SUMMARY

Invasive meningococcal disease is a rare but serious infection caused by Neisseria meningitidis

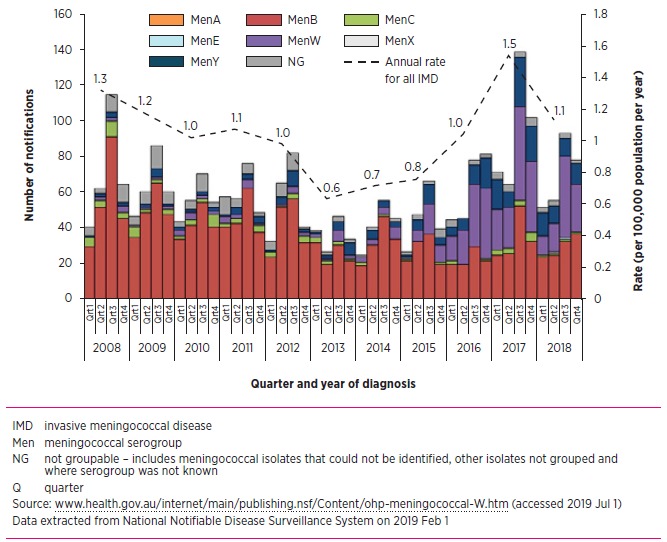

Serogroup B was the predominant serogroup causing invasive meningococcal disease in Australia until 2015. Serogroup W disease has increased substantially since 2014, and in 2017, serogroups B and W caused similar numbers of invasive disease cases

Vaccines against serogroups A, C, W, Y and B are available for anyone who wishes to reduce the risk of meningococcal disease

Vaccination is strongly recommended for people in high-risk age or population groups. These are children under 2 years, 15–19 year olds, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, and people with medical, occupational, behavioural or travel-related risk factors for invasive meningococcal disease

Meningococcal ACWY vaccine is funded under the National Immunisation Program for babies aged 12 months. Since April 2019, it has been funded for year 10 students through a school program. There are additional state and territory-based programs for both meningococcal ACWY and meningococcal B vaccines

Keywords: immunisation, meningitis, meningococcal vaccines

Introduction

Neisseria meningitidis is normally a commensal of the nasopharynx. However, it has the potential to invade the mucosa and cause invasive meningococcal disease, which most commonly presents as meningitis, septicaemia or both. There are 13 serogroups of N. meningitidis. Groups A, B, C, W135, Y and X cause the majority of disease.1

Transmission occurs via large-droplet spread or direct contact with oral secretions. Carriage rates vary by population worldwide and by age. Asymptomatic carriage is most common in adolescents and young adults.2 The incidence of invasive disease is highest in 0–4 year olds, especially infants, with a secondary peak in late adolescence and young adults. Invasive meningococcal disease is more common in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Risk factors

Risk factors for invasive disease include immune deficiencies such as asplenia, complement deficiencies and haemoglobinopathies, smoking, living in close quarters with other people, occupational exposure to N. meningitidis, and travel to highly endemic countries.

Incidence of disease

The incidence of invasive disease in Australia remains low, but has been increasing in recent years, with significant shifts in serogroup predominance as shown in the Figure. Universal meningococcal C vaccination was introduced to the National Immunisation Program in 2003 and resulted in a 94% reduction in serogroup C disease by 2017. Serogroup B has been the dominant serogroup in Australia for two decades, although its incidence has declined naturally in recent years even before the availability of meningococcal B vaccines.3 Since 2014, serogroups W and Y have caused increased cases of invasive disease.

Fig.

Quarterly cases and annual rate of invasive meningococcal disease in Australia (1 January 2008 to 31 December 2018) by serogroup

Meningococcal vaccines and recommendations

There are currently two groups of meningococcal vaccines available in Australia:

conjugate vaccines for protection against serogroups A, C, W and Y

recombinant protein-based vaccines for protection against serogroup B.

Conjugate vaccines against serogroup C alone remain available as catch-up vaccines, e.g. NeisVac-C and Menitorix (the Hib-MenC vaccine). Polysaccharide vaccines are no longer supplied or recommended for use in Australia.

Quadrivalent meningococcal (MenACWY) conjugate vaccines

Three quadrivalent conjugate vaccines against groups A, C, W and Y are currently available. They contain capsular polysaccharide antigens conjugated to a protein carrier:

Nimenrix – tetanus toxoid carrier

Menveo – diphtheria CRM197 carrier

Menactra – diphtheria toxoid carrier.

