Abstract

Background:

Few studies have examined the complex relationship of migration stress and depression with sexual risk behaviors among migrants. The relationship between migration stress and sexual risk behaviors may be mediated by depression, and the mediation process may be modified by social capital. The study aims to investigate this moderated mediation among rural-to-urban migrants.

Methods:

Data were collected from rural-to-urban migrants in China. Migration stress, depression, and social capital were measured with validated scales and used as predictor, mediator and moderator, respectively, to predict the likelihood of having sex with risk partners. Mediation and moderated mediation models were used to analyze the data.

Results:

Depression significantly mediated the migration stress–sex with risk partner relationship for males (the effect [95%CI] = 0.36 [0.08, 0.66]); the mediation effect was not significant for females (0.31 [−0.82, 0.16]). Among males, social capital significantly moderated the depression-sex with risk partner relation with moderation effect −0.12 [−0.21, −0.04], −0.21 [−0.41, −0.01] and −0.17 [−0.30, −0.05] for total, bonding and bridging capital respectively.

Conclusion:

Social capital may weaken the association between migration stress and sexual risk behavior by buffering the depression-sexual risk behaviors association for males. Additional research is needed to examine this issue among females.

Keywords: Social capital, Depression, Risk behaviors, Moderated mediation, Migrants

Introduction

Migration and sexual risk behaviors

In pursuit of better quality of life, a great number of people leave their homes and migrate to new destinations (Chen, Yu, Zhou, et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2017). Worldwide, there are approximately 250 million people who migrate to other countries, and more than 750 million people who move domestically every year (World Bank, 2017). The process of migration is challenging. Numerous stressors are generated when migrants leave the familiar environment, culture and lifestyles in the place of origin, and settle down in a new environment, assimilate themselves into new neighborhood and culture, adapt to new lifestyles and work environments (Berry, 1997, 2006; Tomás-Sábado, Qureshi, Antonin, & Collazos, 2007; Yu, Chen, & Li, 2014). These stressors may put migrants at increased risk to engage in health risk behaviors, such as using alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs and taking part in sexual risk behaviors (Borges, Medina-Mora, Breslau, & Aguilar-Gaxiola, 2007; Fitzpatrick, Piko, Wright, & LaGory, 2005; Yu et al., 2017).

Among these health risk behaviors, engaging in sexual risk behaviors is of great significance because of numerous negative consequences (Boyer et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 1993). Sexual risk behaviors, such as having sex with sex workers, having sex without condom, and multiple sexual partners, are not safe. Engagement in any of these behaviors will directly put migrants at risk for HIV infection and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (Giannou et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2017). One study in Ethiopia reported that among migrant workers who had sexual intercourse in the past six months, 74% had sex with sex workers, 49% had unprotected sex, and 69% had multiple sexual partners (Tiruneh, Wasie, & Gonzalez, 2015). Thus, it will be of great significance to investigate factors and mechanisms related to sexual risk behaviors among migrant populations.

Rural-to-urban migrants in China

Along with the rapid economic growth since the 1980s, and more and more rural residents in China migrated to urban areas to seek better opportunities. There are approximately 280 million rural migrants in China (National Bureau of Statistics of the PRC, 2016). As being discussed in the previous section that migration is a challenging process. The challenging events may increase the likelihood for these migrants to engage in sexual risk behaviors. One study conducted among 5,996 rural migrants in Shanghai, China reported that 58% of them did not use condom when having sex, and 15% had sex with casual extramarital partners (Dai et al., 2015). The large number of rural migrants and the high rate of sexual risk behavior among them provide a window of opportunities to investigate the influential factors that are related to sexual risk behaviors and underlying behavioral mechanisms.

Effects of migration stress and depression on sexual risk behaviors

Stress is a general feeling of strain and pressure when individual’s internal capacity could not meet the demands of external environment (Lazarus, 2006). Migration stress is one type of stress that are directly related to the strain and pressure experienced by migrants during the process of migration (Chen, Yu, Gong, Zeng, & MacDonell, 2015). Migration stress is a significant threat to migrants’ health (Tomás-Sábado et al., 2007). Study findings indicate that experience of migration stress can increase the likelihood for migrants to engage in sexual risk behaviors (Yu et al., 2017). An immediate negative consequence from stress is reduction in mental health (Tennant, 2002). Studies have documented that poor mental health, including depression, can increase the risk for people to engage in sexual risk behaviors (Williams & Latkin, 2005; H. Yang et al., 2005). Engaging in sexual risk behaviors could be a strategy for migrants to cope with stress and depression (Amirkhanian et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2017).

Poor mental health mediates the migration stress and sexual risk behaviors relationship

The relationship between migration stress and poor mental health has been well established, migration stress is positively associated with multiple poor mental health symptoms, including depression, anxiety, somatization, hostility and obsessive-compulsive disorders (Hovey & Magaña, 2000; Sirin, Ryce, Gupta, & Rogers-Sirin, 2013; Yu et al., 2017). One of our previous studies observed a positive relationship between poor mental health and engagement in sexual intercourse with high risk partners, such as sex workers (Yu et al., 2017). We also found that poor mental health can mediate the association between migration stress and sexual risk behaviors among migrants (Yu et al., 2017). The relationship between migration stress and poor mental health, as well as the relationship between poor mental health and sexual risk behaviors form a mediation relationship, making it hard if not impossible to control sexual risk behaviors among migrant population. Therefore, identification of factors that can moderate this mediation process would be of great significance for devising evidence-based intervention for risk reduction.

Social capital and health

Social capital is defined based on a person’s network connections. Among a person’s network contacts, those who are trustworthy, reciprocal and resource-rich are the social capital possessed by the person (Chen, Stanton, Gong, Fang, & Li, 2009). Personal social capital acts as a function to integrate oneself with others from an inner circle stretching to the broad society. Social capital can facilitate access to informational, instrumental and emotional support from people in the society to improve quality of life (Requena, 2003; Rogers, Halstead, Gardner, & Carlson, 2011). In addition, social capital can strengthen social cohesion and trust in community by growing connections among community members (Smith & Kawachi, 2014). Adequate community social capital is required for collective efficacy–an informal social control of social undesirable behaviors, including sexual risk behaviors (Skrabski, Kopp, & Kawachi, 2004).

