Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The OMERACT Safety Working Group is identifying core safety domains that matter most to rheumatic disease patients.

METHODS:

International focus groups were held with 39 inflammatory arthritis patients to identify DMARD experiences and concerns. Themes were identified by pragmatic thematic coding and discussed in small groups by meeting attendees.

RESULTS:

Patients view DMARD side effects as a continuum and consider cumulative impact on day-to-day function. Disease and drug experiences, personal factors, and life circumstances influence tolerance of side effects and treatment persistence.

CONCLUSION:

Patients weigh overall adverse effects and benefits over time in relation to experiences and life circumstances.

Keywords: OMERACT, drug toxicity, risk, patient satisfaction, clinical trials, DMARDs

BACKGROUND

Many drugs used in rheumatology carry substantial benefit and potential harms. While medication-related symptoms and adverse events are prevalent in rheumatology randomized controlled trials (RCTs), clinicians frequently underestimate their severity and focus on different priorities than patients when judging the effectiveness of medications.(1) The full spectrum and combination of potential harms are important to capture, given that adverse drug reactions cause considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide.(2)

Current approaches to safety monitoring depend heavily on healthcare professionals, despite known limitations including under-reporting and discordant perspectives of patients and clinicians.(3) Although regulatory authorities in Europe and the United States (US) call for inclusion of patient-reported information of benefit and safety, there is limited understanding of what matters most to patients regarding disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) safety. While a patient-based reporting system has been developed to capture symptoms and adverse events from patients in cancer clinical trials (4), no standardized approach currently exists for rheumatology trials. To date, there has been little effort to systematically collect information directly from patients about side effects that concern them.

Patients frequently report they experience side effects including upset stomach, fatigue, nausea, and GI distress when taking medicines for rheumatic diseases.(5–9) Symptomatic adverse events, also known as side effects, are increasingly recognized as an important contributor to poor adherence and can lead to patient-initiated dose reduction and early discontinuation. Rheumatology RCTs require substantial time, effort, and resources, and rely on patient altruism. It is essential to assess the range of potential benefits and harms associated with an intervention and include safety outcomes that are relevant and meaningful to patients. The OMERACT Safety Group was re-established at OMERACT 2016 to identify core domains for safety aspects that matter most to patients in rheumatology trials.(10)

METHODS

As part of a larger mixed-methods study, we present here the qualitative findings from our a priori protocol which was registered in March 2017 with the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (http://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/details/1120?result=true). An initial scoping review by this group in 2016 revealed that safety has differing connotations and reflects a spectrum of events. An optimal method and language to assess patient-valued safety aspects in trials has not been identified.

To gain insight into patient priorities, six semi-structured focus groups were held with inflammatory arthritis (IA) patients in Canada, US, and Australia from March-May 2018, facilitated by an experienced qualitative researcher. According to a pre-specified interview schedule, participants were encouraged to describe their experiences taking DMARDS for their arthritis, as well as perceptions of benefit and potential harm. Ethical approval for the focus groups was obtained (Bingham: NA00066663, Bykerk: 2018–0233, Bartlett: 2018–4404, Kelly: LNR/16/LPOOL/701 and LNRSSA/17/HAWKE/429). Groups were recorded and transcribed. We conducted a targeted and pragmatic analysis based in grounded theory to descriptively and thematically summarize discussions. (11)

Initial results were presented at the OMERACT Pre-Meeting (Improving Risk-Benefit Assessment of Drugs with an Emphasis on Patients and Their Perspective) on May 13 and 14, 2018 in Terrigal, New South Wales, Australia (described elsewhere ANDERSEN 2018). Attendees broke into 5 groups; seating was pre-arranged to ensure the inclusion of diverse perspectives and stakeholders within groups. Patient research partners reported results of these discussions to all attendees at a report-back session.