Indications and dosing schedules recommended by the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation vary by age and risk,4 and are outlined in the Table. A single dose of Nimenrix is funded on the National Immunisation Program for babies aged 12 months. Since April 2019, year 10 students (aged 14–16 years) can receive the vaccine via a school-based program, with a catch-up dose available through general practice for 15–19 year olds who missed it at school. In recent years, individual states and territories have funded MenACWY vaccines for adolescents or provided them extensively, especially to high-risk age groups for control of outbreaks.

Table. Meningococcal vaccine 2019 recommendations by age and risk group.

| Medically at risk | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who should be vaccinated? | Those with medical risk factors for invasive meningococcal disease, including: • complement deficiencies • current or future treatment with eculizumab • haemoglobinopathies • haematopoietic stem cell transplant • functional/anatomical asplenia • people living with HIV |

||||||||

| Which vaccine(s) are recommended? | MenACWY MenB |

||||||||

| Which vaccine(s) are NIP funded? | Nil | ||||||||

| 6 weeks – 5 months | 6–8 months | 9–11 months | 12–23 months | ≥2 years | |||||

| MenACWY | MenACWY dosing schedule by age at first dose | 4 doses Minimum 8-week intervals. 4th dose at 12 months of age or 8 weeks after 3rd dose, whichever is later |

3 doses Minimum 8-week intervals. 3rd dose at 12 months of age or 8 weeks after 2nd dose, whichever is later |

3 doses Minimum 8-week intervals. 3rd dose at 12 months of age or 8 weeks after 2nd dose, whichever is later |

2 doses Minimum 8-week interval |

2 doses Minimum 8-week interval |

|||

| Preferred brands (MenACWY) | Menveo or Nimenrix (Menactra not registered for use for this age group) |

Menveo, Nimenrix or Menactra* | Menveo or Nimenrix preferred to Menactra* | ||||||

| Further MenACWY booster doses required? | Yes, if ongoing increased risk of invasive meningococcal disease If age ≤6 when completed initial MenACWY vaccination course, give MenACWY booster 3 years after primary schedule, then every 5 years If age ≥7 when completed course, give MenACWY booster every 5 years |

||||||||

| 6 weeks–5 months | 6–11 months | 12 months–9 years | ≥10 years | ||||||

| MenB | MenB dosing schedule by age at first dose | Bexsero: 4 doses, minimum 8-week intervals, 4th dose at 12 months or 8 weeks after 3rd dose, whichever is later | Bexsero: 3 doses, minimum 8-week intervals, 3rd dose at 12 months or 8 weeks after 2nd dose, whichever is later | Bexsero: 2 doses, minimum 8-week interval | Bexsero: 2 doses, minimum 8-week interval Trumenba: 3 doses. Dose 2 should be ≥4 weeks after dose 1. Dose 3 ≥4 months after dose 2 and ≥6 months after dose 1 |

||||

| Table continued… | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy individuals | Occupationally at risk | Travellers | ||||||

| Who should be vaccinated? | Anyone aged ≥6 weeks who wishes to reduce their risk of invasive meningococcal disease, and in particular the following high-risk demographics: • infants aged <2 years • adolescents aged 15–19 years • Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged <15 years • adults aged 20–24 years who live in close quarters (e.g. military, student accommodation) • adults aged 20–24 years who smoke |

E.g. laboratory workers who handle Neisseria meningitidis | Travellers aged ≥6 weeks travelling to a country endemic for meningococcal A, C, W or Y, as well as Hajj pilgrims | |||||

| Which vaccine(s) are recommended? | • MenACWY • MenB |

MenACWY MenB |

MenACWY | |||||

| Which vaccine(s) are NIP funded? | National Immunisation Program: Nimenrix (MenACWY) is funded at 12 months (GP) and at School Year 10 (14–16 years, school-based program), with catch-up for 15–19 year olds who have not received a dose previously (GP based). | Nil | Nil | |||||

| 6 weeks–5 months | 6–8 months | 9–11 months | 12–23 months | ≥2 years | - | - | ||

| MenACWY | 3 doses Minimum 8-week intervals 3rd dose at 12 months of age or 8 weeks after 2nd dose, whichever is later |

