Abstract

BACKGROUND: We conducted a phase I/II clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of eribulin and olaparib in a tablet form (EO study) for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients. We hypothesized that somatic BRCA mutations and homologous recombination repair (HRR)-related gene alterations might affect efficacy. METHODS: Our analyses identified mutations in HRR-related genes and BRCA1/2, and we subsequently evaluated their association to response by the EO study participants. Tissue specimens were obtained from primary or metastatic lesion. Tissue specimens were examined for gene mutations or protein expression using a Foundation Medicine gene panel and immunohistochemistry. RESULTS: In the 32 tissue specimens collected, we detected 33 gene mutations, with the most frequent nonsynonymous mutations found in TP53. The objective response rates (ORRs) in patients with and without HRR-related gene mutation were 33.3% and 40%, respectively (P = .732), and the ORRs in patients with and without somatic BRCA mutations were 60% and 33.3%, respectively (P = .264), with the ORR numerically higher in the somatic BRCA-mutation group but not statistically significant. There was no correlation between immunohistochemistry status and response or between BRCA status or HRR-related gene mutation and survival. Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that EGFR-negative patients had a tendency for better progression-free survival (log-rank P = .059) and significantly better overall survival (log-rank P = .046); however, there was no correlation between the status of other immunohistochemistry markers and survival. CONCLUSION: These findings suggested somatic BRCA mutation and EGFR-negativity as a potential biomarker for predicting the efficacy of eribulin/olaparib combination therapy. (UMIN000018721).

Introduction

Breast cancer is the fourth most common cancer in Japanese women and accounted for an estimated 9806 deaths in 2003 [1]. Although there have been major improvements in oncologic treatments, breast cancers frequently recur after primary treatment, and following recurrence, these cancers are incurable. Treatment options for inoperable advanced, metastatic, or recurrent breast cancer includes hormone therapy, anti-human epidermal receptor type 2 (HER2) therapy, and chemotherapy, depending on results from pathological examination of the tumor specimens.

Anthracycline and taxane are the major cytotoxic agents representing highly efficacious chemotherapeutics. A chemotherapy regimen including an anthracycline or taxane agent can also be administered as part of first- or second-line chemotherapy for inoperable advanced, metastatic, or recurrent breast cancer; however, these agents are frequently not selected for first-or second-line chemotherapy, because these drugs might have been administered as neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy during primary treatment. Other cytotoxic agents, such as eribulin, capecitabine, vinorelbine, and gemcitabine, can be selected for systemic chemotherapy in patients previously treated with anthracycline and taxane agents [2]. Eribulin is a non-taxane microtubule inhibitor reported to improve overall survival (OS) of patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with anthracycline and taxane and relative to treatment with physicians’ choice according to findings from the EMBRACE trial [3]. Since report of the EMBRACE results, eribulin has been considered a standard of care for this population of breast cancer patients and was approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency in Japan in 2010.

In breast cancer, hormone-receptor-negative, HER2-negative breast cancer is referred to as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and estimated to account for 10% to 20% of all breast cancers. TNBC occurs at a younger age and with a higher tumor grade, highly proliferative tumor characteristics, and poor survival as compared with other types of breast cancers. The treatment options for this type of breast cancer are limited to chemotherapy; therefore, there is a large unmet medical need for new treatment strategies for patients with TNBC [4], [5].

Olaparib (AZD2281) is a potent polyadenosine 5′-diphosphoribose (poly-ADP ribose) polymerase (PARP)-1, −2, and− 3 inhibitor currently being developed as an oral therapy both as monotherapy, including tumor maintenance, and in combination with other anticancer agents. PARP inhibition is a novel approach for targeting tumors with deficiencies in DNA-repair mechanisms. PARP enzymes are essential for repairing DNA single-strand breaks (SSBs), and inhibiting PARPs leads to the persistence of SSBs, which are then converted to more serious DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) during DNA replication. During the process of cell division, DSBs can be efficiently repaired in normal cells through homologous recombination repair (HRR); however, tumors with HRR deficiencies (HRD), such as serous ovarian cancers and breast cancer, cannot accurately repair the DNA damage, resulting in accumulating damaged DNA becoming potentially lethal to tumor cells. In such tumor types, olaparib might potentially serve as an efficacious and less toxic cancer treatment as compared with currently available chemotherapy regimens.

Olaparib inhibits selected tumor-cell lines in vitro and in xenograft and primary explant models, as well as in genetic breast cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA) knockout models, either as standalone treatment or in combination with established chemotherapeutics. Cells deficient in HRR factors, notably BRCA1/2, are particularly sensitive to olaparib treatment. PARP inhibitors, such as olaparib, might also enhance the DNA-damaging effects of other chemotherapy agents [6], [7], [8], [9]. BRCA1-related breast cancer accounts for 5% of all breast cancers [10]. Although >50% of BRCA1-mutation carriers have TNBC according to pathological analyses [11], [12], patients with TNBC do not necessarily harbor BRCA1 mutations. However, previous studies report that TNBC patients harboring wild-type BRCA1 frequently exhibit downregulated BRCA1 expression or alterations in BRCA1 function, which might occur through methylation of the BRCA1 promoter or overexpression of the protein that normally regulates BRCA1 expression [13], [14], [15], [16].

