Abstract

Background

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a fundamental contributor to health; however, limited research has examined sexual orientation differences in SES.

Methods

2008–2009 data from 14 051 participants (ages 24–32 years) in the US-based, representative, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health were analysed using multivariable regressions that adjusted for age, race-ethnicity, childhood SES, urbanicity and Census region, separately for females and males. Modification by racial minority status (black or Latino vs white, non-Hispanic) was also explored.

Results

Among females, sexual minorities (SM) (10.5% of females) were less likely to graduate college, and were more likely to be unemployed, poor/near poor, to receive public assistance and to report economic hardship and lower social status than heterosexuals. Adjusting for education attenuated many of these differences. Among males, SM (4.2% of males) were more likely than heterosexuals to be college graduates; however, they also had lower personal incomes. Lower rates of homeownership were observed among SM, particularly racial minority SM females. For males, household poverty patterns differed by race-ethnicity: among racial minority males, SM were more likely than heterosexuals to be living at >400% federal poverty level), whereas the pattern was reversed among whites.

Conclusions

Sexual minorities, especially females, are of lower SES than their heterosexual counterparts. SES should be considered a potential mediator of SM stigma on health. Studies of public policies that may produce, as well as mitigate, observed SES inequities, are warranted.

BACKGROUND

Health inequalities by sexual orientation have been widely documented in every domain of health,1–4 including: violence victimisation,5–9 tobacco use,10,11 suicidality,12–15 poor mental health16–19 and healthcare barriers.20 HIV/AIDS has exacted a prolonged toll on gay and bisexual men.21,22 Obesity23,24 and disability,2,25 have, more recently, emerged as lesbian health concerns.

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a fundamental contributor to health and disease across the life course,26–28 and varies by sexual orientation; however, SES is often treated as a statistical control and is rarely discussed as a potential mediator of health inequities experienced by sexual minorities (SM). Inadequate economic resources are associated with poor health28–32 through both material and psychosocial pathways that increase exposure to hazards and decrease exposure to health-promoting resources.26,33 Consistent with a socioeconomic gradient in health, several,25,34,35 but not all,2 population-based studies report higher rates of poverty among SM compared with heterosexuals. Yet, these findings vary by sex,25,34 sexual orientation,25,34,35 selection of statistical controls34 and place.2,25,35 For instance, nationally, higher poverty rates were found among female same-sex couples than among married different-sex couples, whereas, among males, poverty rates were lower among same-sex couples.34 However, after adjusting for education, employment and demographic characteristics, poverty rates were higher for same-sex male couples compared with married different-sex couples.34

In addition to variability in findings that used income-based measures of economic status, peer-reviewed research has yet to examine sexual orientation differences in assets, financial hardship and subjective social status—aspects of SES that have been linked to health in general population samples.28,30,36–38 Understanding the breadth and nature of sexual orientation differences in SES is essential to reducing health inequities, particularly as the size of the SM population grows39 and ages. The current study addresses these gaps in knowledge and examines a comprehensive array of SES indicators across sexual orientation groups, separately by sex, in a large, population-based sample.

METHODS

Sample

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) is a nationally representative, longitudinal study of US adolescents initiated in 1994 and conducted by the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina. In the 1994–1995 academic year, a total of 20 745 adolescents enrolled in grades 7–12 completed baseline in-home surveys. Add Health, whose methods have been well-described elsewhere,40 is currently in the field with the wave V survey. The current study focused on outcomes measured in the young adulthood/wave IV survey, conducted in 2008–2009 when respondents were aged 24–34 years. Eligibility for the current cross-sectional study was limited to those who completed baseline and wave IV surveys (n=15 701; 80.3% of original baseline sample) and for whom a wave IV sampling survey weight was available (n=14 800). Missingness due to the lack of a Wave I sampling weight was administrative in nature,41 and thus, was ignorable42 in relation to the analyses presented in this manuscript. The final analytic sample included 14 051 respondents (93.7% weighted, of those eligible) who provided data on sexual orientation and covariates.

Measures

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation identity was embedded in the computer-assisted self-interviewing portion of the interview which has been shown to increase disclosure of ‘sensitive’ subject matter.43 Respondents who selected bisexual, mostly homosexual or 100% homosexual options as their sexual orientation identity at wave IV were classified as SM while those who selected 100% heterosexual were classified as heterosexual. Self-reported mostly heterosexuals (n=1368) were classified as sexual minorities if they reported one or more lifetime same-sex sexual partners (n=528); otherwise, they were grouped with heterosexuals (n=840).

Prior to grouping all SM, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine whether bisexually identified individuals should be grouped with other SM (vs treated separately) given that bisexuals in Washington state and Massachusetts25,35 were found to have the lowest SES of all sexual orientation groups. In multivariable regressions, we observed that the pattern (direction and magnitude of associations between sexual orientation and SES indicators) was similar in models that included and excluded bisexuals (n=214). Consequently, we created one SM group.

Sex

Respondents were classified as male or female based on their responses to a wave I question, “What is your sex?”

Wave IV SES

Educational attainment was parameterised as <high school (HS)/ graduate equivalence degree (GED), HS/GED, some college or vocational education and ≥bachelor’s degree. Wave IV employment status was coded as currently employed (10 or more hours per week for pay), unemployed, homemaker, student and other (not employed due to disability, temporary parental leave, activity military service or incarceration). Personal income in the prior year, before taxes and deductions and including non-legal sources, was categorised as <US$10 000, US$10 000–US$24 999, US$25 000–US$49 999 and ≥US$50 000. Respondent-reported annual household income and size were used to create an ordinal measure of percentage poverty. Annual household income, also collected categorically, was recoded to the mid-point for each income range or, for those who selected the highest category (≥US$150 000), to the 95% percentile of 2007 annual family income (US$197 216).44 Recoded income was divided by size-specific poverty thresholds45 to obtain percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL) (ie, the ‘income-to-needs ratio’).46

Receipt of public assistance in adulthood was indicated if the respondent, or anyone in their household, had received public assistance, welfare payments or food stamps since their last interview in 1995 (wave II) or 2001–2002 (wave III). Economic hardship in the prior 12 months was indicated by endorsement of any of six indicators, created for Add Health, unless otherwise noted. These were: went without phone service, did not pay full amount of the rent or mortgage, did not pay full gas, electricity or oil bill, evicted from house or apartment, had gas/electricity/oil utility service shut off or were worried whether food would run out before being able to buy more because they did not have enough money.47 Current homeownership was indicated by a yes to the question, “Is your house, apartment, or residence owned or being bought by (YOU AND/OR YOUR SPOUSE/PARTNER)?” The MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status SES Ladder48 was used to assess subjective social status. Respondents were asked to indicate where they fell on a ladder from 1 to 10 (1 being ‘the people who have the least money and education, and the least respected jobs or no job’) relative to other people in the USA.