2 doses 2nd dose at 12 months of age |

2 doses 2nd dose at 12 months of age |

Nimenrix: 1 dose Menveo/ Menactra: 2 doses, 8 weeks apart |

One dose | Dosing depends on presence of medical risk factors or not | Dosing depends on presence of medical risk factors or not | |

| Menveo or Nimenrix (Menactra not registered for use for this age group) |

Menveo, Nimenrix or Menactra* | Menveo or Nimenrix preferred to Menactra* | Menveo or Nimenrix preferred to Menactra* | Menveo or Nimenrix preferred to Menactra* | ||||

| No, not required | Yes, every 5 years | Yes, every 5 years if ongoing risk | ||||||

| 6 weeks–11 months | 12 months–9 years | ≥10 years | - | - | ||||

| MenB | Bexsero: 3 doses Minimum 8-week intervals, 3rd dose at 12 months or 8 weeks after 2nd dose, whichever is later |

Bexsero: 2 doses Minimum 8-week interval |

Bexsero: 2 doses, minimum 8-week interval Trumenba: 2 doses, minimum 6-month interval |

Dosing depends on presence of medical risk factors or not | MenB is not routinely recommended for travellers | |||

* Menactra should not be co-administered with Prevenar 13

Men meningococcal serogroup

NIP National Immunisation Program

These data are summarised from the online Australian Immunisation Handbook, December 2018.4

An A3 single-page version of this table is available online.

Nimenrix and Menveo induce a slightly better antibody level and persistence than Menactra in individuals over two years of age,5,6 and are the preferred brands above this age.4 For those who require more than one dose for the primary course, it is preferable to use the same brand. However, if it is unavailable, an alternate age-appropriate brand can be used to complete the course.

Protective effectiveness of MenACWY vaccines may decline over time. An observational study in the USA showed that among adolescents, the effectiveness of Menactra in adolescents against all serogroups was highest in the first year after vaccination (79%), but decreased to 61% after 3–8 years.7 Revaccination of adolescents is safe, but is not routinely recommended in Australia.

MenACWY vaccines are well tolerated and severe adverse events are rare. They can be co-administered with other routine vaccines in the National Immunisation Program with one exception – Menactra should not be co-administered with the pneumococcal vaccine Prevenar 13, as this may reduce the immune response to some pneumococcal serotypes.8 If they are both used, plan to give Prevenar 13 first, followed by Menactra at least four weeks later if possible. If Menactra and Prevenar 13 are inadvertently co-administered, a dose of Prevenar 13 should be repeated after an interval of at least eight weeks.4

Recombinant meningococcal B (MenB) vaccines

Two recombinant protein-based multicomponent vaccines against serogroup B disease are currently available:

Bexsero (also called MenB-MC) – contains multiple recombinant protein components and outer membrane vesicles of a strain of serogroup B meningococcus

Trumenba – contains two subfamilies of factor-H binding protein (fHBP).

Indications and dosing schedules by age are summarised in the Table. MenB vaccines are currently not funded on the National Immunisation Program, but are available by private prescription. In South Australia, they are available through a state-based program.

Given the low incidence of meningococcal B disease, vaccine efficacy in pre-approval studies was inferred from immune responses to the component antigens, rather than from clinical end points.

Bexsero (MenB-MC) can be used from age six weeks, according to the Australian Immunisation Handbook.4 A meta-analysis of immunogenicity studies found that 92% of children and adolescents achieved seroconversion 30 days after the primary vaccination course. However the long-term immunogenicity against some strains was suboptimal.9 Early effectiveness data from the UK, where universal MenB-MC vaccination was introduced in 2015, showed that a two-dose primary regimen was 82.9% effective (95% confidence interval 24.1–95.2) against all strains of meningococcal B in infants, observed up to 10 months after vaccination.10 The cost-effectiveness of universal MenB-MC vaccination is affected by the country-specific incidence of meningococcal B disease.11 The incidence in Australia is relatively low compared to countries that adopted universal vaccination, at 0.47 cases per 100 000 in 2015.3

Trumenba is registered for use from 10 years of age. Assessment of its clinical effectiveness is not yet available. Bexsero and Trumenba are not interchangeable and the same brand must be used to complete the vaccination course. Bexsero contains four major antigens that are preserved across multiple species of Neisseria, and may provide some protection against other capsular groups. However the extent of clinically important cross-protection is not known.12,13