Social capital can be divided into bonding and bridging capital (Kawachi, Subramanian, & Kim, 2008; Putnam, 2000). Bonding capital refers to the social capital network contacts who share similar characters, interests and values. Bridging capital, on the other hand, refers to the social capital contacts who may not be similar but connected together through various social groups, organizations and institutions, such as church, sports team and professional associations (Chen et al., 2009; Kawachi et al., 2008). People accumulate bonding capital through free contact with others and accumulate bridging capital by participating in various groups/organizations (Chen, Wang, Wegner, et al., 2015).

The positive impact of social capital has long been reported, and high social capital promotes health protective behaviors, inhibit health risk behaviors, and enhance mental health and wellbeing (Almedom, 2005; Lundborg, 2005; Smith & Kawachi, 2014). People with higher social capital are less likely to suffer from mental health problems (Harpham, Grant, & Rodriguez, 2004). Social capital can also protect people from sexual risk behaviors. For example, studies reported negative associations between social capital and risky sex and positive associations between social capital and safer sex (Crosby, Holtgrave, DiClemente, Wingood, & Gayle, 2003).

Potential moderation effect of social capital

A previous study has demonstrated the effect of poor mental health in mediating the migration stress–sexual risk behavior relation (Yu et al., 2017). The characteristics of social capital suggest that social capital may act as a buffer attenuating the impact of migration stress on the likelihood to engage in risky sex by weakening the stress–depression relation. Despite the fact that the risk of depression is higher for individuals with greater migration stress (Liu et al., 2016); the risk might be lower for individuals with more social capital due to emotional, informational and social support (Kawachi et al., 2008; Whiteford, Cullen, & Baingana, 2005). However, no reported study has examined this moderation effect among any migrant populations.

Adequate social capital may also protect depressed migrants from engaging in sexual risk behaviors as a coping strategy. Different from stress that is volatile, depression usually lasts for days and weeks if not months. With adequate social capital, instead of seeking for sexual risk behaviors, a migrant can cope with depression by interacting with many of his/her trustworthy, resource-rich, and reciprocal friends either individually or through group activities (Chen et al., 2009). This protective effect can also reveal as a negative moderation effect. To our knowledge, no study in the literature has ever investigated the important role of social capital as a moderator on poor mental health and sexual risk behaviors.

Social capital among migrants

Social capital is particularly relevant for studying the risk of mental health and risk behaviors among migrants. Compared to non-migrants, migrants suffer from a big social capital loss when they leave the place origin; migrants have to reconstruct their social capital in the destination (Chen et al., 2011; Flynn, 2004; Tilly, 2007). When leaving the place of origin, migrants lost almost all the social capital they previously accumulated because migration physically break all the ties they have built with people, groups and organizations in the place of origin (Chen et al., 2011). When settling down in the destination, migrants may experience unprecedented difficulties to build social capital in the new environment with few network contacts (Chen et al., 2011, 2009; Ryan, Sales, Tilki, & Siara, 2008).

Another challenge for migrants to rebuild their social capital is that most migrants do not have a permanent residency in the destination; they have to move to find the best (Bhugra, 2004; Li et al., 2007). The relatively low social and economic status and the high mobility will prevent migrants from initiating, maintaining, and growing trustworthy and reciprocal relationships with resource-rich people in a new environment, reducing the opportunity for them to accumulate social capital (Chen et al., 2011). Therefore, migrants may experience a large reduction with a large variation in social capital. These characteristics are ideal for us to examine levels of social capital and its effects on mental health and risk behaviors among migrants while knowledge gained on social capital will provide data essential for prevention since social capital is a modifiable factor through intervention (Gong, Chen, & Li, 2015; Ottesen, Jeppesen, & Krustrup, 2010).

Purpose of this study

The purpose of this study is to investigate the potential moderation effect of social capital in attenuating the migration stress-depression and depression-risk sexual behavior relationships with data from a random sample of rural-to-urban migrants. The ultimate goal is to enhance our understanding of behavioral mechanisms underlying the complex relationships among migration stress, mental health and sexual risk behaviors, supporting more effective evidence-based prevention intervention programs targeting this population.

Materials and Methods

Participants and sampling

Data were derived from a project to investigate rural-to-urban migration and HIV risk behavior in China. The participants were rural-to-urban migrants with 18–45 years of age, possessing legal rural residence (Hukou), and have migrated to the current city for at least one month. These migrants were randomly selected in Wuhan, China. Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei Province, is locating in the central China with a total population of more than 10 million and per capita GDP of $17,000 in 2015 (Statistical Bureau of Wuhan, 2015).

Participants were sampled using a 4-stage GIS/GPS-assisted sampling methods (Chen et al., 2018). First, the geographic area was divided into 100*100-meter mutually exclusive geographic units (named as geounits) to form the primary sampling frame (PSF). Non-residential areas, including lakes, factories, streets, were excluded. Second, a total of 60 geounits were randomly selected from the PSF. Optimal design for cost-effective was used so that more geounits were allocated in the area with higher density of rural-to-urban migrants (Cochran, 1977; Grove, 2004; Spiegelman & Gray, 1991). From each geounit, 20 participants with one participant per gender per household were randomly sampled. If more than one participant was eligible in one selected household, one was selected using a random digit method. Written informed consents were collected from the participants.

Procedure of data collection

Data collection was completed during 2011–2013. Data were collected using the Migrant Health and Behavior Survey, delivered using an Audio Computer-Assisted Self Interviewing (ACASI) system. The survey was anonymous and confidential. Participants completed the survey in a private room. After completing the survey, participants were provided a $5 incentive.

