Abstract

Background

The effect of foot orthoses in terms of kinematics and kinetics during walking could be affected on different geometrical designs. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the biomechanical and clinical effects of 3 different insoles on rearfoot motion (RFM) and ankle joint moment parameters.

Material/Methods

Twenty eight university students with flexible flatfoot were recruited for this study, and each participant was asked to wear 3 different insoles: normal insole without arch support function, type A insole with only arch support function, and type B insole with both arch support and cushion pads for shock absorbing functions. Three-dimensional motion analysis was performed to compute the ranges and peak orientation angles of RFM and ankle joint moment parameters.

Results

The type A and type B insoles exhibited significantly smaller peak everted position and evertor moment than the normal insole. Also, the type A insole showed significantly smaller range of rearfoot motion in the longitudinal axis and the length of MA (moment arm) in the mediolateral axis than the normal insole.

Conclusions

The use of the type A insole using arch support function was induced to promote a cautious gait pattern associated with a relatively lower potential risk compared to the normal insole. The type A and type B insoles could be important to positively reduce the possibility of injury. Also, the smaller length of MA in the type A insole might have a contribution to the decrease of ankle joint evertor moment.

MeSH Keywords: Ankle Joint, Biomechanical Phenomena, Flatfoot, Foot Orthoses

Background

Flatfoot is a congenital or acquired disease affecting about 23% of the world population and refers to an abnormally low or collapsed medial arch, which alters typical gait patterns [1]. Depending on the flexibility of the medial arch, a diagnosis of flatfeet can be subdivided into flexible or rigid categories [2]. Of the sub classifications, flexible flatfoot predominates and is characterized by the appearance of the flatfeet only during weight bearing activities such as walking or standing [3]. The gait motion of patients with flatfeet are characterized by medial rotation of the talus due to eversion of the calcaneus, and pronation and abduction of the forefoot [4,5]. As a result, patients with flexible flatfeet could have a deterioration in the function of the normal foot. Flatfoot during adulthood can be progressive in the absence of appropriate intervention, eventually cascading into a fixed supination deformity [6,7]. The soft tissues (muscles, tendons, bones, and ligaments) that help maintain normal foot arches are strengthened to form arches at about 16 years old [8]. For these reasons, patients 16 or older with flexible flatfeet should seek to improve their condition as soon as possible.

Patients diagnosed with flexible flatfoot are often treated with an orthosis used as a non-surgical and clinical intervention. The orthosis is an insole which supports the medial arch of the foot. The basic principle is that the collapsed arch is shaped into a normal foot arch by the arch supported insole [9]. The wedged insole can be inserted into the shoe to induce the vertical alignment of the lower extremity [10]. Postural improvement through vertical alignment corrects for excessive medial deviation of the center of pressure (COP), resulting in a decrease in moment arm (MA) in the ankle joint [11–13]. When selecting an arch-supported orthosis, it is necessary to know the sub-classification of flatfoot (flexible or rigid). In the case of flexible flatfoot, the subtalar joint can become neutral and loads placed on the posterior tibial tendon can be reduced. However, in the case of rigid flatfeet, an orthosis may cause pain by raising the pressure [7].

The potential factors related to injuries or pain development from flatfeet include acute stress, low joint instability, lack of strength and endurance, muscle fatigue, and stress due to long loading times [14]. Especially during walking, there is a high possibility that the evertor/invertor and adduction/abduction moments highly related to foot motion of the lower extremity could cause excessive injury or pain at the joints [15]. In a situation where the joints are directly subjected to a load, the joint moment is an indirect indication of the joint load [16–18]. The joint moment is determined by the combination of the ground reaction force (GRF) and the MA [17]. GRF has a special meaning because a person can intentionally control its magnitude, direction, and point of application. Also, the length of the MA can be controlled according to the point of application and the direction of the applied force. Furthermore, these 2 components could be controlled by foot orthoses. The magnitude of the joint moment during gait is very important in terms of efficiency and in regards to the amount of muscle activation and injury prevention [19]. Therefore, potential injury prevention strategies can be aimed at reducing GRF, MA, or a combination of both.