Covariates

A number of self-reported sociodemographic characteristics, associated with both sexual orientation and SES, were treated as potential confounders. These included: age (24–27, 28–29, 30–34 years) and wave I race-ethnicity, which was coded hierarchically as any Hispanic ethnicity, black, Asian or Pacific Islander or American Indian or self-reported ‘other’ race and white. Parental education at wave I was defined as the highest attainment obtained by a parent/guardian (less than a HS diploma, HS or GED, some college, vocational school or post-HS training, >bachelor’s degree) as reported by the respondent or the parent/guardian. Receipt of public assistance in childhood was indicated if anyone in the household received ‘public assistance, welfare payments or food stamps’ before the respondent was 18. Data were collected at wave III or at wave IV if wave III data were missing. Wave IV Census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West and wave IV urbanicity were based on the respondent’s Census tract. Census tracts with density below 1000 people/square mile, as per 2009 American Community Survey 5-year estimates, were characterised as rural49; all others were categorised as urban.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to compare the distribution of SES indicators and covariates across sexual orientation groups separately by sex (table 1). Sex-stratified multinomial and binary logistic regression models were fit for each SES indicator to generate relative risk ratios (probability ratios) or ORs, respectively, using the following model-building approach: a) crude (model 1 as shown in table 2); b) adjusted for covariates (age, race-ethnicity, highest parental education, receipt of public assistance <age 18 years, urbanicity and Census region (model 2), c) adjusted for education plus all covariates (model 3) and d) adjusted for employment status, education, plus all covariates (model 4). This model-building approach allowed us to examine associations between sexual orientation and SES, with and without adjustment for education and employment status. In order to provide information about the SES distribution of each sexual orientation group, adjusting for potential confounders, but not accounting for factors on the casual pathway (ie, education and employment status), predicted probabilities (categorical outcomes) and average values (continuous outcome) for each SES indicator were computed separately by sexual orientation using the margins command in STATA, following model 2 and reported in table 3.

Table 1.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of wave IV National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Young Adult Health participants (n=14 051) by sexual orientation and sex

| Females (n=7518) | Males (n=6533) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Heterosexual (n=6757) | Sexual minority (n=761) | All | Heterosexual (n=6238) | Sexual minority (n=295) | P values | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | P values | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Demographics | ||||||||||||||

| Age (years), wave IV | ||||||||||||||

| 24–27 | 2428 | 38.2 | 2134 | 37.5 | 294 | 43.9 | <0.001 | 1816 | 34.4 | 1737 | 34.5 | 79 | 32.0 | 0.85 |

| 28–29 | 2810 | 34.3 | 2516 | 33.9 | 294 | 37.7 | 2460 | 33.4 | 2340 | 33.4 | 120 | 34.6 | ||

| 30–34 | 2280 | 27.5 | 2107 | 28.6 | 173 | 18.4 | 2257 | 32.2 | 2161 | 32.1 | 96 | 33.4 | ||

| Race-ethnicity, wave IV* | ||||||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 3994 | 66.5 | 3559 | 66.2 | 435 | 69.6 | 0.27 | 3573 | 66.6 | 3420 | 66.7 | 153 | 64.6 | 0.15 |

| Hispanic | 1182 | 11.4 | 1077 | 11.4 | 105 | 11.4 | 1057 | 12.0 | 992 | 11.8 | 65 | 17.3 | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1717 | 16.0 | 1553 | 16.4 | 164 | 12.5 | 1264 | 14.7 | 1211 | 14.8 | 53 | 12.4 | ||

| Other, non-Hispanic | 625 | 6.1 | 568 | 6.0 | 57 | 6.5 | 639 | 6.7 | 615 | 6.8 | 24 | 5.7 | ||

| Parental education, wav | e I | |||||||||||||

| <HS diploma | 984 | 12.0 | 894 | 12.0 | 90 | 12.2 | 0.84 | 764 | 11.9 | 725 | 11.8 | 39 | 14.1 | 0.09 |

| HS diploma/GED | 1936 | 28.0 | 1734 | 28.0 | 202 | 28.3 | 1598 | 26.5 | 1519 | 26.5 | 79 | 25.4 | ||

| Some college or vocational school | 2155 | 29.3 | 1933 | 29.1 | 222 | 30.8 | 1949 | 30.4 | 1878 | 30.8 | 71 | 21.9 | ||

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 2443 | 30.7 | 2196 | 30.9 | 247 | 28.7 | 2222 | 31.2 | 2116 | 30.8 | 106 | 38.6 | ||

| Number of household members, including respondent (mean) | 3.34 | 3.35 | 3.24 | 0.21 | 3.06 | 3.08 | 2.57 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Received household assistance before age 18 years, wave III or IV | 1413 | 18.6 | 1220 | 17.8 | 193 | 26.1 | <0.001 | 1073 | 17.1 | 1016 | 17.1 | 57 | 17.9 | 0.31 |

| Urbanicity, wave IV† | ||||||||||||||

| Rural | 3871 | 57.3 | 3517 | 57.7 | 354 | 53.8 | 0.17 | 3327 | 55.1 | 3214 | 55.6 | 113 | 43.9 | 0.013 |

| Urban | 3647 | 42.7 | 3240 | 42.3 | 407 | 46.2 | 3206 | 44.9 | 3024 | 44.4 | 182 | 56.1 | ||

| Geographic region, wav | e IV | |||||||||||||

| Northeast | 957 | 13.0 | 863 | 13.0 | 94 | 12.9 | 0.40 | 766 | 12.8 | 717 | 12.5 | 49 | 17.9 | 0.25 |

| Midwest | 1726 | 29.2 | 1536 | 29.1 | 190 | 30.2 | 1504 | 27.6 | 1450 | 27.5 | 54 | 28.3 | ||

| South | 3065 | 40.6 | 2775 | 41.0 | 290 | 37.3 | 2662 | 42.0 | 2544 | 42.3 | 118 | 35.6 | ||

| West | 1770 | 17.2 | 1583 | 16.9 | 187 | 19.7 | 1601 | 17.7 | 1527 | 17.7 | 74 | 18.3 | ||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||||||||||

| Educational attainment | ||||||||||||||

| <HS diploma or GED | 437 | 7.1 | 363 | 6.5 | 74 | 12.5 | <0.001 | 574 | 9.7 | 553 | 9.8 | 21 | 7.6 | 0.004 |

| HS diploma or GED | 985 | 13.6 | 884 | 13.5 | 101 | 14.7 | 1225 | 21.2 | 1194 | 21.7 | 31 | 10.5 | ||

| Some college or vocational education | 3345 | 44.4 | 2942 | 43.7 | 403 | 51.0 | 2863 | 41.4 | 2733 | 41.3 | 130 | 44.3 | ||

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 2751 | 34.8 | 2568 | 36.3 | 183 | 21.8 | 1871 | 27.6 | 1758 | 27.2 | 113 | 37.6 | ||

| Wave IV employment statust‡ | ||||||||||||||

| Employed | 5829 | 76.7 | 5282 | 77.4 | 547 | 70.2 | 0.002 | 5589 | 84.8 | 5333 | 84.9 | 256 | 84.6 | 0.04 |

| Unemployed | 417 | 5.5 | 343 | 5.1 | 74 | 9.4 | 454 | 7.0 | 439 | 7.1 | 15 | 5.5 | ||

| Homemaker | 686 | 9.9 | 616 | 9.7 | 70 | 11.2 | 18 | 0.2 | 16 | 0.2 | § | § | ||

| Student | 248 | 3.5 | 223 | 3.5 | 25 | 3.4 | 145 | 2.1 | 136 | 2.1 | 9 | 3.9 | ||

| Other | 338 | 4.4 | 293 | 4.2 | 45 | 5.8 | 327 | 5.8 | 314 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 13 | ||

