Abstract

Purpose

Korean-American mental health is poorly understood, and screening for sleep disturbances may be an effective means of identifying at-risk individuals.

Design

In partnership with a Korean-American church in Los Angeles, an online survey was administered.

Setting

The study was conducted at a Korean-American church in Los Angeles, California.

Subjects

The sample consisted of 137 Korean-Americans drawn from the church congregation.

Measures

Sleep disturbances were measured using a single ordinal variable, and mental health outcomes included nonspecific psychological distress, perceived stress, loneliness, suicidal ideation, hazardous drinking, treatment seeking behaviors, and perceived need for help.

Analysis

Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the associations between sleep disturbances and mental health outcomes, adjusting for age and sex. Results are presented as Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals.

Results

Almost a third of the sample reported moderate or severe sleep disturbances. After adjusting for age and sex, sleep disturbances were associated with greater odds of reporting probable mental illness, perceived need for treatment, and treatment-seeking behaviors. Sleep disturbances were also associated with higher levels of perceived stress and loneliness, but were not significantly associated with suicidal ideation or hazardous drinking.

Conclusions

Sleep disturbances are associated with mental health problems and may be an important idiom of distress for Korean-Americans. Primary care providers and informal providers in the community (specifically churches) should work together to screen for sleep problems and refer at-risk individuals to appropriate levels of care.

Keywords: Korean-Americans, sleep disturbances, mental health, churches, screenings

INTRODUCTION

There are currently more than 1.7 million Korean-Americans in the United States, and this population continues to grow annually. However, in the absence of nuanced research on Korean-American mental health, psychiatric providers have struggled to offer culturally responsive care to this population. It is thus no surprise that Korean-Americans tend to delay service utilization until symptoms become severe (Shin, 2002), or express psychological distress in culture-specific ways that are overlooked by providers (Kim, 1995; Park & Bernstein, 2008). Overall, Korean-Americans appear to underutilize formal psychiatric services, and so efforts must be made toward closing the treatment gap. Toward this end, professional providers can be trained to understand and respond to Korean-American expressions of psychological distress. At the same time, community-driven outreach must engage at-risk Korean-Americans in order to connect them to appropriate levels of care. In this report, we argue that screening for sleep disturbances may be a critical component of these efforts.

Studies have shown that sleep is essential to functioning, and that without it, people often face impairments in memory, emotion, cognition, and motor skills (Banks & Dinges, 2007). Sleep disturbance is also related to several psychiatric disorders (Benca, Obermeyer, Thisted, & Gillin, 1992). In the same way that Asian-Americans complain of physical symptoms to communicate distress (Pang & Lee, 1994), complaining of sleep disturbances could potentially serve the same purpose. If this is the case, then screening for sleep disturbances may be crucial in detecting mental health problems in the Korean-American community.

In this exploratory study, we partnered with a Korean-American church in Los Angeles and conducted a pilot study to test the feasibility of administering church-based sleep screenings. We describe the mental health correlates of sleep problems, hypothesizing sleep disturbances would be associated with a host of mental health problems. We then discuss the implications of these findings for mental health services and health promotion efforts.

METHODS

Design and Sample

Since an estimated 70% of Korean-Americans identify as Christian and attend worship services in some capacity (Social & Trends, 2012), the church may be an effective venue through which online screenings can be administered. We partnered with a Korean-American church (predominantly second-generation), selected based on the author’s personal connections. The authors and church leaders dialogued about the mental health needs of the congregation, and collaboratively designed the current study. Together, we administered an anonymous online survey to the congregation in October of 2016. Given that this was a pilot study, the survey was only open for four days. The survey was disseminated through the church’s mailing list, posted on the church’s website, and announced in the church bulletin. Respondents provided informed consent. No data were collected on congregants who declined to participate, so a completion rate was not calculated. According to the church, official membership is approximately 300 congregants, and Sunday worship services yield an average weekly attendance of 500 congregants. Respondents received a $10 gift card. Respondents were required to be English-speaking Korean-American adults (over 17 years of age) and residents of the greater Los Angeles area. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation. Funding was provided by the Louisville Institute, which did not play any role in data collection or interpretation.

Measures

Measures used in this study are described in detail in the online supplementary materials. In brief, sleep disturbances were measured using an ordinal variable assessing the level of sleep problems over the past 30 days. Mental health outcomes included non-specific psychological distress (Kessler-6), perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale short version), loneliness (UCLA loneliness scale), and hazardous drinking (Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test -Concise). Suicidal ideation and treatment seeking behaviors/perceived need for help were measured using dichotomous self-report items drawn from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. All measures have been validated and have been used in numerous studies (see online supplemental materials for description of measures and citations).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe the prevalence of sleep disturbances and mental health outcomes. Multivariable linear and logistic regression models were used to examine the relations between sleep disturbances and mental health outcomes, adjusted for age and sex. For all analyses, alpha was set at a=0.05 (two-tailed). Results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were performed using STATA IC 15.