The human body can be viewed as a system of linked segments [20]. Motion of the ankle joint can impact other joints such as the knee and hip joints, as well the alignment of the entire lower extremity [21]. Walking is characterized as a closed kinetic-chain motion of the lower limb [22]. Therefore, foot motion has an effect on the movement and the loading of the lower limb joint [23]. Rearfoot motion (RFM) is an especially important element of gait mechanics because during normal gait it is the first body part that contacts the ground, in addition to transferring external forces from the ground to the lower limb [24]. RFM occurs between the talus and the calcaneus, and the eversion and inversion of the calcaneus are involved in the pronation and supination of the foot during walking [25]. The increase of the movement (the eversion and inversion of the RFM) and contact time of the foot provides a buffering effect of the external force and absorption of the force during collision with the ground [26]. However, excessive eversion and inversion motions can reduce the stability of the ankle, and these motions can also affect ankle joint moments [27]. One of the most controversial aspects of the recent studies has been whether the limited motions of RFM are more effective to reduce potential injury risk.

To date, despite these unclear results from previous researches, most biomechanical studies using orthoses during walking have focused on assessing the moments of the knee joint and the hip joint [28–30], and the function of the lateral wedge insole [28,31–33]. As a consequence, there is still a lack of research on RFM and ankle joint moment parameters (MA and GRF) in patients with flexible flatfeet. The analysis of ankle motion mechanics, specifically RFM, and ankle joint moment parameters related to gait could contribute to understanding the potential mechanisms for injury. The effect of foot orthoses in terms of kinematics and kinetics during walking could be affected on different geometrical designs [34]. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the biomechanical and clinical effects of the normal insole without arch support function, the type A insole with only arch support function, and the type B insole with both arch support and cushion pad on rearfoot for a shock absorbing function on the RFM and ankle joint moment parameters.

Material and Methods

Participants

A total of 28 university students with flexible flatfoot were recruited for this study (mass=70.43±4.15 kg; height=175.14±3.55 cm; age=20.29±0.46 years). The sample size was computed using G*Power 3.1 software (effect size d=0.25; significant level α=0.05; power=0.80). In order to compute arch height index (AHI), dorsal height (at 50% of total foot length) was divided by truncated foot length (length from heel to first metatarsal joint). From that, the ratio was defined as AHI. AHI was obtained in standing posture with even weight distribution on both feet by using 2 force plates. The criteria for patients with the flexible flatfoot was limited to participants who have over 10 mm in navicular drop [35] and below 0.31 in AHI [36]. All participants were right foot dominant. All participants were limited to male students so as to remove gender differences as a factor, and participants who were suffering from any major injuries that might prevent walking were excluded. The human participant research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Silla University and the purpose and procedures of the study were explained to the participants prior to data collection.

Trial condition

Participants were asked to perform 5 trials with their own shoes. In order to perform the data collection, each participant was asked to wear 3 different insoles (the normal insole was used as an experimental control for this study and without arch support function, the type A insole with only arch support function, and the type B insole with both arch support and cushion pads for shock absorbing functions) (Figure 1). The hardness and foot arch descent of the type A and the type B insoles were 45º and 94%, respectively. Prior to data collection, a metronome set at 80 beats per minute was used to control for walking speed. Sufficient practice was given to allow participants to adjust to the set pace. To keep participants from fixing their eyes to their feet (abnormal gait pattern) a target was located approximately 15 degrees above eye level.

Figure 1.

Three types of insoles.

Data collection

In order to capture the motion trajectories, a 250-Hz 10-camera VICON motion capture system (Centennial, CO, USA) was used. A total of 21 reflective markers were attached on the participant’s body: 9 on each leg (lateral thigh, medial and lateral epicondyles of the knee, lateral shank, medial and lateral malleoli of the ankle, tip of middle toe, and heel) and 3 on the pelvis (sacrum, right and left anterior superior iliac spines). The camera calibration was performed before data collection, during which the global X-axis (laboratory reference frame) was aligned with the forward direction the participants facing at the starting position and the vertical axis (upward) was set as the global Z-axis. The global Y-axis, therefore, was the right to left direction. Two AMTI force plates (Model OR6; Advanced Mechanical Technology, Inc., Watertowwn, MA, USA) were used to measure the ground reaction force data. Data sampling rate of the force plate was set at 1000 Hz.

