Abstract

Introduction

Donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) are considered an important risk factor for graft injury and failure. However, there is limited information on long-term outcomes for kidney transplant recipients with positive DSAs in the absence of rejection on biopsy.

Methods

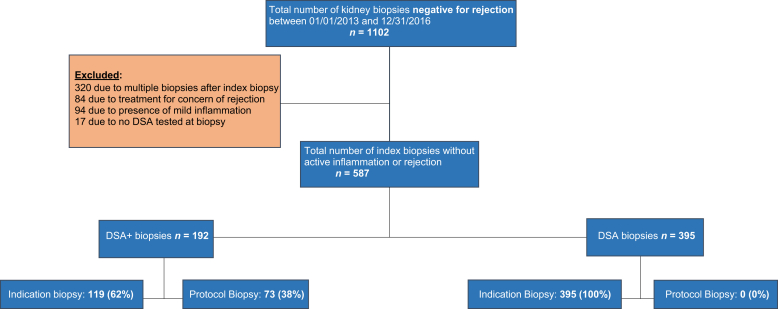

We evaluated all patients at the University of Wisconsin who underwent a kidney allograft biopsy between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2016. All patients with clinical indication or protocol biopsies that were negative for acute rejection and lacked significant acute pathological features were included in the study and divided into 2 groups based on DSAs at the time of biopsy. There were a total of 1102 kidney biopsies during the study period of which 587 fulfilled our selection criteria (DSA+, n = 192, and DSA−, n = 395). The incidence of subsequent rejection and death-censored graft failure (DCGF) were outcomes of interest.

Results

There was no difference in acute (i + t + v + c4d + ptc + g = 0 in both groups) or chronic (ci + ct + cv + cg = 2.4 ± 2.2 vs. 2.7 ± 2.4; cg = 0.12 ± 0.48 vs. 0.13 ± 0.48) Banff scores in the index biopsy. Patients were followed for a mean of 33.1 ± 16.8 months. Kaplan-Meier analyses demonstrated a higher incidence of DCGF in DSA− group (n = 83) but this was not observed for subsequent rejection (n = 76). In multivariate Cox regression analyses, the interval from transplant to biopsy, de novo DSA, and younger age remained independently associated with increased risk of subsequent rejection. Notably, there was no association between subsequent rejection or DSA (pretransplant, de novo, persistant, Class I/II, MFIsum, or MFImax) and graft failure.

Conclusion

This study suggests that in the absence of biopsy-proven rejection and acute inflammation, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DSAs are not associated with increased risk of graft failure.

Keywords: biopsies, DSA, graft survival, kidney transplant

See Commentary on Page 1040

Kidney allograft biopsy is a common procedure after transplantation, most commonly indicated by impaired allograft function or protocol biopsy for early diagnosis of pathological features.1 Allograft kidney biopsy remains the gold standard by which essential diagnostic and prognostic information is obtained after transplantation, as clinical criteria alone have been found to be inadequate for diagnosis in 50% to 70% of cases.2, 3 Clinically important pathological features include rejection, BK virus nephropathy, recurrence of primary disease, and calcineurin inhibitor toxicity.2 Studies from nearly a decade ago suggest that rejection and particularly antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) is the most common cause of graft failure.4, 5 Even in the current era of immunosuppressive medication, more than 75% of patients with chronic active ABMR lose their graft within 2 years of diagnosis.6

Anti- HLA DSAs are an important biomarker for predicting graft injury and failure.7 The presence of pretransplant DSA or the development of de novo DSA (dnDSA) is strongly associated with ABMR and graft failure.8, 9, 10 Several studies describe outcomes of patients with DSA with positive allograft findings on biopsy; however, information is limited about outcomes for patients with DSA who undergo biopsy and have a biopsy negative for rejection. Here, we hypothesize that in those with the presence of DSA, even with the absence of any significant biopsy findings, graft outcomes are inferior compared with those who had negative biopsy findings and no DSA.

Methods

Patients

We evaluated all patients at the University of Wisconsin who underwent a kidney allograft biopsy between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2016 (Figure 1). All patients with clinical indication or protocol biopsies that were negative for acute rejection based on Banff 2017 criteria and absence of any significant pathological features who did not receive active treatment were included in the study and divided into 2 groups based on DSAs at the time of biopsy. Any changes of active inflammation including tubulitis, t >0; glomerulitis, g>0; peritubular capillaritis, ptc >0; mononuclear cell interstitial inflammation, i>0; or intimal arteritis, v >0 were excluded from the study along with any c4d positivity. However, chronic changes without active findings were included. Simple dose adjustment or switching from one group of the immunosuppressive drug to another (e.g., mycophenolic acid to azathioprine or tacrolimus to cyclosporine) were neither an inclusion nor exclusion criterion. For patients with multiple kidney biopsies, we included only the first episode of biopsy during the study period (index biopsy).