| Personal income | ||||||||||||||

| <US$10000 | 1663 | 24.1 | 1478 | 23.9 | 185 | 26.1 | <0.001 | 685 | 11.5 | 651 | 11.3 | 44 | 16.3 | 0.04 |

| US$10000–US$24999 | 1781 | 25.0 | 1536 | 24.1 | 245 | 32.6 | 1147 | 18.6 | 1081 | 18.4 | 66 | 24.0 | ||

| US$25 000–US$49 999 | 2814 | 37.5 | 2585 | 38.3 | 229 | 29.9 | 2688 | 41.3 | 2566 | 41.4 | 122 | 39.0 | ||

| ≥US$50 000 | 1109 | 13.4 | 1018 | 13.7 | 91 | 11.4 | 1881 | 28.6 | 1824 | 28.9 | 57 | 20.7 | ||

| Poverty-to-income needs ratio | ||||||||||||||

| <100% | 834 | 13.0 | 732 | 12.8 | 102 | 14.1 | 0.04 | 457 | 8.5 | 427 | 8.4 | 30 | 10.8 | 0.75 |

| 100%—199% | 1097 | 15.3 | 949 | 14.8 | 148 | 19.9 | 802 | 13.7 | 775 | 13.7 | 27 | 12.3 | ||

| 200 %—2 9 9 % | 1581 | 22.0 | 1422 | 22.0 | 159 | 22.3 | 1299 | 21.0 | 1250 | 21.1 | 49 | 18.1 | ||

| 300%—399% | 903 | 12.3 | 824 | 12.5 | 79 | 19.0 | 858 | 13.5 | 809 | 13.4 | 49 | 15.4 | ||

| ≥400% | 2656 | 37.3 | 2432 | 37.9 | 224 | 32.8 | 2699 | 43.4 | 2576 | 43.4 | 123 | 43.5 | ||

| Received public assistance since last interview | 2071 | 29.0 | 1799 | 28.0 | 272 | 37.2 | <0.001 | 1093 | 18.7 | 1042 | 18.7 | 51 | 19.9 | 0.53 |

| Any economic hardship, past 12 months | 1988 | 27.2 | 1707 | 26.0 | 291 | 37.2 | <0.001 | 1389 | 22.4 | 1312 | 22.1 | 77 | 27.5 | 0.11 |

| Home ownership | 3172 | 44.8 | 2949 | 46.2 | 224 | 32.2 | <0.001 | 2625 | 40.0 | 2554 | 40.7 | 71 | 23.7 | <0.001 |

| Subjective social status (mean)¶ | 4.97 | 5.02 | 4.59 | <0.001 | 5.01 | 5.02 | 4.95 | 0.66 | ||||||

All n are unweighted counts. Percentages are weighted and reflect column percentages within sex and sexual orientation groups and may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Design-based F-statistic of association between sexual orientation and covariate within each sex group unless otherwise noted.

Other, non-Hispanic includes Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian and self-reported ‘other’ race.

Urbanicitiy was defined using the population density of respondent’s Census tract: rural defined as fewer than 1000 people/square mile; urban defined as 1000 people or more/square mile.

′Other employment′ includes on disability, temporary parental leave, active military and incarcerated respondents.

Subjective social status on scale from 1 to 10, indicating where the respondent believed they fell relative to other people in the USA, with 1 being ‘the people who have the least money and education and the least respected jobs or no job’.

Cell size too small to report (eg, n≤3), per Add Health reporting requirements.

GED, graduate equivalence degree; HS, high school.

Table 2.

Sex-stratified regression analyses of associations between sexual orientation and socioeconomic status among wave IV National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Young Adult Health participants (n=14 051)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point estimate | 95% CI | Point estimate | 95% CI | Point estimate | 95% CI | Point estimate | 95% CI | |

| Females (n=7518) | ||||||||

| Respondent educational attainment, RRR (n=7518) | ||||||||

| <HS diploma or GED | 3.20*** | (2.23 to 4.58) | 3.50*** | (2.27 to 5.38) | ||||

| HS diploma or GED | 1.82** | (1.23 to 2.68) | 2.12*** | (1.40 to 3.20) | ||||

| Some college | 1.95*** | (1.48 to 2.56) | 2.14*** | (1.60 to 2.86) | ||||

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | Referent | Referent | ||||||

| Employment status, RRR (n=7518) | ||||||||

| Employed | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||||

| Unemployed | 2.05*** | (1.38 to 3.04) | 2.22*** | (1.51 to 3.26) | 1.92** | (1.29 to 2.85) | ||

| Homemaker | 1.27 | (0.90 to 1.80) | 1.19 | (0.85 to 1.67) | 1.04 | (0.74 to 1.46) | ||

| Student | 1.06 | (0.62 to 1.79) | 0.98 | (0.57 to 1.67) | 0.94 | (0.55 to 1.60) | ||

| Other | 1.52 | (0.95 to 2.41) | 1.50 | (0.93 to 2.42) | 1.32 | (0.82 to 2.13) | ||

| Personal income, RRR (n=7367) | ||||||||

| <US$10000 | 1.31 | (0.93 to 1.83) | 1.28 | (0.90 to 1.81) | 0.86 | (0.57 to 1.29) | 0.78 | (0.49 to 1.25) |

| US$10000–US$24999 | 1.62** | (1.16 to 2.26) | 1.51* | (1.09 to 2.11) | 1.08 | (0.74 to 1.57) | 1.06 | (0.74 to 1.52) |

| US$25000–$49999 | 0.93 | (0.66 to 1.32) | 0.91 | (0.64 to 1.29) | 0.75 | (0.52 to 1.10) | 0.76 | (0.53 to 1.11) |

| ≥ US$50 000 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Poverty-to-income needs ratio, RRR (n=7071) | ||||||||

| <100% | 1.27 | (0.96 to 1.66) | 1.32 | (0.96 to 1.83) | 0.89 | (0.63 to 1.27) | 0.83 | (0.57 to 1.21) |

| 100%−199% | 1.55* | (1.09 to 2.19) | 1.55* | (1.07 to 2.23) | 1.17 | (0.81 to 1.68) | 1.15 | (0.79 to 1.68) |

| 200%–299% | 1.17 | (0.89 to 1.53) | 1.18 | (0.89 to 1.57) | 0.95 | (0.72 to 1.25) | 0.95 | (0.71 to 1.25) |

| 300%–399% | 1.00 | (0.70 to 1.44) | 0.99 | (0.69 to 1.43) | 0.88 | (0.61 to 1.27) | 0.89 | (0.62 to 1.28) |

| ≥400% | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Received public assistance since last interview, OR (n=7511) | 1.52*** | (1.23 to 1.88) | 1.47*** | (1.18 to 1.84) | 1.22 | (0.98 to 1.52) | 1.18 | (0.93 to 1.49) |

| Any economic hardship past 12 months, OR (n=7513) | 1.69*** | (1.35 to 2.10) | 1.70*** | (1.36 to 2.14) | 1.46** | (1.15 to 1.85) | 1.42** | (1.11 to 1.81) |

| Homeowner, OR (n=7510) | 0.55*** | (0.43 to 0.71) | 0.56*** | (0.44 to 0.72) | 0.61*** | (0.48 to 0.79) | 0.62*** | (0.48 to 0.81) |

| Subjective social status, 3 (n=7503) | −0.43*** | (−0.61 to −0.26) | −0.36*** | (−0.53 to −0.20) | −0.20* | (−0.35 to −0.04) | −0.16* | (−0.31 to −0.01) |

| Males (N=6533) | ||||||||

| Respondent educational attainment, RRR (n=6533) | ||||||||

| <HS diploma or GED | 0.56 | (0.29 to 1.06) | 0.51 | (0.24 to 1.07) | ||||

| HS diploma or GED | 0.35** | (0.20 to 0.63) | 0.35** | (0.19 to 0.63) | ||||

| Some college | 0.78 | (0.50 to 1.20) | 0.82 | (0.53 to 1.26) | ||||

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | Referent | Referent | ||||||

