Abstract

Patient: Male, 47

Final Diagnosis: Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

Symptoms: Spastic paresis

Medication: Methylprednisolone

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: General and Internel Medicine

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a demyelinating disease that usually presents in pediatric patients, usually following a viral or bacterial infection. The clinical findings in ADEM include acute neurologic decline that typically presents with encephalopathy, with some cases progressing to multiple sclerosis. An atypical case of ADEM is reported that presented in a middle-aged adult.

Case Report:

A 46-year-old Caucasian man, who had recently emigrated to the US from Ukraine, presented with gait abnormalities that began four days after he developed abdominal cramps. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with contrast, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and T2-weighting showed contrast-enhancing, patchy, diffuse lesions in both cerebral hemispheres. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was negative for oligoclonal bands. On hospital admission, the patient was treated with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone, 500 mg twice daily. He responded well and was discharged from hospital after a week, with resolution of his presenting symptoms and signs.

Conclusions:

This report is of an atypical presentation of ADEM in a middle-aged patient who presented with spastic paresis. Although there are no set guidelines for the diagnosis of ADEM in adults, this diagnosis should be considered in patients with acute onset of demyelinating lesions in cerebral MRI. As this case has shown, first-line treatment is with high-dose steroids, which can be rapidly effective.

MeSH Keywords: Demyelinating Autoimmune Diseases, CNS; Encephalomyelitis, Acute Disseminated; Gait Ataxia; Multiple Sclerosis

Background

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a demyelinating disease that presents with acute inflammation and demyelination of the central nervous system (CNS) in a monophasic manner. ADEM is more commonly a disease of childhood that often follows viral infections, bacterial infections, or vaccinations [1,2]. The clinical characteristics include focal neurologic deficits, accompanied by encephalopathy, that develop one to three weeks after viral infection [1,2]. ADEM can be associated with rapid neurologic decline, but spastic paresis alone is rarely seen. ADEM is more commonly seen in children and young adults and rarely occurs in middle-aged or elderly adults. The course may be fulminant, but typically there is recovery in 50–75% of cases, with progression to multiple sclerosis (MS) in up to 20% of cases [1,2]. An atypical case of ADEM is reported that presented in a middle-aged adult.

Case Report

A 46-year-old, previously healthy Ukrainian man presented to the emergency department complaining of diffuse abdominal cramping pain four days prior to admission and bilateral lower extremity weakness and spastic gait, which occurred two days after the onset of abdominal pain. He denied fever, chills, diaphoresis, altered mental status, headache, seizures, vertigo, paresthesia, amaurosis fugax, tinnitus, otalgia, or facial paralysis. He reported that a month before admission, he had an episode of dysarthria that lasted for three days, but this resolved without medical management.

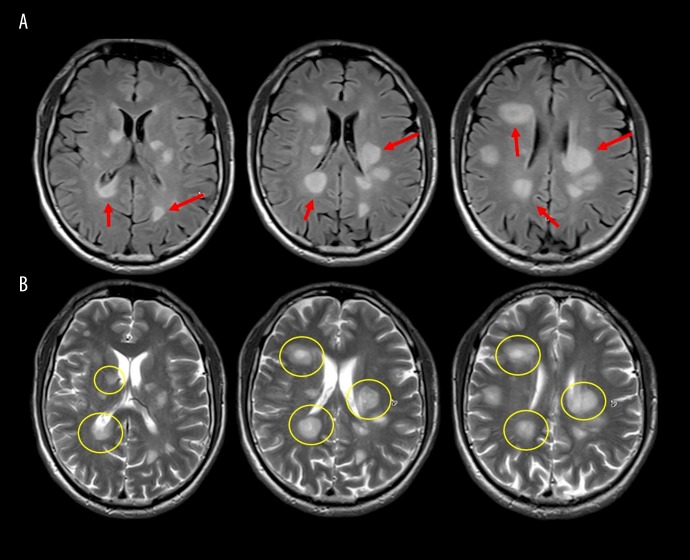

On physical examination, he had sustained clonus of the right and left ankles, increased lower extremity muscle tone, and spastic gait. There were no cranial nerve abnormalities, no meningeal signs, no cranial nerve deficits, and no sensory deficits were found. Initial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast enhancement showed multiple T2-weighted, contrast-enhancing, diffuse patchy lesions in both cerebral hemispheres that occupied part of the basal ganglia, which explained the presenting symptoms (Figure 1). There were no intracranial masses and MRI of the spine was normal.

Figure 1.