Figure 1.

Study design in kidney transplant recipients without acute rejection or inflammation in transplant kidney biopsies.

Study Protocol and Data Collection

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health Institutional Review Board. Data collection included basic demographic information, date of kidney transplantation, age, race, gender, induction immunosuppression, and type of transplant. We collected the histology of kidney biopsies, DSA information, and patient and graft survival. Immunodominant DSA was defined as the DSA with maximum mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) and presented as MFImax, and the sum of DSA MFI as MFIsum. Persistent DSA was defined as DSA present at least 2 times and at least 3 months apart, including around the time of biopsy. We collected the information about subsequent biopsies and findings on subsequent biopsies for those who underwent a biopsy after index biopsy. Patient’s last follow-up was censored at death or graft failure (for those who experienced it), or at last serum creatinine for those with functioning graft.

Anti-HLA Antibody Screening by Solid-Phase Fluorescent Beads

Donor-specific HLA Class I and II antibodies were detected pre- and posttransplant using Luminex single antigen beads (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA) and performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the single modification in which a reduced volume of beads (3 vs. 5 μl) was used as reported previously.11 Briefly, antibodies were identified using multiple criteria including patterns of epitope reactivity, MFI value, specific bead behaviors, assay background, and signal to noise ratio as primary criteria, as described previously.12 DSAs were classified as de novo if they were present after transplantation but were not detected in pretransplant samples. As pretransplant antibodies did not need to meet a minimum MFI threshold to be reported, any antibody defined as “de novo” in this study is unlikely to be due to increases in weak pretransplant DSA than in studies that use MFI thresholds.

Since 2014, routine posttransplant monitoring of DSA has been performed on all transplant recipients at 6 and 12 months, and annually thereafter. Patients with a pretransplant calculated panel reactive antibody greater than 0 were tested at an additional 3-week time point, and patients with pretransplant DSA were tested at additional 3-week, 6-week, and 3-month time points. All patients undergoing transplant biopsy for any reason had DSA testing as a part of the biopsy visit.13 The yearly DSA monitoring included patients transplanted before 2014 during their annual follow-up visit.

Immunosuppression

Patients undergoing kidney transplantation received induction immunosuppression with either a depleting (anti-thymocyte globulin, alemtuzumab, or OKT3) or nondepleting (basiliximab or daclizumab) agent based on immunological risk factors. Patients with pretransplant DSA, end-stage renal disease due to glomerulonephritis, and those planned for early steroid withdrawal were more likely to receive depleting agent for induction. Patients were typically maintained on a triple immunosuppressive regimen with a calcineurin inhibitor (usually tacrolimus), antiproliferative agent (usually mycophenolate mofetil or mycophenolic acid), and steroids. Some patients had early steroid withdrawal based on clinical judgment and the patient’s request. Doses and drug levels were individually adjusted at physician discretion based on the patient’s clinical condition, including infection, malignancy, and rejection. Presence of DSA was considered for immunosuppressive tailoring, but priorities were given for other medical conditions including infections, malignancy, and the patient’s overall condition.

Kidney Allograft Biopsy

Most of the biopsies were performed for cause due to impaired graft function (rise in serum creatinine or proteinuria). Protocol biopsies were performed at months 3 and 12 for all patients with pretransplant DSAs or those who developed dnDSAs as described previously.11 Some patients underwent protocol kidney biopsy due to a significant increase in the DSAs (approximately >50% from previous MFIsum). Patients with a clinical indication for biopsy due to impaired graft function who also qualified for protocol biopsy (due to dnDSA or rise in DSA) were considered indication DSA+, as they would have undergone biopsy irrespective of the protocol. C4d staining was performed by immunoperoxidase on frozen sections.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were compared using Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate, and categorical data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Risk factors associated with rejection in subsequent biopsy and DCGF were studied using univariate and multivariate stepwise Cox regression analyses. All baseline characteristics in Table 1 and kidney function and immunopathological features in Table 2 along with some of the DSA-associated variables were used to assess the risk of rejection in subsequent biopsy or DCGF. Variables associated with outcomes at a P < 0.05 in univariate analysis were kept in the multivariate analysis. Risk of subsequent rejections and DCGF were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier analyses.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics

| Variables | DSA+ | DSA− | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 192 | 395 | |

| Female, n (%) | 81 (42) | 132 (33) | 0.04 |

| Mean age at time of Transplant, yr | 47.6 ± 13.6 | 48.9 ± 14.9 | 0.29 |

| White, n (%) | 142 (74) | 321 (81) | 0.04 |

| Causes of ESRD, n (%) | 0.41 | ||

| Glomerulonephritis | 56 (29) | 114 (29) | |

| Diabetes | 43 (22) | 87 (22) | |

| Hypertension | 22 (11) | 55 (14) | |

| PKD | 23 (12) | 46 (12) | |

| Other | 48 (25) | 93 (23) | |

| Retransplant status, n (%) | 48 (25) | 72 (18) | 0.06 |

| Living donor transplant, n (%) | 62 (32) | 168 (43) | 0.01 |

| Induction immunosuppression, n (%) | 0.10 | ||

| Basiliximab | 88 (46) | 203 (51) | |

| Anti-thymocyte globulin | 49 (26) | 71 (18) | |

| Alemtuzumab | 22 (11) | 40 (10) | |

| OKT3 | 1 (1) | 6 (2) | |

| Other/unknown | 32 (17) | 75 (19) | |

| Indication for the biopsy, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Clinically indicated | 119 (62) | 395 (100) | |

| Protocol biopsy | 73 (38)

|

0 (0) | |

dnDSA, de novo donor-specific antibodies; DSA, donor-specific antibodies; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; PKD, polycystic kidney disease.

P values that are statistically significant (P < 0.05) are in bold.

Table 2.

Baseline kidney function and immunopathology

| At baseline | Variable | DSA+ | DSA− | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSA at biopsy | Class I MFIsum | 1850 ± 3031 (n = 117) | N/A | N/A |

| Class II MFIsum | 4704 ± 6351 (n = 101) | |||

| Immunodominant MFImax | 2,999 ± 4,715 | |||

| DSA MFIsum >1000 | 107 (56%) | |||

| Patients with class I DSA only | 91 (47%) | |||

| Patients with class II DSA only | 75 (39%) | |||

| Patients with both class I & II DSA | 26 (14%) | |||

| Kidney function at biopsy | Scr (mg/dl) | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 0.08 |

| eGFR (ml/min) | 44.7 ± 22.2 | 37.1 ± 19.6 | <0.001 | |

| UPC (g/g) | 0.18 ± 0.39 | 0.32 ± 0.47 | <0.001 | |

| Banff pathology | i (0–3) | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| t (0–3) | 0 | 0 | N/A | |

| v (0–3) | 0 | 0 | N/A | |

| g (0–3) | 0 | 0 | N/A | |

| ptc (0–3) | 0 | 0 | N/A | |

| c4d (0–3) | 0 | 0 | N/A | |

| cg (0–3) | 0.12 ± 0.48 | 0.13 ± 0.48 | 0.88 | |

| cg>0 | 14 (7%) | 31 (8%) | 0.81 | |

| ci+ct+cg+cv (0–12) | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 2.7 ± 2.4 | 0.16 |

Banff pathology: i, mononuclear cell interstitial inflammation; t, tubulitis; v, intimal arteritis; g, glomerulitis; ptc, peritubular capillaritis.

DSA, donor-specific antibodies; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; N/A, not applicable; Scr, serum creatinine; UPC, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio.

P values that are statistically significant (P < 0.05) are in bold.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 587 patients fulfilled our selection criteria, of whom 192 (33%) were in the DSA+ group and 395 (67%) in the DSA− group (Table 1). The DSA+ group included fewer male, white, and live donor transplant recipients and more protocol biopsies (P < 0.05 for all). Prior kidney transplant recipients were more common in the DSA+ group, although did not meet statistical significance 25% versus 18% (P = 0.06). There were 73 (38%) protocol biopsies in the DSA+ group, due to pretransplant DSA (n = 33.17%), dnDSA (n = 29.15%), or a 50% rise in DSA (n = 11.6%). All biopsies in the DSA− group were clinically indicated due to rise in serum creatinine or proteinuria. All other baseline characteristics were similar between the 2 groups. The median interval from transplant to index biopsy was 12.3 months, ranging from 0.13 to 337 months.

