Abstract

Arene hydrogenation provides direct access to saturated carbo‐ and heterocycles and thus its strategic application may be used to shorten synthetic routes. This powerful transformation is widely applied in industry and is expected to facilitate major breakthroughs in the applied sciences. The ability to overcome aromaticity while controlling diastereo‐, enantio‐, and chemoselectivity is central to the use of hydrogenation in the preparation of complex molecules. In general, the hydrogenation of multisubstituted arenes yields predominantly the cis isomer. Enantiocontrol is imparted by chiral auxiliaries, Brønsted acids, or transition‐metal catalysts. Recent studies have demonstrated that highly chemoselective transformations are possible. Such methods and the underlying strategies are reviewed herein, with an emphasis on synthetically useful examples that employ readily available catalysts.

Keywords: arene hydrogenation, chemoselectivity, cycloalkanes, heterocycles, stereoselectivity

1. Introduction

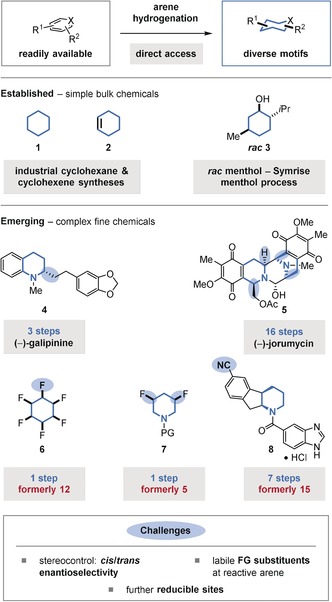

Arene hydrogenation transforms aromatic substrates into saturated carbo‐ and heterocycles. Classical methods, such as aromatic substitutions, condensations, and cross‐coupling reactions, provide access to innumerable arene and heteroarene substrates. In turn, arene hydrogenation provides the most direct, retrosynthetically simple route to a vast, divergent range of cyclic saturated motifs (Figure 1). Its strategic value is reflected in a number of current multi‐thousand ton scale industrial applications, such as the hydrogenation of benzene to cyclohexane (1)1 or cyclohexene (2)2 for nylon production, or the hydrogenation of thymol to (racemic) menthol (rac‐3) in the Symrise menthol process.3 Arene hydrogenation is an important step in the valorization of biomass‐derived platform chemicals such as furfural.4 Furthermore, arene hydrogenation and dehydrogenation are the key steps in the operation of liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs).5 The utilization of arene hydrogenation to access saturated functional molecules in the fine‐chemical sector is gaining momentum. For example, the enantioselective hydrogenation of quinolines has enabled efficient access to enantioenriched tetrahydroquinoline alkaloids such as (−)‐galipinine (4).6 A beautiful recent example would be the synthesis of (−)‐jorunnamycin A and (−)‐jorumycin (5) by the Stoltz group, whereby the core was constructed through an enantioselective isoquinoline hydrogenation‐cyclization, thereby introducing a high level of complexity in a single operation.7 Likewise, arene hydrogenations have provided notable synthetic shortcuts to all‐cis‐(multi‐)fluorinated cycloalkanes (e.g. 6)8 and piperidines (e.g. 7).9 The former motif (6) is of interest in materials science for its high polarity; the latter (7) combines two abundant design elements of medicinal chemistry. The chemo‐ and enantioselective hydrogenation of pyridines is the key step within a concise, multikilogram synthesis (7 steps, 38 % overall yield) of a promising therapeutic against Type 2 diabetes (8).10 However, the implementation of this transformation towards a given target must satisfy three important conditions:

Figure 1.

Arene hydrogenation provides direct access to diverse carbo‐ and heterocycle motifs.

Reactivity: in contrast to the established hydrogenation of other unsaturated moieties such as alkenes,11 ketones,12 and imines/enamines,13 the hydrogenation of arenes is hindered by the added kinetic barrier resulting from the aromatic stabilization energy.

Stereoselectivity: the hydrogenation of multisubstituted arenes may form several product diastereomers; in general, the cis isomer is favored. Furthermore, substituted saturated carbo‐ and heterocycles are often chiral.

Chemoselectivity: elaborate substrates often exhibit competing side reactions—for example, concurrent hydrogenation of more reductively labile units, such as alkenes, or hydrodefunctionalizations.

Arguably the kinetic barrier was surmounted in 1901, with the first report on the hydrogenation of benzene by Sabatier and Senderens.14 Today, the hydrogenation of almost all known arene and heteroarene motifs can be achieved using a variety of available catalyst systems. Such catalyst systems include both homogeneous metal complexes and heterogeneous catalysts, such as metal (nano‐)particles and surface‐supported catalysts.15a–15d Nevertheless, the low reactivity of a particular arene substrate often constrains the selection of catalyst systems, especially for strongly stabilized benzene derivatives, and hence may lead to alternative challenges such as enantio‐ or chemoselectivity. The development of transformations with predictable selectivity remains demanding and research into such reactions is an emerging field. The objectives of this Review are to discuss these recent efforts from the perspective of the organic chemist, to help the reader to judge whether or not a desired hydrogenation reaction is facile, and to suggest which catalyst system should be tried preferentially. A perspective for future work will be outlined in the process. Such a review cannot be comprehensive; recent reviews have been published focusing on various aspects of arene hydrogenation15 or dearomatization reactions in a broader sense.16

2. Stereoselective Arene Hydrogenation

2.1. Diastereoselective Arene Hydrogenation

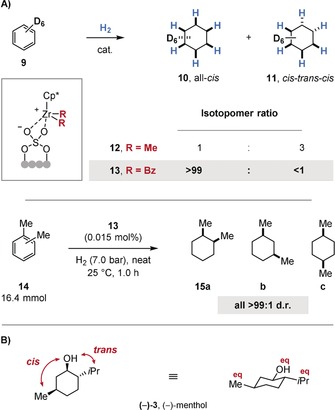

The hydrogenation of disubstituted arenes may generate two diastereomers of the saturated product. Arene hydrogenation generally proceeds with high cis selectivity, although the trans isomer is usually thermodynamically favored. The cis isomer would result from a non‐interrupted coordination of the catalyst to the arene during the hydrogenation. The formation of the trans isomer requires a π facial exchange, for example through a catalyst dissociation‐reassociation sequence from a chiral, dearomatized diene or olefin intermediate, prior to further hydrogenation. It can be argued that such a rearrangement is unlikely to occur, since the further hydrogenation of the dearomatized intermediates should be faster than the initial dearomative hydrogenation of the stabilized aromatic substrate. In addition, the catalyst would have to bind to the sterically more hindered π face following the facial exchange to then give the trans isomer. Nonetheless, the binding affinity of the metal catalyst to the particular species and π face, and ultimately the cis selectivity, is dependent on the reaction conditions as well as the electronic and steric properties of the substrate and those of the catalyst. In most cases, the trans isomer is indeed formed as a minor product. Recently, the Marks group disclosed a catalyst system that exclusively delivers the cis isomer.17 The group had previously reported on supported, single‐site18 organozirconium catalysts which consist of a cationic Cp*Zr(alkyl)2 (Cp*=C5Me5) precatalyst tethered to an anionic sulfated zirconiumoxide support.19 The different selectivities of the new Cp*Zr(benzyl)2 precatalyst (13) compared to the previous single‐site Cp*ZrMe2/ZrS precatalyst (12) were demonstrated with the hydrogenation of hexadeuterobenzene (9; Figure 2 A). Precatalyst 12 delivered a statistical 1:3 mixture of ααα‐(or all‐cis)‐hexadeuterocyclohexane (10) and αβα‐(or cis‐trans‐cis)‐hexadeuterocyclohexane (11). This result suggests that the sequential pairwise hydrogen transfer occurred randomly to both π faces.20 In contrast, the new precatalyst 13 delivered all‐cis‐isotopomer 10 exclusively. Careful mechanistic investigations revealed that the active species derived from 13 still included one benzoate substituent, whereas the active catalyst derived from 12 was completely hydrogenolyzed to the zirconium dihydride. Counterintuitively, the benzoate species derived from 13 had a lower binding affinity to the partially hydrogenated diene or olefin species, thus prompting the authors to conclude that the π facial exchange in the previous system should not involve the dissociation of intermediates from the metal center. Precatalyst 13 provides highly cis‐selective access to various alkylated cyclohexanes (14), which can be subsequently diversified to give more complex molecules. This is noteworthy, since the high electrophilicity of the catalyst prevents the use of substrates containing polar functional groups.

Figure 2.

A) Highly cis‐selective arene hydrogenation using a supported, single‐site organozirconium precatalyst (13). B) Relative stereochemistry of (−)‐menthol ((−)‐3) and its most stable conformation. Eq: equatorial orientation.

In some cases, the trans isomers of the multisubstituted saturated carbo‐ and heterocyclic products can be accessed from their cis analogues through nucleophilic substitution reactions; however, a trans‐selective hydrogenation would be both more general and direct. Notably, the hydrogenation of para‐xylene using a pyridine(diamine) molybdenum catalyst reported by the Chirik group delivers the product with a 1:1 d.r.21 Moreover, the Symrise methanol process includes a rare example of an arene hydrogenation that gives the racemic trans product as the major isomer.22 The hydrogenation is conducted at high temperatures and the observed product selectivities reflect the thermodynamic equilibria of the diastereomers. Each substituent of menthol lies in an equatorial orientation, thus making it the lowest energy isomer (Figure 2 B).23 Furthermore, the unwanted diastereo‐ and enantiomers can be recycled to give a >90 % overall yield for (−)‐menthol.3 To the best of our knowledge, however, no general procedures for trans‐selective arene hydrogenation are known.