Data reduction and processing

Kwon3D Motion Analysis Suite (Version XP; Visol, Seoul, Korea) was used to process and analyze data. The point coordinates were digitally filtered using a Butterworth 4th-order zero phase lag low-pass filter. The cutoff frequency was set to 6 Hz. De Leva’s body segment parameters (ratios) [37] was used in locating the COM of the segments. Segmental reference frames for the lower extremities (pelvis, foot, shank, and thigh) were defined according to methods described by [38]. For this method, the X-axes were aligned with the mediolateral axes of the segments, the Y-axes were along the anteroposterior axes, and the Z-axes were aligned with longitudinal axes. The relative orientation angles (Cardan angles) of the rearfoot to respective shanks were computed using the XYZ rotation sequence. A unique feature to the Kwon3D Motion Analysis Suite is that the foot is defined as if the person was standing on their toes. Therefore, the Z axis of the rearfoot in this study was used to compute the inversion/eversion angles.

Data analysis

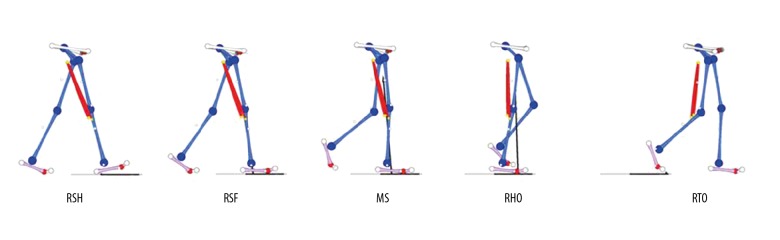

Five events were identified for data analysis (Figure 2): right heel strike (RHS) – the instant at which the heel strikes the ground, right sole flat (RSF) – the instant at which the sole touches ground completely, mid stance (MS) – the instant at which left toe lifts off the ground, right heel off (RHO) – the instant at which the right heel lifts off the ground, and right toe off (RTO) – the instant at which the right toe lifts off the ground. Since the problem of flexible flatfoot during walking was caused only by contact with the ground at the stance phase, the events were taken by only the stance phase of the dominant side (right side) in the whole gait cycle.

Figure 2.

Five events during walking. RSH – right heel strike; RSF – right sole flat; MS – mid stance; RHO – right heel off; RTO – right toe off.

The orientation angle parameters of the rearfoot relative to its respective proximal segment (shank) and the ankle joint moment in the longitudinal axis were computed for the analysis. GRF and MA in the mediolateral axis were added to assess the ankle joint moment parameters. MA, in the mediolateral axis, was defined as the perpendicular distance from the ankle joint center to the line of action of GRF. GRF and MA values were derived from the instance at which normalized ankle joint moment (evertor) in the mediolateral axis was maximized. Additionally, the timings of GRF and MA were used for further analysis. The ensemble average patterns during walking were derived using the RHS-RTO phase normalized as 100% time. The ankle joint moments and GRF were normalized to participant’s body mass (BM), respectively, to eliminate the effect of body size.

