Significance

Without social and emotional support, adolescent students who have recently made the difficult transition to middle school experience decreased social belonging, waning academic performance, and increased risk of dropping out. This randomized field trial, conducted at scale across a Midwestern school district, reveals how a psychologically precise intervention for students supported transitioning sixth graders. Intervention materials taught students that middle school adversity is common, short-lived, and due to external, temporary causes rather than personal inadequacies. As a result, students realized improved social and psychological well-being, fewer absences and disciplinary infractions, and higher grade point averages. Implemented at scale, this intervention holds potential to help to address the widespread academic underperformance by the nation’s transitioning middle school students.

Keywords: educational intervention, middle school transition, academic achievement, social belonging, student engagement

Abstract

The period of early adolescence is characterized by dramatic changes, simultaneously affecting physiological, psychological, social, and cognitive development. The physical transition from elementary to middle school can exacerbate the stress and adversity experienced during this critical life stage. Middle school students often struggle to find social and emotional support, and many students experience a decreased sense of belonging in school, diverting students from promising academic and career trajectories. Drawing on psychological insights for promoting belonging, we fielded a brief intervention designed to help students reappraise concerns about fitting in at the start of middle school as both temporary and normal. We conducted a district-wide double-blind experimental study of this approach with middle school students (n = 1,304). Compared with the control condition activities, the intervention reduced sixth-grade disciplinary incidents across the district by 34%, increased attendance by 12%, and reduced the number of failing grades by 18%. Differences in benefits across demographic groups were not statistically significant, but some impacts were descriptively larger for historically underserved minority students and boys. A mediational analysis suggested 80% of long-term intervention effects on students’ grade point averages were accounted for by changes in students’ attitudes and behaviors. These results demonstrate the long-term benefits of psychologically reappraising stressful experiences during critical transitions and the psychological and behavioral mechanisms that support them. Furthermore, this brief intervention is a highly cost-effective and scalable approach that schools may use to help address the troubling decline in positive attitudes and academic outcomes typically accompanying adolescence and the middle school transition.

Adolescence introduces a dynamic period of human development, presenting both opportunities and challenges for positive physiological, psychological, social, and cognitive growth (1). A defining feature of this developmental stage is a heightened sensitivity to social acceptance, social comparisons, and sociocultural cues (2, 3). Amid increasing self-awareness and independence, nonkin social networks become larger, more competitive, and more influential, leaving adolescents to find their place in an expanding social world at the same time they are only beginning to develop competencies to form meaningful and long-lasting relationships and connections to important institutions like schools. In particular, increased sensitivity to social acceptance during this period can raise questions concerning adolescents’ sense of belonging or their perception of having positive connections with peers, trusted adults, and important institutions (4). Since belonging is an essential human need (5), difficulties “fitting in” during adolescence can have significant and lasting negative consequences (6).

The developmental challenges of adolescence are often compounded by the transition to the new social and academic environment of middle school—a particularly disruptive and nearly universal experience in the United States (7). This transition typically entails the move from a familiar neighborhood elementary school to a new educational environment that is farther from home, larger, more bureaucratic, less personal, and more formal and evaluative (8). Though middle schools were originally designed to meet the specific educational needs of adolescents and to prepare them for the academic rigors of high school, stage–environment fit theory highlights important mismatches between adolescents’ developmental needs and the social–organizational context of middle school (2). The typical middle school environment emphasizes academic evaluation and competition, often reflected in the onset of letter grades and differentiation between more and less advanced classes, which encourage negative social comparisons while students are forming their academic identities (2, 8). Social acceptance by peers and caring relationships with adults outside of the home are of particular importance to adolescents’ positive development, and the physical transition disrupts prior school-based peer networks. Teacher–student relationships tend to become more distant, and potentially negative, as greater emphasis is placed on teacher control and discipline (2, 9, 10). Despite the best intentions of teachers and school leaders, the poor stage–environment fit of middle schools thus threatens students’ academic and relational belonging in school.

Belonging concerns amid the transition to middle school contribute to decreases in academic engagement and well-being during this period. Research documents declining academic performance (7, 11), waning intrinsic motivation (2), rising disciplinary infractions (10), and emerging mental health problems (3) during middle school. Such trends reflect relatively common struggles of adolescents in school (2). As the implications of school performance for future educational and occupational attainment increase, these declines in adolescents’ academic performance and well-being have troubling long-term implications (2, 8). On the other hand, this formative period of adolescence also offers a unique opportunity to challenge and change the potentially damaging personal narratives that students develop as they confront academic and relational adversities that can undermine their sense of belonging. In lieu of recent costly interventions to restructure middle schools (7), there may be ways to enhance psychological supports that schools can apply to reduce the problem of nonbelonging in the middle school context.