2.2. Enantioselective Arene Hydrogenation

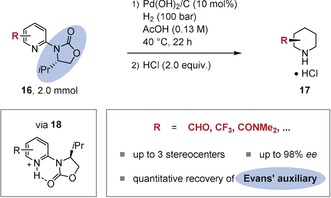

The enantioselective hydrogenation of arenes has been extensively explored following the first highly enantioselective (≥90 % ee) example reported in 1998.24 These efforts have been detailed comprehensively in a number of recent reviews.15g–15j Multiple strategies have been developed to affect chiral induction. Chiral auxiliaries may be attached to the substrate, thus facilitating a diastereoselective hydrogenation and hence enantioselective access to the chiral, saturated product upon removal of the chiral auxiliary. For example, the Glorius group developed a diastereoselective hydrogenation of pyridines using the Evans auxiliary (Figure 3).25 The reaction employs an achiral heterogeneous catalyst such as Pd(OH)2/C in acetic acid. The acidic medium is believed to play three important roles in the reaction. Firstly, hydride attack is facilitated by formation of a pyridinium ion. Secondly, catalyst poisoning by the Lewis basic substrate (16) or product is minimized by protonation. Thirdly, protonation locks the conformation of the chiral auxiliary, thus sterically blocking catalyst association on one face (18). The method allows the construction of up to three stereocenters. The chiral auxiliary may be cleaved in situ and recovered quantitatively. This means of enantioselective access to chiral piperidines in a single operation has been applied in organic synthesis.25b Although other methods that employ chiral auxiliaries for the enantioselective hydrogenation of benzoic or furanoic acid derivatives exist,26 the formation of a rigid conformation that effectively shields one face is nontrivial. The introduction and removal of the stoichiometric chiral auxiliary must be facile, which presents difficulties if it cannot be readily synthesized from the chiral pool and/or recovered, thereby limiting the scope of this underlying strategy.

Figure 3.

Enantioselective synthesis of piperidines by the diastereoselective hydrogenation of pyridines using the Evans auxiliary.

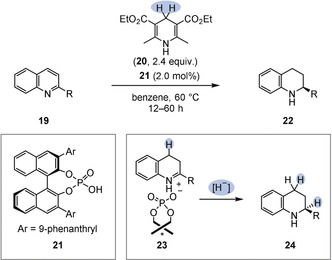

An elegant strategy that addresses this problem was advanced by Rueping et al. and later others.27 They discovered that a catalytic chiral phosphoric acid additive (e.g. 21) can be employed to activate basic N‐heteroarenes such as 2‐substituted quinolines (19) and the imine intermediates in the enantioselectivity‐determining step for hydride transfer (23; Figure 4). Either a Hantzsch ester (20) or molecular hydrogen in combination with an achiral transition‐metal catalyst may act as a hydride source. Although limited to basic N‐heteroarene substrates, this strategy is synthetically useful: in particular, the transfer hydrogenation showed a good tolerance of functional groups and is readily applicable on a laboratory scale.

Figure 4.

Enantioselective transfer hydrogenation of 2‐substituted quinolines (19) using a chiral Brønsted acid catalyst (21).

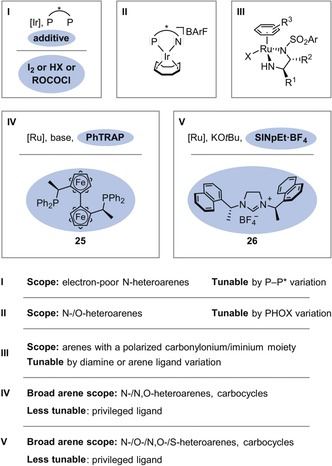

The use of homogeneous metal complexes with chiral ligands is, in principle, the most general strategy, and several privileged catalyst systems have emerged (Figure 5). The combination of iridium with chiral bisphosphine ligands (catalyst system I) has been studied intensively following its introduction by the group of Y.‐G. Zhou.6 In most cases, the catalyst system is used in combination with an additive. For example, iodine promotes hydrogenation by oxidation of the iridium(I) precatalyst to the active iridium(III) species.28 Chloroformates29 or Brønsted acids30 bind to the basic nitrogen atom of the heteroarene, thereby activating it for the dearomative hydride attack and preventing catalyst poisoning by the Lewis‐basic substrates or products. Halide‐bridged iridium(III) dimers, which have been studied by the Mashima group,31 represent an alternative precatalyst with a similar active species.31c The scope of catalyst system I includes a wide variety of electron‐poor N‐heteroarenes, and the catalyst system can be tuned to match a particular substrate by exploiting the facile accessibility of chiral bisphosphines. In addition to chiral bisphosphines, chiral P,N ligands such as phosphine‐oxazolines (PHOX) have been employed in combination with iridium (II) by the Charette28d and Pfaltz groups.32 In contrast to the (more nucleophilic) active iridium(III)‐monohydride species28e of precatalyst I, the active species of the iridium‐PHOX catalyst system (II) is an acidic iridium(III)‐dihydride complex,33 which is applicable to electron‐poor and electron‐rich N‐heteroarenes as well as O‐heteroarenes. Chiral ruthenium complexes can also catalyze the enantioselective hydrogenation of (hetero‐)arenes. For example, analogues of Noyori's transfer hydrogenation catalyst (III) have been employed by the groups of Q.‐H. Fan and A. S. C. Chan, as well as others, for the hydrogenation of arenes bearing polarized carbonylonium or iminium moieties.34 In addition, the Kuwano group has advanced the use of combinations of the privileged trans‐chelating chiral 2,2′′‐bis[1‐(diphenylphosphino)ethyl]‐1,1′′biferrocene (PhTRAP) ligand (25) with a ruthenium precursor under basic conditions (IV).35 The catalyst system is applicable to a broad range of divergent arene and heteroarene motifs.36 Of particular note is the ability of the catalyst to effect hydrogenation of strongly aromatic naphthalene.36d In terms of its divergent scope of applicable (hetero‐)arenes, this catalyst system is, arguably, surpassed only by the ruthenium bis(N‐heterocyclic carbene) (NHC) catalyst system (V)37 developed by the Glorius group, which was originally inspired by Chaudret's complex.38 This catalyst system can be prepared by deprotonation of the chiral NHC precursor (26)37g in the presence of a ruthenium source. Notably, this system can even catalyze the hydrogenation of thiophenes and benzothiophenes, which lead to strongly coordinating saturated products.37c Other catalyst systems based on rhodium or palladium39 have yet to demonstrate the general applicability of those discussed above.

Figure 5.

Established transition‐metal‐based catalyst systems for the enantioselective hydrogenation of (hetero‐)arenes and some relevant characteristics.

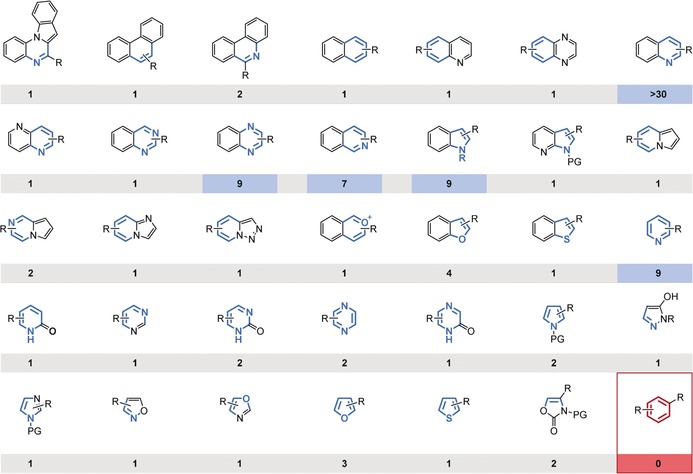

Together, these chiral transition‐metal‐based catalyst systems facilitate the highly enantioselective hydrogenation of a variety of heteroaromatic scaffolds (Figure 6). A summary of catalysts and conditions for each product motif can be found in the appendices of the recent reviews by the group of Y.‐G. Zhou.15g, 15j Each method, however, remains limited in terms of functional‐group tolerance and the substrate substitution pattern, particularly of the reactive aromatic ring. A certain substrate may require reoptimization of the reaction conditions, possibly benefiting from the tunability offered by catalyst systems I–III. Furthermore, there is a notable difference in the number of synthetic studies dedicated to the respective arene substrates. The hydrogenations of quinolines and, to a lesser extent, those of quinoxalines, isoquinolines, indoles, and pyridines are particularly well‐explored. Possible reasons include their more facile hydrogenation or a greater demand for the chiral product motif. In either case, well‐explored motifs might be comparatively more easily incorporated within a synthesis. Benzene derivatives, the archetypical arenes, present an obvious gap in the scope of all the current catalyst systems. This can be attributed to the high resonance energy (36 kcal mol−1) of benzene. For comparison, only 25 kcal mol−1 of resonance energy is lost during the (semi‐)hydrogenation of naphthalene.40 This difference in resonance energy would likely be reflected in the energies of the respective transition states. As a result, very few catalysts are able to surmount the activation barrier associated with the hydrogenation of benzene.41a In particular, homogeneous catalysts are generally unsuitable for the hydrogenation of benzene derivatives. A significant number of homogeneous precatalysts for the hydrogenation of benzene are known, but they have been shown to form heterogeneous active catalysts in situ. This vexing problem has been covered in excellent reviews by Widegren and Finke and, independently, by Dyson.41 Although enantioselective, heterogeneous catalyst systems are known,42 the development of such systems requires different, less established strategies compared to their homogeneous counterparts.