Pre-treatment brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast. (A) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows multiple round lesion, seen as an increased signal (arrow). (B) T2-weighted MRI images represent the lesions with a central enhancing portion (circle).

Lumbar puncture was performed, which showed an opening pressure of 7.5 cmH20 with no oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The findings of the examination of the CSF and serological screening for infection are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The patient was admitted to the medical ward where the findings from testing using an autoimmune disease test panel were found to be negative (Table 3).

Table 1.

CSF studies.

| CSF Studies | Results | Normal values |

|---|---|---|

| Color | Colorless | Colorless |

| Appearance | Clear | Clear |

| White blood cell count | 6 cell/mcL | ≤5 cell/mcL |

| Red blood cell count | 40 cell/mcL | ≤2 cell/mcL |

| Segmented cell | 14% | 23–31% |

| Lymphocytes | 72% | 40–80% |

| Monocytes | 14% | 25–46% |

| Glucose | 84 mg/dL | 40–70 mg/dL |

| Protein | 38.9 mg/dL | 15–45 mg/dL |

| IGG | 4.1 mg/dL | 0.0–6.0 mg/dL |

| Albumin | 24 mg/dL | 0–35 mg/dL |

| Albumin index | 5.6 ratio | 0.0–9.0 ratio |

| IGG/albumin ratio | 0.17 ratio | 0.09–0.25 ratio |

| CSF oligoclonal bands | 0 | 0 |

| Toxoplasma gondii PCR | <0.90 | <0.90 |

| Cultures [bacterial/AFB/mycotic] | Negative | Negative |

Source: Patient clinical chart.

Table 2.

Micro-bacteriology panel in CSF.

| Study | Results | Normal values |

|---|---|---|

| Cryptococcus antigen | Negative | Negative |

| Histoplasma antigen | Negative | Negative |

| Toxoplasma gondii IgG/IgM | 20.2/<3.0 IU/mL | <3.0/<3.0 IU/mL |

| Toxoplasma gondii PCR | Negative | Negative |

| Quantiferon – TB Gold | Negative | Negative |

| HIV 1/2 Screen | Negative | Negative |

Source: Patient clinical chart.

Table 3.

Autoimmune panel.

| Study | Results | Normal values |

|---|---|---|

| ACE Levels | 26 Unit/L | 9–67 Unit/L |

| CH-50 | 84 mg/dL | 60–144 mg/dL |

| C3 | 114 mg/dL | 88/201 mg/dL |

| C4 | 15 mg/dL | 10–40 mg/dL |

Source: Patient clinical chart.

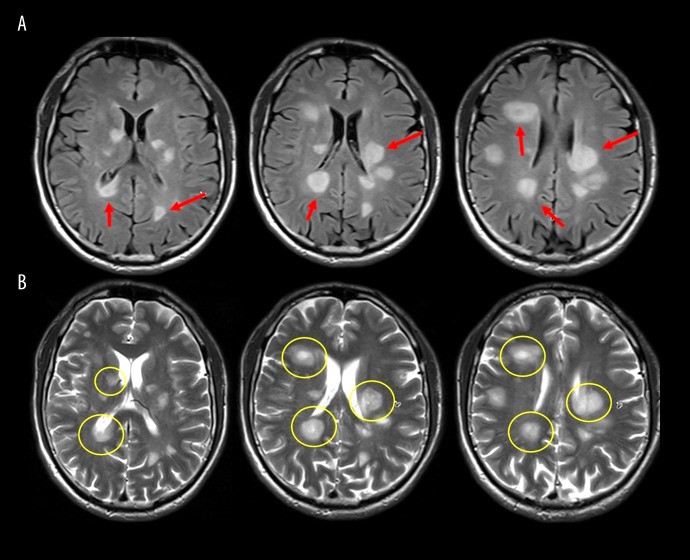

The patient began treatment with methylprednisolone 500 mg intravenously (IV) twice daily, which continued for a total of five days followed by complete resolution of the bilateral clonus and improvement of his spastic gait. Repeat brain MRI on the fifth day of steroid therapy showed improvement of the patchy cerebral lesions with no contrast-enhancement (Figure 2). The patient was discharged home for outpatient follow-up, but he returned to Ukraine two weeks after discharge.

Figure 2.

Post-treatment brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast. (A) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows multiple round lesions seen as an increased signal with slight improvement after steroid treatment (arrow). (B) T2-weighted MRI images represent the lesions with the enhancing portion being central in most of them, with a slight improvement after treatment (circle).