Mutations in numerous HRR genes lead to phenotypes similar to those associated with mutated BRCA1/2, a situation called BRCAness. Previous studies report an elevated risk for cancer development associated with HRR deficiencies, such those associated with as RAD51, BRIP1, PALB2, and FANCA mutation. Actually, 50% of high-grade serous ovarian cancers involve at least one HRR-modulating gene alteration. In a clinical trial for high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGS-OvCa), olaparib maintenance therapy doubled the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with BRCA1/2 germline-mutation, platinum-sensitive HGS-OvCa [17]. Additionally, in a phase II study, olaparib showed efficacy as maintenance therapy for platinum-sensitive relapsed HGS-OvCa patients, regardless of germline BRCA1/2 status [18]. Moreover, maintenance therapy involving niraparib and rucaparib showed a significant response and prolonged PFS for patients with HGS-OvCa, regardless of BRCA1/2 status but especially in those with non- BRCA1/2 -related HRR deficiency [19], [20]. However, In TNBC, the clinical significance of HRD to PARP inhibition has been not evaluated.

Here, we conducted a phase I/II clinical trial (EO study) to evaluate the efficacy of eribulin combined with the tablet form of olaparib for TNBC patients. We enrolled 24 patients in phase I, and one patient in the first cohort experienced dose-limiting toxicity (DLT). The recommended phase II dose (RP2D) was established as the approved dose for both drugs (olaparib: 300 mg twice daily with eribulin 1.4 mg/m2). All 24 patients received RP2D in phase II, with the median number of courses administered in phase II at 5.5 (range: 1–28). For the 22 evaluable patients, the response rate was 18.2% [complete response (CR): 0; partial response (PR): 4; 95% confidence interval (CI): 6.5–36.9)]. Median PFS and OS were 4.2 (95% CI: 3.0–7.4) and 14.5 (95% CI: 4.8–22.0), respectively [21].

We hypothesized that BRCA mutations and HRR-related gene alterations might contribute to the efficacy results obtained from the EO study. Therefore, we identified the existence of mutations in HRR-related genes and BRCA1/2 and evaluated their association with patient response to eribulin/olaparib combination therapy among the participants in the EO study.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Center, Tokyo (2012-236), and complied with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. All patients had participated in the phase I/II EO study. The EO study is an open-label, non-randomized, multi-center, dose-escalation study of olaparib in combination with eribulin mesylate aimed to assess safety, tolerability, and efficacy in patients with recurrent or metastatic TNBC. The EO study is a multi-institutional study that includes seven sites in Japan.

Tissue specimens from metastatic/primary sites were obtained at the time of surgery or biopsy from each site. Germline BRCA mutations were analyzed in patients who had consented to provide two blood samples for confirmatory germline BRCA1/2-mutation testing using the Myriad Genetics BRCA test (Myriad BRACAnalysis; Myriad Genetics, Salt Lake City, UT, USA). Patients with a known BRCA1/2 mutation were analyzed on the basis of this information.

Gene Analysis

Archival tissue samples were examined for gene alterations using a Foundation Medicine, Inc. (FMI) gene panel. Pathogenic or likely pathogenic gene alterations were extracted from all detected gene alterations using the FMI data dictionary. This dictionary uses the COSMIC database, relevant literature, and internal evidence to determine the reportable status of an alteration. We chose previously defined HRR-related genes, including BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, FANCA, FANCI, FANCL, FANCC, RAD50, RAD51, RAD51C, RAD54L, ATM, ATR, CHEK1, and CHEK2 [22]. Correlation between the presence of HRR-related gene mutation and patient cancer response to the combination therapy was determined.

Immunohistochemistry

We examined epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), cytokeratin 5/6 (CK5/6), (BRCA1/ 2, vimentin, zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1), and E-cadherin. Primary antibodies are presented in Table S1. For all antibodies, except that for ZEB1, antigens were retrieved with citrate buffer treatment at 121 °C for 10 min. The Envision method was used for the secondary antibody reaction, and diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride was used for the peroxidase reaction [23]. For the ZEB1 antibody, antigen was retrieved with Target Retrieval solution PH9 (TRS9; DAKO; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 98 °C for 40 min, and Histofine Simple Stain MAX-PO(G) (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) was used for the secondary antibody reaction.

For BRCA1 and BRCA2, the proportion of positive cells (score: 0–5) and staining intensity (score: 0–3) were considered [24], and the expression was regarded as positive when the sum of these scores was >2. In cases of a score of 2 with weak-internal positive staining, expression was regarded as equivocal. Cytoplasmic and/or membranous immunoreactive staining was regarded positive if ≥10% of the cells were stained, regardless of intensity. Moderate-to-strong membranous/cytoplasmic staining (2+ or 3+, respectively) in ≥10% of tumor cells was regarded as positive for EGFR only. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) results were independently evaluated by two researchers (A.S. and M.Y.) without knowledge of the clinical characteristics (Figure S1).