Among the total 1,414 eligible participants, 121 (8.6%) refused to participate. At the end of the survey, participants were asked a final question of “How likely you have truly answered the questions” with answer options of “1=100% true, 2=80% true, 3=50% true, 4=20% true, and 5=not true at all”. Of the 1,293 who completed the survey, 158 (12.2%) were excluded because they reported that 50% or more of their answers were not reliable, yielding a final sample of 1,135 participants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Wayne State University, Wuhan Center for Disease Prevention and Control and University of Florida.

Measurements

Predictor variable X -- migration stress

Migration stress was measured using the 16-item Domestic Migration Stress Questionnaire (DMSQ) (Chen, Yu, Gong, et al., 2015). The DMSQ consists of 16 items and four subscales, including separation from the place of origin, lack of self-confidence, rejection in the destination, and maladaptation, with four items per subscale. Individual items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale varying from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The Cronbach’s alpha for DMSQ was 0.92 in this study. Mean score of the total DMSQ scale was computed such that higher scores indicating higher levels of migration stress.

Mediator variable M -- depression

Depression was measured using the five-item Depression Subscale in the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). Individual items were measured using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The reliability for the depression subscale was 0.87 in the study. Mean scores were computed such that higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms.

Moderator variable V -- social capital

Social capital was assessed using the Personal Social Capital Scale (PSCS) (Chen et al., 2009). PSCS is a theory-based instrument with adequate reliability and validity. The instrument has been verified by studies conducted in China and the United States (Archuleta & Miller, 2011; Chen et al., 2009; Chen, Wang, Wegner, et al., 2015; Wang, Chen, Gong, & Jacques-Tiura, 2013). This scale consists of 32 items with two subscales: Bonding Capital (24 items) and Bridging Capital (8 items).

The bonding capital was measured using four attributes: (1) personal network size measured as the perceived number of frequently connected persons (1=very few and 5=many), followed by three questions to assess among these connected persons, how many (1=very few and 5=almost everyone) are: (2) trustful, (3) reciprocal, and (4) resource rich. These four attributes are assessed among six subgroups of people: (1) family members, (2) relatives, (3) neighbors, (4) friends, (5) colleagues, and (6) old classmates to generate the total bounding social capital.

The bridging capital was assessed using four attributes, including (1) the perceived number of groups/organizations by which a person is often connected with (1=a few and 5=a lot), followed by three questions asking among the groups/organizations how many (1=a few and 5=almost all) (2) represent his/her rights and interests, (3) will provide help if needed, and (4) have a lot of resources. Likewise, these four attributes are assessed among two types of groups/organizations: (1) governmental, economic and social groups/organizations, and (2) cultural, recreation and leisure groups/organizations. The Cronbach alpha was 0.91 for the total PSCS, 0.88 for the Bonding Social Capital Subscale, and 0.93 for the Bridging Social Capital Subscale, respectively.

Social capital scale scores for individual participants were computed such that higher scores indicating higher level of social capital. First, mean scores were computed for the eight attributes (four for bonding social capital and four for bridging social capital) by averaging the item scores over the six network subgroups for bonding and the two groups/organizations for bridging. Bonding capital and bridging capital scores were thus calculated separately by summation of the four attribute mean scores, divided by four; and finally the total social capital scores as summation of the bonding and the bridging capital scores, divided by two.

Outcome variable Y - Having sex with risky partners

Having sex with risky partners was assessed based on participants’ response to the question, “Have you ever engaged in sexual intercourse with any of the following persons in the past year?” with a checklist of 6 options: (1) commercial sexual workers, (2) injection drug users, (3) commercial blood donors, (4) people living with HIV/AIDS, (5) people living with other sexually transmitted diseases, and (6) same gender partners. A participant was classified as having had sex with risky partners if he/she responded positively to any of these 6 types of risky partners. This binary variable (1=having sex with risk partners, 0=not having sex with risk partners) was used as outcome in the study.

Condom use behavior

Following the question regarding the sexual behaviors with risk partners, another question about condom use was asked as “When you have had sex with these risk partners, how often did you use condom?” with answer options ranging from “1=never” to “4=always”.

Demographic and migration experiences

Five demographic variables included in this study were age, gender, education, marital status, and income level. Eight variables describing migration experience were: number of cities ever migrated to, duration living at Wuhan, times of visiting hometown annually, if send money home, intention to move to another city, type of residential locations, if living in a rental house, and if living alone.