Social–Psychological Intervention to Improve School Belonging for Middle School Students.

Although declining academic engagement in middle school is rooted in developmental and social–organizational challenges, the importance of students’ sense of belonging in these processes provides a potential point of leverage for mitigating these trends. Many of the challenges of middle school become detrimental through students’ perception that they do not fit in at school. For instance, when students encounter cues that raise ambiguity about their belonging in middle school, such as not being able to find anyone to sit with in the lunchroom, they may view these problems as atypical (i.e., they are the only ones feeling this way) and attribute tenuous belonging to their own permanent inadequacies (4). This can further demotivate students and lead them to interpret new experiences in psychologically harmful ways (12, 13) as anxiety becomes the leading emotion (14). Thus, one way to intervene to promote belonging could be by targeting these attribution errors and encouraging students to reappraise their perspective on their difficulties (13, 15, 16). Proactively teaching students to make targeted shifts in perspective can have substantial impacts on students’ self-assessments and motivation in school (4).

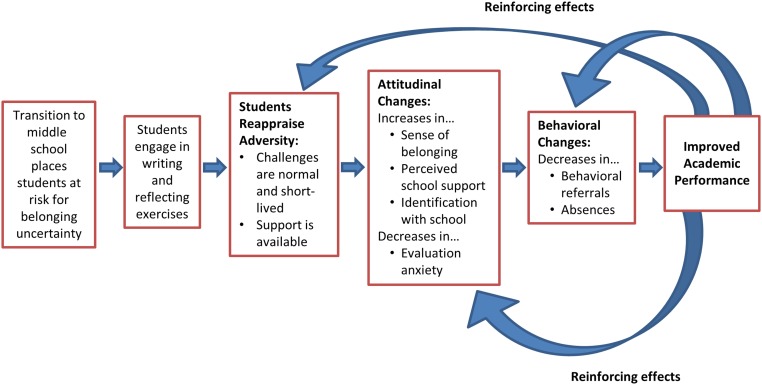

In this study, we test an intervention for middle school students that helps them reappraise adversity related to common worries that adolescents have concerning belonging in school. The hypothesized theory of change is summarized in Fig. 1. The key messages of the intervention are that worries about students’ belonging in middle school are normal, that they are short-lived, and that support is available. When students understand belonging worries as common and surmountable, they are better able to interpret adversity as nonthreatening and maintain a motivational orientation that supports better performance (4). The hypothesized immediate impact is that students will have greater well-being in the form of more positive attitudes about school. Increased positive attitudes reduce the cognitive resources devoted to stress management, freeing students’ mental capacity for academic work (12, 14). Next, greater perceived fit at school can lead to changes in critical behavioral indicators of academic disengagement, including absences from school and instances of acting out (10). Finally, over time, shifts in student beliefs and behaviors improve academic performance, which then reinforce those positive beliefs (14, 17). This redirected, recursive cycle has the potential to foster long-term improvements in academic achievement and engagement in school (10, 14, 17).

Fig. 1.

Theory of change. This figure depicts the recursive psychological and behavioral processes that the intervention is intended to set in motion to promote a sustained positive effect on academic and well-being outcomes.

This hypothesized theory of change draws on research among college students that supports the efficacy of targeted reappraisal messages for at least some social groups (13, 15, 16, 18, 19). However, to date, most evidence is limited to selective universities, contexts in which a relatively small group of high-achieving young adults is navigating elite postsecondary institutions, and belonging concerns emerge only for specific, underrepresented groups. It is therefore unclear whether comparable reattribution messages are beneficial during adolescence and the widespread social challenges of middle school. The message that belonging concerns are common and surmountable may be even more critical during such a sensitive period. However, developmental features of adolescence present unique challenges to the external messages of interventions (1), and broader issues of stage–environment fit in middle school may mute the benefits of intervening on belonging.