| Employment status, RRR (n=6533) | ||||||||

| Employed | Referent | Referent | Referent | |||||

| Unemployed | 0.79 | (0.39 to 1.59) | 0.82 | (0.40 to 1.68) | 0.91 | (0.44 to 1.87) | ||

| Homemaker | † | † | † | † | † | † | ||

| Student | 1.89 | (0.81 to 4.37) | 1.81 | (0.74 to 4.45) | 1.62 | (0.68 to 3.85) | ||

| Other | 0.81 | (0.39 to 1.68) | 0.83 | (0.40 to 1.72) | 0.90 | (0.43 to 1.87) | ||

| Personal income, RRR (n=6401) | ||||||||

| <US$10 000 | 2.00* | (1.10 to 3.66) | 2.22* | (1.18 to 4.20) | 2.79** | (1.44 to 5.37) | 2.87** | (1.40 to 5.87) |

| US$10000-US$24999 | 1.81* | (1.07 to 3.07) | 2.10* | (1.18 to 3.74) | 2.60** | (1.42 to 4.74) | 2.48** | (1.29 to 4.75) |

| US$25000-US$49999 | 1.32 | (0.81 to 2.13) | 1.41 | (0.86 to 2.33) | 1.55 | (0.93 to 2.61) | 1.55 | (0.92 to 2.62) |

| ≥US$50000 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Poverty-to-income needs ratio, RRR (n=6115) | ||||||||

| <100% | 1.28 | (0.75 to 2.18) | 1.39 | (0.74 to 2.61) | 1.81 | (0.93 to 3.52) | 1.82 | (0.91 to 3.62) |

| 100%−199% | 0.89 | (0.43 to 1.83) | 0.95 | (0.43 to 2.09) | 1.13 | (0.48 to 2.63) | 1.11 | (0.46 to 2.66) |

| 200%—299% | 0.86 | (0.53 to 1.40) | 0.92 | (0.56 to 1.54) | 1.05 | (0.59 to 1.87) | 1.04 | (0.58 to 1.87) |

| 300%—399% | 1.14 | (0.69 to 1.88) | 1.22 | (0.74 to 2.01) | 1.33 | (0.79 to 2.22) | 1.31 | (0.78 to 2.21) |

| ≥400% | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Received public assistance since last interview, OR (n=6524) | 1.08 | (0.70 to 1.66) | 1.14 | (0.72 to 1.81) | 1.30 | (0.81 to 2.07) | 1.28 | (0.81 to 2.03) |

| Any economic hardship past 12 months, OR (n=6523) | 1.33 | (0.94 to 1.91) | 1.39+ | (0.97 to 2.00) | 1.56* | (1.08 to 2.27) | 1.56* | (1.07 to 2.28) |

| Homeowner, OR (n=6524) | 0.45*** | (0.32 to 0.63) | 0.45*** | (0.32 to 0.63) | 0.41*** | (0.29 to 0.58) | 0.42*** | (0.30 to 0.60) |

| Subjective social status, 3 (n=6519) | −0.06 | (−0.34 to 0.22) | −0.13 | (−0.42 to 0.16) | −0.24 | (−0.52 to 0.05) | −0.24+ | (−0.52 to 0.04) |

Model 1: crude/bivariate association between sexual orientation (sexual minority relative to sexual majority (referent)) and socioeconomic outcome variable in column 1.

Model 2: adjusted for age, race-ethnicity, parental educational attainment at wave I, receipt of public assistance prior to age 18 years, wave IV urbanicity; wave IV Census region.

Model 3: adjusted for all model 2 covariates and respondent educational attainment.

Model 4: adjusted for all model 3 covariates and wave IV employment status.

P<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Results not reported due to small cell size/instability of estimates.

GED, graduate equivalence degree; HS, high school; RRR, relative risk ratio.

Table 3.

Sex-stratified fitted*probabilities of socioeconomic outcomes by sexual orientation among wave IV National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Young Adult Health participants (n=14 051)

| Females (n=7518) | Males (n=6533) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterosexual (n=6757) | Sexual minority (n=761) | Heterosexual (n=6238) | Sexual minority (n=295) | |||||

| Point estimate | 95% CI | Point estimate | 95% CI | Point estimate | 95% CI | Point estimate | 95% CI | |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| <HS diploma or GED | 6.5% | (5.5 to 7.4) | 11.1% | (8.1 to 14.0) | 10.1% | (8.9 to 11.3) | 8.0% | (3.5 to 12.4) |

| HS diploma or GED | 13.5% | (12.0 to 14.9) | 14.9% | (11.3 to 18.5) | 21.9% | (19.9 to 23.9) | 11.2% | (6.4 to 16.1) |

| Some college | 43.6% | (41.7 to 45.6) | 51.1% | (46.2 to 56.0) | 41.1% | (38.9 to 43.2) | 46.6% | (38.4 to 54.8) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 36.4% | (34.1 to 38.8) | 22.9% | (18.4 to 27.5) | 26.9% | (24.7 to 29.2) | 34.2% | (26.6 to 41.8) |

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Employed | 77.5% | (76.1 to 78.9) | 70.6% | (66.3 to 75.0) | 84.7% | (83.1 to 86.3) | 84.0% | (78.5 to 89.5) |

| Unemployed | 5.0% | (4.3 to 5.8) | 10.0% | (7.0 to 13.0) | 7.2% | (6.0 to 8.4) | 5.9% | (2.0 to 9.7) |

| Homemaker | 9.8% | (8.7 to 10.8) | 10.5% | (7.7 to 13.3) | Not reported due to small cell size | |||

| Student | 3.5% | (2.9 to 4.2) | 3.2% | (1.5 to 4.8) | 2.1% | (1.6 to 2.5) | 3.7% | (0.7 to 6.7) |

| Other | 4.2% | (3.5 to 4.8) | 5.7% | (3.4 to 8.0) | 5.9% | (4.8 to 7.0) | 4.9% | (1.7 to 8.1) |

| Personal income | ||||||||

| <US$10 000 | 23.7% | (22.2 to 25.3) | 26.0% | (21.9 to 30.0) | 11.5% | (10.0 to 13.1) | 16.3% | (10.4 to 22.3) |

| US$10000–US$24999 | 24.0% | (22.6 to 25.3) | 31.1% | (26.5 to 35.7) | 18.8% | (17.2 to 20.4) | 25.5% | (18.4 to 32.7) |

| US$25000-US$49999 | 38.4% | (36.7 to 40.1) | 30.5% | (25.7 to 35.3) | 41.3% | (39.3 to 43.2) | 38.8% | (31.4 to 46.1) |

| ≥US$50 000 | 13.9% | (12.5 to 15.2) | 12.4% | (9.2 to 15.7) | 28.4% | (26.5 to 30.4) | 19.4% | (12.5 to 26.3) |

| Poverty-to-income needs ratio | ||||||||

| <100% | 12.6% | (11.4 to 13.9) | 13.9% | (10.8 to 16.9) | 8.7% | (7.5 to 9.9) | 11.5% | (6.6 to 16.4) |

| 100%–199% | 14.8% | (13.6 to 16.0) | 19.4% | (15.4 to 23.5) | 14.1% | (12.6 to 15.5) | 12.7% | (5.6 to 19.9) |

| 200%–299% | 22.1% | (20.7 to 23.5) | 22.4% | (18.5 to 26.2) | 21.1% | (19.5 to 22.6) | 18.8% | (12.6 to 25.0) |