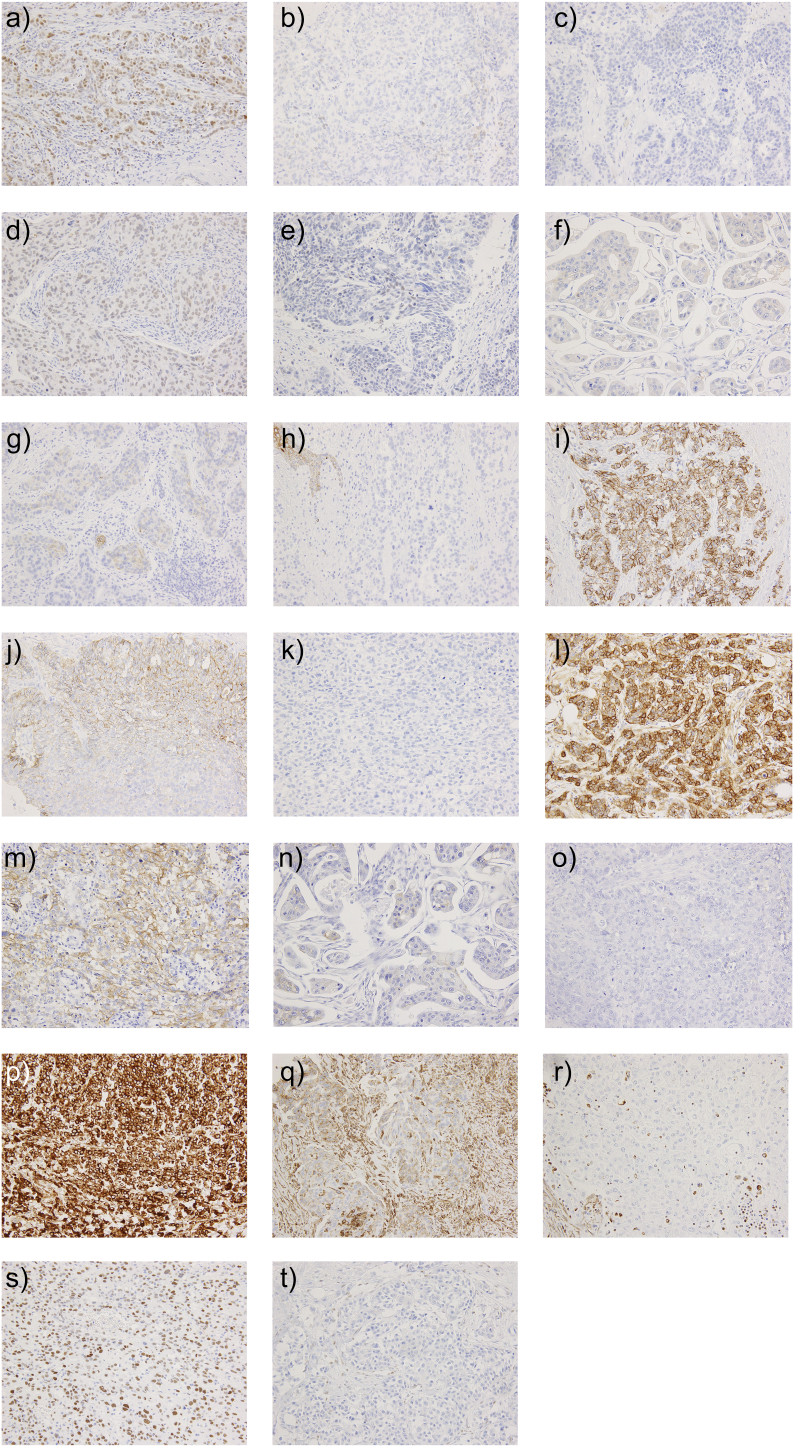

Supplementary Figure S1.

IHC analysis of cancer-marker status. (A) BRCA1 retained, (B) equivocal, and (C) loss. (D) BRCA2 retained, (E) equivocal, and (F) loss. (G) CK5/6-positive and (H) -negative. (I) E-cadherin diffuse positive, (J) focal positive, and (K) -negative. (L) EGFR 3+, (M) EGFR 2+, (N) EGFR 1+, and (O) EGFR 0. (P) Vimentin diffuse positive, (Q) focal positive, and (R) loss. (S) ZEB1-positive and (T) -negative.

BRCA1, breast cancer susceptibility gene 1; BRCA2, breast cancer susceptibility gene 2; CK5/6, cytokeratin 5/6; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IHC, immunohistochemical; ZEB1, zinc finger E-box binding homeobox