Statistical analysis

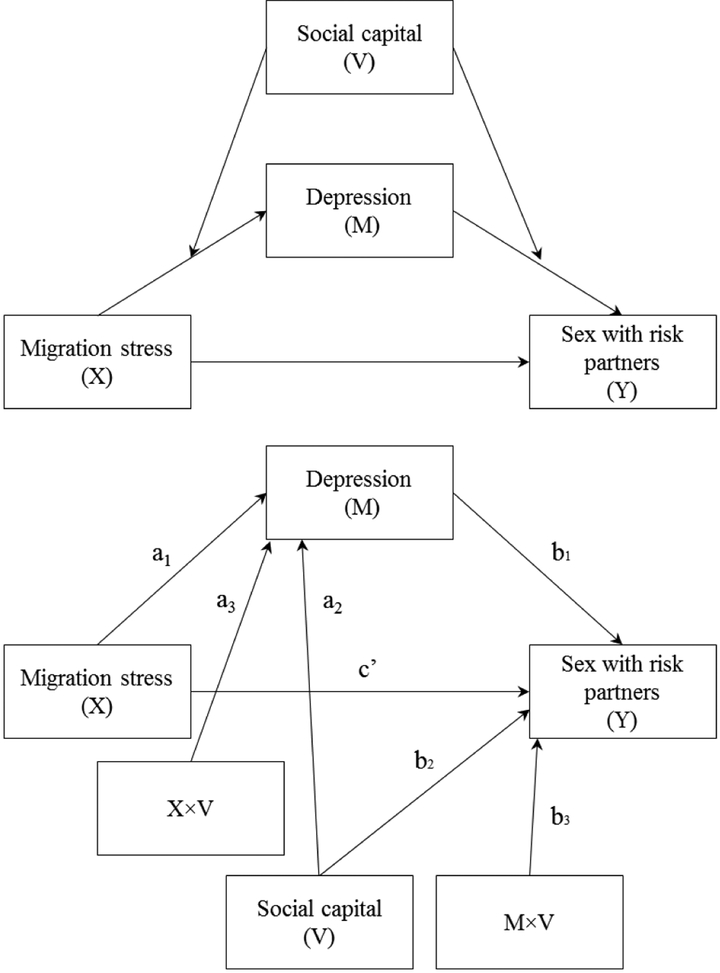

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample. Pearson correlation analysis was used to assess the relationship between social capital, migration stress, depression and having sex with risk partners. Mediation model was used to investigate the role of depression in mediating the relationship between migration stress and having sex with risk partners. Moderated mediation model was applied to investigate if social capital can moderate the mediation model (the upper panel of Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual (upper panel) and statistical diagram (lower panel) for the proposed moderated mediation model

We tested the proposed mediation and moderated mediation models (Figure 1) using a specialized method reported by Hayes (Hayes, 2013) with improved efficiency for modeling and validity statistical inferences. As shown in the low panel of Figure 1, the product of the estimated coefficients a1 and b1 (a1*b1) provided a measure of the variable depression in mediating the relationship between migration stress and having sex with risk partners; a significant a3 and b3 provided a measure of the effects of social capital in moderating the impacts of migration stress on depression and depression on having sex with risk partners. An estimated coefficient was considered statistically significant at p<.05 level if the estimated 95% confidence interval did not containing zero. In all the modeling analysis, age, marital status, education and years of migration (continuous) were controlled as covariates. All statistical analyses were conducted using the commercial software SAS, v.9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of the study sample

Among the total sample of 1,135 participants, 50.40% were male, with a mean age of 32.46 (SD=7.89) years. One third (32.68%) of the sample had a high school or more education, 78.36% married and 38.15% with monthly income greater than 2,000 YUAN (RMB, approximately $330). Of the sample, 18.59% migrated to three or more cities, and 52.16% stayed in the current city less than 10 years. Approximately a half reported home visits twice per year or more, and 82.2% reported sending money home. Of the sample, 18.50% reported having intention to move to other cities, 48.19% were residing in the old town, 66.43% lived in rental properties, and 39.21% lived alone. 4.14% have had sex with risk partners (6.29% for males and 1.95% for females).

Correlations among the predictor, mediator, moderator and outcome variables

Results in Table 2 indicate that migration stress was significantly associated with depression. Bonding capital was negatively associated with migration stress and depression only for the total sample. When analyzed by gender, depression was significantly correlated with having sex with risk partners for males, supporting the hypothesized role of depression in bridging the relationship between migration stress and sex with risk partners for males. The correlations between the covariates were also provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlation between social capital, migration stress, depression and having sex with risk partners among rural migrants

| Variables | Mean (SD) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||||||||

| 1. Social capital | 20.68 (4.54) | 0.77** | 0.90** | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.15** | −0.02 | 0.07* |

| 2. Bonding capital | 11.59 (2.21) | 0.41** | −0.08* | −0.06* | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.18** | −0.06* | 0.07* | |

| 3. Bridging capital | 9.10 (3.15) | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.09* | 0.01 | 0.05 | ||

| 4. Migration stress | 2.61 (0.66) | 0.45** | 0.01 | 0.15** | −0.07* | 0.15** | 0.13** | |||

| 5. Depression | 1.99 (0.71) | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 | ||||

| 6. Sex with risk partners | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 | |||||

| 7. Age | −0.27** | 0.58** | 0.63** | |||||||

| 8. Education | −0.30** | −0.20** | ||||||||

| 9. Marital status | 0.37** | |||||||||

| 10. Years of migration | ||||||||||

| Male | ||||||||||

| 1. Social capital | 20.94 (4.66) | 0.79** | 0.91** | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.11* | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| 2. Bonding capital | 11.72 (2.20) | 0.46** | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.13* | −0.05 | 0.02 | |

| 3. Bridging capital | 9.22 (3.23) | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||

| 4. Migration stress | 2.62 (0.70) | 0.43** | 0.03 | 0.18** | −0.04 | 0.19** | 0.17** | |||

| 5. Depression | 1.95 (0.70) | 0.13* | −0.07 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.01 | ||||

| 6. Sex with risk partners | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.02 | −0.09* | 0.03 | 0.03 | |||||

| 7. Age | −0.22** | 0.67** | 0.68** | |||||||

| 8. Education | −0.26** | −0.18** | ||||||||

| 9. Marital status | 0.46** | |||||||||

| 10. Years of migration | ||||||||||

| Female | ||||||||||

| 1. Social capital | 20.43 (4.40) | 0.76** | 0.88** | −0.05 | −0.004 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.19** | −0.02 | 0.11* |

| 2. Bonding capital | 11.45 (2.21) | 0.37** | −0.10 | −0.07 | 0.11* | 0.05 | 0.22** | −0.06 | 0.11* | |

| 3. Bridging capital | 8.97 (3.07) | −0.001 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.11* | 0.01 | 0.08 | ||

| 4. Migration stress | 2.60 (0.62) | 0.49** | −0.03 | 0.12* | −0.10* | 0.11* | 0.07 | |||

| 5. Depression | 2.04 (0.72) | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| 6. Sex with risk partners | 0.02 (0.14) | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | |||||

| 7. Age | −0.33** | 0.46** | 0.57** | |||||||

| 8. Education | −0.34** | −0.22** | ||||||||

| 9. Marital status | 0.28** | |||||||||

| 10. Years of migration |

Note:

p<0.001,

p<0.05

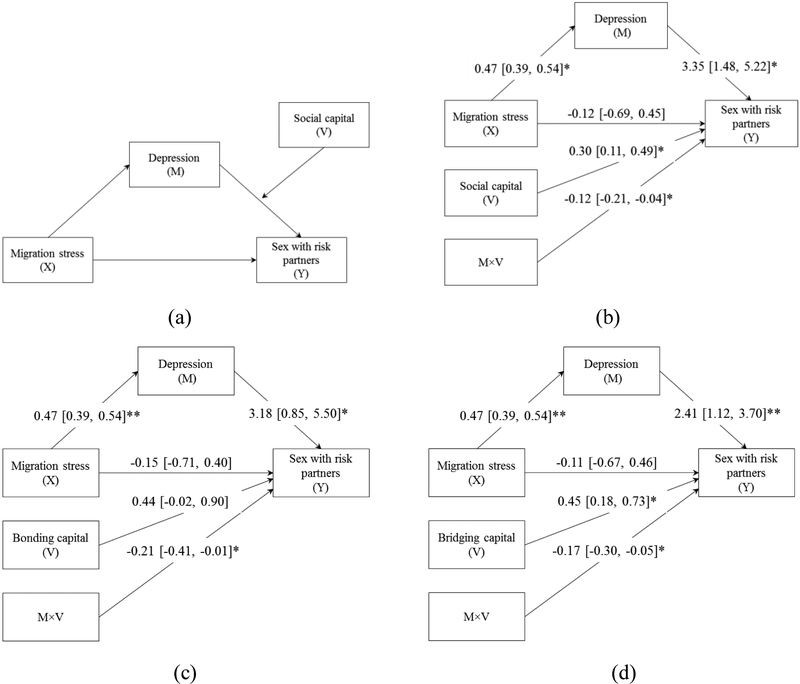

Mediation modeling analysis

Mediation modeling analysis indicated that depression significantly mediated the relationship between migration stress and having sex with risk partners for males with indirect effect [95%CI] = 0.36 [0.08, 0.66] (Figure 2). The mediation effect was not significant for the total sample with indirect effect [95%CI] = 0.21 [−0.06, 0.46]), and the coefficient a (migration stress→depression) 0.51 [0.45, 0.57], the coefficient b (depression→having sex with risk partners) 0.40 [−0.04, 0.84] and the coefficient c’ (migration stress→having sex with risk partners when controlling for depression) −0.12 [−0.62, 0.37]. For the subsample of females, the indirect effect was −0.30 [−0.81, 0.15], and a = 0.58 [0.50, 0.67], b = −0.53 [−1.54, 0.49] and c’ = −0.01 [−1.09, 1.08].

Figure 2. Mediation modeling analysis of the relationship among migration stress, depression and having sex with risk partners (male migrant subsample only, n=572).

Note: (1) Covariates controlled in the modeling analysis were: age, marital status, education and years of migration. (2) The same analysis revealed that depression was not a significant mediator for the total sample and for female subsample (results not shown). (3) *p<0.05, **p<0.01

Moderated mediation analysis

Figure 3 presented results from the moderated mediation analysis. Social capital significantly and negatively moderated the depression-sex with risk partners relationship with M×V effect = −0.12 [−0.21, −0.04] in Figure 3b. Similar moderation effect was observed for bonding capital (Figure 3c: M×V effect =−0.21 [−0.41, −0.01]) and bridging capital (Figure 3d: M×V effect =−0.17 [−0.30, −0.05]).

Figure 3. Moderated mediation modeling analysis of the complex relationship among social capital migration stress, depression and having sex with risk partners, male migrant subsample (n=572): (a) conceptual diagram, (b) total social capital as moderator, (c) bonding capital as moderator and (d) bridging capital as moderator.

Note: (1) Covariates controlled in the modeling analysis were age, marital status, education and years of migration. (2) The same analysis revealed that depression was not a significant mediator for the total sample and for female subsample (results in text). (3) The moderation effect of social capital on the path from migration stress to depression was not significant, thus according to the guidance of moderated mediation model by Hayes, the moderation effect was removed from the final model. (4) *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Discussion

In this study, we verified the role of depression in mediating the association between migration stress and engagement in sexual risk behaviors among male rural-to-urban migrants (Yu et al., 2017), and investigated the effect of social capital in moderating the mediation model. Findings of the study provide useful evidence advancing our understanding of the role of social capital in buffering the complex relationship among migration stress, depression and sexual risk behaviors. Findings of this study warrant further research in other cities and outside of China to assess the generalizability of study findings and studies with longitudinal data to verify if the complex relationships we observed in the study are causal.

Mediation effect of depression and gender difference

Findings of this study suggest that male migrants under stressed are at increased risk of suffering from depression, and depressed migrants are at increased risk to engage in sexual risk behaviors. This relationship suggests that migrants suffering from migration stress and depression may use risk sexual behaviors as a coping strategy (Sudhinaraset, Mmari, Go, & Blum, 2012; T. Yang et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2017). Alternative coping strategies may include but not limited to cigarette smoking, binge drinking, using illicit drugs and even suicide. Our study also found that depression did not mediate the association between migration stress and sexual risk behaviors among female rural migrants. It is possible that female migrants may intend to adopt alternative approaches rather than risky sex to cope with migration stress and depression (Yu et al., 2017). One meta-analysis indicated that women are more likely to use verbal expressions to seek for social support and ruminate about problems, and they have more positive self-talk compared to men (Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, 2002).

Additionally, depression acted not only as a mediator, but it fully mediated the migration stress–risky sex relationship. The finding suggests that migration stress alone may not be sufficient for migrants to seek risk sexual behaviors as coping strategy. However, when strong and long-lasting stress has resulted in depression, a migrant may seek exciting and stimulating behaviors for coping (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005), risk sexual behavior thus would be an option for rural migrants in urban settings. Therefore, interventions on reducing migration stress and depression, as well as decreasing the effects of migration stress on depression and/or depression on risk sex, are strongly needed.