RESULTS

Thirty-nine adults with IA participated in the initial focus groups from the US (12 women, 2 men; Maryland and New York), Canada (8 women, 2 men; Ontario, Quebec, and Manitoba), and Australia (11 women, 4 men; New South Wales).

In brief, four themes were identified (Table). First, almost all participants reported experiencing many DMARD side effects that are often termed “nuisance side effects”. Although “nuisance” side effects are often not viewed by trialists and treating clinicians as problematic, patients reported they had a considerable cumulative impact on quality of life but were seen as “the price you pay” for improvement. Almost all patients indicated that the impact on day-to-day physical and social function mattered more to them than physiologic manifestations. Most learned to live with DMARD side effects; however, some lives were completely changed. Many reported that the disabling and persistent side effects were managed using a range of behavioral and nutritional strategies (e.g., talk less to avoid irritating a mouth ulcer, exercise, earlier bedtime, reduced participation, yogurt, anti-diarrheal over-the-counter medications) to attenuate common side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal distress, mouth ulcers, fatigue). The failure of self-management and the considerable cumulative burden of side effects led to increased frustration and helplessness; these were key reasons some decided to discontinue a medication.

Table.

Themes and illustrative quotes identified in inflammatory arthritis participants regarding DMARD safety concerns.

| Theme | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|

| Patients and clinicians view side effects differently; “nuisance” side effects persist and can have a substantial cumulative impact and often lead to patient-initiated dose reductions and discontinuation |

I feel like I can’t think anymore, and that really affects work and that’s

my biggest problem. I can push through the pain and I can sometimes push through the fatigue, but I can’t think

clearly. I just can’t do my job, and that’s been the biggest struggle for me. Female,

USA When you do bring up a concern like “Well, I’ve got really bad headaches…And [MD says] “Oh well that’s a hard problem to deal with.” It gets kind of sloughed off. [Female, Canada] Started out with nausea, and for a long time it wasn’t too bad. But the last 3 years, I just felt nauseated 24/7, even with the injection --nausea, headache, digestive issues. And I just took myself off it…and I feel a whole heck of a lot better. [Female, Canada] |

| Patients have difficulty sorting out side effects from other factors |

I thought, it can’t be the medication. I didn’t eat properly today.

I’ve had 13 cups of coffee. I need to go home and get some food in me… and all kinds of reasons for what

was happening, other than [the medication]. [long pause] It was the medication. Female,

Canada Honestly, sometimes I don’t think about it …I would not have said to you, “Oh, I have lost my hair.” But you know what? I’m cleaning out my drain … I’m cleaning a lot of hair out of my drain. But I wouldn’t think to report it. Female, USA |

| Different DMARDS elicit different safety concerns |

(I worry about) bad things that can happen in you that you can’t

see.” Male, Canada … and then [with] going through all the side effects, but you want me to take this forever? You know, what, I’m 26 and I’m supposed to just take this forever now even though you’ve told me the effects it’s going to have my liver, etc. …I am not satisfied with just taking the medications that they’re giving me for however long. I need to know there’s some sort of end date. Female, Australia |

| Concerns are influenced by disease and medication experiences, and individual and social factors |

When I first was diagnosed, I didn’t think I was going to live as long as I did.

That’s how bad I felt. So, the side effects… just have to step aside right now. Because I look at the

positive part of it. I can walk four blocks and it don’t bother me.” Female,

USA I’m definitely worried about the long-term effects… if I wanted to have a family, how would I do that? …And the doctors always saying that that’s going to be fine and manageable. And I know that obviously other people do it. …But it is something that I think about. Female, Australia |

Second, almost all patients reported difficulty with symptom attribution, and would only identify medications as a potential cause after first considering lifestyle, current health, and other life circumstances. Within each group, patients were often surprised when others described side effects (“I didn’t know that could be a side effect. I noticed my drain was full of hair, but never thought it might be the medication.”) Many patients were uncomfortable discussing side effects to trialists or providers out of concern they would be labelled as “whiners”, removed from a trial, or be switched to an inferior drug.