Figure 6.

Overview of the substrate scope of (highly) enantioselective arene hydrogenations catalyzed by chiral transition‐metal catalysts and the respective number of published synthetic methods (≥90 % ee, minimum two substrates).

3. Chemoselective Arene Hydrogenation

For the purpose of this Review, we define three major chemoselectivity challenges in the area of arene hydrogenation:

Other reducible sites present in functionalized arenes are usually hydrogenated in preference;

Multicyclic arenes incorporate several potentially reactive aromatic rings;

Hydrodefunctionalizations can occur for arenes bearing substituents with functional groups that are directly attached to the reactive aromatic ring.

These challenges are in addition to those pertaining to aromatic stability, steric hindrance at the ring, and poisoning effects. However, research into such challenges, exemplified by the (enantioselective) hydrogenation of the strongly aromatic naphthalenes,36d the highly coordinating thiophenes,37c or of triphenylphosphine,43 represent interesting subtopics in themselves. Herein, methods that provide solutions for the outlined chemoselectivity challenges are discussed, with a focus on those dealing with the most challenging, strongly aromatic benzene and pyridine derivatives, since we assume that the control of the chemoselectivity should be most difficult with these substrates. Furthermore, we would consider that methods using commercially available or readily prepared catalyst systems can be expected to find more immediate application in organic synthesis and are discussed preferentially.

3.1. Preferential Hydrogenation of Arenes in the Presence of Easily Reducible Moieties

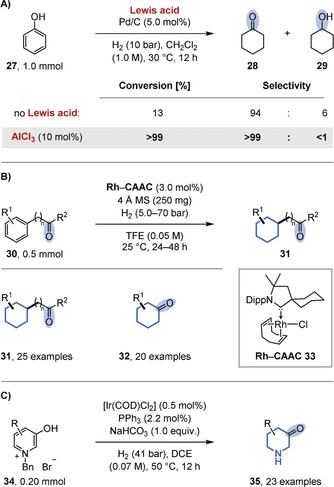

Carbonyl groups are a common reducible unit in organic chemistry. Whereas carboxylic acid derivatives are generally well‐tolerated, ketones and aldehydes are normally hydrogenated preferentially over arenes. The chemoselective hydrogenation of arenes in the presence of these functional groups has been the focus of a number of studies.44

For example, the chemoselective hydrogenation of phenol (27) to cyclohexanone (28) was targeted because of the huge commercial demand for the product. Since cyclohexanone is an intermediate in the total hydrogenation of phenol to cyclohexanol (29), several reports disclose selectivity towards cyclohexanone at low conversion. A remarkably simple solution was discovered by the groups of Jiang and Han.44c Through the use of a catalyst system consisting of (commercial) heterogeneous palladium catalysts (e.g. Pd/C or Pd/Al2O3) and Lewis acids (e.g. AlCl3 or ZnCl2), quantitative conversions are combined with essentially 100 % selectivity for cyclohexanone (Figure 7 A). The authors assume that the Lewis acid activates the phenol for hydrogenation but reduces the rate of the further hydrogenation of cyclohexanone by coordination. Since catalytic amounts of the Lewis acid are sufficient, the interaction of the palladium catalyst with the Lewis acid may offer an alternative mechanistic rationale. In 2015 the Zeng group disclosed a general and selective method for the preferential hydrogenation of arenes in the presence of ketones (Figure 7 B).44f The authors discovered that the use of rhodium precatalysts containing strongly electron‐donating cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbenes (CAACs; e.g. 33) were key to achieving high selectivities. These ligands, as well as their rhodium complexes, had previously been introduced by the Bertrand group as part of their impressive research program on strongly electron‐donating carbenes.45 Other rhodium complexes, including those derived from related classical, less electron‐donating imidazolium‐derived NHCs, provided either low conversions or low selectivities. The authors assumed that the highly electron‐rich metal center, as a result of the CAAC ligands, would favor arene binding through back‐donation into the antibonding π orbitals of the arene. Although slight variations of the conditions were required to ensure preservation of the ketone functionality for all the substrates, the broad applicability of the catalyst system is impressive, since it includes multiple additional functional groups attached to the (hetero‐)arene substrates. With a slight variation of the conditions, the system is also applicable to the semihydrogenation of phenols. On the basis of a mercury drop test, the authors initially assumed the active catalyst to be homogeneous in nature. A recent mechanistic study by the Bullock group, however, which included kinetic studies, quantitative poisoning experiments,46 and analytical techniques (Rh K‐edge XAFS, STEM, IR), indicated that rhodium nanoparticles are the active species.47 Finally, the group of Y.‐G. Zhou disclosed a method dedicated to the synthesis of 3‐piperidones (35) starting from activated, benzyl‐protected hydroxypyridinium salts (34; Figure 7 C).44g The scope includes unsubstituted, 2‐/4‐alkyl‐ and 2‐/4‐aryl‐substituted substrates, while tolerating various remote functional groups. The disclosed semihydrogenation of such 3‐hydroxypyridines is more difficult than that of 2‐hydroxypyridines, which form stable amides upon hydrogenation. Consequently, a variety of cyclohexanones and other saturated carbo‐ and heterocycles containing ketones can be prepared by hydrogenation, often obviating the need for protecting groups or subsequent reoxidations.

Figure 7.

Chemoselective hydrogenation of arenes in the presence of ketones. A) Effect of a Lewis acid on the partial hydrogenation of phenol (27). B) Chemoselective hydrogenation of aromatic ketones (30) using rhodium‐CAAC complexes (e.g. 33). C) Chemoselective partial hydrogenation of 3‐hydroxypyridinium salts (34). COD=1,5‐cyclooctadiene, DCE=1,2‐dichloroethane, TFE=2,2,2‐trifluoroethanol.

Strategically, the chemoselective hydrogenation of arenes in the presence of alkenes is even more relevant, since comparatively broadly applicable protection or reoxidation reactions are not known. Foremost, an industrial process for the semihydrogenation of benzene to cyclohexene has been developed by Asahi Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.2 The product is an important intermediate in the production of cyclohexanone for the manufacture of nylon. The process uses zinc‐based Lewis acid additives, which are believed to stabilize the alkene through coordination, and an innovative, four‐phase reactor consisting of a solid catalyst layer surrounded by an aqueous layer, the organic phase, and gas‐phase H2. This setup is believed to favor partial hydrogenation owing to the higher solubility of benzene relative to cyclohexene in the aqueous layer.48 The partial hydrogenation of benzene to cyclohexadiene is even more challenging, since the reaction is endergonic. As a result, cyclohexadienes have so far only been synthesized in small quantities by hydrogenation, whereas cyclohexene can be produced in 60 % yield on an industrial scale.49 The chemoselective hydrogenation of phenyl rings in the presence of acyclic alkenes has been observed, but no general method is known.50

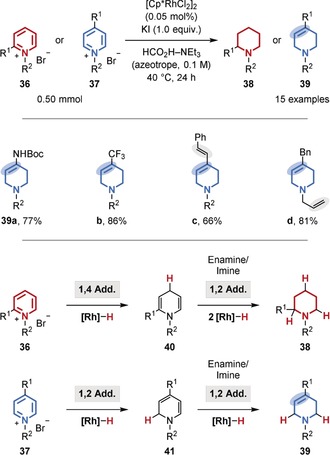

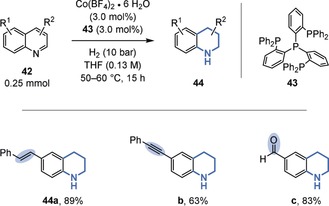

The chemoselective hydrogenation of heteroarenes in the presence of alkenes is, however, more common, likely owing to the reduced aromaticity and inherent bond polarization.51 For example, a general method for the chemoselective, semihydrogenation of 4‐substituted pyridinium salts (37)52 was disclosed by the Xiao group (Figure 8).51b The transformation uses an azeotropic mixture of formic acid and triethylamine as the hydrogen source, a commercial rhodium catalyst in low loading (turnover number (TON) up to 9000), and potassium iodide as an additive. Whereas 2‐substituted pyridinium salts (36) gave predominantly perhydrogenated piperidines (38), 4‐substituted pyridinium salts (37) provided the semihydrogenated, 3,4‐unsaturated tetrahydropiperidines (39) almost exclusively. The authors explained this surprising result by steric blocking of the 1,4‐hydride addition in the case of the 4‐substituted substrates (37). As a result, one double bond remains that cannot isomerize to a polarized iminium species (39). The tolerance of the catalyst system for unpolarized double bonds is further highlighted by the preservation of the acyclic double bonds in 39 c,d. Moreover, a chemoselective hydrogenation of quinolines catalyzed by an inexpensive cobalt catalyst was disclosed by the Beller group (Figure 9). In addition to an alkene within a stilbene motif (44 a), even an alkyne within a tolane motif (44 b) as well as an aldehyde (44 c) were well‐tolerated.51d

Figure 8.

Chemoselective transfer hydrogenation of pyridinium salts.

Figure 9.

Chemoselective hydrogenation of quinolines in the presence of an alkene, an alkyne, and an aldehyde.

