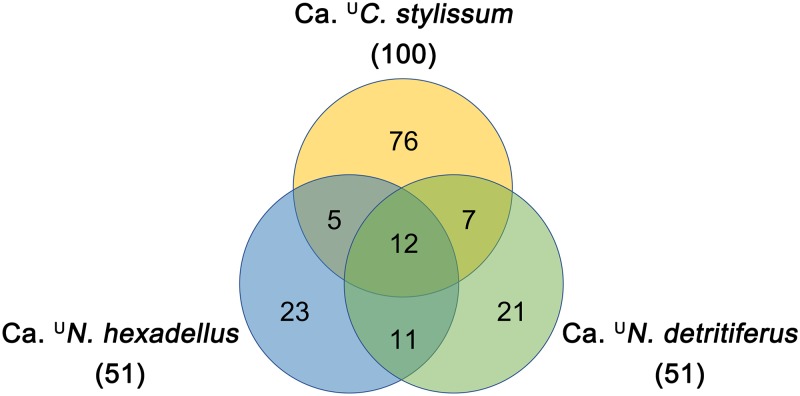

For all three species, OGs indicative of a sponge-associated lifestyle made up the majority (77.5% ± 4.7%) of all differential OGs (Fig. S3), providing support for the acquisition or enrichment of function in response to their particular symbiotic lifestyle. Twelve of these sponge-associated OGs, which could be assigned to arCOG functions, were found in all three species. “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” had more sponge-associated functions than “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” or “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” did (Fig. 5), indicating different degrees of functional or evolutionary adaptation to the sponge environment.

FIG 5.

Venn diagram showing sponge-associated functions found in three thaumarchaeal species analyzed in comparison to other free-living Thaumarchaeota.

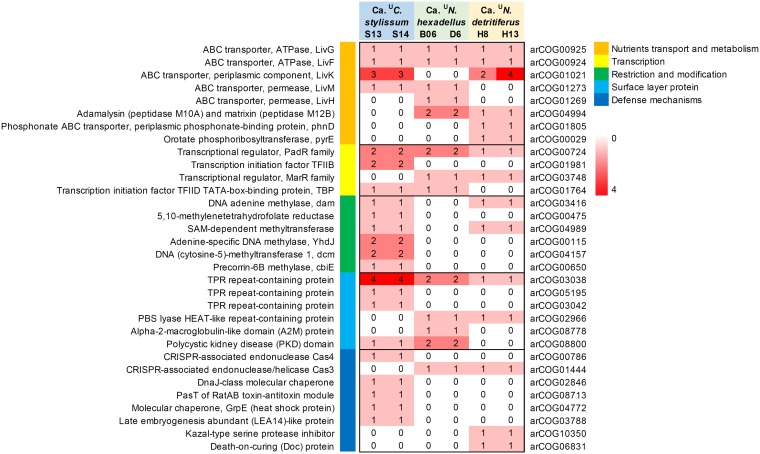

Shared OGs with functions involve metabolic and defense processes.

The 12 functions that were encoded by the indicator OG genes shared by “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” include Liv-type ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter ATPases (arCOG00924 and arCOG00925), a phenolic acid decarboxylase regulator (PadR)-like transcriptional regulator (arCOG00724), a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-containing protein (arCOG03038) and enzymes Cas3 and Cas4 (arCOG01444 or arCOG00786) (Fig. 6; Table S3).

FIG 6.

Comparison of sponge-associated functions in “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” using arCOG-based annotation. Details of additional functions are given in Table S3 in the supplemental material.

The cytoplasmic ATPases LivG (arCOG00925) and LivF (arCOG00924) belong to ABC-type transporters for branched-chain amino acids (Leucine-isoleucine-valine [Liv]) (53). These transporters also contain membrane-integrated permeases, for which different types (LivK, -M, and -H) were present in three sponge-associated Thaumarchaeota. In Escherichia coli, different types of permeases have been shown to contribute to the specificity of the transport system (54). In addition, “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” had high copy numbers for a unique OG that was annotated as a LivK-type periplasmic component (arCOG01201), which is involved in substrate binding during import (55). This indicates that import of branched-chain amino acids might be an import feature for sponge-associated Thaumarchaeota, which is consistent with other studies showing that ABC transporters might have a role in scavenging nutrients for bacteria within the sponge environment (12, 32, 33, 56, 57).

The PadR family (arCOG00724) comprises a diverse array of transcriptional regulators involved, for example, in detoxification of phenolic acids (58, 59), expression of multidrug efflux pumps (60), or virulence gene expression (61). Its exact role in sponge-associated Thaumarchaeota is therefore not clear. TPR-containing protein can mediate protein-protein interactions in eukaryotes (62) and might be used by sponge-associated bacteria to interfere with phagosome processing (63).

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and their associated Cas proteins constitute an adaptive immune system found in many prokaryotic genomes that provides protection against mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including viruses, transposable elements, and conjugative plasmids (64, 65). Cas3 has been proposed to play a key role in the CRISPR mechanism through direct cleavage of invasive nucleic acids (66, 67). Cas4 belongs to the RecB family of exonuclease, which is suggestive of DNA binding activity. The cas4 gene has been reported to be strictly associated with CRISPR elements (65) and appears to be less conserved than other cas genes, such as cas1 and cas2 (68, 69). In further support of the existence of CRISPR mechanisms in the sponge-associated Thaumarchaeota, we found CRISPR arrays and cas genes on the same genomic scaffolds for “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” MAG ST14 and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” MAG B06 (Fig. S4). CRISPRs and cas genes could also be found in the genomes of “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” but were located on different scaffolds, most likely due to incomplete assembly. Together, these results indicate the existence of some common features, such as amino acid transport as well as DNA defense, in the adaptation of thaumarchaeal species to the sponge environment. These findings are similar to recent findings that CRISPR and other defense-related features were found enriched in sponge-associated bacterial symbionts (70).