Immunopathology and Kidney Function

There were 120 (63%) patients in the DSA+ group with class I DSA and 101 (53%) with class II DSA (Table 2). A total of 107 (56%) patients had a sum MFI greater than 1000 at the time of biopsy. Renal function was significantly better in the DSA+ group at the time of biopsy with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 44.7 ± 22.2 ml/min per 1.72 m2 compared with the 37.1 ± 19.6 in the DSA− group (P < 0.001). Due to our strict selection criteria, renal biopsies had no acute inflammation; therefore, i, t, v, g, ptc, and c4d scores were all 0 in both groups. Transplant glomerulopathy (mean score or percent of patients with cg) was not different between the 2 groups. Likewise, sum chronicity scores (2.4 ± 2.2 vs. 2.7 ± 2.4) were similar between the 2 groups (P = 0.16).

Variables Associated With Subsequent Rejection

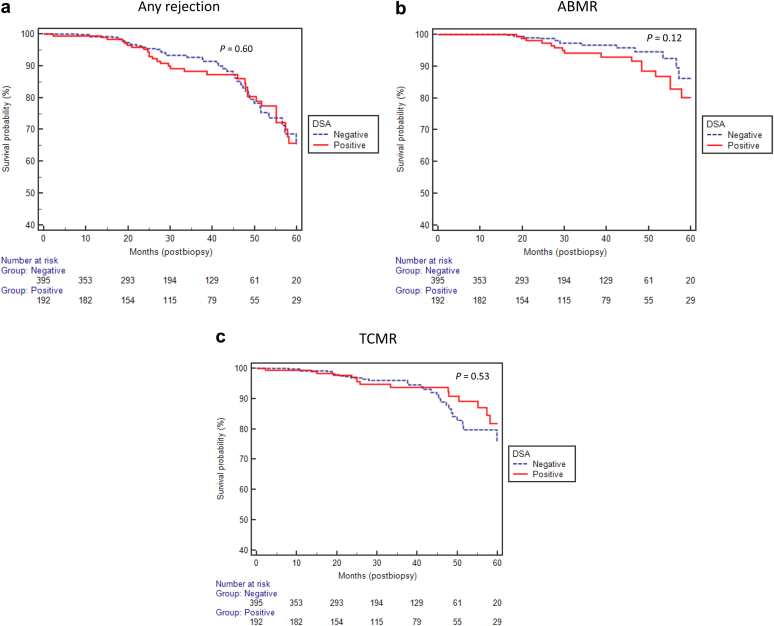

During the observation period of 33.1 ± 16.8 months (median 31.0 months, range: 0.1–66.1 months), a total of 214 (36%) patients (90 vs.124 in DSA+ and DSA− groups, respectively, P < 0.0001) underwent subsequent biopsies for suspicion of rejection. Of these, 76 (36%) had biopsy findings consistent with rejection (34 vs. 42 in DSA+ and DSA− groups, respectively, P = 0.6, Figure 2a). There was no difference in the incidence of ABMR or T-cell–mediated rejection between the groups (Figure 2b and c). When categorized based on the MFI, there were 51 patients with MFI <500, 34 with MFI 500 to 1000, 27 with MFI >1000 to 2000, and 80 with MFI >2000 at time of biopsy. There was no difference in the risk of subsequent rejection in this subgroup compared with the DSA− group (P = 0.52) (figure not shown).

Figure 2.

(a,b,c) No significant difference in the risk of rejection on subsequent biopsies between donor-specific antibody (DSA)+ and DSA− groups. ABMR, antibody-mediated rejection; TCMR, T-cell–mediated rejection.

In univariate Cox regression analyses, 4 variables were independently associated with subsequent rejection: interval from transplant to index biopsy (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.99; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.98–1.0; P = 0.01), dnDSA (HR: 2.33; 95% CI: 1.22–4.45; P = 0.009), age (HR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.96–0.99; P = 0.007), and sum chronicity score (HR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.76–0.98; P = 0.027) (Table 3). In a multivariable model including interval from transplant to index biopsy, dnDSA, age, and sum chronicity score, the following remained independently associated with rejection: dnDSA (HR: 2.04; 95% CI: 1.07–3.92; P = 0.03), age (HR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.96–0.99; P = 0.003), and interval from transplant to the biopsy (HR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.98–1.0; P = 0.02). Most of the patients with dnDSA underwent protocol biopsy, but we believe dnDSA associated with subsequent rejection was not simply detection bias. In patients with dnDSA and negative index biopsy findings, we do not routinely repeat biopsy unless clinically indicated.

Table 3.