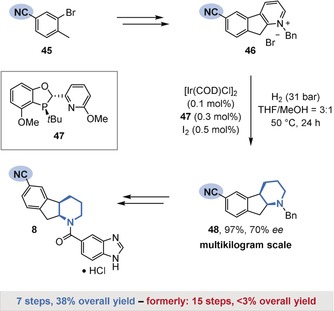

The preservation of nitriles during the hydrogenation of heteroarenes is known.53 For example, a recent synthesis of a promising Type 2 diabetes inhibitor (8) by a team from Boehringer Ingelheim and the University of Pennsylvania involved the chemoselective hydrogenation of indenopyridinium salt 46 in the presence of a nitrile group as a key step (Figure 10).10a Although heterogeneous catalysts proved inadequate owing to competing side reactions such as nitrile reduction, an extensive screening of homogeneous catalyst systems revealed a combination of iridium and a dihydrobenzooxaphosphole ligand 47 to be well‐suited for the desired transformation. The product 48 was formed in an excellent yield on a multikilogram scale, with complete preservation of the nitrile group and with good enantioselectivity. 48 was efficiently converted into the desired product (8) by deprotection, kinetic resolution, and subsequent amide coupling. In total, the therapeutic agent 8 was obtained in excellent overall yield (38 %) in a concise seven‐step sequence. The chemoselective arene hydrogenation offers a significant synthetic shortcut compared to the previous route (15 steps, less than 3 % overall yield).

Figure 10.

Boehringer Ingelheim's synthesis of a potent therapeutic agent (8) against Type 2 diabetes by the chemoselective hydrogenation of pyridinium salt 46.

In comparison to the chemoselective hydrogenation of arenes bearing ketones, alkenes, or nitriles, the chemoselective hydrogenation of arenes bearing other unsaturated moieties such as nitro groups, imines, azides, sulfoxides, or others is less explored. Nevertheless, it cannot necessarily be concluded that their presence causes a greater challenge in terms of chemoselectivity.54

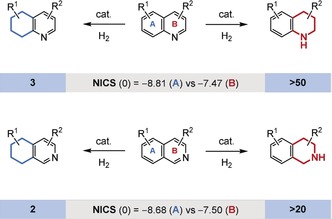

3.2. Regioselective Hydrogenation of Aromatic Substrates Bearing Multiple Aromatic Moieties

In substrates bearing multiple aromatic moieties, the ring with the lowest resonance energy is generally hydrogenated in preference. For example, it is well‐documented that the hydrogenation of quinolines, isoquinolines, and their analogues occurs at the least aromatic, heteroaromatic ring (Figure 11).55 A general rationale for the strength of the aromatic stabilization energy of a particular ring can often be obtained from the easily calculated nucleus‐independent chemical shift (NICS) values.56 The NICS value identifies the hypothetical chemical shift inside the aromatic ring. As a result of the ring current, the values are strongly negative. Consequently, aromatic rings with a more negative NICS value can be expected to show a stronger aromatic character. It is tempting to rely purely on such values for the estimation of the reactivity of an aromatic ring during hydrogenation, but the NICS value, like other parameters that estimate aromaticity, can produce some curious results.57 Moreover, regioselectivity in the hydrogenation of fused aromatic rings is dependent on the electronic and steric properties of the substrate. For example, the regioselectivity of the hydrogenation of free indole derivatives can switch from the less aromatic N‐containing ring to the carbocyclic rings when electron‐withdrawing substituents are present on the N‐containing ring.58 Such groups destabilize the formation of the reactive iminium salt intermediates. Furthermore, installation of the Evans bulky chiral oxazolidone in quinolines facilitates the regioselective reduction of the carbocyclic ring.25c

Figure 11.

Regioselective hydrogenation of quinolines and isoquinolines and the respective number of published synthetic methods (≥50 % yield, at least two substrates). The NICS(0) value refers to the center of the ring.

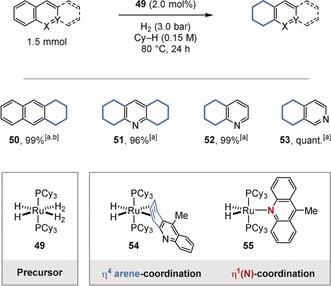

In contrast, a catalyst‐controlled, regioselective hydrogenation of the more aromatic ring, which is not purely governed by substrate electronic or steric effects, is a desirable goal. For example, the groups of Borowski and Sabo‐Etienne showed that a series of anthracene and acridine derivatives were regioselectively hydrogenated at their external carbocyclic rings using Chaudret's electron‐rich ruthenium complex (50–53; Figure 12).38 The authors rationalized this observation with the preferential η4‐arene coordination (54), which is accompanied by a loss of aromaticity compared to the η1(N) mode (55). Complex 54 could be characterized by NMR spectroscopy.

Figure 12.

Regioselective hydrogenation of polycyclic aromatic compounds using Chaudret's complex (49). It was suggested that a preferential Ru‐η4‐arene coordination determines the regioselectivity. [a] GC yields. [b] 1 h reaction time. Cy=cyclohexyl.

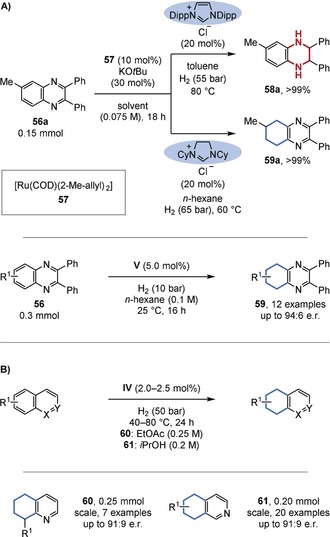

Inspired by the reactivity of Chaudret's complex (49), the Glorius group developed a related, NHC‐based catalyst system (Figure 13 A).37a Interestingly, the regioselectivity was strongly dependent on the NHC ligand. Further ligand variation culminated in the development of chiral catalyst system V for the homogeneous enantioselective hydrogenation of (hetero‐)arenes. The chiral ruthenium‐PhTRAP catalyst system developed by the Kuwano group (IV) also showed a preference for the carbocyclic ring over the less aromatic N‐containing ring in quinolines and isoquinolines (Figure 13 B).36e, 36g A large bite angle of the employed bisphosphine was key to achieving chemoselective hydrogenation.

Figure 13.

A) Regio‐ and enantioselective hydrogenation of quinoxalines. B) Regio‐ and enantioselective hydrogenation of quinolines and isoquinolines. Dipp=2,6‐diisopropylphenyl.

The chemoselective hydrogenation of naphthols has been investigated because of the synthetic interest in the regioisomers of tetrahydronaphthols, which are common motifs in secondary metabolites. A chemoselective hydrogenation of the phenol ring was achieved by the Huang group using ruthenium pincer complex 64.59a Since no reaction occurred in the absence of a hydroxy group, the authors proposed that the hydrogenation proceeds via a non‐aromatic ketone tautomer (67; Figure 14 A). The opposite regioselectivity, as achieved by the Zeng group, can be achieved with a heterogeneous catalyst that is prepared in situ from [Rh(COD)Cl]2 and polymethylhydrogen siloxane (PMHS) as the hydrogen source.59b It is possible that the hydrosilane also acts to protect the alcohol, thus forming a stable silyl‐enol species that prevent the formation of activated ketone tautomers. This may drive the reaction to the sterically more accessible benzene ring (Figure 14 B).

Figure 14.

A) Regioselective hydrogenation of naphthols (62, 63) to the 1,2,3,4‐tetrahydronaphthols (65, 66). B) Regioselective hydrogenation of naphthols to 5,6,7,8‐tetrahydronaphthols (68). TMS=trimethylsilyl.

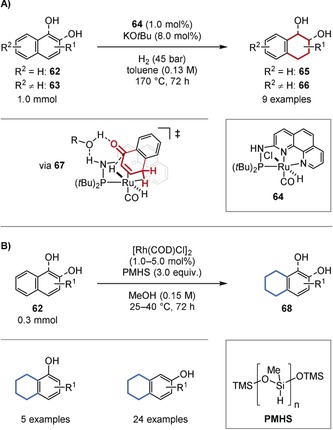

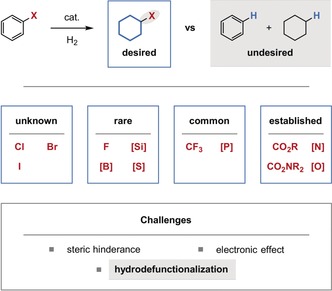

3.3. Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Arenes with Directly Attached Labile Functional Groups

During our extensive studies on arene hydrogenation we have identified the challenging hydrogenation of arenes bearing functional groups directly attached to the reactive aromatic ring as a limit to the synthetic utility of the transformation. Such functional groups could greatly increase the value of the products by altering the physical properties or by serving as a handle for the incorporation of the saturated motifs into more complex structures. In general terms, the functionalization of arenes is more facile than that of the saturated products.60 Naturally, the tolerance of functional groups is dependent on their chemical properties. Many groups such as carboxylic acids/esters, amines,61 amides, and alcohols/ethers are commonly tolerated (Figure 15). Other less frequently tolerated functional groups, when directly attached to the arene, may sterically hinder the productive coordination of the arene to the catalyst. Additionally, certain functional groups may negatively influence the electronic properties of the arene at the reaction center. Finally, new mechanistic pathways for hydrodefunctionalization may become feasible because of the proximity of the functional group to the catalyst during arene hydrogenation, or as a result of the formation of dearomatized intermediates in which the functional group is activated for hydrodefunctionalization. For example, dearomatization may render the functional group in a newly allylic position.

Figure 15.

Tolerance of functional groups directly attached to the reactive arene. The stated frequencies of tolerance are based on our knowledge of the available literature for the hydrogenation of benzene derivatives.62 [Si]: silyl group; [B]: boryl group; [S]: sulfur‐containing functional group including an S‐phenyl substituent; [P], [N], [O] are defined analogously.