Moderation effect of social capital

One unique finding of this study is the demonstration of the role of social capital in moderating the mediation relationship of migration stress–depression–risky sex. First, social capital showed significant effect in modifying the association between depression and having sex with risk partners. No published studies have examined the role of social capital in moderating the mediation effect of depression that links migration stress to risk sexual behaviors. From our understanding, it’s reasonable that relative to a rural migrants with less social capital, a migrant with more social capital can receive informational, emotional and instrumental support if depressed (Kawachi & Berkman, 2000; Ryan et al., 2008), reducing the likelihood to engaging in risk sexual behaviors.

Second, we also observed that both bonding and bridging capital moderated the mediation model. Bonding capital links individuals together, such as friends and colleagues (Chen, Yu, Gong, Wang, & Elliott, 2017; Whitley & McKenzie, 2005). These people may provide emotional support when migrants suffer from depression, reducing the likelihood of progressing to risk sexual behaviors. Bridging capital links individuals with groups/organizations, such as community health center and local non-profit organizations (NGOs). These groups may occupy rich resources, and provide informational and instrumental support for individuals with depression, such as providing information about psychological counseling, and offering available healthcare for migrants’ families. Thus these migrants may be less likely to use risk sexual behaviors to cope with depression.

Third, from theoretical perspective, social capital may also buffer the impact of stress on depression. However, we did not observe this effect in this study. The lack of moderation effect could due to the difference between migration stress and depression and the research design we used for this study. Relative to depression that can be long-lasting, migration stress is a more volatile process that comes and goes more rapidly. Therefore, the moderation effect of social capital on migration stress-depression relationship could not be effectively detected using cross-sectional data.

Finally, like the mediation effect, the moderation effect of social capital was observed for male migrants only. Reported studies indicated that relative to males, female migrants are more likely to be stressed and depressed (Yu et al., 2017), and this difference was also revealed in this study. It is unclear why there is a lack of moderation effect of social capital on the mediation mechanisms. One possible reason could be due to the small number of female migrants in our sample who reported having had sex with risk partners in the past year. Different from most reported studies on sexual risk behavior, participants in the study is a probability sample representing all female migrants in a city, not those female migrants who were engaging HIV risk behaviors, such as commercial sex workers. Therefore, only 20 female participants reported having had sex with risk partners.

Findings of the study is of great significance for developing more effective interventions against risk sexual behaviors. From the perspective of bonding capital, interventions on family and peer are needed by delivering the message through various approaches, such as social media and health education programs. While interventions for bridging capital, organized groups, such as NGOs, community center, and country fellow organizations, are preferred in the target area with high density of migrants. It will be more effective to conduct interventions through these groups by organized activities. One social capital based community intervention has been proven effective in promoting physical exercise and preventing stroke and heart attack in China (Gong et al., 2015), providing clues for future interventions on risk sexual behaviors through social capital based programs.

Limitations and conclusions

The study has limitations. First, this study is cross-sectional, no causal relationship is warranted. However, data from cross-sectional study are snapshots of a longitudinal process, and providing information regarding the dynamic changes in the variables used in the study (Yu, Chen, & Wang, 2018). Thus, findings from the study still provided useful information regarding the potential mechanism of mental health and sexual risk behaviors. Second, this study targeted rural migrants in one city, cautions are needed when generalizing study findings to other cities within and outside of China. Third, the outcome variable was based on self-report. Given the sensitive nature of sex-related questions, underreport could not be ruled out due to social desirability bias. Despite the limitations, this study is the first to apply a moderated mediation model in investigating the complex underlying mechanisms regarding sexual risk behaviors among rural migrants in China by considering social capital. Findings of this study provide timely and important data informing HIV prevention in China considering the role of social capital.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample

| Variables | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 572 (50.40) | 563 (49.60) | 1135 (100.00) |

| Age (in years) | |||

| Range | 18–45 | 18–45 | 18–45 |

| Mean (SD) | 32.14 (8.16) | 32.79 (7.59) | 32.46 (7.89) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Primary or less | 57 (10.00) | 95 (16.90) | 152 (13.43) |

| Middle school | 304 (53.33) | 306 (54.45) | 610 (53.89) |

| High school | 169 (29.65) | 125 (22.24) | 294 (25.97) |

| College or more | 40 (7.02) | 36 (6.41) | 76 (6.71) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Not married | 159 (27.89) | 86 (15.30) | 245 (21.64) |

| Married | 411 (72.11) | 476 (84.70) | 887 (78.36) |

| Income (RMB), n (%) | |||

| 1000 or less | 61 (10.66) | 165 (29.31) | 226 (19.91) |

| 1001–2000 | 220 (38.46) | 256 (45.47) | 476 (41.94) |

| 2001–4000 | 230 (40.21) | 123 (21.85) | 353 (31.10) |

| More than 4000 | 61 (10.66) | 19 (3.37) | 80 (7.05) |

| No. of cities migrated, n (%) | |||

| ≤ 2 cities | 413 (72.20) | 511 (90.76) | 924 (81.41) |

| > 2 cities | 159 (27.80) | 52 (9.24) | 211 (18.59) |

| Year of migration, n (%) | |||

| < 5 years | 185 (32.34) | 175 (31.08) | 360 (31.72) |

| 5–10 years | 101 (17.66) | 127 (22.56) | 228 (20.09) |

| 10–15 years | 119 (20.80) | 128 (22.74) | 247 (21.76) |

| ≥ 15 years | 167 (29.20) | 133 (23.62) | 300 (26.43) |

| Mean (SD) | 10.44 (7.56) | 9.89 (7.03) | 10.17 (7.30) |

| Times of visiting home per year, n (%) | |||

| ≤ 2 times | 294 (51.40) | 325 (27.73) | 619 (54.54) |

| > 2 times | 278 (48.60) | 238 (42.27) | 516 (45.46) |

| If send money home, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 479 (83.74) | 454 (80.64) | 933 (82.20) |