Schematic diagram of the CRISPR arrays and cas genes in “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” (A) and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” (B). They were found on scaffold 877 of “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” MAG ST14 and scaffold 7 of “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” MAG B06, respectively. cas genes are indicated with arrows in different colors, and the CRISPR array is shown with blue striped boxes. The numbers under genes indicate their DNA locus. Download FIG S4, TIF file, 0.8 MB (804.5KB, tif) .

Copyright © 2019 Zhang et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Shared and unique OGs of the generalist symbionts “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus.”

Almost half (44.7% ± 0.1%) of the functions encoded by sponge-associated OGs in “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” are the same as in “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus,” including a unique PBS lyase HEAT-like repeat domain (arCOG02966) (71–73). Proteins with this repeat domain have been reported to inactivate exogenous proteases (73) and therefore could mediate evasion of a host’s innate defense systems and resistance against phagocytosis. Both “Ca. UN. hexadellus” and “Ca. UN. detritiferus” also carried unique genes encoding components annotated as adamalysin (peptidase M10A) and matrixin (peptidase M12B) (arCOG04994), indicating that the two archaea have similar opportunities for the degradation of proteins and uptake of amino acids, which might be related to the existence of an extracellular protein matrix of their hosts.

“Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” and Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” also have unique, annotated OGs that discriminate their genomes. For example, “Ca. UN. hexadellus” contains a unique OG annotated as polycystic kidney disease (PKD) domain (arCOG08800) and another unique OG annotated as an ELP that consists of repeats of the alpha-2-macroglobulin-like domain (A2M) (arCOG08778). PKD domains have been previously detected in archaeal surface layer proteins (74), and both PKD and A2M have been suggested to have a role in interacting with the cell surface proteins of metazoans (73). An OG that was annotated as transcription initiation factor TFIID TATA box-binding protein (TBP) (arCOG01764) was also unique to “Ca. UN. hexadellus,” potentially playing a role in sensing and responding to the specific environmental conditions given in its sponge host.

As for features that distinguish “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” from “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” we found OGs that encode DNA adenine methylase (Dam) (arCOG03416) and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase (arCOG04989). Dams and SAM-dependent methyltransferases and associated cognate endonucleases form restriction-modification (R-M) systems that control the invasion of foreign DNA (75). Dams were enriched in both “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” and “Ca. UN. hexadellus” and were found next to the cognate endonuclease Endonuc-EcoRV (Pfam accession number PF09233) in “Ca. UC. stylissum” MAG ST14, strongly suggesting they are part of a functional R-M systems (76, 77). Protection against foreign DNA has previously been hypothesized to be an important feature of sponge-associated microbial communities that must maintain genomic integrity in an environment with a constant influx of biological material, including DNA and viruses, derived from the sponge’s filter-feeding activity (32, 70). “Ca. UN. detritiferus” also carries genes that encode unique OGs that were annotated as prophage death-on-curing (Doc) protein (arCOG06831) and the kazal-type serine protease inhibitor (arCOG10350), which have been reported to play important roles in bacterial stress response (78) and defense against proteinases from pathogenic bacteria (79). Together with the CRISPR mentioned above, these results imply a general need for defense mechanisms in “Ca. UN. detritiferus.” In addition, one OG annotated as a periplasmic binding protein of a phosphonate ABC transporter (PhnD) (arCOG01805) was exclusively found in “Ca. UN. detritiferus.” The ATPase (PhnC) and permease (PhnE) were also found in “Ca. UN. detritiferus” MAG H8. The phn genes are generally induced under phosphate limitation (80), perhaps indicating a potential adaptation of “Ca. UN. detritiferus” to a specific nutritional environment (i.e., limited phosphate) in Hexadella cf. detritifera.

Unique OGs with functional features in the specialist “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum.”

“Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” contains unique OGs that were annotated as methylases (YhdJ, arCOG00115; CbiE, arCOG00650) and methyltransferase (Dcm, arCOG04157) belonging to R-M systems, the heat shock protein GrpE (arCOG04772), and a DnaJ-class molecular chaperone (arCOG02846), a late embryogenesis abundant (LEA14)-like protein (arCOG03788), and proteins involved in a toxin-antitoxin (TA) module, including a persistence and stress resistance toxin PasT (arCOG08713). Heat shock proteins and chaperones protect other proteins from irreversible aggregation during synthesis and in times of cellular stress (81–83), and this has been postulated as an evolutionary adaptation in the symbiotic lifestyle of dinoflagellates (84). “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” has three OGs assigned to arCOG02846 (DnaJ-class molecular chaperone), of which one is unique to the organism. This unique copy could represent a specific functional adaptation or experience specific gene expression under conditions that are important for “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum.” “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” also has only one OG that was annotated as GrpE (arCOG04772), which is divergent from the OG with a gene that encodes GrpE in the other sponge-associated or free-living Thaumarchaea. It is unclear why this OG has diverged so much from those found in the other closely related archaea, but this could reflect a potential functional adaptation. The LEA14-like protein is thought to be associated with archaeal stress response and functions either in archaeal defense or by interacting with host signaling pathways (85). TA systems are prevalent in many bacterial genomes and contribute to biofilm and persister cell formation (86, 87). Specifically, in pathogenic Escherichia coli, the PasT of TA systems increased its antibiotic stress resistance (88). Such a defense mechanism might also be useful for sponge-associated Thaumarchaeota given a large number of chemical antagonists produced by sponges (89). Interestingly, “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum” also had a unique set of significantly enriched OGs that were annotated as TPRs (arCOG05195 and arCOG03042), which suggests a different kind of molecular interaction with the sponge host than what occurs in “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” (63).