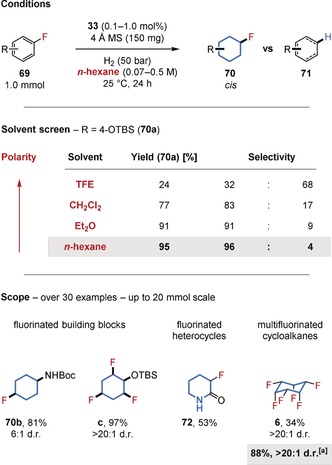

The application of fluorinated, saturated compounds has been widely explored in the fields of agrochemistry, pharmaceuticals, and materials science.63 Research by the O'Hagan group has demonstrated the potential of all‐cis‐multifluorinated cycloalkanes (e.g. 6) as highly polar building blocks.64 Inspired by O'Hagan's work, we became interested in developing a cis‐selective hydrogenation procedure that tolerates fluorine substituents directly attached to the reactive arene (Figure 16);8b however, the transformation of inexpensive (multi‐)fluorinated arenes (69) into such molecules needed to overcome the well‐known hydrodefluorination side reaction (to 71). Although the C−F bond is very strong, several mechanistic pathways are known to lead to a net hydrodefluorination.65 We observed, however, that the formation of the undesired products is decreased when the Bertrand–Zeng complex 33 is used as a precatalyst under mild conditions. Furthermore, the choice of solvent proved crucial, with nonpolar n‐hexane giving a highly selective hydrogenation.66 It is possible that less polar solvents decrease the rate of defluorination mechanisms proceeding via a polar intermediate. Likewise, the higher solubility of hydrogen gas in nonpolar solvents might affect the rate of the desired hydrogenation relative to the undesired hydrodefluorination.67 Furthermore, polar solvents may interact with, and alter the structure of, the active catalyst. The developed conditions provide convenient access to cis‐stereodefined (multi‐)fluorinated building blocks containing a second functional group for further derivatization (e.g. 70 a–c), saturated fluorinated heterocycles (e.g. 72) and polar all‐cis‐multifluorinated cycloalkanes (e.g. 6). Some of the reaction products are currently being made commercially available.68

Figure 16.

Chemoselective hydrogenation of fluorinated arenes. [a] New conditions using 450 mg SiO2 instead of 4 Å MS.

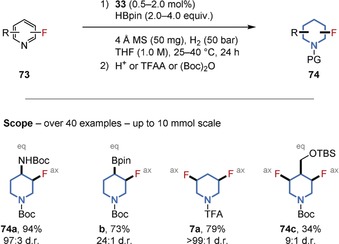

Despite the generality of the former strategy, fluorinated pyridine derivatives were not tolerated, presumably as a result of catalyst deactivation by the Lewis‐basic N‐heterocycles. We therefore developed an alternative method that provided diastereoselective access to a broad range of substituted, all‐cis‐(multi‐)fluorinated piperidines in a single operation. We believe the reaction occurs via a pyridine dearomatization by HBPin, followed by the total saturation of the boron‐protected, dearomatized intermediates (Figure 17).9b Versatile (multi‐)fluorinated building blocks and motifs containing further functional groups, such as fluorinated aminopiperidine 74 a, a common fragment in medicinal chemistry, were obtained and commercialized (e.g. 74 a–c and 7 a).68 The straightforward preparation of these motifs enabled determination of the axial/equatorial orientation of the substituents by NMR spectroscopy.69

Figure 17.

Chemoselective hydrogenation of fluorinated pyridines. Defined orientations of the substituents were determined. PG=protecting group (H, TFA, or Boc), TFAA=trifluoroacetic anhydride.

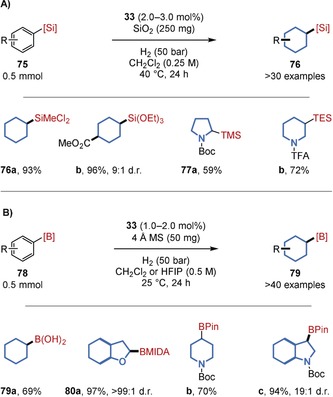

The successful hydrogenation of fluorinated arenes inspired us to develop procedures for the hydrogenation of arenes decorated with other synthetically useful functional groups attached to the reactive arene. Silyl groups are widely utilized within organic synthesis, materials science, pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and fragrance research;70 however, silylated saturated carbo‐ and heterocycles represent a synthetic challenge for many established transformations.71 Making use of the facile accessibility of silylated arenes (75), a general, cis‐selective procedure to access such products was provided by an arene hydrogenation catalyzed by rhodium‐CAAC 33 (Figure 18 A).72 Notably, the synthetically most useful alkoxy‐ and halosilyl substituents were well‐tolerated, thus generating the products (76 a,b) that can be used as building blocks in polymer chemistry or organic synthesis.73 During optimization, a significant enhancement of the yield was observed when using increased amounts of the silica gel additive. This positive effect was also applied to the previously low‐yielding hydrogenation of very highly fluorinated arenes and facilitated almost quantitative yields (6; Figure 16). Interestingly, no such effect was detected with the previously employed 4 Å molecular sieves (MS). A general synthetic study was likewise performed for the hydrogenation of borylated arenes (78; Figure 18 B).74a Under the optimal reaction conditions, boronic acids (79 a) as well as a wide range of boron protecting groups (80 a–c) were well‐tolerated. The further tolerance of several other functional groups allows access to (substituted) borylated carbo‐ and heterocycles, which were obtained with high cis selectivities. These products can readily be derivatized via the boryl group. A notable, closely related study was disclosed recently by the Zeng group.74b

Figure 18.

Chemoselective procedures for the hydrogenation of A) silylated and B) borylated arenes. HFIP=Hexafluoroisopropanol, MIDA=N‐Methyliminodiacetate.

4. Conclusions

Arene hydrogenation is an increasingly important strategic transformation for the direct preparation of saturated carbo‐ and heterocycles; such transformations are already applied on a multithousand ton scale in industry. The demand for such compounds in the fine‐chemicals sector has prompted further development of diastereo‐, enantio‐, and chemoselective methods for the hydrogenation of functionalized arenes.

A high level of (cis‐)diastereoselectivity is typically inherent to the transformation. Enantioselective methods make use of chiral auxiliaries, chiral phosphoric acids, or chiral transition‐metal catalysts. In particular, the use of chiral transition‐metal catalysts facilitates general access to valuable product motifs, such as piperidines. Moreover, complex, desirable structures can be generated using highly chemoselective methods. Such challenges have been solved for arenes bearing reducible functional groups, multicyclic arenes, and for arenes bearing directly attached, labile functional groups.

Although many interesting synthetic applications can be realized with current technologies, many challenges remain. Most importantly, from a synthetic chemistry perspective, the existing methods are often limited in scope, which makes their application to complex substrates difficult. In addition, we consider the development of methods that overcome the following unsolved challenges to be most relevant:

trans‐selective arene hydrogenation;

catalytic, enantioselective hydrogenation of simple benzene derivatives or phenols;

arene hydrogenation at low or even ambient pressure.

Research in each of these areas will benefit from further mechanistic understanding, which is often limited by the high hydrogen pressures required, and the innovation of new catalyst systems.

Given the inability of the vast majority of homogeneous catalysts to hydrogenate monocyclic benzene derivatives, the enantioselective hydrogenation of these substrates may eventually be realized under enantioselective, heterogeneous catalysis. Finally, the development of a user‐friendly, tunable homogeneous catalyst for the hydrogenation of monocyclic benzene derivatives, analogous to Wilkinson's catalyst for the hydrogenation of alkenes, would open up a means to rationally approach existing selectivity challenges and undoubtedly revolutionize the field.

Conflict of interest

M.P.W., Z.N., and F.G. are inventors on German patent applications 10 2017 106 467.2 and 10 2018 104 201.9, held and submitted by Westfälische Wilhelms‐Universität Münster. These patent applications cover methods for the synthesis of fluorinated cyclic aliphatic and heterocyclic compounds. See Figures 16 and 17.

Biographical Information

Mario Wiesenfeldt studied chemistry at the Ruprecht Karls‐Universität Heidelberg and obtained his MSc in 2015. His studies included exchanges at the University of York and the California Institute of Technology, where he conducted his MSc research with Prof. Brian M. Stoltz. He obtained his PhD in 2018 for studies on arene hydrogenation under the supervision of Prof. Frank Glorius at the Westfälische Wilhelms‐Universität Münster. He is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the group of Prof. David W. C. MacMillan at Princeton University.

Biographical Information

Zackaria Nairoukh obtained his PhD in organic chemistry under the supervision of Prof. Jochanan Blum at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2014. He then joined Prof. Ilan Marek's group at the Technion‐Israel Institute of Technology for postdoctoral research in the area of metal‐mediated stereoselective transformations. In 2017 he joined Prof. Frank Glorius's group at the Westfälische Wilhelms‐Universität Münster as a Minerva postdoctoral fellow, where he is currently researching chemoselective arene hydrogenation.