In addition to the question of the effectiveness of promoting belonging during this developmental period, the unique context of the middle school transition highlights 2 central theoretical questions. The first is the mechanisms of interventions to promote school belonging, especially in terms of ongoing processes that support sustained benefits. Preliminary evidence on belonging in college suggests intervention impacts may operate through institutional engagement, such as likelihood of living on campus (16). But even as research begins to elucidate processes integral to college belonging, we should not expect all of the same mechanisms to apply in early adolescence since theorized processes depend on features of the educational context. An instructive example is students’ connection to their teachers. In college contexts where interactions are infrequent and diverse, initiating any contact with a professor may be valuable (16), but middle school students are placed in frequent and involuntary contact with teachers who hold much more influence over students’ day-to-day lives. Student–teacher relationships also tend to be less positive and personal than in elementary school (where students most often interact with only one teacher), as middle school teachers set the tone for increased academic evaluation and more severe discipline for misbehavior (2, 10). Thus, building positive relationships with teachers is a key to experiencing a safe and more supportive educational environment, with potential consequences for whether and how students engage in middle school. As reflected in Fig. 1, this leads to developmentally specific hypotheses about attitudinal and behavioral mechanisms, especially related to school discipline.

Another key theoretical question raised by belonging interventions in middle school is the scope of the impacts of these interventions: For whom are such messages beneficial? In research in postsecondary settings, benefits are typically observed for groups at greatest risk for belonging worries, such as African American students in an elite institution (6) and students from lower-income backgrounds at a flagship state university (16). Theoretically, belonging concerns in these university contexts are consistent with a “cultural mismatch” hypothesis, which suggests that inequality is produced when cultural norms in mainstream university institutions do not match the norms prevalent among social groups who are underrepresented in those institutions (20). Though majority university students may experience doubts about their belonging, these concerns are likely less acutely felt than specific, group-based worries of racial/ethnic minority or first-generation students that “people like me” do not belong (16). These theories regarding belonging at the university transition contrast markedly with those related to the middle school transition, which specify a near-universal negative stage fit involving all students navigating new educational environments that do not fit their developmental stage (2).

It is unclear whether racial or socioeconomic factors moderate interventions to promote belonging at the middle school transition. Given social stereotypes apply to adolescents just as they do to young adults (21), belonging interventions might confer group-specific benefits for disadvantaged and underserved groups of all ages. However, these differences might instead be muted by more universal concerns about belonging experienced during adolescence and at the transition to middle school, or group differences may vary across multiple local middle school contexts. Given ambiguity in potential explanations for moderation effects, it is important to thoroughly test our theory of belonging during the middle school transition for all students and for particular groups of students.

In summary, the challenges students experience in middle school provide an opportunity to address academic disengagement by reappraising middle school–specific concerns about belonging as normal and temporary. Doing so at this critical developmental period (1) may set students on a more positive trajectory for success precisely at the time when students typically begin a decline in academic engagement and performance at the start of middle school that continues through high school and college (11). Moreover, the unique developmental and social organizational context of middle schools foregrounds important theoretical questions about school belonging and development: whether adversity reappraisal messages are meaningful at this stage, what the various mechanisms that support sustained benefits over time are, and how widely any benefits may apply. To test and explore these questions, we conducted a large-scale randomized field trial in which we implemented a middle school–specific intervention, measured developmentally appropriate attitudinal and behavioral mechanisms, and did so at the scale of an entire urban school district to test how intervention effects might differ across different groups of students and school contexts.

The Current Study.

Since research done with college students on belonging may not directly apply to the middle school experience, we extend the broader theory underlying these approaches by testing a belonging intervention designed specifically for students making the transition to middle school, a near-universal milestone when structural changes and identity formation threaten belonging. We conducted our study in all middle schools in a Midwestern public school district (1,304 sixth-grade students). The largest racial/ethnic groups in the district’s total K–12 student population were white (44%), Latino (19%), African American (18%), and Asian (9%). Standardized test scores for the district were average among all districts in the nation, but there were very large achievement disparities for historically underserved groups, including African American and Latino students (see SI Appendix for details). Within each of the 11 schools, students were randomly assigned to the intervention or a control condition. The control exercises included the same amount of reading and writing but asked students to write about neutral middle school experiences that were not related to school belonging.

We collected pre- and postintervention survey data on students’ reported social and emotional well-being and official school transcripts of student attendance, disciplinary records, and grades. We used these measures to assess the intervention’s impact on theoretically important psychological, behavioral, and academic outcomes. We also tested how the psychological and behavioral measures served as mechanisms explaining intervention effects on academic achievement. Finally, we used demographic information to test theorized differences in intervention impacts by racial/ethnic groups and by gender.

Results

Balance Between Conditions on Preintervention Variables.

All group differences on baseline data for the control and intervention groups were not statistically significantly different from zero and were smaller than 0.1 SD, indicating successful randomization to condition (for individual experimental balance tests, see SI Appendix, Table S1).

Multiple Regression Models of Intervention Effects.

Analytic details.