Statistical analysis

The dependent variables used in the analysis were peak orientation angles (inversion/eversion positions) and ranges of the orientation angles of the right rearfoot, peak resultant joint moment (evertor and invertor) of the right foot, GRF, and MA. The average of the data of 5 trials in all data analysis were used for statistical analysis. A repeated measure one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was to compare the mean values of each dependent variable between 3 types of insoles. Post hoc tests were conducted using Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons if the factor effect is significant (P<0.05). The acceptance level of this study hypothesis was set to α=0.05 to verify the significance of the test. All statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS V.24.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Among the rearfoot motion variables, peak everted position of the rearfoot (F2, 81=5.928, P=0.004), range of rearfoot motion (F2, 81=5.257, P=0.007), and evertor moment (F2, 81=6.307, P=0.003) revealed significant (P<0.05) inter-insole differences during stance phase (Table 1). Among the ankle joint moment parameters, significant insole effect was observed in MA (F2, 81=4.671, P=0.012) during stance phase (Table 1). The Post Hoc tests showed that the type A and the type B insoles exhibited significantly smaller peak everted position (P<0.016. and P<0.008, respectively) and evertor moment (P<0.005 and P<0.017, respectively) than normal insole. Also, the type A insole showed significantly smaller range of rearfoot motion (P<0.008) in the longitudinal axis and MA in the mediolateral axis (P<0.018) than normal insole.

Table 1.

Peak timings (%) of ankle joint evertor moment, GRF and MA.

| Variable | Insole | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | A | B | |

| Peak joint moment | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| GRF | 75 | 76 | 74 |

| MA | 71 | 70 | 77 |

Event timings normalized as 100% time: RHS (1%), RSF (24%), MS (48%), RHO (69%), RTO (100%).

Discussion

This study was to compare the biomechanical and clinical effects of the normal insole, the type A insole with only arch support function, and the B type insole with both arch support and shock absorbing functions on the RFM and ankle joint moment parameters. Peak orientation angle and ranges of the rearfoot in the longitudinal axis and normalized resultant joint moment (RJM) of ankle in the longitudinal axis and GRF and MA in the mediolateral axis were calculated.