Third, participants reported that different drugs elicited different safety concerns. Methotrexate (MTX), often the first treatment, was perceived as the most worrisome; several noted that the initiation of MTX as a first-line treatment often resulted in toxicity concerns being emphasized when the patient is still coping with accepting their diagnosis. Patients noted that while their physicians embrace MTX use, patients are often initially terrified to use it. In all groups, MTX was largely viewed as a common enemy, uniting the group. Conversely, the first mention of steroid use divided groups into two camps, eliciting strong opinions that were either testimonies to the benefits or admonitions against use. One patient noted “prednisone is the new smoking”, reflecting both a perceived stigma and difficulty to discontinue once started. Drug switches, particularly when treatment was escalated to include biologics, were embraced by patients when their disease was poorly controlled. However, switches to generic medications when disease was well controlled were stressful and evoked concerns about loss of control. Safety concerns for DMARDs are influenced by disease and medication experiences, personal and life circumstances, and exposure to stories from other patients.

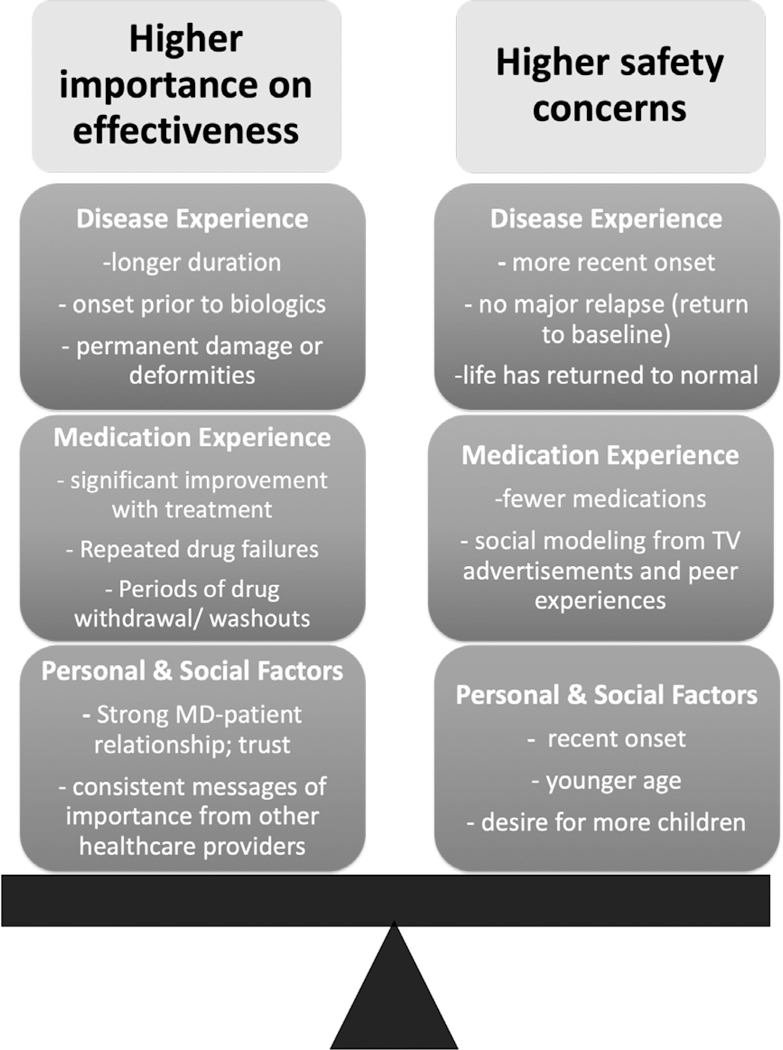

Fourth, participants described how they weighed the safety versus effectiveness of DMARDS to decide if the medication was optimal for them (Figure). Patients with higher safety concerns tended to be younger, had more recent onset of IA, had tried fewer medications, returned more quickly to pre-diagnosis function with treatment, and had not experienced a major relapse. Conversely, patients who were willing to tolerate lower perceived levels of drug safety in favor of higher effectiveness tended to have long-standing disease, greater disability, and greater improvement in function with treatment. Patient characteristics (current living situation and roles), disease experience (e.g., severity of disease at its worst, number of failed medications), and social modeling (e.g., reports on social media) influenced the way in which patients viewed adverse events and side effects.