To assess the effect of assignment to the belonging intervention, we regressed each outcome of interest on the following centered contrast coded independent variables: experimental group (+1 for intervention and −1 for control), historically underserved minority group (+1 for African American, Latino, Native American, and multiracial students and −1 for white and Asian students), gender (+1 for female and −1 for male), and all of the 2- and 3-way interactions between those variables. We also included a set of covariates, including English language learner status, disability status, free or reduced-price lunch eligibility (a proxy for family economic disadvantage), a preintervention measure of each dependent variable, and school fixed effects. Random assignment at the student level, blocked by school, greatly reduces the threat of bias in the study design, and the inclusion of additional covariates serves to increase the precision of each estimate. To account for cases missing baseline covariates, we used full information maximum likelihood methods for all analyses. Here, we report on the estimated effects of the intervention, and full model results are included in SI Appendix, Table S2.

Results: Manipulation check.

To assess whether the intervention exercises had the intended immediate effect on students’ reappraisal of adversity (Fig. 1), we included manipulation check questions for students at the end of each writing exercise (SI Appendix, Appendix B) focusing on academic worries that undermine school belonging (exercise 1) and relational worries (exercise 2). In each case, 2 questions assessed whether the students’ assessments of previous sixth grade students reflected the messages that such worries are 1) common and 2) temporary. Results of these manipulation checks indicated that intervention group students reappraised both academic and relational worries as expected by rating previous students’ worries as more common in sixth grade and less common in seventh grade than the control group (details in SI Appendix).

Results: Main outcomes.

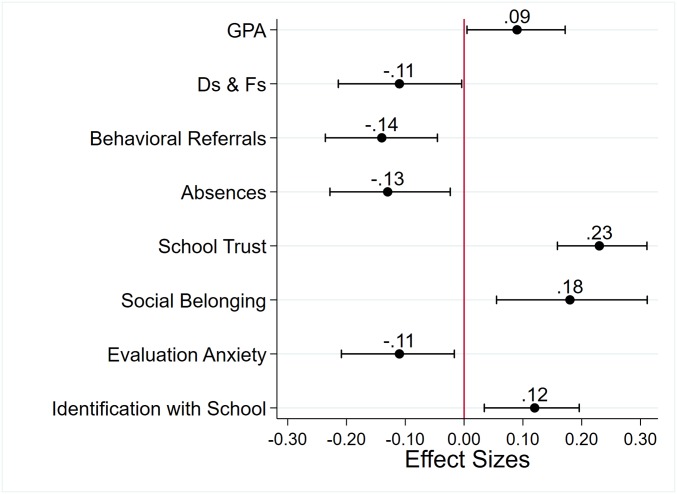

Results for students’ well-being were in the expected directions, with students in the intervention group reporting higher levels of school trust (z = 4.37, P < 0.001, β = 0.11), social belonging (z = 3.37, P = 0.001, β = 0.10), and identification with school (z = 2.80, P = 0.006, β = 0.06) and lower levels of evaluation anxiety (z = −2.74, P = 0.005, β = −0.07) at the end of the school year. Fig. 2 displays Cohen’s d estimates with 95% confidence intervals of the effect of intervention on each outcome. Results presented for individual outcomes using school fixed effects are consistent with results from multilevel models in which students are nested in schools.

Fig. 2.

Intervention effects on academic, behavioral, and well-being outcomes. Dots are Cohen’s d effect sizes; bars are 95% confidence intervals. SEs are clustered at the school level. Models also include controls for gender, race, prior achievement, disability status, free or reduced-price lunch eligibility, English language learner status, and 2- and 3-way interactions for race, gender, and experimental group. Ds & Fs = number of Ds and Fs received.