Summary.

In our study, three new sponge-associated thaumarchaeal species were described, and we propose them to be specialist (“Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum”) or generalist (“Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus”) species based on their observed host distribution. The unique and shared genetic characteristics of “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” and “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus” have highlighted several genomic strategies for a sponge-associated lifestyle. Genomic traits found in all three species (e.g., CRISPR, TPRs) indicate a functional convergence reflecting general adaptation to the sponge environment. The unique characteristics for the specific thaumarchaeal taxa studied here highlight how generalists and specialists could be at different stages of evolutionary adaptation, employ different ecological strategies, and/or are exposed to different environmental conditions within the sponge hosts. Our study therefore provides new evolutionary and ecological insights into the symbiosis between Thaumarchaeota and marine sponges.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and sequencing.

Four individual deep-sea sponge specimens were collected from three stations in the North Atlantic Ocean (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material; map drawn with ODV software [90]). Sponge sample B0601MIN (B06) and H8 were collected from locations close to Mingulay, Scotland, and the Celtic Sea, France, respectively, while sponge sample D6ROC (D6) and H13 were sampled from the Irish Sea, Ireland. Phylogenetic analysis showed that these four sponges belong to the genus Hexadella but likely represent two different species within the genus with sample B06 and D6 being Hexadella detritifera and sample H8 and H13 belonging to Hexadella cf. detritifera (91, 122). Total genomic DNA was extracted from sponge samples using the MoBio PowerPlant DNA isolation kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (MO BIO Laboratories, CA, USA). We used a Covaris S series sonicator to shear DNA to ∼175-bp fragments and constructed metagenomic libraries using the Ovation Ultralow Library DR multiplex system (Nugen Redwood City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Metagenomic sequencing was conducted on the Illumina HiSeq 1000 platform with up to 2 × 113 bp chemistry at the W.M. Keck sequencing facility at the Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, MA, USA).

Station map in the North Atlantic Ocean. The map was drawn with the ODV software (90). Download FIG S5, TIF file, 1.3 MB (1.3MB, tif) .

Copyright © 2019 Zhang et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Three samples (S13, S14, and S15) of the sponge Stylissa flabelliformis were collected from the Davies Reef, Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Tissue samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C. Each sample was homogenized in collagenase and then centrifuged for microbial cell collection. Microbial community DNA was extracted with a Qiagen UltraClean Microbial DNA Isolation kit (92). Extracted DNA was further purified using the ZymoResearch (CA, USA) purification kit (Genome DNA clean and concentrator). Nextera XT library preparation was performed on all samples at the Ramaciotti Centre for Genomics (University of New South Wales, Australia), and samples were then sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform with 2 × 250-bp chemistry.

Further details about sample collection are presented in Table S4 and Fig. S5 in the supplemental material.

Details of sample collection. Download Table S4, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (13.7KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Zhang et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Metagenome-assembled genome reconstruction.

Metagenomic sequences obtained from individual sponges were analyzed separately to reconstruct archaeal metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) for comparative analysis. Paired-end reads were quality filtered and trimmed with Trimmomatic v.0.33 using the following parameters: “SLIDINGWINGDOW:6:30 MINGLEN:50” (93). Reads were assembled using IDBA_UD v.1.1.1 with the kmer size from 20 to 100 bp and an interval of 20 (94). Only contigs larger than 2.0 kbp were kept, and contig coverage was calculated by mapping reads back to the contigs using the end-to-end option of Bowtie2 v.2.2.9 (95). Metagenome binning was performed using both MetaBAT v.0.32.4 (96) and MyCC (97), and bins were then refined using Binning_refiner (98). MAG quality was assessed by CheckM based on the presence of 146 single-copy marker genes, which were grouped into 104 lineage-specific marker sets from 207 archaeal genomes (41). The genome size was estimated by dividing the bin size by its estimated completeness. High heterogeneity was evident in some of the bins due to the high coverage (e.g., the sequencing depth of data set D6 was about 361×). In these cases, bins with high quality were obtained by subsampling the metagenomic reads to reduce the coverage followed by assembly and binning as described above.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences were reconstructed from metagenomic reads using MATAM (40), and their taxonomical information was obtained by alignment to the SILVA database v1.2.11 (99, 100). Reconstructed thaumarchaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences were added to the MAG, if they had a sequence similarity of ≥98.6% (101) and an alignment length of more than 400 bp with any scaffold within the MAG. All aligned thaumarchaeal 16S rRNA genes were then subjected to a BLASTN search (102, 103) against the nonredundant nucleotide (NT) database at the NCBI on 2 December 2017, and top hits with closed genomes were aligned in order to determine sequence similarities (104, 105). In addition, another sponge-associated thaumarchaeal genome bin (Ga0078905) with corresponding 16S rRNA genes assembled from metagenomic data sets from the sponge Cymbastela concentrica was included (33). 16S rRNA gene sequences of >1,000 bp were aligned using MAFFT v7.310 (106), and a maximum-likelihood tree was calculated using RAxML v.8.2.10 with a GTRGAMMA model and 1,000 bootstraps (107). The tree was visualized using iTOL (108) and rooted with the sequence of two Aigarchaeota (“Candidatus Caldiarchaeum subterraneum” NC_022786.1 and an unclassified Aigarchaeota Ga0180309_101) and one unclassified Thaumarchaeota (Ga0181444_1001) as an outgroup (109, 110). The 16S rRNA genes of the new MAGs were also searched against the Sponge Earth Microbiome Project (SEMP) database (http://www.spongeemp.com) (49), and the search results were manually curated to remove hits against biofilm samples, whose exact nature were unclear.