Risk factors associated with subsequent rejection

| Variables | Univariate analyses |

Multivariable analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P | 95% CI | HR | P | 95% CI | |

| Female | 0.89 | 0.65 | 0.56–1.44 | |||

| Age/yr | 0.98 | 0.007 | 0.96–0.99 | 0.97 | 0.003 | 0.96–0.99 |

| White | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.55–1.58 | |||

| Diabetes as a cause of ESRD | 0.59 | 0.10 | 0.31–1.11 | |||

| Repeat transplant | 0.87 | 0.64 | 0.48–1.55 | |||

| Living donor | 0.79 | 0.32 | 0.49–1.26 | |||

| Depleting induction | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.57–1.46 | |||

| Clinically indicated biopsy | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.52–1.74 | |||

| Any DSA (yes/no) | 1.12 | 0.60 | 0.71–1.78 | |||

| Interval from transplant to the index biopsy (per month) | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.98–1.0 | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.98–1.0 |

| dnDSA | 2.33 | 0.009 | 1.22–4.45 | 2.04 | 0.03 | 1.07–3.92 |

| Pretransplant DSA | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.45–1.65 | |||

| Persistent DSA | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0.43–1.51 | |||

| Class II DSA | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.41–1.67 | |||

| DSA MFIsum > 1000 | 1.15 | 0.59 | 0.68–1.94 | |||

| Immunodominant DSA >1000 | 1.21 | 0.46 | 0.72–2.05 | |||

| DP DSA | 0.95 | 0.99 | 1.93–6.58 | |||

| DQ DSA | 1.52 | 0.15 | 0.86–2.67 | |||

| DR DSA | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.15–1.49 | |||

| eGFR at time of biopsy | 0.99 | 0.51 | 0.98–1.0 | |||

| UPC at time of biopsy | 0.83 | 0.54 | 0.47–1.47 | |||

| cg score > 0 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.04–2.19 | |||

| Sum chronicity score | 0.86 | 0.027 | 0.76–0.98 | 0.91 | 0.18 | 0.80–1.04 |

CI, confidence interval; dnDSA, de novo donor-specific antibodies; DSA, donor-specific antibodies; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HR, hazard ratio; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; UPC, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio.

P values that are statistically significant (P < 0.05) are in bold.

Likewise, 38 (10%) patients in the DSA− group developed DSA during the study period, of whom 16 (4%) had rejection on the subsequent biopsy (9 ABMR and 7 ACR). Of note, none of these patients, or any patients in DSA+ group had significant immunosuppressive medication adjustment after index biopsy.

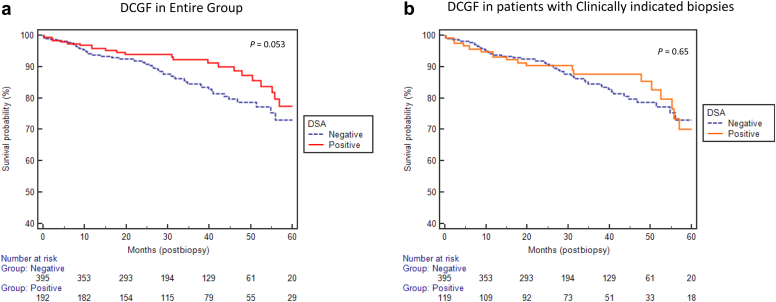

Variables Associated With DCGF

There were a total of 83 DCGF, 23 (12%) in the DSA+ group and 60 (15%) in the DSA− group (P = 0.053, Figure 3a). The incidence of DCGF was not different between patients who underwent clinically indicated biopsies in both groups (Figure 3b). Similarly, the incidence of graft failure was not different in patients without transplant glomerulopathy (cg = 0, P = 0.41, data not shown). Likewise, the incidence of DCGF was not statistically different when subdividing DSA MFI into different categories of <500, 500–1000, >1000–2000, and >2000 (P = 0.07, data not shown).

Figure 3.

(a,b) No difference in death-censored graft failure (DCGF) between donor-specific antibody (DSA)+ and DSA− groups even after removing protocol biopsy in the DSA+ group.