Results

Gene Expression, Amplification, and Homologous Deletion

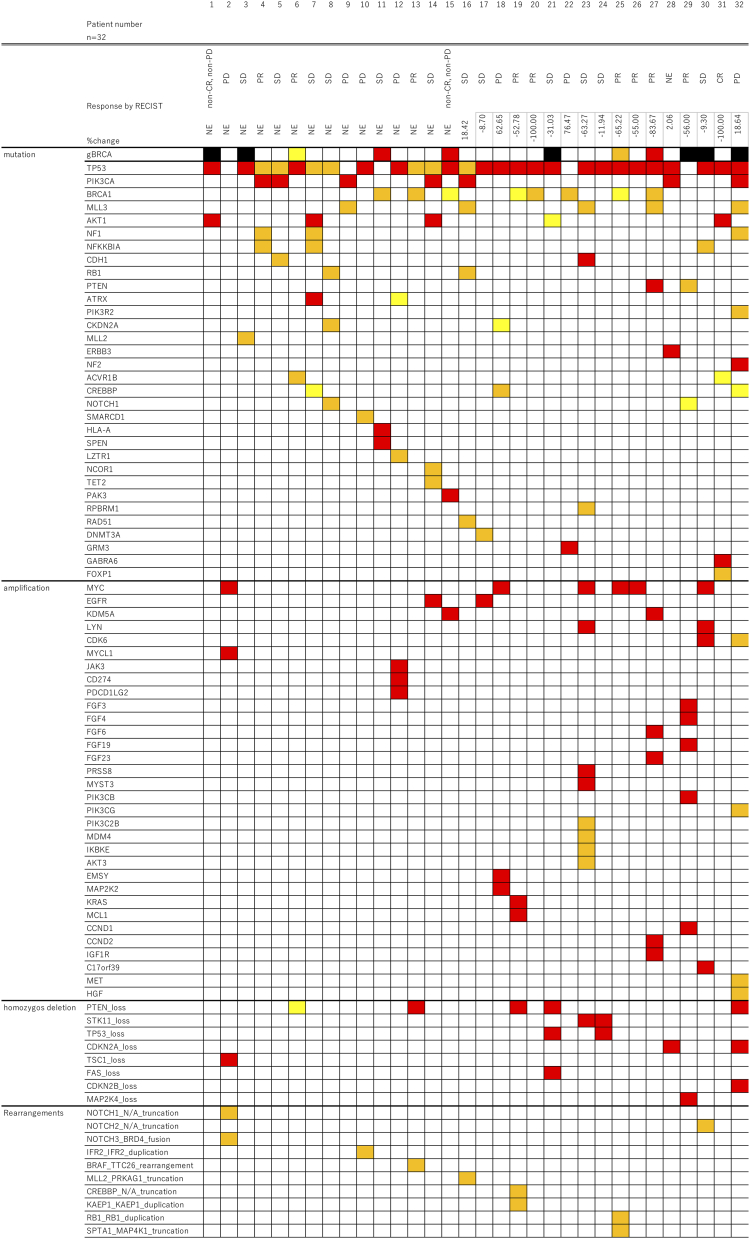

A total of 32 tissue specimens were collected, with 19 samples collected from the phase I trial and 13 samples from the phase II trial. Seventeen patients were treated at the recommended dose. Figure 1 shows the landscape of the gene mutations.

Figure 1.

The landscape of gene alterations in patients treated with the combination therapy of eribulin and olaparib. Red color indicates pathogenic mutations, orange color indicates likely pathogenic mutations, and yellow color indicates variants of uncertain significance. Genes without any alterations are not showed in this figure.

RECIST, response evaluation criteria in solid tumor; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