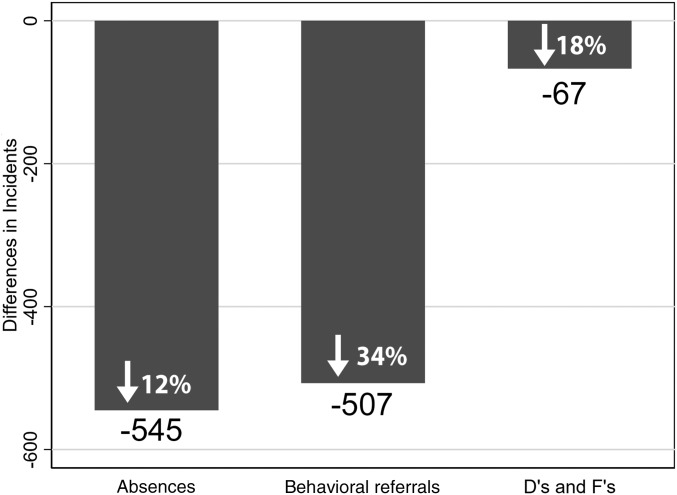

The intervention had substantively and statistically significant effects on students’ grade point averages (GPAs) and the number of failing (D and F) grades. Results were in the expected direction, with students in the intervention group having higher GPAs (z = 2.08, P = 0.038, β = 0.03) and fewer Ds and Fs (z = −2.04, P = 0.042, β = −0.06). There were also effects on behavioral outcomes, such that students in the intervention group received fewer behavioral referrals (z = −2.89, P = 0.004, β = −0.39) and had fewer absences (z = −2.41, P = 0.016, β = −0.49). Behavioral referral results are robust to estimation with a negative binomial regression model. The magnitude of these impacts is small but meaningful. In aggregate, the intervention group experienced 545 fewer absences, 507 fewer behavioral referrals, and 67 fewer D or F grades across the school district during the academic year following implementation of the intervention (Fig. 3). These intervention impacts correspond to a 12% reduction in absences, a 34% reduction in behavioral referrals, and an 18% reduction in receiving Ds or Fs, relative to control group levels, during the measurement period.

Fig. 3.

Differences in number and rate of absences, behavioral referrals, and Ds and Fs between intervention and control groups. The figure represents unadjusted aggregate intervention minus control group differences. Behavioral referrals and absences for each student are top-coded at 35 and 45 incidents, respectively, to account for outliers.

Estimated interactions with student demographics were generally in the favor of greater benefits for racial/ethnic minority and male students but not precise enough to reject the null hypothesis of no difference despite the large sample size in this study. This may in part reflect relatively broad impacts (and smaller group differences) of the belonging message at this developmental stage when the threat to belonging is a largely universal experience.

Structural Equation Model.

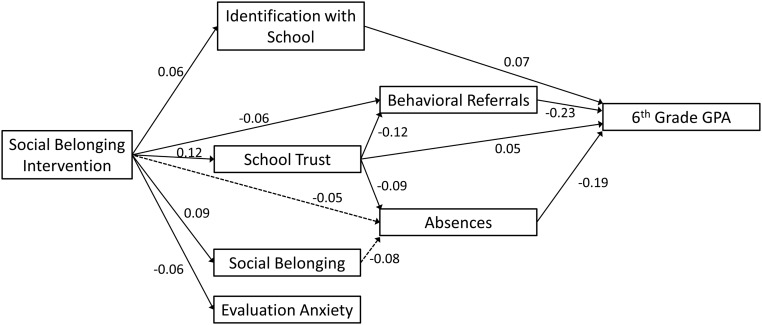

To assess mechanisms of intervention impacts, we tested elements of our theory of change (Fig. 1) using structural equation modeling (Fig. 4). In this model, we tested if the effect of the intervention on students’ GPAs was mediated by effects on students’ attitudes (school trust, social belonging, evaluation anxiety, identification with school) and by effects on students’ behaviors (number of behavioral referrals and absences).

Fig. 4.

Empirical path model. Path coefficients are standardized. SEs are clustered at the school level. Solid lines indicate path coefficients statistically significant at P < 0.05. Dashed lines indicate path coefficients statistically significant at P = 0.05 to P < 0.10. Path coefficients at P = 0.10 or greater are not shown, but all paths between variables were included in the model. The model also included controls for gender, race, prior achievement, disability status, free or reduced-price lunch eligibility, English language learner status, and 2- and 3-way interactions for race, gender, and experimental group. Both student well-being measures and behavior measures were allowed to covary.

All predictors in the individual outcome models were included as predictors of each variable in the structural equation model (i.e., intervention; race; gender; interactions between intervention, race, and gender; and demographic covariates). The model included postintervention student behaviors and survey measures of student attitudes as mediators. We report estimates from a simple model omitting preintervention measures of those variables, as including these covariates did not alter conclusions. Our theory informs a fully saturated structural equation model which imposes no restrictions of possible paths. Direct intervention effects on student attitude measures were comparable to regression results reported above (SI Appendix). Below, we focus on the mediation pathways, but full model results are reported in SI Appendix and in SI Appendix, Table S4.

Well-being as a predictor of student behaviors.

Our theoretical model posits that positive student attitudes lead to fewer behavioral referrals and absences. In support of that hypothesis, we found that higher school trust was associated with fewer behavioral referrals (z = −2.46, P = 0.014, β = −0.12) and fewer absences (z = −2.34, P = 0.019, β = −0.09). Higher levels of social belonging were marginally associated with fewer absences (z = −1.73, P = 0.083, β = −0.08).