| 300 %–3 99 % | 12.5% | (11.3 to 13.7) | 10.8% | (8.0 to 13.6) | 13.2% | (12.0 to 14.4) | 15.5% | (9.3 to 21.8) |

| ≥400% | 38.0% | (35.7 to 40.2) | 33.5% | (28.8 to 38.3) | 42.9% | (40.5 to 45.3) | 41.5% | (32.6 to 50.4) |

| Received public assistance since last interview | 27.8% | (25.8 to 29.8) | 34.9% | (30.3 to 39.5) | 19.0% | (17.2 to 20.8) | 20.9% | (14.4 to 27.5) |

| Any economic hardship past 12 months | 25.9% | (24.0 to 27.7) | 36.3% | (32.1 to 40.5) | 22.4% | (20.9 to 23.9) | 28.4% | (21.5 to 35.3) |

| Homeowner | 46.4% | (44.7 to 48.1) | 33.9% | (29.1 to 38.7) | 40.3% | (38.3 to 42.2) | 24.2% | (18.4 to 30.0) |

| Subjective social status (mean) | 5.02 | (4.95 to 5.10) | 4.66 | (4.49 to 4.83) | 5.00 | (4.93 to 5.08) | 4.88 | (4.60 to 5.15) |

A djusted for age, race-ethnicity, parental educational attainment at wave I, receipt of public assistance prior to age 18 years, wave IV urbanicity; wave IV Census region.

GED, graduate equivalence degree; HS, high school.

In order to explore potential effect modification by racial minority status (operationalised as black or Latino) versus the dominant group (white, non-Hispanic), SM by racial minority interaction terms were added to model 2 regressions. Because the ‘other’ racial-ethnic group was small and heterogeneous in terms of racial-ethnic identity, SES and group histories of racism, it was excluded from these analyses. The presence of a statistically significant interaction term at an alpha of 0.10 was used to determine the presence of possible effect modification (see online supplementary table A). Predicted probabilities were computed separately by sex, sexual orientation and racial minority/majority status and graphed for SES indicators where the association between sexual orientation and SES appeared to vary across racial minority/majority status. All analyses were conducted in STATA V.14,50 incorporating Add Health sampling weights and adjusting for the complex sampling design.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the analytic sample are presented in table 1. Most (92.7% weighted) of the respondents aged 24–34 years were heterosexual; however, 7.3% of respondents were categorised as SM because they reported bisexual, mostly homosexual or 100% homosexual identities or reported one or more lifetime same-sex sexual partners (if mostly heterosexual). A higher proportion of females (10.5%, n=761) were classified as SM than males (4.2%, n=295).

Females

Among females, SM were over-represented among those who did not complete an HS or GED and were under-represented among those who completed ≥bachelor’s degree compared with heterosexual females (table 1). Most females, across sexual orientation groups, were employed; however, SM females were somewhat under-represented among the employed and over-represented among the unemployed. SM females were slightly over-represented in the group reporting <US$25 000 in personal annual income, as well as in the near poor (100%–199% FPL) and highest (≥400% FPL) economic status groups. SM females were also more likely to report receipt of public assistance since the last interview, as well as economic hardship in the prior year, compared with heterosexual peers. They were also less likely to be homeowners and reported lower mean subjective social status scores.

After adjusting for covariates, the risk of completing ≤bachelor’s degree was significantly higher for SM females relative to heterosexual peers (table 2, model 2). In fact, the risk of not completing HS was three and a half times greater (relative risk ratio (RRR), 3.5, 95% CI 2.3 to 5.4), and the risk of completing a HS/GED or some college was twice as great (RRR 2.1, 95% CI 1.4 to 3.2; RRR 2.1, 95% CI 1.6 to 2.9, respectively). SM females were also more likely to be unemployed (RRR 2.2, 95% CI 1.5 to 3.3), to earn US$10 000–US$25 000 vs ≥US$50 000 in the prior year (RRR 1.5, 95% 1.1 to 2.1), and to be near poor (100%–199% FPL; RRR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.2) versus at ≥400% FPL. The odds of reporting public assistance since the last interview (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.8) and any economic hardship in the prior year (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.4 to 2.1) were elevated, while the odds of homeownership (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4 to 0.7) were reduced among minority versus heterosexual females. Subjective social status scores were an average of 0.4 points (95% CI −0.5 to −0.2) lower among SM females. Adjusting for respondent education (model 3) attenuated employment, receipt of public assistance and income-based indicators of SES; however, unemployment, homeownership, economic hardship and subjective social status remained statistically significantly different between SM and heterosexual females. Further adjustment for employment status (model 4) did not alter the pattern of results.

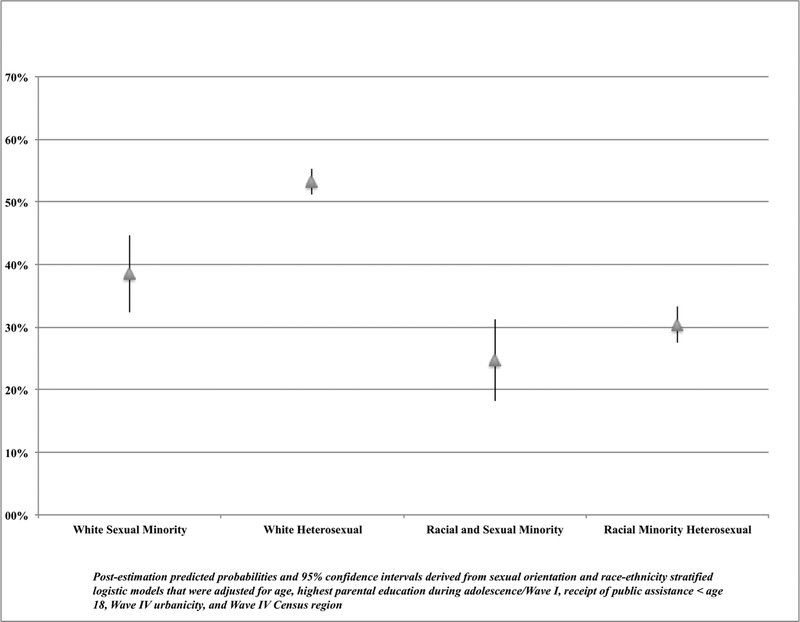

Among females, the association between sexual orientation and SES varied across racial minority versus majority groups for homeownership (F=3.80, df(1, 128), p=0.053) (figure 1). Differences in rates of homeownership by sexual orientation appeared larger among whites (38.5% SM vs 53.2% heterosexual) than among racial minorities (24.7% SM vs 30.4% heterosexual). Notably, rates of homeownership were lower among racial minorities and were the lowest among racial minority SM females.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of homeownership by sexual orientation and race-ethnicity among females in the wave IV National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Young Adult Health sample (n=6989).

Males

A larger proportion of SM males completed ≥bachelor’s degree compared with heterosexual males (table 1). The vast majority of males (approximately 85%) were employed across sexual orientation groups. SM males were over-represented at lower levels of personal income, but did not statistically significantly differ on the household-size adjusted poverty-to-income needs ratio. SM males were less likely to be homeowners than their heterosexual peers.

After adjusting for covariates (table 2, model 2), the risk of having an HS/GED compared with ≥bachelor’s degree was significantly lower (RRR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2 to 0.6) for SM males than heterosexual males. SM males were also more likely to earn <US$10 000 (RRR 2.2, 95% CI 1.2 to 4.2) and US$10 000–US$25 000 (RRR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.7) vs ≥US$50 000 in the prior year than heterosexual males. The odds of homeownership (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.6) were considerably lower among SM males. Adjusting for respondent education (model 3) magnified these inequities, indicating that, given high levels of education, SM males, on average, have fewer economic resources than expected and are at increased risk of economic hardship (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.3.) Adjustment for employment status (model 4) did not alter the pattern of results.