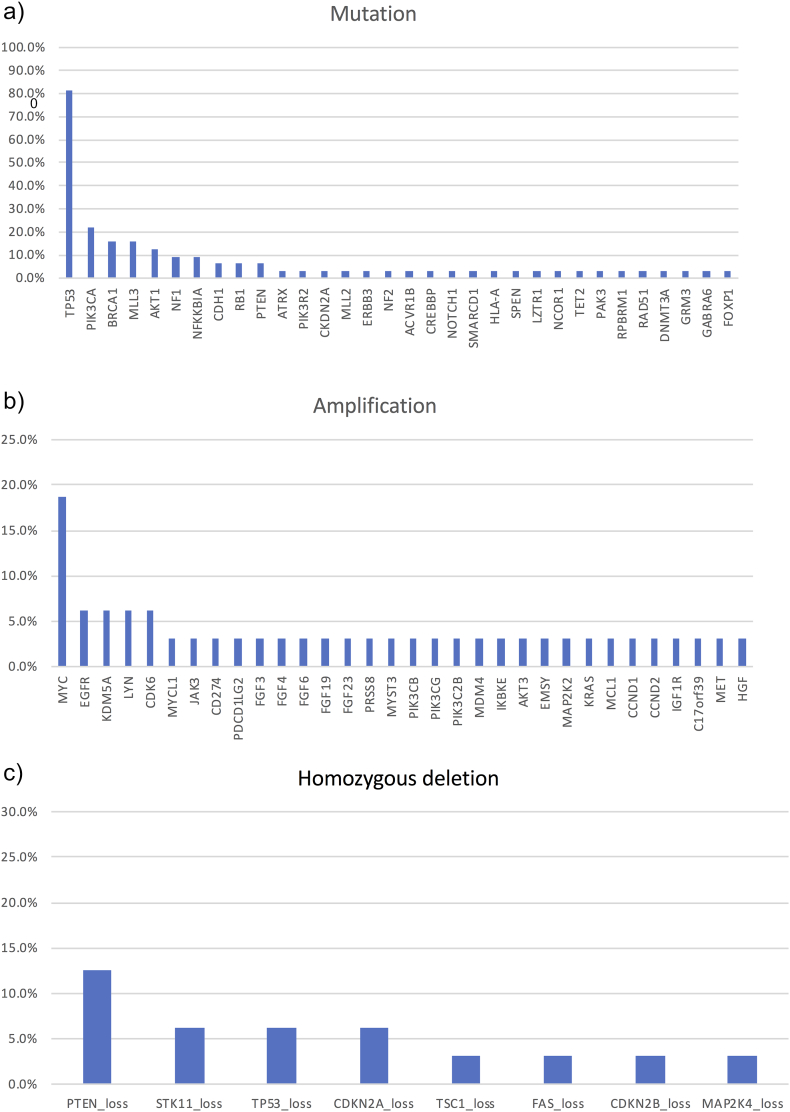

Thirty-three gene mutations were detected in the TNBC specimens. The most frequent nonsynonymous mutations were in TP53 (n = 27; 84.4%), PIK3CA (n = 7; 21.9%), BRCA1 (n = 5; 15.6%), MLL3 (n = 5; 15.6%), AKT1 (n = 4; 12.5%), NF1 (n = 3; 9.4%), NFKKBIA (n = 3; 9.4%), CHD1 (n = 2; 6.3%), RB1 (n = 2; 6.3%), and PTEN (n = 2; 6.3%) (Figure 2A). Detection of gene amplifications revealed the most frequent for MYC (n = 6; 18.8%), EGFR (n = 2; 6.3%), KDM5A (n = 2; 6.3%), LYN (n = 2; 6.3%), and CDK6 (n = 2; 6.3%) (Figure 2B). Eight homozygous deletions were detected, with the most frequent being the loss of PTEN (n = 4; 12.5%). As shown in Figure 2C, other frequently observed homozygous deletions included loss of STK11 (n = 2; 6.3%), TP53 (n = 2; 6.3%), and CDKN2A (n = 2; 6.3%). Additionally, we detected 10 gene rearrangements, and HRD, including BRCA1/2 mutations, were observed in nine patients (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Gene mutations, amplifications, and homozygous deletions in patients treated with combination therapy of eribulin and olaparib.

Response was evaluable in 29 patients. CR was observed in one patient (3.4%), and PR was observed in seven (24.1%). The ORR for CR and PR and the clinical benefit rate (CBR) for CR, PR, and stable disease were 34.5% and 75.9%, respectively. The ORRs in patients with HRD and without HRD were 33.3% and 40%, respectively (P = .732), and those for patients with and without somatic BRCA mutation were 60% and 33.3%, respectively (P = .264) (Table 1). ORR was numerically higher in the somatic BRCA-mutation group, although the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Response to eribulin/olaparib combination treatment by patients with somatic BRCA mutation or homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD)

| Objective response (%) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRD | n = 29 | pos (n = 9) | 3 (33.3%) | .732 |

| neg (n = 20) | 8 (40%) | |||

| Somatic BRCA Mutation | n = 29 | pos (n = 5) | 3 (60%) | .264 |

| neg (n = 24) | 8 (33.3%) |

pos: positive, neg: negative.

chi-Square test.

The response rate in patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutation (n = 5) was 40% (CR in 0 patients and PR in 2 patients). No PD was observed. This rate was higher than that in the overall population.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC analysis of the evaluable specimens revealed that BRCA1 was positive in 58.6% of the specimens, BRCA2 was positive in 53.6%, EGFR was positive in 42.9%, CK5/6 was positive in 13.8%, E-cadherin was positive in 10.7%, ZEB1 was positive in 10.7%, and vimentin was positive in 67.9%. There was no correlation between the IHC status of any of the markers evaluated and response to eribulin/olaparib combination therapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Response to eribulin/olaparib combination treatment by patients relative to immunohistochemistry status

| Responders | Non-responders | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 n = 29 |

pos | 17 (58.6%) | 5 | 12 | .260 |

| neg | 12 (41.4%) | 6 | 6 | ||

| BRCA2 n = 28 |

pos | 15 (53.6%) | 6 | 9 | .934 |

| neg | 13 (46.4%) | 5 | 8 | ||

| EGFR n = 28 |

pos | 12 (42.9%) | 4 | 8 | .576 |

| neg | 16 (57.1%) | 7 | 9 | ||

| CK5/6 n = 29 |

pos | 4 (13.8%) | 2 | 2 | .592 |

| neg | 25 (86.2%) | 9 | 16 | ||

| E-cadherin n = 28 |

pos | 3 (10.7%) | 0 | 3 | .140 |

| neg | 25 (89.3%) | 11 | 14 | ||

| ZEB1 n = 28 |

pos | 3 (10.7%) | 2 | 1 | .304 |

| neg | 25 (89.3%) | 9 | 16 | ||

| Vimentin n = 28 |

pos | 19 (67.9%) | 8 | 11 | .657 |

| neg | 9 (32.1%) | 3 | 6 |

pos: positive, neg: negative.

chi-square test.