| Intention of moving to other cities, n (%) | |||

| Likely | 144 (25.17) | 66 (11.72) | 210 (18.50) |

| Unsure | 103 (18.01) | 91 (16.16) | 194 (17.09) |

| Unlikely | 325 (56.82) | 406 (72.11) | 731 (64.41) |

| Residential locations, n (%) | |||

| Old town | 274 (47.90) | 273 (48.49) | 547 (48.19) |

| New town | 112 (19.58) | 107 (19.01) | 219 (19.30) |

| Urban-rural fringe zone | 105 (18.36) | 95 (47.50) | 200 (17.62) |

| Suburban | 81 (14.16) | 88 (15.63) | 169 (14.89) |

| If rent house, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 370 (64.69) | 384 (68.21) | 754 (66.43) |

| If living alone, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 250 (43.71) | 195 (34.64) | 445 (39.21) |

| If sex with risk partners, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 36 (6.29) | 11 (1.95) | 47 (4.14) |

| Condom use if sex with risk partners, n (%) | |||

| Never | 18 (50.00) | 6 (54.55) | 24 (51.06) |

| Occasional | 4 (11.11) | 3 (27.27) | 7 (14.89) |

| Often | 4 (11.11) | 0 (0) | 4 (8.51) |

| Always | 10 (27.78) | 2 (18.18) | 12 (25.53) |

Acknowledgements

We thank other researchers and community health workers who participated in the data collection and processing. The work would not be possible without their efforts.

Source of Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health at National Institute of Health under Grant [R01 MH08632, PI: XC].

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Reference

- Almedom AM (2005). Social capital and mental health: an interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Social Science &Medicine, 61(5), 943–964. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhanian YA, Kuznetsova AV, Kelly JA, DiFranceisco WJ, Musatov VB, Avsukevich NA, … McAuliffe TL (2011). Male Labor Migrants in Russia: HIV Risk Behavior Levels, Contextual Factors, and Prevention Needs. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13(5), 919–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archuleta AJ, & Miller CR (2011). Validity evidence for the translated version of the Personal Social Capital Scale among people of Mexican Descent. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 2(2), 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Berry J (1997). Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 5–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J (2006). Acculturative stress. In Wong P & Wong L (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping (pp. 283–294). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D (2004). Migration and mental health. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109(4), 243–258. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690X.2003.00246.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Breslau J, & Aguilar-Gaxiola S (2007). The effect of migration to the United States on substance use disorders among returned Mexican migrants and families of migrants. American Journal of Public Health, 97(10), 1847–1851. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer CB, Greenberg L, Chutuape K, Walker B, Monte D, Kirk J, … Adolescent Medicine Trials Network. (2017). Exchange of Sex for Drugs or Money in Adolescents and Young Adults: An Examination of Sociodemographic Factors, HIV-Related Risk, and Community Context. Journal of Community Health, 42(1), 90–100. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0234-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Hu H, Xu X, Gong J, Yan Y, & Li F (2018). Probability Sampling by Connecting Space with Households using GIS/GPS Technologies. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, 6(2), 149–168. doi: 10.1093/jssam/smx032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Stanton B, Gong J, Fang X, & Li X (2009). Personal Social Capital Scale: an instrument for health and behavioral research. Health Education Research, 24(2), 306–317. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Stanton B, Kaljee LM, Fang X, Xiong Q, Lin D, … Li X (2011). Social Stigma, Social Capital Reconstruction, and Rural Migrants in Urban China: A Population Health Perspective. Human Organization, 70(1), 22–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang P, Wegner R, Gong J, Fang X, & Kaljee L (2015). Measuring social capital investment: scale development and examination of links to social capital and perceived stress. Social Indicators Research, 120(3), 669–687. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0611-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yu B, Gong J, Wang P, & Elliott AL (2017). Social Capital Associated with Quality of Life Mediated by Employment Experiences: Evidence from a Random Sample of Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China. Social Indicators Research, 139(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s11205-017-1617-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yu B, Gong J, Zeng J, & MacDonell K (2015). The domestic migration stress questionnaire (DMSQ): development and psychometric assessment. Journal of Social Science Studies, 2(2), 117. doi: 10.5296/jsss.v2i2.7010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yu B, Zhou D, Zhou W, Gong J, Li S, & Stanton B (2015). A Comparison of the Number of Men Who Have Sex with Men among Rural-To-Urban Migrants with Non-Migrant Rural and Urban Residents in Wuhan, China: A GIS/GPS-Assisted Random Sample Survey Study. Plos One, 10(8), e0134712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WG (1977). Sampling techniques (3d ed., p. xvi, 428 p.). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, Holtgrave DR, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, & Gayle JA (2003). Social capital as a predictor of adolescents’ sexual risk behavior: a state-level exploratory study. AIDS and Behavior, 7(3), 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W, Gao J, Gong J, Xia X, Yang H, Shen Y, … Pan Z (2015). Sexual behavior of migrant workers in Shanghai, China. BMC Public Health, 15, 1067. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2385-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Melisaratos N (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700048017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KM, Piko BF, Wright DR, & LaGory M (2005). Depressive symptomatology, exposure to violence, and the role of social capital among African American adolescents. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(2), 262–274. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M (2004). Migrant Resettlement in the Russian Federation: Reconstructing’homes’ and’homelands. Anthem Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, & Kawachi I (2008). A prospective study of individual-level social capital and major depression in the United States. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(7), 627–633. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.064261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannou FK, Tsiara CG, Nikolopoulos GK, Talias M, Benetou V, Kantzanou M, … Hatzakis A (2016). Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on HIV serodiscordant couples. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 16(4), 489–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J, Chen X, & Li S (2015). Efficacy of a Community-Based Physical Activity Program KM2H2 for Stroke and Heart Attack Prevention among Senior Hypertensive Patients: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Phase-II Trial. Plos One, 10(10), e0139442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove RM (2004). Survey Methodology. New York: Wiley-Interscience, A John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Harpham T, Grant E, & Rodriguez C (2004). Mental health and social capital in Cali, Colombia. Social Science & Medicine, 58(11), 2267–2277. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD, & Magaña C (2000). Acculturative stress, anxiety, and depression among Mexican immigrant farmworkers in the midwest United States. Journal of Immigrant Health, 2(3), 119–131. doi: 10.1023/A:1009556802759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, & Berkman L (2000). Social cohesion, social capital, and health. Social Epidemiology, 174–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, & Kim D (2008). Social capital and health In Ichiro Kawachi, Subramanian SV, & Kim D (Eds.), Social capital and health (pp. 1–26). New York, NY: Springer New York. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-71311-3_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Bahr GR, Koob JJ, Morgan MG, Kalichman SC, … St. Lawrence JS. (1993). Factors associated with severity of depression and high-risk sexual behavior among persons diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Health Psychology, 12(3), 215–219. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.3.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS (2006). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Wang H, Ye X, Jiang M, Lou Q, & Hesketh T (2007). The mental health status of Chinese rural-urban migrant workers : comparison with permanent urban and rural dwellers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(9), 716–722. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0221-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Chen X, Li S, Yu B, Wang Y, & Yan H (2016). Path Analysis of Acculturative Stress Components and Their Relationship with Depression Among International Students in China. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 32(5), 524–532. doi: 10.1002/smi.2658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundborg P (2005). Social capital and substance use among Swedish adolescents--an explorative study. Social Science & Medicine, 61(6), 1151–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of the PRC. (2016). 2015 Surveillance report of rural-to-urban migrants. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201604/t20160428_1349713.html