Biographical Information

Toryn Dalton read Natural Sciences at Trinity College, Cambridge, receiving his MSci in 2014. From there, he joined GSK as a process chemist at the Medicines Research Centre, Stevenage, where he also completed a secondment in the Flexible Discovery Unit. He is currently a first year doctoral student under the supervision of Prof. Frank Glorius at the WWU Münster and a member of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Biographical Information

Frank Glorius is a Full Professor of Organic Chemistry at the Westfälische Wilhelms‐Universität Münster. His research program focuses on the development of new concepts for catalysis in areas such as C−H activation, smart screening and data analysis, photocatalysis, and N‐heterocyclic carbenes in organocatalysis, as surface modifiers, and in (asymmetric) arene hydrogenation.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes (M.P.W.), the Hans‐Jensen‐Minerva Foundation (Z.N.), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Leibniz Award, SFB 858 (T.D.)), and the European Research Council (ERC Advanced Grant Agreement no. 788558) for generous financial support. Furthermore, we are grateful to Prof. A. Pfaltz and Prof. Y.‐G. Zhou for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

M. P. Wiesenfeldt, Z. Nairoukh, T. Dalton, F. Glorius, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10460.

Dedicated to Professor Ryōji Noyori on the occasion of his 80th birthday

References

- 1. Weissermel K., Arpe H.-J., Industrial organic chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2008, pp. 337–385. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Nagahara H., Ono M., Konishi M., Fukuoka Y., Appl. Surf. Sci. 1997, 121–122, 448; [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Foppa L., Dupont J., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Review:

- 3a. Sell C. S. in The Chemistry of fragrances. From perfumer to consumer, Vol. 38 (Ed.: C. S. Sell), Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, 2006, pp. 52–131; patent: [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Biedermann W. (BAYER AG), DE2314813, 1974; isomerization process:

- 3c. Etzold B., Jess A., Nobis M., Catal. Today 2009, 140, 30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Recent review: Chen S., Wojcieszak R., Dumeignil F., Marceau E., Royer S., Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 11023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Preuster P., Papp C., Wasserscheid P., Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang W.-B., Lu S.-M., Yang P.-Y., Han X.-W., Zhou Y.-G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Welin E. R. et al., Science 2019, 363, 270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Previous synthesis:

- 8a. Keddie N. S., Slawin A. M. Z., Lebl T., Philp D., O'Hagan D., Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 483; direct synthesis by arene hydrogenation: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Wiesenfeldt M. P., Nairoukh Z., Li W., Glorius F., Science 2017, 357, 908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Previous synthesis:

- 9a. Snyder J. P., Chandrakumar N. S., Sato H., Lankin D. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 544; direct synthesis by arene hydrogenation: [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Nairoukh Z., Wollenburg M., Bergander K., Glorius F., Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Synthesis:

- 10a. Wei X. et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15473; development of the enantioselective hydrogenation methodology: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Qu B. et al., Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 4920; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Qu B. et al., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Even enantioselective versions are well-established. Selected recent reviews on the enantioselective hydrogenation of alkenes:

- 11a. Ager D. J. in The handbook of homogeneous hydrogenation (Eds.: J. G. de Vries, C. J. Elsevier), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2006, pp. 744–772; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Roseblade S. J., Pfaltz A., Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 1402; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Woodmansee D. H., Pfaltz A., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 7912; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11d. Verendel J. J., Pàmies O., Diéguez M., Andersson P. G., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2130; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11e. Chirik P. J., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1687; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11f. Margarita C., Andersson P. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selected recent reviews on the enantioselective hydrogenation of ketones:

- 12a. Noyori R., Ohkuma T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 40; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2001, 113, 40; [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Li Y.-Y., Yu S.-L., Shen W.-Y., Gao J.-X., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A review on the enantioselective hydrogenation of imines/enamines: Xie J.-H., Zhu S.-F., Zhou Q.-L., Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sabatier P., Senderens J.-B., C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 1901, 132, 210. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overviews on catalyst systems for arene hydrogenation:

- 15a. Bianchini C., Meli A., Vizza F. in The handbook of homogeneous hydrogenation (Eds.: J. G. de Vries, C. J. Elsevier), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2006, pp. 455–488; [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Foubelo F., Yus M. in Arene chemistry. Reaction mechanisms and methods for aromatic compounds (Ed.: J. Mortier), Wiley, Hoboken, 2016, pp. 337–364; nanoparticle-catalyzed arene hydrogenation: [Google Scholar]

- 15c. Gual A., Godard C., Castillón S., Claver C., Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 11499; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15d. Qi S.-C., Wei X.-Y., Zong Z.-M., Wang Y.-K., RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 14219; homogeneous arene hydrogenation: [Google Scholar]

- 15e. Giustra Z. X., Ishibashi J. S. A., Liu S.-Y., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 314, 134; diastereoselective arene hydrogenation: [Google Scholar]

- 15f. Gualandi A., Savoia D., RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 18419; enantioselective arene hydrogenation: [Google Scholar]

- 15g. Wang D.-S., Chen Q.-A., Lu S.-M., Zhou Y.-G., Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2557; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15h. He Y.-M., Song F.-T., Fan Q.-H., Top. Curr. Chem. 2013, 343, 145; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15i. Zhao D., Candish L., Paul D., Glorius F., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5978; [Google Scholar]

- 15j. Shi L., Zhou Y.-G., Org. React. 2018, 95, 10.1002/0471264180.or096.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wertjes W. C., Southgate E. H., Sarlah D., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stalzer M. M., Nicholas C. P., Bhattacharyya A., Motta A., Delferro M., Marks T. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5263; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 5349. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The active catalyst appears to be homogeneous according to Schwartz's definition, since all the catalytically active sites are identical, see: Schwartz J., Acc. Chem. Res. 1985, 18, 302. [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Ahn H., Nicholas C. P., Marks T. J., Organometallics 2002, 21, 1788; [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Williams L. A., Guo N., Motta A., Delferro M., Fragalà I. L., Miller J. T., Marks T. J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 413; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19c. Gu W. et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The intermediates of the hydrogenation of C6D6 (9) have sterically identical faces. As a result, the cis/trans ratio is not influenced by steric factors.

- 21. Joannou M. V., Bezdek M. J., Chirik P. J., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5276. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Product distribution: rac-menthol/rac-neomenthol/rac-isomenthol=60:30:10. Only trace amounts of neoisomenthol is formed. See: Ref. [3].

- 23. Härtner J., Reinscheid U. M., J. Mol. Struct. 2008, 872, 125. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bianchini C., Barbaro P., Scapacci G., Farnetti E., Graziani M., Organometallics 1998, 17, 3308. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Method for the diasteroselective hydrogenation of pyridines:

- 25a. Glorius F., Spielkamp N., Holle S., Goddard R., Lehmann C. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 2850; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 2910; application of that method in organic synthesis: [Google Scholar]

- 25b. Scheiper B., Glorius F., Leitner A., Fürstner A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 11960; related diastereoselective hydrogenation of quinolines: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25c. Heitbaum M., Fröhlich R., Glorius F., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 357. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selected references on benzene derivatives:

- 26a. Besson M., Neto S., Pinel C., Chem. Commun. 1998, 1431; [Google Scholar]

- 26b. Besson M., Delbecq F., Gallezot P., Neto S., Pinel C., Chem. Eur. J. 2000, 6, 949; furan derivatives: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26c. Sebek M., Holz J., Börner A., Jähnisch K., Synlett 2009, 461. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selected references:

- 27a. Rueping M., Antonchick A. P., Theissmann T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3683; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 3765; [Google Scholar]

- 27b. Rueping M., Antonchick A. P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4562; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 4646; [Google Scholar]

- 27c. Rueping M., Theissmann T., Raja S., Bats J. W., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008, 350, 1001; [Google Scholar]

- 27d. Guo Q.-S., Du D.-M., Xu J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 759; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 771; [Google Scholar]

- 27e. Rueping M., Tato F., Schoepke F. R., Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 2688; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27f. Chen Q.-A., Wang D.-S., Zhou Y.-G., Duan Y., Fan H.-J., Yang Y., Zhang Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6126; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27g. Chen Q.-A., Gao K., Duan Y., Ye Z.-S., Shi L., Yang Y., Zhou Y.-G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2442; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27h. Fleischer S., Zhou S., Werkmeister S., Junge K., Beller M., Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 4997; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27i. Cai X.-F., Guo R.-N., Feng G.-S., Wu B., Zhou Y.-G., Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.First example:

- 28a.Ref. [6]; selected other references on the use of I2 in the iridium-bisphosphine-catalyzed hydrogenation:

- 28b. Xiao D., Zhang X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3425; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2001, 113, 3533; [Google Scholar]

- 28c. Dorta R., Broggini D., Stoop R., Rüegger H., Spindler F., Togni A., Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10, 267; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28d. Legault C. Y., Charette A. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 8966; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28e. Wang D.-W., Wang X.-B., Wang D.-S., Lu S.-M., Zhou Y.-G., Li Y.-X., J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Initial study on the use of chloroformates in arene hydrogenation: Lu S.-M., Wang Y.-Q., Han X.-W., Zhou Y.-G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 2260; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 2318. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selected references on the use of Brønsted acid additives in arene hydrogenation:

- 30a. Li Z.-W., Wang T.-L., He Y.-M., Wang Z.-J., Fan Q.-H., Pan J., Xu L.-J., Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 5265; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30b. Mršić N., Lefort L., Boogers J. A. F., Minnaard A. J., Feringa B. L., de Vries J. G., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008, 350, 1081; [Google Scholar]

- 30c. Zhou H., Li Z., Wang Z., Wang T., Xu L., He Y., Fan Q.-H., Pan J., Gu L., Chan A. S. C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8464; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 8592; iridium-bisphosphine-catalyzed arene hydrogenation: [Google Scholar]

- 30d. Tadaoka H., Cartigny D., Nagano T., Gosavi T., Ayad T., Genêt J.-P., Ohshima T., Ratovelomanana-Vidal V., Mashima K., Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 9990; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30e. Wang D.-S., Zhou Y.-G., Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 3014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selected references:

- 31a. Yamagata T., Tadaoka H., Nagata M., Hirao T., Kataoka Y., Ratovelomanana-Vidal V., Genet J. P., Mashima K., Organometallics 2006, 25, 2505; [Google Scholar]

- 31b. Iimuro A., Yamaji K., Kandula S., Nagano T., Kita Y., Mashima K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2046; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 2100; [Google Scholar]

- 31c. Kita Y., Yamaji K., Higashida K., Sathaiah K., Iimuro A., Mashima K., Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.