For further taxonomic classification, pairwise average amino acid identity (AAI) distance between new MAGs and 74 thaumarchaeal reference genomes was calculated with the Microbial Genomes Atlas (111). Pairwise AAI distance between the new MAGs and the 16 most similar closed reference genomes was also calculated using CompareM (https://github.com/dparks1134/CompareM). The SCG tree for all input genomes was inferred from the concatenation of 122 archaeal single-copy proteins identified as being present in ≥90% of archaeal genomes and, when present, being present in a single copy in ≥95% of the genomes (112). Predicted protein sequences for the input genomes were searched against the PFAM v31.0 (113) and TIGRFAM v14.0 (114) hmm profiles of these SCG proteins using HMMER v3.1b2 (115). Protein sequences for each hmm profile were then individually aligned with MAFFT v7.310 and concatenated into a multiple-sequence alignment (MSA). A phylogenetic tree was then generated by RAxML v.8.2.10 with a PROTGAMMAWAG model and 1,000 bootstraps and visualized as well as rooted as described above.

Gene annotation and comparison.

Prodigal, as implemented in Prokka, was used to predict open reading frames (ORF) in the MAGs using the “metagenome” setting and specifying the kingdom as “Archaea” (116, 117). All predicted protein sequences were clustered into orthologous groups (OGs) using the OrthoMCL v1.4 clustering algorithm (118) as implemented in the program get_homologues v18092017 (119). Bidirectional BLAST searches were filtered with an E value of 10−05 as well as >40% alignment identity over 80% alignment coverage, which has been demonstrated to have a probability of >90% that the sequences in OGs are also homologous (120). The longest sequence in each OG is then used for functional annotation. OGs that are characteristic of sponge-associated and free-living lifestyle were identified using indicator analysis on relative abundance data (50). Abundance data for OGs were also visualized using the R package “pheatmap” (121). OGs that displayed significant differences between lifestyles were further annotated by searching them with BLASTP and an E value of 10−4 against the archaeal Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (arCOGs) database released in December 2014 (51, 52). Some functional names of clusters were corrected by annotation results against the Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COGs) and KEGG Orthology (KO) databases.

Data availability.