MenB vaccines can be co-administered with MenACWY vaccines as well as other routine vaccinations. Fever is a very common adverse event following administration of Bexsero in young children and is more likely if Bexsero is co-administered with other vaccines. This risk can be reduced by separating administration of Bexsero from other vaccines (e.g. by at least three days). Prophylactic paracetamol is recommended for all children under two years receiving Bexsero in Australia.4

Conclusion

Safe and effective vaccines are available for prevention of invasive meningococcal disease caused by the most dominant serogroups in Australia. Primary care immunisation service providers are important for facilitating widespread uptake of meningococcal vaccines. MenACWY vaccine is provided for children aged 12 months and adolescents under the National Immunisation Program.

The MenACWY and MenB vaccines are strongly recommended for individuals at increased risk of invasive meningococcal disease. However, only the MenACWY vaccine is recommended for people travelling to regions where serogroups A, C, W, or Y are endemic. Health professionals should look out for at-risk patients and discuss vaccination options with them. Meningococcal vaccination is available for anyone who would like to reduce the risk of invasive meningococcal disease.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Caugant DA, Maiden MC. Meningococcal carriage and disease--population biology and evolution. Vaccine 2009;27 Suppl 2:B64-70. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen H, May M, Bowen L, Hickman M, Trotter CL. Meningococcal carriage by age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:853-61. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70251-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archer BN, Chiu CK, Jayasinghe SH, Richmond PC, McVernon J, Lahra MM, et al. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) Meningococcal Working Party Epidemiology of invasive meningococcal B disease in Australia, 1999-2015: priority populations for vaccination. Med J Aust 2017;207:382-7. 10.5694/mja16.01340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). Australian immunisation handbook. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2018. https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au [cited 2019 Jul 1]

- 5.Baxter R, Baine Y, Kolhe D, Baccarini CI, Miller JM, Van der Wielen M. Five-year antibody persistence and booster response to a single dose of meningococcal A, C, W and Y tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine in adolescents and young adults: an open, randomized trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34:1236-43. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baxter R, Reisinger K, Block SL, Izu A, Odrljin T, Dull P. Antibody persistence and booster response of a quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine in adolescents. J Pediatr 2014;164:1409-15 e4. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Cohn AC, MacNeil JR, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Reingold A, Schaffner W, et al. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) Team and MeningNet Surveillance Partners Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) Team and MeningNet Surveillance Partners. Effectiveness and duration of protection of one dose of a meningococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20162193. 10.1542/peds.2016-2193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics Prevention and control of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Pediatrics 2013;132:e1463. 10.1542/peds.2013-2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flacco ME, Manzoli L, Rosso A, Marzuillo C, Bergamini M, Stefanati A, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the multicomponent meningococcal B vaccine (4CMenB) in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:461-72. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30048-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parikh SR, Andrews NJ, Beebeejaun K, Campbell H, Ribeiro S, Ward C, et al. Effectiveness and impact of a reduced infant schedule of 4CMenB vaccine against group B meningococcal disease in England: a national observational cohort study. Lancet 2016;388:2775-82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31921-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Expert opinion on the introduction of the meningococcal B (4CMenB) vaccine in the EU/EEA. Stockholm: ECDC; 2017. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/expert-opinion-introduction-meningococcal-b-4cmenb-vaccine-eueea [cited 2019 Jul 1]

- 12.Petousis-Harris H, Paynter J, Morgan J, Saxton P, McArdle B, Goodyear-Smith F, et al. Effectiveness of a group B outer membrane vesicle meningococcal vaccine against gonorrhoea in New Zealand: a retrospective case-control study. Lancet 2017;390:1603-10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31449-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladhani SN, Giuliani MM, Biolchi A, Pizza M, Beebeejaun K, Lucidarme J, et al. Effectiveness of meningococcal B vaccine against endemic hypervirulent Neisseria meningitidis W strain, England. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:309-11. 10.3201/eid2202.150369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FURTHER READING

- National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance. Meningococcal vaccines – FAQs. www.ncirs.org.au/ncirs-fact-sheets-faqs/meningococcal-vaccines-faqs [cited 2019 Jul 1]

- National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance. Meningococcal vaccines for Australians. Fact sheet April 2019. www.ncirs.org.au/ncirs-fact-sheets-faqs/meningococcal-vaccines-australians [cited 2019 Jul 1]