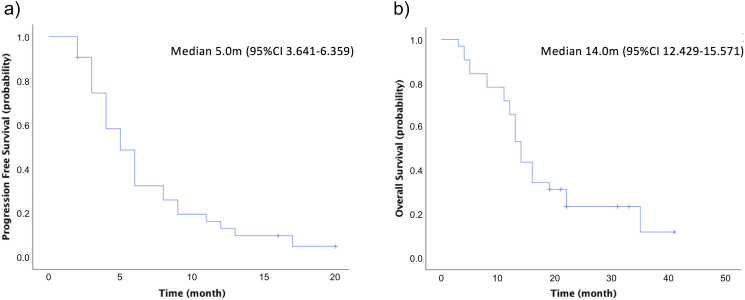

Survival Analysis According to Gene Alteration and IHC Status

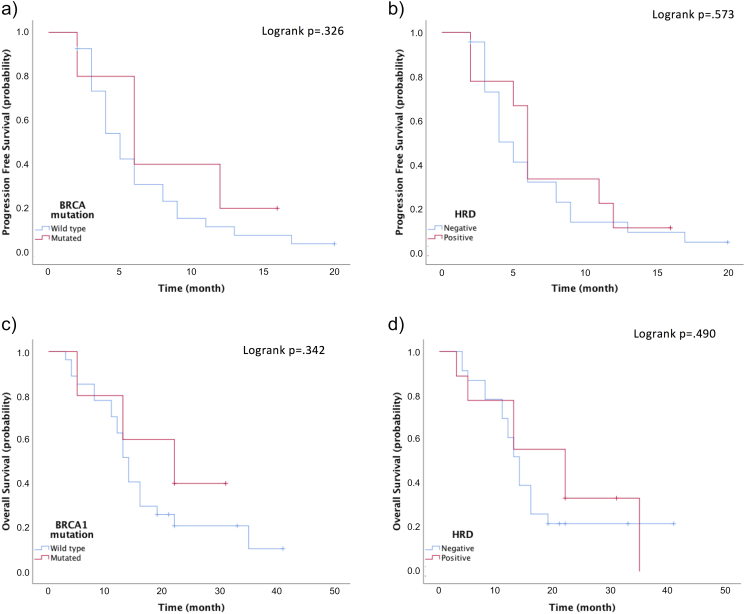

For the patients included in this study, the median PFS was 5.0 months (95% CI: 3.641–6.359) and median OS was 14.0 months (95% CI: 12.429–15.571) (Figure 3). There was no correlation between BRCA or HRD status and survival (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

PFS and OS rates. OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Figure 4.

PFS and OS according to BRCA status. (A, B) PFS and (C, D) OS according to somatic BRCA mutation and HRD. BRCA, breast cancer susceptibility gene; HRD, homologous recombination repair deficiency; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

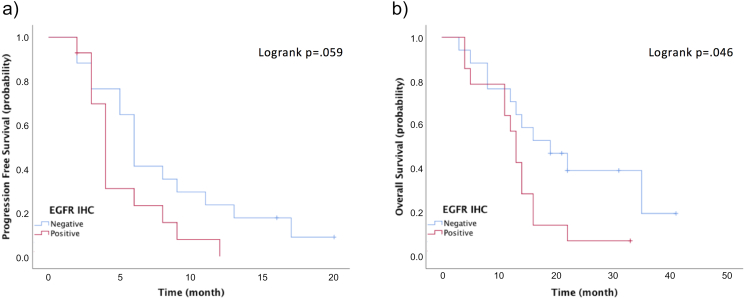

EGFR-negative patients according to IHC tended to have a better PFS (log-rank P = .059) and a significantly better OS (log-rank P = .046) (Figure S2). There was no correlation between the IHC status of other markers evaluated and survival.

Supplementary Figure S2.

PFS and OS according to EGFR status. (A) PFS and (B) OS according to IHC status of EGFR.

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IHC, immunohistochemical; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated correlations between response and HRD or IHC status in patients treated with the combination therapy of eribulin and olaparib in a phase the I/II trial. The combination therapy of eribulin and olaparib was well-tolerated and showed antitumor activity in patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC (response rate: 18.2%), with median PFS and median OS at 4.2 months (95% CI: 3.0–7.4) and 14.5 months (95% CI, 4.8–22.0), respectively. These findings support combination therapy with eribulin and olaparib as a promising new treatment for patients with advanced or metastatic TNBC.

Recent advances in research regarding HRD, including the use of olaparib for treating BRCA1/2-mutation carriers, has made HRD a potential biomarker for the treatment of TNBC. Assays that evaluate HRR capacity might help guide treatments using agents that induce or target DNA-damage repair. Niraparib is an FDA-approved PARP inhibitor used to treat ovarian cancer. In a phase-III study of niraparib, exploratory analyses were conducted in an HRD-positive subgroup, finding that the median PFS in patients with HRD-positive tumors harboring wild-type BRCA was longer in the niraparib group as compared with that in the placebo group [19]. Moreover, patients with HRD-positive tumors harboring a somatic BRCA mutation displayed similar reductions in the risk of disease progression as those observed in the cohort harboring a germline BRCA mutation. Additionally, niraparib treatment improved PFS in the HRD-negative subgroup.

Rucaparib is another FDA-approved PARP inhibitor that shows antitumor activity in patients with ovarian cancer. Rucaparib is approved for use in the treatment of patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer and induces prolonged PSF in patients with recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian carcinoma and who responded to platinum-based therapy associated with HRD [25]. In the present study, the ORR and CBR for the 32-patient cohort were 34.5% and 75.9%, respectively, and the frequency of nonsynonymous mutations was 100%, with the most common nonsynonymous mutation in TP53. These observed rates were higher than those previously reported [26]. Additionally, the frequency of gene amplification in the patients was 48.3%, with the most frequent being MYC. Moreover, we investigated correlations between HRD-related gene mutations and response rate to eribulin/olaparib combination therapy, finding that the ORR was numerically higher in the HRD group, although the difference was not statistically significant, and the CBR was similar between the HRD and non-HRD groups. This suggested that HRD might represent a potential biomarker for predicting the efficacy of combination therapy using olaparib with eribulin in TNBC patients.

In a previous study of combination therapy with carboplatin and eribulin in a neo-adjuvant setting, the pathological complete response (pCR) rate in BRCA1/2-mutation-positive patients was 66% (2/3 patients), and patients with HRD achieved higher pCR rates than non-HRD patients [27]. These data agreed with our results. Although phase-III studies of eribulin monotherapy [3], [28] and phase-I/II studies of monotherapy or combined therapy with eribulin have been reported [29], [30], [31], [32], there were data describing associated gene alterations.