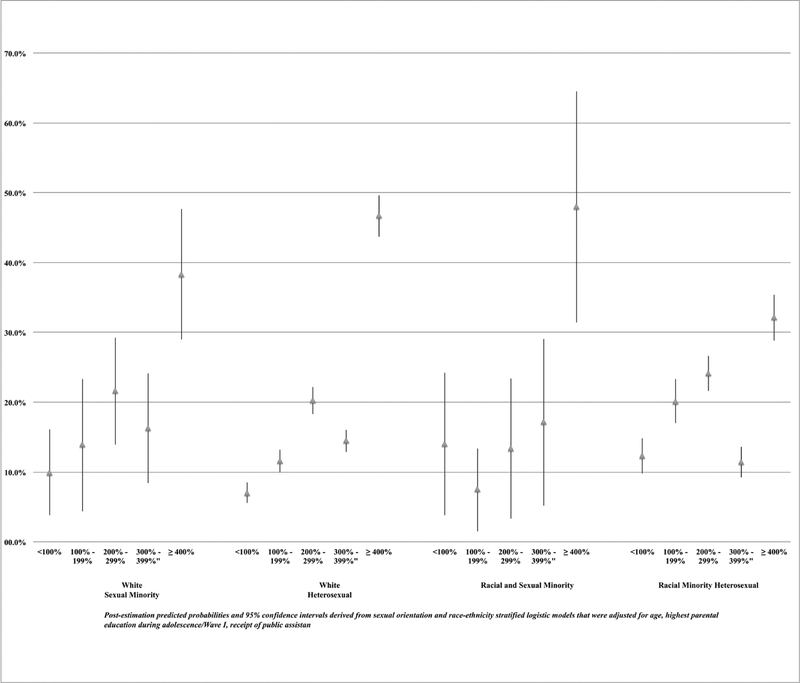

Among males, the association between sexual orientation and SES varied across racial minority versus majority groups for employment status (F=132.84, df(4, 128), p<0.001) and household poverty (F=2.43, df(4, 128), p=0.0514) (figure 2). Since most males, across sexual orientation and racial minority/majority groups, were employed (81.3%–85.0%), the other employment status categories included relatively few respondents and thus CIs around these estimates were quite wide. For instance, the predicted probability of unemployment was 4.0% (95% CI 0.5 to 7.5) for SM white males, 5.9% (95% CI 4.6 to 7.3) for heterosexual white males, 7.5% (95% CI −0.8 to 15.7) for racial minority SM males and 9.6% (95% CI 7.3 to 11.9) for racial minority heterosexual males. Given the instability of these estimates, and the lack of a clear pattern to report, no figure is included for employment. In contrast, the pattern observed for household poverty was clearer. The association between sexual orientation and household poverty was reversed across race, such that SM racial minority men were more likely to be living at ≥400% FPL than racial minority heterosexual men (48.0% vs 32.1%, respectively), whereas SM white men were less likely to be in the highest economic status group than their heterosexual white male counterparts (38.3% vs 46.7%, respectively).

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of poverty-to-income needs ratio by sexual orientation and race-ethnicity among males in the wave IV National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Young Adult Health sample (n=5896).

DISCUSSION

Socioeconomic inequities were observed among SM, particularly females, in the population-based Add Health sample. SM females were less likely to complete ≥bachelor’s degree, were more likely to be unemployed, to be near poor, to receive public assistance and to report economic hardship. They also reported lower subjective social status, which is unsurprising given that their objective SES was lower than that of heterosexual women and of SM men in this study.

Many of the observed economic inequities among women appeared to be related to differences in educational attainment. Economic inequities were attenuated after adjusting for education—suggesting that promoting the achievement of SM girls and young women may serve to reduce economic inequalities—regardless of the temporal ordering between educational completion and the expression of SM status. Proximal or ‘midstream’ factors that may underlie this gap include sexual victimisation,6 unplanned pregnancy51,52 and differential discipline in secondary schools,53 all of which are more common among SM women, and all of which are inversely associated with education.

Fewer significant sexual orientation differences in economic status emerged among males, which may be due to higher levels of education among minority males. In contrast to the pattern observed among females, SM males were more likely to complete college. This was an unexpected finding given that SM men report higher rates of school harassment than their heterosexual peers.54,55 One potential explanation for this pattern may include an investment in academic achievement among SM males as a way to garner positive attention.56 However, SM males were more likely to report lower personal incomes, and, after accounting for higher levels of education, were more likely to report economic hardship in the previous year, than their heterosexual counterparts. This pattern, observed previously in Add Health,57 and as reported in a recent meta-analysis,58 suggests that SM males experience wage discrimination.

Given the relationship between household composition and size-adjusted household economic status, post hoc descriptive analyses of household composition were conducted. SM females were more likely to live with a same-sex romantic partner (9% vs 0%) or with others (eg, relatives, roommates) (33.0% vs 27.1%) than with a different-sex partner (49.3% vs 63.8%) and were as likely to live alone (8.7% and 9.2%, respectively) as heterosexual women. A large, but somewhat smaller (55.9% vs 62.6%) proportion of SM females were living with a son/daughter under the age of 18 as compared with heterosexual women. These data suggest that lower personal incomes among SM women are the likely driver of their over-representation among the near-poor rather than differences in household composition.

Among men, SM men were more likely to live with a same-sex partner (15.4% vs 0%) or to live alone (22.6% vs 12.6%) or with others (42.5% vs 30.0%) versus with a different-sex partner (19.5% vs 57.4%) than heterosexual peers. SM males were also far less likely to report living with a minor son/daughter (11.1% vs 41.1%) than their heterosexual counterparts. These data suggest that a lower likelihood of a (lower59) female wage earner and a child in the household, as reflected in smaller average household size, among SM males may help to explain why personal income inequities were not sustained across household economic status.

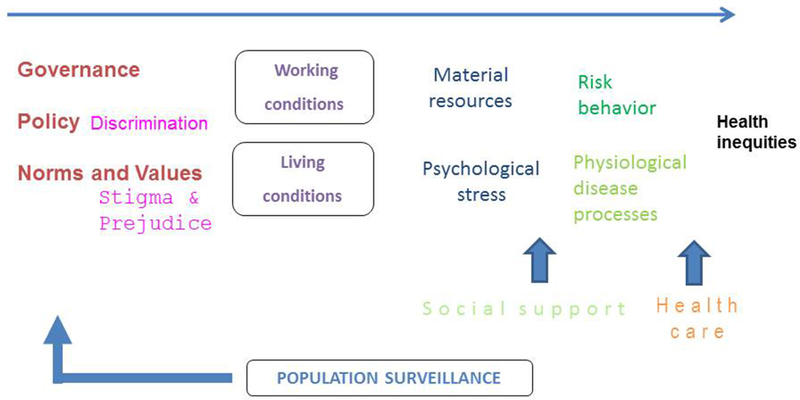

Although examining determinants of SES was beyond the scope of the present study, a social determinant of health framework, based on the Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health60 (figure 3), was used to guide our reflections about putative causes of observed SES patterns and their impact on health. Importantly, in this framework, norms and values that privilege the dominant group (heterosexuals) and stigmatise others (sexual minorities) shape living and working conditions, including risk of sexual assault, access to health services and the presence of children in the household. Daily conditions are themselves influenced by governmental and institutional (eg, school discipline) policy.