In univariate analyses, age (HR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.97–0.99; P = 0.04), interval from transplant to index biopsy (HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 1.0–1.01; P ≤ 0.001), clinically indicated biopsy (HR: 4.61; 95% CI: 1.45–14.64; P = 0.009), eGFR (HR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.95–0.97; P < 0.001), proteinuria (HR: 3.44; 95% CI: 2.23–5.30; P < 0.001), cg (HR: 4.02; 95% CI: 2.28–7.07; P < 0.001), and sum chronicity score (HR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.29–1.52; P < 0.001) were associated with graft failure (Table 4). In the multivariable model including all these 7 variables, however, only interval from transplant to the biopsy (HR: 1.004; 95% CI: 1.0–1.01; P = 0.003), eGFR (HR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.95–0.98; P < 0.001), proteinuria (HR: 2.01; 95% CI: 1.32–3.29; P = 0.002), and sum chronicity score (HR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.09–1.34; P < 0.001) were retained as independently associated with the graft failure. Notably, subsequent rejection was not associated with graft failure.

Table 4.

Risk factors associated with death-censored graft failure

| Variables | Univariate analyses |

Multivariable analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P | 95% CI | HR | P | 95% CI | |

| Female | 0.96 | 0.87 | 0.61–1.50 | |||

| Age/yr | 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.97–0.99 | 0.98 | 0.21 | 0.97–1.0 |

| White | 1.65 | 0.10 | 0.89–3.05 | |||

| Diabetes as a cause of ESRD | 1.31 | 0.27 | 0.80–2.11 | |||

| Repeat transplant | 1.07 | 0.80 | 0.63–1.80 | |||

| Living donor | 0.84 | 0.44 | 0.54–1.31 | |||

| Depleting induction | 0.71 | 0.16 | 0.44–1.14 | |||

| Clinically indicated biopsy | 4.61 | 0.009 | 1.46–14.64 | 1.99 | 0.27 | 0.57–6.89 |

| Any DSA (yes/no) | 0.62 | 0.06 | 0.38–1.01 | |||

| Interval from transplant to the index biopsy (per month) | 1.01 | <0.001 | 1.0–1.01 | 1.004 | 0.003 | 1.0–1.01 |

| dnDSA | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.40–2.13 | |||

| Pretransplant DSA | 1.0 | 0.95 | 1.9–8.67 | |||

| Persistent DSA | 1.30 | 0.33 | 0.76–2.23 | |||

| Class II DSA | 0.78 | 0.56 | 0.34–1.77 | |||

| DSA MFIsum > 1000 | 0.84 | 0.55 | 0.48–1.47 | |||

| Immunodominant DSA >1000 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.51–1.56 | |||

| DP DSA | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.07–3.7 | |||

| DQ DSA | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.33–1.43 | |||

| DR DSA | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.15–1.59 | |||

| eGFR at time of biopsy | 0.96 | <0.001 | 0.95–0.97 | 0.96 | <0.001 | 0.95–0.98 |

| UPC at time of biopsy | 3.44 | <0.001 | 2.23–5.30 | 2.01 | 0.002 | 1.32–3.29 |

| cg score > 0 | 4.02 | <0.001 | 2.28–7.07 | 1.39 | 0.34 | 0.71–2.73 |

| Sum chronicity score | 1.40 | <0.001 | 1.29–1.52 | 1.21 | <0.001 | 1.09–1.34 |

| Subsequent acute rejection | 1.55 | 0.10 | 0.91–2.65 | |||

CI, confidence interval; dnDSA, de novo donor-specific antibodies; DSA, donor-specific antibodies; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HR, hazard ratio; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; UPC, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio.

P values that are statistically significant (P < 0.05) are in bold.

At last follow-up (33.1 ± 16.8 months after index biopsy), mean eGFR was not significantly different between groups (48.7 ± 20.5 in DSA+ vs. 46.8 ± 17.8 ml/min per 1.72 m2 in DSA− group, P = 0.32).

Discussion

We observed that kidney transplant recipients with HLA DSA had similar outcomes as patients without DSA if index biopsy findings were negative for active ABMR, T-cell–mediated rejection, and inflammation. Specifically, we observed no difference in the incidence of subsequent rejection or graft failure between the 2 groups. Furthermore, we found no independent association between DSA (pretransplant, de novo, persistant, Class I/II, MFIsum, or MFImax) and graft failure. In aggregate, our findings suggest that in the absence of biopsy-proven rejection and acute inflammation, HLA DSAs are not associated with increased risk of graft failure.