RFM

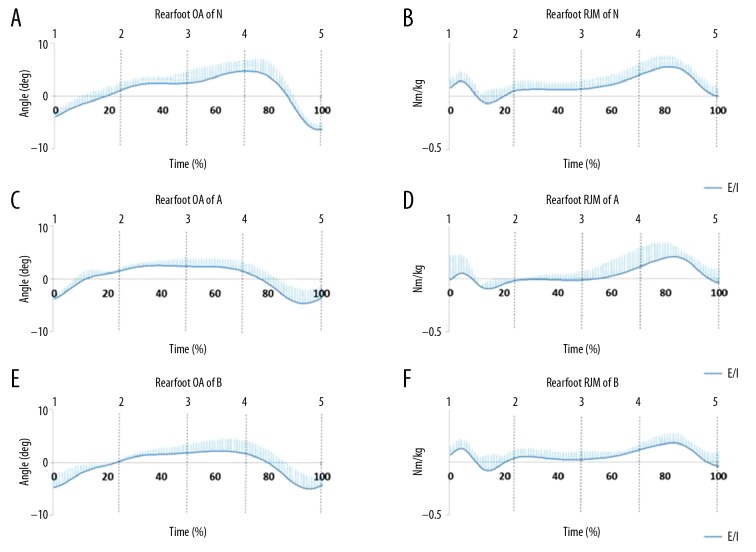

The ensemble average patterns of the orientation angles of RFM in the longitudinal axis were presented with 100% time normalization (Figure 3). RFM orientation angles in the type A and the type B insoles exhibited a transition from eversion to inversion right after MS (around 50% of normalized time) while the normal insole showed a transition from eversion to inversion motions after RHO (approximately 75% of normalized time) (see Figure 3). It could be considered that eversion motion in the normal insole occurred continuously after MS different from the type A insole and the type B insole. This could be due to the restricted movement along the longitudinal axis controlled by the type A insole and the type B insole, which was not present in the normal insole. The results from this study revealed that peak everted position values of RFM in the type A insole and type B insole (2.89±3.10° and 2.70±2.40°, respectively) in the longitudinal axis was significantly smaller than that of the normal insole (5.40±4.10°) (Table 2). This result was consistent with the findings of previous studies [39–42], which reported that the peak rearfoot eversion was significantly reduced with a medial forefoot and rearfoot posting insole inserted to the foot. Also, the forefoot adduction (1.6°) was made by the functional insole [43], resulting in a decrease forefoot pronation which could positively have an effect on the everted position of rearfoot in patients with flatfoot [44]. However, a study by Cobb et al. [40] reported that there was no significant effect on peak rearfoot everted position using the orthosis with arch support insole. It is speculated that a reason for this result could be due to a methodological limitation related to the shoe design used in each study (shoes were used in this and other aforementioned studies, whereas sandals were used in the Cobb et al. study [40]. Therefore, it might be premature to draw a distinct conclusion by comparing the Cobb et al. study [40] and our study. A significant difference was observed in the inversion/eversion range between the normal insole (11.40±5.03°) and the type A insole (7.59±4.15°). Although, no significant difference in the inversion/eversion range was found between the normal insole (11.40±5.03) and the type B insole (8.50±4.46°), substantial difference in the range (>2.9°) between these 2 insoles was revealed (Table 1). Additionally, no significant difference in the peak inverted position between the normal, the type A, and the type B insoles were found in this study (Table 1). It could be speculated that strict control of the type A and the type B insoles, due to arch support function in peak everted position, promoted less use in terms of RFM range of motion during stance phase. Positive changes in kinematic motions have previously been assumed to be associated with clinical improvements because it contributes to decrease muscle loading [45,46]. Therefore, the findings from this study suggested that changes in everted position and inversion/eversion range of RFM induced by the type A and the type B insoles using arch support function for injury prevention and treatment could cause a cautious gait pattern associated to potential risk of a relatively lower.

Figure 3.

Ensemble-average patterns of the orientation angles (A–C) and normalized ankle joint moment (D, E) in Z axis in 3 types of insoles (n=22): (A) normal, (B) type A, (C) type B, (D) normal (E) type A, and (F) type B. Event: 1 – RHS, 2 – RSF, 3 – MS, 4 – RHO, 5 – RTO. The RHS-RTO phase was used as 100% time. Relative positions: E – everted and I – inverted in left column, E – evertor and I – invertor in right column.

Table 2.

Comparison of RFM variables and ankle joint moment parameters (mean ±SD; N=28).

| Variable | Insole | F | P | Post-hoc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | A | B | ||||

| EP (º) | 5.40±4.10 | 2.89±3.10 | 2.70±2.40 | 5.928* | .004 | N>A, B |

| IP (º) | −6.00±4.10 | −4.70±3.20 | −5.70±4.20 | .869 | .423 | |

| ROM(º) | 11.40±5.03 | 7.59±4.15 | 8.50±4.56 | 5.257* | .007 | N>A |

| Evertor(Nm/kg) | 0.25±0.10 | 0.17±0.10 | 0.18±0.07 | 6.307* | .003 | N>A, B |

| Invertor(Nm/kg) | −0.07±0.10 | −0.05±0.10 | −0.05±0.04 | .505 | .605 | |

| GRF(N/kg) | 0.47±0.16 | 0.42±0.16 | 0.43±0.22 | .137 | .872 | |

| MA(cm) | 0.84±0.40 | 0.60±0.27 | 0.63±0.27 | 4.671* | .012 | N>A |

EP – everted position; IP – inverted position; GRF – ground reaction force; MA – moment arm. N – normal; A – type A; B – type B. RFM variables and the ankle joint moment in the longitudinal axis and GRF and MA in the mediolateral axis were computed.

p<.05.

There were no significant differences in all orientation angle parameters between the type A and the type B insoles (Table 1). The unique difference in terms of the geometrical design between the type A and the type B insoles was the presence of cushion pads (without pad for type A insole and with pad for type B insole) on the rearfoot. Based on the results in everted position and inversion/eversion range of RFM between the 2 insoles, it could be considered as no efficiency of cushion pads in the type B insole. One aspect that cannot be directly affect by the cushion pads would be as the everted/inverted position and inversion/eversion range values were derived from after RHO at which cushion pad was in the air.

Joint moment parameter (RJM, GRF, and MA)

The ankle joint moments in all types of insole were characterized by the initial evertor dominant phase followed by the invertor dominant phase before RSF, and then the continuous evertor dominant phase was observed in all the types of insoles (Figure 3). The timings of the peak invertor and evertor moments were revealed between RHS and RSF, and RHO and RTO, respectively, in all the types of insoles. The values of peak evertor moments in all the types of insoles were larger than that those of invertor moments.