Figure 3.

Social determinants of population health.

Working through potential contributors to lower rates of home-ownership among SM, as an illustrative example, we consider upstream determinants of material resources (both savings and income) and access to loans. Employment discrimination by sexual orientation is prohibited in only 22 states,61 is more commonly experienced by SM62 and may contribute directly to economic status through earnings (joblessness, underemployment), as well as, indirectly, by limiting access to employer-provided health insurance.63 Same-sex couples were not granted the right to marry across the USA until 26 June 201564; marriage facilitates access to mortgage loans,65 as well as health insurance coverage.66 Medical expenses related to lack of insurance or poor coverage impact savings and are significant contributors to bankruptcy.67 Strained parental relationships7,68,69 may further reduce access to material support (eg, housing,70 college tuition support, health insurance coverage, loans and gifts, loan cosignature) for SM. Intergenerational transfers are estimated to account for approximately 20% of personal wealth.71 Lastly, a preference or need to live in more tolerant (eg, those with local non-discrimination protections), but expensive urban areas72,73 may also impact economic resources and rates of homeownership.

Although an intersectional analysis that considers racial inequality as an important determinant of population patterns of SES was beyond the scope of the current paper, we did explore whether observed sexual orientation and SES patterns differed between racial minorities (black and Latino/as) and the majority (whites) separately for females and males. Patterns differed for 3 out of 16 SES indicators. Among women, sexual orientation inequities in homeownership were more pronounced for whites than racial minorities. Rates of homeownership were the lowest for SM racial minority women and highest for heterosexual white women. Among men, racial minority men were more likely to be in the highest household economic status group than were racial minority heterosexual men, whereas white SM men were less likely to be in the highest household economic status group compared with white heterosexual men. These patterns should be further explored in large population-based datasets, such as those collected by the US Census Bureau, that would also allow for more nuanced comparisons by race-ethnicity.

This study is among the first to explore sex and sexual orientation difference in SES in a nationally representative sample. By using multiple indicators of SES collected by Add Health, our study offers a more comprehensive exploration of SES than has been previously explored in the peer-reviewed literature. Our sexual orientation measure builds on studies that relied on US Census surveys which identified SM on the basis of household composition and focused on same-sex versus different-sex married or cohabitating couples74,75—missing respondents who are single, may not be living with a partner and bisexuals in different-sex relationships. However, as reported above, only 9% and 15.4% of SM women and men, respectively, were living with same-gender partners, suggesting that the SM group identified through a measure that includes a broader array of sexuality options (ie, mostly homosexual, bisexual, mostly heterosexual) identifies a broader group of SM than would be identified through a measure that includes a handful of identity-based options (eg, heterosexual, lesbian or gay, bisexual). These differences in the composition of this SM sample should be considered by readers when comparing findings with studies that used different sexual orientation measures.

Limitations of our study include a reliance on self-report measures; however, we have no reason to suspect systematic reporting bias by sexual orientation. We do not have data on when a SM identity was developed relative to our outcomes and, thus, issues of temporality may impact our results. For instance, models that include respondent education adjust for earlier life differences in SES across groups, which are appropriate if education concluded prior to the development of an SM identity, but may underestimate the effect of SM status on economic status when education was influenced by an individual’s sexual identity. Findings may mask variability in the relationship between sexual orientation and SES across urbanicity and region76; however, exploring these potential differences was beyond the scope of the present study. Findings may also mask variability across gender identity or transgender versus non-transgender (cisgender) status77; however, current gender identity and assigned sex at birth were not collected in Add Health until wave 5 and these new data are not yet available. Lastly, the age of the Add Health cohort (36–44 years) may limit generalisability to other cohorts.

SES is a fundamental contributor to health across the life course26,27 and varies by sexual orientation. Frameworks to analyse sexual orientation inequities in health should consider stigma78,79 and both material and psychosocial pathways to health.33,80 Discrimination, rejection and harassment arise as a consequence of stigma and give rise to what has been termed ‘minority stress’17; however, an over-reliance on Minority Stress theory,1 or on psychosocial theories81 more broadly, to understand population patterns of health will overlook upstream drivers of these conditions. Data gaps should be addressed, specifically, sexual orientation (and gender identity) measures should be added to the Survey of Income and Program Participation, and to administrative systems that track usage of poverty reduction programmes, in order to evaluate the impact of public safety net programmes on the economic status of the population. Future studies should explore the impact of public policies such as marriage, non-discrimination protections and universal health insurance, on earnings and economic status across place and over time, in order to better elucidate the ways in which policies impact SES across sexual orientation groups. Finally, future research should focus on understanding how gender, racial and SM inequality manifests in population patterns of SES at various points in the life course to shed light how and when to intervene to reduce SES inequities and/or to improve the SES of specific population subgroups (eg, SM racial minority women).

Supplementary Material

What is already known on this subject.

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a fundamental contributor to health; however, limited research has examined sexual orientation differences in SES.

Efforts have been hindered by lack of inclusion of sexual orientation identity measures in the nation’s primary sources of economic information about the American public (ie, American Community Survey, Current Population Survey and the Survey of Income and Program Participation), as well as by the limited number of indicators of economic status that are included in population-based health surveys that are beginning to assess sexual orientation.

What this study adds.

This study contributes new information about SES by sexual orientation and sex in the nationally representative Add Health sample and provides an agenda for future research on social determinants of observed SES inequities.

Findings indicate that poverty, with accompanying economic strain, is an unappreciated ‘sexual minority’ issue for women.

Among men, lower personal incomes and rates of homeownership, despite higher educational attainment, were observed for sexual minorities.

SES should be considered an important pathway through which sexual orientation health inequities are generated.

Modification analyses suggest that sexual orientation and SES patterns vary between racial minorities (defined as black or Latino) and whites and are different for women and men.

These findings should be replicated in large datasets that allow for more nuanced comparisons across racial-ethnic groups and unpacked.

Future research is needed on upstream SES determinants (eg, marriage, non-discrimination protections, universal healthcare, minimum wage rates, poverty reduction programmes, educational and housing polices) to inform strategies to reduce observed SES inequities along multiple axes of inequality and to improve population health.

cknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ronald R Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design.

Funding This study was funded by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (10.13039/100009633) and grant number: 3P01HD031921-18S1, 5 R24HD050924, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations.