RESULTS

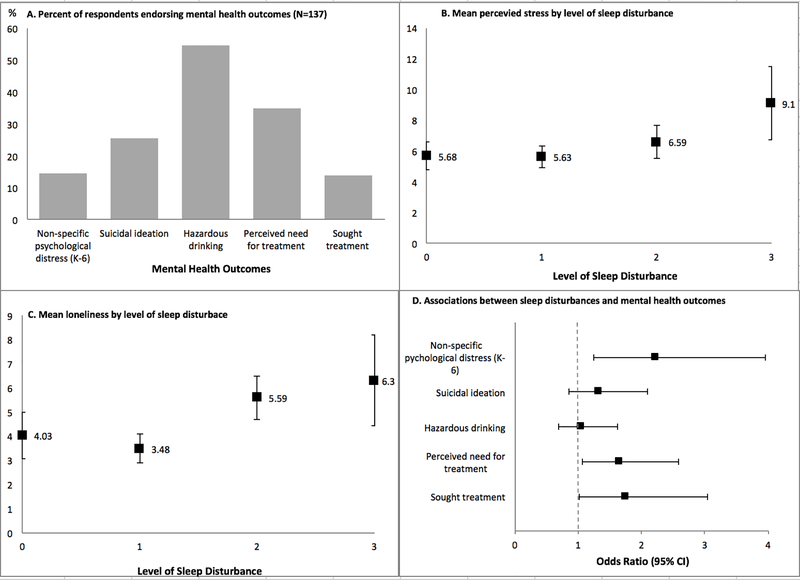

A total of 137 Korean-American respondents completed the online survey. About 45% of the sample was male, the average age was approximately 30 years, most (96%) of the sample had at least some college education, and most (73%) were born in the United States (the majority of those who were born in Korea immigrated to the United States more than ten years ago). The prevalence of mental health problems in the sample are depicted in Figure 1A. About 25% (n=34) of the sample reported no sleep disturbances, 46% (n=64) reported mild sleep disturbances, 21% (n=29) reported moderate sleep disturbances, and 7.3% (n=10) reported severe sleep disturbances.

Fig. 1.

The associations between sleep problems and mental health

After adjusting for age and sex, sleep disturbances were associated with greater odds of reporting non-specific psychological distress, perceiving the need for treatment, and seeking treatment (Figure 1D). Sleep disturbances were also associated with higher levels of perceived stress and loneliness (Figure 1B & 1C). However, sleep disturbances were not significantly associated with greater odds of reporting lifetime suicidal ideation or hazardous drinking over the past year (Figure 1D).

DISCUSSION

Our main findings suggest that administering screenings through the church is an effective way to screen for sleep problems among Korean-Americans. The majority of our sample had at least mild sleep disturbances, with a significant percentage having moderate to severe sleep disturbances. These sleep disturbances were associated with several mental health problems, including non-specific psychological distress, perceived stress, loneliness, treatment seeking behaviors, and perceived need for help. Surprisingly, sleep disturbances were not significantly associated with suicidal ideation, despite prior literature that would suggest an association (Bernert, Kim, Iwata, & Perlis, 2015). However, it is still possible that sleep disturbances may be associated with making suicide plans or attempts, which we did not examine in this study. Also, sleep disturbances were not associated with hazardous drinking, even though alcohol use is prevalent among Korean-Americans and has been known to denigrate sleep quality (Thakkar, Sharma, & Sahota, 2015). The insignificant findings may have been a result of the small sample size, as well as the fact that the sample consisted primarily of second-generation church-attending Korean-Americans living in Los Angeles who are proficient in English. Drawing a larger sample with more first generation Korean-Americans may have produced different results. Still, our preliminary findings open the possibility that complaining about sleep disturbances –similar to somatic symptoms –may be an idiom of distress that is a more culturally acceptable (and less stigmatizing) than admitting psychological suffering.

In light of our findings, we see two major practice implications. First, primary care providers should be sure to screen or interview for sleep disturbances when treating Korean-American patients, and can inquire further about mental health problems among patients with severe sleep problems. Discussing sleep problems may be a softer point of entry into conversations about mental health, and referrals can be made to appropriate levels of care (e.g. integrated care or specialized psychiatric treatment). Screening for sleep disturbances can be important for preventing future psychiatric disorders (Ford & Kamerow, 1989). But this implication relies heavily on whether Korean-Americans seek out professional services in the first place. And so the second practice implication is that churches can help administer sleep screenings in the community. Individuals who screen positive for severe sleep problems at church can be provided with information about sleep hygiene and stress reduction techniques, and receive referrals to mental health services. Further, as demonstrated by the current study, churches can administer screenings relatively quickly and easily online. However, further translational research is needed to explore the connections that can be made between churches and formal service providers in order to tailor interventions to Korean-Americans. A concerted effort will be needed to build relationships between pastors and clinicians, such that consultations and referrals can flow freely in both directions.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Banks S, & Dinges DF (2007). Behavioral and Physiological Consequences of Sleep Restriction. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 3(5), 519–528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benca RM, Obermeyer WH, Thisted RA, & Gillin JC (1992). Sleep and psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49(8), 651–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernert RA, Kim JS, Iwata NG, & Perlis ML (2015). Sleep disturbances as an evidence-based suicide risk factor. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(3), 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford DE, & Kamerow DB (1989). Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders: an opportunity for prevention? Jama, 262(11), 1479–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MT (1995). Cultural influences on depression in Korean Americans. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 33(2), 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang KY, & Lee MH (1994). Prevalence of depression and somatic symptoms among Korean elderly immigrants. Yonsei Medical Journal, 35(2), 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S-Y, & Bernstein KS (2008). Depression and Korean American immigrants. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 22(1), 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JK (2002). Help-seeking behaviors by Korean immigrants for depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 23(5), 461–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social P, & Trends D (2012). The Rise of Asian Americans. Washington, DC: Pew Social & Demographic Trends. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar MM, Sharma R, & Sahota P (2015). Alcohol disrupts sleep homeostasis. Alcohol, 49(4), 299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.