The magnitude of the joint moment during walking could be considered a good indicator of injury prevention [19]. A biomechanical aspect directly affected by the arch support insoles is that the use of less evertor moment will positively reduce the possibility of injury by muscle fatigue and overuse [47]. The results from this study showed that normalized peak everted moment values of the ankle joint in the type A and the type B insoles (0.17±0.10 Nm/kg and 0.18±0.07 Nm/kg, respectively) in the longitudinal axis was significantly smaller than those of the normal insole (0.25±0.10 Nm/kg) (Table 2). One study [43] suggested that the use of foot orthoses would guarantee a lower rearfoot eversion moment. To our knowledge, only 1 study [48] has reported that there was no significant effect on the peak evertor moment of the ankle joint by applying an arch support insole to a patient with a flatfoot. One important methodological difference between that study [48] and our study was that the walking speed was self-selected, whereas the walking speed was controlled in this study). It is essentially important to set a walking speed which directly affects the amount of joint moments to get reliable results from all the conditions for a study.

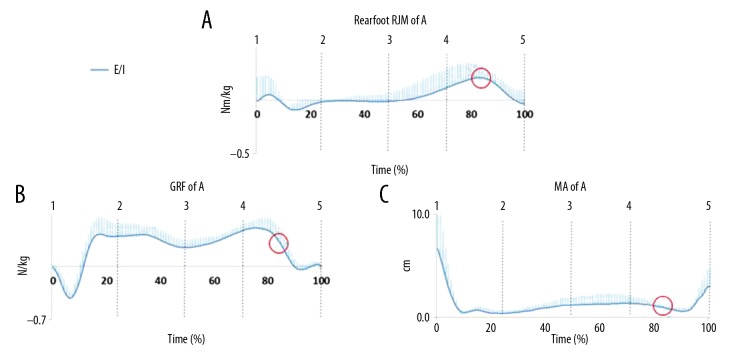

As mentioned previously, during stance phase in our study, the peak value occurred in the ankle joint in the longitudinal axis was the evertor moment between RHO and RTO at which patients pushed the ground to propulsion (Figure 3, Table 2). This is explained by a mechanism used in the foot-ground interaction in generating the peak evertor moment. This could be identified from the external moment components such as GRF and MA. The timings of peak ankle joint moments in the longitudinal axis were relatively consistent across all types of insoles while the timings of the maximum GRF and maximum MA were identified with different timings in all types of insoles at which the GRF and MA were not maximized (Table 1, Figure 4). This indicated that the generation of joint moment relied more on the combination of both MA and GRF magnitude, not peak GRF or MA. The results from our study revealed that a significant effect (P<0.05) was observed in ankle joint evertor moment and MA between insoles (Table 2). Especially, the length of MA in the type A insole was significantly smaller than that in the normal insole. It could be interpreted that the decrease of ankle joint evertor moment in the type A insole resulted from the smaller length of MA. Based on these results for ankle joint moment, GRF and MA, it could be suggested that patients with flatfoot relied on the effective arch support function from the type A insole to reduce the ankle joint moment.

Figure 4.

Exemplar GRF (B) and MA (C) timings at the instant (83%) of peak ankle joint evertor moment (A). E – evertor moment; I – invertor moment.

Limitations

In order to draw conclusions on the effect of foot orthoses for patients with flatfeet, the limitations from this study should be considered. First, this study did not include changes in muscle activity or plantar pressure that could verify the more corrective effectiveness of the insole. More in depth and widely research results are warranted to shed light on the potential risk factors for an injury mechanism. Second, the foot orthoses used in this study were not customized to each patient. It should be kept in mind that each patient responds differently to a new orthosis. Also, this study was conducted in only a limited walking circumstance. The radical motions such as running and cutting can lead to different patterns in RFM and joint moment parameters (e.g., GRF and MA) [49,50]. Therefore, experimental protocols for a future study would be needed in various situations to verify the effect of the insole with arch support function and cushion pad for a shock absorbing function.