Well-being and student behaviors as predictors of GPA.

Four independent variables in the model significantly predicted GPA: identification with school (z = 4.08, P < 0.001, β = 0.07), school trust (z = 2.17, P = 0.030, β = 0.05), number of behavioral referrals (z = −5.46, P < 0.001, β = −0.23), and number of absences (z = −8.55, P < 0.001, β = −0.19).

Indirect effects and mediation.

We tested 2 types of indirect pathways. We first tested the total indirect effect of intervention through well-being measures on behavior outcomes (i.e., behavioral referrals and absences). The effect on behavioral referrals was mediated by well-being pathways (z = −2.50, P = 0.013); the combined indirect effects were 23% of the total effect of the intervention. The effects on absences were also mediated by well-being (z = −2.48, P = 0.013)—these indirect effects were 20% of the total intervention impact. Second, we tested the total indirect effect of intervention through well-being and behavior variables on GPA. These variables mediated the total impact on GPA (z = 2.88, P = 0.004), and these indirect effects were 80% of the total effect, suggesting that much of the effect of the belonging intervention worked through changes in student attitudes and behaviors. Recognizing limitations of the SEM approach for identifying causal mediation effects due to confounding influences (22), we conducted supplemental tests of the average causal mediation effects for each potential mediator (SI Appendix), which led to a similar conclusion.

Discussion

The belonging intervention we fielded helped adolescent students making the transition to middle school adopt a mindset that worries about belonging are common among their peers and can be overcome with time and effort. In doing so, the intervention unlocked greater potential for positive well-being and academic outcomes for students. Our results trace how changes in students’ perspectives about school and stronger engagement in school contribute to improved academic performance.

There are several important implications of these findings. First, although previous studies have focused largely on college students, we show that reappraising adversity can be effective during the earlier, and critical, period of adolescence. It is notable that brief reappraisal messages were beneficial given 2 particular challenges of adolescence: 1) a wide array of developmental and environmental belonging challenges that may overwhelm any messages to the contrary (2, 3) and 2) adolescents’ resistance to outside messages about how they should think, especially from adults (1). However, effectiveness of the adversity reappraisal approach demonstrates the value of targeted, contextually appropriate messages both for psychological well-being, as reflected in lasting increases in students’ fundamental attitudes about their school and their place within it, and for ultimate academic success. Because we conducted this test in an entire district that shares demographic and achievement similarities with the nation as a whole (SI Appendix), these benefits may apply in many other settings, but future research is needed to directly test the broader generalizability of these results.

Second, a key contribution of this study is in tracing intervention mechanisms through students’ attitudes, behavioral indications of school engagement, and grades. The results advance the theory encapsulated in Fig. 1, highlighting the sequential importance of both a multifaceted psychological sense of belonging in middle school and behavioral engagement. In particular, our findings indicate that fostering trust and positive relationships between middle school students and their teachers appears especially important for promoting students’ academic and behavioral outcomes. Connections to key institutional agents are hypothesized to reinforce lasting psychological change and create recursive benefits of our brief intervention. Future research should build on this evidence by exploring how teachers’ actions sustain or subvert specific belonging intervention impacts in middle school.

A third important implication of our results is that they suggest widespread benefits of the belonging intervention in middle school. We did not find definitive evidence in support of the hypothesis of greater benefits for more socially marginalized groups. This may reflect nearly universal benefits of promoting belonging during middles school because it is a period of widespread developmental and environmental belonging challenges, compared with particular postsecondary settings where belonging worries may be most acute for particular groups (6, 18, 19). That said, our estimates cannot rule out larger benefits for historically underserved minority and male students, and future research is needed to assess these patterns independently in other settings. We note that the present school district was relatively well resourced, and despite some of the largest racial achievement gaps in the nation, we observed negligible demographic differences in belonging measures before the intervention; both factors may contribute to relatively wide and uniform benefits of increased school belonging.

Layered upon these 3 key implications is the novelty of scale in this study—a study of this approach across an entire public school district—which provides unique insight about policy relevance. The reappraisal intervention was effective at scale, and if a school district were to adopt the interventions for administration, the cost for doing so would be extremely low. Specifically, replication would require the printing costs for the exercises and, potentially, the opportunity costs of allocating teachers’ time to administering the exercises rather than to some other classroom activity. Our estimate of the cost of implementing this intervention suggests the typical school system could sustain delivery of the intervention’s 2 exercises at a cost of approximately $1.35 per student per academic year (see SI Appendix for details). This compares quite favorably to the typical costs of other social–emotional learning interventions reviewed by Belfield and colleagues (23), who found average costs of $581 per student across the 6 interventions that they reviewed.