The presence of DSA has been associated with increased risk of ABMR and is an important biomarker for predicting graft injury and failure.7 The incidence of ABMR has been shown to be up to 9-fold higher in patients with preformed DSA compared with patients without DSA, and results in worse graft outcomes.14 Detection of dnDSA is considered a marker and contributor of ongoing alloimmunity; this is evidenced by an increased rate of decline in eGFR even before the detection of dnDSA, followed by an accelerated decline in eGFR after detection of dnDSA.15 Several studies have even suggested dnDSA as a prognostic biomarker for predicting poor graft survival.16, 17, 18, 19

However, not all recipients with HLA DSA develop evidence of graft damage on kidney allograft biopsy, as we have demonstrated in this study and confirmed what many have seen in clinical practice. These findings add further evidence that the biological relevance of DSA remains poorly defined.8, 20 Studies evaluating complement binding of DSA as measured by C1q fixation and C3d-binding activity, and assessing the presence of intragraft dnDSA homings have attempted to address this question.21, 22, 23 Nocera et al.21 demonstrated that in the presence of circulating DSAs, intragraft DSAs were demonstrated in 72% of biopsy specimens. A significantly higher homing capability was expressed by class II DSAs. However, in patients with positive serum DSAs, intragraft DSAs did not allow stratification for antibody-mediated lesions and graft loss.21 As a result, it is still not clear why some patients with DSAs develop active or chronic active ABMR and lose their allograft, whereas others maintain a stable graft function and have a normal biopsy. Collectively, these data seem to suggest that some DSAs may in fact be benign, but further study and longer follow-up are needed to support such a conclusion.

In 2 recent studies, Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0-ST arrays were used to assess the gene expression profiles of patients with kidney transplant who presented with DSA but showed normal biopsy histopathology and did not develop ABMR.24, 25 Biopsy and whole-blood profiles for DSA+/ABMR− patients were compared with both DSA+/ABMR+ patients as well as DSA− controls. Gene-set enrichment analysis using previously identified pathogenesis-based transcripts identified a clear molecular signature involving increased rejection-associated transcripts in ABMR− patients.24 In the second study, regulatory T-cell transcripts were upregulated in DSA+/ABMR+ patients, whereas B-cell transcripts were upregulated in DSA+/ABMR− patients.25 Patients in the latter group had increased rejection-associated gene transcripts in their allografts but not in their blood, whereas DSA+/ABMR+ patients had increased rejection-associated gene transcripts in both allografts and blood samples.25 Consistent with these findings, our data suggest that in the absence of biopsy-proven rejection, DSAs may be associated with subsequent rejection, but not graft survival. Although these 2 studies determined “persistent” DSA to be associated with subsequent rejection in 4 (16%) of 25 DSA+/ABMR− patients,24, 25 we found de novo DSAs that persisted after index biopsy to predict future rejection episodes in 18% of the cohort. Notably, these events were not associated with graft failure at last follow-up. The underlying mechanisms for this observation remain unclear, it is possible that increased levels of rejection-associated transcripts, including those related to interferon gamma, T-cells, B-cells, natural killer cells, and macrophages characterize molecular rejection in the absence of pathology.24, 25 There were some similarities and differences between our and 2 prior published studies on this topic.24, 25 First, we had significantly larger sample size of 192 in the DSA+ group compared with 25 in their study. Similar to prior studies, we had DCGF of 12%, with similar post index biopsy follow-up time. In addition, at last follow-up among patients with functional graft, graft function was similar between DSA+ and DSA− groups. Interestingly, in their study, none of the patients in the DSA− group had subsequent rejection during the study period, compared with 42 (11%) of 395 in our study. In contrast to their study, our study was mainly clinically oriented and was focused on the clinical outcomes, including risk of rejections, association of DSA, MFI, and so forth.

Our study has the inherent limitations of a single-center retrospective study, reflecting our specific population and clinical approach. Gene transcripts/classifiers in the biopsy tissue are not commonly used at our institution and were not used in any of our patients. Also, we had relatively shorter post-biopsy follow-up (less than 3 years), which may not translate into significant outcomes. However, our findings have practical implications for transplant providers regarding the biological relevance of circulating DSAs in the absence of rejection, without minimizing the value of DSA monitoring.13, 26 More studies are needed to determine the optimal strategy to monitor patients with positive DSAs in the absence of rejection, including defining the role of molecular diagnostics, donor-derived cell-free DNA, eplet-based DSA diagnostics,27 and surveillance biopsies.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Ms. Dana Clark, MA, for her editorial assistance.

Author Contributions

SP: concept, design, data collection, analysis, manuscript preparation, editing; EJ, SA, FA, and JB: data collection, analysis, manuscript preparation, editing; NG, BM, MM, RRR, DAM, and WZ: analysis, manuscript preparation, editing; and AD: concept, design, analysis, manuscript preparation, editing.