Sequences from this project have been deposited at the GenBank database under the genome accession numbers RHFA00000000, RHEZ00000000, and RHEY00000000 for “Ca. UCenporiarchaeum stylissum,” RHFD00000000 and RHFE00000000 for “Ca. UNitrosopumilus hexadellus,” and RHFB00000000 and RHFC00000000 for “Ca. UNitrosopumilus detritiferus.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research is funded by the Australian Research Council. Shan Zhang (201708200017) and Weizhi Song (201508200019) were funded by the China Scholarship Council. We thank A. Murat Eren for supporting the metagenomic sequencing of Hexadella sponges through his Frank R. Lillie Research Innovation Award.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor MW, Radax R, Steger D, Wagner M. 2007. Sponge-associated microorganisms: evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71:295–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster NS, Cobb RE, Negri AP. 2008. Temperature thresholds for bacterial symbiosis with a sponge. ISME J 2:830–842. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu P, Li QZ, Wang GY. 2008. Unique microbial signatures of the alien Hawaiian marine sponge Suberites zeteki. Microb Ecol 55:406–414. doi: 10.1007/s00248-007-9285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hentschel U, Piel J, Degnan SM, Taylor MW. 2012. Genomic insights into the marine sponge microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:641–654. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simister RL, Deines P, Botté ES, Webster NS, Taylor MW. 2012. Sponge-specific clusters revisited: a comprehensive phylogeny of sponge-associated microorganisms. Environ Microbiol 14:517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas T, Moitinho-Silva L, Lurgi M, Björk JR, Easson C, Astudillo-García C, Olson JB, Erwin PM, López-Legentil S, Luter H, Chaves-Fonnegra A, Costa R, Schupp PJ, Steindler L, Erpenbeck D, Gilbert J, Knight R, Ackermann G, Lopez VJ, Taylor MW, Thacker RW, Montoya JM, Hentschel U, Webster NS. 2016. Diversity, structure and convergent evolution of the global sponge microbiome. Nat Commun 7:11870. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao ZM, Wang Y, Tian RM, Wong YH, Batang ZB, Al-Suwailem AM, Bajic VB, Qian PY. 2014. Symbiotic adaptation drives genome streamlining of the cyanobacterial sponge symbiont “Candidatus Synechococcus spongiarum.” mBio 5:e00079-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00079-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgsdorf I, Slaby BM, Handley KM, Haber M, Blom J, Marshall CW, Gilbert JA, Hentschel U, Steindler L. 2015. Lifestyle evolution in cyanobacterial symbionts of sponges. mBio 6:e00391-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00391-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Díez‐Vives C, Esteves AI, Costa R, Nielsen S, Thomas T. 2018. Detecting signatures of a sponge‐associated lifestyle in bacterial genomes. Environ Microbiol Rep 10:433–443. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamke J, Rinke C, Schwientek P, Mavromatis K, Ivanova N, Sczyrba A, Woyke T, Hentschel U. 2014. The candidate phylum Poribacteria by single-cell genomics: new insights into phylogeny, cell-compartmentation, eukaryote-like repeat proteins, and other genomic features. PLoS One 9:e87353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karimi E, Slaby BM, Soares AR, Blom J, Hentschel U, Costa R. 2018. Metagenomic binning reveals versatile nutrient cycling and distinct adaptive features in alphaproteobacterial symbionts of marine sponges. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 94:fiy074. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian RM, Wang Y, Bougouffa S, Gao ZM, Cai L, Bajic V, Qian PY. 2014. Genomic analysis reveals versatile heterotrophic capacity of a potentially symbiotic sulfur-oxidizing bacterium in sponge. Environ Microbiol 16:3548–3561. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian RM, Zhang W, Cai L, Wong YH, Ding W, Qian PY. 2017. Genome reduction and microbe-host interactions drive adaptation of a sulfur-oxidizing bacterium associated with a cold seep sponge. mSystems 2:e00184-16. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00184-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker CB, de la Torre JR, Klotz MG, Urakawa H, Pinel N, Arp DJ, Brochier-Armanet C, Chain PSG, Chan PP, Gollabgir A, Hemp J, Hugler M, Karr EA, Konneke M, Shin M, Lawton TJ, Lowe T, Martens-Habbena W, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Lang D, Sievert SM, Rosenzweig AC, Manning G, Stahl DA. 2010. Nitrosopumilus maritimus genome reveals unique mechanisms for nitrification and autotrophy in globally distributed marine crenarchaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:8818–8823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913533107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santoro AE, Dupont CL, Richter RA, Craig MT, Carini P, McIlvin MR, Yang Y, Orsi WD, Moran DM, Saito MA. 2015. Genomic and proteomic characterization of “Candidatus Nitrosopelagicus brevis”: an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from the open ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:1173–1178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416223112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayer B, Vojvoda J, Offre P, Alves RJE, Elisabeth NH, Garcia JAL, Volland JM, Srivastava A, Schleper C, Herndl GJ. 2016. Physiological and genomic characterization of two novel marine thaumarchaeal strains indicates niche differentiation. ISME J 10:1051–1063. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahlgren NA, Chen YY, Needham DM, Parada AE, Sachdeva R, Trinh V, Chen T, Fuhrman JA. 2017. Genome and epigenome of a novel marine Thaumarchaeota strain suggest viral infection, phosphorothioation DNA modification and multiple restriction systems. Environ Microbiol 19:2434–2452. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spang A, Poehlein A, Offre P, Zumbrägel S, Haider S, Rychlik N, Nowka B, Schmeisser C, Lebedeva EV, Rattei T, Böhm C, Schmid M, Galushko A, Hatzenpichler R, Weinmaier T, Daniel R, Schleper C, Spieck E, Streit W, Wagner M. 2012. The genome of the ammonia-oxidizing Candidatus Nitrososphaera gargensis: insights into metabolic versatility and environmental adaptations. Environ Microbiol 14:3122–3145. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sauder LA, Engel K, Lo CC, Chain P, Neufeld JD. 2018. “Candidatus Nitrosotenuis aquariensis,” an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from a freshwater aquarium biofilter. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e01430-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01430-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li YY, Ding K, Wen XH, Zhang B, Shen B, Yang YF. 2016. A novel ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from wastewater treatment plant: its enrichment, physiological and genomic characteristics. Sci Rep 6:23747. doi: 10.1038/srep23747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sauder LA, Albertsen M, Engel K, Schwarz J, Nielsen PH, Wagner M, Neufeld JD. 2017. Cultivation and characterization of Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus exaquare, an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from a municipal wastewater treatment system. ISME J 11:1142–1157. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehtovirta-Morley LE, Stoecker K, Vilcinskas A, Prosser JI, Nicol GW. 2011. Cultivation of an obligate acidophilic ammonia oxidizer from a nitrifying acid soil. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:15892–15897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107196108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tourna M, Stieglmeier M, Spang A, Könneke M, Schintlmeister A, Urich T, Engel M, Schloter M, Wagner M, Richter A, Schleper C. 2011. Nitrososphaera viennensis, an ammonia oxidizing archaeon from soil. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:8420–8425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013488108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhalnina KV, Dias R, Leonard MT, De Quadros PD, Camargo FAO, Drew JC, Farmerie WG, Daroub SH, Triplett EW. 2014. Genome sequence of Candidatus Nitrososphaera evergladensis from group I.1b enriched from Everglades soil reveals novel genomic features of the ammonia-oxidizing archaea. PLoS One 9:e101648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung MY, Kim JG, Damsté JSS, Rijpstra WIC, Madsen EL, Kim SJ, Hong H, Si OJ, Kerou M, Schleper C, Rhee SK. 2016. A hydrophobic ammonia-oxidizing archaeon of the Nitrosocosmicus clade isolated from coal tar-contaminated sediment. Environ Microbiol Rep 8:983–992. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park SJ, Kim JG, Jung MY, Kim SJ, Cha IT, Ghai R, Martin-Cuadrado AB, Rodriguez-Valera F, Rhee SK. 2012. Draft genome sequence of an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon, “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus sediminis” AR2, from Svalbard in the Arctic Circle. J Bacteriol 194:6948–6949. doi: 10.1128/JB.01857-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park SJ, Kim JG, Jung MY, Kim SJ, Cha IT, Kwon K, Lee JH, Rhee SK. 2012. Draft genome sequence of an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon, “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus koreensis” AR1, from marine sediment. J Bacteriol 194:6940–6941. doi: 10.1128/JB.01869-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preston CM, Wu KY, Molinski TF, DeLong EF. 1996. A psychrophilic crenarchaeon inhabits a marine sponge: Cenarchaeum symbiosum gen. nov., sp. nov. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:6241–6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schleper C, DeLong EF, Preston CM, Feldman RA, Wu KY, Swanson RV. 1998. Genomic analysis reveals chromosomal variation in natural populations of the uncultured psychrophilic archaeon Cenarchaeum symbiosum. J Bacteriol 180:5003–5009. https://jb.asm.org/content/180/19/5003.short. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallam SJ, Konstantinidis KT, Putnam N, Schleper C, Watanabe Y-I, Sugahara J, Preston C, de la Torre J, Richardson PM, DeLong EF. 2006. Genomic analysis of the uncultivated marine crenarchaeote Cenarchaeum symbiosum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:18296–18301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608549103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmes B, Blanch H. 2007. Genus-specific associations of marine sponges with group I crenarchaeotes. Mar Biol 150:759–772. doi: 10.1007/s00227-006-0361-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan L, Reynolds D, Liu M, Stark M, Kjelleberg S, Webster NS, Thomas T. 2012. Functional equivalence and evolutionary convergence in complex communities of microbial sponge symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:E1878–E1887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203287109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moitinho-Silva L, Díez-Vives C, Batani G, Esteves AI, Jahn MT, Thomas T. 2017. Integrated metabolism in sponge-microbe symbiosis revealed by genome-centered metatranscriptomics. ISME J 11:1651–1666. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radax R, Hoffmann F, Rapp HT, Leininger S, Schleper C. 2012. Ammonia‐oxidizing archaea as main drivers of nitrification in cold‐water sponges. Environ Microbiol 14:909–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radax R, Rattei T, Lanzen A, Bayer C, Rapp HT, Urich T, Schleper C. 2012. Metatranscriptomics of the marine sponge Geodia barretti: tackling phylogeny and function of its microbial community. Environ Microbiol 14:1308–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerou M, Offre P, Valledor L, Abby SS, Melcher M, Nagler M, Weckwerth W, Schleper C. 2016. Proteomics and comparative genomics of Nitrososphaera viennensis reveal the core genome and adaptations of archaeal ammonia oxidizers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E7937–E7946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601212113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stieglmeier M, Mooshammer M, Kitzler B, Wanek W, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S, Richter A, Schleper C. 2014. Aerobic nitrous oxide production through N-nitrosating hybrid formation in ammonia-oxidizing archaea. ISME J 8:1135–1146. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kozlowski JA, Stieglmeier M, Schleper C, Klotz MG, Stein LY. 2016. Pathways and key intermediates required for obligate aerobic ammonia-dependent chemolithotrophy in bacteria and Thaumarchaeota. ISME J 10:1836–1845. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Damsté JSS, Rijpstra WIC, Hopmans EC, Jung M-Y, Kim J-G, Rhee S-K, Stieglmeier M, Schleper C. 2012. Intact polar and core glycerol dibiphytanyl glycerol tetraether lipids of group I.1a and I.1b Thaumarchaeota in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:6866–6874. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01681-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pericard P, Dufresne Y, Couderc L, Blanquart S, Touzet H. 2018. MATAM: reconstruction of phylogenetic marker genes from short sequencing reads in metagenomes. Bioinformatics 34:585–591. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. 2015. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res 25:1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konstantinidis KT, Rosselló-Móra R, Amann R. 2017. Uncultivated microbes in need of their own taxonomy. ISME J 11:2399–2406. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCutcheon JP, Moran NA. 2012. Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:13–26. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kellner S, Spang A, Offre P, Szöllősi GJ, Petitjean C, Williams TA. 2018. Genome size evolution in the Archaea. Emerg Top Life Sci 2:595–605. doi: 10.1042/ETLS20180021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beinart RA, Rotterová J, Čepička I, Gast RJ, Edgcomb VP. 2018. The genome of an endosymbiotic methanogen is very similar to those of its free-living relatives. Environ Microbiol 20:2538–2551. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lind AE, Lewis WH, Spang A, Guy L, Embley TM, Ettema T. 2018. Genomes of two archaeal endosymbionts show convergent adaptations to an intracellular lifestyle. ISME J 12:2655–2667. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0207-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCutcheon JP, McDonald BR, Moran NA. 2009. Origin of an alternative genetic code in the extremely small and GC-rich genome of a bacterial symbiont. PLoS Genet 5:e1000565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mann S, Chen YP. 2010. Bacterial genomic G+C composition-eliciting environmental adaptation. Genomics 95:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moitinho-Silva L, Nielsen S, Amir A, Gonzalez A, Ackermann GL, Cerrano C, Astudillo-Garcia C, Easson C, Sipkema D, Liu F, Steinert G, Kotoulas G, McCormack GP, Feng G, Bell JJ, Vicente J, Björk JR, Montoya JM, Olson JB, Reveillaud J, Steindler L, Pineda MC, Marra MV, Ilan M, Taylor MW, Polymenakou P, Erwin PM, Schupp PJ, Simister RL, Knight R, Thacker RW, Costa R, Hill RT, Lopez-Legentil S, Dailianis T, Ravasi T, Hentschel U, Li Z, Webster NS, Thomas T. 2017. The sponge microbiome project. GigaScience 6:gix077. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cáceres MD, Legendre P. 2009. Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 90:3566–3574. doi: 10.1890/08-1823.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolf YI, Makarova KS, Yutin N, Koonin EV. 2012. Updated clusters of orthologous genes for Archaea: a complex ancestor of the Archaea and the byways of horizontal gene transfer. Biol Direct 7:46. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. 2015. Archaeal clusters of orthologous genes (arCOGs): an update and application for analysis of shared features between Thermococcales, Methanococcales, and Methanobacteriales. Life 5:818–840. doi: 10.3390/life5010818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karpowich N, Martsinkevich O, Millen L, Yuan YR, Dai PL, MacVey K, Thomas PJ, Hunt JF. 2001. Crystal structures of the MJ1267 ATP binding cassette reveal an induced-fit effect at the ATPase active site of an ABC transporter. Structure 9:571–586. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00617-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams MD, Wagner LM, Graddis TJ, Landick R, Antonucci TK, Gibson AL, Oxender DL. 1990. Nucleotide sequence and genetic characterization reveal six essential genes for the LIV-I and LS transport systems of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 265:11436–11443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilkens S. 2015. Structure and mechanism of ABC transporters. F1000Prime Rep 7:14. doi: 10.12703/P7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu M, Fan L, Zhong L, Kjelleberg S, Thomas T. 2012. Metaproteogenomic analysis of a community of sponge symbionts. ISME J 6:1515–1525. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gauthier MEA, Watson JR, Degnan SM. 2016. Draft genomes shed light on the dual bacterial symbiosis that dominates the microbiome of the coral reef sponge Amphimedon queenslandica. Front Mar Sci 3:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barthelmebs L, Lecomte B, Divies C, Cavin JF. 2000. Inducible metabolism of phenolic acids in Pediococcus pentosaceus is encoded by an autoregulated operon which involves a new class of negative transcriptional regulator. J Bacteriol 182:6724–6731. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6724-6731.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gury J, Barthelmebs L, Tran NP, Divies C, Cavin JF. 2004. Cloning, deletion, and characterization of PadR, the transcriptional repressor of the phenolic acid decarboxylase-encoding padA gene of Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:2146–2153. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2146-2153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huillet E, Velge P, Vallaeys T, Pardon P. 2006. LadR, a new PadR-related transcriptional regulator from Listeria monocytogenes, negatively regulates the expression of the multidrug efflux pump MdrL. FEMS Microbiol Lett 254:87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cotter PA, Stibitz S. 2007. c-di-GMP-mediated regulation of virulence and biofilm formation. Curr Opin Microbiol 10:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lamb JR, Tugendreich S, Hieter P. 1995. Tetratrico peptide repeat interactions: to TPR or not to TPR? Trends Biochem Sci 20:257–259. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)89037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reynolds D, Thomas T. 2016. Evolution and function of eukaryotic-like proteins from sponge symbionts. Mol Ecol 25:5242–5253. doi: 10.1111/mec.13812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bolotin A, Quinquis B, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD. 2005. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology 151:2551–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haft DH, Selengut J, Mongodin EF, Nelson KE. 2005. A guild of 45 CRISPR-associated (Cas) protein families and multiple CRISPR/Cas subtypes exist in prokaryotic genomes. PLoS Comput Biol 1:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beloglazova N, Petit P, Flick R, Brown G, Savchenko A, Yakunin AF. 2011. Structure and activity of the Cas3 HD nuclease MJ0384, an effector enzyme of the CRISPR interference. EMBO J 30:4616–4627. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sinkunas T, Gasiunas G, Fremaux C, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. 2011. Cas3 is a single-stranded DNA nuclease and ATP-dependent helicase in the CRISPR/Cas immune system. EMBO J 30:1335–1342. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Louwen R, Staals RH, Endtz HP, van Baarlen P, van der Oost J. 2014. The role of CRISPR-Cas systems in virulence of pathogenic bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 78:74–88. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00039-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nam KH, Kurinov I, Ke A. 2011. Crystal structure of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated Csn2 protein revealed Ca2+-dependent double-stranded DNA binding activity. J Biol Chem 286:30759–30768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.256263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Horn H, Slaby BM, Jahn MT, Bayer K, Moitinho-Silva L, Förster F, Abdelmohsen UR, Hentschel U. 2016. An enrichment of CRISPR and other defense-related features in marine sponge-associated microbial metagenomes. Front Microbiol 7:1751. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sottrup-Jensen L. 1989. Alpha-macroglobulins: structure, shape, and mechanism of proteinase complex formation. J Biol Chem 264:11539–11542. http://www.jbc.org/content/264/20/11539.short. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Andrade MA, Petosa C, O’Donoghue SI, Müller CW, Bork P. 2001. Comparison of ARM and HEAT protein repeats1. J Mol Biol 309:1–18. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Armstrong PB. 2006. Proteases and protease inhibitors: a balance of activities in host-pathogen interaction. Immunobiology 211:263–281. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jing H, Takagi J, Liu JH, Lindgren S, Zhang RG, Joachimiak A, Wang JH, Springer TA. 2002. Archaeal surface layer proteins contain beta propeller, PKD, and beta helix domains and are related to metazoan cell surface proteins. Structure 10:1453–1464. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00840-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schouler C, Clier F, Lerayer AL, Ehrlich SD, Chopin MC. 1998. A type IC restriction-modification system in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol 180:407–411. https://jb.asm.org/content/180/2/407.short. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murphy J, Mahony J, Ainsworth S, Nauta A, van Sinderen D. 2013. Bacteriophage orphan DNA methyltransferases: insights from their bacterial origin, function, and occurrence. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:7547–7555. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02229-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Payelleville A, Lanois A, Gislard M, Dubois E, Roche D, Cruveiller S, Givaudan A, Brillard J. 2017. DNA adenine methyltransferase (Dam) overexpression impairs Photorhabdus luminescens motility and virulence. Front Microbiol 8:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Garcia-Pino A, Zenkin N, Loris R. 2014. The many faces of Fic: structural and functional aspects of Fic enzymes. Trends Biochem Sci 39:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Somprasong N, Rimphanitchayakit V, Tassanakajon A. 2006. A five-domain Kazal-type serine proteinase inhibitor from black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon and its inhibitory activities. Dev Comp Immunol 30:998–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gebhard S, Tran SL, Cook GM. 2006. The Phn system of Mycobacterium smegmatis: a second high-affinity ABC-transporter for phosphate. Microbiology 152:3453–3465. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schröder H, Langer T, Hartl FU, Bukau B. 1993. DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE form a cellular chaperone machinery capable of repairing heat-induced protein damage. EMBO J 12:4137–4144. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fink AL. 1999. Chaperone-mediated protein folding. Physiol Rev 79:425–449. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dubern JF, Lagendijk EL, Lugtenberg BJJ, Bloemberg GV. 2005. The heat shock genes dnaK, dnaJ, and grpE are involved in regulation of putisolvin biosynthesis in Pseudomonas putida PCL1445. J Bacteriol 187:5967–5976. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.5967-5976.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aranda M, Li Y, Liew YJ, Baumgarten S, Simakov O, Wilson MC, Piel J, Ashoor H, Bougouffa S, Bajic VB, Ryu T, Ravasi T, Bayer T, Micklem G, Kim H, Bhak J, LaJeunesse TC, Voolstra CR. 2016. Genomes of coral dinoflagellate symbionts highlight evolutionary adaptations conducive to a symbiotic lifestyle. Sci Rep 6:39734. doi: 10.1038/srep39734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ciccarelli FD, Bork P. 2005. The WHy domain mediates the response to desiccation in plants and bacteria. Bioinformatics 21:1304–1307. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Magnuson RD. 2007. Hypothetical functions of toxin-antitoxin systems. J Bacteriol 189:6089–6092. doi: 10.1128/JB.00958-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang X, Wood TK. 2011. Toxin-antitoxin systems influence biofilm and persister cell formation and the general stress response. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:5577–5583. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05068-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Norton JP, Mulvey MA. 2012. Toxin-antitoxin systems are important for niche-specific colonization and stress resistance of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002954. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thomas TRA, Devanand PK, Ponnapakkam A, Loka B. 2010. Marine drugs from sponge-microbe association—a review. Mar Drugs 8:1417–1468. doi: 10.3390/md8041417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schlitzer R. 2018. Ocean Data View. odv.awi.de.