The only report focusing on predictive factors in the efficacy of eribulin involved a pooled analysis of two phase-III trials [33]. One of the suspected mechanisms of eribulin action involves activity in the tumor microenvironment. Abnormal tumor vasculature leads to tumor aggressiveness, and eribulin induces the remodeling of abnormal tumor vasculature and eliminates inner tumor hypoxia [34], [35], [36]. Another possible mechanism involves suppression of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). An in vivo xenograft model showed that eribulin treatment reverses EMT and induces mesenchymal–epithelial transition, and surviving TNBC cells pretreated in vitro with eribulin for 7 days displayed decreased lung metastasis when assessed in an in vivo experimental metastasis model [35], [36]. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are also expected to be useful as predictive markers for eribulin efficacy during the treatment of patients with TNBC [37], and another study suggests that immune system status might correlate with eribulin efficacy [38].

In our study, EGFR-positive patients according to IHC tended to have a worse PFS and a significantly worse OS. EGFR-positivity has been reported as a prognostic factor of breast cancer [39]. But in in context of predicting efficacy of combination therapy of eribulin and olaparib, the importance of EGFR-positivity is unclear.

In conclusion, we investigated the status of epithelial and mesenchymal markers by IHC in response to combined eribulin/olaparib combination therapy. Our results showed that EGFR status was associated with better PFS and OS. The suspected mechanism associated with these results involved suppression of EMT by eribulin. Our findings also suggest that somatic BRCA mutations might serve as potential biomarkers for predicting the efficacy of combination therapy with eribulin and olaparib in patients with TNBC. Further analysis using a larger cohort is needed.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry in the present study

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the study staff, Tamie Sukigara, Ritsuko Nagasaka, Tomomi Yoshino, Noriko Tanabe.

Funding

This research was conducted with support from an Externally Sponsored Research Program of AstraZeneca (ESR-15-11262).

Ethical Standards

The present study was approved by the NCCH Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

A.S. and K.T. conceived and designed the study. A.S. and M.S. reviewed the IHC specimen. A.S. interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the submission of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest: A. Shimomura reports personal fees from Chugai Pharmatheutical, personal fees from Novartis Pharmatheutical, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Nippon Kayaku, personal fees and other from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Eisai, other from Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work; K. Yonemori reports personal fees from Eisai, personal fees from Taiho, outside the submitted work; M. Yoshida has nothing to disclose; T. Yoshida has nothing to disclose; H. Yasojima has nothing to disclose; N. Masuda reports grants and personal fees from Chugai, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from Eisai, grants and personal fees from Eli-Lilly, personal fees from Takeda, grants from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, grants from MSD, grants from Novartis, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, outside the submitted work; and Board of directors: Japan Breast Cancer Research Group Association; K. Aogi reports grants and personal fees from Eisai, personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work; M. Takahashi reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Eisai, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, personal fees from Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work; Y. Naito reports speakers’ bureau from Pfizer, speakers’ bureau from Taiho, speakers’ bureau from Nippon Kayaku, speakers’ bureau from Eli Lilly, speakers’ bureau from AstraZeneca, speakers’ bureau from Merck Serono, speakers’ bureau from Bayer, speakers’ bureau from Meiji Seika, research funding and speakers’ bureau from Roche Diagnostics, speakers’ bureau from Pfizer, speakers’ bureau from Novartis, speakers’ bureau from Chugai, speakers’ bureau from Pfizer, speakers’ bureau from Eisai, outside the submitted work; S. Shimizu has nothing to disclose; R. Nakamura has nothing to disclose; A. Hamada has nothing to disclose; H. Michimae has nothing to disclose; J. Hashimoto has nothing to disclose; H. Yamamoto has nothing to disclose; A. Kawachi has nothing to disclose; C. Shimizu reports personal fees from Astra Zeneca, personal fees from Eizai, during the conduct of the study; grants from Eli Lilly, grants and personal fees from Chugai, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, grants from MSD, outside the submitted work; Y. Fujiwara reports grants and other from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, grants and other from The Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare, Japan, during the conduct of the study; other from Astra Zeneca KK, other from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., other from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., other from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., other from Novartis Pharma KK, other from SRL Inc., outside the submitted work; K. Tamura reports grants from AstraZeneca, during the conduct of the study.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients. A copy of the written consent is available for review upon requests.

References

- 1.Cancer Information Service Center NCC. Cancer Information Service 2015 [Available from: http://ganjoho.jp/public/index.html.

- 2.Jinno H, Inokuchi M, Ito T, Kitamura K, Kutomi G, Sakai T. The Japanese Breast Cancer Society clinical practice guideline for surgical treatment of breast cancer, 2015 edition. Breast Cancer. 2016;23(3):367–377. doi: 10.1007/s12282-016-0671-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortes J, O’Shaughnessy J, Loesch D, Blum JL, Vahdat LT, Petrakova K. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):914–923. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, Parise CA, Caggiano V. Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California cancer Registry. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1721–1728. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakha EA, Tan DS, Foulkes WD, Ellis IO, Tutt A, Nielsen TO, et al. Are triple-negative tumours and basal-like breast cancer synonymous? Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(6):404; author reply 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434(7035):917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe N, Turner NC, Lord CJ, Kluzek K, Bialkowska A, Swift S. Deficiency in the repair of DNA damage by homologous recombination and sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2006;66(16):8109–8115. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menear KA, Adcock C, Alonso FC, Blackburn K, Copsey L, Drzewiecki J. Novel alkoxybenzamide inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18(14):3942–3945. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menear KA, Adcock C, Boulter R, Cockcroft XL, Copsey L, Cranston A. 4-[3-(4-cyclopropanecarbonylpiperazine-1-carbonyl)-4-fluorobenzyl]-2H-phthalazin- 1-one: a novel bioavailable inhibitor of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. J Med Chem. 2008;51(20):6581–6591. doi: 10.1021/jm8001263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robson M. Are BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast cancers different? Prognosis of BRCA1-associated breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18(21 Suppl):113S–8S. [PubMed]