Figure 1.

The balance of safety and effectiveness concerns in people with inflammatory arthritis.

DISCUSSION

These results generated considerable discussion among Pre-Meeting attendees. Many of the patient research partners had strong emotional reactions during the presentation, and almost all reported feeling validated and reassured that these issues were being acknowledged. Several attendees reported that these results highlighted the cumulative impact and interference of treatments as more meaningful to patients than the discrete adverse events that are typically captured in drug trials, (i.e., physiological manifestations), suggesting a paradigm shift may be warranted.

Several themes emerged in the report-backs. There was consensus that the current dichotomization of side effects (i.e., “nuisance” vs. important) is judgmental and often arbitrary, potentially stigmatizing to patients, and does not reflect patient priorities. Some note that clinicians often use the term “nuisance side effects” to help diminish patient concerns; there is also discomfort discussing side effects when it is unclear how they can be mitigated. There was consensus that further research is needed to identify patient-relevant questions on drug safety concerns and ways to create conversations that encourage and support broader discussion. In clinical trials, it will be important to measure not only how an individual feels and functions, but also the impact on everyday life (e.g., “How is the medication affecting you? What have you or others noticed since starting the drug?”). Given that current life circumstances play a major role in the patient’s ability and willingness to tolerate specific side effects (e.g., fatigue, nausea, diarrhea), there is a need to measure and incorporate contextual factors when interpreting results of drug trials. Future trials and longitudinal studies should query patient satisfaction with the medication, and move towards a systematic and standardized approach to capture this important data. For example, in oncology, the five “WIWI Questions” (“Was it worth it? Would you do again? Did quality of life improve? How satisfied are you with outcome? Would you recommend to others?”) have been used to assess how patients view the benefits and costs of treatment.

Our findings and discussion among attendees prompted discussions within OMERACT and modification of the OMERACT filter(12, 13). Version 2.1 now explicitly includes “Benefits and Harms” as a potential core domain to capture both the intended and unintended effects of interventions. It is anticipated this domain will be recommended for inclusion in many future OMERACT core domain sets. Additional work by the Safety Group in other countries is needed to confirm and extend these findings, and the results of this qualitative work will feed into future quantitative and qualitative phases (namely, Delphi and consensus work) towards agreement on core domains.

Acknowledgement

Funding: OMERACT is an organization that develops and validates outcome measures in rheumatology randomized controlled trials and longitudinal observational studies and receives arms-length funding from 12 sponsors.

• RC: The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital (RC) is supported by a core grant from the Oak Foundation (OCAY-13–309).

• COB/MKJ and this work supported in part by NIH-AR070254 Core B, and the Camille Julia Morgan Arthritis Research and Education Fund.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval for the focus groups was obtained by investigators in the United States (US) at Johns Hopkins University (Bingham: NA00066663), Hospital for Special Surgery (Bykerk: 2018–0233); in Canada at McGill University (Bartlett: 2018–4404), and in Australia through South Western Sydney Local Health District and Royal North Shore Hospital (Kelly: LNR/16/LPOOL/701 and LNRSSA/17/HAWKE/429).

Disclosures:

LSS has nothing to disclose with relation to this manuscript other than serving on the Executive Committee of OMERACT and functioning as Chair of the Finance committee and serving as Co- Chair of the Business Advisory Committee.