- 32a. Kaiser S., Smidt S. P., Pfaltz A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 5194; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 5318; [Google Scholar]

- 32b. Pauli L., Tannert R., Scheil R., Pfaltz A., Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gruber S., Pfaltz A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1896; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 34.N-Heteroarenes are only hydrogenated under acidic conditions. Selected references:

- 34a. Wang T., Zhuo L.-G., Li Z., Chen F., Ding Z., He Y., Fan Q.-H., Xiang J., Yu Z.-X., Chan A. S. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9878; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34b. Touge T., Arai T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 11299; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34c. Miao T., Tian Z.-Y., He Y.-M., Chen F., Chen Y., Yu Z.-X., Fan Q.-H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4135; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 4199. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sawamura M., Hamashima H., Sugawara M., Kuwano R., Ito Y., Organometallics 1995, 14, 4549. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selected references:

- 36a. Kuwano R., Kashiwabara M., Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 2653; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36b. Kuwano R., Kashiwabara M., Ohsumi M., Kusano H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 808; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36c. Kuwano R., Kameyama N., Ikeda R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7312; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36d. Kuwano R., Morioka R., Kashiwabara M., Kameyama N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4136; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 4212; [Google Scholar]

- 36e. Kuwano R., Ikeda R., Hirasada K., Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 7558; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36f. Makida Y., Saita M., Kuramoto T., Ishizuka K., Kuwano R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11859; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 12038; [Google Scholar]

- 36g. Jin Y., Makida Y., Uchida T., Kuwano R., J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selected references:

- 37a. Urban S., Ortega N., Glorius F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3803; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 3887; [Google Scholar]

- 37b. Ortega N., Urban S., Beiring B., Glorius F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1710; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 1742; [Google Scholar]

- 37c. Urban S., Beiring B., Ortega N., Paul D., Glorius F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15241; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37d. Ortega N., Tang D.-T. D., Urban S., Zhao D., Glorius F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9500; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 9678; [Google Scholar]

- 37e. Wysocki J., Ortega N., Glorius F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8751; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 8896; [Google Scholar]

- 37f. Schlepphorst C., Wiesenfeldt M. P., Glorius F., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 356; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37g.the protonated precursor of the chiral N-heterocyclic carbene is being commercialized by Merck Millipore. Product number: 905542.

- 38.Complex synthesis:

- 38a. Chaudret B., Poilblanc R., Organometallics 1985, 4, 1722; application in arene hydrogenation: [Google Scholar]

- 38b. Borowski A. F., Sabo-Etienne S., Donnadieu B., Chaudret B., Organometallics 2003, 22, 1630; [Google Scholar]

- 38c. Borowski A. F., Vendier L., Sabo-Etienne S., Rozycka-Sokolowska E., Gaudyn A. V., Dalton trans. 2012, 41, 14117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Early example of a chiral, rhodium-based catalyst:

- 39a. Kuwano R., Sato K., Kurokawa T., Karube D., Ito Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7614; selected examples of chiral palladium catalysts under acidic conditions: [Google Scholar]

- 39b. Wang D.-S., Chen Q.-A., Li W., Yu C.-B., Zhou Y.-G., Zhang X., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8909; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39c. Wang D.-S., Ye Z.-S., Chen Q.-A., Zhou Y.-G., Yu C.-B., Fan H.-J., Duan Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The resonance energy of benzene=36 kcal mol−1:

- 40a. Kistiakowsky G. B., Ruhoff J. R., Smith H. A., Vaughan W. E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1936, 58, 146; the resonance energy of naphthalene=61 kcal mol−1: [Google Scholar]

- 40b. Hakala R. W., Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1967, 1, 187 After the semihydrogenation of naphthalene, one aromatic ring containing 36 kcal mol−1 of resonance energy is preserved. Therefore, 25 kcal mol−1 are lost overall. [Google Scholar]

- 41.

- 41a. Widegren J. A., Finke R. G., J. Mol. Catal. A 2003, 191, 187; [Google Scholar]

- 41b. Widegren J. A., Finke R. G., J. Mol. Catal. A 2003, 198, 317; [Google Scholar]

- 41c. Dyson P. J., Dalton Trans. 2003, 2964. Important take-home message: No singular experiment exists that can unambiguously prove or disprove the homogeneous nature of the active catalyst. A definitive answer requires a series of experiments with a focus on kinetic studies. A systematic approach was introduced by Lin and Finke: [Google Scholar]

- 41d. Lin Y., Finke R. G., Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 4891. The approach was subsequently applied by the Finke group and led to reassignment of the nature of the active catalytic species for a number of prominent hydrogenation catalysts. Selected examples: [Google Scholar]

- 41e. Weddle K. S., J. D. Aiken III , Finke R. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 5653; [Google Scholar]

- 41f. Bayram E., Linehan J. C., Fulton J. L., Szymczak N. K., Finke R. G., ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 3876. However, Rothwell's active niobium and tantalum catalysts are believed to be homogeneous in nature. Review: [Google Scholar]

- 41g. Rothwell I. P., Chem. Commun. 1997, 1331. An exciting recent system: Ref. [21]. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selected recent reviews:

- 42a. McMorn P., Hutchings G. J., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 33, 108; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42b. Ding K., Wang Z., Wang X., Liang Y., Wang X., Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 5188; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42c. Heitbaum M., Glorius F., Escher I., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 4732; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 4850; [Google Scholar]

- 42d. Ding K., Uozumi Y., Handbook of Asymmetric Heterogeneous Catalysis, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2008; [Google Scholar]

- 42e. Ma L., Abney C., Lin W., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1248; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42f. Meemken F., Baiker A., Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yu J. S., Rothwell I. P., J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992, 0, 632. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reviews:

- 44a. Zhong J., Chen J., Chen L., Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 3555; [Google Scholar]

- 44b. Wei Y., Zeng X., Synlett 2016, 27, 650; selected research articles: [Google Scholar]

- 44c. Liu H., Jiang T., Han B., Liang S., Zhou Y., Science 2009, 326, 1250; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44d. Wang Y., Yao J., Li H., Su D., Antonietti M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 2362; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44e. Snelders D. J. M., Yan N., Gan W., Laurenczy G., Dyson P. J., ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 201; [Google Scholar]

- 44f. Wei Y., Rao B., Cong X., Zeng X., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9250; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44g. Huang W.-X., Wu B., Gao X., Chen M.-W., Wang B., Zhou Y.-G., Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reviews:

- 45a. Soleilhavoup M., Bertrand G., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 256; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45b. Melaimi M., Jazzar R., Soleilhavoup M., Bertrand G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10046; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 10180; synthesis of rhodium complexes: [Google Scholar]

- 45c. Lavallo V., Canac Y., DeHope A., Donnadieu B., Bertrand G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7236; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 7402. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heterogeneous catalysts have fewer active sites than single-site homogeneous catalysts, since some of the catalytic sites would be hidden inside the particle. Less than one equivalent of a strong catalyst poison should, therefore, be sufficient to completely suppress the catalytic activity of heterogeneous catalysts. See, for example, Ref. [41a].

- 47. Tran B. L., Fulton J. L., Linehan J. C., Lercher J. A., Bullock R. M., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 8441. [Google Scholar]

- 48.The roles of the Lewis acid and mass-transport phenomena in the four-phase reactor on the cyclohexene yields are complicated and remain under investigation. See Ref. [2].

- 49. Weilhard A., Abarca G., Viscardi J., Prechtl M. H. G., Scholten J. D., Bernardi F., Baptista D. L., Dupont J., ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 204. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tolerance of some sterically hindered double bonds in the hydrogenation of aryl-substituted amidoacrylic acids: Cimpeanu V., Kočevar M., Parvulescu V. I., Leitner W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1085; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 1105. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Selected references for the chemoselective hydrogenation of heteroarenes in the presence of alkenes:

- 51a. Ren D., He L., Yu L., Ding R.-S., Liu Y.-M., Gao Y., He H.-Y., Fan K.-N., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 17592; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51b. Wu J., Tang W., Pettman A., Xiao J., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 35; [Google Scholar]

- 51c. Chen F., Surkus A.-E., He L., Pohl M.-M., Radnik J., Topf C., Junge K., Beller M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11718; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51d. Adam R., Cabrero-Antonino J. R., Spannenberg A., Junge K., Jackstell R., Beller M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3216; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 3264; [Google Scholar]

- 51e. Liu Z.-Y., Wen Z.-H., Wang X.-C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 5817; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 5911. [Google Scholar]

- 52.A variety of stoichiometric reducing agents can convert pyridines to dihydro- or tetrahydropyridines. See, for example: Park S., Chang S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7720; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 7828. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Selected references for the chemoselective hydrogenation of heteroarenes in the presence of nitrile groups:

- 53a. Teodoro B. V. M., Correia J. T. M., Coelho F., J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 2529; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53b.Ref. [10a];

- 53c. Sorribes I., Liu L., Doménech-Carbó A., Corma A., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4545. [Google Scholar]

- 54.For example, the chemoselective hydrogenation of benzene or pyridine derivatives bearing nitro groups, to the best of our knowledge, remains elusive. The chemoselective hydrogenation of other heteroarenes bearing nitro groups in a remote position is, however, known. Direct hydrogenation:

- 54a. Gou F.-R., Li W., Zhang X., Liang Y.-M., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2441; selected examples of transfer hydrogenation: [Google Scholar]

- 54b. Fujita K., Kitatsuji C., Furukawa S., Yamaguchi R., Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 3215; [Google Scholar]

- 54c. He W., Ge Y.-C., Tan C.-H., Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 3244; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54d. He R., Cui P., Sun Y., Zhou H., Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 3571; [Google Scholar]

- 54e. Han Y. et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11262; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 11432. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Selected references on the hydrogenation of the N-containing ring of quinolines and isoquinolines:

- 55a.Ref. [6];

- 55b.Ref. [31b];

- 55c. Ye Z.-S., Guo R.-N., Cai X.-F., Chen M.-W., Shi L., Zhou Y.-G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 3685; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 3773; [Google Scholar]

- 55d. Chakraborty S., Brennessel W. M., Jones W. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8564; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55e. Wen J., Tan R., Liu S., Zhao Q., Zhang X., Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 3047; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55f. Chen M.-W., Ji Y., Wang J., Chen Q.-A., Shi L., Zhou Y.-G., Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4988; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55g. Chen F., Sahoo B., Kreyenschulte C., Lund H., Zeng M., He L., Junge K., Beller M., Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 6239; selected references on the hydrogenation of the less aromatic ring of other bicyclic heterocycles: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55h.Ref. [37d];

- 55i.Ref. [37f];

- 55j. Hu S.-B., Chen Z.-P., Song B., Wang J., Zhou Y.-G., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 2762. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen Z., Wannere C. S., Corminboeuf C., Puchta R., von R. Schleyer P., Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gershoni-Poranne R., Stanger A., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Clarisse D., Fenet B., Fache F., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 6587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.

- 59a. Li H., Wang Y., Lai Z., Huang K.-W., ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4446; [Google Scholar]

- 59b. He Y., Tang J., Luo M., Zeng X., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 4159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.A fascinating alternative access to functionalized cycloalkanes is being studied by the Sarlah group. Selected references:

- 60a. Southgate E. H., Pospech J., Fu J., Holycross D. R., Sarlah D., Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 922; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60b. Okumura M., Huynh S. M. N., Pospech J., Sarlah D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15910; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 16142; [Google Scholar]

- 60c. Okumura M., Shved A. S., Sarlah D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 17787; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60d. Hernandez L. W., Klöckner U., Pospech J., Hauss L., Sarlah D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4503; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60e. Wertjes W. C., Okumura M., Sarlah D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nevertheless, enantioselective hydrogenations of arenes with a directly attached functional group are rare. For an impressive study showing the tolerance of amines during the hydrogenation of carbocyclic amines, see: Yan Z., Xie H.-P., Shen H.-Q., Zhou Y.-G., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.The indicated frequencies of tolerance of the functional groups are based on a SciFinder search on benzene derivatives. The assignments were carried out as follows: “Unknown” defines all functional groups (or families thereof) whose tolerance during the hydrogenation of a benzene derivative to which they are directly attached has never been described in a synthetic study. Rare: 1–5; common: 5–10; established: >10. Conservative estimates that only include studies on product(s) with at least 50 % yield are given. Naturally, the assignments depend on the applied search parameters, the degree of freedom inherent to the families of functional groups (higher for silyl groups or amines than for halogens), and the synthetic interest. Furthermore, other factors such as poisoning effects (e.g. for [S] or [P]) can play a role.

- 63.Reviews on fluorinated compounds in agrochemistry:

- 63a. Fujiwara T., O'Hagan D., J. Fluorine Chem. 2014, 167, 16; pharmaceutical science: [Google Scholar]

- 63b. Müller K., Faeh C., Diederich F., Science 2007, 317, 1881; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63c. Purser S., Moore P. R., Swallow S., Gouverneur V., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 320; materials science: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63d. Kirsch P., Bremer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 4216; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2000, 112, 4384; [Google Scholar]

- 63e. Kirsch P., Modern fluoroorganic chemistry. Synthesis reactivity, applications, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2004, pp. 203–277. [Google Scholar]

- 64.The O'Hagan group found that the cis alignment of the polarized axial C−F bonds increases the polarity in particular. Selected previous syntheses of cis-multifluorinated cycloalkanes:

- 64a. Durie A. J., Slawin A. M. Z., Lebl T., Kirsch P., O'Hagan D., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8265; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64b. Durie A. J., Slawin A. M. Z., Lebl T., Kirsch P., O'Hagan D., Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9643; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64c.Ref. [8a]. A 1,3-diaxial alignment in acyclic motifs is prevented by a dipolar repulsion. Selected reviews:

- 64d. O'Hagan D., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 308;18197347 [Google Scholar]

- 64e. Hunter L., O'Hagan D., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 2843; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64f. Thiehoff C., Rey Y. P., Gilmour R., Isr. J. Chem. 2017, 57, 92. Even so, vicinal difluoroalkanes also possess a significant dipole moment and are sought-after motifs as well. Selected recent methods for their synthesis: [Google Scholar]

- 64g. Banik S. M., Medley J. W., Jacobsen E. N., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5000; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64h. Molnár I. G., Gilmour R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5004; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64i. Molnár I. G., Thiehoff C., Holland M. C., Gilmour R., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7167; [Google Scholar]

- 64j. Scheidt F., Schafer M., Sarie C. J., Daniliuc C. G., Molloy J. J., Gilmour R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16431; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 16669. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Selected unselective hydrogenations of fluorinated benzene derivatives:

- 65a. Fache F., Lehuede S., Lemaire M., Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 885; [Google Scholar]

- 65b. Yang H., Gao H., Angelici R. J., Organometallics 1999, 18, 2285; [Google Scholar]

- 65c. Haufe G., Pietz S., Wölker D., Fröhlich R., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 2166; review on hydrodefluorination reactions: [Google Scholar]

- 65d. Whittlesey M. K., Peris E., ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 3152. [Google Scholar]

- 66.An increase in selectivity for hydrogenation over the hydrodefluorination upon using less polar solvents had previously been observed:

- 66a.Ref. [65b];

- 66b. Stanger K. J., Angelici R. J., J. Mol. Catal. A 2004, 207, 59. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Molar fraction of H2 gas in solution at 298 K for various solvents: n-hexane: 6.6×10−4, CHCl3: 2.2×10−4; MeOH 1.6×10−4 See: Young C. J., IUPAC Solubility Data Series, Vol. 5/6, Hydrogen and Deuterium, Pergamon, Oxford, 1981, p. 120 (n-hexane), p. 247 (CHCl3), p. 194 (MeOH). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Merck Millipore Product numbers of the commercial fluorinated building blocks: tert-butyl(((cis)-4-fluorocyclohexyl)oxy)dimethylsilane (70 a): 905127; tert-butyl ((cis)-2-fluorocyclohexyl)carbamate: 905135; tert-butyl ((cis)-4-fluorocyclohexyl)carbamate (70 b): 905143; 2-((cis)-4-fluorocyclohexyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolane: 905151; all-cis-hexafluorocylclohexane (6): 905119; 1-((cis)-3,5-difluoropiperidin-1-yl)-2,2,2-trifluoroethan-1-one (7 a): 903817. The employed precatalyst (33) is also being commercialized: Product number: 904716.

- 69.The vicinal 3 J(F,H) coupling constants provide insight into the conformational structure. Large 3 J(F,Hax) values indicate an axial orientation of the fluorine substituents. Likewise, small 3 J(F,Hax) values indicate an equatorial orientation of the fluorine substituents. See Ref. [9b] for details.

- 70.Silyl groups in organic synthesis:

- 70a. Langkopf E., Schinzer D., Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 1375; silyl groups in fragrance research: [Google Scholar]

- 70b. Doszczak L., Kraft P., Weber H.-P., Bertemann R., Thriller A., Hatt H., Tacke R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 3367; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 3431; silyl groups in materials science: [Google Scholar]

- 70c. Rücker C., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 466; silyl groups in agro- and medicinal chemistry: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70d. Ramesh R., Reddy D. S., J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Olefin hydrosilylation is plagued by a low regioselectivity for 1,2-disubstituted alkenes:

- 71a. Liu J., Chen W., Li J., Cui C., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2230; the trapping of alkyl-Grignard reagents with silyl electrophiles has a low functional group tolerance. For selected modern methods on the synthesis of alkylsilanes including some cyclic examples, see: [Google Scholar]

- 71b. Chu C. K., Liang Y., Fu G. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 6404; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71c. Xue W., Qu Z.-W., Grimme S., Oestreich M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14222; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71d. Cinderella A. P., Vulovic B., Watson D. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.

- 72a. Wiesenfeldt M. P., Knecht T., Schlepphorst C., Glorius F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8297; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 8429; in our hands, complex 33 performed better than established heterogeneous catalysts, especially for the hydrogenation of alkoxy- or halosilyl-substituted arenes. Only a handful of simple silylated arenes had previously been hydrogenated. See for example: [Google Scholar]

- 72b. Kitching W., Olszowy H. A., Drew G. M., Adcock W., J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 5153. The hydrogenation of arenes bearing alkoxy- or halosilyl groups or of silylated heteroarenes had previously not been disclosed. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alkyl-Hiyama couplings and Fleming–Tamao oxidations generally require alkoxy- or halosilyl groups.

- 74.

- 74a. Wollenburg M., Moock D., Glorius F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 10.1002/anie.201810714; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 10.1002/ange.201810714; [DOI] [Google Scholar]