- 11.Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS. Basal-like breast cancer and the BRCA1 phenotype. Oncogene. 2006;25(43):5846–5853. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atchley DP, Albarracin CT, Lopez A, Valero V, Amos CI, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients with BRCA-positive and BRCA-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(26):4282–4288. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner N, Tutt A, Ashworth A. Hallmarks of ’BRCAness’ in sporadic cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(10):814–819. doi: 10.1038/nrc1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyoshi Y, Murase K, Oh K. Basal-like subtype and BRCA1 dysfunction in breast cancers. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13(5):395–400. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0831-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abd El-Rehim DM, Ball G, Pinder SE, Rakha E, Paish C, Robertson JF. High-throughput protein expression analysis using tissue microarray technology of a large well-characterised series identifies biologically distinct classes of breast cancer confirming recent cDNA expression analyses. Int J Cancer. 2005;116(3):340–350. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner NC, Reis-Filho JS, Russell AM, Springall RJ, Ryder K, Steele D. BRCA1 dysfunction in sporadic basal-like breast cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26(14):2126–2132. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, Gebski V, Penson RT, Oza AM. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1382–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2154–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swisher EM, Lin KK, Oza AM, Scott CL, Giordano H, Sun J. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): an international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):75–87. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yonemori K, Shimomura A, Yasojima H, Masuda N, Aogi K, Takahashi M. A phase I/II trial of olaparib tablet formulation in combination with eribulin in Japanese patients with advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer previously treated with anthracyclines and taxanes. Eur J Cancer. 2018;109:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konstantinopoulos PA, Ceccaldi R, Shapiro GI, D’Andrea AD. Homologous recombination deficiency: exploiting the fundamental vulnerability of ovarian cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(11):1137–1154. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ono M, Tsuda H, Yunokawa M, Yonemori K, Shimizu C, Tamura K. Prognostic impact of Ki-67 labeling indices with 3 different cutoff values, histological grade, and nuclear grade in hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative, node-negative invasive breast cancers. Breast Cancer. 2015;22(2):141–152. doi: 10.1007/s12282-013-0464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allred DC, Harvey JM, Berardo M, Clark GM. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Mod Pathol. 1998;11(2):155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, Aghajanian C, Oaknin A, Dean A. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10106):1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meric-Bernstam F, Zheng X, Shariati M, Damodaran S, Wathoo C, Brusco L, et al. Survival Outcomes by TP53 mutation status in metastatic breast cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 2018;2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Kaklamani VG, Jeruss JS, Hughes E, Siziopikou K, Timms KM, Gutin A. Phase II neoadjuvant clinical trial of carboplatin and eribulin in women with triple negative early-stage breast cancer ( NCT01372579) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151(3):629–638. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3435-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman PA, Awada A, Twelves C, Yelle L, Perez EA, Velikova G. Phase III open-label randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):594–601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park YH, Im SA, Kim SB, Sohn JH, Lee KS, Chae YS. Phase II, multicentre, randomised trial of eribulin plus gemcitabine versus paclitaxel plus gemcitabine as first-line chemotherapy in patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2017;86:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hattori M, Ishiguro H, Masuda N, Yoshimura A, Ohtani S, Yasojima H. Phase I dose-finding study of eribulin and capecitabine for metastatic breast cancer: JBCRG-18 cape study. Breast Cancer. 2018;25(1):108–117. doi: 10.1007/s12282-017-0798-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yardley DA, Reeves J, Dees EC, Osborne C, Paul D, Ademuyiwa F. Ramucirumab with eribulin versus eribulin in locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with anthracycline and taxane therapy: a multicenter, randomized, Phase II study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16(6):471–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakiyama T, Tsurutani J, Iwasa T, Kawakami H, Nonagase Y, Yoshida T. A phase I dose-escalation study of eribulin and S-1 for metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(5):819–824. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pivot X, Marme F, Koenigsberg R, Guo M, Berrak E, Wolfer A. Pooled analyses of eribulin in metastatic breast cancer patients with at least one prior chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1525–1531. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Funahashi Y, Okamoto K, Adachi Y, Semba T, Uesugi M, Ozawa Y. Eribulin mesylate reduces tumor microenvironment abnormality by vascular remodeling in preclinical human breast cancer models. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(10):1334–1342. doi: 10.1111/cas.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueda S, Saeki T, Takeuchi H, Shigekawa T, Yamane T, Kuji I. In vivo imaging of eribulin-induced reoxygenation in advanced breast cancer patients: a comparison to bevacizumab. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(11):1212–1218. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kashiwagi S, Asano Y, Goto W, Takada K, Takahashi K, Hatano T. Mesenchymal-epithelial transition and tumor vascular remodeling in eribulin chemotherapy for breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(1):401–410. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kashiwagi S, Asano Y, Goto W, Takada K, Takahashi K, Noda S. Use of Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) to predict the treatment response to eribulin chemotherapy in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goto W, Kashiwagi S, Asano Y, Takada K, Morisaki T, Fujita H. Eribulin promotes antitumor immune responses in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(5):2929–2938. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papanastasiou AD, Sirinian C, Plakoula E, Zolota V, Zarkadis IK, Kalofonos HP. RANK and EGFR in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Genet. 2017;216-217:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry in the present study

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.