- Ottesen L, Jeppesen RS, & Krustrup BR (2010). The development of social capital through football and running: studying an intervention program for inactive women. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 20 Suppl 1, 118–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD (2000). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Culture and Politics, 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Requena F (2003). Social capital, satisfaction and quality of life in the workplace. Social Indicators Research, 61(3), 331–360. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SH, Halstead JM, Gardner KH, & Carlson CH (2011). Examining Walkability and Social Capital as Indicators of Quality of Life at the Municipal and Neighborhood Scales. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 6(2), 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan L, Sales R, Tilki M, & Siara B (2008). Social networks, social support and social capital: The experiences of recent Polish migrants in London. Sociology, 42(4), 672–690. [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR, Ryce P, Gupta T, & Rogers-Sirin L (2013). The role of acculturative stress on mental health symptoms for immigrant adolescents: a longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 736–748. doi: 10.1037/a0028398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrabski A, Kopp M, & Kawachi I (2004). Social capital and collective efficacy in Hungary: cross sectional associations with middle aged female and male mortality rates. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58(4), 340–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N, & Kawachi I (2014). State-level social capital and suicide mortality in the 50 U.S. states. Social Science & Medicine, 120, 269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman D, & Gray R (1991). Cost-efficient study designs for binary response data with Gaussian covariate measurement error. Biometrics, 47(3), 851–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Bureau of Wuhan. (2015). Wuhan Statistical Yearbook-2015. Beijing: China Statistics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhinaraset M, Mmari K, Go V, & Blum RW (2012). Sexual attitudes, behaviours and acculturation among young migrants in Shanghai. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14(9), 1081–1094. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.715673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamres LK, Janicki D, & Helgeson VS (2002). Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review : An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 6(1), 2–30. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant C (2002). Life events, stress and depression: a review of recent findings. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(2), 173–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilly C (2007). Trust networks in transnational migration. Sociological Forum, 22(1), 3–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1573-7861.2006.00002.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiruneh K, Wasie B, & Gonzalez H (2015). Sexual behavior and vulnerability to HIV infection among seasonal migrant laborers in Metema district, northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 15, 122. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1468-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás-Sábado J, Qureshi A, Antonin M, & Collazos F (2007). Construction and preliminary validation of the Barcelona Immigration Stress Scale. Psychological Reports, 100(3 Pt 1), 1013–1023. doi: 10.2466/pr0.100.3.1013-1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Chen X, Gong J, & Jacques-Tiura AJ (2013). Reliability and validity of the personal social capital scale 16 and personal social capital scale 8: Two short instruments for survey studies. Social Indicators Research, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford H, Cullen M, & Baingana F (2005). Social capital and mental health. Promoting Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley R, & McKenzie K (2005). Social capital and psychiatry: review of the literature. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 13(2), 71–84. doi: 10.1080/10673220590956474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CT, & Latkin CA (2005). The role of depressive symptoms in predicting sex with multiple and high-risk partners. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 38(1), 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank World. (2017). Migration overview. Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/migrationremittancesdiasporaissues/overview

- Yang H, Li X, Stanton B, Chen X, Liu H, Fang X, … Mao R (2005). HIV-related risk factors associated with commercial sex among female migrants in China. Health Care for Women International, 26(2), 134–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Wang W, Abdullah AS, Beard J, Cao C, & Shen M (2009). HIV/AIDS-related sexual risk behaviors in male rural-to-urban migrants in China. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 37(3), 419–432. [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Chen X, & Li S (2014). Globalization, cross-cultural stress and health. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 35(3), 338–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Chen X, & Wang Y (2018). Dynamic transitions between marijuana use and cigarette smoking among US adolescents and emerging adults. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(4), 1–11. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2018.1434535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Chen X, Yan Y, Gong J, Li F, & Roberson E (2017). Migration Stress, Poor Mental Health, and Engagement in Sex with High-Risk Partners: A Mediation Modeling Analysis of Data from Rural-to-Urban Migrants in China. Sexuality Research & Social Policy : Journal of NSRC : SR & SP, 14(4), 467–477. doi: 10.1007/s13178-016-0252-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]