Conclusions

First, the use of the type A insole, using arch support function, was induced to a less everted position and inversion/eversion range of RFM. It would promote a cautious gait pattern associated to potential risk of a relatively lower as compared to normal insole.

Second, the type A insole and type B insole showed a lower magnitude of ankle joint evertor moment. This could be important to positively reduce the possibility of injury.

Finally, the smaller length of MA in the type A insole might have a contribution to the decrease in ankle joint evertor moment.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Harris RI, Beath T. Hypermobile flat-foot with short tendo achillis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1948;30A:116–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haendlmayer KT, Harris NJ. (ii) Flatfoot deformity: An overview. Orthop Trauma. 2009;23(6):395–403. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deland JT, de Asla RJ, Sung IH, et al. Posterior tibial tendon insufficiency: Which ligaments are involved. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:427–35. doi: 10.1177/107110070502600601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arangio GA, Reinert KL, Salathe EP. A biomechanical model of the effect of subtalar arthroereisis on the adult flexible flat foot. Clin Biomech. 2004;19(8):847–52. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitaoka HB, Luo ZP, An KN. Three-dimensional analysis of flatfoot deformity: Cadaver study. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19(7):447–51. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SJ, Lee BG, Sung IH. Adult flatfoot. JKMA. 2014;57(3):243–52. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sung KS, Yu IS. Acquired adult flatfoot: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and nonoperative treatment. J Korean Foot Ankle Soc. 2014;18(3):87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cappello T, Song KM. Determining treatment of flatfeet in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1998;10:77–81. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199802000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marzano R. Nonoperative management of adult flatfoot deformities. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2014;31(3):337–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross MT. Lower quarter screening for skeletal malalignment – suggestions for orthotics and shoewear. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21(6):389–405. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.21.6.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crenshaw SJ, Pollo FE, Calton EF. Effects of lateral-wedged insoles on kinetics at the knee. J Clin Ortho Rel Res. 2000;375:185–92. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200006000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasuda K, Sasaki T. The mechanics of treatment of the osteoarthritic knee with a wedged insole. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1987;215:162–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kogler GF, Solomonidis SE, Paul JP. In vitro method for quantifying the effectiveness of the longitudinal arch support mechanism of a foot orthosis. Clin Biomech. 1995;10(5):245–52. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(95)99802-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toullec E. Adult flatfoot. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amin S, Luepongsak N, McGibbon CA, et al. Knee adduction moments and development of chronic knee pain in elders. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;5:371–76. doi: 10.1002/art.20396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prodromos CC, Andriacchi TP, Galante JO. A relationship between gait and clinical changes following high tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1188–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schipplein OD, Andriacchi TP. Interaction between active and passive knee stabilizers during level walking. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:113–19. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Kuo K, Andriacchi T, Galante J. The influence of walking mechanics and time on the results of proximal tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:905–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novacheck TF. The biomechanics of running. Gait Posture. 1998;7(1):77–95. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(97)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearsall DJ, Reid G. The study of human body segment parameters in biomechanics. Sports Med. 1994;18(2):126–40. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199418020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buck P, Morrey BF, Chao EY. The optimum position of arthrodesis of the ankle. A gait study of the knee and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(7):1052–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dugan SA, Bhat KP. Biomechanics and analysis of running gait. Phys Med Rehabil Clin. 2005;16(3):603–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eng JJ, Pierrynowski MR. The effect of soft foot orthotics on three-dimensional lower-limb kinematics during walking and running. Phys Ther. 1994;74(9):836–44. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.9.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oatis CA, Craik R. Gait analysis: Theory and application. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inman VT, Ralston HJ, Todd F. Human walking. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon YH, Hutcheson L, Casebolt JB, et al. The effects of railroad ballast surface and slope on rearfoot motion in walking. J Appl Biomech. 2012;28(4):457–65. doi: 10.1123/jab.28.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donovan L, Hertel J. A new paradigm for rehabilitation of patients with chronic ankle instability. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40(4):41–51. doi: 10.3810/psm.2012.11.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butler RJ, Marchesi S, Royer T, Davis IS. The effect of a subject-specific amount of lateral wedge on knee mechanics in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(9):1121–27. doi: 10.1002/jor.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin R, Menz HB. Use of laterally wedged custom foot orthoses to reduce pain associated with medial knee osteoarthritis: A preliminary investigation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005;95(4):347–52. doi: 10.7547/0950347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsung BYS, Zhang M, Mak AFT, Wong MWN. Effectiveness of insoles on plantar pressure redistribution. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2004;41(6):767–74. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2003.09.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang MA, Taylor CE, Nouvong A, et al. Effects of footwear on medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43(4):427–34. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2005.10.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giffin JR, Stanish WD, MacKinnon SN, MacLeod DA. Application of a lateral heel wedge as a nonsurgical treatment for varum gonarthrosis. J Prosthet Orthot. 1995;7(1):23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerrigan DC, Lelas JL, Goggins J, et al. Effectiveness of a lateral-wedge insole on knee varus torque in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(7):889–93. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banwell HA, Thewlis D, Mackintosh S. Adults with flexible pes planus and the approach to the prescription of customised foot orthoses in clinical practice: A clinical records audit. Foot. 2015;25(2):101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cote KP, Brunet ME, Gansneder BM, Shultz SJ. Effects of pronated and supinated foot postures on static and dynamic postural stability. J Athl Train. 2005;40(1):41–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butler RJ, Hillstrom H, Song J, et al. Arch height index measurement system: Establishment of reliability and normative values. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98(2):102–6. doi: 10.7547/0980102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeLeva P. Adjustments to Zatsiorsky-Seluyanov’s segment inertia parameters. J Biomech. 1996;29:1223–30. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwon YH, Como C, Singhal K, et al. Assessment of planarity of the golf swing based on the functional swing plane of the clubhead and motion planes of the body points in golf. Sport Biomech. 2012;11:127–48. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2012.660799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown GP, Donatelli R, Catlin PA, Wooden MJ. The effect of two types of foot orthoses on rearfoot mechanics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21(5):258–67. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.21.5.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cobb SC, Laurie LT, Jeffrey TJ, et al. Custom-molded foot-orthosis intervention and multi-segment medial foot kinematics during walking. J Athl Train. 2011;46(4):358–65. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johanson MA, Donatelli R, Wooden MJ, et al. Effects of three different posting methods on controlling abnormal subtalar pronation. Phys Ther. 1994;74(2):149–58. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nawoczenski DA, Ludewig PM. The effect of forefoot and arch posting orthotic designs on first metatarsophalangeal joint kinematics during gait. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(6):317–27. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2004.34.6.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Telfer S, Abbott M, Steultjens MP, Woodburn J. Dose-response effects of customised foot orthoses on lower limb kinematics and kinetics in pronated foot type. J Biomech. 2013;46(9):1489–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levinger P, Murley GS, Barton CJ, et al. A comparison of foot kinematics in people with normal-and flat-arched feet using the Oxford Foot Model. Gait Posture. 2010;32(4):519–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Genova JM, Gross MT. Effect of foot orthotics on calcaneal eversion during standing and treadmill walking for subjects with abnormal pronation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(11):664–75. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2000.30.11.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neville C, Flemister AS, Houck J. Effects of the AirLift PTTD brace on foot kinematics in subjects with stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(3):201–9. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McClay ID, Baitch SP. Effect of inverted orthoses on lower-extremity mechanics in runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(12):2060–68. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000098988.17182.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hurd WJ, Kavros SJ, Kaufman KR. Comparative biomechanical effectiveness of over-the-counter devices for individuals with a flexible flatfoot secondary to forefoot varus. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20(6):428–35. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181fb539f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hreljac A, Marshall RN, Hume PA. Evaluation of lower extremity overuse injury potential in runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9):1635–41. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Messier SP, Pittala KA. Etiologic factors associated with selected running injuries. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;20(5):501–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]