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.IOM (Institute of Medicine). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Physical health complaints among lesbians, gay men, and bisexual and homosexually experienced heterosexual individuals: results from the California Quality of Life Survey. Am J Public Health 2007;97:2048–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, et al. Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9–12--youth risk behavior surveillance, selected sites, United States, 2001–2009. MMWR Surveill Summ 2011;60:1–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walters ML, Chen J, Breiding MJ. The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, et al. Elevated risk of posttraumatic stress in sexual minority youths: mediation by childhood abuse and gender nonconformity. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1587–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saewyc EM, Skay CL, Pettingell SL, et al. Hazards of stigma: the sexual and physical abuse of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents in the United States and Canada. Child Welfare 2006;85:195–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM. Reports of parental maltreatment during childhood in a United States population-based survey of homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual adults. Child Abuse Negl 2002;26:1165–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greytak EA, Kosciw JG, Diaz RM. Harsh realities: the experiences of transgender youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN: New York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lombardi EL, Wilchins RA, Priesing D, et al. Gender violence: transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. J Homosex 2001;42:89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blosnich J, Lee JG, Horn K. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tob Control 2013;22:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bye L California lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgender (LGBT) tobacco use survey-2004. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J Homosex 2011;58:10–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2007;37:527–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuttbrock L, Hwahng S, Bockting W, et al. Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the life course of male-to-female transgender persons. J Sex Res 2010;47:12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilman SE, Cochran SD, Mays VM, et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health 2001;91:933–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cochran SD, Mays VM, Sullivan JG. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71:53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cochran SD, Mays VM, Alegria M, et al. Mental health and substance use disorders among Latino and Asian American lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75:785–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makadon HJ. The Fenway guide to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. 2nd edn. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Sexual orientation and mortality among US men aged 17 to 59 years: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Am J Public Health 2011;101:1133–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One 2011;6:e17502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yancey AK, Cochran SD, Corliss HL, et al. Correlates of overweight and obesity among lesbian and bisexual women. Prev Med 2003;36:676–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Struble CB, Lindley LL, Montgomery K, et al. Overweight and obesity in lesbian and bisexual college women. J Am Coll Health 2010;59:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1953–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. U.S. disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health 2008;29:235–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch J, Kaplan G, Berkman L, et al. Socioeconomic position, in Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muntaner C, Eaton WW, Diala C, et al. Social class, assets, organizational control and the prevalence of common groups of psychiatric disorders. Soc Sci Med 1998;47:2043–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Zenk SN, et al. Psychosocial stress and social support as mediators of relationships between income, length of residence and depressive symptoms among African American women on Detroit’s eastside. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:510–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ, Whitfield K. Life-course financial strain and health in African-Americans. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:259–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dijkstra-Kersten SM, Biesheuvel-Leliefeld KE, van der Wouden JC, et al. Associations of financial strain and income with depressive and anxiety disorders. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health 2010;100(Suppl 1):S186–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynch JW, Smith GD, Kaplan GA, et al. Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ 2000;320:1200–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badgett MV, Durso LE, S A. New patterns of poverty in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community. CA: UCLA, Williams Institute, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dilley JA, Simmons KW, Boysun MJ, et al. Demonstrating the importance and feasibility of including sexual orientation in public health surveys: health disparities in the Pacific Northwest. Am J Public Health 2010;100:460–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Castro AB, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Examining alternative measures of social disadvantage among Asian Americans: the relevance of economic opportunity, subjective social status, and financial strain for health. J Immigr Minor Health 2010;12:659–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahn JR, Pearlin LI. Financial strain over the life course and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav 2006;47:17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tucker-Seeley RD, Harley AE, Stoddard AM, et al. Financial hardship and self-rated health among low-income housing residents. Health Educ Behav 2013;40:442–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gates GJ, Newport F. Newport, special report: 3.4% of U.S. Adults Identify as LGBT, in Gallup: Gallup.com, 2012.

- 40.Harris KM. The national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health: research design. 2009. http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- 41.Carolina Population Center. Add health. questions about data. 2018. http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/faqs/aboutdata/index.html#why-are-there-1 (cited 11May 2018).

- 42.Allison PD. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perlis TE, Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, et al. Audio-computerized self-interviewing versus face-to-face interviewing for research data collection at drug abuse treatment programs. Addiction 2004;99:885–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.US Census Bureau. Table F-1. Income Limits for Each Fifth and Top 5 Percent of Families (All Races): 1947 to 2014. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements. http://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-inequality.html (cited 11 Aug 2016).

- 45.US Census Bureau. Poverty thresholds. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html (cited 11 Aug 2016).

- 46.US Census Bureau. How the Census Bureau measures poverty. http://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty/guidance/poverty-measures.html (cited 11 Aug2016).

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National health and nutrition examination survey questionnaire 2005–2006 data documentation, codebook, and frequences food security (FSQ-D). 2005–2006. Hyattsville, MD: U.S: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adler NE, Stewart J. The Psychosocial Working Group. Chapter 14. the macarthur scale of subjective social status. In: Psychosocial Notebook. University of California, San Francisco: MacArthur Research Network on SES and Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.US Census Bureau. Census 2000 Urban and Rural Classification. (cited 7 Feb 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 50.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saewyc EM, Bearinger LH, Blum RW, et al. Sexual intercourse, abuse and pregnancy among adolescent women: does sexual orientation make a difference? Fam Plann Perspect 1999;31:127–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldberg SK, Reese BM, Halpern CT. Teen pregnancy among sexual minority women: results from the national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health. J Adolesc Health 2016;59:429–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Himmelstein KE, Brückner H. Criminal-justice and school sanctions against nonheterosexual youth: a national longitudinal study. Pediatrics 2011;127:49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berlan ED, Corliss HL, Field AE, et al. Sexual orientation and bullying among adolescents in the growing up today study. J Adolesc Health 2010;46:366–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedman MS, Koeske GF, Silvestre AJ, et al. The impact of gender-role nonconforming behavior, bullying, and social support on suicidality among gay male youth. J Adolesc Health 2006;38:621–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML. The social development of contingent self-worth in sexual minority young men: an empirical investigation of the “best little boy in the world” hypothesis. Basic Appl Soc Psych 2013;35:176–90. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sabia J Sexual orientation and earnings in young adult adulthood: New evidence from Add Health. ILL Review 2014;67:209–67. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klawitter M Meta-analysis of the effects of sexual orientation on earnings. Ind Relat 2015;54:4–32. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Joint Economic Committee UC Gender pay inequality. consequences for women, families and the economy. 2016. www.jec.senate.gov [Google Scholar]

- 60.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health: discussion paper for the commision on social determinants of health, department of equity, poverty and social determinants of health, evidence and information, editor. Geneva: WHO, Policy Cluster, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Movement Advancement Project. Nondiscrimination laws. Employment August 10 2017. (cited 14 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1869–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zuvekas SH, Taliaferro GS. Pathways to access: health insurance, the health care delivery system, and racial/ethnic disparities, 1996–1999. Health Aff 2003;22:139–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Supreme Court Reporter. Obergefell v. Hodges, in 576 U.S, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller JJ, Park KA. Same-sex marriage laws and demand for mortgage credit. Rev Econ Househ 2016;92. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gonzales G, Blewett LA. National and state-specific health insurance disparities for adults in same-sex relationships. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e95–e104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Himmelstein DU, Warren E, Thorne D, et al. Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy. Health Aff 2005;Suppl Web Exclusives:W5-63-W5-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, et al. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics 2009;123:346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, Beauchaine TP. Victimization over the life span: a comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73:477–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McLaughlin KA, Greif Green J, Gruber MJ, et al. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:1151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.William GG, Scholz JK. Intergenerational Transfers and the Accumulation of Wealth. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 1994;8:145–60. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gary J Same-sex couples and the gay, lesbian, bisexual population: new estimates from the American Community Survey: The Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation Law and Public Policy, UCLA School of Law, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jepsen LK, Jepsen CA. An empirical analysis of the matching patterns of same-sex and opposite-sex couples. Demography 2002;39:435–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gates GJ. Demographics of married and unmarried same-sex couples: analyses of the 2013 American Community Survey. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Black D, Gates G, Sanders S, et al. Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the United States: evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography 2000;37:139–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hasenbush A The LGBT divide: a data portrait of LGBT people in the midwestern, moutain & southern states 2014. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carpenter CS, Eppink ST, Gonzales G, et al. Transgender status, gender identity, and economic outcomes in the United States. in progress. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet 2006;367:528–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma: Research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol 2016;71:742–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Epidemiology Krieger N. and the web of causation: has anyone seen the spider? Soc Sci Med 1994;39:887–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Krieger N A glossary for social epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.