Finally, though these outcomes highlight the practical importance of this intervention for reappraising middle school adversity, they also call attention to the more prominent issue of addressing the social–psychological needs of middle school students more generally. Given the significant personal, social, and economic consequences of dropping out of school, greater attention should be directed toward preventing the process of disengagement, which often takes root at the start of middle school. Indeed, poor attendance, misbehavior, and declining grades in sixth grade are early warning flags, which more often than not predict students’ dropping out of high school (24). With timely and credible reassurances of middle school students’ belongingness, the intervention tested here can be useful for schools as an additional tool in their larger overall tool kit to help students succeed through the difficult transition to middle school.

Materials and Methods

Intervention.

The belonging materials were based on social–psychological theory (4) and designed by Goyer and colleagues (25), building on previous intervention research on reappraisal and social belonging (4, 13, 26). Small modifications for the local context were made with feedback from preliminary surveys and focus groups conducted with prior sixth graders in the participating school district. The final exercises (SI Appendix) featured quotations and stories ostensibly from a “survey” of the prior year’s sixth-grade students about their experiences. These accounts were designed to align with students’ sentiments in focus groups but were written by researchers to highlight the core messages of the intervention. These messages included 1) reassurance that nearly all students at their school feel they struggle to fit in and feel capable of succeeding in school at first but, over time, come to realize they do belong, 2) advice on and examples of ways to engage in the school’s social and academic environment, and 3) confirmation that other students and teachers are there to help and support them. The first exercise focused on concerns about belonging due to academics, while the second focused on concerns about interpersonal relationships with adults and peers. In both cases, to promote internalizing these messages, students were then asked to reflect in writing on the information they read, considering how they could address their own difficulties and how those difficulties will become easier to manage over time. Ultimately, the intervention was meant to provide reassurance and advice from their peer group that difficulties occur for everyone entering middle school (not just particular students or groups) and suggest that they, too, will overcome these difficulties.

Study Implementation.

Using procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin, students were recruited to participate in the study (including student assent and parental consent) in August and September. Participating students were block randomized within the 11 schools in the district to the intervention or a control condition with identical cover sheets; nonparticipating students were provided alternate but similar individual activities during the same time. The 2 administrations were conducted early in the year (September and last week of October or first week in November). The exercises were administered by regular teachers during appropriate class time (39% in homeroom and 61% in English language arts classes). Teachers received training and instructions for distributing the materials and returned completed activities to researchers. Teachers were asked to administer the exercise as a normal reflective or free-writing activity and to refrain from describing it as research or an assessment. Throughout all phases of implementation, students, parents, and teachers were not informed of the specific study hypotheses (the study was described generally as an effort to learn about middle school students’ opinions) and were blind to experimental condition.

Surveys were administered separately from the writing exercises by research staff to all sixth-grade students in September 1 to 2 wk before the first exercise and in May at the end of the school year.

Data.

Data were compiled from district administrative records and student surveys administered at the beginning and end of the school year. Among participants randomized to condition, 9% of observations were removed due to missing outcome data, not differential by condition (χ2 = 0.14, degrees of freedom = 1, P = 0.71). The resulting sample consists of 1,304 participants for whom data from both fifth and sixth grades were available, representing 73% of the district’s total sixth-grade enrollment. Consistent with prior theoretical interpretations and empirical results (21), we also identified students from historically underserved groups (African American, Latino, Native American, and multiracial, 44% of the sample) as most at risk for belonging challenges and low academic achievement.

Student survey measures.

The student survey assessed the social and emotional well-being of participants in terms of attitudes related to aspects of school experiences (school trust, social belonging, evaluation anxiety, identification with school; ref. 27). All survey items use a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). School trust measured the degree to which students believe that adults in the school care about them and treat them fairly (α = 0.74; e.g., “The teachers at this school treat students fairly”). Social belonging assessed a student’s fit within school (α = 0.78; e.g., “I feel like I belong in my school”). Evaluation anxiety measured the negative thoughts students might have about evaluation in school (α = 0.80; e.g., “If I don’t do well on important tests, others may question my ability”). Identification with school captured the degree to which a person places importance on doing well at an activity (α = 0.78; e.g., “I want to do well in school”).

School records.