Footnotes

STROBE statement.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Ahmad I. Biopsy of the transplanted kidney. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2004;21:275–281. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-861562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams W.W., Taheri D., Tolkoff-Rubin N., Colvin R.B. Clinical role of the renal transplant biopsy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:110–121. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redfield R.R., McCune K.R., Rao A. Nature, timing, and severity of complications from ultrasound-guided percutaneous renal transplant biopsy. Transpl Int. 2016;29:167–172. doi: 10.1111/tri.12660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sellares J., de Freitas D.G., Mengel M. Understanding the causes of kidney transplant failure: the dominant role of antibody-mediated rejection and nonadherence. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:388–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Zoghby Z.M., Stegall M.D., Lager D.J. Identifying specific causes of kidney allograft loss. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redfield R.R., Ellis T.M., Zhong W. Current outcomes of chronic active antibody mediated rejection: a large single center retrospective review using the updated BANFF 2013 criteria. Hum Immunol. 2016;77:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2016.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viglietti D., Loupy A., Vernerey D. Value of donor-specific anti-HLA antibody monitoring and characterization for risk stratification of kidney allograft loss. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:702–715. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohan S., Palanisamy A., Tsapepas D. Donor-specific antibodies adversely affect kidney allograft outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:2061–2071. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willicombe M., Brookes P., Sergeant R. De novo DQ donor-specific antibodies are associated with a significant risk of antibody-mediated rejection and transplant glomerulopathy. Transplantation. 2012;94:172–177. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182543950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terasaki P.I., Ozawa M., Castro R. Four-year follow-up of a prospective trial of HLA and MICA antibodies on kidney graft survival. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:408–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parajuli S., Mandelbrot D.A., Muth B. Rituximab and monitoring strategies for late antibody-mediated rejection after kidney transplantation. Transplant Direct. 2017;3:e227. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis T.M. Interpretation of HLA single antigen bead assays. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2013;27:108–111. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parajuli S., Reville P.K., Ellis T.M. Utility of protocol kidney biopsies for de novo donor-specific antibodies. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:3210–3218. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefaucheur C., Suberbielle-Boissel C., Hill G.S. Clinical relevance of preformed HLA donor-specific antibodies in kidney transplantation. Contrib Nephrol. 2009;162:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000170788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiebe C., Gibson I.W., Blydt-Hansen T.D. Rates and determinants of progression to graft failure in kidney allograft recipients with de novo donor-specific antibody. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2921–2930. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizutani K., Terasaki P., Rosen A. Serial ten-year follow-up of HLA and MICA antibody production prior to kidney graft failure. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2265–2272. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terasaki P.I. Humoral theory of transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:665–673. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee P.C., Terasaki P.I., Takemoto S.K. All chronic rejection failures of kidney transplants were preceded by the development of HLA antibodies. Transplantation. 2002;74:1192–1194. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200210270-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Everly M.J., Rebellato L.M., Haisch C.E. Incidence and impact of de novo donor-specific alloantibody in primary renal allografts. Transplantation. 2013;95:410–417. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31827d62e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loupy A., Vernerey D., Tinel C. subclinical rejection phenotypes at 1 year post-transplant and outcome of kidney allografts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1721–1731. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014040399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nocera A., Tagliamacco A., Cioni M. Kidney intragraft homing of de novo donor-specific HLA antibodies is an essential step of antibody-mediated damage but not per se predictive of graft loss. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:692–702. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sicard A., Ducreux S., Rabeyrin M. Detection of C3d-binding donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies at diagnosis of humoral rejection predicts renal graft loss. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:457–467. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loupy A., Lefaucheur C., Vernerey D. Complement-binding anti-HLA antibodies and kidney-allograft survival. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1215–1226. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ó Broin P., Hayde N., Bao Y. A pathogenesis-based transcript signature in donor-specific antibody-positive kidney transplant patients with normal biopsies. Genom Data. 2014;2:357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayde N., Broin P.O., Bao Y. Increased intragraft rejection-associated gene transcripts in patients with donor-specific antibodies and normal biopsies. Kidney Int. 2014;86:600–609. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orandi B.J., Chow E.H., Hsu A. Quantifying renal allograft loss following early antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:489–498. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiebe C., Rush D.N., Nevins T.E. Class II eplet mismatch modulates tacrolimus trough levels required to prevent donor-specific antibody development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3353–3362. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.