- 91.Reveillaud J, Remerie T, van Soest R, Erpenbeck D, Cárdenas P, Derycke S, Xavier JR, Rigaux A, Vanreusel A. 2010. Species boundaries and phylogenetic relationships between Atlanto-Mediterranean shallow-water and deep-sea coral associated Hexadella species (Porifera, Ianthellidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol 56:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bennett HM. 2017. Climate change and tropical sponges: the effect of elevated pCO2 and temperature on the sponge holobiont. PhD thesis. Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/6240.

- 93.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peng Y, Leung HCM, Yiu SM, Chin F. 2012. IDBA-UD: a de novo assembler for single-cell and metagenomic sequencing data with highly uneven depth. Bioinformatics 28:1420–1428. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kang DD, Froula J, Egan R, Wang Z. 2015. MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. PeerJ 3:e1165. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lin HH, Liao YC. 2016. Accurate binning of metagenomic contigs via automated clustering sequences using information of genomic signatures and marker genes. Sci Rep 6:24175. doi: 10.1038/srep24175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Song WZ, Thomas T. 2017. Binning_refiner: improving genome bins through the combination of different binning programs. Bioinformatics 33:1873–1875. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. 2012. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yilmaz P, Parfrey LW, Yarza P, Gerken J, Pruesse E, Quast C, Schweer T, Peplies J, Ludwig W, Glöckner FO. 2014. The SILVA and “all-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D643–D648. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Stackebrandt E, Ebers J. 2006. Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol Today 33:152–155. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. 2007. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 35:D61–D65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Johnson M, Zaretskaya I, Raytselis Y, Merezhuk Y, McGinnis S, Madden TL. 2008. NCBI BLAST: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W5–W9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Letunic I, Bork P. 2016. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hua ZS, Qu YN, Zhu Q, Zhou EM, Qi YL, Yin YR, Rao YZ, Tian Y, Li YX, Liu L, Castelle CJ, Hedlund BP, Shu WS, Knight R, Li WJ. 2018. Genomic inference of the metabolism and evolution of the archaeal phylum Aigarchaeota. Nat Commun 9:2832. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05284-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]