Students’ grades, behavioral referrals, and absences were coded from their official school records. For academic outcomes (GPA, number of Ds and Fs) we used cumulative records from terms 2 to 4 of the study year, which represent grades received after implementing the intervention exercises. For behavior outcomes, we similarly only included incidents that occurred after the implementation of the intervention exercises.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Walton and Geoffrey Cohen for sharing their belonging intervention materials with us and for advice during the design of this project and Dominique Bradley, Evan Crawford, Rachel Feldman, Adam Gamoran, Jeffrey Grigg, Erin Quast, Jackie Roessler, and Alex Schmidt for assistance during the project. Research reported here was supported by grants from the US Department of Education (R305A110136) and the Spencer Foundation (201500044). The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of supporting agencies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1820317116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Yeager D. S., Dahl R. E., Dweck C. S., Why interventions to influence adolescent behavior often fail but could succeed. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 101–122 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eccles J. S., et al. , Development during adolescence. The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. Am. Psychol. 48, 90–101 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blakemore S. J., Mills K. L., Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 65, 187–207 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walton G. M., Brady S. T., “The many questions of belonging” in Handbook of Competence and Motivation: Theory and Application, Elliot A. J., Dweck C. S., Yeager D. S., Eds. (Guilford Press, New York, NY, ed. 2, 2017), pp. 272–293. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumeister R. F., Leary M. R., The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walton G. M., Cohen G. L., A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 82–96 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwerdt G., West M. R., The impact of alternative grade configurations on student outcomes through middle and high school. J. Public Econ. 97, 308–326 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eccles J. S., et al. , Negative effects of traditional middle schools on students’ motivation. Elem. Sch. J. 93, 553–574 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wentzel K. R., Student motivation in middle school: The role of perceived pedagogical caring. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 411–419 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okonofua J. A., Walton G. M., Eberhardt J. L., A vicious cycle: A social–psychological account of extreme racial disparities in school discipline. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11, 381–398 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredricks J. A., Eccles J. S., Children’s competence and value beliefs from childhood through adolescence: Growth trajectories in two male-sex-typed domains. Dev. Psychol. 38, 519–533 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy M. C., Steele C. M., Gross J. J., Signaling threat: How situational cues affect women in math, science, and engineering settings. Psychol. Sci. 18, 879–885 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walton G. M., Cohen G. L., A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science 331, 1447–1451 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beilock S. L., Schaeffer M. W., Rozek C. S., “Understanding and addressing performance anxiety” in Handbook of Competence and Motivation: Theory and Application, Elliot A. J., Dweck C. S., Yeager D. S., Eds. (Guilford Press, New York, NY, ed. 2, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson T. D., Linville P. W., Improving the performance of college freshmen with attributional techniques. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 49, 287–293 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeager D. S., et al. , Teaching a lay theory before college narrows achievement gaps at scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E3341–E3348 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen G. L., Garcia J., Purdie-Vaughns V., Apfel N., Brzustoski P., Recursive processes in self-affirmation: Intervening to close the minority achievement gap. Science 324, 400–403 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broda M., et al. , Reducing inequality in academic success for incoming college students: A randomized trial of growth mindset and belonging interventions. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 11, 1–22 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walton G. M., Logel C., Peach J. M., Spencer S. J., Zanna M. P., Two brief interventions to mitigate a “chilly climate” transform women’s experience, relationships, and achievement in engineering. J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 468–485 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephens N. M., Fryberg S. A., Markus H. R., Johnson C. S., Covarrubias R., Unseen disadvantage: How American universities’ focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 1178–1197 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer S. J., Logel C., Davies P. G., Stereotype threat. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 415–437 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai K., Keele L., Tingley D., Yamamoto T., Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 105, 765–789 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belfield C., et al. , The economic value of social and emotional learning. J. Benefit Cost Anal. 6, 508–544 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balfanz R., Herzog L., Mac Iver D. J., Preventing student disengagement and keeping students on the graduation path in urban middle-grades schools: Early identification and effective interventions. Educ. Psychol. 42, 223–235 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyer J. P., et al. , Targeted identity-safety interventions cause lasting reductions in discipline citations among negatively stereotyped boys. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 10.1037/pspa0000152 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs S. E., Gross J. J., “Emotion regulation in education: Conceptual foundations, current applications, and future directions” in International Handbook of Emotions in Education, Pekrun R., Linnerbrink-Garcia L., Eds. (Educational Psychology Handbook Series, Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, New York, NY, 2014), pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pyne J., Rozek C. S., Borman G. D., Assessing malleable social-psychological academic attitudes in early adolescence. J. Sch. Psychol. 71, 57–71 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.