AK has no conflicts of interest to declare

RC has nothing to disclose with relation to this manuscript

PB has nothing to disclose in relation to this manuscript.

COB, LSS, PT, and LM are members of the OMERACT executive committee, but do not receive remuneration for their roles. BS receives financial support from OMERACT.

Conflict of Interest:

Contributor Information

Kathleen M Andersen, Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Canada.; Musculoskeletal Statistics Unit, The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Ayano Kelly, Canberra Rheumatology, Canberra, ACT, Australia ; College of Health and Medicine, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia ; Centre for Kidney Research, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW, Australia .

Anne Lyddiatt, Patient Partners, Ingersoll, Canada..

Clifton O. Bingham, III, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Vivian P. Bykerk, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, USA.

Adena Batterman, Department Social Work Programs, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY USA.

Joan Westreich, Department Social Work Programs, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY USA.

Michelle K. Jones, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Marita Cross, Institute of Bone and Joint Research-Kolling Institute, University of Sydney; Rheumatology Department, Royal North Shore Hospital.

Peter Brooks, Centre for Health Policy, School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.; Northern Health, Epping Victoria.

Lyn March, Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Institute of Bone and Joint Research, Kolling Institute, Northern Sydney Local Health District, St Leonards, NSW, Australia; Department of Rheumatology, Royal North Shore Hospital, Reserve Road, St Leonards, NSW, 2065, Australia.

Beverly Shea, Clinical Investigator, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Adjunct Professor, School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Peter Tugwell, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, and School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa; Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa.

Lee S. Simon, SDG LLC, Cambridge, MA 02138.

Robin Christensen, Professor of Biostatistics and Clinical Epidemiology; Musculoskeletal Statistics Unit, The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital; & Department of Rheumatology, Odense University Hospital, Denmark..

Susan J. Bartlett, Professor, Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Adjunct Professor, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

References

- 1.Basch E The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med 2010;362:865–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Safety of medicines: A guide to detecting and reporting adverse drug reactions. Geneva, Switzerland; 2002. Contract No.: Document Number|. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee AK, Okun S, Edwards IR, Wicks P, Smith MY, Mayall SJ, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in safety event reporting: Prosper consortium guidance. Drug Saf 2013;36:1129–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA, Reeve BB, Castro KM, Rogak LJ, et al. Validity and reliability of the us national cancer institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (pro-ctcae). JAMA oncology 2015;1:1051–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Angelo S, Carriero A, Gilio M, Ursini F, Leccese P, Palazzi C. Safety of treatment options for spondyloarthritis: A narrative review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2018;17:475–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gawert L, Hierse F, Zink A, Strangfeld A. How well do patient reports reflect adverse drug reactions reported by rheumatologists? Agreement of physician- and patient-reported adverse events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis observed in the german biologics register. Rheumatology 2011;50:152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasma A, van ‘t Spijker A, Luime JJ, Walter MJ, Busschbach JJ, Hazes JM. Facilitators and barriers to adherence in the initiation phase of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (dmard) use in patients with arthritis who recently started their first dmard treatment. J Rheumatol 2015;42:379–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linden C, Bjorklund A. Living with rheumatoid arthritis and experiencing everyday life with tnf-alpha blockers. Scand J Occup Ther 2010;17:326–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodacre LJ, Goodacre JA. Factors influencing the beliefs of patients with rheumatoid arthritis regarding disease-modifying medication. Rheumatology 2004;43:583–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klokker L, Tugwell P, Furst DE, Devoe D, Williamson P, Terwee CB, et al. Developing an omeract core outcome set for assessing safety components in rheumatology trials: The omeract safety working group. J Rheumatol 2017;44:1916–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boers MK JR l Tugwell P; Beaton D; Bingham CO III; Conaghan PG et al. The omeract handbook. [cited September 20, 2018]; Available from: https://omeract.orgresources.

- 13.Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d’Agostino MA, et al. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: Omeract filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:745–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]