Discussion

This report is of a case of a middle-aged adult man who presented with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) that followed symptoms of diffuse abdominal cramping pain. It was not determined whether or not the patient had a previous episode of viral gastroenteritis. ADEM is more commonly a condition that presents in childhood, and the diagnosis in adults and the elderly remains challenging, as there are no established diagnostic criteria [1].

Pediatric clinical guidelines indicate that for the diagnosis of ADEM, the presence of encephalopathy is mandatory, but since due to the lack of diagnostic guidelines for adults, encephalopathy is an unclear diagnostic feature in this age group [2,3]. Other presenting clinical features for ADEM include hemiparesis, cranial nerve palsies, paraparesis, meningism, ataxia, movement disorders, and in some extreme cases, seizures can occur, but a presentation with predominantly spastic paresis is uncommon [4].

The diagnosis of ADEM is made clinically, and distinguishing ADEM from multiple sclerosis (MS) remains challenging due to the overlap in the clinical presentation of the two diseases. The findings from brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful in the diagnosis, as on imaging, the brain lesions in MS are better demarcated when compared with the indistinct lesions found in ADEM. Also, in T1-weighted brain MRI, findings that include the black holes sign are more suggestive of the diagnosis of MS. Brain MRI in ADEM shows patchy increased signal intensity on conventional T2-weighted imaging and on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI. In ADEM, the white matter is more frequently involved, but the grey matter can still be affected and lesions can be seen in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem, resulting in symptoms that are similar to those found in the present case. The 2017 revision of the McDonald Criteria for the diagnosis of MS has provided useful criteria that might help to distinguish between MS and ADEM [5]. The diagnosis of MS requires clinical or imaging support for the dissemination of lesions of the CNS in time and space [5], while ADEM remains chiefly monophasic and self-limiting [4,6–8].

Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in patients with ADEM is usually normal, but some patients may have an increased opening pressure, lymphocytic pleocytosis, but with normal CSF glucose. Oligoclonal bands in the CSF may also be found in patients with ADEM, but they are more commonly seen in patients with MS patients [9,10]. Treatment with methylprednisolone and supportive management remain the mainstay of treatment for ADEM, but immunomodulation and plasmapheresis have been used successfully in some refractory cases. More than half of cases recover completely after treatment [11,12].

Conclusions

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a demyelinating disease that occurs more commonly in children. ADEM that presents in adults can be challenging to diagnosis and to distinguish from multiple sclerosis (MS) or other demyelinating diseases. The clinical history and examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and the findings from examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) should be evaluated in patients with suspected ADEM. Also, a history of prodromal viral infection, bacterial infection, or Rickettsial infection, and recent vaccinations have all been documented as triggers of the onset of ADEM. Although the most common symptom on presentation is encephalopathy, less common presentations of ADEM, as in the present case, also include spastic paresis. The MRI findings in ADEM typically include patchy lesions in the grey matter with indistinct margins and some central contrast enhancement. It is important to make the diagnosis of ADEM and to commence treatment as rapidly as possible because, as this case has shown, complete recovery can occur.

References:

- 1.Mahdi N, Abdelmalik PA, Curtis M, et al. A case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in a middle-aged adult. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:601706. doi: 10.1155/2015/601706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaunzer UW, Salamon E, Pentsova E, et al. An acute disseminated encephalomyelitis-like illness in the elderly: Neuroimaging and neuropathy findings. J Neuroimaging. 2017;27:306–11. doi: 10.1111/jon.12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alper G. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. J Child Neurol. 2012;27(11):1408–25. doi: 10.1177/0883073812455104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg RK. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79(927):7–11. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.927.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:162–73. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Porcel F, Hornik A, Rosenblum J, et al. Refractory fulminant acute disseminated enecephalomyelitis (ADEM) in an adult. Front Neurol. 2014;23(5):270. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noorbakhsh F, Johnson RT, Emery D, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: Clinical and pathogenesis features. Neurol Clin. 2008;26(3):759–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruz OG, Donaire A, Berlioz AR, et al. Multiple sclerosis: A review; The challenge in Honduras. Rev Med Hondur. 2015;83(2):66–73. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karussis D. The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and the various related demyelinating syndromes: A critical review. J Autoimmun. 2014;48:134–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang HQ, Zhao WC, Feng SM, et al. An adult case of multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis manifesting with optic neuritis. Intern Med. 2014;53(9):1005–11. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu A, Shan R, Huang D, et al. Case report: Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis following viper bite. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(4):e3510. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viswanathan S, Botross N, Rusli BN, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis complicating dengue infection with neuroimaging mimicking multiple sclerosis: A report of two cases. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;10:112–15. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]